#shihameta

Text

I've already added this in a later update to my Sora meta, but I figured I should go into this in a little more detail. Between Adventure and 02, Sora switches her sport from soccer to tennis, and the reason that's actually given in explicit text is that it's part of her bonding with her mother (since her mother played back in the day and is now her personal coach). But there's actually another implied reason that's a bit lost in cultural translation, and in fact, from what I understand, most Japanese fans already assume that this was the case despite it never being stated in dialogue:

Sora probably didn't have a choice even if she wanted to, because Odaiba Middle School probably didn't have a girls' soccer club.

There are enough Japanese middle schools that don't have girls' soccer clubs that this is actually a fairly frequent story you hear among girls who played soccer in elementary school (and especially so in 2001, when Sora first entered middle school). In such a situation, if Sora wanted to continue soccer, she would have two choices:

Brute-force herself onto the boys' club: In fact, this is implied to be exactly what she did in elementary school after she self-exiled herself from the girls' club (based on her testimony from Adventure episode 26). But while elementary schools are fairly lenient about this, middle schools are not, and Sora would be up against school staff advising her against it as well as potential scorn from the team itself. Indeed, if you look at the results of a survey held by the Japan Football Association, 68% of girls who played soccer in elementary school were affiliated with the boys' team, but only 20% did so in middle school (and this is from 2009, a whole decade later, so the numbers were probably even lower in 2001!).

Find a neighborhood girls' soccer team: Even outside school clubs, there are still independent soccer teams, so it would theoretically be possible to continue with the sport as an extracurricular activity. But that would mean potentially making a long commute (depending on where the nearest team is) and dedicating extra time on top of required school club activities, something that a lot of girls in real life don't have the luxury of doing.

So while she could have gone for it if she really, really wanted to, at this point, she would have to be willing to push for it to "considering going for the Nadeshiko League" levels (and according to former Nadeshiko League player Yoshino Yuka, who had to commute an hour's distance by train to continue playing soccer in middle school, it's not something that's easy to pull off for a lot of girls and their families even if you do have that level of dedication). Of course, there's no doubt that this is an unfair, unfortunate situation no matter how you look at it, but it's one that Sora would have realistically been likely to face in 2001, and given that she was never particularly depicted as being attached to soccer beyond hobby level in the series, it's easy to imagine that she would have decided to take an alternative route in order to continue playing sports instead.

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

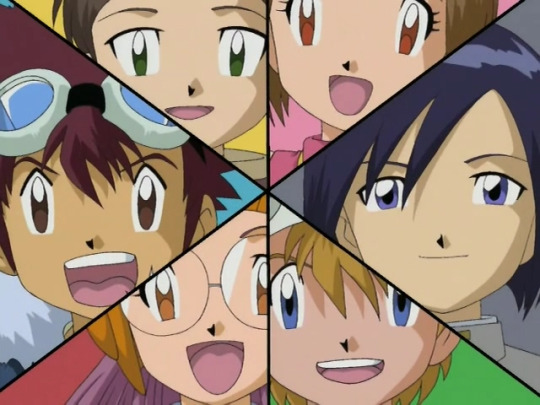

Digimon Survive’s character cast, their roles in the group, and Adventure parallels

This franchise loves to self-reference, so it’s very easy to say that a lot of things are based on Adventure, but in Survive’s case, it has been abundantly clear (to the point of having been officially stated in many interviews) the narrative and setup itself is meant to be a reimagining of Digimon Adventure, as in the 54-episode series that aired from March 1999-2000. As much as the franchise likes to use Adventure symbolism, or rough glosses of its isekai premise, you might be surprised at how few things actually have bothered to take a look at the entire series and structure to the little things, trying to figure out what made it tick, instead of just pulling its names and faces and terminology and calling it a day. Moreover, one of Survive’s core premises of “a Digimon partner is effectively a part of your own soul” is a premise that originates directly from Adventure; it’s just that this time, it’s much more explicit.

Adventure is famous for being a character narrative, to the point you can put a picture with nothing but the characters and people will consider it representative of the entire series. So if you want to go deeply into Adventure, you have to look at its characters, what their relationships were, and what roles they had. And Survive does, but with its own distinct cast of characters who are very similar in some ways...and very different in others.

As you might expect, this post spoils all four routes, so please be aware of this before reading further. (I also will be spoiling Adventure and 02, in case you haven’t seen those yet. Hey, you never know.)

Because I wasn’t able to go back through all four routes to take screenshots, the screenshots used in this post are from Anthony (Wrathful), Owl-Quest (Harmony), and BattleBunny (Moral and Truthful)’s playthroughs. Please go check them out if you want to see the game yourself!

Something very important before we begin

I think making comparisons and drawing parallels is very useful, but I have a personal policy that comparisons should only be drawn “as much as they are useful” and no more than that. There’s a difference between “thoughtfully inspecting comparisons and contrasts to analyze how things work” versus “forcing parallels so hard that you end up trying to smash a square peg into a round hole, completely losing sight of the reason you’re trying to make those comparisons in the first place”. I know it’s tempting to try and make as many parallels as you can, but there’s a point where trying to force it becomes actively detrimental to your analysis.

It is true that Survive was built from the ground up as a reimagining of Adventure of sorts, and even promoted and officially stated to be such. However, Adventure is Adventure, and Survive is Survive. Survive is a game meant to stand on its own even if you've never touched Digimon Adventure in your life; to act as if the narrative and characters are nothing more than variations on Adventure’s is, in my opinion, disrespecting Survive’s efforts to be its own story in the end. It is a game that pays tribute to and reimagines Adventure's concepts, so it can't (and shouldn’t) be disentangled completely from Adventure if you want to bring the most out of an analysis, but it’s also unfair to treat the game as if it’s just some kind of twisted, barely-modified parody of Adventure, because it’s not. It’s a game that draws heavily from its predecessors in bringing up concepts to think about while also firmly doing what it needs to do in order to be its own story.

Therefore, in making character comparisons and analyzing the characters in relevance to Adventure characters, my priority will be on making connections between “their roles and positions in the group” rather than trying to force comparisons for the sake of forcing them, or trying to claim that this character is just the Survive version of this Adventure character. In fact, in some cases, my goal is to convey that a Survive character may start off in the same rough position as their Adventure counterpart but go in a very different direction.

I also would like to reiterate that I very much disapprove of the idea of using Survive to be condescending about Adventure. Survive’s characters and plot do address territory that Adventure isn’t able to, but framing Survive with reductive things like “Adventure but darker/edgier” or “a deconstruction of Adventure” as if the game only exists to dunk on Adventure’s idealism or treat it like it’s implausible is incredibly disrespectful, not only to Adventure but also to Survive, which in fact very obviously holds its predecessor in high esteem. (I mean, it is very fun to refer to Survive as “Adventure except people die” as a joke, but the game really is more than just that.) I’m going to bring back this very well-worded tweet “a deconstruction is when I like something in a genre I disrespect”; I don’t have any patience for this kind of thing, so don’t bring it in here. I reiterate: the comparisons are going to be drawn for the sake of better analyzing what Survive is pulling from and referencing while also doing its own thing for its own story. No more, no less.

Takuma and Agumon

At this point it’s pretty much common knowledge that anyone with a name that starts with “ta-” and a pair of goggles is going to be taking Taichi’s role as protagonist, and Takuma having an Agumon only drives it in further, but if we’re actually going to talk about Taichi himself, things get a little more complicated because Taichi was actually quite unusual in many ways (I honestly would say that Taichi is a character a lot of people “know” but don’t tend to easily “understand”). But right off the bat, Takuma turns out to have a very different temperament from Taichi’s, being significantly more introspective and less impulsive. In fact, he holds the distinction of being a rare Digimon protagonist who uses the polite first-person pronoun boku (most Digimon protagonists use the more assertive ore), and for frame of reference, the other major players who do this are Takato (Tamers), Haru (Appmon), and Keisuke (Hacker’s Memory), all three of whom are associated with some kind of meta element questioning whether they should be in the protagonist position...

(Personally, between Takato, Haru, and Keisuke, I’d say Takuma is probably closest to Haru in that he’s polite but also very thoughtful and introspective. He does happen to have self-doubts much more quickly than Haru would most of the time, but he’s not prone to Keisuke’s self-esteem issues or Takato’s tendency to shrink easily.)

