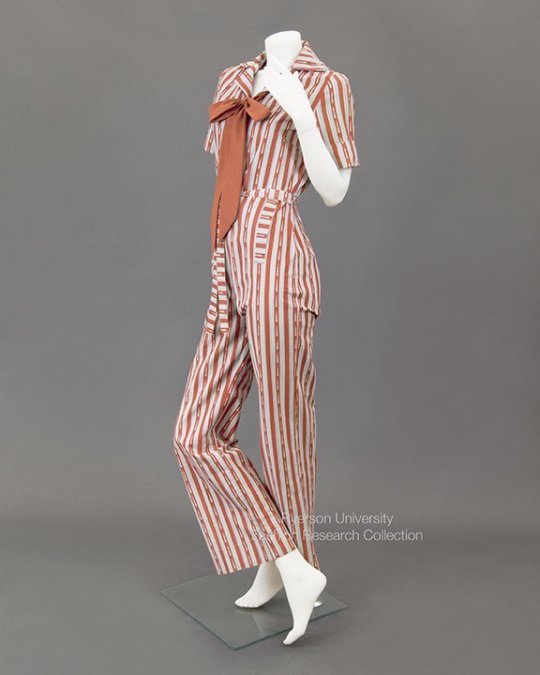

#ryerson university fashion research collection

Photo

Up Close: Reproduction 1880s Dress (Ryerson University Fashion Research Collection)

#fashion history#historical photos#1880s#19th century#costume#brown#velvet#ryerson university fashion research collection

203 notes

·

View notes

Text

Stolen Goods: Plagiarism and Fashion Scholarship

Stolen Goods: Plagiarism and Fashion Scholarship

“Arsenic Dress”: English or French, c. 1860s The Fashion Research Collection at Ryerson University. Gift

The Racked website, recently published a piece on toxic clothing that appears to be an unattributed reproduction of a body of work by Ryerson University fashion scholar Dr. Alison Matthews David.

The Racked post even includes a photo of the arsenic dress from the popular “Fashion Victims”…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Facebook profits from Canadian media content, but gives little in return

Fb CEO Mark Zuckerberg testifies earlier than a Home Monetary Companies Committee listening to on Capitol Hill in Washington, on Oct. 23, 2019, on Fb's impression on the monetary companies and housing sectors. (AP Photograph/Andrew Harnik)

It’s a promise I can’t wait to see fulfilled. In its most up-to-date speech from the throne, Justin Trudeau’s authorities pledged to make sure the income of internet giants “is shared extra pretty with our creators and media.”

As a journalism professor, I believe that’s nice information for Canadian journalists. Canadian media have been struggling previously decade — and greater than 2,000 jobs have been misplaced because the begin of the COVID-19 pandemic.

However how a lot will the contributions from digital platforms quantity to? How can we calculate what information is value for them?

Placing a greenback worth on information

I’ll give attention to Fb, each as a result of we will extract Canadian revenues from its monetary paperwork and likewise as a result of it doesn’t have a revenue-sharing mannequin.

For the primary two quarters of 2020, Fb reported revenues of US$924 million in Canada alone. Over 2018 and 2019, Fb made almost $6 billion in Canada.

It must be famous that just about 98 per cent of this turnover comes from promoting gross sales — it’s the identical good previous enterprise mannequin that has sustained information media for the previous 200 years, however Fb has tailor-made it for the digital age utilizing emotional manipulation.

To seek out out what quantity of this consideration is the results of journalistic content material, I used CrowdTangle, a public insights software provided by the corporate to search for content material on Fb, Instagram and different social networks comparable to Reddit. Researchers have been capable of entry it since 2019, underneath a partnership with Social Science One.

Amongst different issues, CrowdTangle gives entry to the 30,000 publications that generated probably the most interactions over a given time frame. Interactions are the sum of shares, reactions (like, love, wow, haha, anger, unhappiness and, extra not too long ago, care) in addition to feedback. The software additionally permits you to prohibit your search to pages administered in a given nation.

Calculating revenue

For every of the 30 months within the interval between Jan. 1, 2018, and June 30, 2020, I used CrowdTangle to determine the 30,000 posts that generated probably the most interactions on pages whose directors are predominantly positioned in Canada. I bought 900,000 Fb posts from simply over 13,000 completely different pages. Of those, near 500 pages belong to information media. Collectively, they posted nearly 80,000 objects.

This implies media pages have accounted for 8.9 per cent of the Canadian content material on Fb pages. This proportion of the corporate’s Canadian gross sales represents greater than half-a-billion {dollars} since 2018.

Variety of publications by language and web page class, from January 2018 to June 2020.

(Jean-Hugues Roy), Writer supplied

Having stated that, we should take into consideration the truth that Fb doesn’t generate income merely when a submit is revealed, however when folks work together with this content material by sharing it, liking it or commenting on it. So let’s check out how interactions are distributed by language and web page sort since Jan. 1, 2018.

Variety of interactions triggered by Canadian Fb web page postings, by language and web page class between Jan. 1, 2018, and June 30, 2020.

(Jean-Hugues Roy), Writer supplied

Out of greater than 7.6 billion interactions, greater than 400,000 had been triggered by journalistic content material. That’s 5.three per cent of the full.

This fashion of calculating, which weighs the place of journalistic content material by the bottom variety of interactions it generates, nonetheless implies that the Canadian media have enabled Fb to boost almost a 3rd of a billion {dollars} over the previous two and a half years.

The gulf between Fb and the media

In fact, my research has its limits. Fb generates income in Canada when advertisers purchase adverts to succeed in Canadians. So as to extra precisely measure Fb’s revenues in Canada, it will be vital to look at what content material Canadians are viewing on this social community. However Fb doesn’t share this sort of data. One of the best we will do, due to this fact, is to have a look at what’s produced by pages administered in Canada.

Pals of Canadian Broadcasting ran a marketing campaign referred to as Needed to focus public and political consideration on guidelines that enable Fb to revenue from content material created by Canadian information retailers with out compensation.

THE CANADIAN PRESS/Nathan Denette

In addition to, it’s not solely pages on Fb. There’s additionally content material on teams and profiles. And Fb generates income by means of Instagram, Messenger and WhatsApp. However it’s only attainable to gather nation knowledge by means of the pages.

The primary takeaway from this evaluation is that there’s a gulf between what the media enable Fb to generate as income and what Fb returns to them. Kevin Chan, director of public coverage for Fb Canada, said in Le Devoir not too long ago that Fb has spent $9 million on numerous journalism initiatives in Canada over the previous three years.

Sharing income

There are different methods Fb advantages the media — they’ll monetize their tales by means of “immediate articles,” the place content material stays on Fb in alternate for some income sharing with the media, or the video platforms Watch and IGTV, Fb’s makes an attempt to compete with YouTube.

In america, Fb Information, a brand new licensing mechanism, may enable some main media retailers to earn as much as US$three million yearly.

Fb additionally funds some journalism training initiatives at numerous universities, together with Ryerson College.

Nevertheless, immediate articles have been deserted by many media retailers, and creators making an attempt Watch have gone again to YouTube. In each circumstances, it’s as a result of Fb doesn’t share sufficient of its income.

Australia launched laws that will power Fb and Google to take a seat down with the Australian media and negotiate to share revenues. Canadian Heritage Minister Steven Guilbeault appears to have been impressed by this strategy.

Fb advantages from journalism

Fb has reacted to Australia’s intentions by threatening to dam customers from sharing native and worldwide information. Simply think about Fb with out information: Would we use it as a lot if all we may share with our associates was clickbait?

Making Fb share its revenues would due to this fact be a triple win. First, with a little bit more cash, the media would have the ability to rent extra journalists. I say “a little bit” as a result of I do know Fb alone received’t save the media, however it will actually assist.

Second, the federal authorities (and all Canadians) would win too, as a result of supporting the manufacturing of high quality journalism is a concrete approach to combat misinformation.

Third, Fb would win as a result of Canadians would have higher assurance that it will be a supply they’ll belief for his or her data wants.

Jean-Hugues Roy is a member of the Fédération professionnelle des journalistes du Québec (FPJQ).

from Growth News https://growthnews.in/facebook-profits-from-canadian-media-content-but-gives-little-in-return/

via https://growthnews.in

0 notes

Text

Just How ‘Woke’ is the Fashion Industry?

