#rob sheffield

Text

insane behaviour

500 notes

·

View notes

Note

I dont think I've ever heard the take that girl seems to be about Paul, I mean, it makes sense absolutely, but can you expand some more?

Gladly, Anon.

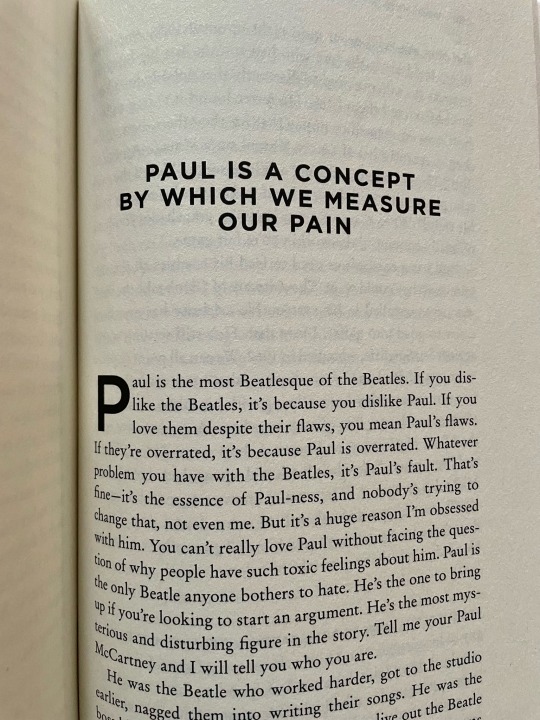

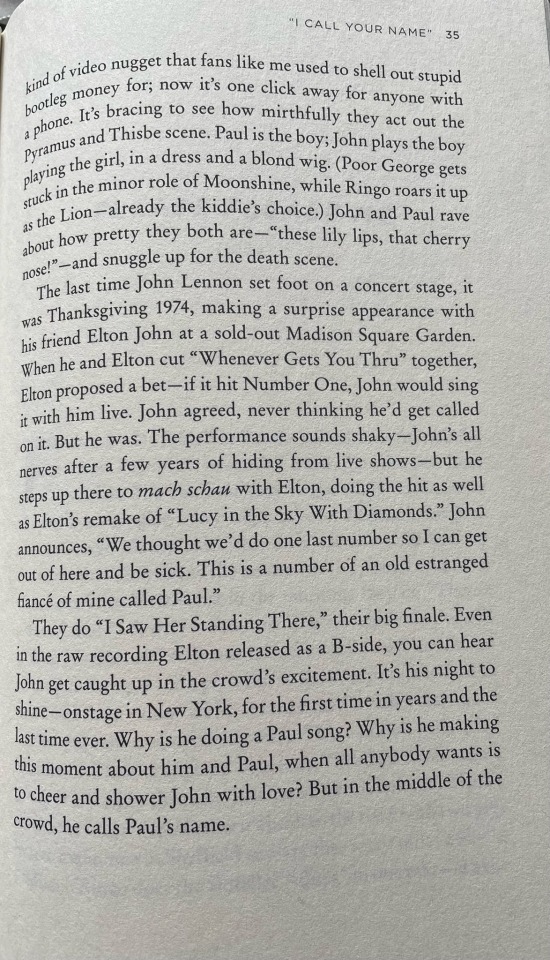

Rob Sheffield (Dreaming the Beatles) said he thinks Girl is about Paul in this episode of @anotherkindofmindpod. The episode is actually an in-depth discussion of In My Life, but Girl came up a number of times, since it's also on Rubber Soul.

I thought Sheffield's statement was interesting, and not in a silly “John saw Paul as a girl” kind of way.

