#sinister centenary

Text

Christopher Lee: A Sinister Centenary - Number 8

Welcome to Christopher Lee: A Sinister Centenary! Over the course of May, I will be counting down My Top 31 Favorite Performances by my favorite actor, the late, great Sir Christopher Lee, in honor of his 100th Birthday. Although this fine actor left us a few years ago, his legacy endures, and this countdown is a tribute to said legacy!

Today’s Subject, My 8th Favorite Christopher Lee Performance: King Haggard, from The Last Unicorn.

In the 1980s, classical fantasy films were pretty popular. Movies like “Labyrinth,” “Legend,” and “Dragonslayer” were all over the place, and most of these movies remain cult classics (if not outright “classics”) to this day. There was a certain charm to fantasy of the 1980s, both during that time and now, when looking back, that you just don’t find in other movies of a similar sort. One of the earliest of these 80s fantasy flicks, and one of my personal favorites, is 1982’s “The Last Unicorn.”

Based on the novel by Peter S. Beagle (who also wrote the screenplay, and had a hand in casting), this movie was a theatrical release by Rankin/Bass. I mentioned them before on the very first entry of the countdown, as the people who made classic Christmas specials like “The Year Without a Santa Claus” and “Frosty the Snowman.” They actually released several classic fantasy pieces, too, most of which were TV films…but “The Last Unicorn” was a rare cinematic production. Typical of Rankin/Bass, the movie boasts an all-star cast, prime among them Christopher Lee as the main antagonist: the mysterious and menacing King Haggard.

The story of “The Last Unicorn” focuses on the titular Unicorn, who has learned she may be the last of her kind. Deciding to find out if this is true, she goes on an adventure to try and find the other Unicorns. She soon learns that a creature called the Red Bull (which does NOT give you wings, for the record) has captured all the unicorns, and hidden them somewhere under the command of the tyrannical Haggard. Haggard is a perennially miserable figure: it’s revealed that, for unknown reasons (at least in the film), he has essentially lost all zest for life. Nothing makes him happy: he desperately seeks anything that can give him the smallest amount of joy, but nothing works.

Nothing…but the Unicorns. Haggard has discovered that only the enchanting presence of the Unicorns gives him pleasure of any kind, and makes him feel, in his own words, “truly young again, in spite of himself.” He quickly comes to suspect that the “Lady Amalthea” who visits him (the Unicorn, disguised as a human) is the one missing unicorn he has never been able to track down, and tries to figure out a way to get her to reveal herself, and thus capture her, too.

Lee claimed that Haggard was one of his favorite roles. He loved it so much that he volunteered to do the German dub of the film (Lee spoke fluent German), just because he enjoyed the character so much. He likened the character to Shakespeare’s King Lear; I have to admit, a while back, I had no idea what he meant by that. Nowadays, I can KIND OF see it. Shakespearean allusions aside, however, Lee’s performance is largely what makes Haggard a compelling villain: he, of course, is able to bring a sense of command and sinister power to the character. That’s honestly to be expected. But what I love most about Haggard are his softer moments. This character so easily could have been depicted as a cartoonish, crotchety figure: Just some old sourpuss who hates everyone and who everyone hates – a slightly more evil Eustace from Courage the Cowardly Dog, if you will.

That’s not what Lee does: you don’t really know WHY Haggard is so utterly depressed throughout the movie, but you really do feel “depression” is the word for it. There are moments where you feel sort of sorry for him, because the overwhelming sadness is so palpable. The way he talks about the Unicorns is almost touching; he sees them like angels, saviors to his eternal dreariness. At the same time, however, you never forget he’s the bad guy, his moods swinging rapidly, giving him a sense of leaning heavily towards total madness. He also has some of my favorite, most quotable lines any Lee character has ever had. Just for one example: “I can wait. The end will be the same: I can wait.”

A cartoon baddy played by Christopher Lee just gave you one of the best quotes about patience you’ll ever hear. I love this movie. ^^

The time has come to move into the final week of the countdown. Tomorrow, I present my choice for Number 7!

#christopher lee#sinister centenary#happy birthday christopher lee#top 31 christopher lee performances#may special#best#favorites#list#countdown#number 8#king haggard#haggard#the last unicorn#last unicorn#rankin/bass

49 notes

·

View notes

Note

i know that mushroom is seen as 'enemy of truth' by both green and black, because the things he talks about both aegon and rhaenyra, nobody wants to believe, but perhaps it is in him that there is more truth than in others. I mean, if there was a historical book about the events of asoaif and the moon boy narrated them, we would probably think it was exaggerated and that this would never happen, that his accounts involve many sinister things, but hey we have incest of twins, wargs, betrayal, treason, fratricide, conspiracies beyond account in the main story, hell, we even have a centenary man half fused to a tree in a cave, sounds absurd, but it's there, why is it so hard to believe that sara snow exists? mushroom didn't go north with the manderlys? manderlys are vassals of the starks, it would be impossible for him to have met her personally at some point? I think the fandom needs to be more open-minded and see beyond favoritism, it's like they don't know the main saga, where similar things, however absurd they were, really happened

Did you know that:

Sara Snow's story was among the content George R. R. Martin initially wrote for The World of Ice and Fire (2014) but was cut from the book due to space constraints. Sara was later mentioned in Fire & Blood (2018) and The Rise of the Dragon (2022).

Yeah, GRRM had the opportunity to erase Sara Snow from the books once and for all, since she was cut from The World of Ice and Fire (2014), but he didn't. Four years later, Sara Snow appeared in Fire & Blood (2018).

And much later, GRRM had a second opportunity to erase Sara Snow from the books with the publication of The Rise of the Dragon (2022), that is basically an art-book of Fire & Blood, the text of which has been boiled down to make room for over 180 new illustrations.

One of those brand new illustrations is one of two dragon eggs that Vermax supposedly left deep beneath Winterfell . . . .

The dragon's eggs could be an allegory of a real baby of Jace and Sara as the fulfilment of the Pact of Ice and Fire. It also has allusions to the tale of Bael the Bard and the Rose of Winterfell, that also alludes to Rhaegar and Lyanna, and consequently to Jon Snow.

So, GRRM had TWO opportunities to erase Sara Snow from the books, but he didn't.

#anon asks#grrm#the world of ice and fire#fire and blood#the rise of the dragon#sara snow#they can cut it from the show tho#but the show canon is not book canon#we will see!

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

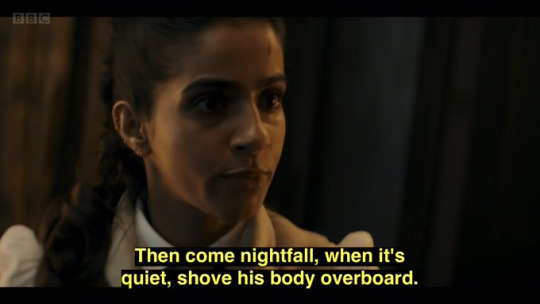

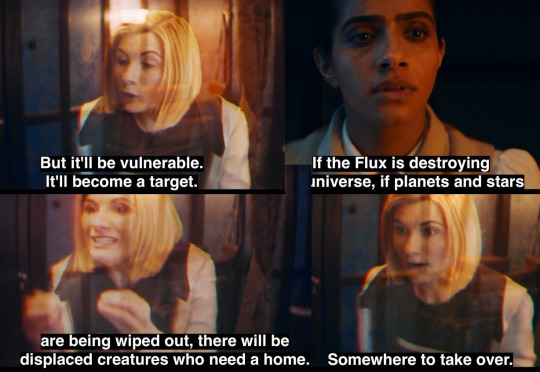

Thirteen Era Rewatch: Survivors of the Flux

I'm re-watching Thirteen's era in lead up to the Centenary and since this is likely going to be my last full re-watch for a while I thought I'd do a post on each ep where I just go over all the things I love, hate or just have some general thoughts on.

When S13 aired I made a posts similar to this after re-watching each ep before the next one came out. The Survivors of the Flux post can be found HERE.

Idc that the angel thing was over quick and idk why ppl get annoyed about it. They explain they did it to transport her and bc it was fun, that’s a good enough explanation for me. Tbh looking back I think ppl (including me) going on about how she’s gonna escape and if the ep was gonna be Doctor-lite was clown behaviour.

