#space shuttle atlantis

Text

STS-45 Atlantis Launch

"With its twin solid rocket boosters and three main engines churning at seven million pounds of thrust, the Space Shuttle Atlantis thunders skyward from Launch Pad 39A. Liftoff of Mission STS-45 occurred at 8:13:40 a.m. EST, March 24, 1992. On board for the 46th Shuttle flight are a crew of seven and the Atmospheric Laboratory for Applications and Science-1 (ATLAS-1). The launch is the second in 1992 for the Shuttle program and Atlantis' 11th flight."

Date: March 24, 1992

NASA ID: 92PC-0644

#STS-45#Space Shuttle#Space Shuttle Atlantis#Atlantis#OV-104#Orbiter#NASA#Space Shuttle Program#launch#LC-39A#Kennedy Space Center#Florida#March#1992#my post

176 notes

·

View notes

Text

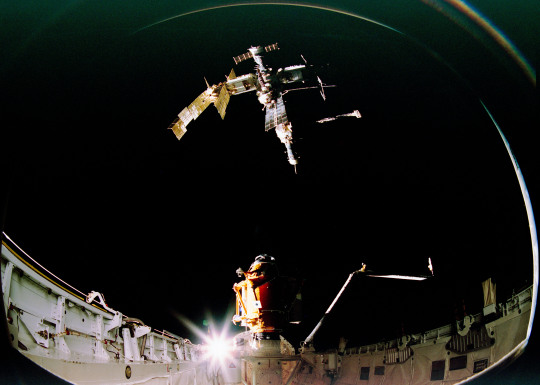

Shuttle-Mir Approach (December 28, 1995)

#space shuttle#space station#space shuttle atlantis#mir space station#russia#nasa#krakenmare#astronomy#astrophotography#outer space#space#thank you nasa

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

The crew of the Space Shuttle Atlantis as seen from the Mir space station, November, 1995.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Space Shuttle Atlantis lifts off from the Kennedy Space Center, Florida, 2008. (Hi-Res).

#liftoff#rocket#rockets#shuttle#shuttles#space#space shuttle#space shuttles#space shuttle atlantis#kennedy space center#clouds#sky#florida#america#u.s.a.#2008#2000s

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Yeet to Mir, Quantum Leap S01E02 “Atlantis”

#Quantum Leap#Quantum Leap 2022#Atlantis#Space Shuttle#Space Shuttle Atlantis#Mir#space station#scifiedit#tvedit#qledit#GIF#my gifs#Danny watches Quantum Leap 2022

