#sontag spiral

Text

Gelena Pavlenko

* * * *

“Poetry must be: exact, intense, concrete, significant, rhythmical, formal, complex.”

— Susan Sontag, Reborn: Journals and Notebooks, 1947-1963

[exhaled-spirals]

39 notes

·

View notes

Note

Thoughts on swearing in non-fiction?

The performative Millennial swearing that infests even the titles of popular nonfiction books is annoying because it's supposed to signify rebellion or impiety when it actually demonstrates that a battle against older forms of propriety has long been won. They want credit for being rebels while actually conforming. I even have a passage making fun of this in Major Arcana:

Ash del Greco knew the average office girl she saw online, the one working in what they called corporate and living in an SF or Chicago high rise, a girl who seemingly slid from the womb with her yoga mat under one arm and matcha latte in the other hand, the type who had thousands of extra dollars to spend on psychotherapy, mindfulness coaches, wellness retreats, moleskine notebooks, and a color-organized library of sassy self-help books with bright spines, all of them titled some variation on Girl, F*ck This Sh*t: How to Maximize YOUR Bad*ss Life, wasn’t going to listen to a gender-struck teen with a spiral scar on xir big ugly face broadcasting from the dark and cracking wise about the sinking of the Pequod.

Such people would never violate the new proprieties, which is fine—I don't violate them either—but neither will they defend propriety as such. In Light in August, Faulkner abbreviates with a period a word we are now permitted to spell out: "fucking." On the other hand, he spells out a word—a racial epithet—we are obliged to abbreviate. I've often thought they could reissue the novel with this self-censorship reversed. To me, this proves that some words or other in a language are always taboo—literally unspeakable in any context, not even available for quotation or permissible in fictional dialogue.

Aside from that, though, I'd consider it as part of a broader question about how close to speech one's prose style should get. I personally tend to prefer a more "elevated" or artificial style, somewhat campily and ironically so in fact, as I learned it from writers like Harold Bloom and Christopher Hitchens and Susan Sontag, who liked to play up their acquisition of a "class" manner they hadn't been born into, and I therefore tend to find excessively conversational styles patronizing, or else the slumming gesture of someone who was to the manner born. If you can make it work, though, then go for it.

With the aforementioned vanquishing of older models of propriety, many swearwords have retreated to neutrality, the downscale sting and earthy tang gone from the Anglo-Saxon. Sometimes, if one isn't using them (as the Millennial writers do) to convey a now-nonexistent shock or intensity, they can just read as commonplace language, calling shit "shit" the way Chaucer did when the language was new.

youtube

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

2001: A Space Odyssey still leaves an indelible mark on our culture 55 years on

by Nathan Abrams, Professor of Film Studies at Bangor University

2001: A Space Odyssey is a landmark film in the history of cinema. It is a work of extraordinary imagination that has transcended film history to become something of a cultural marker. And since 1968, it has penetrated the psyche of not only other filmmakers but society in general.

It is not an exaggeration to say that 2001 single-handedly reinvented the science fiction genre. The visuals, music and themes of 2001 left an inedible mark on subsequent science fiction that is still evident today.

When Stanley Kubrick began work on 2001 in the mid-1960s, he was told by studio executive Lew Wasserman: “Kid, you don’t spend over a million dollars on science fiction movies. You just don’t do that.”

By that point, the golden age of science fiction film had run its course. During its heyday, there was a considerable variety of content within the overarching genre. There had been serious attempts to foretell space travel. Destination Moon, directed by Irving Pichel and produced by George Pal in 1950, and, in mid-century, Byron Haskin’s Conquest of Space both fantasised space travel and, in Haskin’s film, a space station, which Kubrick would elaborate on in 2001.

youtube

Most 1950s science fiction films, though, were cheap B-movie fare and looked it. They involved alien invasions with an ideological and allegorical subtext. They were cultural, cinematic imaginations of the danger of communism, which in the overheated political atmosphere of the time was seen as an imminent threat to the American way of life.

The aliens in most science fiction films were out simply to destroy or take over humanity; they were expressions, to use the title of a Susan Sontag essay, of “the imagination of disaster”. There were some exceptions, including Byron Haskin’s film version of The War of the Worlds and Robert Wise’s The Day the Earth Stood Still.

By 1968, then, as the lights went down, very few people knew what was about to transpire and they certainly were not prepared for what did. The film opened in near darkness as the strains of Thus Spake Zarathustra by Richard Strauss were heard. The cinema was dazzled into light, as if Kubrick had remade Genesis.

The subsequent 160 or so minutes (the length of his original cut before he edited 19 minutes out of it) took the viewer on what was marketed as “the ultimate trip”. Kubrick had excised almost every element of explanation leaving an elusive, ambiguous and thoroughly unclear film. His decisions contributed to long silent scenes, offered without elucidation. It contributed to the film’s almost immediate critical failure but its ultimate success. It was practically a silent movie.

2001 was an experiment in film form and content. It exploded the conventional narrative form, restructuring the conventions of the three-act drama. The narrative was linear, but radically, spanning aeons and ending in a timeless realm, all without a conventional movie score. Kubrick used 19th-century and modernist music, such as Strauss, György Ligeti and Aram Khachaturian.

Vietnam

The movie was made during a tumultuous period of American history, which it seemingly ignored. The war in Vietnam was already a highly divisive issue and was spiralling into a crisis. The Tet offensive, which began on January 31 1968, had claimed tens of thousands of lives. As US involvement in Vietnam escalated, domestic unrest and violence at home intensified.

Increasingly, young Americans expected their artists to address the chaos that roared around them. But in exploring the origins of humanity’s propensity for violence and its future destiny, 2001 dealt with the big questions and ones that were burning at the time of its release. They fuelled what Variety magazine called the “coffee cup debate” over “what the film means”, which is still ongoing today.

The design of the film has touched many other films. Silent Running by Douglas Trumbull (who worked on 2001’s special effects) owes the most obvious debt but Star Wars would be also unthinkable without it. Popular culture is full of imagery from the film. The music Kubrick used in the film, especially Strauss’s The Blue Danube, is now considered “space music”.

Images from the movie have appeared in iPhone adverts, in The Simpsons and even the trailer for the new Barbie movie.

The warnings of the danger of technology embodied in the film’s murderous supercomputer HAL-9000 can be felt in the “tech noir” films of the late 1970s and 1980s, such as Westworld, Alien, Blade Runner and Terminator.

HAL’s single red eye can be seen in the children’s series, Q Pootle 5, and Pixar’s animated feature, Wall-E. HAL has become shorthand for the untrammelled march of artificial intelligence (AI).

In the age of ChatGPT and other AI, the metaphor of Kubrick’s computer is frequently evoked. But why when there have been so many other images such as Frankenstein, Prometheus, terminators and other murderous cyborgs? Because there is something so uncanny and human about HAL who was deliberately designed to be more empathic and human than the people in the film.

In making 2001, Stanley Kubrick created a cultural phenomenon that continues to speak to us eloquently today.

#movies#science fiction#2001: a space odyssey#stanley kubrick#space#technology#artificial intelligence#space exploration#tet offensive#featured#Youtube

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

X-MEN in other media (TV, films, video game cinematics)