I love seeing how much travelling with the Doctor has changed companions and I also love Dan and Jericho being there to show the difference in a companion who’s been with the Doctor for ages and ppl who’ve only just joined

Low-key I think ppl overreact to this scene. Clearly it’s worded bad bc so many ppl have take it badly but when I first watched it I really didn’t see an issue tbh. Maybe 13 coulda clarified that sure, some creatures will peacefully be looking for a home but a lot of creatures won’t be peaceful and that’s who Yaz should be looking out for. I think the idea that 13 specifically is saying ‘Yeah all refugees are bad’ is insane, bc obviously the Doctor wouldn’t believe that. It’s just a case of the writers not thinking about how they worded something

I love the hologram scene like the idea that 13 probs left that hologram for Yaz in part bc she had info to tell her but also bc she knew how Yaz was last time she was left for a long stretch of time is my fave thing ever

I wonder if Dan and Jericho happened to be done with the body just as Yaz got done watching the hologram or if they stood outside the door waiting for her to be done

Tecteun is such a bitch and I hate her but also she’s so great and her and 13 have a 10/10 vibe, they’re so interesting to watch. I know a lot of their part in this ep is literally just them talking but I like it a lot

The ood looks kinda weird like it’s not slimy enough and it’s eyes feel to cartoony

The way 13 reacts here fucks me up idek

Like mother like daughter I guess..

Lol at Jericho getting a beard out of nowhere

Also lol at how Yaz and Jericho swap waistcoats midway through the scene? When they first start painting Jericho is in a green waistcoat, Yaz is in a beige one. And then literally the shot after the ss of Yaz in beige is Jericho in beige and then we see Yaz in green

Tecteun having the Doctor’s fob-watch of memories just like, on display is so sinister to me idk

The way Tectuen just dies instantly like that simultaneously makes sense bc like, Swarm and Azure defo would be motivated to just kill her off, but also seeing her just be gone so quickly feels weird. But then also also, part of me doesn’t even feel like she’s THAT important anyways, like obviously who she is is a big deal, but what use is there for her? Other than the fact she set up the Flux and let Swarm out, I couldn’t ever see her becoming like a recurring villain. I wouldn’t want her to become a recurring villain. She might as well just be dead

I don’t know what’s going on with the Grand Master ngl. Like I know he’s infiltrated UNIT or something and has killed a bunch of ppl with his scarf snake and Kate is like I’m onto you bro but idk why he’s doing it or why he needs to be part of the series other than his shit with Vinder in 13.03. Maybe I just wasn’t paying enough attention but idk. After 13.06 I’m literally gonna read his wiki page so I can fully understand the point in him but I still feel like I’m gonna come to the conclusion that he didn’t need to exist

1 note

·

View note

Note

I was thoroughly thrilled with the finale! My thoughts:

Yaz is alive! Dan is alive! But most importantly Yaz is alive and totally fine for now

Jericho is unfortunately not alive, which is sad because I got really attached to him

c a n o n b e d r o o m c o r r i d o r

13 getting split up at the beginning got me in my Valeyard themed clown makeup ngl

That scene! At the end! Sweet catharsis!

Hughughughughug we got a hug boys it happened

Time as a character was really cool and I loved how they were portrayed. 13-as-villian was deliciously sinister.

We were all busy shipping Thasmin and then they turned around and gave us 13 flirting with herself

I liked the resolution with the watch because I thought it would be a hard sell if she got all her memories back but also it would have really sucked for them just to be destroyed

In true Doctor Who fashion, Karvanista ends up with companions of his own after leaving the Doctor

Actually the stuff with him really hit me. It felt awful watching a former companion be so betrayed and hurt and angry with the Doctor. That scene with them both in the cage was reeeeaaalllly good.

Is this the first time 13 has said companion?

I knew we had to have a scene with multiple Doctors at some point but when Alternate 13 walked in I was s h o o k

Also been a while since we had a torture scene in this show

Kate! Kate! Kate! Kate! Kate! Love her, wish we could have had more

Azure talking to 13 was great because it felt like she really didn't see what they were doing as wrong and that was Fascinating. Up until now Swarm was my favorite but she swooped in and stole the spot with that scene.

Can't believe they Monsters Inc.-ed the Grand Serpent at the end

Uh-oh Time foretelling the Doctor's demise, gives me 10 vibes

also, the Master. Pretty obviously coming back right?

Dan has officially decided to travel with them now!

Overall this season has been fantastic! Every episode felt like it was better than the last, which is really hard to do and I'm impressed. It's probably going to be my favorite of 13's run, though I'll have to wait for the excitement to die down to know for sure. It's been a pleasure sharing my thoughts here, I've had a lot of fun. I'm probably going to go on an internet blackout soon to avoid spoilers, so you won't hear from me for a while. But one day, I shall come back. Yes, I shall come back.

YES EVERYONE IS ALIVE and I know Yaz at least makes it all the way to the centenary special!!

I fell in love with Jericho so yeah that scene HURT

canon bedroom corridor canon bedroom corridor canon bedroom corridor. fic writers are quaking (it's me i'm fic writers)

the hug was everything i hoped for and more, and the embodiment of time?? evil jodie?? i combusted

debatably my favorite part of the episode was the "you're cute!" "Thanks, so are you!" and the "I have got such a crush on her" I DIDN'T KNOW HOW MUCH I NEEDED THAT UNTIL IT HAPPENED

and i completely agree on the subject of her memories. I figured she wouldn't get them back for a few reasons but i'm glad they're not just,,, gone and lost again forever.

yeah no the stuff with Karvanista was unexpectedly sad. (hate to admit the howling scene made us all laugh though) and yes I think this has to be the first time she's said companion bc I went all eye emoji when she did

the torture scene did me in let me tell you

KATE. wish she could've had a bit more screen time but it's at least hinted we'll see her one more time before jodie's run is up??

I liked that azure finally got a really good chunk of plot-driving content bc she was just kind of there as a side piece for swarm for most of the series. That whole scene was incredible

monster's inc'ed i loved that

so i thought i was home alone while i was watching the Time scene where she says "your time is coming to an end" and that was the first time they've even begun to set up her regeneration you know?? a few years ago that would've had me crying like a baby but i can't really cry anymore so i just started LAUGHING HYSTERICALLY FOR A FEW MINUTES and i look over and my roommate is standing in my doorway looking at me like i'm crazy

SO EXCITED WE GET MORE DHAWAN!MASTER CONTENT WHILE WE STILL CAN

It struck me as weird giving Dan the official companion invite this late in?? since he's only got three episodes left?? but hey I'm here for it!

I always looked forward to getting your post-episode rambles in my inbox so thank you!! take care and i'll eventually see you around!!

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

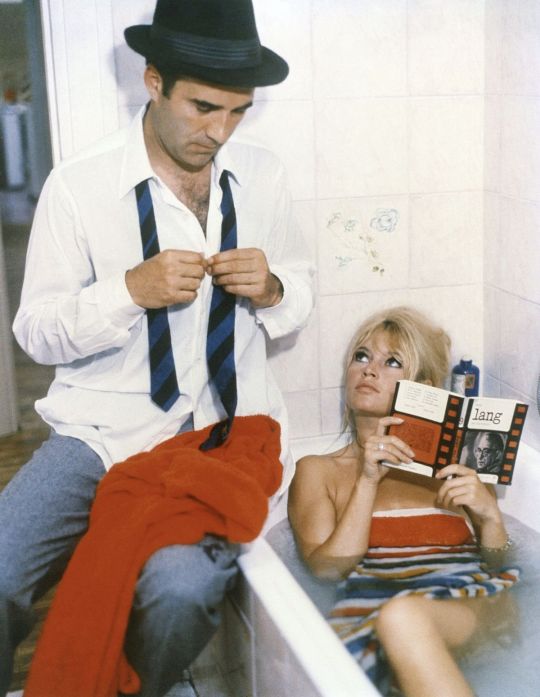

Michel Piccoli obituary

Stalwart of French cinema whose prolific career included films with Luis Buñuel, Jean-Luc Godard and Claude Chabrol

By Ronald Bergan

For more than half a century, there seemed to be one constant in French cinema – the actor Michel Piccoli. With his death at the age of 94 something vital has disappeared from the screen.

Never young looking – he was prematurely bald – Piccoli grew in maturity and power over the years, with directors such as Luis Buñuel, Jean-Luc Godard, Claude Chabrol, Marco Ferreri and Claude Sautet seeking his services more than once. He also worked for directors of the stature of Alfred Hitchcock, Henri-Georges Clouzot, Jacques Rivette, Costa-Gavras and Louis Malle.

Even when he was a big name, Piccoli was never too proud to play small supporting roles or even bit parts if he liked the screenplay. But whatever the size of the role, whether playing a goody or a baddie, Piccoli would bring to the character a gravitas (with a tinge of humour) and an ironic detachment, simultaneously revealing a real, recognisable human being beneath the surface.

Piccoli was born in Paris to a French mother and an Italian father, both of them musicians – his mother was a pianist; his father a violinist. At 19, he made his screen debut in a walk-on part in Sortilèges (1945), directed by Christian-Jaque.

