#rorty

Text

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

«La concepción que estoy presentando sustenta que existe un progreso moral, y que ese progreso se orienta en realidad en dirección de una mayor solidaridad humana. Pero no considera que esa solidaridad consista en el reconocimiento de un yo nuclear —la esencia humana— en todos los seres humanos. En lugar de eso, se la concibe como la capacidad de percibir cada vez con mayor claridad que las diferencias tradicionales (de tribu, de religión, de raza, de costumbres, y las demás de la misma especie) carecen de importancia cuando se las compara con las similitudes referentes al dolor y la humillación; se la concibe, pues, como la capacidad de considerar a personas muy diferentes de nosotros incluidas en la categoría de “nosotros”. Esa es la razón por la que he dicho, en el capítulo cuarto, que las principales contribuciones del intelectual moderno al progreso moral son las descripciones detalladas de variedades particulares del dolor y la humillación (contenidas, por ejemplo, en novelas o en informes etnográficos), más que los tratados filosóficos o religiosos.»

Richard Rorty: Contingencia, ironía y solidaridad. Ediciones Paidos, pág. 210. Barcelona, 1991

TGO

@bocadosdefilosofia

@dies-irae-1

#richard rorty#rorty#contingencia#ironía y solidaridad#moral#progreso moral#ética#solidaridad#yo#yo nuclear#esencia humana#nosotros#diferencia#diferencias#“nosotros”#dolor#humillación#novela#novelas#literatura#etnografía#tratados etnográficos#concepciones universalistas#concepciones esencialistas#concepción historicista#teo gómez otero

11 notes

·

View notes

Note

What piece of art (book, music, movie, etc.) most influenced the person you are today?

I. A long prologue on the preconditions of an answer

Thanks for the great question: it's also a hard question to answer! (I've answered a similar question here, but this answer is quite different.) Already at the start, I have to avoid three traps in answering.

The first is including works I've been puzzled and fascinated by, but do not fully understand and so have not been sufficiently influential in the way I'm thinking of. (Examples: Jung and koans. I can talk about them with some plausibility, but do I really understand them? Being honest with myself, I don't.)

The second is including works which easily come to mind because I've enjoyed them, but which haven't been sufficiently influential either. (Lots of science fiction I've read fall under this category.) The third is making a list solely of classics, since I run the risk of making an uninformative list of what everyone already knows---or even worse, having classics simply because they are high-prestige. (Examples: the Epic of Gilgamesh, the Three Kingdoms.) Having said that, many classics have been genuinely influential in my life, and I'll mention some of them later. But I want to make sure that I include more than just classics.

Even while avoiding these traps, I find some difficulties in answering for two more reasons. First, because I haven't been influenced by any single piece of art in particular so much as I've been influenced by artistic works in general.

Second, because even more influential has been my general attitude towards art and culture (to go up a level) rather than any works of art in themselves.

To name some of these attitudes:

I think that the best way to experience artistic works is in their context, by seeing what they're reacting to and against; I think it's useful to see artistic works as part of a coherent tradition for that reason (and this is also why theory is useful).

I don't think you can get a pure experience of artworks, but that they're always shaped by (often invisible) interpretive lenses; I think the best art is transformative (a very Xunzian view); I think there are no compulsory works of art because of this. What transforms each person is different, just because each person is different.

One of my favourite quotes here is from Borges (quoted in the epilogue to Professor Borges; the original citation is to the 1979 interview Borges para millones):

I believe that the phrase “obligatory reading” is a contradiction in terms; reading should not be obligatory. Should we ever speak of “obligatory pleasure”? What for? Pleasure is not obligatory, pleasure is something we seek. Obligatory happiness! We seek happiness as well.

For twenty years, I have been a professor of English Literature in the School of Philosophy and Letters at the University of Buenos Aires, and I have always advised my students: If a book bores you, leave it; don’t read it because it is famous, don’t read it because it is modern, don’t read a book because it is old. If a book is tedious to you, leave it, even if that book is Paradise Lost—which is not tedious to me—or Don Quixote—which also is not tedious to me. But if a book is tedious to you, don’t read it; that book was not written for you.

Reading should be a form of happiness, so I would advise all possible readers of my last will and testament—which I do not plan to write—I would advise them to read a lot, and not to get intimidated by writers’ reputations, to continue to look for personal happiness, personal enjoyment. It is the only way to read.