Characters By Screen Time

James “Logan” Howlett / Wolverine - 996:30

Scott Summers / Cyclops - 517:15

Professor Charles Xavier / Professor X - 514:45

David Haller / Legion - 443:30

Dr. Henry “Hank” McCoy / Beast - 361:30

Jean Grey / Phoenix - 350

Anna Marie / Rogue - 305:15

Ororo Munroe / Storm - 276:45

Sydney Barrett - 269

Erik Lehnsherr / Magneto - 261

Reed Strucker - 199:15

Kitty Pryde / Shadowcat - 198:15

Kurt Wagner / Nightcrawler - 195:30

Dr. Caitlin Strucker - 194:45

Lorna Dane / Polaris - 193:15

Marcos Diaz / Eclipse - 183:15

John Proudstar / Thunderbird - 175

Raven Darkholme / Mystique - 174:15

Emma Frost / White Queen - 172

Lauren Strucker - 166:15

Wade Wilson / Deadpool - 156:30

Andy Strucker - 148

Clarice Ferguson / Blink - 144:15

Jubilation Lee / Jubilee - 138:45

Remy LeBeau / Gambit - 133:30

Amahl Farouk / Shadow King - 125:30

Jace Turner - 103:15

Cary Loudermilk - 98

Dr. Melanie Bird - 96

Piotr Rasputin / Colossus - 83:15

Kerry Loudermilk - 80

Ptonomy Wallace - 75:45

Bobby Drake / Iceman - 73:30

The Stepford Cuckoos* - 71:15

Evan Daniels / Spyke - 69:30

Victor Creed / Sabretooth - 69:15

Pietro Maximoff / Quicksilver - 68:45

Lenny Busker - 68:30

Dr. Oliver Bird - 66:15

Dr. Moira MacTaggert** - 65:45

Hisako Ichiki / Armor - 65:45

Yukio - 61:15

En Sabah Nur / Apocalypse - 55:45

Mortimer Toynbee / Toad - 55:15

Wanda Maximoff / Scarlet Witch - 53:45

Warren Worthington III / Angel - 54

Lucas Bishop - 53:30

Clark DeBussy - 52:15

Dominic Petros / Avalanche - 51:30

Switch - 49:30

Mariko Yashida - 47:30

Fred J. Dukes / Blob - 47:15

Nathan Summers / Cable - 47

Laura Kinney / X-23 - 45

Gabrielle Haller - 44

Dani Moonstar / Mirage - 43

Reeva Payge - 40

Samuel Guthrie / Cannonball - 38:45

Amy Haller - 38:15

Alex Summers / Havok - 37:15

Forge - 34

Sean Cassidy / Banshee - 32:30

Cain Marko / Juggernaut - 32:30

Nathaniel Essex / Mr. Sinister - 31:30

William Stryker - 31:15

Arkady Rossovitch / Omega Red - 30:30

Sebastian Shaw / Black King - 30:15***

Senator Robert Kelly - 30

Rahne Sinclair / Wolfsbane - 28:30

Sonia Simonson / Dreamer - 28:15

Tabitha Smith / Boom Boom - 27:45

Erg - 27:45

Amara Aquilla / Magma - 27:15

St. John Allerdyce / Pyro - 25:45

Angelo Espinosa / Skin - 25:15

Roberto Da Costa / Sunspot - 25

Shingen Yashida - 25

Abigail Brand - 24:45

Illyana Rasputin / Magik - 23:15

Jason Wyngarde / Mastermind - 23:15

Dr. Roderick Campbell - 23

Kevin Sydney / Changeling/Morph - 22:30

Neena Thurmon / Domino - 21:15

Kevin MacTaggert / Proteus - 21:15**

Hideki Kurohagi - 20:45

Bolivar Trask - 20:15

Russell Tresh - 20

Danger - 19:15

Koh - 17:45

Caliban - 17:30

Tessa / Sage - 17:15

Yuriko Oyama / Lady Deathstrike - 17

Walter - 16:30

Donald Pierce - 15:15

Mojo - 15

Ichiro Yashida - 14:45

Kikyo Mikage - 14:45

Empress Lilandra Neramani - 14:30

Fabian Cortez - 14:30

Dr. Cecilia Reyes - 14:30

Silver Fox - 14

Christopher Summers / Corsair - 14

Sauron - 14

Betsy Braddock / Psylocke - 13:45

Jamie Madrox / Multiple Man - 13:30

Min - 13:30

Sarah / Marrow - 12:45

Ray Crisp / Berzerker - 12:45

Kenuichio Harada / Silver Samurai - 12:30

Vuk - 12

Ord of the Breakworld - 11:45

Ellie Phemister / Negasonic Teenage Warhead - 11:30***

Warlock - 11:30

Callisto - 11

Christoph Nord / Maverick/Agent Zero - 11

Shard - 11

Glow Worm - 10:45

Warren Worthington II - 10:30

Nick Fury - 10:15

Spiral - 10:15

Graydon Creed - 10:15

Vadhaka - 10:15

Longshot - 10

Ka-Zar - 10

Arkon - 10

Jimmy / Leech - 9

Steve Rogers / Captain America - 8:15

Vincent / Mesmero - 8:15

Lockheed - 8

Peter Gyrich - 8

Amelia Voght - 7:30

Dr. Kavita Rao - 7:30

Kruun - 7:30

Kallark / Gladiator - 7:15

Shakari - 7:15

Shatter - 7

Mondo - 7

Dr. Abraham Cornelius - 6:45

Cameron Hodge - 6:45

The Phalanx - 6:15

Aghanne - 6:15

Philippa Sontag / Arclight - 6

D’Ken - 6

Vertigo - 5:45

Julian Keller / Hellion - 5:45

Cassandra Nova - 5:30

Fade - 5:30

Edward Tancredi / Wing - 5:15

Solar - 5:15

Monet St. Croix / M - 5

John Grey - 4:45

Samuel Paré / Squidboy - 4:45

Selene Gallio - 4:30

Alison Blair / Dazzler - 4:15

Nimrod - 4:15

Zaladane - 4:15

Heather Hudson - 4:15

John Wraith - 4:15

Black Tom Cassidy - 4

Zebediah Killgrave - 4

Harry Leland - 3:45

James Hudson / Vindicator - 3:45

Immortus / “Bender” - 3:45

Arcade - 3:45

Annalee - 3:45

Megan Gwynne / Pixie - 3:30

High Evolutionary - 3:30

Master Mold - 3:30

Trevor Fitzroy - 3:30

Gorgeous George - 3:30

Shiro Yoshida / Sunfire - 3:15

Vanisher - 3:15

Ape - 3:15

Mark Hallett / Sunder - 3

Zabu - 3

Ruckus - 3

Hairbag - 3

Slab - 3

Tildie Soames - 3

Ruth Aldine / Blindfold - 2:45

Bella Donna Boudreaux - 2:45

Bantam - 2:45

Irene Adler / Destiny - 2:30

Sebastion Gilberti / Bastion - 2:30

Dr. Carol Hines - 2:15

Garrok - 2

Hepzibah - 2

Agatha Harkness - 2

Cal’syee Neramani / Deathbird - 1:45

James Proudstar / Warpath - 1:30

Sooraya Qadir / Dust - 1:30

Guido Carosella / Strong Guy - 1:30

Elaine Grey - 1:15

Jean-Paul Beaubier / Northstar - 1:15

Dr. Michael Twoyoungmen / Shaman - 1:15

Jeanne-Marie Beaubier / Aurora - 1

Walter Langkowski / Sasquatch - 1

* Sometimes it’s not possible to tell which of the sisters are on screen in any given shot, so I’m just making one calculation for when any of them are on screen. I don’t like it, but it’s the best accurate option I have.

** Includes the Sasaki characters from the anime. Yui is just Moira with a different name, and Takeo is somewhat David but more Kevin, so I’m counting him towards Kevin.

*** Includes their appearances as illusions in Emma’s mind in Astonishing X-Men.

IMDB listing

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

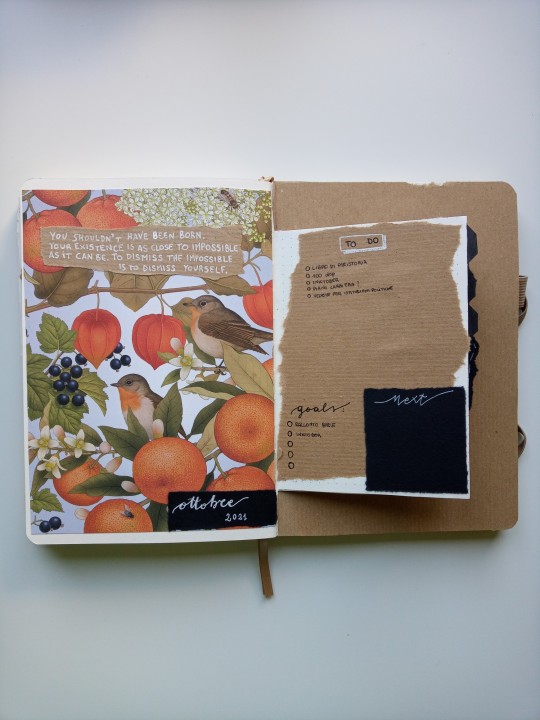

October monthly spreads (inspired by x)

19|09|2021

14/100 days of productivity

Today I decided not to study. It was a last minute decision, due to the fact that last night I didn’t feel great, which resulted in me sleeping more this morning, and waking up with not so much energy. I decided to embrace it as a day off to do something else. I really needed distraction, so I listened to audiobooks of stoires by H.P. Lovecraft while creating these spreads in my bullet journal. After seeing the post linked above a couple of days ago I decided to try out something similar in my own journal, to change things up a bit, and I am enthusiastic about how it turned out. The short stoires I have listened to while working on this are The Temple (which was a re reading for me, but I liked the story so much the first time than when I saw it in the list of audiobooks I couldn’t resist), The Statement Of Randolph Carter, Beyond The Wall Of Sleep (which I had also re in the past,but I defently enjoyed more this time, not that I have a better knowledge of Lovecraft’s world) and The Transition Of Juan Romero.

