#scrubland mammals

Text

Close Up with Coyotes

Often confused with wolves, foxes, or even stray dogs, the coyote (Canis latrans) is a species of canid found only in Central and North America, from Panama to central Canada. Historically, the coyote mainly occupied grasslands, scrubland, and deserts; however, in the past few centuries the species has expanded its range to include deciduous and evergreen forests, mountains, swamps, and even cities. Generally individuals and groups keep to one home territory, but they will move when resources become lacking.

Among the canines, coyotes are rather small, weighing only 8 to 20 kg (18 to 44 lb), and males tend to be larger than females. Generally coyotes sport a light gray, red, or brownish coat with a lighter underside; however, regional populations may differ wildly. This species may be identified from other canids by its large pointed ears, whitish facial markings, and narrow snout.

Though C. latrans does occasionally form packs, it is more likely to hunt individually or in small family groups. Nonfamily packs, usually made of bachelors, are rare. In addition, coyotes have been known to form mutualistic hunting relationships with other species like badgers. It is primarily carnivorous, hunting mainly at dawn and dusk for rabbits and hares, squirrels, mice, lizards, and occasionally larger targets such as deer or pronghorn. This species will also readily consume carrion, as well as produce and human food waste, making it highly adaptable to urban areas. Traditionally, the species has been limited via both competition and direct predation by wolves and cougars; in its expanded range, coyotes may also be predated upon by bears, alligators, lynx, and golden eagles.

Though reproduction typically takes place in the spring, from January to March, temporary pair bonds may form as early as November. Mates prepare dens, which may be dug out or selected from tree hollows or pre-existing burrows, and establishes a territory up to 19 square km (11 square miles). During this time, daughters from a females previous litter, or her sisters, may join the group. Pregnancy typically lasts just over 60 days, during which time the male and any assisting females do most of the hunting. Litters average 6 pups, and weaning takes about a month. During this time, the male continues to provide for the mother and pups, but will abandon the den if the mother goes missing. By the age of four or five weeks the pups develop a hierarchy through play-fighting. After about 6 months, the male pups will leave, while females will typically stay with their mothers until at least the next mating season, at which time they reach sexual maturity. In the wild, individuals may live as long as 10 years.

Conservation status: Due to its large range and adaptability to human habitats, the C. latrans is considered Least Concern by the IUCN. In urban areas, coyotes are regularly hunted as a nuisance species due to their predation on free-roaming pets and, occasionally, livestock.

In traditional Indigenous American stories, the coyote was seen as a trickster or anti-hero (here is an interesting paper about the 'Coyote' character in traditional stories versus western interpretations). The European colonization of North America and the eradication of large predators like wolves and cougars has allowed coyotes to spread far beyond their original geographic range and become a 'nuisance species' in urban areas.

If you like what I do, consider leaving a tip or buying me a ko-fi!

Photos

Neil Nurmi

Carlos Porrata

Natrice Miller

Tom Koerner

#coyote#Carnivora#Canidae#canines#canids#carnivores#mammals#generalist fauna#generalist mammals#grasslands#grassland mammals#scrubland#scrubland mammals#deserts#desert mammals#north america

169 notes

·

View notes

Text

November 10, 2023 - Steppe Eagle (Aquila nipalensis)

These booted eagles breed in open steppe and semi-desert scrubland across much of central Asia, and winter in parts of southern Asia, the Middle East, and eastern and southern Africa. They hunt small mammals, as well as birds, reptiles, and insects. Breeding from April to June, they build large platform nests from sticks lined with twigs, feathers, and other materials. In Mongolia some nests are constructed almost entirely of bones. Pairs usually nest on the ground but recent habitat changes have led to more nests being built on trees, bushes, and other elevated locations. They are classified as Endangered by the IUCN due primarily to habitat loss caused by agriculture and are also at risk from frequent collisions with power lines.

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fairy Dormouse, 2024

My first artwork of the new year! A cute lil fairy inspired by the hazel dormouse, a tiny mammal that resides in the woodland, scrubland and hedgerows of the UK.

Rodents forever <3 <3

#embroidery#fairycore#cottagecore#kitsch#queer artist#hand embroidery#illustration#naturecore#uk wildlife#uk nature#wildlife#dormouse#cute mouse#mice#original art#art tag#art#embroidery hoop#embroideryhannah#animal embroidery

15 notes

·

View notes

Note

I see where this is going now. Guess I'll try to think of whatever other hamster lineages in the Middle Temperocene that either aren't as common as they once were back in the Therocene/Glaciocene, reduced to one (or few) species, some small and insignificant ones that live on the mainlands but become bigger and more specialized on isolated islands, and/or haven't been brought up yet, etc. What about that Pangolin like Hameleon from Gestaltia that you mentioned plenty of times?

The hameleons are a group of early, basal rattiles that adapted to an insectivorous diet in a life up in the treetops. Equipped with grasping feet, long tongues, and hook-like scales on their tails, the hameleons were fairly successful in the Glaciocene but would dwindle in the end-Glaciocene mass extinction. The clade would be survived by bigger, hardier forms in Gestaltia's tropics, however, and in the Middle Temperocene the hameleons are not very diverse, but thriving in the few species they do have.