II. Donald Richie's Japanese Portraits

Having given that very long disclaimer, if I had to select just one work which has been most influential to me and which isn't a well-known classic, it would be Donald Richie's Japanese Portraits. (If you'd like to read even more on this, @transientpetersen has reviewed it here and I've added some comments on its impact on me here.)

Richie's Japanese Portraits combines so much of what I like and has influenced my style (to the extent to which I have one) and taste: short vignettes with psychological insight, fragmentary pieces which add up to a greater whole even if there's never a unitary picture being painted. It led me to other similar authors (like Italo Calvino, Lydia Davis, Kurt Vonnegut, Sei Shōnagon and Yoshida Kenkō and the zuihitsu/xiaopin genre. . .)

And---most importantly---reading the book was one of the events in my life that taught me how to notice people, how to love them. (I can vividly remember a time when I was very bad at both, and it was only with great effort from those around me that I managed to learn to love. And, of course, the influence of the book pales in comparison to the influence of the people who loved me, loving people, lovely people. Love is both attention and action, and I'm still learning.)

Richie has a gift for encapsulating the universal in the particular. Reading the book made me a better person, and that's the highest compliment I can give any piece of art.

III. Other works

Having tried to pick a most influential work, I would be remiss not to mention the many others that have influenced me, often to the same extent. I'll name just a few which immediately come to mind rather than give a full list. Much like William H. Gass's list, I'd probably come up with a different list on a different day.

There isn't any visual art or music on the list---not because of their lack of worth (Philip Glass, Ryuichi Sakamoto, Nils Frahm, Ólafur Arnalds, Oasis, Mahler, and Shostakovich are all personally enjoyable and were influential at particular points!), but simply because I find it easier to cite, explain, and engage with texts, and so texts have been most influential for me. If you're interested, here's a bit on my musical tastes. Now, back to the list:

The Epic of Gilgamesh: Gilgamesh's faults are entirely human; it's a consoling book.

Sima Qian's Records of the Historian (read in the Yang and Yang translation): Ostensibly a book of history, but there's an entire ethos there of understanding the moments of rise and descent, of leaving when things are at their peak, of understanding the moment and waiting. I read it as a child and it was extremely influential in affecting how I behave up to now.

The Three Kingdoms (which I write about sometimes): I read this at around the same time as Sima Qian; the figure of Zhuge Liang exemplifies the tensions inherent when you try to combine the ethos of the Records with the actual prevailing situations.

Elizabeth Bishop's "One Art": There are so many times when I've reminded myself, "The art of losing isn't hard to master. . ."

Simon Leys's essay "The Chinese Attitude Towards the Past": It introduced an entirely new way of thinking about preserving history and memory to me.

Sociological theory, especially Weber, Durkheim, Goffman, and Foucault: They've all shaped my understanding of society and normality. I'm extremely sympathetic to the symbolic interactionists. Weber taught me to appreciate bureaucracy a little more, which has made me more patient while waiting on the telephone: now that's influential!

Key figures and texts within the various philosophical traditions: within the Chinese tradition, Xunzi and Dai Zhen; within the Indian tradition, the Dīgha Nikāya and Vasubandhu; within the Anglo-European tradition, Spinoza and Wittgenstein.

Gadamer's Truth and Method: I still don't fully understand it, but I was extremely influenced by his idea of the fusion of horizons. Some parts of it are pure poetry. When I read the passage where he says that nothing returns, I had a shiver down my spine.

Shen Fu's Six Records of a Floating Life: a depiction of love in a time very different from now, and all the more interesting and touching for that. My favourite passage is the part where Shen Fu and his wife Yün acknowledge the social pressures facing them, and talk about how they hope they can change positions in the next life to understand each other and to overcome these pressures:

Once I said to her, ‘It’s a pity that you are a woman and have to remain hidden away at home. If only you could become a man we could visit famous mountains and search out magnificent ruins. We could travel the whole world together. Wouldn’t that be wonderful?’

‘What is so difficult about that?’ Yün replied. ‘After my hair begins to turn white, although we could not go so far as to visit the Five Sacred Mountains, we could still visit places nearer by. We could probably go together to Hufu and Lingyen, and south to the West Lake and north to Ping Mountain.’

‘By the your hair begins to turn white, I’m afraid you will find it hard to walk,’ I told her.

‘Then if we can’t do it in this life, I hope we will do it in the next.’

‘In our next life I hope you will be born a man,’ I said. ‘I will be a woman, and we can be together again.’