After several roles in the cinema and theatre, he met Buñuel. “I wrote to this famous director asking him to come and see me in a play. Me, an obscure actor! It was the cheek of a young man. He came and we became friends.” Piccoli appeared in six of Buñuel’s films, usually cast as a silky, authoritarian figure.

His first performance for Buñuel was as a weak, compromised priest trekking through the Brazilian jungle in La Mort en Ce Jardin (Death in the Garden/Evil Eden, 1956). In Diary of a Chambermaid (1964), he was the idle and lecherous Monsieur Monteil, sexually obsessed with Jeanne Moreau as the maid Célestine.

Just as louche was his smooth bourgeois gentleman who persuades a respectable doctor’s wife (Catherine Deneuve) to spend her afternoons working in a high-class brothel with kinky clients in Belle de Jour (1967). Piccoli reprised the role charmingly almost 40 years later in Manoel de Oliveira’s Belle Toujours (2006).

He was discreetly charming as the Marquis de Sade in Buñuel’s La Voie Lactée (The Milky Way, 1969), subtly overbearing as the home secretary in The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie (1972) and sinister as a prefect of police in Buñuel’s penultimate film, Le Fantôme de la Liberté (The Phantom of Liberty, 1974).

In the 1950s, apart from his one film with Buñuel and his appearance as María Félix’s jealous lover in Jean Renoir’s French Cancan, Piccoli was cast mainly in run-of-the mill “policiers”. During this period, Piccoli was part of the Saint-Germain-des-Prés set in Paris, which included the writers Boris Vian, Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, and the café singer Juliette Gréco, to whom he was married from 1966 to 1977. He was also an active member of the French Communist party.

The 60s was his most creatively exciting and varied decade. His first leading role (with Serge Reggiani and Jean-Paul Belmondo) was as an unscrupulous gangster in Jean-Pierre Melville’s Le Doulos (The Finger Man, 1962).

This led to one of his best remembered parts, as Brigitte Bardot’s husband in Godard’s Le Mépris (Contempt, 1963), in which he plays a screenwriter, willing to sell his wife to a producer (Jack Palance) in order to get his script filmed by Fritz Lang. In a homage to Dean Martin’s character in Vincente Minnelli’s Some Came Running, Piccoli wears a cowboy hat in the bath.

As memorable as this image was the name of the character he played in Jacques Demy’s Les Demoiselles de Rochefort (The Young Girls of Rochefort, 1967). As Simon Dame, he is continually being greeted as Monsieur Dame (a joke that works only in French), and is rebuffed by Danielle Darrieux, who cannot bear the thought of being called Madame Dame.

It was in 1968 that Piccoli met Ferreri, who starred him in Dillinger È Morto (Dillinger Is Dead), a bleak study of alienation, in which a man’s life is laid bare. Piccoli is brilliant as an industrial designer who, while spending an evening at home, making himself a meal, watching TV and seducing the maid, decides to kill his wife and go to Tahiti.

It was the first of seven films the actor made for the Italian-born director, the most infamous being La Grande Bouffe (Blow Out, 1973), an excessive film about excess, where Piccoli as a TV personality, along with a pilot, a judge and a chef, all bored with life, literally eat themselves to death.

Piccoli’s few roles in English language films were less than challenging: they included his secret agent in Hitchcock’s Topaz (1969) and the suave card dealer in Malle’s Atlantic City (1981).

He was much happier in France, where his talents were not only respected but revered. His several films for Sautet showed him as a complex and flawed hero, starting with Les Choses de la Vie (The Things of Life, 1970), in which he played a man who, although having an affair, finds himself still attached to his estranged wife, his son and friends, and consequently unable to make the absolute commitment his lover requires.

In 1973, Piccoli formed a production company which kicked off with that year’s Themroc, directed by Claude Faraldo, in which he played a factory worker, living in a squalid flat with his mother and sister, pursuing an existence of repetitive routine and urban grind, before he rebels. What made this biting social satire particularly unusual was that language was abandoned completely, with the characters having to communicate in a series of formless noises, something Piccoli does particularly effectively.

Piccoli then returned to his speciality – the urbane bourgeois – in Chabrol’s blackly comic Les Noces Rouges (Blood Wedding, 1973), where he played a mayor’s deputy having an affair with his boss’s wife. In Godard’s Passion (1982), he was a factory owner whose wife is having an affair with a film director.

He gave three of his largest and most impressive performances in his late 60s and 70s. In Malle’s Milou en Mai (Milou in May, 1990), he is the ideal repository of all the director’s sympathies, the upholder of the best of traditional country values, unambitious, unacquisitive and a lover of nature, in contrast to his greedy middle-class family gathered for a funeral.

Rivette’s La Belle Noiseuse (1991) cast him magisterially as a famous artist trying to capture a new nude young model on canvas. In Oliveira’s Je Rentre à la Maison (I’m Going Home, 2001), Piccoli struck a personal and poignant note as an actor trying to deal with old age, and refusing to compromise his principles.

He shone in what amounted to almost a cameo as the courtly but bumbling elderly relative of the Duchess of Langeais (Jeanne Balibar) in Rivette’s Ne Touchez Pas la Hache (Don’t Touch the Axe, 2007), a version of Balzac’s novel on erotic obsession.

For the English language The Dust of Time (2008), Theo Angelopoulos’s last film, Piccoli joined such stalwarts of European art cinema as Bruno Ganz and Irène Jacob in a love triangle that covers the latter part of the 20th century. Despite some of the stilted dialogue, Piccoli bares the soul of a character whose sufferings include his internment and escape from a gulag.

He dominated every moment as a reserved and modest cardinal who panics when elected pontiff in Nanni Moretti’s semi-satire Habemus Papam (We Have a Pope, 2011). The first close-ups of him, when he realises he has been appointed the new pope, suggest, with subtle expressions, emotions ranging from surprise, humility, ambivalence, excitement and then horror.

In Vous N’avez Encore Rien Vu (You Ain’t Seen Nothin’ Yet, 2012), Alain Resnais’ intriguing, self-reflective examination of actors and acting, film and theatre, Piccoli, playing himself, is the doyen in a cast of leading French actors of the day.

He directed the features Alors Voilà (1997) and La Plage Noire (The Black Beach, 2001), the former winning the Critics’ prize at Venice, to add to the many prizes he had won as an actor. It was appropriate that when Agnès Varda filmed One Hundred and One Nights for the centenary of the cinema in 1995, she cast Piccoli as Monsieur Cinema.

He was married three times. His first two marriages, to Eléonore Hirt and to Gréco, ended in divorce. He is survived by his third wife, the screenwriter Ludivine Clerc, whom he married in 1978, and by his daughter, Anne-Cordélia, from his first marriage.

• Michel Piccoli, actor, born 27 December 1925; died 12 May 2020

© 2020 Guardian News

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at http://justforbooks.tumblr.com

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

An Epidemic Every 100 Years:

Plague of 1720, Cholera of 1820,

Spanish Flu of 1920, Coronavirus of 2020

– Is it Just a Coincidence?

There is a theory that every 100 years a pandemic erupts on the planet. It might be a coincidence, but the chronological accuracy is troubling.

In 1720 there was a plague, in 1820 – cholera, and in 1920 – Spanish flu…

Many researchers say that the current coronavirus epidemic resembles the events of previous centuries.

The logical question arises: what if these pandemics were artificially staged by some sinister force? Maybe a secret organization?

1720:

In 1720, there was the last large-scale bubonic plague pandemic, also called the great plague of Marseille. The catastrophic plague led to the death of 100,000 people. It is assumed that the bacteria are spread by flies infected with this bacteria.

1820:

The first cholera epidemic occurred on the centenary of the 1720 pandemic. It has affected Asian countries – the Philippines, Indonesia, and Thailand. Interestingly, about 100,000 people were killed in this epidemic. The pandemic is said to have started with people who drank water from lakes contaminated with this bacteria.

1920:

The Spanish flu appeared 100 years ago, at a time when people were battling the H1N1 flu virus, which had undergone a genetic mutation, which made it much more dangerous than the normal virus. This virus infected 500 million people and killed more than 100 million people in the world, this pandemic was the deadliest in history.

2020:

It seems like history repeats itself every 100 years, is it just a coincidence?

Today, China faces a major pandemic and has spread to South Korea, Iran, Italy, and other countries. More than 77,000 have been infected, over 2,000 have died. But every day the situation gets worse.