Summarizing mercilessly, and taking a few steps back before returning to Girl:

RS argues that Rubber Soul marks a moment when the Beatles’ songwriting moved from a commercial/craft perspective towards a more open/confessional/personal tone, In My Life being an example of this, with John examining his feelings for all his friends and lovers, and singling out a new kind of love that transcends the loves he’s known before. According to RS and the hosts, In My Life is not only addressed to Paul (I personally feel it could also be about Julian, or about both; as someone who writes, I really feel the “a piece of art is never about just one thing” argument)— it also, by summoning a group of dear people and openly expressing his feelings for them, emulates Paul, who, in John’s eyes, is the more extrovert and socially comfortable of the two. The song is a two-fold tribute.

Girl, still according to RS, forms a matched pair with In My Life, because it, too, concerns complex and intimate emotions; in this case being unsettled by a complex, alluring and confusing person (Paul/the girl). It's a non-generic, specific, highly personal song you wouldn't have found on earlier albums. (You Won’t See Me is Paul’s reply to John.)

Whether you agree with these interpretations or not (by the way, instead of trusting my summary, it’s probably a better idea to listen to RS and the hosts in their own words), I’m happy to see the acknowledgment of the depth of John and Paul's relationship.

RS also makes a beautiful point about If I Fell (which, as we know, John saw as a continuation of In My Life): That John and Paul, as always, tell the truth about each other by the way they sing together.

(Cue the If I Fell/marriage vows quote from Gould’s Beatles bio).

Ian Leslie (no introduction needed) was more direct in his “Hidden Gems” episode on @onesweetdreampodcast. He stated he believes that If I Fell was written for Paul, commemorating their Paris ‘honeymoon’.

And look—people are free to go as far as they want in how they interpret all this, but I personally feel it liberates and elevates the discussion of their songwriting and relationships to include the romantic love or friendship or X or [redacted] or 'tender and tempestuous' but ‘not sexual as far as we know’ relationship between John and Paul as one of its many possible inspirations.

It just feels silly to me to ignore it or act all offended at the mere suggestion.

And when RS writes in Dreaming the Beatles “For John, Paul was the boy who came to stay; for Paul, John was the song he couldn’t make better,” it just feels right.

My two cents.

P.S. When I'm inclined to accept that Girl is about Paul, I immediately want to ask follow-up questions. Because this is a song about a fraught relationship, right? In what sense did John try to leave Paul? In what sense did Paul promise him the earth and cry? I know it doesn't have to be literally true, but some extrapolation, please? This didn't happen in the episode—obviously, since its focus was another song, In My Life.

PPS: I wrote this in a bit of a hurry so feel free to get back to me for clarifications, etc.

#rob sheffield#dreaming the beatles#girl#rubber soul#the beatles#john lennon#paul mccartney#if i fell#in my life#AKOM#mclennon#asks#one sweet dream podcast

98 notes

·

View notes

Text

on earth we’re briefly gorgeous by ocean vuong // love is a mixtape by rob sheffield // 20th century women (2016) // a world alone - lorde // quote by anna akhmatova // quote by friedrich nietzsche // i carry your heart with me by E.E. cummings // level 5 (1997) // wait by galway kinnell // chiquitita - abba

#on music#quotes#comparisons#parallels#compilation#poetry#poetry compilation#web weave#web weaving#webweaving#book quotes#rob sheffield#ocean vuong#movie quotes#lorde#lyrics

776 notes

·

View notes

Text

Article text: BEYONCÉ HAS SO many audacious culture-clash triumphs all over Cowboy Carter. But one of the most stunning moments is also one of the simplest: her version of the Beatles classic “Blackbird.” Paul McCartney wrote the song in the summer of 1968, inspired by the American civil rights movement. All that history is right there in Beyoncé’s version. She keeps the folkie Paul guitar, complete with the squeaks, but adds her heavenly gospel-soul harmonies. What she does with the word “arise” is incredible in itself.

It’s a stroke of Beyoncé’s revisionary genius that brings the story of “Blackbird” full circle. She claims the song as if Paul McCartney wrote it for her. Because, in so many ways, he did.

