#southern tenant farmers union

Text

April Archives Hashtag Party ~ Archives Snapshot

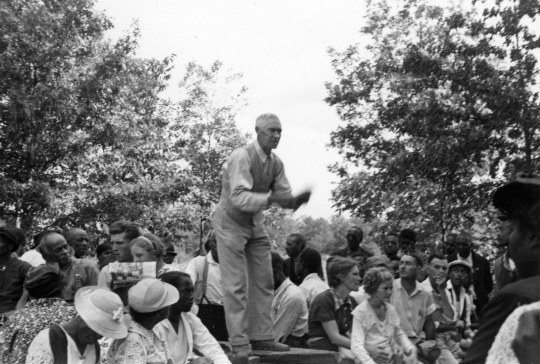

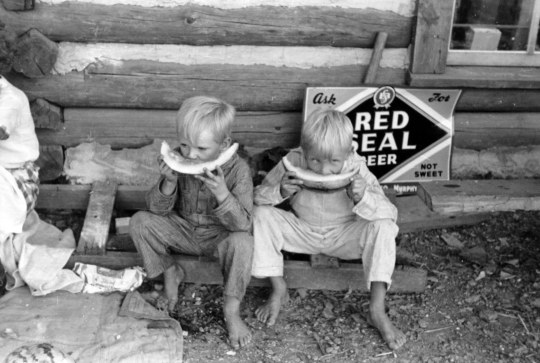

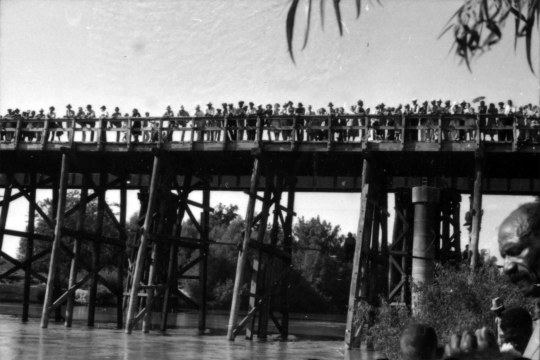

You can observe a lot from one photo... how about ten? Check out these snapshots from a Southern Tenant Farmers Union meeting in Arkansas in 1937, taken by Louise Boyle.

Curious about the Southern Tenant Farmers Union? Check out our digital collection "Louise Boyle. Southern Tenant Farmers Union Photographs, 1937 and 1982" here:

#ArchivesSnapshot#ArchivesHashtagParty#KheelCenter#ILR#CornellUniversity#LaborHistory#LaborArchives#2024#STFU#SouthernTenantFarmersUnion#ArchivesOfTumblr#ILRSchool

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

It’s often said that under capitalism, relations between people appear as relations between things. The butcher, baker, and candlestick maker vanish into the Bed Bath & Beyond. But there’s a countertendency at work within the ruling class, among whom relations between things often appear as relations between people. Mr. Smith seems to have dinner with Mr. Brown, but behind the veil are the bank and newspaper sitting to sup. This is a virtue of the joint-stock model: Huge piles of capital, years of work extracted from labor and subsequently aggregated, meet as men. Capital’s fundamental drive for better-than-average returns means that no operator can be satisfied with a tie, but in order to function the system needs superficial competition on a stone platform of cooperation. In the fascist system competition is external, between nations, its various components conceived as parts of a single body. Individual interest is subordinated to that of the group. That was anathema to [Herbert] Hoover and his fellows, who saw individual interest as the prime mover, society’s engine. Capitalist collectivity emerges in two ways: First, there’s exploitation, wherein capitalists extract bits of value from their employees’ work and gather it up into lumps to reinvest. Second, there’s association, in which investors pledge their gathered lumps to a common cause. Unlike an enveloping fascist state, an associative state comes together like an interoffice softball league, via the ostensibly free and voluntary association of participants.