‘That would be lovely,’ said Yün, ‘especially if we could still remember this life.’

There's so much encapsulated in this short passage: Shen Fu and Yün accept society's limitations while trying to transcend them within a framework they're familiar with, all while dwelling in the care and love and friendship between them. When I read this passage for the first time, I had to stop reading; I had started crying.

IV. On dealing with complexity

Most of the works which come to mind immediately are works of philosophy, theory, or nonfiction. This is no accident.

Life is complex, and there are at least two ways of dealing with the complexity of life. Philosophy tends to make it more explicit (although there are exceptions like Wittgenstein, where the very form of the Philosophical Investigations forces you to think in a particular way) and art tends to make it more implicit (although there are exceptions like programmatic music). In an interview, the philosopher David B. Wong recalls:

I remember taking a number of literature and mathematics courses, besides philosophy. Maybe philosophy combined the appeal of the other two fields for me—the clarity and systematic nature of mathematics and the focus on the human condition in literature.

I have a preference for the explicit, and so I prefer philosophy---but others with a different frame of mind may, for entirely valid reasons, prefer art.

For me, the one great advantage art has over philosophy is its greater pull on the emotions. Art helps build solidarity in a way philosophy doesn't (as Rorty points out). Philosophy does pull on the emotions: I've been happy or had shivers when reading philosophy, and sometimes I've been so excited that I had to get up and walk around before reading further. But I've never cried while reading philosophy, while I have cried before when reading literature.

Thanks for your question again!

10 notes

·

View notes

Link

#richard rorty#richard mckay rorty#rorty#philosophy#pragmatism#philosophy of language#postphilosophy#philosophy of mind#inna besedina#historyandphilosophy

5 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Do We Need Ethical Principles? Richard Rorty (1994)

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hogyan jutottam ide?

Ez a poszt az elsőre része egy két részből álló írásnak, aminek az az összefogó címe: „Hogyan jutottam ide, és hogyan tovább?” A „Hogyan tovább?” lesz, a következő poszt.

A filozófia húszas éveim elején kezdett el érdekelni. Igazából teljesen sznob módon arra gondoltam, hogy kellene valami filozófiát olvasni, és találtam otthon egy Nietzsche válogatást magyarul. Ezt elolvastam és utána olvastam még Nietzschét, de szerintem akkoriban nem igazán értettem. Ahogy olvastam arra gondoltam, hogy igen, ez rendben van, de nekem, mint villamosmérnök hallgató, valami olyasmi kellene, ami filozófia, de közelebb áll a tudományokhoz. Találtam is ilyet, és eléggé össze-vissza kezdtem el olvasni például Quine-t, Russellt, Wittgensteint, talán pár Frege esszét. Továbbra sem hiszem, hogy igazán értettem is volna, amit olvasok. Russell szerintem érthető volt, legalább is a „A filozófia alapproblémáira” úgy emlékszem vissza, mint jó, érthető olvasmány, bár már részletesen nem emlékszem rá. Persze az „A Denotálásról” elég nehéz írása. Wittgenstein teljesen érthetetlen volt számomra. Quine máig nagyon érdekel, de akkor még nem volt elég háttértudásom, hogy megfelelően megértsem (most sem vagyok benne biztos, hogy ez megvan). Emlékszem például, hogy egy barátom, aki nyelvészhallgató volt mutatta nekem „Az empirizmus két dogmáját”, amit együtt olvastunk el. Valahogy szerintem volt bennünk bizalom, hogy ez fontos, bár nem tudtuk szerintem követni Quine gondolatmentét. Quine hitelességét az is növelte számomra, hogy a nevével a digitális technika tankönyvben is találkoztam, amiben benne volt a „Quine–McCluskey minimalizáció”. Frege esetében máig nem értem miért érdekes probléma a „hajnalcsillag = alkonycsillag”, pontosabban végső soron azt hiszem értem, de itt már kezdett jelentkezni számomra az analitikus filozófiával kapcsolatos bizonyos mértékű kételkedés. Természetesen Frege egy zseni, aki a legfontosabb logikus volt Arisztotelész óta, ehhez kétség sem férhet.