The worst part is that air travel and modern technology are accelerating the spread of the virus worldwide. And how it will end, only God knows …

— The Real Healthy Thing

0 notes

Link

In reality, very few Russians are sinister mobsters who poison their foes with polonium or dangle them from skyscraper balconies. But western TV and cinema are very different from reality. In the 21st century, their on-screen representations rarely break out of that sinisterly psychotic stereotype. When are TV Russians going to be the good guys? Never is the Guide’s guess. There’s too much popular cultural investment in depicting them as evil mobsters, as the implacably butch Other to relatively mimsy westerners.

In the centenary year of the Russian revolution, the west is still bewitched by this threat – specifically the mob, which seems bent on exporting its criminal values over here. And the fact that Russia is currently led by an ex-KGB demagogue who burnishes his masculinity issues by hunting half-naked and, according to the news media, may or may not have had a role in hacking the US presidential election, doesn’t help either.

Arguably, Russians are the go-to stereotypes in popular culture right now because, in western nightmares, that stock character resonates with the image we have from the news of President Putin as an implacable hoodlum bent on subverting democratic values.

These kind of thoughts are preying on the minds of the makers of looming BBC drama series McMafia, starring James Norton, which is based on Misha Glenny’s book of the same name. In it, screenwriter Hossein Amini, along with writer-director James Watkins, has focused on a Russian criminal family whose new head is played by Norton.

Amini claims that what he has written avoids the otherwise ubiquitous Russian stereotypes. “The cliche is that they’re a bunch of goons in sharp suits,” Amini says. “What’s often missing from that is that they’re incredibly rich culturally; this is the land of Chekhov and Dostoevsky.”

And yet, as the Guide chats to Amini and Norton during a break in filming, the star of the show can’t quite resist telling me a story about how scary and tough Russians are. Recently, Norton underwent training in the Russian martial art of Systema for his new role. His trainer, David, explained the difference between English and Russian temperaments. Norton impersonates the Systema expert in his best sinister accent: “In England when you see fear you run. In Russia we see fear we shake him by the fucking hand.” Norton giggles amiably. But the point of the story is that even real-life Russians, sometimes, get a kick out of playing up to the hard-man image.

We’re enjoying the spring sunshine on the lawns of Munden House near Watford, which serves as a Russian mobster’s mansion for the eight-part drama series. Norton stars as Alex Godman, a young Russian-born British hedge-fund trader who’s sucked into the corrupting vortex of his family’s crime business. “It’s about someone who finds the Russian bear underneath the bowler hat,” explains James Watkins. What the director means is that beneath the genial suavity of British civilisation is the scary Russian psychopath, who’ll separate you from your windpipe if you look at him wrongly.

You’ll find Russian bears everywhere on TV and movies these days – and not just under the bowler hat. Many shows now seem to have a tough Russkie with mob connections, ideally played by a non-Russian actor, to up the narrative ante. In Orange Is the New Black, for instance, Galina “Red” Reznikov, played by Iowa-born Kate Mulgrew, rules her corner of Litchfield Penitentiary with an iron fist akin to Putin’s helmsmanship of the Kremlin. Plus, Mulgrew brings to the role the same gravitas she gave her character Kathryn Janeway in Star Trek: Voyager.

How did Red (named after her distinctively coloured hair) come to be in the slammer? She punched the wife of the local Russian mob boss in the chest, rupturing the latter’s breast implant. As a result, Red and her husband Dmitri were obliged to pay the repair costs through tasks including storing five corpses of mob victims in their freezer – corpses that led to Red’s conviction for murder. Moral? Punching mob boss’s wives in their breast implants is never a good idea.

What’s also striking is how well this stereotype plays with viewers and critics, at least non-Russian ones. When the mob comes to town to get vengeance in the recent fourth season of Ray Donovan, for instance, one critic wrote: “I love this show’s cold war-esque portrayal of Russian culture/mobsters. They’re all criminal drug addicts!” Liev Schreiber’s eponymous La-La Land enforcer is badass, but not as badass as what one US critic was pleased to call “Dmitri and his entourage of evil”. Having duffed up Ray’s Israeli muscle Avi and taken him hostage, Dmitri (New Yorker Raymond J Barry) phones Ray to demand the return of his relative. Or, as he puts it, terrifyingly: “Mr Donovan, bring me my niece or I kill your Jew.”

And that’s the problem: 21st-century Russians rarely break out of the psychotic stereotype on western TV or cinema. Even in Arrow, the adaptation of the DC comic about billionaire playboy Oliver Queen who is also a secret hooded vigilante, we learn that our hero’s backstory includes post-shipwreck years as a captain of the Russian mob. That’s why our hero can speak the language and why, in a flashback in season five, we see Queen go toe-to-toe with Dolph Lundgren’s Russian government strongman Konstantin Kovar, who resembles Putin with bigger pecs. Lundgren, significantly, has made a successful career from playing Russian hardmen. In 1985, at the height of the Reagan-era cold war, he played Soviet boxer Ivan Drago in Rocky IV, whom patriotic American Sylvester Stallone (in stars and stripes boxing shorts) was obliged to take down in a symbolic bout prefiguring by four years the fall of the Soviet Union. Then, Dolph was the symbolic patsy losing the old cold war for the Russians; in Arrow, more than three decades later, he’s the symbolic patsy losing the new one for them.

Dolph Lundgren, by the way, is not Russian, but Swedish.

Will McMafia buck or conform to the stereotypes? On the lawn of Munden House, James Norton tells the Guide that he hopes his performance will remind us that Russians are different to what is considered the norm on cinema and TV. He says that one reason he wanted to play Alex, the Anglo-Russian who’s both revolted and seduced by his family’s criminal past, was that he is so conflicted. While Alex is proud of his Russian roots (“He has a Dostoevsky book at his bedside and he goes to Systema classes a couple of times a week”) he also agonises over what being Russian means. Will Norton manage to bring such complexities to life, bucking the trend of stereotyping them as thugs? “I hope for Russians’ sakes it counters those cliches. There’s so much negative propaganda about Russia at the moment that we digest. Some of it’s true and some of it is certainly not.”

McMafia will air next year on BBC1

29 notes

·

View notes

Link

Six years ago, the Chinese president Xi Jinping made a state visit to Britain. It was an important moment for both nations — the launch of a new “Golden Era”— designed to show that any differences caused by David Cameron’s meeting with the Dalai Lamai in 2012 were forgotten. Behind the scenes, however, it was preceded by months of difficult negotiations as Downing Street tried to meet Beijing’s conflicting demands for a schedule that showed their President to be an ordinary man of the people, while also according him with the respect that befits the leader of a nation better than any other on earth.

Finally, when they unfurled the flags for Xi’s three-day trip, there was lunch for the Red Emperor with the Queen, a glitzy state banquet, two nights at Buckingham Palace and an address to Parliament. But there were also pictures of the President standing aboard a London bus, enjoying fish and chips over a pint with Dave and hanging out with football stars in Manchester — all designed to reinforce the narrative of an ordinary bloke who happened to be ruling one-sixth of the world’s population.

“He has a confident and bullish exterior — he sees himself very much as the big leader,” wrote Cameron in his biography. “But behind the scenes I found him reflective and thoughtful.” Yet there seems surprisingly little wider interest in this enigmatic character who changed the course of China and now seeks to reshape the world.

That state visit came at a time of greater optimism, when many people beyond the Tory leadership fell for the delusion that China might be nominally a Communist country but, propelled by capitalism and consumerism, was sliding inexorably down a path towards greater freedom. How different the world looks today — and not just due to the devastating pandemic that mysteriously emerged from the heart of China, made all the worse by the state cover-up.

MORE FROM THIS AUTHOR

The WHO's Covid shame

BY IAN BIRRELL

Indeed, there is a growing consensus that this is a country intent on pushing its dictatorial creed in a tussle for global supremacy against Western liberal democracy. It is a nation which has inflicted genocide on Muslim minorities, throttled freedom in Hong Kong, threatened Taiwan, sabre-rattled on borders in the Himalayas, developed a sinister surveillance society and even infiltrated our universities to scoop up their latest research.

All of which makes the lack of curiosity surrounding the most powerful Chinese leader since Mao Zedong seem rather strange. As Jeffrey Wasserstrom, a professor of Chinese history, recently asked: “Why are there no biographies of Xi Jinping?”. Their absence is all the more striking when you consider that China’s ruler is not simply far more important than the likes of Russian President Vladimir Putin, who has spawned a small library of books; he is also a fascinating figure with a compelling life story.

Lurking behind that calm facade lies a childhood tale that helps cast some light on Xi’s controlling policies and his aggressive nationalism. Bear in mind that it is Xi who turned his nation back towards harsh totalitarianism, ordered his acolytes to ratchet up repression in Xinjiang and broke any pretence of keeping to the handover deal with Britain to protect Hong Kong’s freedoms. He has ditched term limits to retain power, crushed party foes, stifled domestic dissent and enshrined his name in the party constitution, elevating his position and ideology to the status of Chairman Mao. It is hard to disagree with the view of former Australian prime minister Kevin Rudd that he is “the most formidable politician of our age”.