Some of the nuances of Takuma’s personality and how selfish or selfless he is depend on the player’s choices and what route things are in, but for the most part the general core is consistent across all four routes. Takuma doesn’t start off thinking of himself as the group’s leader, and this part is consistent with Taichi as well; Taichi didn’t have particular awareness of himself as the group’s leader until Jou confronted him with the prospect in Adventure episode 28. However, in contrast to Taichi immediately taking initiative and pulling everyone forward even if he didn’t consciously see himself as the leader, Takuma started off still having strong awareness of seniors like Aoi and Shuuji, and it only slowly becomes apparent that he’s taking charge as more and more characters start pointing it out, culminating in multiple characters pretty much unanimously considering Takuma the group’s leader even before he’s considered it; Part 9 on the Truthful route has Shuuji outright admit to Ryo that he’s using Takuma as his model for how a leader should actually be.

So how does Takuma end up becoming unanimously considered the leader in a similar way to Taichi despite having such a different temperament? The characters spell it out in clear words multiple times over the course of the game: he brings the group together by being their emotional center. That part about being their “emotional center” is important because Taichi wasn’t necessarily as good at that part (which incites a lot of conflict between him and the others during the last arc of Adventure), but the reason this is more important for Takuma is that the Survive group is significantly more prone to infighting than the Adventure group was most of the time. When the game’s producer Habu called it the “Lord of the Flies” counterpart to Adventure’s “Two Years’ Vacation”, Adventure’s director Kakudou revealed that Lord of the Flies was an inspiration for the part of the story corresponding to Pinocchimon and Yamato...which resulted in Taichi failing to keep the group together and everyone falling apart. So in other words, Takuma is pulling off the achievement of keeping the group glued together when the equivalent of the Pinocchimon arc is happening all the time. There are no Crests in this narrative, meaning the automatic filtering for “naturally good kids” was absent and the kids were dragged into the Digimon world by sheer virtue of being in the wrong place at the wrong time, leading to a lot more negativity on all fronts and composures lost much more easily -- and thus, Takuma’s ability to keep a cool head and get everyone to calm down becomes his most important asset.

Also of note is Takuma’s own relationship with Agumon. While Agumon in this game is obviously based off Taichi’s Agumon in Adventure, Takuma and Agumon end up having quite a lot of conversations together where Takuma consults with him on how to sort out his emotions and what to do next, far more so than would happen in the original Adventure. Part of this is simply because of the medium shift (being a video game, Survive is able to have much longer conversations that aren’t restricted by timeslot airtime), and it’s also not like Agumon in Adventure wasn’t also emotionally insightful when Taichi needed advice, but Takuma and his Agumon partner end up having several conversations on the vein of Adventure!Agumon’s discussions with BlackWarGreymon in 02 episodes 32 and 46. In the end, the main reason is probably just that Takuma is just that kind of introspective person who actively seeks out Agumon and talks to him honestly, allowing them to get borderline philosophical without any strings attached.

Minoru and Falcomon

The mere suggestion that Minoru is supposed to be Koushirou’s counterpart would probably make someone roll their eyes and go “oh, come on, now you’re really forcing it,” and I wouldn’t blame anyone for thinking so. Temperament-wise, Minoru couldn’t be any more different from Koushirou. Rather than anyone in the Adventure group, he comes off as a kind of mix of Daisuke (in terms of being rough but friendly and having a forward-thinking attitude) and Miyako (in terms of being a “mood maker” who tries to keep everyone’s spirits up but needs to be reined in by a more stoic partner). But trust me, hear me out, I know this sounds weird, but I’ve got more reason for this stance than you might think!

Actually, Koushirou had a pretty complex role in Adventure, to the point he seems to have two counterparts in Survive. The more well-publicized parts of Koushirou’s profile involve his intellectual curiosity (bringing him closest to the secrets behind the Digital World) and his sense of deference and politeness, and those traits correspond more to the Professor (more on that when we get to his section). However, the less well-publicized but no less important part is that Koushirou was, for all intents and purposes, Taichi’s right-hand man, and thus one of the most important figures in helping Taichi pull off what he needed to as leader.

Koushirou was one of the few kids who knew Taichi prior to the events of the series and had already established a certain sense of respect for him (he only went to camp at all because of Taichi). As a result, while Koushirou tended to avoid confrontation with the others in the group, he was open to Taichi in a way he often wasn’t with others, and Taichi likewise was comfortable asking him for assistance (culminating in the famous moment in Adventure episode 28 when Taichi uses his authority as leader to appoint Koushirou as the best person to solve the card puzzle). Later, it’s Koushirou who sticks by Taichi when the group splits up during the Dark Masters arc, Koushirou who witnesses and hears out Taichi during one of his biggest emotional breakdowns in Adventure episode 48, and Koushirou who works directly alongside Taichi in Our War Game! Taichi’s relationships with Yamato or Sora tend to be more well-publicized, so casual fans of Adventure or mainstream media reports tend to completely gloss over this, but it’s conspicuous to anyone who knows Adventure on a particularly deep level. (While this analysis sticks purely to the original Adventure and 02 for the sake of consistent scope, it says something that even stage play writer Tani Kenichi clearly also caught onto this and had the lines "I've watched you at your side all these years! Isn't that right?!" and "But I thought you could at least speak honestly with me!" come out of Koushirou’s mouth.)

So as much as Minoru isn’t really much of a counterpart to Koushirou in terms of personality, he is in terms of Koushirou’s “position in the group”: the leader’s right-hand man who avoids inciting confrontation but is vital in helping keep them together. (In fact, the part about avoiding confrontation is pointed out quite directly in his official profile.) Considering how Takuma pulling off the feat of keeping everyone together required him to have a very different temperament from Taichi, it thus follows that Minoru’s temperament needs to be different from Koushirou’s in order to achieve the same effect with the Survive group. Koushirou’s more polite and level-headed demeanor was important to keeping the rather impulsive Taichi in check, but in this case, Takuma is already plenty level-headed by himself, and Minoru being more actively sociable and trying to keep everyone’s spirits up is a more effective complement. This is helped by the fact that, in the same way Koushirou knew Taichi from the soccer club even prior to Adventure, Minoru happens to have already been Takuma’s friend from school prior to Survive, and thus by the time we get to the final chapters of the game (especially in the Truthful route), it’s made quite clear that Minoru really is Takuma’s right-hand man whom he can rely on for many things. On top of that, Minoru being so agreeable makes him the only character of the group besides Takuma to survive all four routes -- he sticks by Takuma no matter what.

Background-wise, Minoru’s is quite different from Koushirou’s in that he’s mostly used to being rather lonely at home due to a divorced father and a workaholic mother, and he also happens to be a fan of hero manga and tokusatsu to the point a lot of his personal ideal throughout the game is to become a “hero”. (Perhaps fittingly, his temperament is probably the closest to the shounen protagonist archetype among this group.) This puts him in an interesting position in that he’s the most aware of what kind of heroic character would be from a series like Digimon Adventure and personally strives to be one, even though it takes him a while to gather up the courage for it. When you have affinity-affecting choices with him, he tends to prefer the “forward-thinking” kinds of responses that would make Daisuke proud, so he clearly took the kids’ media lessons to heart. In line with that, Minoru is the only character besides Takuma to survive all four routes; while his biggest emotional turmoil happens in all four routes (it takes up the majority of Part 6), he and Falcomon weather through it quite well. But when you think about it, back in the Adventure universe, the kids who admired the Adventure kids most were...well, the 02 kids, so perhaps it’s not actually that surprising Minoru’s temperament is closer to them.

Also, here’s another fun thing to consider: Minoru’s dynamic with Falcomon takes several pages from Miyako and Hawkmon’s book...so, remember who also happened to be Koushirou’s junior who admired him the most?

Aoi and Labramon

If you wrote a rough base outline of Sora and Aoi’s characters, they’d probably be pretty similar or even identical. You’d basically get something like “the Mom Friend who tries to take care of everyone and overwhelms herself in the process, crumbling under the pressure”. But there is one key distinction that makes all the difference: Sora’s desire to help others was something that came naturally to her despite her own lack of self-awareness, whereas Aoi’s woes come from the fact she’s all too aware of the fact everyone is relying on her and bears resentment about it.