The quotes in my bullet journal spreads are:

“You shouldn’t have been born. Your existence is as close to impossible as can be. To dismiss the impossible is to dismiss yourself.” - Matt Haig

"How can I describe my life to you? I think a lot, listen to music. I’m fond of flowers."- Susan Sontag

“All morning it has been raining.

In the language of the garden, this is happiness.” - Mary Oliver

“I wish I wrote the way I thought

Obsessively

Incessantly

With maddening hunger

I’d write to the point of suffocation

I’d write myself into nervous breakdowns

Manuscripts spiralling out like tentacles into abysmal nothing “ - Benedict Smith

#wasn't the most productive day but i am still happy about what i did giving i am not super energetic#studyblr#studyinspo#100 dop#100 days of productivity#bullet journal#bujo#bullet journal spread#bullet journal monthly spread#monthly spread#journal#mine#notebook#myhoneststudyblr#serendistudy#lookrylie#journaling#the---hermit

185 notes

·

View notes

Text

End of Year Review

thank you my beloved @attempted--eloquence for the tag :)

What fandoms did you create for ?

only teen wolf works published, but my wips have some others

How many works did you make this year? Fics (posted on ao3 or tumblr or wherever), edits, gifsets, moodboards, playlists, fanart, vids, meta?

20 fics, probably a couple gifsets. did Not expect the number to be that high because it feels like I haven't been writing a lot recently, but hey! a pleasant surprise :)

Any stats you wanna tell us about?

managed to make it to 300k words this year :) which is SO weird to think about but !!!!! so glad I took the leap last year to start writing again, it's been a Blast

What inspired you this year? Any specific works or creators?

read a lot during quarantine: ocean vuong, susan sontag, anne carson, others. read shitty romance novels, watched comfort movies. met great people, made phenomenal friends, got into a relationship.

regarding specific creators!! love spiraling w/ my love @chcrrysprite and my favorite writing partner @attempted--eloquence, my girl @ttp5000, and the man who runs through full literary analysis with me and i love him for it @thecenturiestrickle. they're all completely unhinged and i love them with my whole heart

okay I wanted to do like an appreciation post at some point during the year but it just Sat there in my drafts, so we're gonna do it here. here are some works/creators that really inspired me! and recommendations, i guess, to anyone who needs them--

every time i read @eneiryu i'm in genuine and complete awe. they weave words together and worldbuild like i've never seen before. the expedition set out to chart the distance from me to you ruined my whole entire life but, like. in the best possible way.

every time i read @spikeface, i feel like i'm going feral. i read the boy who swallowed the earth last night and it felt like the world was coming apart at the seams and me along with it. no one writes scott like they do. would also Highly recommend the family of things because it makes me feel like i'm losing my mind in the best possible way.

anything by @thecenturiestrickle will make you think a lot about society and interpersonal relationships. everything he's written hurts a lot because he's mean but i like Gather Back All That Dawn Has Put Asunder for the ruminations on growth.

no one does introspection quite like @chcrrysprite. would recommend her entire bibliography, but if i had to pick one from this year, where the spirit meets the bones will make you cry like a baby

everything @attempted--eloquence writes is genuinely award worthy. i don't even know where to begin. staking claim to the mess you've made has inspired SO many of my theo thought tangents. so has Still waiting for the end of the world, leave a message when it comes. Handle With Care, obviously, is a fandom classic. and the 2 of us poured a Lot of love into in time of daffodils who know.

@honeyscapes's Inglorious Roommates is so, so good. i've been binging published romance novels in the past week and nothing has come CLOSE to the chemistry and relationship development they've managed.

Quintessentia is phenomenal with language and characterizations. everything i've read from them makes me feel well and truly breathless. would highly recommend my skin's smothering me, help me find a way to breathe.

Teen Wolves by nothoughts_headempty is written in script format and is the season 7 we deserved. genuinely 10/10, they should have replaced the scriptwriters.

been going by a non-name by dramaticgasp haunted me for days.

@hidesourcheeks legally owns scallisaac, i think. or at least they should. Better to Die on your Feet is a scallisaac hunger game au that I would take Any Day over either canon, because Oh My God. Who Are You, Really? is an allison pov and also the best allison-centric thing i've read in my entire life? canon WISHES it could have that much character exposition. and while i'm here, i might as well recommend On the Side of Caution, their isaac-centric piece. screaming and crying and throwing up because i have Never seen something that un-romanticizes beacon hills so beautifully

not yet a corpse but still, he rots by @yikeshereiam because [screams into the void] angsty theo introspection!! also i've never read a sentence by them that hasn't knocked the breath out of me

that's all i'll give for now. there are definitely some i'm missing. might fuck around and make a rec list

What are you most proud of?

i had so much going on in the spring and somehow still managed to write a Lot?? also did my first collab (daffodils) wrote my first thiayden fic (which i've been wanting to for a Long Time!), wrote my first non-tw fic (should be posted soon :) ) and experimented with a new writing style. i feel like my growth is visible from the beginning of the year to the end, and i'm so, incredibly happy about it. also, the college au?? it started out as a christmas gift last year and then Completely took on a life of it's own.

What’s a piece you didn’t expect to make? Why?

Daffodils w/ bee :) never expected to collab, but i am Inordinately pleased with the results. it was so, so fun to work together

What are you excited to work on next year?

super excited to finish a multichapter fic for once!! i've been working on yofoe again recently :) planning to finish it this year! i would like to finish at least one of the thiaydens i started, and hopefully some of the others. keep an eye out for a regency au :) and when I finish yofoe, there's a chimera pack fic that i've been wanting to write for literal MONTHS but i've been holding myself back because i knew i didn't have the time. well. now i do :) also. ratatouille thiam, because chef theo is my weakness.

tagging @chcrrysprite and @thecenturiestrickle

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

no end in sight (7/7)

Fandom: World of Warcraft

Pairing: Jaina Proudmoore/Thalyssra

Rating: T

Wordcount: 4,145

Summary: Jaina goes to Suramar seeking aid after leaving the Kirin Tor. An AU exploring the events post-Theramore and Jaina’s recovery during Legion.

Read it here on AO3 or read it below the cut

“But the landscape of devastation is still a landscape. There is beauty in ruins.”

— Susan Sontag, from ‘Regarding The Pain Of Others’

--

“You will get used to it,” they told her. “Eventually.”

Jaina did not believe them.

The enchanted wrappings were gone, but some days she still felt like an Ethereal. It was something about the ground. Sometimes, even a week after her body had been fully healed, it felt as though the earth did not exist beneath her feet. As though she walked upon a pane of glass above the distant drop of the void far below.

She no longer felt an uncomfortable rush of mana when she stood on leylines, but she still avoided stepping on them for the first week. It was an automatic reaction she could not control, flinching when she expected to be burned. Jaina could not tell if this was made better or worse by the fact that she could no longer physically see the leylines. She could sense their vague location, but it was more like the buzz of a mosquito forever flitting just out of sight.

“Oh, that’s just how it is for us,” Valtrois said when Jaina questioned her about it.

They were standing over a darkened teleportation pad in Oculeth’s corner of Shal’Aran. Oculeth himself was on his hands and knees, attempting to repair the teleportation pad, which had gone dark the day before without warning, the portal anchored above it winking out of existence with a splutter. Jaina and Valtrois had their hands full of various tools, but weren’t paying any attention to what he was doing.

Jaina still wore the enchanted mask. Shal’Aran was bustling with more people than ever. And now that the Nightborne had a reliable cure to mana addiction, the final fight against the Legion began in earnest. Whispers of the Dusk Lily’s insurrection grew into murmurs, grew into shouts, grew into warsongs. High ranking members of both the Horde and Alliance flooded to Suramar daily.

For all her talk to Farodin about choosing sides, Jaina still hadn’t picked hers openly.

“Us?” Jaina repeated. Wordlessly, Oculeth held out his hand, and she placed a mote extractor into it. His fingers closed around the handle, and he continued working with the instrument.

“Us. Nightborne. And, well -” Valtrois gave Jaina the once-over with her gaze. “-whatever you are now.”

“Alive,” Oculeth supplied helpfully. Though he did not look up, he did give the mote extractor a little wave for emphasis.

“She was never dead to begin with.” Valtrois took the mote extractor and replaced it with a scoped barrel forged from leystone ore.

“Technically -”

“No, not even technically,” Valtrois snapped waspishly.