It does not take a psychologist to see that the seeds of his ruthless desire for order, his rigid toughness and perhaps even his political pragmatism may have been sown during his turbulent background, even if it is hard to disentangle the myths from the man. Like any smart modern politician, Xi knows the power of public relations and has worked hard over the decades to create an image that dovetails with both his personal and national desires. Hence those “man of the people” pictures over a pint down The Plough with Cameron.

SUGGESTED READING

How China bought Britain's universities

BY MARK EDMONDS

Like his British host, Xi had an elite upbringing that involved attendance at one of his nation’s finest schools — although in his case, this led only to trouble and tragedy during the chaos of the Cultural Revolution. Xi, born in 1953, is the son of Xi Zhongxun, a Communist revolutionary hero who was close to Mao and became a vice premier. Although China was riddled with poverty, this prominent family lived in a compound for party chiefs with their own cooks, nannies and drivers. One official biography claims that his parents sought to ensure their children were not spoilt, so he wore clothes handed down from his siblings — including floral shoes from his sisters that were dyed black. His father, meanwhile, was so strict that friends said his treatment of his son bordered on inhuman, and Xi also attended the “CCP aristocracy school” in Beijing infamous for military-style discipline. Any hint of softness, said one classmate, was seen as weakness.

Disaster struck when he was nine. His father fell out with Mao amid party in-fighting, so was sent to work in a factory in central China and his family lost its prized home —although his mother Qi Xin retained her party job in Beijing. Worse came in the 1966 Cultural Revolution, with its brutal purging of senior officials as enemies of the state. His father was beaten, paraded on a truck through jeering crowds and jailed. The family home was ransacked by militants, his mother forced into hard labour on a farm. Xi, a bookish boy, was made to denounce his father and bullied by teachers as the child of a “black gang”, the term for disgraced officials. His older sister eventually killed herself after being “persecuted to death”.

The following year Xi’s school was shut down and turned into an exhibition to showcase the pampered privileges of the reactionary elite. At the age of 14, he was caught by a gang of revolutionary Red Guards, who threatened to execute him before making him read quotations from Mao. Another time, he fled from a meeting attacked by students armed with clubs, who caught and badly beat one of his friends. “I always had a stubborn streak and wouldn’t put up with being bullied,” he claimed later. “I riled the radicals and they blamed me for everything that went wrong.”

There can be little doubt that Xi suffered as the son of a prominent man who was purged repeatedly for remaining loyal to his lifetime cause of communism. Xi himself only evaded jail after Mao, seeking to regain control of spiralling chaos, ordered 30 million young city dwellers into the countryside for “re-education” by peasants. Analysts speculate this difficult period in his teenage years led to Xi’s ability to hide his feelings beneath an impassive surface, along with the development of his fervent desire for stability. “This generation had everything taken from them so they have the survival instinct,” said Kerry Brown, professor of China Studies at King’s College, London. “They had to deny who they were. It becomes all about control with no room for ego.”

SUGGESTED READING

China's plan for medical domination

BY STEVE BOGGAN

Xi has since made much of the seven long years he spent as a “son of yellow earth”, living from the age of 15 in a cave dwelling in a remote, impoverished village in Shaanxi region. “I felt lonely at first,” he admitted in his autobiography. He found it a shock to eat rough peasant food, sleep on flea-ridden blankets and perform hard rural labour. Dozens of others sent to this region died from disease or the tough conditions. Instead Xi developed extraordinary self-discipline: “The knife is sharpened on a stone, people are strengthened in adversity,” he said later.

His loathing of chaos was fuelled later by the collapse of the other major twentieth-century Communist empire. “Why did the Soviet Union disintegrate?” he once asked. “In the end nobody was a real man, nobody came out to resist.”

Yet during those formative years he also saw the danger of extremism, when children had free reign to kill and torture in the name of delivering utopia. Did this all leave him with the pragmatism needed to achieve his goals? A leaked US diplomatic cable, based on information from a friend, reported that Xi focused from an early age on reaching the top as an “exceptionally ambitious” character. Unlike many youths who “made up for lost time by having fun” after the Cultural Revolution, Xi “chose to survive by becoming redder than the red”, reading Karl Marx and laying foundations for a political career. He was seen as “cold and calculating”, deemed “boring” by women.

Now he wants to impose his will on the world, having navigated a path through the choppy waters of the Chinese Communist Party. Today, our challenge is not China, that huge land of epic history and extraordinary culture; it is President Xi and his vision of total control. His goal is clear: to make his country great again while usurping the global leadership of the United States — and he does not hide his aims.

In a speech to his party’s 2017 National Congress, Xi laid out “the Chinese dream of national rejuvenation”: to finish building a prosperous society by this year, centenary of the party’s birth; to assume global economic and military leadership by 2035; then to “resolve” the Taiwan issue by 2049, centenary of the People’s Republic, to conclude their rebirth as a “strong country”.

At the centre of his vision lies the Communist Party, firmly in control of everything in China, aided by skilled propaganda and use of technology to control his people in Orwellian style as they walk, talk, shop and work. Such is Xi’s sway that a smartphone app was developed which allowed users to compete over who could virtually applaud that party congress speech with the most enthusiasm — more than one billion claps were recorded in 24 hours. Two years later, the most downloaded app in the country was “Study the Great Nation”, which combined chat and games with quizzes about Xi’s ideology — a digital update on Mao’s Little Red Book designed to ensure compliance and diligence from citizens.

When Xi first met Putin in 2013, he told the Russian president: “We are similar in character.” There is truth in this statement, yet the Chinese leader is far more subtle and ambitious. Xi Jinping sees himself as a saviour of his creed and a man of destiny for his country, a ruthless character driven by fierce resolve inflamed by that suffering of his youth. He is the very embodiment of that Confucian saying: “To be wronged is nothing unless you continue to remember it.”

0 notes

Link

Artist: Christina Ramberg

Including Works By: Alexandra Bircken, Rachal Bradley, Sara Deraedt, Gaylen Gerber, Frieda Toranzo Jaeger, Konrad Klapheck, Ghislaine Leung, Hans Christian Lotz, Senga Nengudi, Ana Pellicer, Richard Rezac, Diane Simpson, Terre Thaemlitz, Kathleen White

Venue: KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin

Exhibition Title: The Making of Husbands: Christina Ramberg in Dialogue

Date: September 14, 2019 – January 5, 2020

Curated By: Anna Gritz

Click here to view slideshow

Full gallery of images, press release and link available after the jump.

Images:

Images courtesy of the artists, the Estate of Christina Ramberg and KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin

Press Release:

“Containing, restraining, reforming, hurting, compressing, binding, transforming a lumpy shape into a clean smooth line,” is how American artist Christina Ramberg (1946–1995, US) once described the drawings of corsets in her sketchbooks. Ramberg was one of the most intriguing painters to emerge within a generation of Chicago Imagists. She left behind a significant body of comic, formally elegant, erotically sinister paintings. Her cropped torsos, sharply delineated and bound in bizarre variations, explore the body in traction with its environment, shaped by corsets and hairstyles, as well as behavioral conventions. A selection of paintings and drawings by Ramberg form the core of the exhibition at KW Institute for Contemporary Art. Shown alongside are works by further artists in order to expand the understanding of the type of framing devices that construct identity— physically, psychologically, and metaphorically.

The exhibition title The Making of Husbands stems from a BBC documentary that traced the making of John Cassavetes’ 1970 film Husbands, picking up on Cassavetes’ interest in the construction of semi improvised behavioral and gender performances and complicating these through the meta-level of the documentary, which attempts to record the supposed “natural” behavior behind the scenes on set. By doing so, however, it reveals the artificiality of stereotypical roles such as “the husband,” the complexities of “acting natural,” and the constructed nature of gender itself.

Artist and educator Christina Ramberg was a dynamic presence in the Chicago creative community from the 1960s up until her death in 1995. Through a plethora of small obsessive drawings, studies in sketchbooks, and a number of highly finished paintings in acrylic on Masonite, Ramberg observed the human body in various forms of modulation and metamorphosis. For her, this pictorial investigation doubled as an inquiry into larger questions concerning power dynamics, hierarchies, gender construction, desire, fetishism, and the increasing standardization thereof. From the early small-scale depictions of women in a state of undress

to the later torso paintings, Ramberg’s surfaces and structural devices gradually merge with the body and become an androgynous prosthetic, a cyborg half-being.