One recurring thing with Sora was that her own self-evaluation was often much harsher than she actually deserved. Initially scoffing at the idea of being responsible for someone else (Adventure episode 4), despite being unable to abandon everyone and constantly going out of her way to help everyone behind the scenes (Adventure episodes 22-25), her own self-evaluation was still that she was apparently devoid of love and didn’t care about the others at all (Adventure episode 26). Her constant desire to help everyone was effectively compulsive, and she had poor awareness of whether she was getting in over her head, with others needing to remind her that she shouldn’t see things as an obligation (Adventure episode 51). Sora was barely even aware of how much she was putting out for others because she saw it as an impulsive obligation, and the others were the ones concerned about whether she was taking enough care of herself. Moreover, although Sora bottled up quite a bit of self-imposed pressure, she wasn’t exactly shy about expressing her feelings; it’s just that they often happened to be messy, and she wasn’t sure what to make of them.

(By the way, this is also why I really don’t like the idea that Adventure is somehow more “unrealistic” or even “idealized” than Survive’s just because they’re ostensibly more put-together and selfless people, because Adventure’s characters often toed on the other extreme of being selfless to self-destructive levels; the kids would be prone to severe self-confidence issues or even self-hatred, especially going into 02. While the Survive kids may seem overall self-centered at first and thus be more prone to infighting, any self-worth issues they have or attempts at reckless self-sacrifice don’t tend to be as frequent or extreme as they were with the Adventure and 02 kids.)

In contrast, Aoi is consciously aware of what’s on her plate, what she’s dealing with, and why she’s doing what she does. Sora was the same age as Taichi and Yamato, so she was able to be comfortable in a position as their peer, but Aoi is one year older than Takuma and therefore considered one of the seniors of the group, a fact that’s alluded to multiple times over the course of the game. This means the group ends up treating her with the expectation that she has responsibility for them (especially after Ryo and Shuuji die in the main routes, thus genuinely leaving her as the oldest one there), and on top of her class president duties, she’s surrounded by expectations and responsibilities that are actually imposed on her. On top of that, people actually take advantage of her kindness and exploit her, and she knows this fact very well and hates it. (While it’s possible this might have happened with Sora, it’s unlikely she would have even realized she was being taken advantage of, much less come to resent anyone who did, because the issue was more about her own difficulty with setting boundaries and doing something for herself.)

Aoi does what she does because “she wants to be helpful”, so she suppresses all of her angry feelings and resentment to not burden anyone; for the early parts of the game, Labramon openly voices all of the snark and harsh burns that Aoi clearly wants to say but won’t. This means that meeting Saki inspires a mix of admiration and envy for the fact Saki is able to express her feelings so openly. But in the Wrathful route, when everything goes to hell and Saki (somewhat) sacrifices herself for Aoi, Aoi implodes from the resentment of everyone burdening her with responsibilities, seeing their attempts to give her space as not caring enough about her, and upset that after all of her desire to be “helpful”, everything actually just got worse. The last straw is when Piemon exploits her kindness to attempt to murder her, and the end result is Aoi completely flipping into “the ultimate selfishness” (absorbing Labramon, as in her own ego) to decide that the best solution would be to impose her way -- the way she’d never been getting all of this time -- on others and force them to agree with her.

Thankfully, Aoi fares better in the other routes where she manages to trust and rely on others a little more, and her friends do much more to make sure she knows her efforts are appreciated. Notably, during her affinity choices, Aoi reacts very well to choices that validate her right to have “shallow” interests like cute things (instead of it being considered undignified and immature of her) and choices that have other characters outright call her a Mom Friend. I’m pointing this out because for all Sora is well-known among fans for being a Mom Friend, this wasn’t actually pointed out with this kind of wording in Adventure mainly because Sora wasn’t really seeing herself as one, but here Aoi does prefer to be seen this way, presumably because it affirms the fact her friends appreciate her as a person rather than someone to dump responsibilities on.

As an aside, the Wrathful route involves a subplot about Kaito being one of the first to catch onto what’s going on with Aoi and make the most prominent attempt at reaching out to her, and while I don’t know if this was intentionally meant as a parallel, it does call back to the scene in Adventure episode 26 when Taichi and Yamato are at a loss as to how to help Sora during her emotional meltdown, and Yamato’s response (to let her cry if she needs to) is indicated as the better option until Takeru finally manages to step in with the best response. In Aoi’s case, given that she ends up resenting everyone giving her space (interpreting it as “leaving her alone”), Kaito’s attempt to get through to her by confronting her directly about her feelings was probably the closest to a step in the right direction -- it’s just that unfortunately Kaito doesn’t exactly handle it delicately enough to prevent Aoi from having a complete breakdown.

Fortunately, as if responding directly to this predicament, the Moral route contains a scene of them getting along perfectly well when going out to get food together. This is significant if you played Wrathful and Harmony before then, because both routes had one or the other fall off the deep end; Moral has Shuuji and Ryo’s deaths force them to step up to the plate, but without the exacerbating factors that drove both to to the brink in Wrathful and Harmony, it turns out they’re more than capable of stepping up to the task.

Ryo and Kunemon

While it’s generally easy to figure out at least some obvious parallels for each character in this cast, sometimes even multiple, Ryo is the one character I’ve never seen anyone really be able to get a read on regarding this question. I’ve seen suggestions that it might be Akiyama Ryou (based on the name) or even Ken (based on having a bug-type partner that he initially had a bad relationship with). Personally, my stance is “nobody, and that’s the point” -- because you’ll notice that the one thing all of these theories have in common is that none of them correspond to anyone in the original group from Digimon Adventure.

I’m not sure if this really comes across as well to anyone who hasn’t actually played the game hands-on, but one very striking thing about Ryo over the course of the beginning of Survive is that the game oftentimes feels like it’s tempting you to give up on him. The characters label him as unlikely to be cooperative right off the bat, and while they extend the minimum amount of courtesy to him, it’s also tinted with a sentiment that nobody really expects him to come along because he’s so pessimistic he’ll never cooperate. Getting his affinity level up to a significant amount in the early game actually requires you to go out of your way to seek him out and talk to him at least once (during a period the game interface doesn’t inform you that he’s available to talk like it does the other characters). And Ryo really is an uncooperative stick in the mud who doesn't look like he has any interest in helping himself anyway. They spoiled the fact he was going to be the first death before the game even released!

In other words, Ryo has no clear Adventure counterpart because “he has no place here”. He’s not a character who fits in the framework of Adventure-defined archetypes. He wasn’t made to be on a heroic adventure to begin with, and so he’s the first to be removed from it. And yet, the difference his presence or absence makes results in him being arguably one of the most important characters in this game.

In fact, even in the very, very early stages on the game, there were hints that Ryo’s behavior of being completely uncooperative and pessimistic were largely exacerbated by the stress of being brought to another world with monsters; if you closely watch him at the beginning of the game, he’s the one who enables Miu into taking them to the shrine (which he reminds us about near the end of the Truthful route). His website short story reveals that he’d actively decided to go to the extracurricular camp despite his initial misgivings because he really did want at least a little hope of making friends. But being jaded from isolation does a number on your abrasiveness level (the Frontier kids can testify to that one), and then everything went to hell when all of his stress factors and feelings of isolation were aggravated to their worst.

Depression isn’t an elegant thing, unfortunately, and Ryo’s inner desire to do better being blocked off by his initial difficulty to connect with others is perfectly exemplified by Kunemon trying really hard to take care of Ryo and communicate with others but being held back by his inability to use human language or do much with his limited physique. Note that Ryo’s initial hostile behavior towards Kunemon isn’t necessarily condescension or anything near the level of Shuuji’s initial bad relationship with Lopmon; it’s just that Ryo is afraid of Kunemon and not sure what to make of him, in the same way he’s clearly not sure what to make of himself. (Naturally, the first thing Ryo does when he comes back from the brink is start forming a proper relationship wtih Kunemon, and Ryo himself opening up more in the Truthful route correlates with Kunemon’s higher forms becoming able to speak.)

