#showing

Text

Showing is really exhausting now. And it only lasts 15–20 minutes. I guess I’m getting old…

Anyone else find showers/baths tiring?

#bathing#showing#baths#these are exhausting imo#feel free to share your thoughts#feel free to share/reblog

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

꧁★꧂

#anime#anime girl#anime boy#pink#star#abstract#love#knowing#growing#showing#sewing#hoeing#glowing#flowing#bestowing#rhyming#photoshop#digital collage#flickr#oldweb#old web#cute#kawaii#2007

36 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Children have never been very good at listening to their elders, but they have never failed to imitate them.

James Baldwin

#be the change#actions#deeds#behavior#example#guidance#parenthood#education#learning#showing#mirroring#growth#maturing#feeling#thinking#question#understanding#society#humanity#respect#love

134 notes

·

View notes

Text

Romans 12:10 (ESV) -

Love one another with brotherly affection. Outdo one another in showing honor.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Writing Tips: Understanding Beats, Showing, Telling, Pacing, And Their Relationships

Beat:

A unit of action, emotion, or pause within a scene, where something significant happens, a character reacts, or a shift occurs.

Beats are the building blocks that shape the overall flow of a story.

Beats consist of narration that are usually either showing or telling.

Showing (Dramatization):

Presenting details, emotions, thoughts, and sensations to allow readers to experience the story.

Slows down the narrative by immersing readers in vivid, descriptive scenes.

Example: Instead of stating a character is sad, describe their trembling lip, tear-filled eyes, and a heavy sigh.

Telling (Summary):

Conveying information efficiently, summarizing events or details.

Speeds up the narrative by providing quick, concise information.

Example: Stating a character's emotional state directly, such as "She felt joy."

Pacing:

The rhythm at which a story unfolds.

Effective pacing involves a strategic combination of showing and telling.

Alternating between high action low emotion beats and high emotion low action beats creates a dynamic pace, prevents monotony.

This is part of my Writing Tips series. I publish writing tips to this blog.

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

milo and ponzu were show dogs today! reserve best male and reserve best female. not bad considering silkens had one of the biggest entries today! :)

200 notes

·

View notes

Text

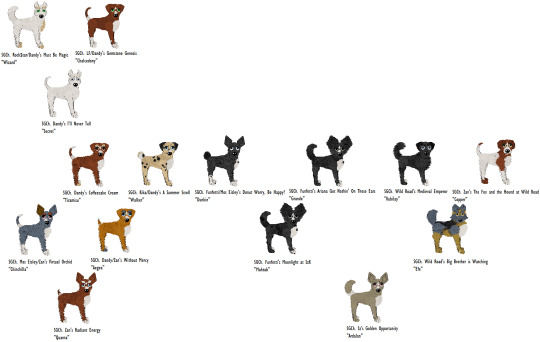

A little SGCh. tamsin litter I bred between two of my dogz:

SGCh. Zan's Radiant Energy X SGCh. Sz's Golden Opportunity

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Show and Tell

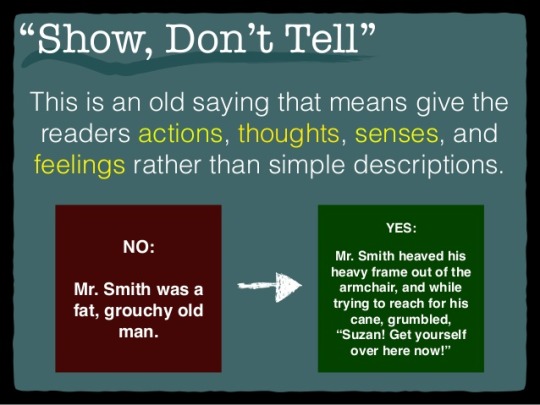

There's an age-old adage taught to new writers: "Show, Don't Tell!"

Some take it to mean they should remove all talking, because talking is people telling each other things. Some take it to mean you can't have anything happen off-screen, you have to show absolutely everything. Some say all text is telling, because it's not an image. Some say all prose is showing, because the reader has to imagine it one way or another.

...Phew!

There are hundreds of ways people interpret this phrase, and unless they understand it correctly, writers can quickly find that it's just not feasible to write in such a way. There are many who have concluded that "Show, Don't Tell" is simply bad advice and should not be followed and offers writers nothing.

Why are there so many ideas on what this simple phrase means? Is it good, or should it be discarded from writing vernacular? What does it mean to "show"? And what does it mean to "tell"?

To get to the heart of what this advice is talking about, I give you a simple example:

She looked rich.

Is this piece of prose "telling" us something or "showing" us something?

