#sea spider

Text

You’ve heard of the itsy bitsy spider, now meet the giant sea spider. 🕷️

Like spiders on land, sea spiders—also known as pycnogonids—come in a range of sizes and appearances. They’re widespread and occur across a variety of ocean environments. The deep sea is home to the giant sea spider (Colossendeis sp.), which can grow larger than a dinner plate. This spindly spider lumbers along the seafloor on jointed, stilt-like legs.

Instead of spinning a delicate web of silk to trap prey, a giant sea spider uses an elongate, tube-like proboscis to slurp up its prey. While studying the unique communities that form around decomposing whale carcasses on the deep seafloor, MBARI researchers observed a giant sea spider crouched over and clinging to the fleshy tentacle of a pom-pom anemone (Liponema brevicorne). Upon closer inspection, the sea spider was actually sucking out the juices inside the tentacle. Another sea spider was even observed clipping a couple of tentacles and taking its dinner to go!

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Source:

“The adults' inability to regrow lost body parts is likely why the juveniles' regenerative skills have gone unnoticed until now, researchers noted in the paper.”

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

There's been a distinct lack of invertebrates on my Wet Beast Wednesday posts so let's fix that by adding sea spiders. These arthropods are notable for being probably the creepiest things i've features on this series. Like I'm not afraid of actual spiders at all, but these things give me the heebie-jeebies. And I'm exactly the kind of person who loves to spread the things that creep me out, so let's combine thalassophobia with arachnophobia for the worst of both worlds! The first thing to know about sea spiders is that the name is a lie. They aren't spiders but instead members of their own class: Pycnogonida, meaning that a more accurate name is to call them pycogonids. Another alternate clade name is Pantopoda, which means "all legs", a pretty accurate description. They are traditionally classified as chelicerates, putting them in the same subphylum of life as proper spiders. However, this may change as a few genetic studies (Regier, et al., 2010 and Sharma et al., 2014) instead place them as a sister group to all other extant arthropods. Sea spiders occupy every part of the ocean with around 1,300 documented species.

(Image: a collage of many sea spider species, courtesy of ye olde Wikipedia)

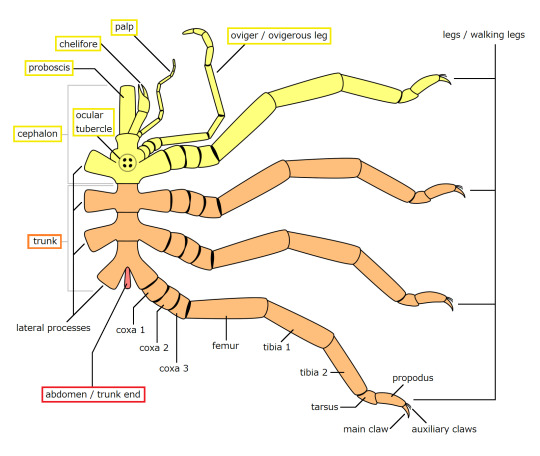

The first thing you'll likely notice about sea spiders is that their legs are much larger than their bodies. In fact, the body is so reduced that many of the internal organs have to extend into the legs because they otherwise wouldn't fit. Sea spiders have a wide range of sizes, with the smallest having a legspan of 1 millimeter and the largest having a legspan of 70 cm (2.3 ft). That is larger than my sister's dog. Most species are pretty small, with the very large specimens being the result of polar or deep-sea gigantism. Most species have 4 pairs of walking legs, but some have 5 or 6 instead. The body consists of 2 segments: a cephalothorax subdivided into a cephalon (head) and trunk, and a very tiny abdomen. The cephalon contains the first pair of legs as well as a smaller pair of legs called ovigers that are used to handle their eggs, for grooming, and courtship. Every sea spider has a proboscis on the cephalon that is their feeding appendage. Depending on species, they may also have a pair of palps and/or chelifores, smaller appendages used to manipulate food. Some species lack both the palp and chelifore and their proboscis is instead flexible and muscular. Many species have a structure on the cephalon called the ocular tubercle which contains the eyes, but some deep-sea species have lost their eyes entirely. The trunk contains the remaining legs. Finally, the abdomen is extremely reduced and almost completely vestigial.