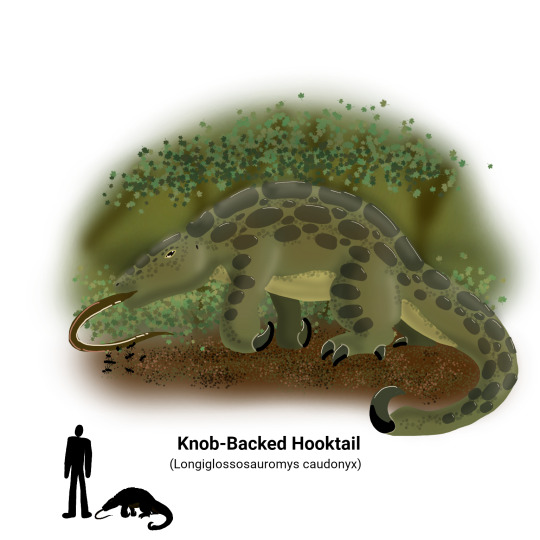

Knob-backed hooktails (Longiglossosauromys caudonyx), growing to over six feet in length, are the largest and most abundant and widespread of the extant species, being found across forests, grasslands, scrubland, hills, coasts and savannahs across Gestaltia's tropics. Anywhere warm and wet enough for insects to thrive is an ideal home for the hooktail, with digging claws, a long snout, a long sticky tongue and a complete lack of dentition characteristic of various myrmecophages. Lacking teeth entirely, the hooktail grinds its insect prey using minute spines on its tongue and palate.

Hooktails live primarily on the ground, but, still possessing the gripping toes and hooked tail of their arboreal ancestors, are fairly skilled climbers as well, scaling dead, dried-out trees to access termite nests breeding within. Slow-moving and never in a hurry, hooktails use their armor plates to good use to defend themselves from predators such as badgebears and pterodents, curling their head inwards to their chest and exposing their tough, hard backs to the claws and teeth of their would-be attackers.

Hooktails, perhaps surprisingly, are one of the few rattiles to have re-evolved parental care: long after their ancestors birthed numerous independent young able to fend for themselves and thus did away with the mammals' primary innovation: mammary glands that secrete milk. Yet this has opened up unusual new styles of care in the rattile lineages that re-evolved it, specifically ones centered on the male: hooktails pair up for the breeding season, with the male regurgitating food for the female during the duration of her gestation. Once she gives birth, to a litter of about a dozen young, she departs soon after: and the parental care now falls upon duty for the male.

The youngsters ride on the male's back for several weeks, being carried around and fed regurgitated food until they are too large for their father to carry around. Even after, they continue to follow him around as he leads them, mostly passively, toward food and away from danger, and at about two years of age they are nearly their adult size and thus gradually, and one-by-one, disperse from their parent's territory to seek out their own independent lives.

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

Who is the supreme little guy?

Ferruginous pygmy owls are very small, about the size of a bluebird. They live in a variety of habitats from the southwestern US through Central and South America. They mostly prey on insects, but also eat small mammals, birds, and lizards. They have false eye spots called ocelli on the backs of their heads to deter predators. Like many other owls, parents continue to care for their young for several months after fledging.

Elf owls are the smallest owls in the world, about the size of a sparrow, with a wingspan of about 27 cm (10.5 in) and weighing about 40 g (1.4 oz). They live in deserts, dry scrublands, and open forests from the southwestern US through Mexico. They mostly feed on arthropods such as beetles, moths, crickets, and scorpions. They nest in cavities in saguaro cacti abandoned by woodpeckers.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

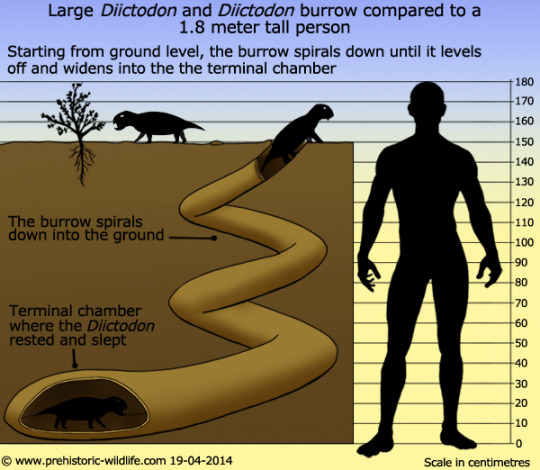

Diictodon is an extinct genus of pylaecephalid dicynodont, a lineage of mammal-like synapsids lived during the Late Permian period, approximately 255 million years ago. Fossils have been found in the Madumabisa Mudstone of the Luangwa Basin in Zambia, the Teekloof Formation, Abrahamskraal Formation, Balfour Formation, and Middleton Formation of South Africa and the Guodikeng Formation of China. Measuring around 12 to 15 inches in length and weighing between 1 and 3 pounds, Diictodon sported a short round body, stubby legs, sharp claws on the front feet, and a small yet strong beak. Like other dicynodonts, it possessed a pair of large tusks that erupted and pointed down from the upper jaw. In life Diictodon would have lived in arid scrubland around water sources such as rivers, oasis, and flood plains. They would have most likely been a primarily nocturnal animal, spending the night socializing and feeding upon the roots, leaves, and seeds of various desert shrubs and bushes while escaping the harsh heat of the arid days by burrowing. Diictodon burrows typically spiral down up to 6ft into the ground before leveling off into the terminal chamber where pairs of Diictodon would have slept and reared young. Although Diictodon did not build interconnecting burrows with others of its species, evidence suggests that large numbers would gather and burrow in close proximity to one another in a fashion similar to modern gofers. This unique adaptations and life style allowed diictodon to be one of the most successful synapsids throughout the Permian period.