“Technically,” Oculeth continued, undeterred. He mounted the scoped barrel into a hollow section of the transportation pad made by disassembling its metal facing. “One could make the argument that she was neither living nor dead when she was an Ethereal.”

Valtrois looked at Jaina and her voice was flat. “Don’t listen to him. You were always alive.”

All too well Jaina remembered what it had felt like. It hadn’t been that long ago, after all. The sensation of drifting through space and time like an unquantifiable entity, untethered by death or physical feeling.

In a way, she agreed with Oculeth, but she certainly didn’t say that aloud. Mostly because she didn’t want to think about it too hard herself.

A thought struck her, and she said, “And what about now?”

At that, both Oculeth and Valtrois peered at her with curious expressions. Oculeth had paused in his work to answer, “I would wager you’re very much alive, Lady Proudmoore.”

“No, I mean -” Jaina had to pause to collect her thoughts and place them all in neat order. “Nightborne and humans have vastly different lifespans, but you said it yourself: I’m neither here nor there, so to speak. So, what happens now?”

For a moment, neither of them responded. Then, Valtrois tapped an instrument against her opposite hand and said, “The inscriptions make it so that your physical body acts the same way the enchanted wrappings do for Ethereals. They both contain your energy, channel it, and stop your body from further deterioration.”

“Which,” Oculeth added, his words slow and thoughtful, “could also refer to aging. We can’t be sure for certain how long you will live now. As long as other Nightborne? I doubt it.”

“But longer than any human,” Valtrois said.

“Oh, without a doubt,” he agreed. “Could I please have the -? Thank you.”

Valtrois handed him a vial of what appeared to be thick, viscous demon’s blood. It burned with fel-green energy and stank of sulfur when he unstoppered the vial and poured a few drops of its contents down the hollow leyline barrel. The interactions between them were, as always, comfortable. They moved with an ease in each other’s presence, the same way they did with Thalyssra and even with Jaina.

They were the same people, Jaina knew. They moved, acted, and sounded the same, but they looked so completely different. It had been nearly two weeks now since Jaina had been unwrapped and declared stable, and still she had a difficult time reconciling the fact that these people were the same Valtrois and Oculeth who had dragged her into one of the most genuine friendships she’d formed in -- well. Far too long.

Not to mention Thalyssra. But that was different again.

Jaina pushed that nascent thought aside very quickly. Thalyssra was too busy for any sort of nonsense these days. Which is what that sort of dreadful, sinking hope was: nonsense. Nothing good would come of it, Jaina was sure.

There was no getting used to this. She kept waiting for the other shoe to drop. This was an unreal existence. She peered around every corner as if expecting something to leap from the shadows. She encountered every good fortune with suspicion. Hope was dangerous. Hope was frightening. Hope had failed her in the past. Hope was not something she had ever thought to feel again. Certainly not like this.

“Is everything alright?” Valtrois asked.

Jaina started. It took her a moment to realise that Valtrois was not speaking to her but to Oculeth.

He removed the barrel from the ground, setting it and the vial aside so that he could study the dismantled teleportation pad and scratch at the top of his head. “On this end everything is fine, but that’s precisely what worries me. It means Thalyssra was right. The teleporter for the Waning Crescent was intentionally tampered with on the other side.”

Valtrois sighed out an elegant and exaggerated, “Fuck.”

“My thoughts exactly.”

“So, who did it?” Jaina asked.

Oculeth began putting the teleportation pad back together, sliding the heavy metal plate back into place. “I have an inkling, but we should send one of our Horde friends to investigate inside the city itself. Valtrois, would you update Thalyssra and ask if -?”

“Already on it.” Valtrois was walking towards Oculeth’s heavy work station, and placed the tools she had been holding atop the desk. She did not bother lining them up neatly. She made an abortive movement towards the stairs spiraling beneath the arcan’dor, but stopped. Suddenly, she whirled about, her eyes narrowed, and pointed at Jaina. “Don’t go anywhere. You’re not allowed to leave without saying goodbye.”

Jaina blinked, taken aback. “I wasn’t planning on it.”

Valtrois gave her a knowing look.

Shifting her weight between her feet, Jaina added guiltily, “Not anymore, at least.”

With a suspicious grunt, Valtrois said to Oculeth, “Fix her with a tracking beacon.”

“I said I wouldn’t!” Jaina insisted, indignant.

“That won’t be necessary,” Oculeth said, affixing magnetic bonds to the teleportation plate so that it stayed put.

“Thank you!” Jaina said.

“Those leyline inscriptions of hers have a unique enough magical signature. She’s like a piece of the Nightwell floating around, and -- once known -- that signature could pinpoint her in a crowded street.”

“Good,” Valtrois said, turning to leave once more.

Jaina opened her mouth to protest, but whatever she had been about to say died on her lips. She glanced down at the back of one hand. The runic markings etched into her skin gleamed, infused with their own silvery light that pulsed with every heartbeat.

Ever since the arcane wrappings had been removed, she no longer endured headaches or itching. She could cast spells of any calibre without threat of self-collapse, a theory which she had tested only a few days ago, when she and Thalyssra had gone just south of Moonguard Stronghold for precisely that purpose. Nothing out of the ordinary had happened, and Jaina’s spellcasting had felt exactly as it had before the destruction of Theramore. Apart from the heightened sensation of mana flowing through every vein, as if the procedure now made her aware of even the barest trace of arcane energy within herself. And perhaps it did.

Oculeth rose to his feet and dusted off his hands. Valtrois had descended the stairs in search of Thalyssra, leaving him and Jaina in relative solitude. As alone as anyone got in Shal’Aran these days.

His usual smile was gone, but there remained a softness around his keen eyes. “You could veil your magical signature so that nobody would be any the wiser. I could teach you, but it would require you to maintain concentration for that duration of the effect.”

Jaina considered that, then shrugged. “So long as you’re the only people who know it, I don’t mind.”

That familiar smile of his returned, but it was small. “Have you asked Thalyssra about why she chose these particular designs for your tattoos?”

“No.” She moved to set down the instruments she was holding beside those Valtrois had dumped atop the workbench. Except Jaina did it with far more care for the instruments themselves. “Does it matter?”

Oculeth answered with a noncommittal hum. “Physiologically speaking? Not a whit. Socially speaking? In vast amounts.”

He moved to stand beside her, and she allowed him to gently take her hand. He lifted it between them. He brushed his thumb against the tattoo on the back of her hand, nudging the cloth of her sleeve up her arm to reveal where the inscriptions wove along her wrist. His own markings stood out against his skin, the contrast stark in comparison to Jaina’s paler complexion.

“To my people, these are signs. Signifiers.” Oculeth dropped her hand. “You’ve been branded. Wouldn’t you like to know what it means?”

Jaina’s fingers curled into a fist. She had to force her hand to unclench. “I’ll be sure to ask next time.”

--

That was only somewhat of a lie. Jaina was too afraid to broach the topic. In the rare occasions where she screwed her courage to the sticking place, Thalyssra always appeared so busy. Jaina would approach during the day to find Thalyssra engaged in deep conversation with Champions of the Horde and Alliance. During the evening, Jaina stood in the doorway to Thalyssra’s private study two floors beneath the bustle of Shal’Aran, and Thalyssra would be hunched over her desk, so entrenched in her work that she would not notice Jaina’s presence hovering behind her. Once, Jaina found Thalyssra sleeping at her desk, head pillowed by an open book. She still had a quill held loosely between her fingers.

Jaina let her be. Thalyssra did not need any interruption to her already hectic life, what with all the rebel-rousing and insurgency.

It was a flimsy excuse, even by her standards. But Jaina clung to it nonetheless.

That being said, it was a difficult excuse to cling to when Thalyssra approached her instead.

“I’ve been saving this for a special occasion.” Thalyssra held a bottle of arcwine in her hands. It was one of the same bottles that Jaina had brought back from the Twilight Vineyards. That felt like so long ago. “Will you join me?”

Jaina hesitated. She was currently helping Valtrois pass out fruit of the arcan’dor to new arrivals at Shal’Aran. Before she could say anything however, Valtrois took the basket of fruit from her hands and said, “Go. I can do this by myself.”

Jaina went.

“If you don’t want to we can -” Thalyssra started to say, but Jaina shook her head with a smile.

“No, no. A glass of wine sounds lovely.”

Jaina started towards the stairs, assuming they would be heading down to Thalyssra’s private study, only for a hand on her arm to stop her.

Thalyssra tilted her head. “This way. I thought we might go outside for a change. It’s a warm evening.”