The stone foundation of capitalist cooperation cracked during the Depression, as near-term self-preservation undermined long-term self-interest. The “Popular Front” alliance between leftists and liberals offered a different model, a democratic state that mediated between capital and labor much the way the associative state mediated among capitalists. The idea had a lot to offer, especially in the face of fascists on the right and communists on the left. The Stanford athletic association treasurer [Hoover] was abandoned, nearly alone in his fidelity. But he grasped something the others didn’t: Financialization and economic democracy can’t blend. If property rights are subject to popular control, then investors will encounter the public as an obstacle, a variable to be managed. For example, banks loaned credit to farms based on existing prices, which were based on the current cost of labor. Improving labor conditions by picket was an attack on property valuation, which thanks to financialization made it an attack on property, full stop. The Roosevelt coalition brought together capital and labor under one roof, but one partner always sought to dominate the other.

Bill Camp was an odd choice for a New Deal bureaucrat, but the banker, cotton planter, and proud son of a Klansman was the right wing of the FDR team, one of the Confederate Democrats who hadn’t left the party yet, except for a single dalliance with the Chief [Hoover] in 1928. He was a link of continuity between Hoover’s agricultural administration and the New Deal version. When the Agricultural Adjustment Act came under legal challenge, Camp was introduced to the left side of the coalition, and he was shocked to discover that his very own lawyer was a communist. Camp knew one when he saw one, and when he realized that Department of Agriculture officials were planning to help the left-wing Southern Tenant Farmers Union get better conditions for cotton workers in the South—Camp’s ancestral stomping ground—he denounced them. Camp called a handful of his conservative politician friends from the cotton belt and they went over the head of the agriculture secretary, Wallace (the new one), straight to President Roosevelt. The next day the president fired the left-wing lawyers, and Agriculture reversed a pro-tenant rule interpretation. But Camp couldn’t forget about his commie lawyer, and when one of Camp’s local congressmen wanted to make a name for himself exposing liberal Reds, Camp fed everything he had on Alger Hiss to Richard Nixon, helping ignite the congressional Red Scare.

Herbert Hoover understood that the social forces Bill Camp and Alger Hiss represented—the plantation owner and the plantation worker—no government could bring into harmony. Capital by its nature dominates labor, and if it fails to accomplish that, it ceases to exist. The rule interpretation Camp objected to bound planters to their existing tenants, which was an untenable attack on their profitability, even though at the time they weren’t profitable at all without the government’s help. The conflict was inherent, and it didn’t take until the end of World War II for the Cold War to start or for liberals to reveal which side they planned to take. After George Creel lost the California gubernatorial nomination to the wacky socialist writer Upton Sinclair, he and FDR knifed the populist author. First they rewrote Sinclair’s platform to moderate it, then they cut a deal with the Republican incumbent, Frank Merriam, anyway—the same Merriam who called the machine guns to the San Francisco waterfront. Merriam trounced Sinclair, who waited patiently for the Roosevelt endorsement that never came. “He didn’t realize at first that communism was the threat,” Camp recalled of Creel, regarding the official’s work; “he became one of the greatest fighters [against communism].” So much for the New Deal.

[…]

Communism, Hoover and his allies saw, was not merely a political party running Russia or an economic philosophy. It was a real movement that threatened to abolish capitalist control over society and thereby destroy capitalism in its entirety. Communists were communists whether they realized it or not, even when they thought they only wanted better wages. It’s easy now to look back and see the Hooverites as victims of a paranoiac fantasy about the world—to see them either as the only ones who really believed the Marxist revolutionary rhetoric or as cynical operators stoking an arbitrary moral panic. But Bert knew the global revolution was real. He saw it in China, narrowly escaped it in Russia, confronted it outside the window in DC, and heard it tear apart his farm in California. They took his mines, and they would kill him and take the rest if he wasn’t vigilant, just like they did to his formerly privileged friends around the world. Still nursing his wounds from defeat but far from vanquished, Herbert Hoover devoted the rest of his life to winning the class war. Palo Alto became his watch tower.