Elkezdtem filozófia témájú kurzusokat is felvenni az egyetemen, ami közül az egyik egy logika kurzus volt. A félév végén a házi feladat az volt, hogy egy filozófia cikkben található érvelést formalizáljunk. Természetesen Quine „Az empirizmus két dogmájához” fordultam, és újfent az analitikus filozófia iránti kételkedésem erőre kapott, amikor kín keservesen megpróbáltam az érveléseket formalizálni, de valahogy azt találtam, hogy pusztán a szigorúan vett formális logika az érveléseknek csak igen csekély részét képes jól megragadni. Szóval eléggé naiv dolognak tűnt számomra, hogy abban bízzunk, hogy a modern logika meg fogja oldani a filozófia problémáit, legalább is én így értelmeztem Russell-t, a korai Wittgensteint és Carnapot, hogy ilyesmiben bíztak.

Alapvetően az foglalkoztatott, hogy miért működnek a természettudományok? Különösen a matematika miért alkalmas a természet leírására? Lenyűgözőnek találtam, hogy a Fourier transzformáció, amivel egy jelet meg lehet jeleníteni frekvencia tartományban, működik, és lehetőséget ad például szűrők tervezésére. Ez az érdeklődésem végül is ahhoz vezetett, hogy egyfajta „végső igazság” birtokába akartam kerülni, amit a tudomány objektivitása fog nekem elhozni. Úgy gondoltam, hogy a fizikai törvényei lesznek ez a fajta végső igazságok és a fizika részecskéi az ontológia. Richard Rorty egészen más formában, de szerintem hasonló indíttatásról ír filozófiai érdeklődésének kezdeteiről a „Trockij és a vad orchideák” című esszéjében. Ő egy olyan látásmódot keresett, ami a személyes különcségeit (a vad orchideák szeretete), és a morális meggyőződéseit (amit Trockij képviselt) egybe foglalja. Ami közös bennünk, bár Rorty sokkal irodalmibb módon fejezi ki, az a menekülés az esetlegességtől, és a végességtől. Az a kvázi-vallásos igény, hogy valami végsőt megértsünk, ami mindennek értelmet ad, és rendet teremt. Végül mindketten csalódtunk: Rorty nem kapta meg a mindent egybefoglaló látásmódot, és én egyre inkább azt kellett, hogy belássam, hogy ha létezne is ez a mindent átfogó fizikai elmélet, az bizonyos szempontból nagyon „kevés” dolgot magyarázna meg. Ez alatt azt értem, hogy a materialista világszemlélet nagyon szegényes, nincsen benne hely sok mindennek, amit az emberiség fontosnak tart. Számomra azonban nem az a megoldás, hogy akkor bővítsük ki az ontológiánkat, értékekkel, számokkal és más absztrakt objektumokkal stb., hanem az, hogy a metafizika, mint kérdésfelvetés elkerülendő. Ez a lelkiállapot nagyon fogékonnyá tett Rorty-ra, és a pragmatizmusra általában is.

Rortytól tanultam azt, hogy elfogadjam a végességet és az esetlegességet, szóval már nem célom a „végső igazságok” kutatása, illetve ehhez kapcsolódóan egyetértek Rorty-val, hogy a filozófia nem tud megalapozni más tudományokat, értékeket (és nincs is erre szükség). Az a vágy, hogy „objektív” megalapozást találjunk, menekülés a végesség elől. („objektív” itt filozófiai értelemben értendő, hogy valami egy az egyben megfelel a valóságnak metafizikai értelemben, és egész biztos, hogy soha nem fog változni. Ha „objektivitás” alatt csak annyi értünk, hogy nagyon alaposan körüljártok a kérdést, és ez tűnik a legjobb megoldásnak jelenleg, akkor nincsen a kifejezéssel problémám.) A tudományok sikerei önmagukért beszélnek, érdekes lehet bizonyos kérdésekről „filozofikusabban” elgondolkodni, például Tim Maudlin két kötetes „Philosophy of Physics” című könyve szerintem nagyon érdekes olvasmány, ami segít megérteni a fizikai elméleteket. (Itt nyilván feltételezem, hogy a filozófus érti, amiről beszél, és nem csak ezoterikus hókuszpókuszra használja a fizikát, amit igazából nem ért.) De nincs szükség és nem is lehet a fizikát filozófiailag megalapozni, szerintem ez ma már nem egy vitatott állítás.