Art seen above belongs to the following creators:

Emily Stepp: https://twitter.com/Emily_Art/status/1312088542152024064

Julio Lacerda: https://252mya.com/products/diictodon-burrow-stock-photo

Johannes VIII: https://johannesviii.tumblr.com/post/639068061132095488/diictodon-who-survived-the-most-brutal-extinction

http://www.prehistoric-wildlife.com/species/d/diictodon.html

#pleistocene pride#pliestocene pride#paleozoic#permian#extinct#synapsid#diictodon#dicynodont#just a little guy

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Creature Files: Jackalope

Place of Origin: United States

Habitat: Desert scrubland, sand dunes, prairies, and woodlands

Class: Mammal

Threat Level: XXX (Moderate)

Next to Bigfoot, The Loch Ness Monster, and the Mothman, the Jackalope is one of the most well-known (and most misunderstood) Cryptids.Technically speaking, the Jackalope isn't really a cryptid but rather a “Fearsome Critter” but neither here nor there. Jackalopes can be found all over the States, mainly in Wyoming and neighboring states, but also in Minnesota and Wisconsin.

Jackalopes bear a striking resemblance to the common jackrabbit, with the exception of their distinctive antlers which grow during the breeding season. Most idiots online will tell you that Jackalopes are simply rabbits suffering from the Shope Papilloma virus, but I assure you that Jackalopes, like all mythical creatures, are very real. Unlike rabbits, Jackalopes are highly territorial and will attempt to gore would-be predators with their antlers. That is why it is important to wear protective gear when encountering one.

Another easily discernible trait possessed by the Jackalope would be its distinctive call. The Jackalope will often mimic the sounds of other creatures and incorporate them into its mating call. They specifically prefer deep sounds so they would often mimic the campfire songs of cowboys and ranchers.

Jackalopes are specialized herbivores, and subsist entirely off rotting cactus. Jackalopes are fond of its mild, alcoholic flavor and so whiskey is often used as bait by jackalope hunters. Around the beginning of the 20th century, people started catching female Jackalopes, as their milk supposedly had healing properties. This excessive hunting caused the Jackalopes numbers to dwindle. Nowadays, the Jackalope is a very rare sight. May the Jackalope continue to inspire and amaze.

67 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lemuria: The Dreaded Titicula

Young Titicula emerging from an elephant wound. By Dave Garcia.

The island of Lemuria is home to a staggering mammalian megafauna, ruled over by large birds of prey. Yet, few creatures inspire as much fear in the prey mammals – including human beings – than the Titicula, Drepanorhamphus sarcokatastrofeas.

About the size of a sparrow, the Titicula is a very odd bird. A lemurornithid – a flying paleognath related to elephant birds and kiwis – it bears the hallmarks of this clade’s weirdness: pamprodactyl fuzzy feet, puffy degenerate hindwings, no tail feathers. It also has some weird traits of its own; alongside flamingos it is the only vertebrate in which the rictus extends past the orbit, almost reaching the nares in a fleshy “cheek”, in its case housing glands that produce a strong antiseptic, the birds licking over wounds in order to prevent infection and allow cellular regeneration. Males tend to be slightly larger than females and have black bands on their shoulders, but both sexes are generally not very dimorphic, both possessing a primarily brown spotted plummage with a white underside. They do, however, diverge in the beak.

Native to western Lemuria, the Titicula’s range extends across savannahs, scrubland, semi-desert and open forest biomes, reaching all the way to montane grassland mosaics. It is a mostly nomadic animal, though some montane populations are migratory, wintering in the lowlands. Bearing a long, slender beak, the Titicula is mostly a terrestrial forager, probing the ground for insects and other invertebrates, occasionally also feeding on seeds, small vertebrates and nectar. It is a largely crepuscular animal; it’s closest relatives are the nocturnal jeeper-creepers and the cathemeral anteater birds, from which it diverged around five million years ago, suggesting that the common ancestor between these taxa was already specialised to forage on lowlight conditions.

Titicula generally breed during monsoon months, which is where a dramatic shift from their usual lifestyle takes place. Males, which already have atypically serrated bills, develop longer keratinous “teeth” with distinctive inner grooves. During this period they produce a strange substance in their saliva, that often bubbles up, making them look rabid. These are adaptations to the bird’s atypical and terrifying breeding habits.

The first thing the male does after developing these features is search for a large mammal. Pretty much every lemurian mammal species that weights more than 50 kg is at risk, but the Titicula has a special prefference for elephants and large gondwanatheres. The male Titicula is rather picky about its target, usually preffering healthy males or lactating females. Once he finds a suitable target, the male flies up to it and bites, injecting the substance as rapidly as possible. Then he flies off, and waits. The saliva substance contains a strong neurotoxin that paralyses the victim for the span of an hour or more, inducing a state akin to sleep paralysis. The notoreceptors are left unaffected, and may actually become more sensitive.

Once the animal can’t fight back, the male begins his gruesome work, biting through the flesh with his serrated beak. Usually he takes advantage of already existing wounds, but he is perfectly capable of perforating thick hides on his own. Regardless, he will eat his way, creating a 30 cm deep tunnel, carefully angled as to not chance into vital organs or major blood vessels, yet lodged deep enough so that its impossible for the victim to crush him to death once he’s inside. As he eats, he licks the surrounding flesh, spreading his antiseptic substance to help the victim remain infection free and suffer less from bloodloss. At the end of the tunnel, he forms a cavity up to twice larger than himself.

Once this is done the male will emerge from the hole, remaining in the vicinity of the victim as the effects of the neurotoxin pass. As he follows about he emits infrasound calls barely perciptible to human ears, warding off rivals and attracting mates. Once a potential partner appears, the male will lead towards the victim. If the female aproves, they mate, and the male afterwards paralyses the victim, allowing her to enter and deposit one or two eggs. This may go on for a couple of days, where the male will copulate with about three or four females and gather up a small clutch, before he permanently enters the cavity. Sometimes a rival male may be drawn by the calls and kick him and his eggs out, leaving the exiled male to start again the next year.