Malcolm Harris, Palo Alto

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The executive branch included an advisory council to the governor that varied in size ranging from ten to thirty members.[21][23] In royal colonies, the Crown appointed a mix of placemen (paid officeholders in the government) and members of the upper class within colonial society. Councilors tended to represent the interests of businessmen, creditors and property owners in general.[24] While lawyers were prominent throughout the thirteen colonies, merchants were important in the northern colonies and planters were more involved in the southern provinces.[citation needed] Members served "at pleasure" rather than for life or fixed terms.[25] When there was an absentee governor or an interval between governors, the council acted as the government.[26]

The governor's council also functioned as the upper house of the colonial legislature. In most colonies, the council could introduce bills, pass resolutions, and consider and act upon petitions. In some colonies, the council acted primarily as a chamber of revision, reviewing and improving legislation. At times, it would argue with the assembly over the amendment of money bills or other legislation.[24]

In addition to being both an executive and legislative body, the council also had judicial authority. It was the final court of appeal within the colony. The council's multifaceted roles exposed it to criticism. Richard Henry Lee criticized Virginia's colonial government for lacking the balance and separation of powers found in the British constitution due to the council's lack of independence from the Crown.[25]

Assembly[edit]

House of Burgesses chamber inside the Capitol building at Colonial Williamsburg

The lower house of a colonial legislature was a representative assembly. These assemblies were called by different names. Virginia had a House of Burgesses, Massachusetts had a House of Deputies, and South Carolina had a Commons House of Assembly.[27][28] While names differed, the assemblies had several features in common. Members were elected annually by the propertied citizens of the towns or counties. Usually they met for a single, short session; but the council or governor could call a special session.[26][page needed]

As in Britain, the right to vote was limited to men with freehold "landed property sufficient to ensure that they were personally independent and had a vested interest in the welfare of their communities".[29] Due to the greater availability of land, the right to vote was more widespread in the colonies where by one estimate around 60 percent of adult white males could vote. In England and Wales, only 17–20 percent of adult males were eligible. Six colonies allowed alternatives to freehold ownership (such as personal property or tax payment) that extended voting rights to owners of urban property and even prosperous farmers who rented their land. Groups excluded from voting included laborers, tenant farmers, unskilled workers and indentured servants. These were considered to lack a "stake in society" and to be vulnerable to corruption.[30]

Tax issues and budget decisions originated in the assembly. Part of the budget went toward the cost of raising and equipping the colonial militia. As the American Revolution drew near, this subject was a point of contention and conflict between the provincial assemblies and their respective governors.[26]

The perennial struggles between the colonial governors and the assemblies are sometimes viewed, in retrospect, as signs of a rising democratic spirit. However, those assemblies generally represented the privileged classes, and they were protecting the colony against unreasonable executive encroachments.[citation needed] Legally, the crown governor's authority was unassailable. In resisting that authority, assemblies resorted to arguments based upon natural rights and the common welfare, giving life to the notion that governments derived, or ought to derive, their authority from the consent of the governed.[31]

Union proposals[edit]

Before the American Revolution, attempts to create a unified government for the thirteen colonies were unsuccessful. Multiple plans for a union were proposed at the Albany Congress in 1754. One of these plans, proposed by Benjamin Franklin, was the Albany Plan.[32]

Demise[edit]

During the American Revolution, the colonial governments ceased to function effectively as royal governors prorogued and dissolved the assemblies. By 1773, committees of correspondence were governing towns and counties, and nearly all the colonies had established provincial congresses, which were legislative assemblies acting outside of royal authority. These were temporary measures, and it was understood that the provincial congresses were not equivalent to proper legislatures.[33]