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

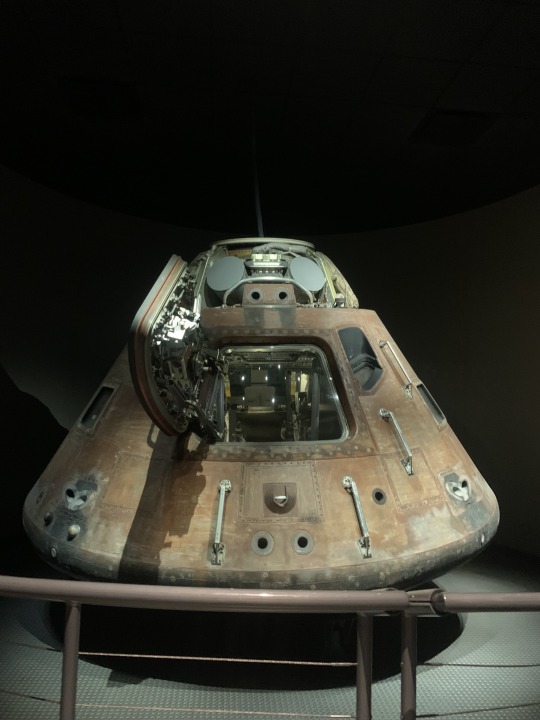

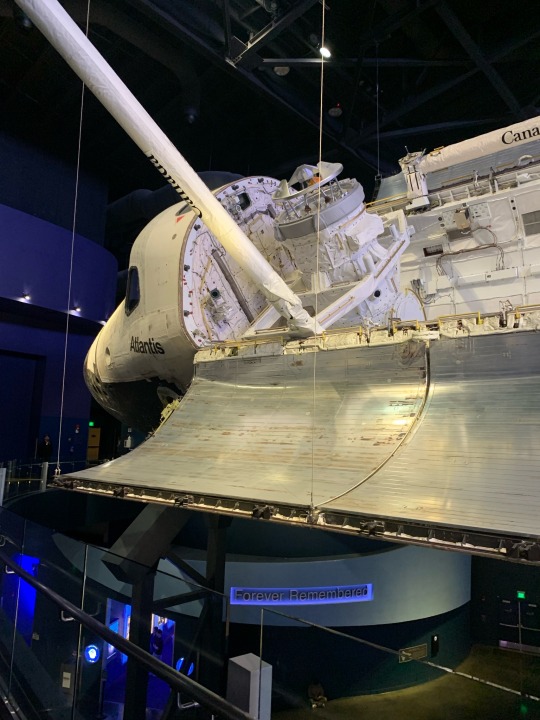

February 14, 2023

Kennedy Space Center Visitor Complex, Florida

#photography#kennedy space center#florida#cape canaveral#space#space travel#apollo space program#rocket ship#space shuttle#space shuttle atlantis#lunar roving vehicle

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rainy Kennedy Space Center day with @kinkocrossing and @stishovite

Finally got to wear my vintage black watch tartan wool capelet 💙

#kennedy space center#vintage#vintagewear#capelet#rocket garden#space shuttle#space shuttle atlantis

0 notes

Link

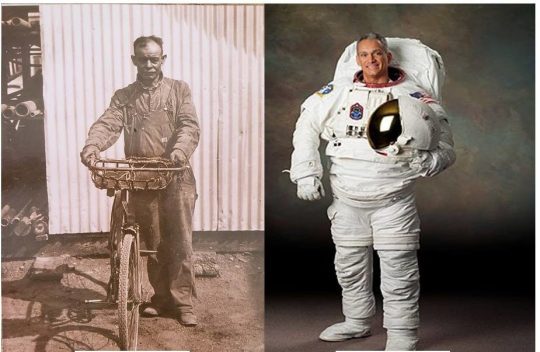

Astronaut Danny Olivas, who served NASA from 1998 to 2010 and spent 27 days and 17 hours in space

John Daniel “Danny” Olivas became the first U.S.-born man of Mexican descent to travel to space. (Rodolfo Neri Vela, who was part of a NASA Space Shuttle mission in 1985, had been born in Mexico; Ellen Ochoa, whose first spaceflight took place in 1993, was the first U.S.-born person of Mexican descent to make it into outer space.)

Olivas was born in North Hollywood, California, in 1965. He received a B.S. in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at El Paso in 1989, an M.S. in mechanical engineering from the University of Houston in 1993, and a Ph.D. in mechanical engineering and materials science from Rice University in 1996.

Olivas developed a strong enthusiasm for space travel early on in life. In 1998, he was accepted into NASA’s astronaut candidate program. Prior to flying into space, Olivas was an aquanaut for NEEMO (NASA Extreme Environment Mission Operations) missions in the Aquarius underwater laboratory.

In 2007, Olivas made his inaugural space flight as part of the seven-person crew of the STS-117 mission on board Space Shuttle Atlantis. Olivas made two spacewalks during the mission. Olivas’ other spaceflight occurred in 2009, when he was part of the seven-person crew of the STS-128 mission on board Space Shuttle Discovery. During this mission, Olivas made a total of three spacewalks. The cumulative time he logged for spacewalks during both missions was 34 hours and 28 minutes.

Astronaut John “Danny” Olivas spacewalking during Space Shuttle Discovery’s STS-128 mission

On June 9, 2007, the day after the Space Shuttle Atlantis mission STS-117 launched into Earth’s orbit, its crew made an alarming discovery. Using the shuttle’s robotic arm, astronauts conducted a visual inspection of the vehicle’s exterior and found a small, triangular-shaped tear in its thermal protection system. Though NASA publicly downplayed it at the time, everyone involved with the mission knew just how critical the problem could prove to be.

When the Atlantis crew opened up the shuttle’s payload bay doors, the problem they discovered was something NASA had not contemplated. The damage was not to the tiles of the main body’s heat shield, but rather to a blanket-like material that covered the tail of the vehicle, near the giant rocket engines known as the orbital maneuvering system, used to move the shuttle around in space.

The hole in the fabric was believed to be mere inches. But the pressure on the area during reentry would be immense. In orbit, the shuttle traveled at 25 times the speed of sound, or 17,500 miles per hour. In order to slow down enough to land, during reentry, the shuttle would use the cocoon of gases that would surround the spaceship when it entered the Earth’s atmosphere to help slow its descent. Those gases, however, reached temperatures of 3,000 Fahrenheit. It was exactly this pressure that had led to fatal disintegration of Space Shuttle Columbia, which had occurred four years earlier.