Paul tells the story of writing it in his 2021 book The Lyrics. “At the time in 1968 when I was writing ‘Blackbird,’” he recalls, “I was very conscious of the terrible racial tensions in the U.S. The year before, 1967, had been a particularly bad year, but 1968 was even worse. The song was written only a few weeks after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. That imagery of the broken wings and the sunken eyes and the general longing for freedom is very much of its moment.”

Paul wrote this song as a dialogue with Black America; Bey’s “Blackbird” is part of that call-and-response, proof that the song always meant exactly what McCartney hoped it would mean. It’s one of the most profound and powerful Beatles covers ever, right up there with Aretha Franklin’s “The Long and Winding Road.”

“I had in mind a Black woman, rather than a bird,” Paul says of the song in the 1997 book Many Years From Now, by Barry Miles. “Those were the days of the civil rights movement, which all of us cared passionately about, so this was really a song from me to a Black woman, experiencing these problems in the States: ‘Let me encourage you to keep trying, to keep your faith, there is hope.’”

#beyonce#paul mccartney#rob sheffield#I love this cover#the American Requiem to Blackbird to 16 Carriages sequence is so good!#I also love Daughter#and My Rose and Bodyguard and Alligator Tears#and I’m not even done yet!

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

Media: Cassettes

Tonight, I feel like my whole body is made out of memories. I'm a mix-tape, a cassette that's been rewound so many times you can hear the fingerprints smudged on the tape.

#mix tape#Vintage#Tapes#cassette tapes#cassette#cassettes#Tape cassette#casette#casette tapes#Mix tapes#Media#Old media#vintage media#Recording tapes#moodboard#aesthetic#Media aesthetic#Music#Objects#Object aesthetic#Object moodboard#physical media#music aesthetic#music moodboard#rob sheffield

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

rob sheffield really out here saying this stuff and retweeting taylor profile pics quoting it back to him with paris 1961 pics.

actually literally me

89 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rob Sheffield:

(The final scene of Jackson’s video will wipe you out for real — be prepared when you watch.)

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm not crying, you're crying.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

"WHAT IS GOING on here? Why are idiot fans throwing stuff during live shows? It’s reached a crisis point in the past couple weeks—a disturbing and loathsome epidemic of fan aggression against performers. On Wednesday, Kelsea Ballerini got hit in the face when a concertgoer threw a bracelet at her—just the latest case of a female artist assaulted in the middle of a show. Why is this happening, and how do we stop it?

Ballerini was in Boise, Idaho, doing her country-pop hit “If You Go Down (I’m Goin’ Too),” when the bracelet came out of nowhere and hit her face, right near her left eye. She left the stage, but then returned to finish her show. “Can we talk about what just happened?” she said, in admirably clear terms. “Don’t throw things, you know? I just always want shows of mine—every show, for every artist—but I’m in control of this one. I just want it to be a safe place for everyone. Can you help me do that tonight?”

It’s not an isolated case. Bebe Rexha needed three stitches after she got hit by a thrown iPhone at a NYC rooftop show on June 18, and posted a photo of her frighteningly bruised and bandaged face. The alleged assailant, a 27-year-old man, told police, “I was trying to see if I could hit her with the phone at the end of the show because it would be funny.” He also helpfully explained, “It’s a TikTok trend.” Oh.

Two days later, Ava Max was assaulted by a man who crashed the stage at an L.A. show and slapped her in the face. She posted, “He slapped me so hard that he scratched the inside of my eye.” A couple days later, in London’s Hyde Park, Pink got interrupted mid-song by someone throwing a bag of their dead mother’s ashes. A true pro, Pink asked, “Is this your mom?” Then she put down the bag and said, “I don’t know how I feel about this.”

It can’t be overstated how much this sucks. Miley Cyrus recently declared she doesn’t feel safe doing arena shows anymore. As she explained, “There’s no connection. There’s no safety.”

Ballerini posted an update to her Instagram Story on Thursday, saying, “hi. i’m fine. someone threw a bracelet, it hit me in the eye, and it more so just scared me than hurt me. we all have triggers and layers of fears way deeper than what is shown, and that’s why i walked offstage to calm down and make sure myself, band and crew, and the crowd all felt safe.”