Ramberg’s extraordinarily rich and eccentric personal reference collection of 35 mm photographic research slides (parts of which are reproduced in the exhibition catalogue) reveals a wide range of visual influences on her painting including printed advertisements, fashion layouts, medical illustrations, S/M bondage, hosiery, comic books, folklore and self-taught art, costume history, and quilting. The slides delineate a specific way of looking at the world, at the then contemporary everyday and at canonized visual culture alike. Equally, her collection of collages made from comic books expresses an interest in social conventions and how they are preprogrammed and perpetually re-inscribed through everyday visuals.

Ramberg’s investigation of the body as a kinetic site in reciprocity with its environment is further explored in the accompanying group exhibition. The artistic positions articulate a relation of interdependence between the body and everyday objects, built constructions and infrastructure. They expand our understanding of how governing principles are at work and how they leave imprints on personal expression and social interaction.

Marking the thresholds of the exhibition, Ghislaine Leung’s (born 1980, SE) new commission GATES makes spatial circulation and questions of accessibility apparent and relatable, while her work SHROOMS highlights what is often overlooked or deemed neutral within an institutional body. Similarly accentuating KW’s infrastructure, Gaylen Gerber’s (born 1955, US) Backdrop, fabricated from gray commercial photographic background paper and fitted to cover the gallery walls, draws attention to what is presented and how it is presented, both physically in the space and metaphorically by the institution. In close proximity Sara Deraedt’s (born 1984, BE) photographs span a covert dynamic between desire, household objects and bodies.

Kathleen White’s (1960–2014, US) video documentation of her performance The Spark Between L and D alludes to the complex position of women within the narrative of the AIDS crisis and its biased commemoration. The body as a site that is overly programmed through historical, social, and technological mechanisms is further articulated in the multi-media-based practice of Terre Thaemlitz (born 1968, US). Thaemlitz brings to the fore how the existence of humankind at all times has been grounded by all defining organizational structures.

The sexualized gaze of Konrad Klapheck (born 1935, DE) onto the objects that we produce, such as technical equipment, machines, and everyday tools epitomizes Ramberg’s call for a reassessment of our built environment and its effect on the body. Similarly interested in a surrealistic, excessive take on everyday objects surrounding us, between 1978 and 1986 Ana Pellicer (born 1946, MX) created a series of oversized copper jewelry pieces to fit the Statue of Liberty in New York City for its centenary.

A contemporary of Ramberg, Diane Simpson’s (born 1935, US) sculptures are abstractions of salient gendered garments that make the regulations and liberties that fashion and clothing leave to the body ever more apparent. Associated with a subsequent generation of Chicago artists, Richard Rezac’s (born 1952, US) objects are masterfully balanced structures of contrasting forms, substances, and functions that raise questions about structural and aesthetical integrity. Their inversion of an object’s qualities is akin to Ramberg’s formal transpositions.

Alexandra Bircken (born 1967, DE) explores in her sculptures the boundaries between inside and outside, fragility and protection, visibility and concealment. Bircken’s mechanical and industrial-looking shells become an interface where the body and the world come together, coalesce, and clash. In a similar negotiation between an inner and outer sphere, the painterly installation by Frieda Toranzo Jaeger (born 1988, MX) reconsiders the gendering of the car as an archetypically masculine machine. She repositions the interiors of contemporary, soundless, electric vehicles made by imperialistic manufacturers as intimate, female spaces, in order to question the autonomy of the individual body within a world increasingly characterized by automated control. Embodying this notion of automatization against the autonomy of the artwork, Hans-Christian Lotz’s (born 1980, DE) electric readymade sliding door suggests on the other hand a reading of aesthetic space as something intrinsically transmitted and mediated—it traces the viewer’s movement as they step in and out of its realm of attention.

While articulating yet another structural tension—that of technical devices taken apart, as well as nylon tights reminiscent of skin—A.C.Q. I by Senga Nengudi (born 1943, US) outlines the brinks of a potentially performative space, referring to Nengudi’s ongoing involvement with acts of embodiment and ritualistic environments as sites for political negotiation.

The exhibition is accompanied by a substantial publication that brings together newly commissioned writing on Ramberg by art historians and theorists including Anna Gritz, Larne Abse Gogarty, and Judith Russi Kirshner, alongside experimental fiction texts by Jen George and Dodie Bellamy.

Link: Christina Ramberg at KW Institute for Contemporary Art

Contemporary Art Daily is produced by Contemporary Art Group, a not-for-profit organization. We rely on our audience to help fund the publication of exhibitions that show up in this RSS feed. Please consider supporting us by making a donation today.

from Contemporary Art Daily http://bit.ly/35jCGmG

1 note

·

View note

Text

Starfire Volume 2 No. 3

https://liber-al.com/?p=11430&wpwautoposter=1560874970

Starfire Publishing Ltd, London, 2009. Paperback, full colour cover, sewn binding, large format, 192 pages. Brand New/Fine. The first issue of Starfire appeared in 1986, and it has been an occasional Journal of the New Aeon ever since. Dedicated to Thelema, it brims over with articles and artwork of relevance to the Thelemic current. All previous issues are now out of print and difficult to obtain. This issue was when published the first new issue of Starfire for many years, and as ever is a scintillating collection of articles, short stories and artwork that is sure to delight and inform. Contents include: – The Magic of Folly by Richard Ward – some considerations of ‘The Fool’ card in the Tarot; – Sinister Shades in Yellow by Alistair Coombs – an essay on the work of novelist Sax Rohmer; – The Stone of Stars by Oliver St. John – a fascinating short story woven around a talismanic stone and the forces it calls down; – Tzaddi is not the Star by Caradoc Elmet – some considerations on the Tarot. – The Aphotic Oracle by Daniel Lett – Nightmare Sorcery by Richard Gavin – Maranatha: a Blessing or a Curse by Stephen Dziklewicz – The Altar by Peter Smith – again, a fascinating short story, this time focusing on the history of a lost grimoire. – A Very Personal Tantrum by Joe Claxton – an account of consequences from some specific ritual work – The issue also includes a supplement collecting several presentations from the April 2004 Thelema -Beyond Crowley Conference held in London to mark the Centenary of the transmission of The Book of the Law, including the following: – Looking Forward! by Kenneth Grant – The Letter Killeth by Michael Staley – A Hundred Years Hence by Martin Starr – Calling Mr. Crowley by Andrew Collins – The Evolution of Maat Magick by Margaret Ingalls

0 notes

Text

Christopher Lee: A Sinister Centenary - Number 2

Welcome to Christopher Lee: A Sinister Centenary! Over the course of May, I have been counting down My Top 31 Favorite Performances by my favorite actor, the late, great Sir Christopher Lee, in honor of his 100th Birthday. Although this fine actor left us a few years ago, his legacy endures, and this countdown is a tribute to said legacy!

It's time for the penultimate entry of this special countdown. Today’s Subject, My 2nd Favorite Christopher Lee Performance: Lord Summerisle, from The Wicker Man.

SCREW THE NICOLAS CAGE REMAKE!!! Ahem…sorry, I…seem to be programmed to say that anytime I mention The Wicker Man-SCREW THE NICOLAS CAGE REMAKE!!! Ahem-hem…sorry again. From this point on, I’ll just call “Wicker Man” for safety’s sake.

It helps if I don’t say “the.” :P

ANYWAY…alongside “Jinnah,” Lee considered “Wicker Man” to be his single favorite and best film, and it’s hard to disagree there. This very strange, surreal, and EXTREMELY dark picture is a genre-blending, one-of-a-kind thriller. It’s part horror film, part twist-turning murder mystery, part musical…and all around HIGHLY disturbing, even nowadays. The story follows a police officer, Neil Howie, who attempts to solve the mystery of a small girl’s strange disappearance on the island colony of Summerisle. A faithful Christian, Howie is appalled to discover the island’s residents practice rituals resembling a form of Celtic Paganism. As the story goes on, he discovers a massive conspiracy…a conspiracy that ends in his EXTREMELY horrifying downfall.

A central figure in the unfolding madness is Christopher Lee as the leader of the colony, and a descendant of the island’s founders, Lord Summerisle. Summerisle is a mysterious, strange figure, one who – even all the way up to the end – we’re never able to fully unravel. He is a walking enigma; in some ways a civilized gentleman, reasonable and rational, and really quite friendly. But the fervor with which he commits his crimes and practices the dark rituals of the story creates an air of deep unease. It’s also not entirely clear how truthfully Summerisle BELIEVES in the pagan trials, or even how true they are to any kind of spiritual following: is he a mad cultist, a charlatan leading a band of disillusioned followers, or something else entirely? Perhaps the most disturbing question is if Summerisle is actually RIGHT in what he does, since it's left unclear if all his wicked workings even have the desired effect in the end or not. Only the audience can truly decide for themselves what is true and what is false.