Ryo’s death in the three main routes is from a mixture of factors that even the cast in-universe isn’t sure what to make of; he doesn’t actively commit suicide per se, but his death wouldn’t have happened if not for his extreme suicidal ideation, and while Takuma regrets not having reached out to him earlier, it’s also not like he can be blamed for not doing enough when it wasn’t for lack of trying (from Takuma’s perspective, it’s not like he had any way of knowing that Ryo would die if he didn’t bond with him intimately in 3 chapters, and Ryo himself wasn’t exactly giving much of an indication that such a feat would actually be possible). Looking at the difference between the routes where he dies and the route where he doesn’t, the difference is that when Ryo dies, his pessimism about anything working out for him and him having a “place” anywhere convinces him he really doesn’t have anything to live for anymore, whereas the route where he lives has Takuma and the others so obviously risking life and limb to drag him back that he’s actually able to see, very clearly, that he did have a “place” and the ability to make friends after all.

(By the way, I should point out that one thing Survive is very good at is that a lot of the “correct” affinity choices are ones where you don’t pry too deeply into their problems and instead respect the other person’s space. In Ryo’s case, getting his affinity up quickly enough to save him requires going out of your way to check on him often, but the actual choices that raise affinity mostly involve validating his feelings and not prodding things too much, basically showing that you care but also respecting that he’ll open up when he’s ready.)

Having realized this, Ryo opens up immediately; again, he was interested in proactively making friends from the get-go, so it’s only natural that as soon as he confirmed that was a possibility for him and his initial shell was broken through, he didn’t hesitate to brighten up and actively engage with the others. Turns out, he's actually one of the most emotionally insighful people in the cast (in no part because, as someone who's seen the bottom, he's well aware of its horrors), but he also has a certain sense of grounded, to-the-point pragmatism while also not being as extremely emotionally charged as Kaito. Completely contrary to the bad first impression he gave everyone (except Saki), it turns out he’s actually a pretty great friend to have. And once Ryo is saved, the route automatically locks onto Truthful, because it creates a chain reaction where he ends up being the best person to save Shuuji, who then paves the way for the truth to be reached and the best possible ending achieved.

Remember how I said that Ryo was the character who had no place in the Adventure framework? If Ryo dies in Part 3, the “best” possible ending you can theoretically get (Moral) is the one that correlates most closely to Digimon Adventure, with the kids being booted out of the Digimon world for the time being and an uncertain future of whether the worlds can truly come together. Reaching an even better one that more closely represents what came after Adventure and allows the story to be passed onto future generations (very unsubtly represented by the Chibimon meeting new kids at the end -- note the significance because none of the 02 quartet’s Digimon are recruitable in the game) requires Ryo, the added factor who helps the story proceed.

But really, the ultimate take-home the game is making here is that you shouldn’t give up on people that easily, because they just might surprise you.

Saki and Floramon

Saki’s creed being to “go with her feelings” makes it immediately obvious off the bat that she’s the Survive counterpart for Mimi, but interestingly, Saki is simultaneously more rude and more kind than Mimi was in Adventure. Mimi had a “princess-like” demeanor based on her somewhat spoiled upbringing, meaning that on one hand she would be quick to complain and gripe about anything that even moderately annoyed her, but she also was constantly deferential and respectful to her elders, had consistent use of honorifics, and was always polite and careful not to step on anyone’s toes as long as she wasn’t emotionally overwhelmed.

On the flip side, Saki handles everyone somewhat bluntly (not even using upward-facing honorifics for most characters despite being one of the youngest in the group) and has less regard for what other people think when she says what she feels -- but she’s quite the opposite of spoiled. In fact, Takuma realizes after a fashion that she comes off as someone who’s been through hardship in the past, and she’s actually one of the most resilient in the cast; eventually, we find out that any “sheltering” she’s been through comes from the fact she wasn’t allowed to do much in light of her illness, and her emphasis on feelings and living to the fullest comes from the fact she’s not sure whether she might die soon. Moreover, the illusory versions of Saki encountered over the course of the game reveal that she’s actually afraid of being hated by others, so there is a certain aspect of her that’s self-conscious about whether she’s going too far.

In the end, Saki respects others’ feelings, but also expects to have her own feelings respected in turn. Throughout her affinity events, Takuma learns that although she initially seems flighty and difficult to predict in terms of how she wants to be treated, she’s a lot more considerate than she seems at first, and at no point does she deny anyone else’s right to feel the way they do as long as they respect her own. In addition, while she doesn’t believe in hiding how she feels, she also does take measures to try not to step on others’ toes (that is to say, she understands that she can’t just selfishly do whatever she wants without regard for others). Out of all of the deaths presented in the three main routes, Saki’s is perhaps the most purely selfless one as she knowingly accepts death in the face of her fear of it, as long as it saves others -- especially since the weight of “failing” her friends hangs so over her head that she loses all sense of self-worth.

The beginning of Part 5 of the Wrathful route reveals that Saki had been delaying a surgery out of fear of its outcome, despite the fact that it would greatly increase her chance of living longer if she takes it. It’s left ambiguous whether she does actually decide to commit to it after the events of the game, but the three endings where she survives (Harmony, Moral, and Truthful) confirm she at least lives for a year after the game’s events. One can only hope that the events of the game and her friends convinced her to have the courage to take it!

Incidentally, Adventure and 02 generally had a pattern that the characters with Digimon partners that were closest to their own personalities were the ones that usually were more straightforward -- so naturally, Saki and Floramon have the closest to identical temperaments from the very beginning.

Shuuji and Lopmon

Considering that Jou tends to be one of the most well-liked Adventure characters by adult fans, depending on how you look at it, it’s either deeply ironic or incredibly fitting (or both) that his Survive counterpart is turning out to probably be the most controversial character in the cast.

In fact, on the surface level, Shuuji’s profile is almost identical to Jou’s from temperament to backstory. He’s the oldest of the group (in this case, the only one in high school) and is therefore considered the “leader” with responsibility for everyone by default, but doesn’t really have the mettle to keep himself together for it at first. His sense of duty has roots in his family life, including a father who has high expectations of him and a shadow of an older brother looming over him. However, one factor makes all the difference here: Shuuji’s doing all of this specifically because he wants to please others and get their approval.

Jou wasn’t really all that worried about what others thought of him (other than the minimum amount of respect necessary to have faith in his ability to keep them together). The concept of “status” didn’t really play any sort of factor, and in fact, he was portrayed as even somewhat dragging his feet when it came to studies or social status. On top of that, poking into a 02 drama CD reveals that Jou’s dad wasn’t actually that controlling, and was perfectly willing to give his blessing to Jou about not becoming a doctor; it’s just that Jou knew that, emotionally speaking, he wouldn’t be very happy about it, so Jou was doing this because he just really cared about his dad’s feelings. Jou only didn't want to "disappoint" others because he happened to have a Good Samaritan nature of wanting to help others, and in fact it almost seemed he thought of himself too little to the point of having a rather recklessly self-sacrificial streak (Adventure episodes 7, 23, 36). When Jou said “because I’m the oldest”, what it meant was “because as the oldest, I take my responsibility to take care of everyone very seriously”.

In contrast, Shuuji’s fixation with being respected as the “leader” is decidedly less altruistic than Jou’s, and in contrast to Jou not really worrying that much about what others think of him, Shuuji believes he’s entitled to everyone’s respect and acts out of fear of abandonment. Of course, the beginning of Part 5 makes it clear why there’s such a huge difference here: instead of a father who was still ultimately supportive despite everything and two older brothers who looked out for him, Shuujii’s father is emotionally abusive, and while his brother doesn’t seem actively condescending per se, he seems to have a sense of resigned apathy and is only driving Shuuji’s inferiority complex in further. (While it wasn’t said in Adventure or 02 that Jou was necessarily concerned about being compared to his older brothers, there was a nuance Jou had a very intimidating “example” set by his university-aged brothers -- but that's also exactly why Shin pulled Jou aside to give him advice in Adventure episode 38.) With the fear of being "abandoned" instilled in him, Shuuji desperately tries to prove to everyone around him that he's capable of being a "leader", but his obsession with trying to force everyone's respect rather than doing anything actually worthy of it only earns him less respect, which he knows...leading to a very bad loop.