“’For me, an inclusive industry is not only an inclusive spread of models of various sizes and skin colours; it’s a C-suite that’s as diverse, [and] as inclusive, that has embraced different cultures,’ said designer and advocate Céline Semaan, founder of fashion think-tank Slow Factory and non-profit conference series The Library Study Hall. ’What’s missing right now is an understanding that the barriers preventing inclusion are systemic, so the transformation needs to be systemic,’ said Ben Barry, chair of fashion at Ryerson University in Toronto. “Inclusion isn’t a check mark.”

“This year alone, Gucci’s efforts to market itself as one of fashion’s most “woke” brands stumbled after it released a jumper many consumers said resembled blackface; the fashion director of Vogue Brasil resigned after photos from her 50th birthday party drew criticism for evoking colonial depictions of slavery; Mexico’s government accused Carolina Herrera of cultural appropriation; and Kim Kardashian West had to change the name of her new shapewear collection after the original name, Kimono, sparked outrage in Japan and beyond. ...That’s far from an exhaustive list of misdeeds, but the far-reaching reputational damage and global impact of these issues suggests that brands are operating in a new paradigm. The pressure facing fashion companies to operate more inclusively is a reflection of broader social, political and technological shifts that are creating new opportunities and pitfalls for anyone running a global fashion enterprise.”

“No doubt there are signs of mounting engagement. A chief diversity officer is fashion’s hottest accessory this season, and brands are increasingly talking about HR initiatives intended to improve inclusivity, in part through company-wide training and education. A growing number of fashion companies have committed to hiring processes designed to encourage managers to consider a greater range of candidates and are setting targets for more diversity at the leadership level. Some have recruited celebrities and academics to join high-profile diversity councils aimed at tackling both internal and external challenges within the industry. But consumers and experts have remained healthily sceptical.”

BoF, October 7, 2019: “Fashion’s Long Road to Inclusivity,” by Sarah Kent

STUDY HALL: A global education platform for Sustainability Literacy & Advocacy, Technology and Human Rights

SLOW FACTORY: A design lab working with companies to research & implement sustainability-focused initiatives, from waste recovery to software to manufacturing.

#fashion industry#fashion#diversity#inclusion#cultural intelligence#models#clothing industry#Sustainability#advocacy

0 notes

Text

Vlada Tabachuk - Startup Fashion Week

Startup Fashion Week - Vlada Tabachuk

Vlada Tabachuk is an incredibly talented designer, she is based in Toronto and will be showing a full collection of unique apparel at Startup Fashion Week Runway Show on Oct 25. She is an incredibly talented designer

DO YOU DESIGN YOUR OWN CLOTHES, OR YOU HAVE GO TO LABEL?

I’ve always liked to up-cycle clothes I already had to give them a second life but I rarely make my own clothes from scratch. I’m not really a patron of one particular label and I don’t really subscribe too much to trends. I like to shop around for items that I could see myself wearing forever.

WHEN DID YOU FIRST REALIZE YOU WANTED TO PURSUE A CAREER AS A DESIGNER?

I’ve always known this is what I wanted to do. My life has taken me on a lot of detours but I would always end up doing something fashion related. Once I made the decision to attend the Fashion Design Program at Ryerson University, I started to feel like I was exactly where I was supposed to be and after graduation I just kept trying to start my own brand until my team with an investor found me and approached me.

ARE YOU SELF-TAUGHT OR DID YOU STUDY FASHION DESIGN?

I started sewing things when I was still a kid and tried to learn new techniques as I grew up. The DIY movement and creation of YouTube really helped me learn but I never felt that I could learn as much on my own as I could in a design program so I decided to get a degree from Ryerson University.

WHAT OTHER SKILLS ARE IMPORTANT?

I think the most important skills in any work are the ability to network, ability to multitask, and the ability to adapt. To me networking is how I get inspired by others and how I continue to educate myself in what I do. Being able to multitask is crucial because as a new brand I am always hit with multiple things that are ALL priority and nothing can be put off until later. Lastly, it’s very important to be able to adapt to any changes that have to be made to the original plan when issues arise. My biggest motto through the whole process of starting my own brand when things would not go according to plan has been “Make it work!” (Tim Gunn from Project Runway)

WHAT ARE YOU BIGGEST FEAR WHEN GOING OUT AND STARTING YOUR OWN LINE?

I can’t say there was ever a big fear of failure or disappointment when I was starting the brand with my business partners. Not to say that it wasn’t scary doing everything for the first time like registering a corporation, building a business plan, making big financial decision, creating mass production product etc. but I was never afraid of it turning out differently from how I expected. It’s rare that anything turns out how you expect so I went in ready to adapt and fail as many times as I needed until we figured it out.

WHAT IS YOUR FAVORITE PART ABOUT BEING A DESIGNER?

My favourite part about being a designer is putting on some inspiring jams, spreading a clean piece of white paper on the drafting table and spending the following hours/days figuring out how a garment will be constructed, how every seam will interact with the fabric, how the construction and complexity will drape and interact with a body, how the construction will affect the costs and manufacturing time etc. It’s at this stage that I really get to submerge into my own mind and play with this giant puzzle of sorts.

COULD YOU GIVE ME A DETAILED BREAKDOWN OF THE STEPS IN PRODUCING A COLLECTION...(FROM CONCEPTION TO THE RUNWAY)?

1. Come up with a concept and inspiration.

2. Do market and trend research.

3. Create a mood board that combines your ideas and what the market wants/needs for your collections season.

4. Sketch as many designs as are in your head following your moodboard as inspiration and consistency guide.

5. Choose your final designs and tweak them as needed to ensure they work together as a collection and that the construction of them will remain within your brand’s manufacturing cost bracket.

6. Find your fabrics, trims, and hardware.

7. Create production documents necessary to create patterns for the garments..

8. Started creating garment patterns, testing each one out in muslin and then in actual fabric. At this stage some changes are often made to fabric choices and designs in order to improve the overall appearance and to decrease manufacturing costs where possible.

9. Once the patterns are created, additional manufacturing documents are created that include a record of material quantities per garment, costs, and specifications. They are used for the brand to communicate with manufacturers, calculate production costs, and come up with retail prices for the garments.

10. Create and order care tags, hang tags, size tags, and brand tags.

11. Create double sample of each garment to use for photo shoots and promo while the manufacturer is producing the total quantity.

12. Plan and execute a look book shoot and create a stock of brand photos to use for social media and PR.

13. PROMO! Reach out to your network to share news of your new collection; create exciting and interesting social media posts; go out and be seen/heard; reach out to media to make them aware of this awesome thing you just did and get them excited about your new collection.

14. Get ready for the runway: model try ons, runway moodboards for Hair and Make-up Artists, start stocking up on thank you cards and gift merch.

( I hope this isn’t too much! I tried to condense it to crucial steps.)

HOW WOULD YOU DESCRIBE YOUR BRAND?

Project 313 Apparel is a luxury street wear brand that is heavily inspired by techwear through it’s use of fabrics, fit, and function. I like to create items that stand out through small design details and manufacture them in fabrics that are both eco-friendly and unbelievably soft to the touch.

WHERE DO YOU GO FOR INSPIRATION?

I find the most inspiration just wandering around busy the streets and observing. Toronto is a fantastic city for that because of the vast diversity in architecture, culture, people, styles, tastes, music. I got design on my mind and my mind on design 24/7 so it’s never hard to find inspiration. I can look at any object and visualize an article of clothing that reflects it’s vibes or aesthetic so Toronto is truly a never ending supply of inspiration.

WHAT ARE YOU FASCINATED BY AT THE MOMENT AND HOW DOES IT FEED INTO YOUR WORK?

I am currently obsessed with exploring untraditional and challenging construction techniques. I am a glutton for a challenge. Our launching collection called Order x Chaos for Project 313 Apparel features some complicated style lines that are unconventional for hoodies and tees. It was a challenge to create an odd hood shape that looks like it sits on your shoulders but I love how it turned out.

HOW DO YOU WANT YOUR CLIENT FEEL WHEN WEARING YOUR CLOTHES?

We want the Project 313 Apparel customer to feel like they are draped in luxury and comfort when they are wearing our clothing. It is important to us that our clothes inspire confidence and become an extension of self. I think there is nothing worse (clothes related) than being constantly aware of what you are wearing because of a bad fit, uncomfortable fabric, or restricted movement that’s why Project 313 Apparel provides style that allows it’s wearer to be free to move.

HOW WOULD YOU DESCRIBE YOUR PERSONAL STYLE?