How did we get here? These are important artists with things to say and music to make. It’s not their job to explain why idiots shouldn’t throw things at them onstage. But it’s simpler than that—they’re human beings. What these incidents have in common is a bizarre lack of respect, a main-character neediness for attention, a child’s ignorance of boundaries. This isn’t fan enthusiasm going overboard—this is hostility disguised as fandom.

So: it’s weird that this needs to be said, but don’t throw things at the artist, mmmmkay? No matter how soft and fluffy it seems. A cute li’l stuffed animal turns into a weapon if it hits somebody, as happened to Lady Gaga in Toronto last fall. A bracelet can do serious damage. Somebody threw a lollipop at David Bowie in 2004, in Norway, and almost blinded him. A lollipop. Nobody wants concerts to turn into airport-security hellholes with body-cavity searches. Your elderly loved ones do not need the aggravation of amending their wills to say, “BTW, after I die, if it ever seems like a cool idea to bombard a hard-working music legend with the remains of my incinerated corpse, switch to decaf and think again.”

Why now? So much of it comes down to the pandemic. People got out of practice at going to shows, so they forgot how to be audiences. Or else they just started their concertgoing years now, without having learned from being part of an experienced audience. But in 18 months of isolation, the whole fan culture around live music shut down—the traditions, the habits, the manners, the codes of honor, the spirit of “act like you’ve been there before.” It was a disastrous loss for music and the community around it. When live music returned, some fans were desperate to get back into the action, but without remembering the details of how to handle themselves in an IRL crowd. That’s how you get a grown adult boasting he threw a piece of metal at a celebrity to join a “TikTok trend.”

But this wave of fan aggression evokes those horror stories from the Seventies, like the notorious 1971 incident when a London concertgoer pushed Frank Zappa off the stage, putting him in a wheelchair and nearly breaking his neck. Or when “some stupid with a flare gun” burned down the Montreux Casino, inspiring Deep Purple to write “Smoke on the Water.” (Respect to the late great Funky Claude, who ran back into the burning building to pull kids out.) Over time, audiences gradually learned how to be cool in a concert crowd, until the coronvirus. So there’s a lot of Some Stupid going around.

There’s always been a certain etiquette for live music. It’s taken a beating in the social-media age, as more people treat the live show as a backdrop to stage click-chasing viral stunts.

But it’s unquestionably gotten worse post-pandemic. Last summer, Kid Cudi walked out on the Rolling Loud festival in Miami. “I will fucking leave,” he warned the crowd. “If I get hit with one more fucking thing—if I see one more fucking thing on this fucking stage, I’m leaving. Don’t fuck with me.” Someone then hit him with a water bottle—and bragged about it on Twitter, because of course he did.

Tyler the Creator issued a public plea last year for concertgoers to stop throwing things. “I don’t understand the logic of throwing your shit up here,” Tyler ranted mid-show. “Not only for safety reasons, but bro, I don’t want your shit. I don’t want it. Like, I’m not even being funny. Every show someone throws something up here, and I don’t understand the logic. Why do you think I want your shit? Then if I slip and break my foot? Stop throwing that fucking shit up here, bro!” He went on to say, “Fucking dick-fuck.”

But that message was evidently too subtle for some folks. Steve Lacy stopped a New Orleans show in October when somebody hit him in the leg with a camera. Lacy said, “Don’t throw shit on my fucking stage,” then smashed the camera and left. Rosalia got hit in the face with a bouquet of roses, in San Diego. “Please don’t throw things on the stage,” she tweeted (in Spanish). “And if you’re such motomamis that you throw them anyway, throw them on the opposite side from where I am.” Harry Styles, whose live vibe is the essence of generosity and openness, has gotten his boundaries invaded by Skittles-tossers and chicken-nugget-hurlers. Nobody could blame him for being less than okay with it.