Well, let's try visualising it. She could have fancy hoop earrings. Or maybe glittering diamonds around her neck. A long flowing white gown? Maybe she's more of a modern celebrity type, in a tailored suit, slicked-back hair and shades and pouting botoxed lips.

Hrm... the text didn't really narrow that down for us did it? She could look like anything. It is telling us that we would conclude the woman is rich based on what we see. But it doesn't show us what we actually see. So... we could be seeing anything.

Consider the difference if instead of text, someone gave us a photo of a rich woman.

This is Salma Hayek. She's a woman. She's rich. But in this photo alone, it's not obvious that she is rich. She doesn't look rich here. If someone told us "there once was a woman who looked rich," we probably wouldn't come up with this kind of image in our minds.

This is showing us something of course; it's an image. But it's not showing us something that is likely to have us conclude that "she is rich."

Now if we tweak the image a bit...

Okay, so sparkly jewels and an expensive coat is probably more in the ballpark. She may not actually be rich--those diamonds may be stolen, or fakes. This image doesn't tell us any hard facts regarding her finances.

But I put it to you that she looks rich, at least. And I'd say that most people would come to that conclusion when shown this image.

Now to put it in terms of prose...

Diamonds sparkled about her neck and hands, and a long faux-fur coat draped over her shoulders, swaying as she walked.

This isn't described to the tiniest detail; there are still aspects we would fill in with our imagination like height, dress, what the specific jewelry looks like. But when we visualise this woman we know for sure that she's wearing diamonds and a faux-fur coat. And we could easily conclude that "she looks rich."

That's the difference between telling and showing. One skips to the conclusion, the other lets us work it out for ourselves.

But... who cares?

Either way, the reader is going to get to the same place: she looks rich. The difference is the journey taken to get there.

If someone told us "Aliens have landed in London," we might not believe them. Even if we know them well, and trust them with our lives, we might think they're pulling our leg or it's the start of a joke.

We might ask, "How do you know that? Why should I believe you?"

If we were in London and saw a UFO slowly float down from space, plop down in Trafalgar Square, and a little green man popped his head out and said "Hi"... we'd be a lot more likely to believe that "Aliens have landed in London."

Why? Because we saw it with our own eyes. The idea that aliens did indeed land came from our own brains based on our own experience. We drew our own conclusions.

That's the advantage "showing" has over "telling."

The writer may want the reader to know a particular thing, may want to tell them a fact, may want to just copy-paste that detail from their outline into the prose and be done with it. They want to simply tell the reader the thing they want the reader to know.

But if they can show the reader something, and let them draw their own conclusions... that's a lot closer to how their brain works in real life. We experience things in the real world, sense things, see things... process what we've experienced, internalise what's true and what's not... and conclude things from that experience.

If we give the reader the chance to do the same thing while reading our stories, they will experience those stories. They will feel immersed in our world, as if they really saw and experienced those things themselves--because we're getting their brains to work the same way it would if it wa all real.

This is what immersion is all about. Making it feel like they are in the scene with the characters, witnessing everything go down!

On top of that, if we're using a viewpoint character, we're experiencing what they are experiencing. They are seeing "Diamonds sparkled about her neck and hands, and a long faux-fur coat draped over her shoulders." And we are seeing it. They are experiencing the world around them, and we're experiencing it with them.

We're relating to the character by having the same experience they are having! We're simulating how they think. We're seeing them like us: a real human being. (Or non-human being at least.)

So it immerses further, by allowing us to identify with the viewpoint character at a deeper level.

Does this mean everything has to happen on-screen?

Does everything have to witnessed by the viewpoint character and the reader for it to be part of the story? No.

"The Princess gave birth to a son!" the maid cried.

This is dialogue. But... isn't that telling? Shouldn't we write the birth itself into the story, to show that to the reader?

Not necessarily. If the viewpoint character isn't the doctor or the prince or something, it could be highly inappropriate for him to pop his head into the room while the Princess is giving birth, just so the reader can look over his shoulder!

It's perfectly reasonable that a viewpoint character would find things out by being told verbally, or by a written note, or whatever else makes sense--as opposed to witnessing everything to do with the story.

You couldn't have them witness the birth/creation of every character they meet just to accept that they exist, after all. And if they live in the US, it's not necessarily going to be feasible to fly them over to London to see those aliens and then back again so the rest of the story can play out.

This isn't about making everything happen in front of the reader. It's about focusing on the story, showing the experience of the viewpoint character (or if there's an omniscient narrator, what they "experience"). As opposed to telling the reader about the story in a summary.

Dialogue--even exposition like "The Princess gave birth to a son!"--is literally what happened. The maid came running in, and shouted those words, and the viewpoint character heard it. We are being shown what happened in the story.