I would describe my personal style as “always in transition”. Although I don’t generally follow trends and on average buy only 5 new fashion items every year, I am constantly trying to reinvent my style through finding new ways to wear the pieces I already have. So my style is essentially a rotation of basic with a few oddly patterned pieces. For example some of my favorites are: pants with floral water colour print from Banana Republic, a men’s button up with ice-cream pops I found at winners, a Clover Canynon pull-over sweatshirt with interior design CAD graphic. One day I will fully commit to funky patterns but for now I feel like my collection is just not big enough.

IF YOU WERE A SUPERHERO, WHAT KIND OF POWERS WOULD YOU HAVE?

If I were a superhero I would want the ability to clone myself like Dr Manhattan (without the public nudity) so that I could do more at the same time.

IN YOUR OPINION, WHICH SUPER VILLAINS NEEDS FASHION ADVICE?

If I had to pick one... Doc Ock is probably in the bottom 10. His costume is just a bit boring. He looks like a middle school math teacher, stuck on primary colors, who also forgot it was Halloween so he pulled together a last minute “zucchini” looking outfit. His outfit is just not fear inducing whatsoever so he would really benefit from a makeover.

#Fashion Designer#Fashion Show#Fashion Week#fashion#Fashion#Startup#Startup Fashion Week#Startup Fashion#Canada#Canadian Fashion#Canada Fashion#Canada Fashion Week#Vlada Tabachuk#Vlada#Tabachuk#Project 313

0 notes

Text

Fashion's potential to influence politics and culture

by Henry Navarro Delgado

Political dressing is fashionable right now, but is it fashion?

Celebrities and stars turned up dressed in black at the 75th Golden Globes Award ceremony. Instantly the media was in frenzy over what they dubbed “political fashion statements on the red carpet.” This is just the most recent droplet of a rainy season of purportedly political fashion.

It all started with the pantsuit parties in solidarity with U.S. presidential candidate Hillary Clinton in 2016. It then progressed with white supremacists uniformed in polos and khaki during their infamous Charlottesville demonstrations last year.

As the effects of Brexit, a Donald Trump White House and the rise of so-called alt-right activism in Europe and North America ripple through the cultural waters, political dressing is trending. Protesters of all stripes — feminists, white supremacists, antifa, nationalists and social justice advocates — are outfitting themselves to match their political mindsets.

vimeo

Pantsuit Power flash mob in NYC, Oct. 2, 2016. Video directed by Celia Rowlson-Hall and Mia Lidofsky. Produced by Jillian Schlesinger and Liz Sargent.

This type of political dressing is not the dress code of politicians. This is individuals and groups using everyday dress to express their political outlook. The problem is that often participants and commentators, reporters and scholars, quickly rush to label it fashion. But is political dressing fashion?

What is fashion?

The political dimension of clothing is intuitively understood from the moment individuals are born. Because essentially, human society equals dressed society. What one wears, how one wears it and when one wears it constitutes expressions of degrees of social freedoms and influences.

Dress expression ranges the full political gamut from conformity to rebellion. Simply put, dress style that challenges — or is perceived as challenging, or offering an alternative to the status quo — spontaneously acquires political meaning.

Hence the social power of dress and the political impact of seeing many people dressed in an agreed-upon mode. During the counter-demonstrations in Charlottesville, Va., last summer, antifa protesters opposing white supremacists wore “black bloc” — an all-black uniform of sorts, meant to show a unified hard stance against anti-Black racist discourse.

Simultaneously, “black bloc” dress indicated a willingness to resort to violence if necessary, much like the Black Panthers did in the 1960s and 70s. The Panthers took advantage of a loophole in the second amendment of the U.S. constitution that made it lawful to wear unconcealed firearms in public.

Members of the Black Panther Party argue with a California state policeman at the Capitol in Sacramento after he disarmed them in May 1967. The armed Panthers entered the Capitol protesting a bill before the state legislature would restrict carrying firearms in public. Men in berets at centre are Panther leaders Eldridge Cleaver, left in sunglasses, and Bobby Seale. The policeman holds a weapon taken from the Panthers. (AP Photo/CPArchivePhoto)

Political dressing is a concerted effort by a group of individuals to call attention to a social issue. They do so by dressing in a codified style. The recipe of political dressing has all the ingredients of fashion, but not in the right proportions.

Fashion — as it is defined — occurs when a society at large agrees to a style, aesthetic or cultural sensibility for a period of time. Fashion’s sizeable social scope and requisite expiration date is what makes it so useful as a marker of time.

One sees it used in film, literature or social science research. Thus, fashion means timed changes in taste at a social scale. Fashion occurs in any realm of human pursuits including arts, music, technology, even scholarly discourse and of course, dress.

The source of confusion

We could blame the political dressing vs. fashion confusion on the ubiquitous and pervasive public presence of the contemporary fashion industry. From the 18th century onwards, a large sector of industry has been occupied with manufacturing what dresses us: This includes garments, accessories, beauty services and products. This industry, along with advertisers, coalesced into an all-encompassing fashion industry.

It’s not surprising then, that in today’s globalized world, most people automatically identify clothes with fashion. After all, they are one of the most visible outputs of the fashion industry. Of course, the fashion industry would do nothing to clarify this; it is in their best interest to be perceived as the source of fashion.

That same fashion industry employs a global army of trend forecasters to fine-comb historical records and a multiplicity of current cultural sources and happenings. They use this data to identify what colours, styles and products people would want next season.

More concerning, though, is that fashion scholars are contributing to the public confusion about political dress as fashion. They are interchangeably using the terms dress, style and fashion without regards for their fundamental semantic difference. There is a cultural explanation for this too. Fashion is an emerging scholarly discipline, which makes it very fashionable right now. Slap the word fashion to the title of an academic article or book and readership is likely to follow.

Is political dressing is fashion trend? The #tiedtogether movement used white bandanas to indicate the ‘common bonds of humanity’ Courtesy of The Business of Fashion

The trend of political dressing

Could it be that like fashion studies, political dressing is a fashion trend? Based on the number of collections that included political statements during the 2017 fashion weeks, the answer would be a rotund yes. Several collections during the last season of fashion weeks employed political statements.

Political runway antics included pink pussy hats at Missoni. There were white bandanas as a symbol of inclusion in Tommy Hilfiger, Thakoon, Prabal Gurung, Phillip Lim, Dior and Diane von Furstenberg.

Meanwhile, black berets à la guerrilla or Black Panther uniforms were shown at Dior. As well, all sorts of slogans printed or embroidered in a diversity of garments popped up at Ashish Gupta, Public School and Christian Siriano, punctuated by graphic underwear in LRS’s collection.

This, however, isn’t necessarily good news. The fashion industry has a solid record of co-opting political and countercultural movements, marginalized groups and non-Western cultures, then making a good profit out of it.

There would be nothing wrong with making money this way, except that the aftermath of co-option by the fashion industry is cultural irrelevance. Just like other goods, fashion must be consumed before its expiration date.

The good news is that political dressing may be fashionable, but it isn’t fashion. Not even the global fashion industry can prevent individuals from using their dressed bodies as a tool for political discourse.

So go ahead, pick your preferred political graphic T-shirt or wear the colours of your party of choice. Just remember that isn’t fashion, unless most everybody else decides to dress the same for a while. In which case, your options are: Embrace your fashionable status or change either your outfit or political affiliation.

Henry Navarro Delgado is an Assistant Professor of Fashion at Ryerson University

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

0 notes

Text

7-2 | Table of Contents | DOI 10.17742/IMAGE.VOS.7-2.5 | HallidayPDF Coming Soon!