There’s always been a tradition of acts who encourage fans to throw their bras, panties, or flowers. That’s just consensual show-biz. A Tom Jones concert wasn’t complete without tipsy ladies pelting him with their hotel room keys. When a fan threw a bat onstage, Ozzy Osbourne assumed it was a rubber toy, so he playfully took a bite—then became the first rock star ever rushed to the ER for rabies shots after a dose of batflesh. Punk rockers often thrived on the dust-ups. At the Sex Pistols’ famous final gig, Greil Marcus reported that the band got hit with “ice, cups, shoes, coins, pins and probably rocks.” Johnny Rotten complained, “There’s not enough presents. You’ll have to throw up better things that.” Immediately, someone threw a rolled-up umbrella. Johnny replied, “That’ll do.”

But during the pandemic, for many fans, their primary source of human contact was social media, where there is no perk for non-asshole behavior and nothing but rewards for finding novel ways to be a dick. There are so many incentives to create a viral moment, so it seems acceptable to interrupt a show to make strangers notice you. Throwing your phone at something to get its attention—you wouldn’t do that to a squirrel, much less a human, so why would anyone do it to an artist they’ve paid money to see? But social-media culture breeds a new kind of fan mentality defined by parasocial resentment, where fandoms feel so possessive about their faves, they get outraged when their fave doesn’t live up to their demands. It takes a toll on simple human empathy. Our whole culture picked up so many toxic habits it will take years to unlearn.

It doesn’t have to be this way. Almost exactly two years ago, I saw a symbolic return for live music when Madison Square Garden reopened with a super-emotional Foo Fighters show. It felt like all of us in the room were figuring out from scratch how to be fans again. I described it at the time as an “invitation to start remembering how to celebrate together.” Needless to say, the return of live music turned out to be a lot messier than that—lots of stops and starts, lots of conflict and controversy, lots of fear and grief and anger.

But this is the first summer when it’s felt like live shows are really back. My music summer began a month ago with Taylor Swift on her Eras Tour. I saw The Cure and Dead & Company on back-to-back nights, two tribal gatherings that felt like the most uplifting kind of communal devotion. In the past couple weeks, I’ve seen loads of brilliant punk rock (Protomartyr, Wednesday, the Dolly Spartans, the So So Glos, Bar Italia), comeback gigs from old-school heroes (The Feelies, Love and Rockets), and a Beatles tribute band, the Fab Faux (damn fine “Martha My Dear”). It’s time travel, hitting so many different eras of my life as a music fan—past, present, and future. I’ve been trading stories with friends having similar epiphanies this month at Joni Mitchell or DJ Premier or LCD Soundsystem. We were all hungrier for this than we even realized.

The mass rapture of the live show—it’s a fragile temporary community that comes together for a night. Whether it’s in a sleazy bar or a basement or a stadium, it’s a place we go so we can experience those raptures in the dark with strangers, to be part of a story that doesn’t happen when we’re listening by ourselves. But those moments don’t happen without a certain level of mutual trust and respect. And they can’t even begin when the performer can’t trust the audience. We’re all in the crowd for the same reason—to create that space where this rapture can happen. But it’s not something the artists or the industry can conjure up on our behalf. It’s on us to be an audience that the performer can believe in. That’s really where the music begins."

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Our lives were just beginning, our favorite moment was right now, our favorite songs were unwritten.

Love Is a Mix Tape: Life and Loss, One Song at a Time by Rob Sheffield

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

for @frodolives

Dreaming the Beatles: The Love Story of One Band and the Whole World, Rob Sheffield (2017)