Olivas had voluntarily removed himself from flight status for two years in the wake of Columbia and joined the team of engineers in order to better understand what had occurred and prevent it from happening again.

“We lost the vehicle, but most importantly, we lost seven astronauts,” Olivas said. “For me, personally, I lost seven colleagues, and I lost seven friends.”

Columbia’s problem had likewise been damaged thermal protection that resulted when a piece of foam insulation broke off from the shuttle’s launch rocket and struck its left wing, punching a hole in its heat shield. The astronauts couldn’t do anything about the problem. They had no means of repairing it.

Astronaut Danny Olivas repairing Space Shuttle Atlantis’ thermal protection system during STS-117 mission

The Atlantis crew sent photos of the torn fabric to mission control in Houston, and went about their mission, which was to deliver and install parts to complete the International Space Station (ISS) energy systems, including its solar arrays.

Olivas knew more about the thermal protection system than anyone else on board. He also knew the engineers and mission crew on the ground very well, having spent two years working alongside them examining what had happened to the Columbia. He trusted they’d find a solution.

It was considered an Extravehicular Activity (EVA) issue, NASA’s terminology for space walking, since the solution would clearly need to come by sending an astronaut outside the vehicle to repair the tear. The EVA toolkit was extensive, but nothing aboard seemed quite right.

“They say when you have a hammer in your hand, that all the world’s problems to you look like a nail, and that’s what you are going to use to solve your problems,” Olivas said during a TEDx talk in 2019. “You’ll notice how human an endeavor spaceflight is by looking closely to the tools used to do a spacewalk, [which] are actually very similar to the tools you’d probably find in your toolbox at home. You’ll see vice grips, pliers, scissors, spatulas. That’s because spaceflight is not that different. The environment is different, but it’s still a human endeavor.”

The astronaut NASA chose to make the spacewalk and attempt the repair was Olivas.

For Olivas, it felt like a prophecy fulfilled. He is Mexican-American and comes from a long line of men who had made their living with their hands. His great-grandfather, Valente Olivas, had crossed into Texas from Chihuahua in 1894. His father, Juan, was a machinist with a knack for fixing things, which his son inherited.

When Olivas was growing up, it was hard for him to imagine himself actually pursuing his dream, which from the age of 7 had been to be an astronaut.

“Because I never thought of myself as having ‘the right stuff’,” Olivas said in an interview. “From the professors I interfaced with, to the astronauts I saw on television, none of them ever looked like me. And so I never thought of myself as being an astronaut.”

Early in the morning of the eighth day of STS-117’s mission, on June 15, Olivas switched his spacesuit to internal power, the airlock aboard the shuttle opened, and he walked into space. He anchored himself at the end of Atlantis’ robot arm and went to work on the tear outside the Orbital Maneuvering System.

The helmet visor of astronaut John “Danny” Olivas, STS-117 mission specialist, serves as an easel of sorts as it reflects a pictorial account of a portion of a very busy session of extravehicular activity (EVA) on June 15 2007. Olivas stapled and pinned down a piece of thermal blanket on one of Atlantis’ orbital maneuvering system pods (reflected in his visor). The repair took three hours of a nearly eight hour spacewalk. The 4-by-6-inch corner of the blanket peeled up during the shuttle’s launch

“The actual hole in the OMS structure was about 4″ x 6″ but the damage extended along the length of the leading edge of the blanket for about two feet,” Olivas said. “The repair was supposed to only take 1.5 hours to complete but actually took a little over three hours once I was able to determine the extent of the damage.”

He and a fellow astronaut spent 7 hours and 58 minutes spacewalking, also folding up a solar array on the Space Station. Olivas successfully repaired the thermal blanket, as evidenced by the Atlantis’ safe return to Earth on June 22, 13 days and 20 hours after launching into space.

Olivas thought of his father throughout his mission. Juan Olivas, who had worked on rocket parts for Gamma Precision Products in North Hollywood prior to returning to El Paso when Danny was four years old, planted the seed in his son’s imagination.

“For Christmas one year, he bought me a telescope,” Olivas said. “I remember as a kid I would go up with him on top of the roof, and we’d look through the telescope and look at the moon. “

When Olivas was 7, he remembers his father telling him and his brother and sister about his own little part in the space program.