By May 1775, the Massachusetts Provincial Congress felt that a permanent government was needed. On the advice of the Second Continental Congress, Massachusetts once again operated under the Charter of 1691 but without a governor (the governor's council functioned as the executive branch).[34] In the fall of 1775, the Continental Congress recommended that New Hampshire, South Carolina and Virginia form new governments. New Hampshire adopted a republican constitution on January 5, 1776. South Carolina's constitution was adopted on March 26, and Virginia's constitution was adopted on June 29.[35]

In May 1776, the Continental Congress called for the creation of new governments "where no government sufficient to the exigencies of their affairs have been hitherto established" and "that the exercise of every kind of authority under the ... Crown should be totally suppressed".[36] The Declaration of Independence in July further encouraged the states to form new governments, and most states had adopted new constitutions by the end of 1776. Because of the war, Georgia and New York were unable to complete their constitutions until 1777.

because it was unfair for the black community.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

On this day in 1887, an all-white Louisiana militia massacred 60 striking Black sugarcane workers and 2 strike leaders, destroying Black unionized farm labor in the American South for decades.

Years after US "officially ended" Black slavery with the 13th Amendment, Black sugarcane workers conditions were largely unchanged from slavery. They engaged in back-breaking labor for meager pay while living in old slave cabins.

To improve their situation, Black sugarcane workers reached out to Knights of Labor, who helped them strike for a living wage paid in cash every two weeks. But instead of bargaining, growers fired union members.

Louisiana’s governor called in all-white militias under the command of ex-Confederate General to break the strike. In Thibodaux, a judge authorized local white vigilantes to barricade the town, identifying strikers & demanding passes from any African-American coming or going.

A report of 2 white militia men being attacked sparked the massacre. White vigilantes rode through the neighborhood firing their weapons rounding up and killing striker’s family members. Killings continued on plantations, and bodies were dumped in a landfill.

The assassins went unpunished. There was no federal inquiry, and even the coroner’s inquest refused to point a finger at the perpetrators. Sugar planter Andrew Price was among the attackers that morning. He won a seat in Congress the next year.

Southern Black farm workers would not attempt to unionize again, until the 1930s when the Southern Tenant Farmers Union. But it too was met by a violent racist backlash. The struggle for southern unions continued into the Civil Rights era.

SOURCE: Friendly Neighborhood Comrade @SpiritofLenin

8 notes

·

View notes

Audio

John L. Handcox (1904-1992) was a labor activist, folk singer, and tenant farmer from Brinkley, Arkansas. He was involved in the Southern Tenant Farmers Union, formed in 1934 in Tyronza, Arkansas as the first integrated agricultural union in the country. He directly influenced many well-known activist/musicians like Pete Seeger, who recorded some of his songs (“Roll the Union On,” “Mean Things”). Though he disappeared from the public eye after he was involved with the Southern Tenant Farmers Union, at the union’s anniversary in 1984, he sang two anti-Reagan songs, “Oh No, We Don’t Want Reagan Anymore” and “Let’s Get Reagan Out.”

Let’s Get Reagan Out - John L. Handcox

Clap your hands / Sing and shout / Let’s get Reagan out

Let’s do all we can / To get rid of the war-mongering man / Let’s get reagan out

Oh Stomp your feet / Sing and shout / Let’s get Reagan out

Everything is so bad / He’s the worst president we ever had / Let’s get Reagan out

Oh let’s get Reagan out / Clap Your hands / sing and shout / Let’s get Reagan out

Black and white sleeping in the street / Without shelter or a bite to eat / Let’s get Reagan out

Oh let’s get Reagan out / Clap Your hands / sing and shout / Let’s get Reagan out

He sent the coups / To other lands / To get the poor workers killed

Clap Your hands / sing and shout / Let’s get Reagan out

Let’s get Reagan out / All us folk we must register and vote / On Election Day / Let’s get Reagan out

Oh Let’s get Reagan out / Clap Your hands sing and shout / Let’s get Reagan out / Stomp your feet / Sing and shout / Let’s get Reagan out