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

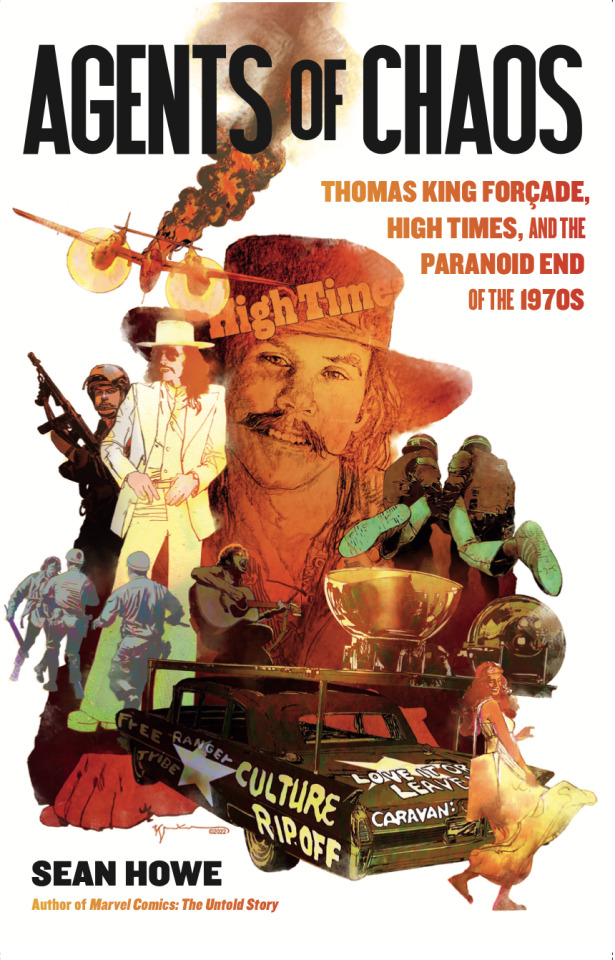

“Who was Tom Forçade? A revolutionary guru? A hippie con man? An undercover cop? In Sean Howe’s brilliant book, he’s a weird one-man secret history of seventies America, a mystery man who keeps showing up everywhere from the early underground press to the punk-rock explosion. Agents of Chaos turns this bizarre tale into an obsessively fascinating and addictive epic, like a countercultural thriller.” —Rob Sheffield (Dreaming the Beatles)

“A fascinating, anecdote-packed tale of drugs, guns, and magazine publishing.” —Entertainment Weekly

“Rollicking history ... captures the freewheeling spirit of the counterculture’s troubled march through the 1970s.” —Publishers Weekly

“A cautionary tale from the countercultural past, full of revolutionary glory and ugly criminality.” —Kirkus Reviews

“Like an obsessed detective hunting a man without a face, Sean Howe has turned the life of Tom Forçade into a detailed metaphor explaining why the seventies were sublime, why the seventies failed, and how those two things are inextricably connected.” —Chuck Klosterman (The Nineties)

“Richly drawn, deadly serious, utterly comical, this book gave me a contact high.” —Joe Hagan (Sticky Fingers: The Life and Times of Jann Wenner and Rolling Stone Magazine)

“A gob-smacking roller coaster ride.” —Tom O'Neill (Chaos: Charles Manson, the CIA, and the Secret History of the Sixties)

Read an excerpt at Rolling Stone here.

#books#book covers#high times#cannabis#radical#journalism#politics#true crime#chuck klosterman#rob sheffield#joe hagan#tom o'neill#charles manson#1970s#drugs#bill sienkiewicz

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

“NEW YORK, ARE you feeling well and emotionally stable?” Harry Styles asked on the opening weekend of his historic 15-night stand at Madison Square Garden. When the entire crowd roared, “Noooo!,” he replied, “Good!” We can’t say he didn’t warn us. He kicked off his NYC Love on Tour residency with a riotous two-night celebration of mega-pop rapture at its most ecstatic. “Please feel free to do whatever you want to do in this room tonight,” Harry told the fans on Night Two. “Within reason.” It was a perfect intro, because the concept of “within reason” does not exist anywhere in the Harry cosmology — he couldn’t even say it with a straight face. Let’s just say this man is not doing wonders for the city’s emotional stability right now.