“I thought, ‘Wow, all that stuff I just saw in that museum, my dad was a part of that!’” Olivas said. “‘That’s what I want to do: I want to be a part of that, whatever that is. I don’t know how I’m going to do it, but that’s what I want to do.”

Olivas would eventually take part in another Space Shuttle mission, STS-128, in 2009. In total, he would spend 27 days and 17 hours in space, including 35 hours spacewalking.

American Dreams

Early in the afternoon of Aug. 3, Marie Schwarzkopf-Olivas watched in horror as the images poured across the television from El Paso. A white supremacist had shot and killed 22 people at the Walmart she and her family frequented, and her husband Danny still went to every year when he returned for hunting trips.

One of their friends was a confirmed victim of the attack.

“This is our family,” Danny Olivas said. “It’s very visceral. It’s real. Because it’s something we never, ever thought could happen in El Paso. It could have been us.”

“That’s our neighborhood. It’s right by Burges High School. We both went to Cielo Vista Mall, which was the mall where all the chaos was breaking out. Every time we go to El Paso, we go to that Walmart. It’s the same Walmart that my mom buys her bread or milk at. So this really hit home for us.”

The Olivas family had been moved to action more than a year earlier when children began being detained and separated from their families at detention centers along the United States-Mexico border. Olivas, as a former astronaut, had always stayed out of anything that could be perceived as the political fray. But well before the shooting, El Paso came under fire from President Trump and his supporters. Trump, in his State of the Union Address, referred to El Paso as “one of our nation’s most dangerous cities” as he argued for a border wall to stop what he described as an invasion.

Danny and Marie Olivas didn’t recognize El Paso in the president’s descriptions. The couple experienced an idyllic childhood in the border town, one in which the actual border was not the least bit frightening but something quite the opposite. Both regularly crossed the Sante Fe bridge into Juarez, Mexico.

“When we were growing up, and still today, people from Juarez…they were our neighbors,” Marie Olivas said. “That’s just where they lived. The house they lived in just happened to be on the other side of the border. We went to school with them, they were our friends, we went to parties with them. We crossed the border just as if it was any bridge. They were our neighbors, and are still our neighbors today.”

Even before marriage, the couple together hatched a plan: Danny would become an astronaut. He applied with NASA for the first time in 1988, and regularly thereafter. They moved to Houston for graduate school; Danny stayed in school and obtained his Ph.D. He took a job in a small city south of Houston after college. That’s when he first realized how different things could be from El Paso, where race divisions are all but nonexistent.

One day, Olivas did some calculations for a project he had been assigned and took the completed work to a journeyman. The man asked if another engineer, Olivas’ peer, had approved the numbers.

“No,” Olivas said, not quite comprehending. “This is my project. I’m doing this, and here are the numbers you need to use.”

He sent him to another engineer, who was white, to double-check the numbers.

“No,” Olivas said. “You are going to take these for what they are, and if you have a problem with it, talk to my boss.”

He would encounter racism throughout his career, even after he was finally selected by NASA, in 1998, as an astronaut.

“As a U.S. astronaut, I have always tried to steer clear of politics…I’ve tried to be even-keeled, as opposed to giving my own personal opinion,” Olivas said. “But this idea of race has been an underlying theme that has been present my entire career, something that I have had to deal with.”

During his first month within the astronaut corps, he was assigned an office with a classmate, who was white. One morning, his fellow astronaut turned to him and said, matter-of-factly, that Olivas was chosen as an astronaut because of the color of his skin, not his accomplishments.

“And yet when I took a look at my credentials, my credentials were equal to or better than anyone else that got selected,” Olivas said.

“I think it’s important that we all remain engaged and not look the other way when we see what we see. We can’t remain quiet. Otherwise, we become complacent, and we become complicit with what’s going on, because we are failing to stand up and do something about it. And while maybe all that we are doing right now is sharing our voice and sharing our story, and just trying to get the word out to those who are willing to listen, that is better than staying quiet” said Olivas.

At the border

In early April 2018, Attorney General Jeff Sessions announced that the Department of Justice would institute a policy of “zero-tolerance” for undocumented immigrants. Formerly, people who were caught crossing the border for the first time were typically charged with misdemeanors and then released. Under the zero-tolerance policy, all undocumented immigrants would be fully prosecuted by the DOJ. What this meant, in practice, was that in order for prosecution to occur, Customs and Border Patrol would need to separate children from their parents.