[column size=one_half position=first ]Abstract | Since the mid-2000s, street style blogs have documented individualized fashion in international cities. With their rise to prominence, photo-bloggers turned their lenses towards mobilities outside fashion show venues in the dominant industry capitals. Fashion Month is the bi-annual circuit of women’s ready-to-wear presentations in New York, London, Milan, and Paris. Each Fashion Week is an enactment of what fashion scholars, pace Pierre Bourdieu, term the field of fashion (Entwistle and Rocamora). This exclusive assemblage can also be described as a scene. This article contends that the circulation of media representations of fashion show attendees, under the banner street style, appropriates a contested term and reinscribes fashion’s elitist social and material ideals. I examine the career of Canadian photographer Tommy Ton and perform content analysis on photographs captured from the Spring/Summer 2014 and Fall/Winter 2014 seasons posted to Condé Nast Media’s Style.com. I trace the term street style to its definition as fashion “observed on the street” (Woodward) and to historical references to subcultures. I then situate online street style photography within a history of depictions of citizens in urban locations and contestations between the “real” and the “authentic” in editorial fashion. Combining Gillian Rose’s notion of social modality with Agnès Rocamora’s fashion media discourse analysis, I describe how Ton’s aesthetic combines non-place-specific architecture with ideal bodies and luxury signifiers to communicate social distinction. Ton’s photographs do not foreground features of cities but rather depict the literalized street itself as a status signifier—an editorial backdrop against which to emphasize fashions.[/column]

[column size=one_half position=last ]Résumé | Depuis le milieu des années 2000, les blogues de mode de rue ont documenté la mode individualisée dans les grandes métropoles. Leur popularité ne cessant d’augmenter, les photographes de rue et blogueurs se sont tournés vers l’évolution du style vestimentaire, et ce, en dehors des défilés des capitales mondiales de la mode. Le Mois de la mode est un événement bisannuel consacré au prêt-à-porter féminin avec des présentations à New York, Londres, Milan et Paris. S’appuyant sur les travaux de Bourdieu, les spécialistes de la mode soutiennent que chaque Semaine de la mode est une matérialisation du domaine de la mode (Entwistle and Rocamora). Ce rassemblement exclusif peut également être décrit en tant que scène. Cet article soutient que la diffusion des représentations médiatiques des spectateurs des défilés de mode, sous la bannière mode de rue, s’approprie un terme contesté et réinsère les idéaux sociaux et matériels élitistes de la mode. J’examine la carrière du photographe canadien Tommy Ton et je réalise une analyse de contenu avec les photographies prises durant les saisons Printemps/Été 2014 et Automne/Hiver 2014 et publiées sur Style.com de Condé Nast Media. J’examine le terme mode de rue selon sa définition de mode « observée dans la rue » (Woodward) et selon les références historiques aux sous-cultures. Je contextualise ensuite la photographie de mode de rue en ligne selon les représentations des citoyens dans les lieux urbains, mais aussi en fonction des contestations entre le « vrai » et l’« authentique » dans la mode éditoriale. En combinant la notion de modalité sociale de Gillian Rose avec l’analyse du discours de la mode dans les médias d’Agnès Rocamora, je décris la façon dont l’esthétique de Ton réunit l’architecture sans lieu spécifique avec des symboles de corps parfaits et de luxe afin de communiquer la distinction sociale. Les photographies de Ton ne mettent pas en évidence les caractéristiques des villes, mais représentent plutôt la rue elle-même en tant que symbole identitaire : une toile de fond éditoriale qui permet d’accentuer les modes.[/column]

Rebecca Halliday | York and Ryerson University

HOMOGENIZING THE CITY/ RE-CLASSIFYING THE STREET:

Tommy Ton’s Street Style Fashion Show Photographs

The Italian fashion editor Anna Dello Russo perches on a red motorbike. She sports a sweater dress and a quilted leather purse in a near-identical shade, emblazoned with what appears to be McDonald’s “golden arches” logo but is actually a doubled signifier for the Italian brand Moschino (Fig. 1). Dello Russo’s look debuted during Fall/Winter 2014 Milan Fashion Week, where Moschino’s collection received criticism for its mix of high and mass culture icons. However, the sole clue that this photograph has been taken in Milan is the motorbike, a common mode of transportation in Italian cities; the name Deloitte, the international financial firm, is visible on mirrored windows that reflect brick facades. This photograph is one of 386 images that Canadian-born Tommy Ton captured of attendees at the Fall/Winter 2014 presentations and posted to Condé Nast Media’s Style.com under the banner street style. The “Big Four” Fashion Week circuit refers to the biannual showcase of women’s ready-to-wear collections in New York, London, Milan, and Paris—the complete series is termed Fashion Month. From 2009 to 2015, Ton captured thousands of photographs of the outdoor scenes of Fashion Month, in addition to Paris Couture Week and smaller-scale fashion weeks in other international cities.[i]

Fig. 1

In a phenomenon known as the street style parade, in-house and freelance photographers compete to document attendees’ and models’ ensembles as they enter and leave Fashion Month venues. Street style blogs, the medium from which this spectacle arose, claim to capture the fashions of “real” people on the streets of international cities. Following the medium’s rise to popularity in the mid-2000s, fashion publications offered photographers lucrative contracts to contribute street style images from Fashion Month to enhance collection reportage. This article examines Tommy Ton’s photographs for Style.com to interrogate the media representations of fashion show attendees and the class politics communicated in the metropolitan streets on which Fashion Month materializes. I contend that these photographs, and their inclusion in press content, appropriate the contested term street style as a site on which to inscribe fashion’s elitist social, material, and embodied ideals. I further scrutinize depictions of Fashion Month cities to situate the clothes within fashion’s internationalization under neoliberalism. Fashion’s consecration of the Fashion Month insider photograph as palimpsest has disconnected the medium of street style photography from its (tenuous) ideals of candidness. The photographs’ circulation via professional websites and media outlets has rendered the sartorial choices of fashion’s arbiters arguably more influential than collection photographs and has blurred distinctions between the fashions worn in the indoor and outdoor environments. Jennifer Craik describes a form of “global high fashion worn by fashion journalists, stylists, and celebrities who travel worldwide to attend fashion weeks and special fashion events” (354). It is this subset that cultural parlance terms street style. Ton’s aesthetic utilizes streetscapes to promote this internationalized mode of dress that communicates wearers’ status not just in fashion circles but as members of a larger cultured class. Cities function as status enhancers within a discursive system that privileges beautiful clothes and bodies. Elements that do reveal location, such as historical landmarks, function within existent cultural discourses to promote cities as idealized fashion capitals (or fashion cities) and tourist destinations (see Gilbert).[ii]

This article is part of broader research situated in fashion, media, and cultural studies: this research examines the mediation of the fashion show as a microcosm of online media’s effects on consumer culture and assesses the social discursive production of fashion shows and their attendees via diverse textual and visual platforms. It is crucial to contextualize Ton’s photographs as embedded within the academic and social histories of the discursive terms and practices that they appropriate. Furthermore, one must account for the production of cultural and aesthetic ideals specific to the cities in which these representations are located, including intersections with other aspirational branding and consumer practices, such as those of tourism.

I first outline the methods used to analyze Ton’s photographs and defines a theoretical conceptualization of Fashion Month as scene. I then document Ton’s rise to prominence within fashion’s industrial structures. Further, I describe how the mobilities of Fashion Month within dominant cities enact fashion’s condition of internationalization. Next, I offer a scholastic genealogy of street style to illustrate the class and racial tensions in which Ton’s discursive representations circulate. Further, I summarize research in street style photography as both photographic genre and material practice, contextualized within historical representations of modern cities and fashionable subjects. Ton’s photographs demonstrate—and are situated within—a persistent dialectic between “real” or “authentic” depictions and fashion’s editorial or commercial dictates: this dialectic reflects international cities’ contestations in the cultural positioning of urban environments and class-based and/or racialized constructs of the “street.”

Methods

I performed manual content analysis on a non-random sample of all of the photographs that Ton posted to Style.com during the Spring/Summer 2014 (n=339) and Fall/Winter 2014 (n=386) ready-to-wear women’s collections, for a total of 725 photographs (n=725). The breakdown of cities is as follows: Fall/Winter 2014—Paris (44.3%), New York City (27.7%), Milan (17.9%), London (10.4%); Spring/Summer 2014—Paris (47.8%), New York City (24.2%), Milan (16.5%), London (12.1%). To obtain an accurate count of cities depicted, I cross-referenced the photographs with the archives on Ton’s personal website, which names the locations.[iii] Paris photographs comprise almost half of the sample, suggesting that Ton either attended more fashion shows or preferred to take more photographs there; this statistic also attests to Paris’s dominance as a fashion capital (Rocamora).

Gillian Rose’s Foucauldian approach to visual discourse analysis intersects Ton’s photographs with related media discourses and aesthetic and embodied trends predicated on an elevated class echelon. Rose’s notion of social modality considers the “economic processes” and “social practices” that inform the production of visual materials (24-31). Central to reception is the element of compositionality, the presentation and relation of items (22). Agnès Rocamora’s formulation of fashion discourse, or fashion media discourse, combines Bourdieu’s symbolic value production and Foucault’s relation of discourses to institutional structures in order to read representations of Paris and other fashion capitals and of the persons that inhabit these cities.