They walked towards the teleportation pads in a corner of Shal’Aran. Oculeth was conspicuously absent, his tools lying about. The portal to the Waning Crescent had been restored, but another portal had been sectioned off with a length of silk rope.

Thalyssra ducked beneath the rope barrier. “I asked Oculeth to restrict traffic through this one temporarily.”

And without further explanation, she stepped through the portal. Jaina lingered for a moment. Steeling herself, she followed.

The ruins of Elune’eth overlooked the valley of Meredil. In the distance, the spires of Suramar raked the sky, the Nightwell’s tower foremost among them. The shield surrounding Suramar shimmered in the early evening light like a soap bubble, transparent yet full of colour.

It was indeed a lovely, warm evening. Spring had draped itself across Suramar. New green shoots broke the loam, and the trees were flowering, purple and white. Thalyssra crossed over to a fallen pillar stretched along the ground and strewn with violet-veined ivy.

Jaina blinked. Cushions, and wineglasses, and a plank of light food had already been artfully arranged. Either Thalyssra did not notice her hesitation, or chose not to react, for she sat facing the city view, and unstoppered the wine.

“I don’t know if you realised,” Thalyssra said without turning around. “But you stole a fine vintage for us that day. This has been aged for no less than four centuries.”

They were alone. Jaina cast a quick glance around before removing her mask. Then she moved to sit beside Thalyssra, folding her legs, cross-legged, upon the cushions. She picked up a glass and held it out for Thalyssra to pour the wine. The mask she left on the ground, forgotten. “So, what’s the occasion?”

“The beginning of the end.” Thalyssra poured one glass, and then the other. She gave the bottle a little twist as she stopped pouring, so as not to spill a single drop. She set the bottle aside. “I’ve just received news that good friend and ally has just been rescued from the Terrace of Order. As we speak, the sigil of the rebellion will be flying over his empty cage.”

Despite the apparent good news, Thalyssra lifted her glass towards Jaina in a mocking salute, before taking a large drink.

Jaina turned her own glass slowly in her hands, rotating it by the delicate stem. “And yet you sound less than thrilled?”

Thalyssra sighed. She stared into the tide-dark wine of her glass. “I am happy, of course. Finally, we have sparked the rebellion into a wildfire. With it however comes a whole host of other worries.”

“Such as?” Jaina sipped at her wine. There was a heady slope of warmth upon the tongue, more like a mulled wine absent the bite of hard winter spices.

Reaching into a pocket -- Light only knew where she kept pockets on an outfit like that -- Thalyssra pulled out a folded letter. “I have a meeting with this archmage of yours.” Thalyssra tapped the closed letter against the bowl of her glass. “What was his name again?”

“Khadgar?”

“Yes. That’s the one.”

Jaina frowned and lifted the glass to her lips for another sip. “How could you not remember his name? I thought you two knew each other.”

The tilt of Thalyssra’s head was inquisitive. “I have never met the man.”

“But -” Slowly Jaina lowered the wine. “That can’t be right. He’s the one who arranged my coming here in the first place. And he said he’d asked you about my condition and whereabouts.”

With a vague wave of her wine glass, Thalyssra said, “I received exactly two letters from the Archmage of the Kirin Tor.” She paused, glancing down at the letter in her hand, then added, “Well, three, actually. If you count the latest correspondence from the warfront.”

“You really just took in a known war criminal without question?”

“Look around,” Thalyssra gestured back towards Shal’Aran, “I’ve surrounded myself with known war criminals. It just depends on who you ask.”

Jaina laughed, soft and incredulous, and shook her head. “I spent so much of my time here thinking that you were only doing this to curry favour with the Kirin Tor and -- I don’t know -- earn some of their resources for your own means.”

“The same way you thought I was playing both the Horde and the Alliance against one another for my own means?”

“Well, weren’t you?”

Thalyssra’s answering smile glinted with a sharp flash of teeth. “Oh, yes. But that does not mean we cannot hold two opposing ideas in our minds simultaneously. Cunning does not preclude compassion.”

Being on the receiving end of that look, Jaina could not stop the flush that heated her cheeks. Perhaps it was the wine. She took another drink. As she did so, Thalyssra gazed out towards the city. Despite her smile earlier, she held her jaw taut.

“You’re worried,” Jaina realised aloud.

Thalyssra did not answer immediately. She stared out across the night-washed land, her expression clearly visible even beneath the shadow cast by her hood. She worried the letter with her fingers, bright and nimble and rapping the folded parchment against her knee again and again.

“I have been many things in life. A mage and a teacher before the Sundering. A coward along with the rest of Suramar during the War of the Ancients. A revolutionary only when no other option was available to me. And none of these things help me be a better diplomat.” Thalyssra snorted, a derisive sound. “Most days I feel like a fraud calling myself a leader. What will Tyrande say? My kin of old remember me as one of the Highborne they fought against so bitterly for so long. Worse, they’ll think of my people as relics, ruins of a time when we were great and noble and just, but no longer. How can I possibly convince them Suramar is worth saving?”

Reaching out, Jaina placed her hand over Thalyssra’s to stop her from fidgeting with the letter. Thalyssra’s nervous movements stilled, and Jaina said, "You convinced me that I was worth saving."

Thalyssra snorted softly. "A task for the legends."

"The stuff of heroes.” Jaina looked down at where she stroked the back of Thalyssra’s hand with her thumb. It was easier than meeting her eyes. Even so, when Jaina spoke she could hardly believe the words that came from her mouth. “Even if I might be able to convince Tyrande to drop a ten thousand year old grudge,” she said, "the Kirin Tor have already proven they aren't willing to listen to me. The Alliance are as dedicated to stopping the Legion as any. If all you need to secure their support is to let them think they will be driving away the Legion and destroying the Nightwell in the process, then -”

Jaina let her voice trail off suggestively. Hesitantly, she glanced up to find that Thalyssra was studying her with a veiled expression. “Lady Jaina Proudmoore, are you encouraging me to use the Alliance with the full intention of joining the Horde?”

“I suppose I am.” Jaina grimaced as though a bad taste lingered on the back of her tongue. She tapped her thumb against Thalyssra’s knuckles in faux admonishment before removing her hand. “Don’t make me say it again, though.”

Thalyssra laughed, and the sound was warm, as warm as her gaze. “You’ve come a long way since first we met.”

“Thanks to you. And Oculeth and Valtrois, I suppose,” Jaina added. “Don’t tell them I said that though.”

“Your secret is safe with me.”

“I know.”

Thalyssra tossed the letter aside to refill her own glass, and held up the bottle towards Jaina in a silent question. Jaina held her glass out to be refilled. For a while all they did was drink in peace and comfortable talk, broken only by moments of easy silence. The wooden plank piled with food diminished, and the blunt little knife perched atop it gathered crumbs.

Night began to sweep towards the dimmed horizon, and far-flung stars dotted the sky. Like this, Thalyssra seemed more in her element than ever, cast all in twilight and dusky hues. It was all too easy to remember her as the withered mimicry of herself from not so long ago.

Jaina caught herself staring, and looked abruptly away. She buried her nose in her glass. Beside her, Thalyssra leaned forward to pluck one of the last dark grapes from its vine upon the platter, and eat it. The tattoos upon her arms gleamed in the early evening light.

Mouth dry despite the drink, Jaina said, “Oculeth told me that I should ask you about my tattoos. Do you know what he meant?”

Thalyssra paused, but it was so small a thing that Jaina wouldn’t have noticed if she had not been watching for a reaction. She seemed to mull over her answer. “I told you once that Nightborne have natural markings that are similar across families. That is true. They are hereditary, but unique. They are demarcations of familial resemblance, like height or hair colour.” She reached out to ghost her fingertips across the markings that glowed on Jaina’s cheek. “These are my family’s markings.”

Jaina’s breath caught in her chest as Thalyssra pulled her hand away. “So, every Nightborne who looks at me will think we’re related somehow?”

“In a sense. From what I understand about humans, Nightborne kinship groups are very different. You might call someone a cousin, but we have specific terminology for everyone’s distinct relation to one another. To call Valtrois my cousin, for instance, would be technically correct, but inadequately descriptive.”

“And what would you call her?”

“There is no exact translation. She is my third cousin’s wife’s sister’s niece on her father’s side but my mother’s side.”

Jaina stared at her. “I swear you just said words right then, but Light knows what they meant.”

That earned a laugh. “It means: you have nothing to worry about. The markings don’t have to mean anything, unless you want them to. After all, what other markings was I supposed to give you? I was always under the impression you were going to leave Suramar after your procedures were finished. How many Nightborne would you ever encounter elsewhere that would make this matter?”