If things go without interruptions, however, the male will stay inside the victim, incubating his eggs for about two months. Periodically he will leave to deposit his bodily waste outside of the whole, the entrance becoming postule-like and full of pus, and occasionally he will eat chunks of flesh from the victim. Most of the holes are strategically located in the vicinity of adipose tissues, the male favouring the victim’s fat over other tissues. In the first few weeks the male is rather cautious about feeding, avoiding harming the victim, but as the incubation period nears its end he will become less hesitant, often eating indiscriminately and beginning to expand the tunnel. A Babana specimen was discovered with a two meter long tunnel inside, the bird having eaten around in several loops.

After hatching the chicks will remain inside the host for a few days, the male kicking out the shells. Already born with flight feathers, they soon climb out of the tunnel, leaving the host to forage outside. The male follows after, leaving the victim at last, his keratinous “teeth” falling off. He will look after his young for another month or so, before they fly off to start their own lives. Sexual maturity is reached at around 5 years of age, and individuals may not breed up to a 2 year interval.

The Titicula’s terrifying and gruesome breeding habits is one of Lemuria’s most mysterious adaptations. Based on genetic data, the Titicula is a very recent species, probably having evolved in the Pliocene. The oldest unambiguous evidence is a possible early Pleistocene Cawlanga skeleton in northwestern Lemuria, possessing ribcage bite marks that fit the male Titicula’s tooth-like serrations. How this method of breeding came into being is unknown, something made even more jarring given how the Titicula doesn’t possess obvious marker habits like commensal parasite feeding, nor do its closest relatives. A hypothesis is that its ancestors might initially have laid eggs on corpses, switching to live animals to avoid predation from scavengers. However, this behaviour is not observed in its closest relatives, nor does it explain the acquisition of its venom.

Suffice to say, the bird’s violent activities do take a toll on the victim. Though the insides are rendered infection-free, the end postules may develop necrosis, younger animals may die of shock and adipose tissue deprivation, and the mental trauma is very severe, particularly in elephants. However, there is a surprising beneficial aspect to this lifecycle. Most of the victims have improved immunological systems, suffering from grave infections and parasites less frequently than non-targetted individuals, and it seems that the antiseptical substance may significantly decrease the risk of cancer. Animals that do survive the first infection are likely to live longer, healthier lives, and posterior Titicula attacks will generally be less fatal, as the birds preffer to use already opened wounds to creating new ones.

Because Titicula target human beings, it has been suggested to have been one of the reasons why early hominid populations were restricted to the wetter eastern peninsulas, their rainforest habitats less attractive to these parasite birds. To the various lemurian cultures, reverence and disgust mark human relationships with this bird. Archaeological evidence is rife with pathological telltales of Titicula infections, and some cultures even encourage them, believing that individuals strong enough to survive the process emerge stronger as a result. The spread of Sammangal farming allowed the spread of open environments in which these birds thrived, further expanding their range across Lemuria. Lemurian Buddhist texts refer to the Titicula as one of the five great diseases, seeing it as a great source of suffering. Yet, attempts to eradicate this bird, both under Indian and European colonial rule, have proven fruitless, as not only is it adaptable but various cultures continued to prommote its infections in medicine.

There are naturally various names for the Titicula across Lemuria’s languages. The name itself comes from a francophone version of Common Werer tik-tik-va, “flesh biter”, first reccorded by George Cuvier, and certainly popularised due to its similarities with “Dracula”. Other names include Soreopeia tavanga (“organ raker”), Wava icharaia (“who causes suffering”) and Lemurian Tamil ceypavala (“torturer”)

Truly one of Lemuria’s most intriguiging life forms, the Titicula is rightfully feared, but wonderfully demonstrates the extremes natural selection can provide.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Species: South American Canids (Speothos, Chrysocyon, Lycalopex, Cerdocyon, Atelocynus)

This series focuses on helping people choose interesting species for their fursona through informing them of the many, often overlooked, species out there! This post is about South American canids, including false foxes.

──── ◉ ────

Bush Dog (Speothos venaticus)

The bush dog has 3 subspecies:

South American Bush Dog (Speothos venaticus venaticus)

Panamian Bush Dog (Speothos venaticus panamensis)

Southern Bush Dog (Speothos venaticus wingei)

It is oddly hard to find pics of the different subspecies, sorry

Size: 20-30cm (8-12in) height (at shoulder), 57-75cm (22-30in) lenght, 12-15cm (5-6in) tail lenght, 5-8kg (11-18lbs) weight

Diet: carnivorous, preys on large rodents

Habitat: lowland forests, wet savannahs, open pastures

Range:

Status: near threatened

──── ◉ ────

Maned Wolf (Chrysocyon brachyurus)

Size: 90cm (35in) height (at shoulder), 100cm (39in) lenght, 45cm (18in) tail lenght, 23kg (51lbs) weight

Diet: omnivorous, preys on small/medium mammals, birds, fish; eats fruit, tubers, sugarcane, other plants

Habitat: savannahs

Range:

Status: near threatened

──── ◉ ────

Hoary Fox (Lycalopex vetulus)

Size: 58-72cm (23-28in) lenght, 25-36cm (9-14in) tail lenght, 3-4kg (6-8lbs) weight

Diet: omnivorous, preys on invertebrates, rodents, birds; eats fruit

Habitat: woodlands, bushlands, savannahs

Range:

Status: near threatened

──── ◉ ────

Sechuran Fox (Lycalopex sechurae)

Size: 50-78cm (20-31in) lenght, 27-34cm (11-13in) tail lenght, 2.6-4.2kg (5.7-9.3lbs) weight

Diet: omnivorous, varied. Preys on invertebrates, rodents; eats carrion, fruit, seed pods