The Fashion Month Scene

This article applies a Bourdieusian lens to the material and social structures of Fashion Month and to the consumer distinctions communicated in fashion show attendees’ sartorial choices. Joanne Entwistle and Agnès Rocamora, pace Bourdieu, describe Fashion Week as a literal manifestation of the field of fashion in which cultural intermediaries compete for cultural, social, and economic capital (736). This formulation parallels Will Straw’s characterization of scenes:

[A]s collectivities marked by some form of proximity; as spaces of assembly engaged in pulling together the varieties of cultural phenomena; as workplaces engaged . . . in the transformation of materials; as ethical worlds shaped by the working out or maintenance of behavioural protocols; as spaces of traversal and preservation through which cultural energies and practices pass at particular speeds, and as spaces of mediation . . . (477)

Fashion Weeks coalesce the industry’s social relations and material practices: audience risers create a Foucauldian “regime of looking”—a reverse Panopticon—in which members that possess the most influence are seated in the front row, visible to others (Entwistle and Rocamora 744). Insiders’ display of personal fashion capital constitutes a performance of habitus, sets of tastes and dispositions that Bourdieu identified as the product of class position (Entwistle and Rocamora 740). What can productively be called the fashion scene, or the Fashion Month scene, is rendered visible on an international scale and in an immediate timeframe via online photograph circulation. Bourdieu’s hierarchical theorization of consumer culture has its critics: Gilles Lipovetsky declared that the introduction of multiple markets facilitates individual choice, while Mike Featherstone posited that consumption in postmodern culture should be evaluated based on tastes. Subculture research, outlined below, further indicates alternative directions of fashion adoption. However the press’s increased focus on fashion show attendees indicates fashion’s reassertion of class-based hierarchies in the Internet era. Cultural intermediaries must appear to other field members, through their dress and embodiment, to possess appropriate economic capital, design knowledge, and professional connections (Entwistle and Rocamora 746). Consumers who access Fashion Month photographs perceive attendees as representative of an elite class, and their ability to travel to international fashion capitals as evidence of financial flexibility and industrial clout.

The Rise of Online Street Style Photography

Online street style photography became a recognized practice through the work of photographers such as Ton, Garance Doré (Garance Doré), Phil Oh (Street Peeper), Yvan Rodic (Facehunter), and Scott Schuman (The Sartorialist, who photographed for Style.com from 2006 to 2009). These photographers documented international street fashion, purporting to capture cities’ sartorial experimentation. Photographer and ethnographer Brent Luvaas contends that street style blogs’ “cultural value” resides in their illustration of “specific cities at specific moments in time … well beyond the traditional boundaries of the global fashion industry” (4). Print and online street fashion photographers have earned their reputations touring cities with a casual, all-seeing approach that scholars liken to the flaneur of the Parisian arcades. Fashion and visual culture scholars have written on Schuman and Rodic’s portraiture as demonstrative of the form. Popular claims of street style blogs’ democratic nature are predicated on online media’s geographical reach and interactive capacities (including comment forums); depictions of clothes from different price echelons; and the fact that bloggers earned professional notice through amateur practices. However, scholars problematize such utopian ideals, noting the promotion of a homogenous aesthetic that adheres to fashion’s limited embodied standards. Further, fashion’s stakeholders exerted an influence in the medium from its earliest incarnations via brand collaborations, advertisements, and invitations to practitioners to attend fashion shows.[iv]

Ton’s position as one of the earliest online street style photographers facilitated his rapid rise to influence in the field of fashion and the formation of an international forum for his work. Ton created his blog Jak & Jil in 2005 while working as a buyer at the luxury department store Holt Renfrew in Toronto (Amed). Canadian retailer Lynda Latner, impressed with Ton’s online work, paid for Ton to travel to Paris Fashion Week: there, Ton honed a “candid” and frenetic photographic style that differed from his peers’ portraiture (though he does shoot portraits) (qtd. in Amed). Still in his 20s, Ton was not as established in fashion as predecessors such as Schuman, who had worked in menswear (de Perthuis 4; Rosser 158). Nonetheless, his position at Holt Renfrew reinforces the fact that several street style visionaries already worked in fashion prior to starting their recreational online pursuits. In 2009, Ton was one of four bloggers invited to sit front-row at Dolce & Gabbana’s Spring/Summer 2010 presentation, a moment that scholars pinpoint as fashion’s consecration of the medium. That same year, Condé Nast hired Ton as its “resident” photographer of Fashion Month street style (replacing Schuman). During Ton’s tenure, the street style parade became a documented phenomenon. Nicole Phelps lists Ton’s recruitment as a catalytic event before street style exploded in the form of bloggers’ increased Fashion Month presence and the pervasive influence of brands and media sites on the practice. The seasons covered in the sample represent street style photographers’ dominance in the streets of Fashion Month, later to be outnumbered by press and commercial photographers (Luvaas 284).

Ton’s photographs for Style.com demand analysis, as those few scholars that have addressed his work situate him within street style photography but do not examine his oeuvre in detail. In 2011, The Business of Fashion deemed Ton “the world’s most influential street style fashion photographer today” (Amed, my emphasis). Luvaas cites Ton as a creator of street style stars (270). Other photographers observe whom he shoots, and his chosen intermediaries gain public recognition—Dello Russo, who appears 22 times in this sample (at least with her face discernible), is the foremost example (Titton, “Styling the Street” 132-33).[v] Furthermore, Ton’s aesthetic has become representative of street style photographs and is often used as a visual referent for the term itself. Style.com is not the sole outlet to publish Fashion Month photographs under a street style banner: however, it is (or was) an essential resource that contains news stories, product recommendations, and a comprehensive database of collection reviews and photographs.[vi] Announcing his departure, Ton praised the site as “the most influential and relevant fashion publication” (qtd. in Wolf). For such a reputable site to feature street style—documented during Fashion Month—represents fashion’s appropriation of online street style photography. The move did not just conflate street style with the outfits worn at Fashion Month but naturalized its direct, delimited association with intermediaries’ ensembles. In the site’s context, the street style photograph becomes solely a representation of Fashion Month and reads in relation to collection photographs and advertisements.[vii] Style.com does not invite reader comments but instead compiles a clickable album, a more commercial mode of presentation (see de Perthuis). Ton’s images thus communicates aesthetics from within Fashion Month as a scene to an online spectatorship. Karen de Perthuis notes that documentation of “how fashion works in [a specific] street style blog offers a model that can be translated or applied … to other types of blogs across the field” (4). Analysis of Ton’s Fashion Month street style photographs illuminates the medium’s enfoldment into established discourses.

Fashion on the “Street”

The presence of Fashion Weeks inform cities’ cultural positions, while their representations are situated within historical referents (Craik; Gilbert). Fashion capitals have become international due to increased corporatization of fashion houses and sponsorship of Fashion Week events—a phenomenon that Frédéric Godart terms imperialization (14, 129-42). Fashion Weeks impress a set of classist signifiers onto urban environments, through the arrival of editors, retailers, celebrities, and photographers and their enactments—what de Certeau terms spatial practices (96). Presentations occur in tourist-centered cosmopolitan areas rather than in residential (or disenfranchised) communities. Alan Blum examines scenes as products of cities’ “urban theatricality” and notes that “fashion scenes” are positioned as exclusive (365-67). Rocamora and Alistair O’Neill contrast “the public space of ordinary people” with “the exclusive space of the fashion show and its extraordinary audience of celebrities and other fashion insiders” (189). Fashion Month has assumed such spatial proportions, distinct ensembles, and theatrical interactions that columnists and scholars compare it to a circus or a red carpet affair (Menkes; Shea; Titton, “Styling the Street”). On-site observation that I conducted of New York Fashion Week in February 2016 confirmed a sartorial distinction between elite attendees and outsiders, the “real” inhabitants whose quotidian, work-related mobilities underwrite the streets (de Certeau 93). People familiar with Fashion Month photograph conventions can determine which individuals will attract photographers based on their outfits and attractiveness (see Luvaas 266). Nonetheless, comments from locals and tourists indicated that even outsiders could conclude that attendees’ dress transcended the mainstream. Craik stresses that event producers fabricate a “cosmopolitan atmosphere” via “international” associations (366): this construction follows tourism advertisements that turn cities into simulacral destinations (362). Notions of the international street as simultaneously accessible and elitist exist alongside alternative imaginings of the global street as a site of political resistance (Sassen). Fashion Month’s depictions of the urban street complement and clash with its often European associations to editorial effect: manipulating subversive formulations just as, pace de Certeau, the fashion scene performatively appropriates cities’ physical spaces (98).