The thought of leaving made Jaina’s stomach clench. When she spoke her voice sounded faint even to her own ears. “I could - I could stay. I could help with your Alliance diplomacy.”

"It's kind of you to offer, but that's not why I would want you to stay."

Jaina looked away. She felt a gentle touch at her chin, turning her back to face Thalyssra. Her head was buzzing with warmth and energy, like the thrum of mana beneath her skin.

“This was a bad idea,” Jaina murmured. “I did not think it would affect me this much.”

“The wine?”

“No,” Jaina breathed. “No, not that.”

Thalyssra had placed her own glass aside. One of her hands still lingered upon Jaina’s chin, and her thumb traced a line just beneath Jaina’s lower lip. “I would have you stay of your own accord. Not because you have nowhere else to go. Not because this is the only path available to you.”

Before she could think about what she was doing, Jaina allowed her own hand to drift up and grasp Thalyssra’s wrist. She did not pull Thalyssra’s hand away, but instead held it in place, maintaining that touch. “I want to. Even for a little while. One day I will have to leave, but until then -”

“You are always welcome here. For as long as you would like.” Thalyssra moved her hand to curl her fingers at Jaina’s jawline, the pad of her thumb brushing the corner of Jaina’s mouth until Jaina almost forgot how to breath.

“I want them to mean something. The markings,” Jaina admitted in a rush. “I don’t know what exactly that entails, but I want it.”

Thalyssra smile. Her eyes were twilit, and her words were soft. “They can mean whatever you like.”

“Thalyssra, if you don’t kiss me already, I swear I -”

She did. And for the first time in a long time, sitting amongst the ruins of an ancient civilisation, this was a place that felt like home.

#jaina proudmoore#thalyssra#first arcanist thalyssra#jaina proudmoore/thalyssra#world of warcraft#roman writes#wow#whew finally got that out of the way

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

The specificity of artistic languages-as voiced by Glenn Gould and Joseph Brodsky

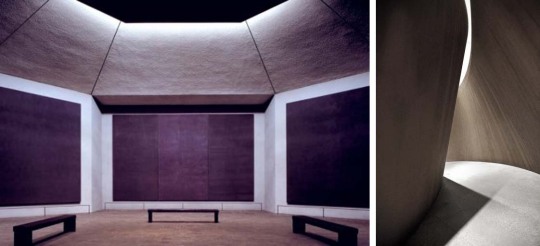

M. Rotchko, Huston, 1971 and R. Serra, Venezia, 2005

It is a pleasure to lend an ear to two megaphones of the caliber of the two artists cited to get at that colossus (of Rhodes?) that bears the name of Marcel Duchamp. It’s been exactly 34 (1) years since I started my battle, but my bullets bounced off a rubber wall rebounding to the sender. I have to thank heaven if I have come out unscathed so far. The thread of the discourse of the two unravels very clearly in different fields that never touch visual art, but it is also valid for this. Substantiated by very few others (including Susan Sontag and Franco Vaccari), it cannot be dismissed as biased: which, if one speaks of music and the other of poetry?

G. de Chirico, 1913, and Pontormo in S. Felicita, Firenze,1526/27

So let’s keep in mind what JB and GG say about their fields, but let’s ask ourselves why there should be a different discourse in that of visual art. If we give the etymological meaning to semantics and not that of the expression of its content, every interpretation, as Sontag (2) states, is a usurpation, a grand deception. Art cannot exhibit any semantic content separate from its form, because it is exactly this that conveys it. The ambiguity linked to the meaning does not interest us, but the mystery of form does (3). If a plethora of exegetes have strived, with good results for their profit, to give an explanation to the convoluted arguments of the “Frenchman”, this does not justify forgetting that the visual language possesses an autonomy of signs that do not preclude the past and are in search of a future that has nothing to do with the lingua franca, even that of the most distinguished critics, one that does not suffer from a translation. Even mine right now: I don’t pretend to do poetry.

G.B. Tiepolo,Venezia,1757 and Gordon Matta, Paris, 1975

Mine is an effort of collation of arguments produced in the lingua franca by two true artists: each of their own words, carefully chosen by me, can be applied to the green of a Poet’s dream as to the Conical hole of Gordon Matta-Clark or Tiepolo, to the pink of Santa Felicita (or to the Hand that indicates it; who? the Pontormo or Giovanni Anselmo?) as to the black of the Rothko Chapel, to the unbalanced Spiral space of Serra as to the agitation of Erasmus of Narni (who is able to curb it in its stillness?). There are no borders in art, nothing sets and often the classics are revived.

Gordon Matta, NY, 1974 and Federico De Leonardis, Peccioli (PI),1990

Here is the series of promised quotes. I’ll start with Gould. After pointing out Bach’s indifference if not unwillingness to write for a given keyboard instrument, Gould uses terms such as smug, silken, legato spinning resource for his own Steinway. This says a lot about the attention to the characteristics of one’s own expressive language:

Giovanni Anselmo, Pointing hand

Bach’s compositional method, of course, was distinguished by his disinclination to compose at any specific keyboard instrument. And it is indeed extremely doubtful that his sense of contemporaneity would have appreciably altered had his catalogue of household instruments been supplemented by the very latest of Mr. Steinway’s “accelerated action” claviers. It is at the same time very much to the credit of the modern keyboard instrument that the potential of its sonority—that smug, silken, legato-spinning resource can be curtailed as well as exploited, used as well as abused.

I suspect I may have unwittingly engaged in a dangerous game, ascribing to musical composition attributes which reflect only the analytical approach of the performer. This is an especially vulnerable practice in the music of Bach, which concedes neither tempo nor dynamic intention, and I caution myself to restrain the enthusiasm of an interpretative conviction from identifying itself with the unalterable absolute of the composer’s will. Besides, as Bernard Shaw so aptly remarked, parsing is not the business of criticism.

As for the reasons for his abandonment of concert halls for recording ones:

Well, you see, Bruno, I don’t really enjoy playing any concertos very much. What bothers me most is the competitive, comparative ambience in which the concerto operates. I happen to believe that competition rather than money is the root of all evil, and in the concerto we have a perfect musical analogy of the competitive spirit. Obviously, I’d exclude the concerto grosso from what l’ve just said.

Marliave’s mention of “the intimate and contemplative appeal to the ear“ illustrates an approach to these works based upon philosophical conjecture rather than musical analysis. Beethoven, according to this hypothesis, has spiritually soared beyond the earth’s orbit and, being delivered of earthly dimension, reveals to us a vision of paradisiacal enchantment. A more recent and more alarming view shows Beethoven not as an indomitable spirit which has overleapt the world but as a man bowed and broken by the tyrannous constraint of life on earth, yet meeting all tribulation with a noble resignation to the inevitable. Thus Beethoven, mystic visionary, becomes Beethoven, realist, and these last works are shown as calcified, impersonal constructions of a soul impervious to the desires and torments of existence. The giddy heights to which these absurdities can wing have been realized by several contemporary novelists, notable offenders being Thomas Mann and Aldous Huxley.

If you are particularly fond of the last works of Strauss, as I am, it is essential to acquire a more flexible system of values than that which insists upon telling us that novelty equals progress equals great art. I do not believe that because a man like Richard Strauss was hopelessly old-fashioned in the professional verdict, he was, therefore, necessarily a lesser figure than a man like Schoenberg who stood for most of his life in the forefront of the avant-garde. If one adopts that system of values, it brings about the inevitable embarrassment of having to reject, among others, Johann Sebastian Bach as also being hopelessly old-fashioned.

His opinion on the relationship between the tastes of the time and the eternity of language see the following fragments:

The generation, or rather the generations, that have grown up since the early years of this century have considered the most serious of Strauss’s errors to be his failure to share actively in the technical advances of his time. They hold that having once evolved a uniquely identifiable means of expression, and having expressed himself within it at first with all the joys of high adventure, he had thereafter, from the technical point of view, appeared to remain stationary—simply saying again and again that which in the energetic clays of his youth he had said with so much greater strength and clarity. For these critics it is inconceivable that a man of such gifts would not wish to participate in the expansion of the musical language, that a man who had the good fortune to be writing masterpieces in the days of Brahms and Bruckner and the luck to live beyond Webern into the age of Boulez and Stockhausen should not want to search out his own place in the great adventure of musical evolution. What must one do to convince such folk that art is not technology, that the difference between a Richard Strauss and a Karlheinz Stockhausen is not comparable to the difference between a humble office adding machine and an IBM computer?