Habitat: deserts, dry forests, beaches

Range:

Status: near threatened

──── ◉ ────

Darwin's Fox (Lycalopex fulvipes)

Size: 48-59cm (19-23in) lenght, 17-25cm (7-10in) tail lenght, 1.8-3.9kg (4-8.7lbs) weight

Diet: omnivorous, preys on invertebrates, small mammals, reptiles; eats fruit

Habitat: southern temperate rainforests

Range:

Status: endangered

──── ◉ ────

Pampas Fox (Lycalopex gymnocercus)

Size: 51-80cm (20-31in) lenght, 2.4-8kg (5.3-17.6lbs) weight

Diet: omnivorous, preys on birds, small mammals, invertebrates; eats carrion, fruit

Habitat: montane forests, dry scrublands, wetlands

Range:

Status: least concern

Please note! The pampas fox has 3 subspecies!

──── ◉ ────

South American Grey Fox (Lycalopex griseus)

Size: 65-110cm (26-43in) lenght including 20-43cm (8-17in) tail lenght, 2.5-5.4kg (5.5-12lbs) weight

Diet: omnivorous, preys on small mammals, birds, reptiles, invertebrates; eats carrion, fruit

Habitat: varied; scrublands, steppes, forests

Range:

Status: least concern

──── ◉ ────

Culpeo (Lycalopex culpaeus)

Size: 95-132cm (37-52in) lenght including 32-44cm (13-17in) tail lenght, 5-13.5kg (11-30lbs) weight

Diet: carnivorous, preys on lagomorphs, small mammals

Habitat: varied; temperate rainforests, forests, scrublands, deserts

Range:

Status: least concern

Please note! The culpeo has 5 subspecies!

──── ◉ ────

Crab-Eating Fox (Cerdocyon thous)

Size: 64cm (25in) lenght, 28cm (11in) tail lenght, 4.5-7.7kg (10-17lbs) weight

Diet: omnivorous, preys on crabs, small mammals, birds, crustaceans, invertebrates, reptiles; eats carrion, fruit

Habitat: savannahs, woodlands, subtropical forests, shrublands

Range:

Status: least concern

Please note! The crab-eating fox has 5 subspecies!

──── ◉ ────

Short-Eared Dog (Atelocynus microtis)

Size: 72-100cm (28-39in) lenght, 9-10kg (19-22lbs) weight

Diet: mostly carnivorous, preys on fish, invertebrates, small mammals, birds; eats fruit

Habitat: rainforests, lowland forests, swamp forests, cloud forests

Range:

Status: near threatened

Please note! The short-eared dog has 2 subspecies!

──── ◉ ────

#fursona resources#furry#fursona#species#canidae#canine#speothos#chrysocyon#lycalopex#cerdocyon#atelocynus#bush dog#maned wolf#fox#foxes#false foxes#hoary fox#sechuran fox#darwin's fox#pampas fox#south american grey fox#culpeo#crab-eating fox#short-eared dog

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Say Hi to the Spotted Hyena

The spotted hyena is also known, perhaps most famously, as the laughing hyena (Crocuta crocuta). This species once ranged throughout Eurasia, but following the end of the Ice Age was restricted to sub-Saharan Africa. Today they can be found in many types of dry, open habitat, including savannah, semi-desert, and mountain forests. At times, the spotted hyena may also enter urban areas in search of food.

Unlike other hyenas, Crocuta crotuta is a predator, not a scavenger. They most commonly prey on wildebeast, but they may also hunt zebra, gazelles, Cape buffalo, and warthog. In addition, desperate times may cause packs to hunt on more dangerous prey such as young hippopotamus, giraffe, and rhinoceros. Spotted hyenas have incredible endurance, reaching speeds of 60 km/hr (37 mph); a single chase can last over 24 km (14 miles). When live prey is scarce, the laughing hyena can also turn to carrion, as well as snakes and ostrich eggs. In turn, this species may be killed by lions, though this may be motivated more by competition than prey drive.

Spotted hyena females are typically larger than males, weighing 44.5–67.6 kg (98–149 lb) to the males' 40.5–69.2 kg (89.3–153 lb). The height range for both sexes lies between 70–91.5 cm (27.6–36.0 in). In addition, female laughing hyena are somewhat famous for their masculinated genetalia; the clitoris is enlarged, resembling a penis, and is accompanied by sacs filled with fibrous tissue that resemble a scrotum. As the name implies, the coat is light brown with darker spots over most of the body. Because the species has such a wide diet, it has was is considered to be the strongest in relation to size of any mammal. The bite force is stronger than that of a brown bear, and can exert a force of 4,500 newtons-- enough to crush bone.

The laughing hyena is a highly social animal, and individuals live in communities up to 80 strong; size largely depends on prey availability and whether or not the group migrates. A clan territory can be anywhere from 40 km (24 mi) to 1000 (621mi) squared. Females dominate the males, and a pack is usually led by a matriarch. Hierarchies are strictly enforced, and positions are primarily inherited through birth and transferred through death. In addition, one's rank is maintained and recognized through social alliances and their contributions to the clan rather than size or dominance displays. The entirety of the clan comes together most often when defending a territory, gathering at the communal den, or at a kill; however, these kills are more commonly produced from smaller offshoots of the clan.

Crocuta crotuta can breed year-round, though mating is at its peak during the wet season from April to June. Members of both sexes pair indiscriminately with multiple mates, both within their clan and without. To offer himself, the male performs a mating ritual in which he lowers himself to the ground before the female, and retreats if any aggression is shown. Once impregnated, the female carries for about 110 days before giving birth to two cubs-- three is fairly rare. Weaning takes another 14 to 18 months, during which time cubs learn to hunt and defend the clan, as well as establish their place in the social hierarchy. Sootted hyenas reach maturity at about 3 years old, and can live an average of 12 years in the wild, though individuals as old as 25 have been recorded.