Street Style in Discourse

Scholars trace the term street style to its references to popular trends and subcultural movements, situating its traditional associations in urban communities. Sophie Woodward defines street style as fashion worn and “observed on the street” and outlines how the term is constituted via a circuit of discourses: “as part of popular parlance, within media representations of fashion in the street style sections of magazines, in outfits that are assembled, in exhibitions and academics’ accounts” (84, my emphasis). Monica Titton delineates between notions of style, as individual experimentation, and fashion as subject to commercial imperatives (“Fashion in the City” 136). David Gilbert observes that communities influence cities’ cultural fabrics in a manner that fashion narratives overlook: “the creativity arising from the intermixing and chaos … the performance of fashion on the streets” (29). Research in subcultures illuminates problematics between examination of street style as representative of demarcated communities and acknowledgment of its diverse influences (Woodward 85). Caroline Evans observes that attempts to categorize subcultures overlook the nuances of cultural statements as derived from multiple sites, references, and practices.[viii] Subcultures have offered well-documented inspiration to fashion: hip-hop and punk aesthetics have recurred in the collections of Chanel and Jean Paul Gaultier and in mainstream retail lines (Barnard 45-46). Ted Polhemus formulates a “bubble-up” model of influence that contradicts classical social theories. Dick Hebdige asserts that the dominant culture incorporates statements’ subversive intent for commercial and political interests (94). For publications to name Fashion Month photographs street style represents not just an incorporation of the medium but also fashion’s textual incorporation of the term. In limiting street style as a referent to Fashion Month ensembles, the press erases dress as a situated practice and describes items from high fashion, positioned at a socioeconomic remove from urban communities. Journalists complain that for media discourses to use the term to refer to intermediaries’ outfits diminishes the individual locatable expression that true street style should constitute, and lament a lost space “free from” fashion’s “transactional compromises” (Berlinger; see also LaFerla, Shea). Indeed, editors’ outfits are often donated or loaned from fashion houses and public relations companies, and high-profile attendees have become notorious for changing outfits between presentations.

Street Style in Photographs

The historical presence of cities and streets, as place and idea, illuminates how fashion photography operates on a spectrum between the authentic and the produced, invoking a contentious politics of urban representation. Fashion needs “the street” to position itself as upper-class, while the “street” needs fashion to read as authentic (Rocamora and O’Neill 189). In an echo of Woodward, Luvaas defines street style photography “as simply fashion photography taken ‘on the street,’” in contrast with studio shoots and fashion shows (23, my emphasis). Predecessors include street photography; anthropological portraits; fashion photographs of models in outdoor locations or studio-replicated streets; street style photographs in which subjects are not aware of the camera; and portraits of non-professional subjects (see Luvaas).[ix] Titton comments that cities have occupied a “central” position “as both scene and real space for the photographic staging of fashion” (“Fashion in the City” 128). Luvaas and Titton (“Styling the Street”) trace street style photographs to the modern period and its fascination with man-made environments, notably Haussmann’s Paris. Luvaas articulates the predominance of “the street” as “a subject of street style photography, perhaps even the subject, a fluid, amorphous entity that accumulates meanings as it snowballs into fashion world ubiquity” (25, original emphasis). Fashion photographers such as Irving Penn and Edward Steichen romanticized the street as a construct of urban impoverishment: a location “where upmarket fashionistas could go slumming in search of ‘real life’” (Luvaas 43; see also Rocamora & O’Neill 187). Fashion’s embrace of subcultures and countercultures celebrated the street as a site of raw expression (Luvaas 44; Rocamora & O’Neill 188-89). The work of print media street fashion photographers such as Bill Cunningham and Amy Arbus in New York demonstrates a confluence of these aesthetics (Luvaas 45-47; Titton, “Styling the Street” 128-29).[x] iD Magazine’s iconic 1980s “straight-up” portrait showcased the UK’s “real” fashion choices via its comparative lack of production. Subjects were captured against a white wall on an actual street, represented as a “site for the creative performance of ‘real’ people” (Rocamora & O’Neill 185; see also Luvaas 49). Creator Steve Johnston shot most of the portraits in front of the same wall—the location was both specific and representational (Luvaas 51). Rocamora and O’Neill contend that print media’s co-optation of street fashion erased the street in lieu of a metaphorical (and perhaps racist) white space or brick wall: i-D’s 2003 studio-produced homage to street fashion renders the street “a blank canvas” or a reductionist “urban wasteland” (195). The Los Angeles magazine NYLON and the Japanese magazines FRUiTS and TUNE return to a more untouched street fashion portraiture (Luvaas 55-56).

While online street style photography returns to literal streets, it commits a similar act of erasure—the wall reappears, but its connotations are editorialized. Luvaas posits that the street has been turned into a “conceptual screen” (25), blurring social and locational contexts. Susan Ingram observes that The Sartorialist renders cities visually indiscernible:

[T]he city forms an anonymous backdrop against which fashionistas can look urban. The [subjects] … are in an interesting way placeless. In many of the images, the city disappears completely, and it is rarely clear from the photos themselves where they have been taken, which is why each has to be labeled. Viewed without their labels, it becomes apparent how lacking in specificity these places are, and how similar the looks. (188)

Elizabeth Wilson notes that marketers use the term “urban” to invoke the lifeblood of streets or allude to wastelands (35): these inverted associations become connected to cosmopolitanism. Sarah Banet-Weiser asserts that “street” and “urban” are racialized in American cultural discourses, connoting dangerous ghettos or nostalgic historical sites (105). For Luvaas, the street remains contested: “the last vestige of authenticity in a commodified culture and … a stage on which that very commodified culture performs some of its most ostentatious displays” (68). Ton’s photographs collapse the distinction between the authentic and the constructed, imposing the fashion scene upon the “street” and repositioning the street itself as status marker.

Ton’s photographs must be read beside his contemporaries’ ambivalent realizations of the “street.” Luvaas likens Ton’s aesthetic to that of H. B. Nam (streetfsn.com), Youngjun Koo (koo.im), Michael Dumler (onabbottkinney.com), Nabile Quenum (jaiperdumavest.com), Driely S. (Driely S.), and Adam Katz Sinding (Le 21ème) (63-64). These photographers’ movement-based shots include “the details of the garment” as but one component and instead reconstitute the modernist, European street “of the poetic moment … of romantic possibility, of happy accident … [the rest] dissolves into a field of lens blur” (Luvaas 65). Ton remains, however, a pioneer in the use of the horizontal frame and cropped focus (see Phelps). While lens blur and streetscapes are prominent compositional elements, Ton’s conceptualization of the street is much more complex: here, it becomes aestheticized and often effaced. Moreover, his focus on fashion is far from (and cannot be) incidental. Ton’s is the international street of fashion tourism, of tourist mobilities predicated on consumerism, and the arrival of the international fashion set (Craik 354). Ton’s composition is more readable than that of his peers, prioritizing opulent commodities and their aspirational wearers over mood. However, the photographs are not democratic: rather, the aesthetic treads a line between the experimental and the commercial.

Analysis: Tommy Ton’s Cities as Streetscapes

Ton’s photographs share numerous elements: foremost are the attendees walking or running to or from venues, while in the background are rows of town cars, taxis, and motorbikes and/or textured architecture. Ton also offers cropped torso shots or close-ups of handbags, shoes, and other accessories (Fig. 2). Ton positions the street as an editorial backdrop against which to emphasize fashion; cities are often recognizable only to those who are already familiar with them. Weather helps to indicate location: shifts inform light and shadow, while select photographs represent extreme conditions. New York endured wet snowfall during Fall/Winter 2014 Fashion Week, and several photographs depict insiders protecting themselves from the elements. Taxis and buses, in addition to license plates, often become the only markers of place. Sixteen photographs taken at New York Fashion Week (eight from each album) show editors in front of iconic yellow taxis; similarly, red double-decker buses feature in several London photographs. Nonetheless, the vehicles’ presence becomes naturalized as a scene of international mobilities and an advertisement for these cities as tourist destinations: not cities as lived but cities as discursively produced. The vehicles become a flattened and often blurred element. More than half of the photographs (56.1%) make visible the literal street and its referents (54.7% for Spring/Summer 2014 and 57.3% for Fall/Winter 2014). 349 photographs (48.1%) illustrate cars; 104 (29.8%) of these feature cars in a prominent position. 211 photographs (29.1%) contain traffic, parking, or directional signage, or barriers and traffic cones. 219 photographs (30.2%) depict subjects on or in the street, while 69 (31.5%) of these show an indicated crosswalk (Fig. 3). 174 photographs (24.0%) capture individuals close in front of an architectural structure, while half (50.1%) illustrate architectural structures in the distance. 33 photographs (5.0%) were coded as “perspective shots” that Ton took from the middle of a street, creating a striking aesthetic that recalls a modern-era fascination with urban architecture (Fig. 4).