(Image: a diagram of sea spider anatomy)

Sea spiders are carnivores, using their proboscises to pierce soft-bodied invertebrates such as cnidarians, sponges, and some worms. They have no respiratory organs. Instead, dissolved oxygen diffuses into the body through the legs. A small and long heart beats at 90 to 180 beats per minute, circulating hemolymph (bug blood) through the central body and giving them a high blood pressure. Oxygen in the legs is transported through repetitive motion called peristalsis in the parts of the digestive tract that extends into the legs. Sea spiders can move both by walking and swimming, which they achieve by beating their legs in a motion similar to opening and closing an umbrella.

(image: a sea spider riding a jellyfish)

Birds do it, bees do it, and weird underwater spider-beasts do it. With the exception of one known hermaphroditic species, all spiders are dioecious, which is a fancy way of saying they have distinct males and females. During mating, the male will climb on the female and they arrange themselves until their reproductive gonopores (which are eon the legs of course) line up. The female them releases her eggs, which the male fertilizes and catches with his ovigers. The male carries the eggs until the larvae are born, with the female providing no further care. Larvae are very simple, consisting of a head with the only appendages being the ovigers, palps, and chelicerae. The trunk, abdomen, and legs develop as the larva grows. Instead of growing the legs all at once, they will grow in during sequential molts. Some have suggested that the development of the larvae parallels the evolution of the ancestor of arthropods, starting out very simple and gradually evolving more complex structures. Scientists have observed 4 types of larvae: the typical protonymph, atypical protonymph, encysting, and attaching. Typical protonymph larvae are the most common and become free-swimming after hatching. Atypical protonymphs are similar, but will eventually find another animal to live on or in. Encysting larvae will find a polyp colony and burrow in. It then encases itself in a cyst and will not leave until developing into a juvenile. Attaching larvae remain attached to their father's oviger until developing into juveniles.

(Image: a male carrying his eggs)

(Image: a larva)

#wet beast wednesday#marine biology#biology#zoology#ecology#animals#invertebrate#arthropod#sea spider#animal facts

282 notes

·

View notes

Text

(submitted by @malwarewolf404)

(submission text: Can you diagnose him he has every disease)

Name: Skiktak Skittaroo

Skill: Crit Immune

Quote: "Woo yea babey I'm the king of the dance floor!!!"

#submission#bug diagnosis#sea spider#arachnid#spider#not really an arachnid or spider but tagging like that for phobia purposes#theyre chelicerates like arachnids but are their own thing

228 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sea spider (Nymphon sp.)

By: John A. L. Cooke

From: The Complete Encyclopedia of the Animal World

1980

#sea spider#arthropod#invertebrate#1980#1980s#John A. L. Cooke#The Complete Encyclopedia of the Animal World (1980)

295 notes

·

View notes

Note

AAAAAAAAAAAAAHHHHHHH

HIDE Me HES GONNA KILL ME I JUST ASKED A QUESTIONNNNN!

-hides behind her-

I JUST ASKED HIM WHY WE CANT CALL HIM MIKE AND I TEASED HIM AND NOW HE’s GOING TO KILL ME

What- WHO did you call Mike and WHY is he going to kill you for it?!

#across the spiderverse#into the spider verse#spider person#ask#miguel o'hara#sea spider#spideysona#ask blog

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Palaeoisopus, a devonian swimming pycnogonid/sea spider investigates a crinoid.

379 notes

·

View notes

Text

Polar gigantism and the oxygen–temperature hypothesis: a test of upper thermal limits to body size in Antarctic pycnogonids

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

Can't believe Armored Core 6's arachnophobia mode update

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Low-Poly Sea Spiders for our enjoyment!