Styles is trying a new mode of touring, celebrating his blockbuster Harry’s House with extended residencies in New York, Austin, Chicago, and L.A. As he told Rolling Stone’s Brittany Spanos in our brand new cover story, it’s a way to perform without the energy-sucking strains of travel. You can tell Harry’s in town, by the trail of feathers and sequins for blocks — a touch of glam in the dog days of summer. NYC in August is usually a place people are desperate to escape, but he makes it seem like the most romantic destination on the planet.

95 notes

·

View notes

Note

it’s actually from the rolling stone interview in 2019! rob sheffield said that harry put on peace piece when they were driving and it is his morning alarm sound. harry then put a different version of it to his tour intro, the one that had birds singing in the background!

I knew it sounded familiar!!

On the drive over, he puts on the jazz pianist Bill Evans — “Peace Piece,” from 1959, which is the wake-up tone on his phone.

x

41 notes

·

View notes

Link

BY ROB SHEFFIELD | NOVEMBER 11, 2022

LOUIS TOMLINSON IS ready to find his voice as a solo star. His second solo album, Faith in the Future, comes 7 years after the end of One Direction. When he released his excellent solo debut Walls in 2020, he was admirably open about the difficulty of making an album on his own. “It took me a second to get here,” Louis told Rolling Stone. “Because there was a lot of treading water.” But this time feels different for him. As he says now, “I’m just in a more confident place.”

Faith In The Future sounds very distinct from Walls, which was focused on his Oasis-style rock songwriting. It revives the dance sound that he was exploring on his earliest solo singles, when he did collaborations with Steve Aoki and Bebe Rexha. Yet it also has pop ballads like “Chicago” and the Northern English hometown tribute “Common People.” (No relation to the classic Pulp song.) Louis took a break to speak to Rolling Stone about the new album, his love of touring, the confidence he gets from his fans, and his “break free” from One Direction.

Did you feel like you had a lot to prove with this record?

Yeah, man—I had a lot to prove to meself. And a lot to prove to anyone else who’s listening. But I just wanted to be braver with this record. I think there was times on the first album where I kind of dipped my toe into being brave and doing exactly what I wanted to do. But this time I just wanted to embrace what I love musically. There’s a different kind of love for every song. It’s not all trying to be a single.

You explore the different sides of your music in this one.

I wanted it to be broad. I was so paranoid about coming across credible on the first record. So there was an element of me being musically closed-minded. It was important for me, on this record, to be broader than that. I started out my solo career with a dance-pop hybrid thing with Steve Aoki. So for the first album, I didn’t want to go anywhere near as kind of dance-y sounds. I suppose on this record, I’m just in a more confident place, so I’m willing to be braver and do things like that. Or at least what feels braver to me.

You bring back the elements of dance from earlier in your solo career. How did you combine them with the rock guitar of Walls?

I often cite the DMA’s album that they did with Stuart Price. That’s a dance record, but there’s still loads of guitars running through the middle of it. So it gave me good inspiration for this album.

The title Faith in the Future—what does that mean to you?

I suppose it’s a bit of personal reflection. I’ve always had to have “Faith in the Future” in my life, in my career. The first record, it felt really emotional. Not that this record doesn’t, but I want to feel hopeful more than anything. So I wanted to honor it with a really hopeful title.

When we talked for Walls, you said it took you a long time to make that first solo album. Why did this one feel more confident?

I was hoping I’d have a full tour completed when I was going to write this record. Obviously, because of Covid, that didn’t happen. But I was lucky enough to have the two live shows I had before Covid got in the way. That was fresh in me mind when I was writing this whole record. And that gave me a lot of confidence. I think that really had a hand in the album feeling more confident as well.

You’ve got rock energy on this album, like “Out of My System.”

Yeah man, it feels like a throwback when I listen to it. I absolutely love that song, man. That’s a song I’m excited about playing live. I really like the video. I’ve been wanting to do a song like that for a while—it’s cool, isn’t it?

Did performing live have an impact on your songwriting for this album?