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

Ton’s photographs frequently convey a sense of placelessness, similar to those of The Sartorialist. Esther Rosser observes that photographs’ location in the dominant fashion capitals lends clout to the insiders who appear (161; see also Titton, “Styling the Street” 132). However, status is communicated through the fact of the subjects’ location and not the cities’ specific architectural features. I coded 343 photographs (47.2%) as “streetscape,” in which elements of the urban setting comprised significant additional space in the frame or were otherwise instrumental to the composition (Fig. 5). This percentage is consistent across seasons (51.3% for Spring/Summer 2014 and 43.8% for Fall/Winter 2014). Historical architecture with friezes and columns reads as European but not location-specific: it increases the cachet of the locations as museum cities. It suffices that the architecture appears to be antiquated and European. 76 photographs (10.5%) capture subjects in front of walls or doors, whose colours and textures reflect or contrast with their outfits (11.5% for Spring/Summer 2014 and 10.0% for Fall/Winter 2014). 20 of these photographs (26.3%) feature a brick wall. One particular beige brick wall in New York (Fall/Winter 2014) matches an insider’s parka (Fig. 6). In a subsequent photograph, it offers a plain canvas to foreground Russian fashion editor Miroslava Duma’s flower-printed coat (Fig. 7). 404 photographs (55.7%) use lens blur to render streets indiscernible or erase them (53.1% for Spring/Summer 2014 and 58.0% for Fall/Winter 2014). 129 photographs (17.8%) contain sculptures, walls, architectural structures, landmarks, or (torn) street posters or advertisements that bear similar or opposite colour palettes and/or textures to subjects’ outfits.

In 18 photographs (9 from each album), from New York and Milan, Ton juxtaposes ensembles with graffiti. Banet-Weiser examines street art’s “ambivalent” role, both contentious and productive, in cities’ cultural positioning: “street art’s association with graffiti and tagging … are not only deeply racialized in the US imagination but also fetishized for their links to racial otherness” (101). Graffiti emerged out of the 1970s and 1980s US hip-hop scene in response to the encroachment of commercial culture onto public spaces and the disenfranchisement of Black and Latino neighbourhoods under New York’s “urban ‘renewal’” policies (Banet-Weiser 102). As “figures” that rhetoricize urban spaces, such “calligraphies howl without raising their voices” and resist photographic pinning down (de Certeau 102). Cities’ use of street art to self-brand as creative—making it palatable for a white audience (Banet-Weiser 105)—parallels photographers’ use of graffiti to mark streets and persons as fashionable. In a Fall/Winter 2014 Milan photograph, Ton frames Dello Russo in profile in a fringed black jacket and pencil skirt in front of black, curled scrawl (Fig. 8). In another, a woman stands in a white trench coat (printed with red lips) and embellished red heels in front of a yellow wall with red graffiti (Fig. 9). The tagged walls invoke “urban” hip-hop aesthetics to create a class contrast that prioritizes the expensive fashions.

Figure 5

#gallery-0-7 { margin: auto; } #gallery-0-7 .gallery-item { float: left; margin-top: 10px; text-align: center; width: 50%; } #gallery-0-7 img { border: 2px solid #cfcfcf; } #gallery-0-7 .gallery-caption { margin-left: 0; } /* see gallery_shortcode() in wp-includes/media.php */

Figure 6

Figure 7

Figure 8

Figure 9

Tourist Locations

Ton has begun to depict specific locations more often, as certain fashion shows are held at recognizable tourist destinations; however, he continues to use attractions to construct a fashionable aesthetic. Rocamora recalls that the Eiffel Tower is Paris’s most persistent visual signifier, functioning, like a couture label, as a “geographical signature” (172). Artists depict the Tower as a feminine form, as the shape of its base recalls the lines of a dress or skirt (167). Three photographs juxtapose the Eiffel Tower with female fashion personnel. In the first, Dello Russo stands in black stiletto boots and a black mini-dress. Lean and muscular, she appears half as tall as the structure, while the chainmail pattern on her dress echoes its crossed steel beams (Fig. 10). In the second, editor Giovanna Engelbert stands cross-legged, wearing a sweater dress that flares out past the knee and black stiletto heels (Fig. 11). In the third, stylist Sarah Chavez stands in profile, bent over to light a cigarette; her ankle-length skirt blows in the wind (Fig. 12). Ton comments that “there’s a certain chicness to the way that people smoke” (qtd. in Hainey). The Eiffel Tower creates a sense of placelessness, as the view from the top “naturalizes” Paris within the modern period as simulacrum (Rocamora 166), in a similar manner to de Certeau’s view from New York’s World Trade Center (92-3). Craik declares that the “traveling … spectacle” of Fashion Month “rivals the more familiar attractions of the tourism industry” (368). In one Paris photograph, editor Michelle Elie performs an air kick that frames a group of tourists and their guide (recognizable for his flag) (Fig. 13). Ton’s photographs therefore reduce landmarks to icons for international tourism and invoke their associations as a thematic, luxurious backdrop.

#gallery-0-8 { margin: auto; } #gallery-0-8 .gallery-item { float: left; margin-top: 10px; text-align: center; width: 33%; } #gallery-0-8 img { border: 2px solid #cfcfcf; } #gallery-0-8 .gallery-caption { margin-left: 0; } /* see gallery_shortcode() in wp-includes/media.php */

Figure 10

Figure 11

Figure 12

Figure 13

Fashionable Mobilities as Exclusive

The photographs’ composition presents fashion as an exclusive realm in which access is denied via subjects’ visualities and positionalities. Just 84 photographs (11.6%) depict subjects that look at the camera: all others look ahead or to the street, are shot from behind, or have their heads omitted from the frame. 199 photographs (27.5%) illustrate subjects wearing sunglasses. 258 photographs (35.6%) feature subjects holding a cell phone, while 94 (36.4% of these) illustrate subjects talking or texting, detached from the chaos or coordinating their schedules. Ton claims that insiders’ nonchalance attracts his lens: “the fact that they don’t want to be photographed or they’re running away from you makes you want to photograph them more” (qtd. in Hainey).[xi] Attendees maintain an awareness of Ton’s surveillance, as he has the power to render them visible outside of the field of fashion. While the totality of photographs depicts the “fashion set” as a collective, Ton’s selective focus on specific members indicates that the competition for distinction happens at an individual level. 83.6% of the photographs (606) feature one individual (even if others appear in the background) while none features more than five. The rest of the scene becomes enfolded into the spectacle: 261 photographs (36.0%) feature members in behind, near or at a distance (38.1% in Spring/Summer 2014 and 34.2% in Fall/Winter 2014), while a handful (45, or 6% of total) capture other photographers shooting the same subjects, boosting their visible social influence.

The sense of exclusion is enhanced via icons and invocations of urban mobilities: recalling de Certeau, the scene is constituted via the modalities of walking (99). Directional signage appears with arrows pointing to other parts of cities (Fig. 14). Traffic markers indicate “walk” or “don’t park,” preventing persons from becoming situated. Street names function as “metaphors … detached from actual places … a foggy geography of ‘meanings’ held in suspension, directing the physical deambulations below” (de Certeau 104). Here, street names indicate everywhere and elsewhere. 401 photographs (55.3%) depict subjects walking, often with their skirts, coats, or hair billowing behind them or in the opposite direction. 430 photographs (59.3%) are shot at a 45-degree angle. 219 (30.2%) position subjects at the side of the frame to showcase the streetscape or the crowd as additional elements. 101 (13.9%) depict subjects in profile. 84 (11.6%) tilt subjects’ bodies. The bodies’ ephemeral presence in the frame invokes Peggy Phelan’s famous observation that the disappearance of the female form as unmarked is powerful, just as performance’s disappearance informs its cultural status. 149 photographs (20.5%) communicate an overall sense of movement due to the curvature of a sidewalk or traffic circle; to the position of vehicles in extreme close-up, or parallel or opposite to the subject’s facing direction (Fig. 15); or to subjects depicted riding bicycles or motorbikes. That Ton photographs hundreds of these movements emblematizes de Certeau’s observation of mobilities as individual and fragmented: “The moving about that the city multiplies and concentrates makes the city itself an immense social experience of lacking a place … broken up into countless tiny deportations (displacements and walks)” (103). For the duration of Fashion Month, personnel (several of whom work in international markets) become placeless, as do their ensembles. Attendees often do not inhabit these cities outside of the hectic presentation schedules (Craik 367; Skov 773). Ton’s photographs, however, position these insiders as arbiters of “real” fashion: street names are immaterial—rather, fashion is constructed as an aspirational realm within its international cities.