Morális, etikai vagy politikai eszmék tekintetében is egyetértek Rorty-val amikor azt mondja például, hogy a demokrácia az eddigi legjobb ötlet, egy állam működtetésére, de ez egy történelmi szerencse, hogy így alakult, és nem mondjuk, az emberi természet mélyebb megértéséből adódik. A demokrácia működik, a világot sokkal jobbá tette, én nem nagyon látom, ezt hogyan lehetne elvitatni, és ha ez nem elég érv mellette, akkor nem tudom, mi lenne jobb.

A másik kapcsoló vonal a személyes politikai meggyőződésem. Mindig is baloldalinak gondoltam magam, szóval ez megint egy pont, ami közös Rorty és köztem. De szintén húszon éves koromra rájöttem, hogy a politikai nézeteimet nem tudom igazán jól megvédeni, és ezért elkezdtem foglalkozni a politikával és a közgazdaságtannal. Ezen a területen Pogátsa Zoltán írásai segítettek nekem a legtöbbet eligazodni.

#philosophy#filozófia#Rorty#richard rorty#Pogátsa Zoltán#Analitikus Filozófia#pragmatism#pragmatizmus#john dewey

1 note

·

View note

Quote

Before Kant, an inquiry into "the nature and origin of knowledge" had been a search for privileged inner representations. With Kant, it became a search for the rules which the mind had set up for itself (the "Principles of the Pure Understanding"). This is one of the reasons why Kant was thought to have led us from nature to freedom. Instead of seeing ourselves as quasi-Newtonian machines, hoping to be compelled by the right inner entities and thus to function according to nature's design for us, Kant let us see ourselves as deciding (noumenally, and hence unconsciously) what nature was to be allowed to be like. Kant did not, however, free us from Locke's confusion between justification and causal explanation, the basic confusion contained in the idea of a "theory of knowledge."

Richard Rorty, Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature

#philosophy#quotes#Richard Rorty#Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature#Kant#belief#representation#justification#causality#knowledge#epistemology

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

I don't think you need to have language prior to having concepts, in fact I struggle to find words that exist for emotions and thoughts I have all the time. You're taking the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis entirely too seriously.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

#philosophy#quotes#Richard Rorty#Consequences of Pragmatism#Rorty#life#self#being#internality#knowledge#belief#faith

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

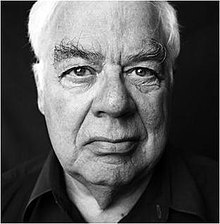

One time—it was the only time I ever taught Lolita!—I assigned a chapter from this book and used the cover, specifically Rorty's facial expression, to explain his philosophy. The tight smile on his face represents his amused resignation to the contingency and irony of the world as celebrated by such playful authors as Nietzsche, Derrida, and Proust, while the unmistakable sorrow in his eyes shows his knowledge of the suffering in the world and the consequent need for solidarity, as called for by such writers as Marx and Mill, Dickens and Orwell—a synthesis of smiling mouth and haunted eyes recapitulated in the subliminally mournful hijinks of Lolita itself. I don't remember if the students were persuaded. I didn't know it when I made the syllabus, but they were all PSEO students and therefore about 16 years old, so, between being assigned Lolita and hearing this kind of thing, I think they were just in a state of, "Whoa...college."

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

phenomenological epigraphy

Juhani Pallasmaa’s The Eyes of the Skin

also, Sartre’s ocularphobia

#Juhani Pallasmaa#The Eyes of the Skin#johann wolfgang von goethe#friedrich nietzsche#richard rorty#jorge luis borges#maurice merleau ponty#jean paul sartre

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rick and Morty intro

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

does anybody want to come and hit me over the head with a rock so i don't have to do this fucking philosophy essay

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

rick and morty but they swapped outfits so now its mick and rorty. thanks for coming to my ted talk.

also i have never seen an arm before in my life. what even is that. an arm? never heard of it. hands? nope. never. also im back on my no background shit. takes too much brain power and i had a bad day today so 🤷♂️.

anyway enjoy!!

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

A tényrelativizmus mérése Magyarországon

A Political Capital közölt egy tanulmányt (itt érhető el), amiben arra keresik a választ, hogy „a tényrelativizmus jelensége hogyan jelenik meg a hazai közvéleményben”. „Tényrelativizmus” alatt pedig „a tények létezésével és megismerhetőségével kapcsolatos erősödő kételyt” értik a szerzők.

Ezt a fajta tényrelativizmust úgy gondolják a média iránti bizalmatlanság váltja ki. Magyarországon a bizalom a média iránt rendkívül alacsony: „A médiába vetett bizalmatlanság vonatkozásában Magyarország az élvonalba tartozik: mindössze 25% bízik a médiában, ami a Reuters Intézet kutatása alapján a második legalacsonyabb arány az általuk vizsgált 46 országot felölelő globális mintán.”