Conservation status: The spotted hyena has been determined Least Concern by the IUCN. However, outside protected areas the population is declining due to deforestation and hunting as a nuisance species.

If you like what I do, consider leaving a tip or buying me a ko-fi!

Photos

Augusto Bila

Elise Pianegonda

Evie Davidian

Art Wolfe

#spotted hyena#Carnivora#Hyaenidae#hyenas#carnivores#mammals#savannahs#savannah mammals#grasslands#grassland mammals#scrubland#scrubland mammals#africa#sub saharan africa#animal facts#biology#zoology#requested

175 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sikkim is a verdant paradise for aficionados of feathered creatures

Nestled in the heart of the Himalayas, Sikkim is a verdant paradise for aficionados of feathered creatures. The state's varying and diverse terrain, which encompasses alpine forests and subtropical zones, is inhabited by a dazzling array of avian species. From the splendid Black Drongo to the unusual Golden Eagle, the avifauna in Sikkim is nothing short of awe-inspiring. Whether you are a fledgling enthusiast or a seasoned observer, these birds of Sikkim are certain to astonish you. Hence, it is time to spread your wings and tick off these 20 awe-inspiring birds of Sikkim with the name from your birding checklist.

First on the list is the Brown Fish Owl (Ketupa zeylonensis), a remarkable bird that dwells in Sikkim's forests and rocky river valleys. As the moniker suggests, this bird feeds primarily on fish; however, it also consumes other small mammals, birds, and insects. The Brown Fish Owl is a large bird with unique brown and white plumage, and it has bright yellow eyes that add to its appeal. This nocturnal bird is renowned for its deep, resonant hooting, which reverberates through the forest at night, enhancing the mystical vibe of Sikkim.

Next, there is the Black Drongo (Dicrurus macrocercus), a familiar bird found in Sikkim's open woodlands, scrublands, and gardens. This medium-sized bird has a lustrous black plumage that stands out against the greenery, and it has a distinctive forked tail. The Black Drongo is a nimble flyer and is recognized for its impressive aerial acrobatics, diving and swooping through the air to catch insects on the wing. The bird is also celebrated for its distinct call, which resembles a series of clicks and whistles. The Black Drongo is a captivating bird to observe, and its sleek appearance and intelligence make it a favorite among birders.

The Great Crested Grebe (Podiceps cristatus), a large aquatic bird found in Sikkim's freshwater lakes and marshes, is another breathtaking bird. This remarkable bird has unique black and white plumage, and it has a striking crest on its head that gives it its name. The Great Crested Grebe is well-known for its stunning courtship display, which entails swimming alongside each other and rising out of the water in perfect synchronization. This bird feeds primarily on fish and aquatic invertebrates and is an adept swimmer and diver. The Great Crested Grebe is a stunning and graceful bird, and it is always a pleasure to see it in its natural habitat.

Finally, there is the Kashmir Nuthatch (Sitta cashmirensis), a small bird found in Sikkim's oak and rhododendron forests. This bird has unique blue-grey plumage and a black stripe on its head. The Kashmir Nuthatch is celebrated for its acrobatic abilities, and it can be seen clinging to tree trunks and branches while hunting for insects and spiders. This bird has a distinctive call that sounds like a high-pitched whistle, and it is always a pleasure to hear it in the forest. The Kashmir Nuthatch is an endearing little bird, and it is always a delight to spot it while birdwatching.

Full Article: https://www.gangtokian.com/tick-off-these-20-stunning-birds-of-sikkim/

0 notes

Link

0 notes

Photo

How the Enchanting, Elusive Pink Fairy Armadillo Became One Scientist's Obsession