The great thing about the music of Richard Strauss is that it presents and substantiates an argument which transcends all the dogmatisms of art—all questions of style and taste and idiom—all the frivolous, effete preoccupations of the chronologist. It presents to us an example of the man who makes richer his own time by not being of it; who speaks for all generations by being of none. It is an ultimate argument of individuality—an argument that man can create his own synthesis of time without being bound by the conformities that time imposes.

But one last examination of this hypothetical piece: let us assume that instead of attributing it to Haydn or to any later composer, the improviser were to insist that it was a long-forgotten and newly discovered work of none other than Antonio Vivaldi, a composer who was by seventy—five years Haydn’s senior. I venture to say that, with that condition in mind, this work would be greeted as one of the true revelations of musical history-a work that would be accepted as proof of the farsightedness of this great master, who managed in this one incredible leap to bridge the years that separate the Italian baroque from the Austrian rococo, and our poor piece would be deemed worthy of the most august programs. In other words, the determination of most of our aesthetic criteria, despite all our proud claims about the integrity of artistic judgment, derives from nothing remotely like an “art-for-art’s-sake” approach. What they really derive from is what we could only call an “art-for-what-its-society-was-once-like” sake.

The deficiencies of this argument arise from the fact that its proponents simply cannot tolerate the idea that the participation in a certain historical movement does not necessarily impose upon the participant the duty to accept the logical consequences of that movement. One of the irresistibly lovable facts about most human beings is that they are very seldom willing to accept the consequences of their own thinking. The fact that Strauss deserts the general movement of German expressionism (presumably, in Rosenfeld‘s terms, the embodiment of “Nietzsche‘s modernism”) should not be more disturbing than the fact that the unquestioned innovator Arnold Schoenberg found it extremely difficult in his later years to fulfill the rhythmic extenuations of his own motivic theories. The fact is that above and beyond the questions of age and endurance, art is not created by rational animals and in the long run is better for not being so created.

It would be most surprising if the techniques of sound preservation, in addition to influencing the way in which music is composed and performed (which is already taking place), do not also determine the manner in which we respond to it. And there is little doubt that the inherent qualities of illusion in the art of recording those features that make it a representation not so much of the known exterior world as of the idealized interior world-will eventually undermine that whole area of prejudice that has concerned itself

with finding chronological justifications for artistic endeavors and which in the post-Renaissance world has so determinedly argued the case of a chronological originality that it has quite lost touch with the larger purposes of creativity.

Whatever else we would predict about the electronic age, all the symptoms suggest a return to some degree of mythic anonymity within the social-artistic structure. Undoubtedly most of what happens in the future will be concerned with what is being done in the future, but it would also be most surprising if many judgments were not retroactively altered because of the new image of art. If that happens, as I think it must, there will be a number of substantial figures of the past and near past who will undergo major reevaluation and for whom the verdict will no longer rest upon the narrow and unimaginative concepts of the social-chronological parallel.

And so it seems to me a great mistake to read into the fantastic transition of music in our time a total social significance. Undeniably, there do exist correlations between the development of a social stratum and the art which grows up around it, just as the public manner of early baroque music related to some degree to the prosperity of a merchant class in the sixteenth century; but it is terribly dangerous to advance a complicated social argument for a change which is fundamentally a procedural one within an artistic discipline.

Of course, the early propagandists for atonality pointed with a good deal of pride to the fact that the movement toward abstract art began at almost exactly the same time as atonality, and there are certain comfortable parallels between the careers of the painter Kandinsky and the composer Schoenberg.

But l think it is dangerous to pursue the parallel too closely, for the simple reason that music is always abstract, that it has no allegorical connotations except in the highest metaphysical sense, and that it does not pretend and has not, with very few exceptions, pretended to be other than a means of expressing the mysteries of communication in a form which is equally mysterious.

The figure of Schoemberg outlined by the writings of G is emblematic for understanding the linguistic work of a great composer and his responsibility in the detachment of cultured music from popular music:

But the odd thing about it was that with this oversimplified, exaggerated system Schoenberg began to compose again; and not only did he begin to compose: he embarked upon a period of about five years which contains some of the most beautiful, colorful, imaginative, fresh, inspired music which he ever wrote. Out of this concoction of childish mathematics and debatable historical perception came an intensity, a ioie de vivre, which knows no parallel in Schoenberg‘s life. How could this be, then? By what strange alchemy was this man compounded that the sources of his inspiration flowed most freely when stemmed and checked by legislation of the most stifling kind? I suppose part of the answer lies in the fact that Schoenberg was always intrigued by numbers and afraid of numbers and attempting to read his destiny in numbers –and, after all, what greater romance of numbers could there be than to govern one’s creative life by them? I suppose part of it was due to the fact that after fifteen years awash in a sea of dissonance, Schoenberg felt himself to be on firm ground once again. Still another part of it is certainly that all music must have a system, and that particularly in those moments of rebirth such as Schoenberg had led us into, it is much more necessary to adhere to the system, to accept totally its consequences, than at a later, more mature stage of its existence.

I think there can be no doubt that its fundamental effect has been to separate audience and composer. One doesn’t like to admit this, but it is true nonetheless. There are many people around who believe that Schoenberg has been responsible for shattering irreparably the compact between audience and composer, of separating their common bond of reference and creating between them a profound antagonism. Such people claim that the language has not become a valid one for the reason that it has no system of emotional reference that is generally accepted by people today. Certainly concert music of today—

that part of it, at any rate, which owes a great deal to the Schoenbergian influence—plays a very small part in the life of many people. It cannot by any means claim to excite the curiosity that was generally aroused by significant new works fifty or sixty years ego. One must remember that at the turn of the century, any new work by a Richard Strauss or a Gustav Mahler or a Rimsky-Korsakov or a Debussy was a major event not only for the cognoscenti but for a very large lay audience as well.

No matter how little interest there may be in the more significant developments of music in our time, I think that there is little doubt that there are some areas in which the vocabulary of atonality—using this term now in a collective sense—has made quite an unobjectionable contribution to contemporary life. It has done this particularly in media in which music furnishes but a part—operas, to a degree (if you can consider styling Alban Berg’s Wozzeck a “hit”), but most particularly in that curious specialty of the twentieth century known as background music for cinema or television. If you really stop to listen to the music accompanying most of the grade-B horror movies that are coming out of Hollywood these days, or perhaps a TV show on space travel for children, you will be absolutely amazed at the amount of integration which the various idioms of atonality have undergone in these media.

Until here: Glenn Gould. Let us now turn to quoting Brodsky. The following fifteen lines (taken from On Grief and Reason) represent an eloquent summary of his thinking on art in general and poetry in particular, as well as on the meaning of the word “language”. Below I have collected other fragments (also taken from Less Than One) that specify its depth and richness. The only fundamental difference with the visual arts is on the affirmation of the inalienability of the word to the semantic value (unfortunately), but with the specification that this does not apply to the other arts.

For poetic discourse is continuous; it also avoids cliché and repetition. The absence of those things is what speeds up and distinguishes art from life, whose chief stylistic device, if one may say so, is precisely cliché and repetition, since it always starts from scratch. It is no wonder that society today, chancing on this continuing poetic discourse, finds itself at a loss, as if hoarding a runaway train. I have remarked elsewhere that poetry is not a form of entertainment, and in a certain sense not even a form of art, but our anthropological, genetic goal, our linguistic, evolutionary beacon. We seem to sense this as children, when we absorb and remember verses in order to master language. As adults, however, we abandon this pursuit, convinced that we have mastered it. Yet what we’ve mastered is but an idiom, good enough perhaps to outfox an enemy, to sell a product, to get laid, to earn a promotion, but certainly not good enough to cure anguish or cause joy. Until one learns to pack one’s sentences with meanings like a van or to discern and love in the beloved’s features a “pilgrim soul”; until one becomes aware that “No memory of having starred I Atones for later disregard, / Or keeps the end from being hard”—until things like that are in one’s bloodstream, one still belongs among the sublinguals. Who are the majority, if that’s a comfort.

In that, it-life-differs from art, whose worst enemy, as you probably know, is cliché. Small wonder, then, that art, too, fail-s to instruct you as to how to handle boredom. There are few novels about this subject; paintings are still fewer; and as for music, it is largely nonsemantic. On the whole, art treats boredom in a self-defensive, satirical fashion. The only way art can become for you a solace from boredom, from the existential equivalent of cliché, is it you yourselves become artists. Given your number, though, this prospect is as unappetizing as it is unlikely.