A kutatásban öt állítás esetében kérdezték meg az embereket mennyire értenek egyet az adott állítással. Egytől ötig terjedő skálán lehetett válaszolni, ahol az egyes az „egyáltalán nem ért egyet”, az ötös a „teljes mértékben egyetért”. Minél magasabb pontszámot „ér el” így az ember, annál inkább tekintik a kutatásban tényrelativistának az illetőt.

Érdekesnek találom, hogy végső soron egy filozófiai álláspont elterjedtségét próbálja a tanulmány mérni ezért, arra gondoltam írok néhány megjegyzést az állításokhoz, amikről az embereket kérdezték.

Nem lehetünk biztosak abban, hogy amit tényként közölnek, az igaz is.

Ez egy triviális 5 pontos kérdés, teljesen magától értetődő, hogy ha valaki valamit tényként közöl, attól még tévedhet, vagy hazudhat. Nem értem ez miért mozdítana bárkit is a tényrelativizmus felé. Ugyanakkor nem tisztázott, hogy ki közli a feltételezett tényt: ha megbízhatónak tekintem a forrást, inkább fogom elhinni. Ez az állítás szerintem nagyon rossz, mert szerintem szimplán józan ész ezzel egyetérteni.

Sok dolog, amire tényként hivatkoznak a sajtóban, valójában csak egy vélemény.

Itt úgy érzem, nagymértékben befolyásolhatja a válaszadókat az, hogy kifejezetten a sajtóban hivatkozott dolgokra szűkítették az állítást. Kíváncsi vagyok, ha úgy fogalmazták volna meg, hogy „Sok dolog, amire tényként hivatkoznak, valójában csak egy vélemény.” milyen eredmény született volna. Felmerül a kérdés, mit akarunk mérni? A tényrelativizmus, mint filozófiai gondolkodás elterjedtségét, vagy a médiába vetett bizalmat? Ha az előbbit, akkor a módosított kérdést kellene feltenni, ha az utóbbit, akkor jó így. Azonban ha valaki azt állítja, hogy aki a fenti állítással egyetért, tényrelativizmusról tesz tanúbizonyságot, annak szerintem azt lehet válaszolni, nem, pusztán szkeptikus a sajtó megbízhatóságát illetően.

A „sok dolog” kifejezés is érdekes az állításban, mert ha valaki valóban tényrelativista, akkor bármi, amire tényként hivatkoznak valójában vélemény, hiszen tények egyáltalán nincsenek. Egy tényrelativista lehet, épp azért nem értene egyet ezzel az állítással, mert nyitva hagyja a lehetőségét annak, hogy bár sok dolog vélemény és nem tény, azért lehet, hogy van olyan, ami tény és nem vélemény, csak kevés ilyen van.

Az „igazság” valójában az az álláspont, amit az ember magának választ.

Ezt az állítást vegyük kétfelé: a, Az „igazság” az álláspontunk függvénye; b, Ezt az álláspontot az ember önkényesen magának választja. Ugyan az eredeti állítás nem tartalmazza az „önkényes” kifejezést, én azért tettem itt bele, mert úgy gondolom, hogy igazából erre vagyunk kíváncsiak, hogy az emberek úgy gondolnak-e az igazságra, mint amit mindenki magának tud eldönteni, bármi másra tekintet nélkül. Tegyük fel, hogy elfogadjuk a-t, de elutasítjuk b-t, és azt mondjuk az igazság az álláspontunk függvénye, de ez az álláspont nem egy egyénileg, önkényesen meghozott döntés, hanem egy közösségileg ellenőrzött döntés. Nem pusztán arra gondolok, hogy a többség álláspontja lesz elfogadva, hiszen nem is így éljük mindennapjainkat: gyakran hagyatkozunk egy szakértő kisebbségre (helyesen) olyan speciális esetekben, ami szakértelmet igényel (orvosok, fizikusok, stb). Aki így gondolkodik, az például el fogja fogadni a tudomány jól megalapozott állításait igaznak, mert azt mondja, a tudományos álláspont a legmegbízhatóbb, ami jelenleg elérhető. De mivel a tudományt emberek művelik, sosem leszünk olyan helyzetben, hogy kijelentsük, hogy ez most már a „végső” igazság. Ha valaki elfogadja a-t és b-t is, az joggal nevezhető tényrelativistának, hiszen ez az ember azt gondolja, hogy az igazság egyénileg, önkényesen eldönthető, mindenféle konzultáció nélkül másokkal. Aki valóban tényrelativista erre a kérdésre 5 pontot kell, hogy adjon. Aki tény realista 1-et, és aki a fenti gondolatmenettel egyetért, az vagy nem válaszol, vagy valami köztes értéket fog választani.