In the arid desert of Argentina’s Mendoza Province, Mariella Superina waits patiently for a fantastic creature to emerge from its lair beneath the sands. Her quarry, the pink fairy armadillo (Chlamyphorus truncatus), looks like it could have scurried straight out of the illuminated pages of a medieval bestiary. The animal's shell, paws, and tail are a vibrant bubblegum pink that contrasts with its silky, milk-white fur and black eyes. About the size of a hamster—a mere six inches from head to tail and weighing just a quarter of a pound—it's the smallest of all armadillo species. It’s found only in Argentina, in a broad swathe of sunbaked scrubland that stretches from the foothills of the Andes to the coastal province of Buenos Aires. And that is about all we know of these wondrous animals. “They are a total enigma… We don’t even know if they are common or rare,” says Superina. In fact, some people doubt whether they’re even real. “The first question that hits on Google is, ‘Do pink fairy armadillos exist?’” says evolutionary biologist Simon Watts, author of We Can’t All Be Pandas (Ugly Animal Preservation Society). “‘Pink fairy armadillo’ does frankly sound fictitious.” Watts, whose podcasts and tv shows champion the less charismatic members of the animal world, doesn’t count the pink fairy armadillo as one of his unsung uglies—between its cotton candy colors and curious name, he says, “people tend to be fascinated when they hear of them.” Instant fascination was certainly Superina’s reaction the first time she saw one of the tiny mammals. “I was speechless,” she says. “At that moment I knew I wanted to learn everything I could about it. It became an obsession.” Originally from Switzerland, Superina began studying armadillos in western Argentina 25 years ago. Today, she leads an international team that monitors global populations of anteaters, sloths, and armadillos but, thanks to her pink fairy armadillo obsession, she has also become the leading expert on the diminutive and enigmatic animal. She even hosted a live pink fairy armadillo—which turned out to be a real diva—in her living room in the name of science. Studying the animal in its natural habitat, however, has eluded her—and everyone else. For centuries the armadillo has evaded the most determined scientists; even Charles Darwin failed to collect a specimen during his visit to Argentina. The pink fairy remains as mysterious as its name suggests because of its subterranean lifestyle, the result of adaptation to a changing environment millions of years ago. That’s when global climate patterns shifted, transforming the Andean foothills from grasslands into semi-arid deserts. As its habitat became less hospitable, the pink fairy’s ancestor retreated from the surface, evolving into a burrowing, or fossorial, animal. “Burrowing habits tend to appear when habitats become open, going from tree cover to grasslands or deserts, or when they get really hot,” said the University of Oregon’s Samantha Hopkins, who studies small mammal evolution, in an email. Underground, in the absence of predators, most of the pink fairy’s shell softened, losing its defensive function. It serves instead as an air conditioning system: In hot weather, the armadillo flushes its shell with blood, radiating heat and cooling down its core body temperature. Using its brawny foreclaws, the armadillo burrows through the sandy soil hunting for worms and insects. As it digs, it uses its armored butt plate to compact the loose soil in its wake, shoring up tunnels to prevent collapses. The elusive armadillo does appear above ground, when excessive rainfall—unusual in this desert region—floods its burrows. But the sight of a pink fairy is so rare that, “Octogenarians who have lived all of their lives in these rural areas (may have) seen this animal only once or twice,” says Guillermo Ferraris, a provincial ranger who works primarily in wildfire management. “But they never forget it.” When the pink fairy armadillo does leave its subterranean sanctuary, it encounters a bewildering and perilous world. Towns and vineyards are gradually replacing what was once vast scrubland. Herds of feral goats overgraze vegetation and compact the soil under their hoofs, hindering the armadillo's ability to dig its burrows. Oil fields and asphalt roads busy with trucks and cars bisect the desert landscape, isolating armadillos from one another. Out of their element, pink fairy armadillos are highly vulnerable to speeding cars and predators, including dogs and cats. Sometimes, however, Superina gets a call: A live armadillo has turned up. She rushes to the scene to collect data vital to understanding the species. “It's always a magical experience to see a pink fairy armadillo in the flesh, up close, but I put my awe to one side because we have to work fast to avoid causing any unnecessary stress, so we can immediately release the animal,” she says. On one occasion several years ago, however, she did take one of the rescued animals home. The provincial department of natural resources had requested her help: The idea was that, by studying the basic needs of an animal under her care, Superina could improve the chances of successfully rehabilitating injured armadillos, so they could be released back into the wild. Despite being obsessed with the armadillo, it was not an easy sell for Superina. “At first, I refused because these animals are very sensitive and usually die within a few days,” she says. “But then I realized that, for their conservation, we need to understand if it's possible to keep them alive in captivity.” Even now, as she recalls the event, she stresses that it’s not only illegal but also unethical to keep the animals as pets. Undertaking her role as armadillo caregiver required a special permit—and some serious home renovation. Ferraris, Superina’s partner, built a huge, sand-filled terrarium for the armadillo in their living room, creating natural hiding places and setting up infrared cameras to record its behavior. “It was quite an experience,” says Superina, laughing. “Our lives revolved around this pink fairy armadillo. We couldn’t go anywhere because we had to be in the house every night to care for it, and study its behavior.” “The armadillo would scurry around making this eerie, high-pitched scream.” The unusual houseguest was rather demanding. Superina brought it a variety of insects and worms, but the pink fairy turned up its pale nose at everything offered. Undeterred, the scientist tried one idea after the next. Finally, 36 meticulously-prepared recipes later, the armadillo tucked into a meal that apparently satisfied its gourmet tastes: a premium brand of cat food mixed with finely mashed banana, and sprinkled liberally with insectivore pellets. The finicky fairy would leave its burrow to eat the food at exactly 9 p.m. each night. “If only the slightest thing was moved in the terrarium, the armadillo would start scurrying around making this eerie, high-pitched scream until everything was put back exactly in the same place,” says Superina. Her fussy subject, alas, lived only eight months, but the experiment provided valuable information about how to care for injured individuals during rehabilitation. Learning about the animal in the wild, however, remains difficult. The pink fairy is particularly problematic because standard field observation techniques are of limited use. Radio transmitters used for tracking mammals, for example, are usually attached by placing collars around the neck; the armadillo’s body shape makes this nearly impossible. So Superina decided to use special glue to fasten a tiny radio transmitter to the pink fairy armadillo’s armored rear. When a farmer found one of the animals out and about, “We went and attached a transmitter and released it back into the desert,” Superina says. “And off it went, looking like a little bumper car with the antennae trailing behind.” The next morning they found the tracks in the sand and began following the signal to look for the animal—only to discover that the transmitter had fallen off while it was digging itself back underground. She’s now exploring other options to track the armadillos, including one that relies on an animal that is usually more foe than friend to the pink fairy: the dog. Superina is working with an organization that has successfully trained scent detection dogs in Africa to track down another secretive, armored insectivore: the pangolin. Superina hopes that a dog could be trained to locate pink fairy armadillos so researchers can fit them with improved radio transmitters. For Superina, the search for the pink fairy has taken on an added sense of urgency. So little is known about the species that scientists can’t say whether it’s endangered—or how climate change is affecting it. “We just don't know how these animals are going to cope,” Superina says. For now, she waits, with a tiny transmitter at the ready, for the next appearance of her obsession. Tracking the animal underground will be a scientific milestone, but, perhaps more importantly, says Superina, it will be “a small step to better understanding this species, its needs, and what it needs from us for its conservation.”