Shuuji's behavior of being a well-meaning abuse victim who ends up exhibiting abusive behavior as a maladaptive response to his trauma is unfortunately a very well-known cycle, especially in the way it manifests via his behavior towards Lopmon. In a moment of clarity at the beginning of Part 5, Shuuji does notice that Lopmon's behavior towards him mirrors his own behavior towards his father, but this only results in a slight improvement in their relationship (from “treating him like a disgusting monster” to “overworking him to uncomfortable extents”), with Shuuji treating Lopmon in the exact same way his own father treated him. If you know anything about typical maladaptive trauma behavior, it comes out most prominently when the person in question feels the safest -- when they feel threatened, they shrink under the trauma, and when they feel safe, they try to make use of the control of the situation they’d so desperately been lacking, resulting in them resorting to the only thing they know how to do. So ironically, Shuuji began behaving this way because he actually felt emotionally safer with the kids and with Lopmon than he did at home; in front of his family, he shrank and groveled at his father’s feet, but once he was in a situation he did have an opportunity for respect, he became overly controlling.

In three of the four routes, Shuuji dies a vicious and unfortunate death when his own negativity dark evolves (for lack of a better way to put it) Lopmon and symbolically results in him being destroyed by his own malice, but in the Truthful route, Ryo gives him a good smack in the face to bring him back to his senses. While it's implied that Ryo was in the best position to understand how necessary that was due to having personally experienced trauma himself, at the same time, it's also remarkable just how quickly Shuuji bounces back and completely changes his tune thereafter. In fact, it’s quite unlikely Shuuji himself wanted to be this kind of person, it’s just that this kind of behavior was the only way he knew how to respond. (Note the symbolism of Wendimon himself clearly being in anguish and effectively crying for help even after devouring Shuuji -- he was afraid of his own destructive qualities.) Even if Shuuji wasn’t necessarily dealing with a supernaturally implanted ball of darkness in the back of his neck, it is not entirely off to be making a comparison with Ichijouji Ken.

Shuuji’s role in helping achieve the Truthful outcome happens because he decides to become the Professor’s assistant, meaning that Shuuji is actually incredibly capable and intelligent to the point where his observations help the Professor reach a level of understanding he wouldn’t have been able to otherwise. Shuuji himself says that he decided to start working under the Professor because he wanted an adult’s example to follow, which is important because this is basically Shuuji realizing that the other adults in his life had failed him. For all his father gave him grief for being a bad leader, he wasn’t exactly setting a fantastic example himself about what a good leader should be, and Takuma notes that Shuuji is starting to take on some actual leadership qualities just by being more confident and being more assured of what he wants. Shuuji says that he’ll talk to his father and brother once he gets back, and it’s not entirely clear whether this will go well (personally, I’m willing to put more bets on his brother, whom I imagine is likely to be a victim of their father as much as Shuuji is), but the important part is that this will mean Shuuji asserting himself and what he wants back at his family, pursuing what he wants to do and being a leader figure in his own way, rather than doing things just because his family expects him to.

It took a much longer and much more painful way to get there, but Shuuji was able to come to a forward-thinking conclusion for himself not entirely unlike the one Jou reached at the end of Adventure, which I think is pretty neat.

Kaito and Dracmon, Miu and Syakomon

Kaito and Miu’s character stories are so intertwined that I honestly feel it would be better to combine their sections here (I also know Miu would probably hate this, so I give my deepest apologies to her). Of course, it probably goes without saying that they’re Survive’s parallels to Yamato and Takeru, in the form of an overprotective older brother and a younger sibling who wants to be more independent. However, Yamato and Takeru’s situation was heavily influenced by their family situation, which is very different from Kaito and Miu’s, resulting in some pretty significant differences.

Back in Adventure, Yamato and Takeru’s parents having divorced meant that the brothers only got to see each other once a year (Yamato jokingly compares it to Tanabata in 02 episode 17), and Takeru had gotten his parents to agree to let him join Yamato’s camp despite not even going to his school. Thus, Takeru was openly affectionate with his brother because he was happy to even have the chance to be with him at all, and Yamato was overprotective because he didn’t have very many opportunities to do much for Takeru to begin with. Both of them were still heavily hurt by the divorce and coping with it in ways that were not entirely dissimilar to each other; Yamato started judging his own self-worth by his ability to be independent and via comparisons to other people, and Takeru suppressing everything and pretending he had it together and everything was fine, even when it wasn’t. Yamato derived his self-worth from his overprotectiveness of Takeru because he was afraid of the idea of anyone providing that role better than him (such as Taichi), whereas Takeru’s insistence on independence came from his desire to avoid difficult things and to not hold everyone back.

In Kaito and Miu’s case, the two still live together, but the inciting incident that defined their current relationship was the fallout from Miu being targeted by a stalker and Kaito dealing with him violently, resulting in the family relocating to the countryside and both of them blaming themselves for it; Kaito blames himself for not sufficiently protecting Miu during the incident, whereas Miu blames herself for causing a burden on her family and everyone around her.

While Miu’s desire to be independent and tendency to retreat into escapism reflects Takeru’s, her way of reacting to it is almost the opposite; Takeru responded by trying to present himself as a responsible, mature kid who had everything together, whereas Miu shirks responsibility altogether and sinks herself into occult hobbies and mischief. (It’s for this reason that while Part 4 contains a scenario that greatly calls back to the Princess Mimi subplot from Adventure episode 25, it’s Miu who is the central character instead of Mimi’s actual counterpart Saki, who’s significantly less selfish.) On Kaito’s end, he becomes so obsessed with his role as Miu’s protector that it becomes more about him than it ever becomes about Miu. His description of her as a frail girl at the beginning of the game is horrendously off, and his hot-headedness is to the point where Miu calls him out for defaulting to solving things with violence and using her as a proxy for it. (Yamato did lose his emotional composure enough to start punching Taichi out in Adventure episode 9, but this wasn’t treated as something that would have normally happened if not for the immediate stress of the situation he was in, and his punch on Taichi in 02 episode 10 came from him knowing Taichi would understand what he was intending to do with it, but Kaito going as far as to even slap Miu in Part 9 makes it clear that it’s not really about her as much as it’s Kaito wanting his way in being her “protector”.)

Of course, Kaito’s abrasive nature masks the fact Kaito genuinely does want to be friendly and simply has a hard time expressing it, but when Miu dies in the Harmony route, the despair brings the worst out of him, and his more self-centered stake in the equation ends up taken to its logical conclusion. Having basically centered his entire life around Miu’s existence and his own relation to her, Kaito decides that the entire world can burn for all he cares despite it being very obvious Miu wouldn’t approve of that (and when everyone informs him of this fact, Kaito merely retorts that they don’t have the right to say they know what she would think, as if he would know any better). In the end, Kaito is only barely brought to his senses before being destroyed by what he helped create.

Things end up better for Kaito and Miu on the Moral and Truthful routes, although, interestingly, the problem is not completely solved over the course of the game; Kaito keeps lapsing into overprotective tendencies, but he admits to Takuma that this isn’t good and that he needs to start doing better. Even if Kaito wants to do better, this kind of habit is not going to go away overnight, so it’s important that he keep this in mind going forward, especially since the end of the Moral route has him remind his shadow that he’s not going to be a very good brother to Miu if he ignores the fact she can take care of herself. Miu, on her part, stops shirking responsibility and becomes more aware of her need to not cause more trouble for others; on top of her compassion winning out in Part 4 when she realizes how much her immaturity had been causing others pain, she also starts taking more proactive roles as each route progresses, and the Moral and Truthful routes have her be more willing to admit that she doesn’t want to have a bad relationship with her brother despite everything.

Dracumon has a much more put-together personality than Kaito and is key in getting him to chill and hold back instead of losing his temper, similar to how Kaito is aware that he needs to do better (thus, him completely succumbing to his own despair and selfishness results in him willingly throwing Dracumon out for the sake of more power). Syakomon and Miu are like-minded enough that they have the best relationship among most of the partner pairs in the game, but Syakomon is significantly more down-to-earth and pragmatic, and she serves as a reminder of the responsibility to others Miu knows she’s shirking when she goes off to do things at her own convenience.