This role, in essence, gives one EVERYTHING they could want out of a great Christopher Lee performance, giving the actor a chance to show nearly the full breadth of his range as a performer all in one shot: he gets to sing, and he gets to dance. He has scenes of manic, wild power, and scenes of subtlety and softness. He has scenes where he is terrifying and intimidating, and scenes where you almost forget to be scared at all. The ambiguities of the character only help to add to the power of the part. It’s easy to see why this was one of Lee’s personal favorite roles, and I actually very, VERY nearly gave Lord Summerisle the number one slot…but the more I thought about it and inspected the situation, the more I felt that wasn’t quite right. Lord Summerisle is phenomenal, but there’s one Lee performance I like more…but I mustn’t say more, or I shall spoil what’s coming next.

On that note…tomorrow, we reach the end of the countdown. Who will be my number one favorite? You’ll have to stick around to find out! ;)

#christopher lee#sinister centenary#happy birthday christopher lee#top 31 christopher lee performances#may special#number 2#best#favorites#list#countdown#the wicker man#lord summerisle

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

undefined

youtube

Witty Angels and the humour of religion

Kevin Smith

Dogma 1999

Beginning with a warning about the contents of the film in the hopes of not offending anyone didn’t work out too well.

Kevin Smith’s Dogma is extremely difficult to buy at least for any reputable retailer; and not available at all in an online digital copy.

In a general sense Kevin Smith’s films are very different to most you will ever see. They have realistic characters, in a manner of speaking, with large vocabularies and witty comments. His films are told through jokes, sarcasm and other forms of sometimes crude humour.

Although still with the usual drugs and sexual references of his films, Dogma changes the focus to religion.

The Characters in Dogma are realistic in the flawed kind of way, but they also include fallen angels, demons, the last scions, an apostle, prophets (also drug dealers), a muse, and the voice of god all being thrown into a holy crusade.

So not as realistic as other Kevin Smith films.

Dogma is not just a reflection on Catholicism but also of religion in pop culture, and as most films tackling these huge topics, there is much to talk about.

Hence, just the introduction up to the title will be looked at.

The opening sequence is spread over three scenes, only one is specifically distinct, the other two are woven together to set up the events of the film.

Opening with the beach and the soon to become John Doe doesn’t make much sense during the first viewing but does foreshadow the film, because of this it becomes essential.

This first opening scene also sets up the themes around the ‘evil’ characters, the ominous music and the sound of flies buzzing. The violence and grimace displayed by the three demon kids as they beat John Doe senseless provides the base line of violence to be portrayed through the film. Not bloody, but violence nonetheless.

The final camera angle from this scene is used to transition to the next.

A low angle shot, John Doe looking up at the three demon kids fades to a low angle shot of a church, thus bringing the next scene in.

A press conference, meaning characters within the film can introduce each other, themes and other aspects to the story without appearing odd.

The introduction of the Cardinal and his campaign Catholicism Wow begins to bring the layers of story into the film and also the almost insanity that is Dogma.

Catholicism Wow in a campaign to make religion relevant to a younger generation and a wider audience. Part if this is Buddy Christ, an animated looking statue of Jesus Christ, pointing with one had, thumbs up with the other and winking.

The transition between scenes from here gets a little less cut and dry, the intertwining of two seperate places, characters and other story elements into a cohesive semi-liner film.

Through the magic of TV we the audience go from a ‘live’ press conference to a TV in an airport in a completely different city.

Pan out and slightly down, now we have Loki (former angel of death) trying to convince a Nun that God isn’t real using Through the Looking Glass to make his point, one of the many pop culture references. Once that is taken care of, Bartleby (another fallen angel) is introduced.

In a matter of a minute the personalities of these two character are displayed, Loki and his cruelty, convincing the Nun that God isn’t real even though he as a former angel knew he was.

Bartleby and his desire to see good in people, sitting in an airport and watching people reuniting and being so happy to see each other.

Moving on, as the dialogue does in a quick manner; a solution to the two fallen angels problem is presented in the form of an article that someone sent to Bartleby.

As Loki begins to read the article out loud, we are suddenly watching the news again; the same reporter finishing the explanation and Loki’s sentence.

The Catholicism Wow campaign givens them a chance to get back into heaven by simply passing through the church archway on the date of it centenary.

This transitions back to Loki and Bartleby traveling through the airport discussing the previously provided information as they go. How church decrees are fallible, but because of dogma what is held true on earth will be held true in heaven.

In the background the Nun that Loki was talking to is getting very, very intoxicated. The background characters and other extras are used in humorous and almost comical ways to cement the main characters within that world. This can be done via interaction of in the case of the Nun reactions from interactions.

Continuing their walk through the airport the topic of mass murder is brought up, to as Loki put it ‘get back on Gods good side’. Bartleby isn’t so sure about this but is reassured by Loki, reminding him that even if God doesn’t like it after that pass through the archway they will have a morally clean slate anyway.

Loki’s desired target Mooby’s is in the background, two guys wearing the Mooby’s shirt, hat, as well as holding a Mooby’s mascots toy. This again is not very subtlety foreshadowing the events of the film.

This trip through the airport concludes at the elevator.

Still chatting between each other, the conversation ‘Last three days on Earth, well we cant get laid so lets do the next best thing’. The answer to this was murder, this caused an extra to spit out her coffee. Loki responded to this by saying ‘Oh, not you’. Once agin the background characters help these two insane characters fit into the world around them.

As the elevator doors close, the screen turns black and the films tittle is displayed.

This opening sequence may not be the entire introduction to the film and it’s main characters, but it does set up the films themes and events as well as humour.

The arrogance of the Cardinal, the events of the past that lead Loki and Bartleby to be stranded on earth. The current goals and personalities of Loki and Bartleby, the sinister foreshadowing of the demon kids, the level of violence, the type of humour and how religion will be viewed through the film. With many a witty comment, paying close attention to the dialogue is imperative.

The density of the film means that it is a great rewatch.

1 note

·

View note

Text

That’s got you wondering hasn’t it? Well … this is nowt to do with me going for a run. I’m not that daft. But I know someone who is. This weekend Mandie took part in the Spitfire 10k at RAF Cosford, which is an annual event designed to raise money for the RAF charity, specifically this year the RAF100 appeal. This is Mandie’s third year of completing the mammoth run around the RAF base so a massive well done to Mandie on completing the course and on getting her winners medal (and lovely associated t-shirt)

My contribution? Well, I went along to support her which was very nice of me as it meant getting up early on a Sunday morning. While she was doing all the running and such like, I went for a bit of a mooch around the museum. Shamefully, as it is no more than 10 miles from my house, I haven’t been here since my Dad was alive and he passed away in 1991 … Still, it was lovely to have a wander about and I will go back again for a proper visit very soon.

Funnily enough I saw a few planes. And some tanks. And missiles. As you do. Well at least you do at an RAF Museum anyway. Managed to pick up a nice ‘tubby pen’ and thermal mug to commemorate the centenary while I perused the shop too. Tidy.

I’m not completely against exercise. On Saturday morning Mandie and I did a nice lap of Attingham Deer Park, a short 3 miles stroll while the weather was nice. Because we made the opening of the park at 0800 we were blessed with seeing squirrels, rabbits, pheasants and lots of the lovely deer who make the park their home. Because I didn’t have my camera ready enough I only have gratuitous deer pics but you can imagine the other animals scampering about …

Because I haven’t quite lost the wanderlust (and because Mandie wants an excuse for time off work) we did another day out, this time to Powis Castle. Again, somewhere I haven’t been in years but it was fab and ended with a quick jaunt to Charlies where I managed to pick up some lovely Flamingo stationery. As you do.

And I managed some reading too. Go me huh? Book wise, I’ve been kind of good. Ish. Four from Netgalley but all for tours so necessity not indulgence. They were The Warning by Kat Croft; Tell Nobody by Patricia Gibney; Hush Hush by Mel Sherratt and one I can’t tell you about just yet, but it looks really good.

#gallery-0-19 { margin: auto; } #gallery-0-19 .gallery-item { float: left; margin-top: 10px; text-align: center; width: 25%; } #gallery-0-19 img { border: 2px solid #cfcfcf; } #gallery-0-19 .gallery-caption { margin-left: 0; } /* see gallery_shortcode() in wp-includes/media.php */

Book book wise I’ve been very good. Only two. First up was the preorder of the second Amy Winter book from Caroline Mitchell (so new it doesn’t have a cover yet), The Secret Child, and I also bought myself a hard back copy of The Way of All Flesh by Ambrose Parry.