Figure 14

Figure 15

Embodied Fashion Capital

The fashions and bodies that appear in Ton’s frame reference high fashion’s ideals of embodied social distinction. Bourdieu observed that the upper classes base consumer choices on considerations of cleanliness, smoothness, and fabrics to convey financial ease (Distinction 247-48). Fashion insiders here similarly communicate a moneyed aesthetic through luxurious fabrics. Outerwear appears in 504 (69.5%) photographs—166 (49.0%) from Spring/Summer 2014 and 338 (87.6%) from Fall/Winter 2014. A total of 598 pieces are depicted, due to multiple people in the frame or to layering practices.[xii] 239 coats (40.0%) appear to be constructed from wool or felt; 126 (21.1%) appear to be leather or suede (often the classic black leather jacket); and 80 (13.4%) read as fur, faux fur, or (in two cases) feathers. Dana Thomas states that such materials have functioned as signifiers of privilege since prehistoric times (6), and that leather handbags continue to be fashion’s most coveted item (188-194). Identifiable brand logos do not consistently appear, though Louis Vuitton’s “Damier check canvas” pattern and Chanel’s quilted leather are still visible on handbags (see Thomas 19). 492 photographs (67.9%) contain handbags or purses. 564 handbags appear in total, while 60 photographs contain more than one item: handbags are the focus of 148 (30.1%) of these photographs. 405 bags (71.8%) appear to be made of leather, crocodile, suede, or other animal skins, while 163 (40.2%) are black leather. Journalist Connie Wang muses that, because insiders’ ensembles’ worth resides in fabric and construction, provenance is discernible only to members: “The people who know about these things know that the plain grey sweater is from The Row and costs $1,000” (qtd. in Shea). Authentic field membership is thus indicated through authentic materials, which denote authentic luxury brands to those that possess authentic fashion capital.

Ton’s photographs further promote pervasive industrial standards of attractiveness that are both classist and racialized. Titton comments that street style blogs “reintroduced the body image, racial stereotypes, and sartorial style of mainstream fashion into a new media format and an old photographic genre” (“Styling the Street” 135). 98.0% (711) of the bodies in Ton’s photographs were coded as “lean,” “lean–athletic,” or “lean–petite,” while another 13 (1.8%) were coded as “petite.” Half (50.0%) of all outerwear pieces were coded as “oversized”: the exaggerated proportions serve the simultaneous function of rendering the clothes distinctive and the wearers’ bodies slimmer.[xiii] 34 coat-wearing individuals (20.6%) in Spring/Summer 2014 and 50 individuals (14.8%) in Fall/Winter 2014 drape coats over their shoulders, emphasizing a lithe frame underneath. Titton claims that the repeated appearances of editors such as Giovanna Engelbert and Hanneli Mustaparta, who both had prior modeling careers, illustrate street style blogs’ aesthetic reductionism (“Styling the Street” 135). Engelbert appears fourteen times in the sample, and Mustaparta four times; other editors such as Emmanuelle Alt (five appearances) and Caroline de Maigret (eight appearances) also worked as models. Ton also features current models: blonde Belgian model Hanne Gaby Odiele appears in thirteen photographs (third behind Dello Russo and Engelbert). East Asian models Ming Xi, Liu Wen, Soo Joo Park, and Xiao Wen Ju appear 29 times combined. Other faces-of-the-moment include Joan Smalls, Saskia de Brauw, Caroline Brasch Nielsen, Binx Walton, Edie Campbell, Chloe Norgaard, Alanna Zimmer, and Grace Mahary, all photographed three or more times. The racial breakdown reflects fashion’s disproportionate whiteness: Caucasian—502 (69.3%); East Asian—95 (13.1%); Unclear—91 (12.6%); Black—34 (5.0%).[xiv]

Elements of “Real” Streets

Elements of the “real” streets persist that resist incorporation, such as construction sites or refuse; however, Ton contains these within an aesthetic frame. In Fall/Winter 2014, Ton captures Torontonian bloggers and socialites Samantha and Caillianne Beckerman—profiled for their eclectic, expensive tastes (Sanati)—at New York Fashion Week, posing alongside street workers (Fig. 16). The photograph illuminates the labour that maintains cities, but also smacks of class tokenism. One of the twins dons a worker’s vest and a neon toque, making her resemble a traffic cone, while holes in her sweater and jeans suggest burns or contact with the pavement. Jeans appear in 175 photographs (24.1%), often ripped or with oversized patches. Calculated distressing increases their retail value and creates an appearance of conspicuous waste. In contrast, the workers’ uniforms are intact and clean. Three street workers are black, while the Beckerman twins represent the white subjects that dominate Ton’s photographs. Luvaas observes street style photographs’ capacities to render “occasional critique” of the class-based nature of Fashion Month’s social enactments (64). However, the posed, even touristic appearance of this photograph eliminates such potential. The combination of high fashion and street workers’ uniforms abstracts street fashion from situated streets and occludes the cultural specificities of fashion capitals, in addition to the high-low sartorial combinations that once characterized notions of street style.

Figure 16

Conclusion

Analysis of Tommy Ton’s Style.com Spring/Summer 2014 and Fall/Winter 2014 photograph albums demonstrates that high fashion has incorporated the contested term street style to refer to the ensembles worn by members of the elite industrial scene within fashion cities. Scholars and columnists propose that fashion editors have become the primary arbiters of trends, perhaps more so than the collections. Titton documents a reciprocal relationship between intermediaries who have advanced their careers via appearances in street style photographs and behind-the-scenes tastemakers and decision-making processes that dictate what is fashionable (“Styling the Street” 135). Editors are trusted to “incorporate the newest fashion trends into their wardrobes” because their positions place them ahead of a representational curve (135). However, close examination and season-to-season comparison of Ton’s photographs reveals that ensembles are uniform: a flattened mode of dress via which members of the fashion set communicate industrial and social distinction, rather than a mode of innovative, individual expression. Furthermore, editors who wear items direct from the runways disseminate trends determined by fashion houses (Berlinger), but do not demonstrate that these trends can be made wearable. Titton declares that “the establishment of street style blogs was only possible through the intense cooperation with fashion industry insiders and resulted in the reinforcement of prevailing power structures and visual narratives” (“Styling the Street” 135). Ton’s Style.com albums can be seen as evidence of this collusion. However, the photographs’ aesthetic standards are not those of mainstream fashion but rather those enclosed within the field of fashion, a (materialized) realm predicated on class-based forms of capital. Style.com, while accessible to consumers thanks to the ostensibly democratic medium of the Internet, is nonetheless dedicated to high fashion aesthetics. The comprehension required to read the photographs is predicated on habitus: if one recognizes a specific location, architectural element, or designer, one feels a sense of inclusion within an elite and mobile fashion scene. At the same time, it becomes sufficient to represent these cities as fashion capitals rather than as specific geographical locations. Since not all consumers possess the means to travel or to purchase the products or the clout to attend fashion shows, street style photographs become a tool for the production of desire. The proliferation of these images as representative of the “real” is intended to fuel the luxury and mainstream marketplaces via consumers’ imitation. Further critical analysis of Fashion Month representations should account for consumers’ social interactions with fashion content, and their material effects, in the Internet era.

Works Cited

Amed, Imran. “The Business of Blogging | Tommy Ton.” The Business of Fashion 28 Mar. 2011. Web. 23 Oct. 2016.

Banet-Weiser, Sarah. Authentic™: The Politics of Ambivalence in a Brand Culture. New York and London: New York UP, 2012. Print.

Barnard, Malcolm. Fashion as Communication. 2nd ed. London and New York: Routledge, 2002. Print.

Berlinger, Max. “Op-Ed | What happened to street style?” The Business of Fashion 23 Jan. 2014. Web. 23 Oct. 2016.

Berry, Jess. “Flâneurs of Fashion 2.0.” Scan Journal 7.2 (2010). Web. 23 Oct. 2016.

Blum, Alan. The Imaginative Structure of the City. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s UP, 2003. Print.