#happy death day reagan#i've queued this up for june 5th hope y'all appreciate xx#ronald reagan#john handcox

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Evicted sharecropper reading the Bible. Butler County, Missouri. 1939 In early 1939, A documented bitter roadside protest in southeastern Missouri. During the 1930s the government paid landowners to take thousands of acres out of cultivation, while mechanization also reduced the value of physical labor. In January of 1939, cotton farmers across the Missouri Bootheel evicted thousands of sharecroppers and tenant workers and their families from the land where they had lived and worked for years, or even decades. Organizers from the Southern Tenant Farm Union and local ministers appealed to Christian principles to promote a demonstration by farm laborers. "By mid-January more than a thousand evicted people were camped out along the region’s highways." Most of the protesters were Black, like this elderly worker reading his bible in a roadside tent. White sharecroppers who shared their plight joined the protest, making this an early example of an integrated demonstration for economic justice. (at Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture) https://www.instagram.com/p/CfPF-znpEre/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

1 note

·

View note

Text

June 1938. Memphis, Tennessee. "H.L. Mitchell, Secretary of the Southern Tenant Farmers Union. Union headquarters." Medium-format nitrate negative by Dorothea Lange for the Farm Security Administration.

0 notes

Text

"To: my Friend

Gus Tyler

a member and an officer of one of our finest trade unions - the ILGWU

Who is also the newspaper colomnist I most often agree with and always appreciate.

From "mitch"

august 15th 1979"

#Books#HL Mitchell#Mean Things Happening In This Land#STFU#Southern Tenant Farmers Union#Gus Tyler#ILGWU#International Ladies Garmet Workers Union#Trade Unionism#Unions#Unionism#Socialists#Socialist#Socialism#SP USA#Socialist Party#mine

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Sharecroppers settle at Hill House,1936

Mississippi, United States

Dorothea Lange

crédit photo: Library of Congress

#dorothea lange#1936#fourth of july#delta cooperative farm#christian socialism#cooperative society#mississippi#hill house#children#kids#sharecroppers#southern tenants farmers union#great depression#agricultural worker#agricultural workers#agricultural laborers

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Working-class Black and white people have long understood that we are natural allies, and the owning class has done everything in their power to invent and promote racist ideas to divide us. Bacon’s Rebellion in 1676 occurred when Black and white indentured servants took up arms against the landed gentry of the Virginia House of Burgesses. This interracial militia captured Jamestown and burned it to the ground. Word of the rebellion spread far and wide, and several more uprisings ensued. The planter elite were alarmed and deeply fearful of alliance between their workers, so they enacted laws that permanently enslaved Virginians of African descent and gave poor white indentured servants new rights and status. The white rebels were pardoned and the Black rebels were punished, further cementing the racial divide.

Despite violent attacks by elite forces, poor whites and Blacks continued to organize together. They formed the Southern Tenant Farmers Union, an interracial alliance demanding their fair share of subsidies and profits, and improved working conditions. Harrison George of the Communist Party remarked in 1932, 'The impoverished farmers are on the march. We cannot order them to retreat, even if we desired.'

Our generation must carry on this march. White supremacy erodes our humanity and is our common enemy. The white elite created white supremacy, a 'historically based, institutionally perpetuated system of exploitation and oppression of continents, nations, and peoples of color by white peoples and nations of the European continent for the purpose of establishing, maintaining and defending a system of wealth, power and privilege.' White supremacy infuses all aspects of society including our history, culture, politics, economics, and entire social fabric, producing cumulative and chronic adverse outcomes for people of color. What can be created, can be destroyed. White people need to be active in the dismantling of white supremacy."