As an internal White House memo later obtained by the Washington Post would reveal, this separation of families was not simply a byproduct of increased prosecution. Family separation was a policy unto itself, designed as a deterrent to prevent border crossings.

As soon as family separation began occurring, photos of small children wailing as they were taken from their parents appeared in news outlets across the nation.

Marie and Danny Olivas were at the border within days.

According to a government report, in the wake of the zero-tolerance policy, 2,737 children were separated from their parents, some for days, some for weeks or months, and a few indefinitely. Six of those children have died while in the custody of Customs and Border Patrol.

Danny and Marie Olivas have five children. Danny decided they couldn’t just stand by and watch. Their original intention was not political — they simply wanted to visit the children held in the detention centers in El Paso, and in Tornillo, where a tent city housing immigrant children had been constructed. Danny had written a children’s book, in both Spanish and English, about the Space Shuttle program, called “Endeavor’s Long Journey,” and hoped to give the books to the kids at the detention centers.

“We thought, ‘Well, gosh, we’ve got these books…But the woman there, she told us they had their own curriculum,” Marie said. “Which was a lie.”

The Olivas’ were denied entry to any of the facilities. Turned away, they began documenting what they saw — kids waving at them through the camp fence; a legal proceeding in which two unaccompanied little boys, ages 3 and 5, were expected to represent themselves before a judge; a group of American and Mexican kids meeting at a border barrier, taking turns petting a puppy through the slats in the fence. On Father’s Day, they decided to return again, later in the month.

“Father’s Day was particularly hard for Danny that year in 2019 because it was unbearable to realize how many immigrant fathers were not only without their children but their children’s whereabouts or the prospect of when and if they would ever see their children, unknown,” Marie wrote on her blog. “Stories of politicians not gaining access to the Tornillo Children’s Facility started pouring in and we began to panic …Anyone who knows Danny knows he has a special gift for inspiring children. After all, Danny has been speaking to large groups of children, including El Paso children, for 20 years. Danny is not a politician and up until then only politicians and reporters had tried to gain access to the facility. As Danny’s partner, I was convinced the facility would recognize that Danny was not asking to gain entry for a political stand but rather to bring a message of hope. I believed rather naively the facility guards would welcome a Spanish speaking astronaut bringing a message of hope to their charges.”

Olivas decided to use his status as a U.S. astronaut to help kids obtain legal representation, launching “Between Land and Sea — Borders from Space,” a campaign in support of Diocesan Migrant & Refugee Services, Inc (DMRS), the largest provider of free and low cost immigration legal services in West Texas and New Mexico.

He was also growing more outraged by what he was witnessing.

“At the time there was this fear-mongering about this ‘invasion,’ that they were just pouring over the borders,” Olivas said. “We went down there also to show that is a lie. It’s not about it being inaccurate. It’s a lie; it’s a fabrication. It did not exist. I went with my son, about a month later in 2019, and we drove along the southern border of New Mexico, which parallels the border of Mexico and the United States, where all there are these white marble pylon markers which denote the U.S. and Mexican border. And there is no fence out there, there’s nothing — because there is no invasion.”

They also witnessed what appeared to be illegal actions by the border guards, as people seeking asylum were not even allowed to apply. Under federal law and international treaties, people fleeing persecution in their home country may seek to live in safety in the United States. Asylum seekers formerly had a process to follow, one in which they were allowed in the U.S., pending approval or denial of their application.

“They are all trying to come here legally,” Marie said. “But there are armed guards, and we documented that those armed guards are saying, ‘No, you can’t come over,’ feet away from the port of entry, where they can claim asylum. They weren’t even allowing them to enter; there was no opportunity given to them. Or they were telling them stories, like, ‘Oh, you need to go that other port of entry, which is 50 miles — you have to walk through the desert, to get to that point of entry.’ This is when they were actually walking through the desert and people were like, ‘Why would you take your kid to the desert? What a ridiculous parent you are; you deserve to get your kid taken away.’ But they were telling them, ‘No, you need to get to that port of entry, and they would walk through miles of just treacherous desert and as soon as they entered that point of entry, guards would arrest them and say, ‘You just entered illegally.’ And they would take their children away.”

Deportation isn’t something unique to the then Trump administration and its management of the border. What was new was the destruction of the asylum-seeking process and the separation and jailing of children.