Herein lies the ultimate distinction between the beloved and the Muse; the latter doesn’t die. The same goes for the Muse and the poet: when he’s gone, she finds herself another mouthpiece in the next generation. To put it another way, she always hangs around a language and doesn’t seem to mind being mistaken for a plain girl. Amused by this sort of error, she tries to correct it by dictating to her charge now

pages of Paradise, now Thomas Hard}-“s poems of 1912-13; that is, those where the voice of human passion yields to that of linguistic necessity—but apparently to no avail. So let’s leave her with a flute and a wreath wildflowers. This way at least she might escape a biographer.

Of course, when talking about the signs of the word (semanticity) one cannot avoid addressing the theme of the relationship between art and life:

Now, the purpose of evolution is the survival neither of the fittest nor of the defeatist. Were it the former, we would have to settle for Arnold Schwarzenegger; were it the latter, which ethically is a more sound proposition, we’d have to make do with Woody Allen. The purpose of evolution, believe it or not, is beauty, which survives it all and generates truth simply by being a Fusion of the mental and the sensual. As it is always in the eye of the beholder, it can’t he wholly embodied save in words: that’s what ushers in a poem, which is as incurably semantic as it is incurably euphonic.

In “Home Burial“ (Frost’s poem) it results is both. For every Galatea is ultimately a Pygmalion’s self-projection. On the other hand, art doesn’t imitate life but infects it. …

… This is a poem about languages terrifying success, for language, in the final analysis, is alien to the sentiments it articulates. No one is more aware of that than a poet; and if “Home Burial”

is autobiographical, it is so in the first place by revealing Frost’s grasp of the collision between his métier and his emotions. To drive this point home, may I suggest that you compare the actual sentiment you may feel toward an individual in your company and the word “love.” A poet is doomed to resort to words. So is the speaker in “Home Burial.” Hence, their overlapping in this poem; hence, too, its autobiographical reputation. …

… So what was it that he was after in this, his very own poem? He was, I think, after grief and reason, which, while poison to each other, are languages most efficient fuel—or, if you will, poetry’s indelible ink. Frost’s reliance on them here and elsewhere almost gives you the sense that his dipping into this ink pot had to do with the hope of reducing the level of its contents; you detect a sort of vested interest on his part. Yet the more one dips into it, the more it brims with this black essence of existence, and the more one’s mind, like one’s fingers, gets soiled by this liquid. For the more there is of grief, the more there is of reason. As much as one may be tempted to take sides in “Home Burial,” the presence of the narrator here rules this out, for while the characters stand, respectively, for reason and for grief, the narrator stands for their fusion. To put it differently, while the characters’ actual union disintegrates, the story, as it were, marries grief to reason, since the bond of the narrative here supersedes the individual dynamics— well, at least for the reader. Perhaps for the author as well. The poem, in other words, plays fate.

For poetic discourse is continuous; it also avoids cliché and repetition. The absence of those things is what speeds up and distinguishes art from life, whose chief stylistic device, if one may say so, is precisely cliché and repetition, since it always starts from scratch. It is no wonder that society today, chancing on this continuing poetic discourse, finds itself at a loss, as if hoarding a runaway train. I have remarked else-

where that poetry is not a form of entertainment, and in a certain sense not even a form of art, but our anthropological, genetic goal, our linguistic, evolutionary beacon. We seem to sense this as children, when we absorb and remember

For art is something more ancient and universal than any faith with which it enters into matrimony, begets children—but with which it does not die. The judgment of art is a judgment more demanding than the Final Judgment.

Rilke’s Orfeo gives him the cue to clarify his thought on art, which in addition to the close relationship with the meaning of death, arises precisely from the rubbish of life:

This economy is art’s ultimate raison d’être, and all its history is the history of its means of compression and condensation. In poetry, it is language, itself a highly condensed version of reality. In short, a poem generates rather than reflects.

For why should we empathize with him? Less highborn and less gifted than he is. we never will be exempt from the law of nature. With us, the journey to Hades is a one-way trip. What can we possibly learn from his story? That a lyre takes one farther than a plow or a hammer and anvil? That we should emulate geniuses and heroes? That perhaps audacity is what does it? For what if not sheer audacity was it that made him undertake this pilgrimage?

A man of my occupation seldom claims a systematic mode of thinking; at worst, he claims to have a system—but even that, in his case, is a borrowing from a milieu, from a social order, or from the pursuit of philosophy at a tender age. Nothing convinces an artist more of the arbitrariness of the means to which he resorts to attain a goal—however permanent it may be—than the creative process itself, the process of composition. Verse really does, in Akhmatova’s words, grow from rubbish; the roots of prose are no more honorable. …

… Art, generally speaking, always comes into being as a result of an action directed outward, sideways, toward the attainment (comprehension) of an object having no immediate relationship to art. It is a means of conveyance, a landscape flashing in a window—rather than the conveyance’s destination. “If you only knew,” said Akhmatova, “what rubbish verse grows from . . .” The farther away the purpose of movement, the more probable the art; and, theoretically, death (anyone’s, and a great poet’s in particular, for what can be more removed from everyday reality than a great poet or great poetry?) turns into a sort of guarantee of art.

The hierarchy between ethics and aesthetics further clarifies his thinking on the relationship between art and life. This applies to all the arts, as the discourse about what art language means also always applies to all:

On the whole, every new aesthetic reality makes man’s ethical reality more precise. For aesthetics is the mother of ethics. The categories of “good” and “bad” are, first and foremost, aesthetic ones, at least etymologically preceding the categories of “good” and “evil.” If in ethics not “all is permitted,” it is precisely because not “all is permitted” in aesthetics, because the number of colors in the spectrum is limited. The tender babe who cries and rejects the stranger who, on the contrary, reaches out to him, does so instinctively, makes an aesthetic choice, not a moral one.

Unlike life, a work of art never gets taken for granted: it is always viewed against its precursors and predecessors. The ghosts of the great are especially visible in poetry, since their words are less mutable than the concepts they represent.

In such an absence, art grows humble. For all our cerebral progress, we are still greatly subject to relapse into the Romantic (and, hence, Realistic as well) notion that “art imitates life.” If art does anything of this kind, it undertakes to reflect those few elements of existence which transcend “life,” extend it beyond its terminal point—an undertaking which is frequently mistaken for art’s or the artist’s own groping for immortality. In other words, art “imitates” death rather than life; i.e., it imitates that realm of which life supplies no notion: realizing its own brevity, art tries to domesticate the longest possible version of time. After all, what distinguishes art from life is the ability of the former to produce a higher degree of lyricism than is possible within any human interplay. Hence poetry’s affinity with–if not the very invention of—the notion of afterlife.

Poetry after all in itself is a translation; or, to put it another way, poetry is one of the aspects of the psyche rendered in language. It is not so much that poetry is a form of art as that art is a form to which poetry often resorts. Essentially, poetry is the articulation of perception, the translation of that perception into the heritage of language—language is, after all, the best available tool. But for all the value of this tool in ramifying and deepening perceptions-revealing sometimes more than was originally intended, which, in the happiest cases, merges with the perceptions—every more or less experienced poet knows how much is left out or has suffered because of it.

It would be false as well as unnecessary to try to divorce Platonov from his epoch; the language was to do this anyway, if only because epochs are finite. In a sense, one can see this writer as an embodiment of language temporarily occupying a piece of time and reporting from within. The essence of his message is LANGUAGE I5 A MILLENARIAN DEVICE, HISTORY ISN’T”, and coming from him that would be appropriate.

A great writer is one who elongates the perspective of human sensibility, who shows a man at the end of his wits an opening, a pattern to follow.

Burning books, after all, is just a gesture; not publishing them is a falsification of time. But then again, that is precisely the goal of the system: to issue its own version of the future.

Whether one likes it or not, art is a linear process. To prevent itself from recoiling, art has the concept of cliché. Art’s history is that of addition and refinement, of extending the perspective of human sensibility, of enriching, or more often condensing, the means of expression. Every new psychological or aesthetic reality introduced in art becomes instantly old for its next practitioner. An author disregarding this rule, somewhat differently phrased by Hegel, automatically destines his work—no matter what good press it

gets in the marketplace—-to assume the status of pulp.

But to clarify the undemocratic nature of the language, just these sketches taken from some of his most important essays are enough:

Herein, of course, lies arts saving grace. Not being lucrative, it falls victim to demography rather reluctantly.

For if, as we’ve said, repetition is boredom’s mother, demography (which is to play in your lives a far greater role than any discipline you’ve mastered here) is its other parent. This may sound misanthropic to you, but I am more than twice your age, and I have lived to see the population of our globe double. By the time you’re my age, it will have quadrupled, and not exactly in the fashion you expect. For instance, by the year 2000 there is going to be such cultural and ethnic rearrangement as to challenge your notion of your own humanity.