-Leah Penniman, Farming While Black: Soul Fire Farm’s Practical Guide to Liberation on the Land

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

“One might ask how a Delta planter, often a pillar of his community and church, subscribing to a chivalric code of personal integrity and honor, could justify such exploitative conduct toward dependents. The answer lies in part in the nature of Delta society. Life in the plantation South moved slowly in ordered patterns, governed by the ever-repeated cycle of the crop and the rhythms of the seasons. Changes came gradually, and to the occasional visitor time itself sometimes seemed suspended in the hot, torpid air. Each plantation county had its recognized first families; its quiet sturdy yeomen (the small white farmers); its quota of poor whites; and its black tenants, croppers, and field hands. Each of these classes had its recognized and acknowledged place in the social order, and all were entwined together and connected in a web of reciprocal duties and obligations. Within the established social hierarchy, landowners took a close interest in their dependents, getting them out of scrapes with the law, extending money and help in times of emergency, and otherwise lending assistance. In fact, it was exactly the centrality of personal relationships which sustained social harmony and the sense of community. When acting within this social matrix, planters and local white elites often did function as protectors of rural blacks who were their dependents, their "people." To them this role seemed as natural and inevitable--or so it was assumed in the Victorian and Edwardian ages--as for a white male to shield and protect his female dependents, his wives and daughters. [...]

However, whenever the black underclasses seriously challenged the economic structures and social hierarchy of the plantation world, the planters and the local white leaders and elites allied with them could quickly cease to be protectors and instead became perpetrators of violence and repression. The late nineteenth-century agrarian revolt provides one striking example. Faced with hard times in Southern agriculture and falling cotton prices and incomes, discontented small white farmers as early as the late 1880s and early 1890s threatened to bolt the elite-dominated state Democratic Party and join radical third-party insurgences such as the Union Labor and Populist parties. When Arkansas Republicans endorsed the Union Labor Party state nominees in 1888 and 1890, the effect was to create a biracial coalition of poor blacks and poor whites. Democratic leaders responded by "playing the race card" in part to distract attention from troublesome economic issues that were beginning to divide the white vote. To hammer home the point that the Democratic Party was the party of white supremacy, Democratic lawmakers began to enact a new series of Jim Crow laws mandating separation of the races. To contain further the agrarian radicals, Democrats engaged in the widespread use of electoral fraud and terror and violence to reduce the agrarians' strength. These methods were quickly followed in 1891 by the adoption of a new state election law that placed the dominant Democratic Party in control of the election machinery in every county in Arkansas and that discouraged illiterates from voting. The following year, a poll-tax requirement for voting was implemented. Together these measures reduced voter participation by one-third within a four-year period and removed all blacks from the state legislature. Similarly, blacks were swept from virtually all county and local offices. The last blacks lost their offices in Phillips County in 1894.”

- “Protectors of Perpetrators? White Leadership in the Elaine Race Riot” (John Williams Grace, Arkansas Review: A Journal of Delta Studies)

#racism#american history#us history#american reconstruction#civil war#acw#american civil war#history#quotes#i like this passage bc i think it sums up a lot of the stuff that i think a lot of white northerners don't rlly get#in terms of how race and economics are so interconnected#which is smth i think abt a lot#and i think it's this lack of understanding that makes so many white ppl unable to understand institutionalized racism

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

hi rgr! history q: do you have any examples of labor and tenant organizing working together that I could go read up on. thank u for all u do in this world of blogs !!!

Yes! I actually would hasten to argue that the categorization of tenant action as separate from labor action probably wasn’t very meaningful to most historical rent strikers, and fundamentally tenant action is a kind of labor action. I feel like you see this most explicitly outside the US though, in the past and today. Italy in the seventies immediately comes to mind. There’s some of this work going on right now in Italy and Spain but I can’t yet give you specifics--if you have language skills or connections there you may be able to do better than I can.

(That tenant actions are always theoretically labor actions can tell you, then, that you’ll find rent strikes in the US the same places you’ll find labor strikes: the late thirties and early forties, the late sixties and early through mid seventies, in particular.)