Based loosely off the colossendeis proboscidae, with an alt color at a friend's suggestion~

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

Spider jumpscares, happy new year 🎉🎉🎉🎉

Wolf-spider belongs to @goat-bones (might be my favorite out of these tbh 😭😭)

Sea-Spider belongs to @sneakysnekbetch (water shading water shading water shading w)

Discospider belongs to @the-cat-and-the-birdie (she was a lot of fun to draw-)

#atsv#across the spiderverse#digital art#procreate#wolfspider#sea spider#disco spider#spidersona#others ocs#spider man oc#spiderverse oc#spiderman oc#gifts :3#yea#✮ Spider scribbles ✮

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Finally got to see new Spiderverse!

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Round 1 Match 8

Jerboa weirdness: "bro has stilts for legs. a dang bird-mouse. sneefing and snorfing"

Sea Spider weirdness: "At first glance they kinda look like spiders but their anatomy is so freakish and different it's just insane (some have even postulated they may not even be arthropods in the first place). Their intestine branches off and runs through each one of their legs. They're so thin they don't need a dedicated respiratory system and can breath through simple diffusion (through their legs, mostly. They're like 90% leg.). Some species are so small each of their muscles consists of one single cell while other species can have leg spans of about 50 cm."

71 notes

·

View notes

Note

quick say something funny

Sea spider

Order of marine arthropods

Sea spiders are marine arthropods of the order Pantopoda (lit. ‘all feet’), belonging to the class Pycnogonida, hence they are also called pycnogonids (/pɪkˈnɒɡənədz/; named after Pycnogonum, the type genus; with the suffix -id). They are cosmopolitan, found in oceans around the world. The over 1,300 known species have legs ranging from 1 mm (0.04 in) to over 70 cm (2.3 ft). Most are toward the smaller end of this range in relatively shallow depths; however, they can grow to be quite large in Antarctic and deep waters.

Although "sea spiders" are not true spiders, or even arachnids, their traditional classification as chelicerates places them closer to true spiders than to other well-known arthropod groups, such as insects or crustaceans. This is in dispute, however, as genetic evidence suggests they may be the sister group to all other living arthropods.

Description

Anatomy of a pycnogonid: a: head; b: thorax; c: abdomen 1: proboscis; 2: chelifores; 3: palps; 4: ovigers; 5: egg sacs; 6a–6d: four pairs of legs

Sea spiders have long legs in contrast to a small body size. The number of walking legs is usually eight (four pairs), but the family Pycnogonidae have species with five pairs, and the families Colossendeidae and Nymphonidae have species with both five and six pairs. Seven species distributed among four genera (Decolopoda, Pentacolossendeis, Pentapycnon, and Pentanymphon) have five pairs, and two species in two genera (Dodecolopoda and Sexanymphon) have six pairs. Pycnogonids do not require a traditional respiratory system. Instead, gasses are absorbed by the legs and transferred through the body by diffusion. A proboscis allows them to suck nutrients from soft-bodied invertebrates, and their digestive tract has diverticula extending into the legs.

A pycnogonid grazing on a hydroid

Certain pycnogonids are so small that each of their very tiny muscles consists of a single cell, surrounded by connective tissue. The anterior region (cephalon) consists of the proboscis, which has fairly limited dorsoventral and lateral movement, the ocular tubercle with eyes, and up to four pairs of appendages. The first of these are the chelifores, followed by the palps , the ovigers, which are used for cleaning themselves and caring for eggs and young as well as courtship, and the first pair of walking legs. Nymphonidae is the only family where both the chelifores and the palps are functional. In the others the chelifores or palps, or both, are reduced or absent. In some families, also the ovigers can be reduced or missing in females, but are always present in males. In those species that lack chelifores and palps, the proboscis is well developed and flexible, often equipped with numerous sensory bristles and strong rasping ridges around the mouth. The last segment includes the anus and tubercle, which projects dorsally.