https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/pink-fairy-armadillo

0 notes

Text

The Nile monitor (Varanus niloticus) is a large member of the monitor family Varanidae which is native throughout most of Sub-Saharan Africa, particularly along the Nile River and its tributaries in East Africa. They have also been introduced to Florida where they have become an invasive species. These lizards are remarkably efficient climbers and swimmer which adapt easily to a variety of habitats including forests, savannahs, scrublands, and wetlands only really avoiding true deserts. Nile monitors feed upon Eggs, Invertebrates, Fish, Amphibians, Carrion, Birds, Other Reptiles, and Small Mammals. These lizards are themselves preyed upon by eagles, leopards, hyenas, crocodiles, and pythons. Reaching some 4 to 8ft (120 to 244cms) in length and 13 to 45lbs (4.5 to 20kg) in weight, nile monitors rank amongst the largest lizards on earth. They have muscular bodies, strong legs, and powerful jaws. They sport striking skin patterns, with are a variable mix grey, black, browns, greens, and yellows on the back and head with barring on the tail and legs. While their throats and undersides are an ochre-yellow to a creamy-yellow. They are a promiscuous species which breeds from june through October. After mating the female excavates a hole in the ground or in an active termite nest and lays 20 to 60 eggs. After an up to 12 month incubation the eggs hatch. Under ideal conditions a nile monitor may live up to 20 years.

#pleistocene#pleistocene pride#pliestocene pride#pliestocene#cenozoic#reptile#nile#monitor#lizard#africa

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Unveiling the History of Akamas National Park

From its humble beginnings in 1962, the Akamas Peninsula has been transformed from an abandoned limestone quarry into a vast national park. In this blog post, we will uncover the history of Akamas National Park and reveal why this national park is so important to Cyprus.

The history of Akamas National Park.

Located between Peyia and Polis Chrysochous, Akamas National Park covers an area of 8.9 km2 (3.5 square miles). The history of Akamas National Park stretches back thousands of years.

The archaeological remains found in Akamas National Park indicate that people lived in the area from 7000 BC to 2000 BC. During the Bronze Age, Akamas were the most important settlement in western Cyprus.

During the Christian period, Akamas became known for its monasteries, which were built in the 12th century. A monastery dedicated to St. John the Evangelist was located here.

Two important pilgrimages occurred in the area during the 14th century. The pilgrimage of St. John the Evangelist and the Great Lent pilgrimage took place in the area.

Akamas National Park was designated as a National Park in 1983.

The natural beauty of Akamas National Park.

The area of Akamas National Park is rich with natural beauty. The landscape is mostly untouched by humans, leaving many plants and animals to flourish. The National Park is known for its wide variety of fauna, such as the Loggerhead sea turtle and the endangered Mediterranean Monk seal.

The National Park has a wide variety of flora and fauna that can be viewed by visitors. It is one of the few locations where you can watch wild goats and donkeys. The Monk seal population is thriving and can be seen swimming in the waters. There are hundreds of species of birds that reside in the park.

The National Park also is home to many of the endangered plant species. There are over 300 different species of wildflowers in the Akamas area. Many of the plants in the area are so unique that they are protected by the European Union.

The incredible biodiversity of Akamas National Park.

Akamas National Park is one of the most biodiverse national parks in Cyprus. It is home to a variety of plant and animal species that are not found anywhere else on the island.

The park is also a great place to see eagles, gazelles, ibexes, and a variety of other wildlife. It is also home to the Akamas Lion Sanctuary, which is the only place in Cyprus where lions are kept in captivity.

The park is an excellent place to explore if you are looking for a diverse and unique environment. It is also a great place to relax and get in some hiking or bird-watching. If you're looking for a UNESCO World Heritage Site that is well-preserved, Akamas National Park is a great option.

The incredible variety of wildlife in Akamas National Park.

This National Park is home to an incredible variety of wildlife. The rich geological history of Cyprus combined with the unspoiled wilderness of this National Park, has allowed this ecosystem to develop and flourish.

Akamas National Park is an ancient landscape. This park covers more than 125 square km, which is almost 50% of the total surface of Cyprus. This huge area offers multiple habitats and ecosystems, including forests, wetlands, scrubland, rocky shores, sea cliffs, and sandy beaches. These ecosystems are home to 300 species of plants, 250 native and non-native species of birds, 36 species of mammals, and 5 species of reptiles.

This ecosystem is rich, not only in terms of its biodiversity, but also in significance and history. Cyprus has a long history. The remains of early civilizations like Neolithic and Phoenician settlements, as well as the Roman and Byzantine cities, can be found on the coast of the island. The geography of the region, however, makes it perfect for keeping the history of these civilizations secret. The steep cliffs along the coast make it difficult for ships to approach the shore, protecting these ancient settlements and making them difficult to spot.

The incredible biodiversity of the plants in Akamas National Park.

Found in Paphos District, some 40 kilometres from Limassol, the Akamas National Park is surrounded by Chrysochous Bay, which serves as a natural shelter for marine mammals and birds.

The park contains a wide diversity of plant and bird species, and its natural beauty, which includes its wide variety of flora and fauna, has earned it the title of one of Greece's most valuable natural areas.

The flora of the Akamas National Park reaches all the Mediterranean climate zones, from subtropical to Mediterranean, and includes 250 plant species, 40 of which are endemic.

Among the park's most famous plants is the Mediterranean Cypress and the rich collection of orchids.

The fauna of the Akamas National Park includes 127 species of birds, 21 species of reptiles, 9 species of amphibians, 9 species of mammals and 4 species of fish. The endemic species include the Mediterranean Monk Seal, Eleonora's Falcon, the Lesser Kestrel and the Cyprus Wheatear.

1 note

·

View note