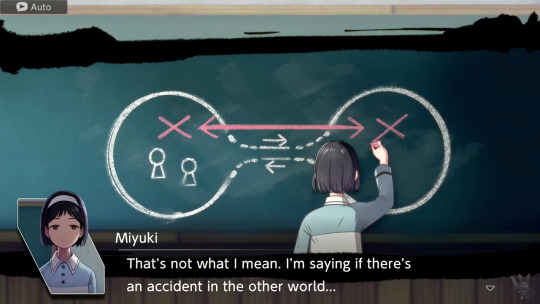

Miyuki and Renamon (”Haru”)

Fun fact: Due to Hikari’s natural sensitivity to Digital World-related phenomena and the fact she outright channels “the one who wishes for stability” (novel name: Homeostasis) in Adventure episode 45, quite a few Japanese fans have taken to calling her a “shrine maiden” (miko), basically comparing her to a Shinto priestess who helps communicate with the gods and convey their will...so, naturally, her Survive counterpart is an actual shrine maiden.

In fact, comparing Hikari and Miyuki is a little difficult, mainly due to the fact their contexts are so different -- the more detailed nuances of Hikari’s characterization didn’t start popping up until 02, and her comparatively short time in Adventure had her with a cold, so she wasn’t exactly in her most optimal condition. Thankfully, if we do retroactively reflect Hikari’s further characterization in 02 back on Adventure (especially since Miyuki seems to be closer to 02!Hikari’s age anyway), Miyuki is actually pretty similar to Hikari’s nature of being bright, assertive, insightful, very put-together, and incredibly selfless. (Also, the scene of her immediately going right to the blackboard and drawing out the relationship between the worlds brings to mind Hikari’s Jogress mockups in 02 episode 28 and her parallel worlds diagram in 02 episode 34.)

As for Miyuki herself, she is at least significantly more willing to be vocal and outspoken about her feelings instead of clamming up to dangerous levels and risking falling into despair about her own welfare like Hikari would (Adventure episode 48, 02 episodes 13 and 31). In addition, the fact she grew up as a “responsible older sister” instead of being in the shadow of an older brother like Taichi means she grew up with the expectation of having responsibility for Akiharu, and her independent streak seems to be in line with that (it’s commented that even despite Akiharu now being much older than her in age, she still seems to have it more together than him). However, being born to the Minase family meant she was trained as a shrine maiden from the very beginning, which ends up causing much more misfortune for her than it does Hikari; Hikari’s sensitivity abilities were more of a “factor” than anything, and her ordeal with Miyako in 02 episode 31 allowed her to assert herself in spite of her special position, but Miyuki understands her role as a shrine maiden to be a duty, which includes considering it her responsibility to sacrifice herself for others and the world if need be. And while Homeostasis ultimately borrowed Hikari’s body after negotiating with her and left after courteously explaining themself, the entity that ends up taking possession of Miyuki for the last few chapters of the game is...decidedly not as benevolent.

Takuma’s initial contact with the “real” Miyuki in Part 8 is very brief (fittingly, it’s during the chapter he has contact with the real world, like with Taichi’s brief visit and meeting with Hikari in Adventure episode 21), but it’s enough to convince him that she should be considered a trusted friend worth saving, which puts him a bit at odds with the others for a short time after his return. Unfortunately, Miyuki remains somewhat of a damsel-in-distress for most of the rest of the game, and in two of the four routes (Wrathful and Harmony) she unceremoniously dies when the route’s main antagonist absorbs her. On the flip side, however, she becomes extremely instrumental in saving everyone in the Moral and Truthful routes, and is also granted a way home and a much happier future with her brother.

Interestingly, the parallel continues with Miyuki’s partner Renamon having a very “complicated” relationship with her partner and with loyalties or morality in a similar way to Hikari’s partner Tailmon-- but in an inverted sense. Other than the obvious partnership reasons, Tailmon’s absolute loyalty to Hikari came from a past lifetime of bitterness gained from blackmail and abuse on Vamdemon’s part, so it’s only natural that she jumped ship at the opportunity and took the chance to be with someone who would treat her with love. (She did initially start off on a bit more of an abrasive note with the other Digimon, most notably setting Gomamon off with her attitude in Adventure episode 45, but she eventually settled in.) Renamon is the opposite; her absolute loyalty to Miyuki and desire to be the one to make her happy (even to the point of taking the form of someone she hates) results in her stooping as low as trickery, betrayal, and submitting herself to an abusive master just for the chance to get Miyuki back (and, more selfishly, to prove that her bond with Miyuki means something, in the sense that she can’t stand the idea of anyone being more important to Miyuki than herself). It's an interesting contrast where, in both cases, the arguably most morally upright person in the group has a partner who ends up most closely associated with questionable morality, but it also goes to show you that even the best of intentions can end up with very bad results when sufficiently pointed in the wrong direction.

Professor (Akiharu)

Every Digimon series needs a designated infodump character to unpack what’s going on with the worldbuilding and all, and back in Adventure Koushirou was the main bearer of this role -- in fact, he was so important that he ended up constantly showing up in 02 despite not technically being a part of the advertised main cast. At first, it seems as if the Professor really is mostly just this, and it’s initially even questionable how helpful of one he’ll be when it seems like he’s died at the end of Part 3. But not only does the Professor return to provide more info behind what’s going on, he also ends up becoming instrumental to determining the difference between the endings, because whether he’s present or not and how much he’s learned become the biggest influencing factors on the outcome. (The Harmony route involves the gate being opened much less aggressively than in the Wrathful route, but it’s implied things still had a worse outcome than they did in the Truthful route because the Professor wasn’t able to be there anymore to give any guidance, and the Moral route has everyone seal off the gate because him never uncovering the truth behind the Master meant they destroyed it and thus the system that gave the boundary between worlds any stability.)

The Truthful route happens thanks to the chain reaction of Ryo saving Shuuji and Shuuji becoming the Professor’s assistant, allowing him to more effectively dig up the truth regarding the Four Holy Beasts, the Master, and Haruchika -- hence why it’s called the “truthful” route, not simply in terms of being a “true ending”, but also in terms of it being the ending where the truth behind it all was revealed. Through flashbacks and eventually some outright statements, we learn that as even as a kid, Akiharu actually had quite a bit in common with Koushirou, in terms of being timid and deferential yet bursting with intellectual curiosity and a desire to know more. Back in Adventure, Koushirou managed to uncover some very important things about the Digital World thanks to the fact he actively pursued anything he was interested in, and while Akiharu spending his life studying the Kemonogami might initially seem to be his way of coping with the traumatic loss of his sister and memories, he tells Garurumon in the Truthful route that it was simply his encounter with him that inspired him to learn more and teach others.

The ending of the Truthful route draws parallels between the siblings Haruchika and Yukiha with their descendants Haru and Miyuki, but their situations are reversed; Haruchika was the one “abandoned” by his sister, whereas Miyuki was “abandoned” back in the Digital World when she sent her brother back, and thus the Master attempts to claim Miyuki as someone who should sympathize with him only to find that she bears absolutely none of the malice he does. And like Yukiha, Akiharu doesn’t give up on finding his sibling again and eventually manages to do so, despite going through trauma and memory loss (and some scorn from the scientific community) to get there. On the flip side, Garurumon ends up bearing the emotional pain of being left behind, but in the Moral and Truthful routes he can’t bring himself to hold the grudge for too long once it becomes clear Akiharu really didn’t mean for that to happen. In the end, despite all the trouble that happened between Akiharu, Miyuki, Garurumon, and Renamon, none of them were able to hold onto their grudges, and that’s what eventually allows them to save Haruchika from his own.

Haruchika

You might be wondering, wait, what, this guy? Well, you see, in the Truthful route we find out that he was a sacrifice for others to have power, and he decided to take out his feelings of betrayal out on the world and bring it down with him. Now how does that correlate to anything in Adventure --

-- oh, okay.

I’m sure a lot of Adventure fans who finished the Truthful route were probably at least able to figure out the parallel overall, but inspecting it closely reveals there’s even more than you might think -- Haruchika is deliberately drawn as a parallel to Akiharu in a sort of Survive equivalent to a “fallen Chosen Child”, and his laments rather parallel Apocalymon’s “we wanted to live and speak of friendship, justice, and love!” And in the Moral route version of things, the Master forces the kids to go through trials of overcoming their darkest feelings and reaffirming how far they’ve come, quite similar to the reaffirmations in Adventure episode 53.