Compare this to the writer telling the reader. That wouldn't be part of the story. It would be more like "Hey, GRRM here. Princess gave birth--just thought I'd let you know. Anyway, back to blood, grit, and drama."

The story is on hold while the writer tells us about the story. Definitely not as immersive as a character within the story telling another character within the story and the reader just overhearing it.

This is how to make exposition more immersive and enjoyable to read: have the reader overhear, observe, and pick up on things almost "by accident." The key there is to orchestrate those accidents.

There are many ways of getting information to the reader under the guise of it all happening naturally as the story unfolds. Even putting things straight into the narration, but dressing it up as the thoughts of the viewpoint character... as prompted by something they saw or experienced.

The below includes a narrated thought, for example.

I fell to my knees, tears in my eyes. It was a miracle!

This is what the viewpoint character thought. That happened. It is part of the story.

So you can keep things in the realm of the story, even when you're pretty directly feeding them what you want them to know. You can "tell" them without telling them--without them realising it.

Now, is there no excuse for ever outright telling the reader something? Is telling banned?

Not quite.

For the above reasons, it's generally preferable to show things and let the reader experience them most of the time. And to find excuses for them to experience things. But that's not always possible.

And for a particular section it may not be your intention for it to be immersive anyway, so do whatever feels right. The important thing is, understand that "showing" is a thing you can do. It's up to you to figure out how you want to use that understanding.

So what does "Show, Don't Tell" mean?

What is "telling"? The reader learning things by the narrator telling them what they want them to conclude.

What is "showing"? The reader learning things by experiencing the story and drawing their own conclusions.

That's the sweet spot. Keep the reader "in the pocket," keep them immersed and in the flow of seeing the story unfold, and let them figure stuff out themselves, like grown-ups.

You might say it this way:

Writers, show readers the story. Don't tell them about the story.

Instead of someone giving you a summary of "this really cool movie I saw over summer break. And then this happened, and then that happened, and [explosion noise] woohoo!" ...Just let them watch the movie!

Aren't they just the wrong words, then?

Some choose to rewrite the phrase using different words. Which is fine, if it helps them remember what it means. But I think the original words work just fine, too.

The problem is, people assume certain definitions. But there are other perfectly fine definitions we use in everyday speech too. If you reach for "show: to present an image," that takes a bit of mind-bending to get it to fit. But if you asked someone to "show me how to make a cup of tea," you'd expect them to demonstrate, to make the tea in front of you, in a way you can learn from.

And "tell me how to make a cup of tea" would probably get you a list of instructions with no demonstration. An explanation of how to carry out the task. That could be given as text on a piece of paper, or said out loud... that doesn't matter to being told how to do it.

A common reformulation of the phrase is "demonstrate, don't explain." Or "illustrate, don't summarise."

But, as "tell" can mean "communicate information," it's a synonym for those words anyway. And "show" can mean "allow (a quality or emotion) to be perceived; demonstrate or prove," so that's a synonym as well.

So what's the point of "Show, don't tell"?

"Show, Don't Tell" is indicating a direction to head towards if you want the story to be more engaging, and immersive. It reminds us:

Being told a room has no oxygen in it is less visceral than seeing a human being in that room struggling to breathe.

"The eiffel tower is 330 metres tall" gets a less emotional reaction than standing beneath it and looking up.

It lets new writers know that it's actually possible to show things to the reader instead of just telling them "She looked rich."

Some writers don't know that they can show things, that showing something can teach the reader what they need to know just as well as telling them. But also be part of the story and enjoyable to read.

"Show, Don't Tell" is a valuable lesson to learn, and to teach others. Just remember to teach it by showing examples, not just telling them the phrase and leaving them to it.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

#katie leigh#baby bump#glowing#showing#growing#pregblr#preggie#pregnancy#pregnant#pregnant women#pregnantbelly

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Joan Pradells compares !

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

I have been doing some rereading (while sick and have no voice) of an older book my mother had gotten me a while back. She got it for me to help me write. In that, there is one thing that really stuck with me, that has helped me a lot.

I had never thought of this before in this context. The difference between telling the reader and showing the reader. I understand this isn't for every single line, ever, in a story. However, it should be considered most of the time.

Most readers are using their mind as a canvas or movie reel. Telling them something happened doesn't paint a full picture. Showing them makes it clearer and in a way, gives them control over what they see. The mind doesn't always listen, but it helps. Lol

Anyway, just my two cents for today.

#welcome to my ted talk#im sick and nothing else to do but read and write#when im not sleeping#writing#fanfic writing#changing perspectives#worth it#in the end#showing#instead of telling

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Titus 3:2 (NKJV) -

to speak evil of no one, to be peaceable, gentle, showing all humility to all men.

55 notes

·

View notes