Books I have read

The Way of All Flesh – Ambrose Parry

Edinburgh, 1847. City of Medicine, Money, Murder.

In Edinburgh’s Old Town young women are being found dead, all having suffered similarly gruesome ends. Across the city in the New Town, medical student Will Raven is about to start his apprenticeship with the brilliant and renowned Dr Simpson.

Simpson’s patients range from the richest to the poorest of this divided city. His house is like no other, full of visiting luminaries and daring experiments in the new medical frontier of anaesthesia. It is here that Raven meets housemaid Sarah Fisher, who recognises trouble when she sees it and takes an immediate dislike to him. She has all of Raven’s intelligence but none of his privileges, in particular his medical education.

With each having their own motive to look deeper into these deaths, Raven and Sarah find themselves propelled headlong into the darkest shadows of Edinburgh’s underworld, where they will have to overcome their differences if they are to make it out alive.

Oh how I enjoyed this book. In it we meet newly qualified Doctor Will Raven who has somewhat of a questionable past and one which is coming back to haunt him right from the start. Full of mystery, murder and all things medical, and set in 1840’s Edinburgh, I simply flew through the reading of this book, loving the dynamic between Raven and housemaid Sarah, a young woman who was very much ahead of her time. I’ll be reviewing the book this week, but you can buy your own copy here. By the way, if you’d like to see Ambrose Parry in the flesh, aka husband and wife writing team Chris Brookmyre and Dr Marisa Haetzman, they’ll be appearing at Bloody Scotland at the end of the month. You can find all event tickets (if there are any left as it is selling out left, right and centre) here.

…

The Night She Died – Jenny Blackhurst

On her own wedding night, beautiful and complicated Evie White leaps off a cliff to her death.

What drove her to commit this terrible act? It’s left to her best friend and her husband to unravel the sinister mystery.

Following a twisted trail of clues leading to Evie’s darkest secrets, they begin to realize they never knew the real Evie at all…

Ooh what a twisty thriller this is. Telling the story of very new wife Evie, who takes her own life, this story will shock and enthrall readers. Told through the eyes of Evie and her best friend Rebecca there are many secrets to uncover as we try to work out why Evie chose to end her life. The book is released on 6th September and I’m reviewing as part of the tour (I’ll also have an extract) but if you want to buy a copy for yourself you can find it here.

…

The Lion Tamer Who Lost – Louise Beech

Be careful what you wish for…

Long ago, Andrew made a childhood wish, and kept it in a silver box. When it finally comes true, he wishes he hadn’t…

Long ago, Ben made a promise and he had a dream: to travel to Africa to volunteer at a lion reserve. When he finally makes it, it isn’t for the reasons he imagined…

Ben and Andrew keep meeting in unexpected places, and the intense relationship that develops seems to be guided by fate. Or is it?

What if the very thing that draws them together is tainted by past secrets that threaten everything?

A dark, consuming drama that shifts from Zimbabwe to England, and then back into the past, The Lion Tamer Who Lost is also a devastatingly beautiful love story, with a tragic heart…

Gah. This book. Beautifully lyrical, tragically poetic in style and delivery, a story full of love and loss, this moved me to tears. Literally. Just ask my DPD driver who didn’t quite know what to do with himself when I answered the door in a full on red eyed, wet cheeked mess. I’ll be reviewing on the tour, assuming I can find any words, but you can buy a copy of the book here.

…

Ed’s Dead – Russel D McLean

Meet Jen. She works in a bookshop and likes the odd glass of Prosecco… oh, and she’s about to be branded The Most Dangerous Woman in Scotland.

Jen Carter is a failed writer with a rubbish boyfriend, Ed. That is, until she accidentally kills him one night. Now that Ed’s dead, she has to decide what to do with his body, his drugs and a big pile of cash. And, more pressingly, how to escape the hitman who’s been sent to recover Ed’s stash. Soon Jen’s on the run from criminals, corrupt police officers and the prying eyes of the media. Who can she trust? And how can she convince them that the trail of corpses left in her wake are just accidental deaths?

A modern noir that proves, once and for all, the female of the species really is more deadly than the male.

I don’t know why or how I’ve not read this before but I’m bloody glad I have now. Full of unbelievable unfortunate incidents, poor Jen’s life is turned upside down when she finally decides to give her long term loser boyfriend, Ed, the boot. You just … might not expect quite how much. This had me chuckling to myself and racing through the pages like the devil was at my heels. If you want to find out why, you can grab a copy of the book here.

…

The Proposal – S.E. Lynes

‘The first thing you should know, dear reader, is that I am dead…’

Teacher Pippa wants a second chance. Recently divorced and unhappy at work, she uproots her life to renovate a beautiful farmhouse in the countryside, determined to make a fresh start. But Pippa soon realises: your troubles are never far behind.

When Pippa meets blue-eyed Ryan Marks, he is funny, charming, and haunted by his past. He might just be the answer to all her problems. But how well does she really know him?

She knows the story of his life, the pain that stays with him, the warmth of his smile and the smell of his skin. She knows he can make her laugh over a glass of wine.

Pippa can tell truth from lies. She’d know if she were in danger. Wouldn’t she?

That’s a humdinger of an opening line don’t you think? Never let a stranger in your house, that is what I’ve learned from this book. (To be fair, I seldom let people I know in the house because I’m antisocial but that’s another story). Oh, yes, and be very wary of teachers turned romance authors … This is a psychological story of obsession, written in an intriguing style and littered with literary references that will make enlightened readers smile and now knowingly. I’ll be reviewing as part of the tour but for now you can order a copy of the book here.

…

Not too shabby that, five books. Anyone would think I had nothing better to do … Busy week on the blog. Recap below.

The Hangman’s Hold by Michael Wood

Bellevue Square by Michael Redhill

Fractured by Billy McLaughlin

Bye Baby Bunting by Tannis Laidlaw

Truth and Lies by Caroline Mitchell

The Not So Perfect Plan to Save Friendship House by Lilly Bartlett

Return to the Little Cottage On the Hill by Emma Davies

The Other Victim by Helen H Durrant

The week ahead is a little quieter. But then i’m going to be busy personally so perhaps not a bad thing. Three tours in the offing, The Body on the Shore by Nick Louth; Overkill by Vanda Symon; and After He Died by Michael J Malone.

Hope you have a lovely week all. I am in count down mode now as it is less than three weeks until Bloody Scotland. Cannot wait.

See you next week.

Jen

Rewind, recap: Weekly update w/e 02/09/18 That's got you wondering hasn't it? Well ... this is nowt to do with me going for a run.

0 notes

Text

WHO HAS THE AUTHORITY TO TEACH SPIRITUALITY

CHALLENGE TO SPIRITUAL AUTHORITY

by Terrell, J. D.

There is no single matter which more urgently requires a clear perception by the Lord's people than the issue of spiritual authority. The range and immediacy of the challenges presented to the authority of biblical Christian faith are

Alarming.

The basis of that authority has already been spelled out in the opening month of our centenary year - the Inspired Word. For the believer in Christ whose desire is to follow Him, the heart and essence of everything is the Word incarnate, revealed by divine decree in the written word, and illuminated by the Lord the Spirit. Only a recorded revelation of God and by God, inerrant and all-authoritative, can meet and surmount the force and variety of the challenges presented to it in the world of the twentieth century. For this is ultimately where all the challenges to spiritual authority are targetted. The men "who turned the world upside down" did so with the great commission of Matthew 28:18-20 ringing in their ears - "all authority ... given unto Me ... go ye therefore and make disciples". Their conviction was unshakeable that their message was a divine revelation ~ph. 3:3-11; 1 Cor. 2:9-10); they were Spirit-taught and led (1 Cor. 2:13); they had the Word of God (1 Thes. 2:13); and that spelled TRUTH (2 Thes. 2:13).

We shall not attempt to reiterate further the fundamental principles on which the final authority of Scripture is securely based. Its application to the basis of Christian testimony has already been addressed in our May issue. Rather we shall turn briefly to identify the main areas of challenge which the twentieth century has seen develop apace in both subtlety and stridency.

The various challenges mounted against spiritual authority in the past century have changed more in emphasis than in essential nature. They always have been and always will be seen in one of two guises. The first is religious and the second secular. The first partakes of the adversary's earliest of all challenges, "Hath God said?"; the second either joins with the fool of the psalmist's lament and declares, "There is no God", or with equal arrogance, pronounces, "These be thy gods". The enemy of souls plays both cards with equal subtlety and malignity. The individual with some spiritual sensitivity will become the target of authority rejection in the religious sphere, while the carnal or naturally sceptical person falls easier prey to the secular distractions.

Challenges Religious