Fortunately for Haruchika, his much deeper contextual relation to Survive’s story and themes (and therefore sympathetic qualities) allow him to be saved and to pass on properly with Yukiha, which certainly beats going out in a failed suicide bombing. Adventure, as a sort of pioneer for Digimon works thereafter, had Apocalymon serve as the “inhibitor of evolution” compared to Adventure’s “story of evolution”, but Survive, which spends more time examining what a Digimon partner even is in the first place, thus has Haruchika represent more of a challenge to what the Survive kids learn to find and what ultimately saves Haruchika himself in the end: as the theme song says, turning hatred into love. Haruchika himself is said to be the first to have realized that bonds between humans and Digimon made each other stronger -- basically being the inventor of Digimon partnerships in this universe -- only for him to end up succmbing to his own hatred and the malice of the world.

Also, when you really think about it, the Master is the closest thing you can say to entities that “chose” the kids as the Survive equivalent of Chosen Children -- at least, in the sense that their distortions dragged the kids into the Digimon world in order to prey on them. Homeostasis and the Agents were still guilty of dragging Adventure’s Chosen Children into the Digital World and not really giving them good explanations, but Homeostasis rather courteously explains in Adventure episode 45 that they were doing it out of desperation for lack of many other options. However, Homeostasis also made it clear that they didn’t have many abilities on their own besides housekeeping, and that the kids would have to be the one to figure the rest out on their own (the novels clarify that it’s really nothing more than a security system), whereas the Master does pose himself in a deity-like position and even has the entire stability of the Digital World depend on him -- it’s just that they’re also quite the opposite of cooperative. So in both cases, regardless of the initial circumstances, the groups involved had to solve the problem on their own will.

192 notes

·

View notes

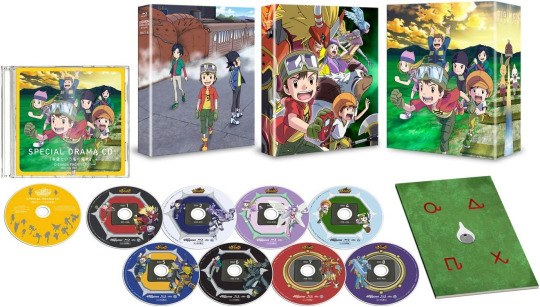

Photo

So if you’ve known Digimon Adventure for long enough, you’ll know that it has some very strict color-coding for its characters thanks to the Crests: Taichi with orange, Yamato with blue, Sora with red, Koushirou with purple, Mimi with green, Jou with grey, Takeru with yellow, and Hikari with pink. There’s also a very strict “order” of characters, which is exactly the order above (it’s the order in which we saw their Digimon’s first evolution, and in the second ED). The franchise has followed this with strict consistency for almost the entire time since Adventure’s airing (it took until a little after 02 for the order to completely solidify, but after that it basically hasn’t budged). For Tamers fans, the order for the main three characters has also been consistent -- although there are rare exceptions, it’s pretty much always Takato, Jian, and Ruki in that order, associated with their D-Ark colors red, green, and blue respectively.

On the flip side, 02 and Frontier have been...decidedly less straightforward. Things like color coding and character ordering probably don’t matter much to the average viewer, but for fanartists (like @digitalgate02 and @demonoflight, who graciously assisted in helping me write the rest of this post), this can easily drive a person absolutely nuts. However, thanks to DigiFes 2022 and other surrounding events, these questions have finally been cleared up!...Maybe.

Let’s take a look at the history of 02 and Frontier’s color handling and ordering (with some bonus series thrown in)!

02

So as I said earlier, generally speaking, the Adventure order and coloring has been very straightforward, and when you involve Adventure and 02 in a group of twelve, the order for that has been consistent for the most part after 02′s airing: Taichi, Yamato, Sora, Koushirou, Mimi, Jou, Takeru, Hikari, Daisuke, Ken, Miyako, Iori. (This ordering has basically all been all but completely solidified on the Kizuna website and in most Kizuna promotional materials thereof.) That said, things get a little more complicated once we talk about the 02 group specifically, especially because of Ken’s unusual position -- usually “latecomer party members” are added on at the end, but Ken ends up in a right-hand man position to Daisuke in terms of the story, so it feels a little awkward to tack him on in the end like that. If you go by rough order of “evolution introduction” for the series, that implies a Daisuke-Miyako-Iori-Takeru-Hikari-Ken order, but other materials have offered a “Jogress order” (Daisuke-Ken-Miyako-Hikari-Iori-Takeru) or “original order but with Ken moved up” (Daisuke-Ken-Miyako-Iori-Takeru-Hikari).

Things get even trickier when you get to figuring out their image colors. You could try doing the Crest colors (orange and blue for Daisuke, pink...? for Ken, red and green for Miyako, purple and grey for Iori, yellow for Takeru, and pink for Hikari). But not only does this cause overlap with Ken and Hikari both having pink of some kind, it’s also just not very good for design and merch, due to the lopsided nature of three of its members having two colors while the others have three (the Kizuna website attempts it, but only on the character square borders).

The seemlingly easiest and most straightforward one to use is the D-3 colors (blue for Daisuke, black/grey for Ken, red for Miyako, yellow for Iori, green for Takeru, pink for Hikari), and we do have quite a bit of precedent on this one, most notably in 02′s second ED. Unfortunately, this color scheme comes with one major issue: grey isn’t exactly a very easy color to use in design, especially for merch. (Jou merchandise struggles with this issue a lot, and it’s really only offset by the fact he’s surrounded by a whole seven others to make the impact less noticeable, plus the fact it’s explicitly a light grey, unlike Ken’s dark grey and black D-3.) Ken’s D-3 remaining black was a very important symbol of his penance in-series, but it makes merchandise making a bit tricky. It also is not very easy to use for shiny glowy things, and even this same ED struggles with that:

...yeah. (White is never used for Ken anywhere else.)

And then there’s the fact Ken’s Wormmon is associated with being the “green” side of Paildramon, and Daisuke and Ken’s Jogress D-3 combo is blue and green...but because the other combo colors (red/white and yellow/white) aren’t really ones that are easy to make hard matchups with, it’s still hard to say that there was any hard association with green and Ken back in 02, especially since that makes it more complicated with Takeru.

Even Kizuna struggled with this for a bit. The movie shows Takeru with a yellow phone case, in a context where the other five members of the 02 group have cases matching their original D-3s, but in all other contexts -- promotional art, merchandise, the card game, the character song album -- it’s back to green, matching with his D-3. But there is merch that associates Takeru with yellow, his Crest color, overlapping him with Iori...and giving Ken green. Generally speaking, it’s understandable that any context with all twelve Tokyo Chosen Children will have to have a color overlap somewhere, but Takeru particularly sticks out as one they don’t really know what to do with.

(Note that the card game’s backing colors don’t apply; the card game’s mechanics are tied to its own set colors, which means that characters are placed in there for reasons closer to their Digimon’s archetype than their own original series image colors.)

However, starting with the Kizuna character song albums (technically also the concurrently-released Digimon Stitches, but that one also had a contradictory palette in the same set), it seems like recent merch (especially in relation to the upcoming movie) is finally consistent about color -- but what’s interesting is that Takeru is now orange. That was never used in 02. That wasn’t even used up until 2021!

The theme behind the new colors seems to be, quite simply, their partners’ colors (V-mon’s blue, Wormmon’s green, Hawkmon’s red, Armadimon’s yellow, Patamon’s orange, and either the pink from Tailmon’s ears or Angewomon). This does seem to be in line with the angle taken in both Kizuna and the new movie that this group is rather unusually close with their partners, possibly even more so than their seniors. The benefit of this color scheme is that, with there being a consistent baseline for all six of them, there’s now proper justification for Ken being associated with green, while also not putting Takeru in an awkward position.

These colors were used for the official DigiFes 2022 penlight, which explicitly lists the following colors as the kids’ “image colors”: "light blue" for Daisuke, "red" for Miyako, "yellow" for Iori, "orange" for Takeru, "light pink" for Hikari, and "green" for Ken.