Objektív valóság valójában nem létezik, csak különböző vélemények vannak.

Szerintem a ki nem mondott feltevés az állítás hátterében az, hogy ha nincs objektív valóság, akkor nem lehetünk kritikusok senki véleményével kapcsolatban, hiszen nincs olyan neutrális álláspont, amiből el lehetne dönteni, kinek van igaza. Ez az állítás egy fals dichotómia. Nem úgy kritizálunk másokat, hogy mi birtokában vagyunk az objektív valóság ismeretének, és ez alapján meg tudjuk mondani, hogy ki téved és ki nem. Mi ugyanúgy tévedhetünk, szóval az „objektív valóságra” való hivatkozás felesleges. Amikor vélemények ütköznek, akkor mindkét fél feladata az, hogy érvekkel támassza alá, hogy miért gondolja igaznak, amit mond. Ha valaki azt mondja: „nekem van igazam, mert ez az objektív valóság”, akkor igazából semmilyen érvet nem hozott fel. Ez csak egy retorikai fogás, amivel bárki élhet. A kérdés az, szükségünk van-e egy „objektív valóság” feltételezésére, mint egy vezérfonálra. Richard Rorty a mellett érvel, hogy nincs (Richard Rorty : „Is Truth A Goal of Enquiry? Davidson Vs. Wright”). Nem tudom eldönteni mikor értem el az „igazságot”, ezért nem is tudom „megcélozni” az igazságot. Amit tudok az az, hogy kellően jól igazoltak-e a hiteim, amit úgy tudok elérni, hogy mások véleményét is kikérem. Nyilván nagyon alapvető dolgokat le tudok ellenőrizni magam is, de bonyolultabb tudományos állításoknál szükség van egy tudósokból álló közösségre, akik megpróbálnak kritizálni elméleteket, reprodukálni kísérleteket, vagy új kísérleteket kitalálni. Aki tényrelativista 5 pontot fog adni erre az állításra, aki tény realista 1-et, de azt szeretném megmutatni ennél az állításnál, hogy nem csak ez a két lehetőség létezik. Ez az állítás a szekuláris változata annak, hogy „Isten nélkül mindent lehet”, ami már kiderült, hogy egy hibás elképzelés volt, és erről az állításról is szerintem ki fog derülni, hogy téves.

Aki azt állítja, hogy tudja mik a tények, valójában hazudik.

Furcsa az állítás, mert nem engedi meg, hogy az illető, aki azt állítja, tudja, mik a tények egyszerűen téved. Nem tudom, ez az állítás mennyire jól méri az emberek tényrelativizmus hajlamát. Még ha tény relativista is vagyok, nem feltétlenül kell azt mondanom, hogy aki ezt állítja, hazudik, és nem egyszerűen csak téved. Például, mert meg lett vezetve, és azt hiszi, hogy tények léteznek. Így akár 1 pontot is adhatok rá.

Mennyire tűnnek az állítások jónak a tényrelativizmus felmérésére? Az első állítás triviálisan elfogadható, és semmilyen tényrelativizmusra nincs szükség, hogy egyetértsünk vele. A második állítás inkább a sajtó iránti bizalmat tükrözi, mint a tényrelativizmust. A harmadik és negyedik állítások jó szűrőnek tűnnek alapvetően. Az ötödik megint nem tűnik jónak, mert nem engedi meg, hogy a tényeket állító személy egyszerűen tévedett. Szóval összességében ötből három állítás nekem nem tűnik alkalmasnak a tényrelativizmus mérésére. Illetve nekem úgy tűnik, hogy a kutatás készítői feltételezik a négyes állításban levő fals dichotómiát, miszerint vagy hiszünk a tények objektivitásában, vagy relativisták vagyunk, és nincs más lehetőség. Az írásomban azt szerettem volna bemutatni, hogy nem csak ez a két út lehetséges.

2 notes

·

View notes