In total, pycnogonids have four to six pairs of legs for walking. A cephalothorax and a much smaller unsegmented abdomen make up the extremely reduced body of the pycnogonid, which has up to two pairs of dorsally located simple eyes on its non-calcareous exoskeleton, though sometimes the eyes can be missing, especially among species living in the deep oceans. The abdomen does not have any appendages, and in most species it is reduced and almost vestigial. The organs of this chelicerate extend throughout many appendages because its body is too small to accommodate all of them alone.

The morphology of the sea spider creates an efficient surface area-to-volume ratio for respiration to occur through direct diffusion. Oxygen is absorbed by the legs and is transported via the hemolymph to the rest of the body. The most recent research seems to indicate that waste leaves the body through the digestive tract or is lost during a moult. The small, long, thin pycnogonid heart beats vigorously at 90 to 180 beats per minute, creating substantial blood pressure. The beating of the sea spider heart drives circulation in the trunk and in the part of the legs closest to the trunk, but is not important for the circulation in the rest of the legs. Hemolymph circulation in the legs is mostly driven by the peristaltic movement in the part of the gut that extends into every leg, a process called gut peristalsis. These creatures possess an open circulatory system as well as a nervous system consisting of a brain which is connected to two ventral nerve cords, which in turn connect to specific nerves.

Reproduction and development

All pycnogonid species have separate sexes, except for one species that is hermaphroditic. Females possess a pair of ovaries, while males possess a pair of testes located dorsally in relation to the digestive tract. Reproduction involves external fertilisation after "a brief courtship" [citation needed]. Only males care for laid eggs and young.

The larva has a blind gut and the body consists of a head and its three pairs of cephalic appendages only: the chelifores, palps and ovigers. The abdomen and the thorax with its thoracic appendages develop later. One theory is that this reflects how a common ancestor of all arthropods evolved; starting its life as a small animal with a pair of appendages used for feeding and two pairs used for locomotion, while new segments and segmental appendages were gradually added as it was growing.

At least four types of larvae have been described: the typical protonymphon larva, the encysted larva, the atypical protonymphon larva, and the attaching larva. The typical protonymphon larva is most common, is free living and gradually turns into an adult. The encysted larva is a parasite that hatches from the egg and finds a host in the shape of a polyp colony where it burrows into and turns into a cyst, and will not leave the host before it has turned into a young juvenile.

Little is known about the development of the atypical protonymphon larva. The adults are free living, while the larvae and the juveniles are living on or inside temporary hosts such as polychaetes and clams. When the attaching larva hatches it still looks like an embryo, and immediately attaches itself to the ovigerous legs of the father, where it will stay until it has turned into a small and young juvenile with two or three pairs of walking legs ready for a free-living existence.

Distribution and ecology

A pycnogonid in its natural habitat

These animals live in many different parts of the world, from Australia, New Zealand, and the Pacific coast of the United States, to the Mediterranean Sea and the Caribbean Sea, to the north and south poles. They are most common in shallow waters, but can be found as deep as 7,000 metres (23,000 ft), and live in both marine and estuarine habitats. Pycnogonids are well camouflaged beneath the rocks and among the algae that are found along shorelines.

Sea spiders either walk along the bottom with their stilt-like legs or swim just above it using an umbrella pulsing motion. Sea spiders are mostly carnivorous predators or scavengers that feed on cnidarians, sponges, polychaetes, and bryozoans. Although they can feed by inserting their proboscis into sea anemones, which are much larger, most sea anemones survive this ordeal, making the sea spider a parasite rather than a predator of anemones.

Classification

The class Pycnogonida comprises over 1,300 species, which are normally split into eighty-six genera. The correct taxonomy within the group is uncertain, and it appears that no agreed list of orders exists. All families are considered part of the single order Pantopoda.

Sea spiders have long been considered to belong to the Chelicerata, together with horseshoe crabs, and the Arachnida, which includes spiders, mites, ticks, scorpions, and harvestmen, among other, lesser-known orders.