Most immediate example I can think of is Chicago beginning in 1966--this was a really coalitional movement but it’s one major example I can think of of AFL-CIO involvement. At the same time the UAW was backing rent strikes in Detroit. Politics in each case is complicated of course.

Better example--black southern workers in the thirties engaged in tenant action directly related to labor action. Even though the Southern Tenant Farmers Union is really well known and fairly well studied imo this work doesn’t get as much credit for informing the shape of later tenant activism. Best place to find coverage of this is in the major black papers, namely the Chicago Defender and Pittsburgh Courier. Some good examples are Memphis, Arkansas and Missouri 1936-1940. There was a lot of tenant-landowner conflict over new deal ag policies, especially the AAA, which resulted in mass evictions and mass protest and some federal aid for southern renters.

Just some places to look--also like, probably New York lol, I just don’t know the specifics immediately. More later!

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book Review: James M. McPherson's Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era and the Persistence of the Lost Cause Myth

In terms of influencing how both the public and professional historians perceive and understand the American Civil War, there is no better book on the subject than James McPherson’s masterful work and crowning achievement: Battle Cry for Freedom: The Civil War Era. Published in 1988 by Oxford University Press, this insightful, Pulitzer prize-winning book on the bloodiest four years in America’s history still holds up since it’s release over thirty years later which led it to becoming one of the most commonly used texts for students in an unspeakable amount of classrooms across the United States. The texts extremely prevalent academic use is mainly due to how deeply it dives into the political, cultural, and economic determinants that led to war, its extensive use of quotes with well-supported endnotes, and its ability to come across as impartial when presenting information.

When it comes to purview, this hefty tome of over a thousand pages is extensive in it’s coverage of the American Civil War. Not only does the author focus on the course of the four-year conflict, from the Battle of Fort Sumter to the assassination of President Lincoln, but a significant portion of the book is also devoted to describing and analyzing the political and economic differences between the North and the South that facilitated in the outbreak of the war. For example, the book doesn’t go into detail concerning the initial start of the war when until the eighth chapter, while earlier chapters are dedicated to precursor clashes that further divided Americans who were either pro-slavery or free-soiler, including the question of slavery in the territories, the conflict between Jeffersonian republican ideals and industrial capitalism, the Missouri Compromise, Bleeding Kansas, the Kansas-Nebraska Act, the Fugitive Slave Act, the Dredd Scott v. Sandford case, and John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry.

The author also skillfully weavs well-documented opinions amongst the books narrative, especially those from then-contemporary orators, manufacturers, educators, politicians, generals, common soldiers, journalists, and farmers, the book provides the proper context that led to the tragic American Civil War and how it effected those who lived in both of the North and the South. By citing the experiences of both the lives of Northern and Southern civilians, as well as the major players before and during the war, the author demonstrates how socio-political, economic, and cultural history is heavily intertwined with military history. Typically those who are just getting into history have the habit of over-focusing on wars considering the fact they tend to be flashy and dramatic events that can easily grasp one’s attention, but Battle Cry for Freedom reveals how important the study of cultural developments can be in order to understand how conflicts arise.

Lastly, McPherson chronicles the circumstances surrounding the American Civil War with a significantly neutral tone. The author makes it implicitly clear that he’s refraining from making any form of judgement calls towards any actions or viewpoints made by individuals from either side when discussing the series of events and instead lets the reader decide which perspective is the correct one. However, this devotion to an unbiased overview of the American Civil War does not prevent the book from being an excellent source of information when confronting known myths surrounding the wars origins. The book is an especially useful tool when it comes to debunking a specific pro-Southern interpretation of history that has considerably infected they way we view the Civil War known as “the Lost Cause of the Confederacy” or “the Lost Cause of the South.”