Massively. It’s my favorite thing to do. I’m lucky enough to have a lot of success touring as well. So I wanted to focus this album around those shows, and create as many exciting live moments as I could, because as a music fan, that’s the times I remember. I love listening to albums—of course I do. But the times that stay in your memory are the live moments.

Youv’ve always been the kind of live performer who makes that direct connection with the audience.

I can’t take full credit for that, because I think it’s about the connection from the fans as well. Definitely. I feel that from them at every show. And I think that’s what makes us feel connected in that moment.

How did it affect your songwriting to be heading into your thirties?

I suppose you never really know, but I like to think there’s maybe a bit more depth, because you think a little deeper as you get older. Maybe the concepts are more mature. But I don’t really feel like a 30-year-old, to be honest with you.

But you’re an artist who’s still evolving and growing, after you’ve been doing this so long.

That’s why I feel incredibly lucky, man. I had all my incredible experience in the band [One Direction]. And then now, we’ve all got time to express ourselves individually. I’ve been in the industry over a decade, which is mad to think, really. But at the same time, my solo career still feels pretty new to me. So it’s lucky to be so excited, having worked this many years in the industry. All artists, we want to constantly evolve, get better, et cetera.

The new song “Common People” is a big statement—where does that come from?

I grew up in Doncaster, so I’ve got that place to thank for who I am. I’m very aware of that and I love it. So it was important for me to have a song that honored that and gave Doncaster its credit. I dressed it up in the form of a love song. But really, the intention was just to give Donny a moment.

Obviously you’re someone with a really loyal and passionate audience that will follow you anywhere. How does that affect your music?

I never, ever take it for granted that I’m lucky enough with this album to be able to express myself in the way that I want to, with this album, because it was a shift from Walls. Often, other artists might be worried about alienating a fan base if you take a shift. But I’m so lucky to have such a loyal and passionate fan base, like you say, that I didn’t really have that worry going into this record. In my own experience, when I’ve followed my heart musically and done what I love, I feel that’s infectious. So it’s incredible having that kind of fan base, and having the confidence to be able to make a record that I want.

Again, I think it’s a testament to both of us. I look at me and my fans as almost like one collective. I can’t take full credit. I really love the relationship I have with my fans, so I won’t do anything to jeopardize it and I’m always trying to look out for it. Always.

With this album, does it feel like there’s a continuity with what you’ve been doing from the beginning? Does it feel like it’s you all the way through?

Oh yeah, I definitely do. It’s kind of a break free of who I was in the band [One Direction]. And that’s not to say I wasn’t myself in the band, but when you’re a young lad in a situation like that, I don’t care fucking how mentally tough you are, there is an element of you trying to fit a brief. And some people are putting that pressure on you. But I would say, there was an element of dumbing myself down a little bit, and being one of four or five. Whereas now, I’m lucky enough to be able to just express myself individually. And I think that’s what this album has done.

I mean, one thing that doesn’t normally happen from a band—there’s normally a couple of people that do all right out of it, but to see *everyone* doing so well is incredible. And I think that is down to individual identity, and also us being quite different. That’s quite interesting—the fact that we fit together as a band, but when you listen to our own music, it’s quite different.

That was something that was really important to me, because it’s not that the first record lacked identity—I just think it was a little bit confused at times about what it was. Where this album, I think it’s pretty clear. I do think it’s a good expression of me, what I like musically, who I am as a person. It’s been challenging at times, but I think you’ve got to take it all with a pinch of salt. It’s the easiest way to stay sane, really.

#lt press#lt interview#rolling stone#11.11.22#fitf promo#rob sheffield#common people#doncaster#1d mention#dmas#dumbing myself down#my repost

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

ROB SHEFFIELD TAYLOR BOOK??!?!!?!?!?!?!

#i love rob sheffield#i mostly read his stuff on the beatles but I know swifties tend to like/feel like he is one of the good writers in relation to taylor so !!#rob sheffield#heartbreak is the national anthem

2 notes

·

View notes