Perhaps acknowledging the truly chaotic nature of this issue (probably fitting when this group is concerned), the Karatez collab firmly, undeniably associates these colors with the original 02 kids instead of just the Kizuna-era ones, but also strings a bunch of other colors here and there to reference their other associations: Daisuke’s orange glasses and shoes (Courage and Friendship), Ken’s black shirt (D-3), Wormmon’s green maracas and blue band (Jogress with Daisuke and V-mon), Miyako’s red shoes and green guitar (Love and Purity), Iori’s purple guitar and grey shoes (Knowledge and Faith), Armadimon’s orange tambourine and green band (Jogress with Takeru and Patamon), Takeru’s yellow shoes (Hope), Hikari’s pink keytar and shoes (D-3 and shoes), and Tailmon’s red keytar (Jogress with Miyako and Hawkmon). That’s basically about all you can cram in there at once. Whew!

(As an aside, some of Miyako’s merch tends to toe dangerously close to purple at times, including in this very collab, but it’s probably intended to be pushing the boundary of what can be considered “red” as far as possible; her smartphone case has some noticeably purple tones, probably to prevent it from overlapping too much with Sora’s red.)

It is still probably a bit weird that this color scheme is obviously retroactive, since it wasn’t ever in 02 itself or anywhere near its airing, but it’s nice to finally have something consistent to work with for once after all these years. Will future things continue to maintain this? Hopefully. Probably.

As for ordering, unfortunately, this is still fluctuating, because even the same sets of merch can’t seem to decide whether Ken is second or last. It does seem like most merch so far has been favoring the Daisuke-Ken-Miyako-Iori-Takeru-Hikari ordering, putting Ken next to Daisuke for obvious reasons, which the movie website also supports -- and the added benefit of this ordering is that if you put them in two rows or columns of three (which is done quite often), the Jogress pairs will still be next to each other. So for the most part, I’d say it’s safe to say things have mostly settled on that one.

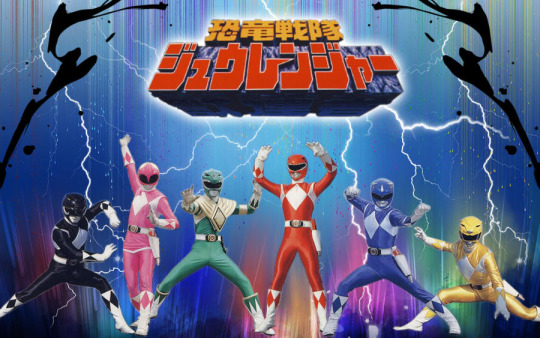

Frontier

Frontier is explicitly based off Super Sentai, so that means a lot of its visual compositions with the cast are focused on Takuya in the center. However, unlike Sentai, Frontier doesn’t really have ordered roll calls. And while the OP gives you a Takuya-Izumi-Junpei-Tomoki-Kouji order, putting Kouji last feels a bit off considering we pretty much all know he ends up being Takuya’s lancer character for the series (and unlike Ken, we know this very early in the series). Besides, if you watch Sentai, that’s pretty much just how it goes. The first ED offers multiple different orders, so it’s confusing. (And on one hand, it’s possible to make an argument that it’s refreshing that the orders seem malleable, but on the other hand, this is jarring since ordering is a staple of Sentai.)

Also unlike Sentai, there hasn’t been a lot of consistency with the colors, which is especially strange considering that producer Seki explicitly mentioned that Izumi should be associated with pink due to Sentai’s precedent. In fact, a lot of older materials do seem to want to associate Izumi with pink specifically:

But as you can see, there's already some contradictions in regards to color associations, because we can't tell if Takuya's supposed to be orange or red (Sentai associations would suggest red), whether Junpei should be blue or yellow, or whether Tomoki should be light blue or green...and to make things even more complicated, the D-Scanners all have two colors each (and that’s in base colors, because Takuya and Kouji get new ones later).

And, unfortunately, you shouldn’t expect the elemental symbols to help you either, because not only does Kouji being associated with pure white pose similar problems to Ken having black or dark grey, the combo of red/white/light blue/pink/dark blue/purple also isn't really very balanced in terms of design (no yellows...).

While Frontier didn’t get a consistent stream of merch to be contradictory per se, it turns out that by the time we get to the 20th anniversary stuff, we still don’t have a consistent answer!

(ノ°Д°)ノ︵ ┻━┻

Well, okay, it’s not that bad. The same penlights that doubled down on the new coloring for the 02 kids also offered some official image colors for the Frontier kids as well: “orange-red" for Takuya, "blue" for Kouji, "light green" for Tomoki, "purple" for Izumi, "orange-yellow" for Junpei, and "light grey" for Kouichi. Keeping in mind that the colors have such specific names mainly to not give them too much overlap with the 02 kids’, it’s probably better to consider it as red for Takuya, blue for Kouji, lavender for Izumi, yellow for Junpei, green for Tomoki, and purple-tinted grey for Kouichi. In addition, there’s a consistent aspect about this: they correspond to the grip colors on the D-Scanners (the original ones in the case of Takuya and Kouji), so we have a baseline too!

Kouichi does seem to consistently show an angle of wanting to use proper grey but not really wanting to ruin design composition, so some obvious purple tints are put on it to make it blend nicer with the other colors. This is probably something that’s only possible because unlike with Ken, Kouichi ends up actively embracing his association with darkness, which has a purple elemental symbol and has been associated with “darkness” to some degree in the past (the current card game uses it for darkness-aligned cards even besides Kouichi). On the flip side, the bonus about acknowledging Izumi as having at least some kind of purple tinting to it means much better consistency with Izumi/Fairymon/Shutumon’s coloring.

As for the ordering...well, still, good luck. However, I personally feel that merch lines have been more likely to depict the Takuya-Kouji-Izumi-Junpei-Tomoki-Kouichi order, and if you have to ask me, I personally prefer this ordering as well because it makes a nice alternation between the Hyper Spirit Evolutions (fire/wind/ice and light/thunder/darkness).

Bonus

It seems like it’s always the group ensemble things that want to drive us nuts, because other than having this problem again, that’s what Appmon also has in common with 02 and Frontier. The good thing is that there does seem to be some kind of baseline -- usually Haru-Eri-Astra-Rei-Yuujin seems to be somewhat of a followed order, and Yuujin isn’t really put aggressively in the second position like Ken is because his looming presence in the series isn’t nearly as conspicuous. In addition, the Appli Drive covers also seem to be consistent between the original model and the Duo -- red for Haru, blue for Eri, yellow for Astra, and black/grey for Rei, and this seems to be consistent with their Buddy coloring as well. So one could probably extrapolate and decide that purple for Yuujin would work based on his Duo color and Offmon...but then the second OP decides to mess with you at the last minute.

Of course, the reason why is obvious, and it’s possible it really is just for that OP -- again, grey/black tends to be a hard color to work with, and Yuujin really doesn’t seem to fit the image of purple himself (that’s more Offmon). Sadly, Appmon never lasted long enough to get merch runs to really lock down on any of this, so it’s more “vague” than “contradictory”. But it is at least interesting that Haru is consistently associated with red, despite his temperament completely lacking the tropes associated with the color and the consistent underlying question of whether he’s suitable to be a “protagonist” or not.

But hopefully, this won’t continue to be an issue in the fu--

OH, COME ON

137 notes

·

View notes

Note

Seems like someone translated the now unavailable stage reading from DigiFes2022 and i'm shocked about some things like, the twins not being all lovely around each other (a very common fanbase's interpretation/guess) and how Kouichi does not seem to be a shy (??) person like Ken (another fanbase guess regarding him)

Any thoughts? 😗

There is so much to unpack here. So much. So, so, so much. I thought I was going to answer this quickly, but then this post got too long because I had so much to say, so I'm going to tuck the rest under the cut, but my goodness. I'm actually offended this is from a "vanishable" stage reading (and that the official stance is even that the contents are meant to be disposable and not taken as canon -- to hell with that, material like this, let alone for Frontier, is too valuable to let go of). I don't know about other people, but this checked off all the boxes for things I wanted to see addressed or confirmed, moreso than even The Train Called Hope from 2019 (which I did still like, but to be honest, this one felt more like it was "at home" in a sense).