For those who are unfamiliar with the concept, the Lost Cause myth is an enduring pseudo-historical interpretation of American history that takes a pro-Southern view of the war. This literary and cultural phenomenon originated from the written works of former Confederate generals, politicians, and lecturers during the Reconstruction years as a means for southerners to psychologically cope after their defeat in war at the hands of the Union army and to perpetuate racist and white supremacist policies, such as Jim Crow Laws, in the South. The primary tenant of the Lost Cause myth, which gained considerable prominence during WWI, was that, rather than fighting for the preservation and extension of slavery, Confederate soldiers are instead described as competent and noble defenders of “states’ rights” against “Northern Yankee aggression.” For anyone who is familiar with the Cornerstone Speech and the Fugitive Slave Act, this attempt at justifying the Southern cause is ultimately a foolish notion due to the fact that it lacks any scholarly merit.

Adherents to the Lost Cause myth also portray Confederate generals, especially Robert E. Lee, as representing the epitome of Southern chivalry and military competency who were only defeated by the Union due to the latter’s superior manpower and manufacturing capabilities. As a result of such pervasive rhetoric that overglorified those who fought for the Confederacy, measures to memorialize the rebel military commanders are war dead by constructing statues and monuments in dedication to Confederate soldiers increased dramatically in the late 1800s and early 1900s during formation of the Jim Crow-era South. This romanticization of the antebellum South made manifest through the construction of public monuments firmly tied this negationist interpretation of history to the enforcement of white supremacist policies that disenfranchised African Americans living in the South.

This is why there is no better time than now to reacquaint oneself with the complex and tragic history of the American Civil War and it’s lasting effect on our culture. With the recent controversy surrounding the protests against Confederate memorials and monuments that still stand all across the country and the fact that our very own president defends their existence as supposed symbols of our heritage, it’s important now more than ever to counter any myths and misconceptions about this horrifying conflict whose main cause undoubtedly involved the issue of slavery. Battle Cry for Freedom, therefore, is an excellent tool in this endeavor of combating Neo-Confederate propaganda and I can’t recommend it enough to anyone who is interested in learning about the history of the Civil War.

#american civil war#slavery#south#union#confederacy#lincoln#lost cause#blm#blacklivesmatter#jim crow#gettysburg#white supremacy#frederick douglass#emancipation

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

In the spring of 1919, a group of Phillips County African-American sharecroppers and tenant farmers, many of them veterans who had recently returned from service overseas in World War I, decided to challenge this system by joining a union called the Progressive Farmers and Household Union of America (PFHUA), which had been founded the year before by army veteran Robert Lee Hill, a black tenant farmer in Winchester, Arkansas. The union’s goal was “to advance the interest of the Negro, morally and intellectually,” and its constitution ended with a proclamation: “WE BATTLE FOR THE RIGHTS OF OUR RACE; IN UNION IS STRENGTH.”

The PFHUA’s challenge to both white supremacy and the economic domination of the planter class took place amid the combustible atmosphere of the Red Scare—the post-World War I panic provoked by the Bolshevik Revolution, anarchist bombings, a huge wave of labor unrest including a general strike in Seattle, and by race riots that shook more than two dozen cities during the Red Summer. Elaine’s white population was already on edge at hearing reports that blacks were daring to organize, and further distressed by the arrival at Phillips County post offices of The Messenger, a militant black newspaper based in New York. An editorial in the paper urged sharecroppers to revolt: “Strike! Southern white capitalists know the Negro can bring down the white bourbon South to its knees by one strike at the source of production.”

#white supremacy#black history#african american history#1919#20th century#centennial#elaine arkansas#cw racial violence#long read#us history#american history

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

went to the the southern tenant farmers union museum yesterday…… arkansas history classes could be SO good

#u know. the 1st integrated ag union & started by socialists in rural e arkansas in the 30s#big too!!!#ok . oh well. only had lessons on different newspaper owners instead. w/e#(johnny cash home in dyess was interesting too)#if ur ever around memphis/e AR u should go#katie speaks

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

stfu? why are we talking about the southern tenant farmers union all of a sudden?

1 note

·

View note