A competing theory proposes that pycnogonida belong to their own lineage, distinct from chelicerates, crustaceans, myriapods, or insects. This theory contends that the sea spider's chelifores, which are unique among extant arthropods, are not in any way homologous to the chelicerae in real chelicerates, as was previously supposed. Instead of developing from the deutocerebrum, they can be traced to the protocerebrum, the anterior part of the arthropod brain and found in the first head segment that in all other arthropods give rise to the eyes only. This is not found anywhere else among arthropods, except in some fossil forms like Anomalocaris, indicating that the Pycnogonida may be a sister group to all other living arthropods, the latter having evolved from some ancestor that had lost the protocerebral appendages. If this is confirmed, it would mean the sea spiders are the last surviving (and highly modified) members of an ancient stem group of arthropods that lived in Cambrian oceans. However, a subsequent study using Hox gene expression patterns consistent with a developmental homology between chelicerates and chelifores, with chelifores innervated from a deuterocerebrum that has been rotated forwards; thus, the protocerebral Great Appendage clade does not include the Pycnogonida.[self-published source?]

Recent work places the Pycnogonida outside the Arachnomorpha as basal Euarthropoda, or inside Chelicerata (based on the chelifore-chelicera putative homology).

Group taxonomy

According to the World Register of Marine Species, the order Pantopoda is subdivided as follows:

suborder Eupantopodida

including the following superfamilies:

Ascorhynchoidea Pocock, 1904

Colossendeidoidea Hoek, 1881

Nymphonoidea Pocock, 1904

Phoxichilidoidea Sars, 1891

Pycnogonoidea Pocock, 1904

Rhynchothoracoidea Fry, 1978

suborder Stiripasterida Fry, 1978 including the following family:

Austrodecidae Stock, 1954

suborder incertae sedis, including the following extinct genera:

Flagellopantopus Poschmann & Dunlop, 2005 †

Palaeothea Bergstrom, Sturmer & Winter, 1980 †

family Pantopoda incertae sedis, including the following genera:

Alcynous Costa, 1861 (nomen dubium)

Foxichilus Costa, 1836 (nomen dubium)

Oiceobathys Hesse, 1867 (nomen dubium)

Oomerus Hesse, 1874 (nomen dubium)

Paritoca Philippi, 1842 (nomen dubium)

Pephredro Goodsir, 1842 (nomen dubium)

Phanodemus Costa, 1836 (nomen dubium)

Platychelus Costa, 1861 (nomen dubium)

This taxonomic classification replaces the older version in which Pantopoda is subdivided into families as follows:

Ammotheidae

Austrodecidae

Callipallenidae

Colossendeidae

Endeididae

Nymphonidae

Pallenopsidae

Phoxichilidiidae

Pycnogonidae

Rhynchothoracidae

Fossil record

Although the fossil record of pycnogonids is scant, it is clear that they once possessed a coelom, but it was later lost, and that the group is very old.[citation needed]

The earliest fossils are known from the Cambrian 'Orsten' of Sweden, the Silurian Coalbrookdale Formation of England and the Devonian Hunsrück Slate of Germany. Some of these specimens are significant in that they possess a longer 'trunk' behind the abdomen and in two fossils the body ends in a tail; something never seen in living sea spiders.

In 2013, the first fossil pycnogonid found within an Ordovician deposit was reported from William Lake in Manitoba.

In 2007, remarkably well preserved fossils were exposed in fossil beds at La Voulte-sur-Rhône, south of Lyon in south-eastern France. Researchers from the University of Lyon discovered about 70 fossils from three distinct species in the 160-million-year-old Jurassic La Voulte Lagerstätte. The find will help fill in an enormous gap in the history of these creatures.

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

Guys I need help to win an argument against Deadpool.

If you put frosting on a muffin, is it a cupcake?

Please we’ve been arguing about this for like 3+ hours…

#roleplay blog#spider person#across the spiderverse#into the spider verse#sea spider#spideysona#ask blog

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

100 Days of Sea Creatures Day 24 - Giant Sea Spider (Colossedeis colossea)

#artists on tumblr#artists on instagram#deep sea#deep sea creatures#sea spider#marine invertebrates#sea creature art#sea creatures#inverts#eerie art

7 notes

·

View notes