The El Paso/Juarez area, as seen from the Space Shuttle Atlantis. Photo by Danny Olivas

On the second to last day of the STS-117 Space Shuttle Atlantis mission, Danny Olivas found himself with some unexpected time on his hands. The astronauts had been scheduled to come home that day, but due to weather, they’d been waved off. This meant they had a half day with which to do absolutely nothing, an extreme rarity in spaceflight, where astronauts’ days are scheduled down to five-minute increments.

Olivas and another co worker decided to look at the stars. They made their way to the flight deck of the Atlantis, covered up all the hatches to make it as dark as possible inside, and looked out at the night sky.

“I’m a stargazer,” Olivas said. “I love looking at the stars…to just put things into context, on the clearest night here on Earth, in the darkest area, you will see the Milky Way, you can see all sorts of stars, and beautiful celestial bodies. In space, the stars are not brighter, but there are orders of magnitude more because you don’t have to look through the atmosphere.”

As Olivas looked out the rear window, he noticed, off the right wing of the Space Shuttle, what appeared to be two clouds in space.

He grabbed a pair of binoculars to look more closely at what he was observing, and then realized — he was looking at the Magellanic Clouds, which are actually our neighboring galaxies, formed at the same time as the Milky Way 14 billion years ago. Unlike our galaxy, these are not spiral in shape, but irregular.

“When I looked through the binoculars, I remember distinctly when I looked in those little tiny eyepieces looking deep into this galaxy I saw more stars in that field of view than I could see above my head,” Olivas said. “And it just put things in perspective of just how incredibly small and incredibly insignificant we truly are. Despite the fact that we think we are all that and a slice of bread because we have a little bit of money, we can build a building, whatever the case may be — I mean, we are nothing, we are just almost insignificant space dust.”

But it was also inspiring.

“The space station was a collaboration of 16 countries across our globe, getting together, working across our differences and collaborating and doing something really phenomenal …Just think what we could do on our planet by putting that same energy towards solving problems. Yet we spend so much time focusing on those things that divide us and make us different. As you look down on the planet, the only borders you see are those between land and sea. And really everything else is something imagined by humans — humans have created these boundaries. From a celestial perspective, by being able to work together, and look beyond those differences and find a way to collaborate — it doesn’t mean we have to give up our identity, it doesn’t mean we have to give up our language, our cultures, anything — it just means we have to learn to work together, and by doing so, these problems that our country faces, whether it’s starvation, water, poverty, climate, these things can be solved if we are willing to work together” said Olivas.

“Because we are out here by ourselves. This is rock. If we don’t work together to take care of our own home, and take care of each other, we are out of options. As wonderful as we are as human beings, being able to create and innovate, and have all these wonderful things that we build, if we work together, we could just do so much more.”

As Olivas looked down, he saw the landscape across which his great-grandfather, Valente, walked north 119 years earlier (29 years before federal law created the crime of illegal immigration), where he built a home and married his wife, Jesusita, with whom he’d have 18 children. What Olivas did not see was a border.

“Migrants coming to the United States are not something to be feared. And they provide a tremendous benefit to our society — they ultimately become us. Just like my great grandfather did. He came over at a time when there was no such thing as illegal immigration. It was just immigration. “

“As an astronaut, what you want to do is take space and put it into a bottle, and bring it home and share it with people because there are so many unique aspects of it you just can’t possibly describe or take photographs of,” Olivas said. “You just can’t describe it. It infuses all of your senses. But since we can’t do that, we do the best that we can — we come back, and we tell stories, and we try to convey the experience that we had, and tell the more scientific and discreet things that happened to us in space.”

All these years later, Olivas is still trying his best to convey what he saw and what he learned in space. The lesson, he believes, is about the power of diversity — not just of people, but of thought.

“The border is nothing to be afraid of,” Olivas said. “And the people at the border are nothing to be afraid of. They are just like everybody else. We are all the same. We have the same wants and hopes for our children to have a better life than we have.”

Olivas is brought to tears when he thinks about the forces of division at play that inspired a man to drive hundreds of miles south to that Walmart in El Paso and murder people because of the color of their skin, and because of the idea, perpetuated very specifically by Donald Trump, that they were invading. He is also brought to something he is not easily given to, a sense of outrage.

“It’s just offensive for anyone in this country to look at me, my family, my children and consider us anything other than Americans,” Olivas said. “In fact, I’d argue that I’m more American than the president of the United States. Because I put my life on the line for this country, in the most extreme sense. I fixed a U.S. space shuttle, Space Shuttle Atlantis, so that we could come home as a crew, to save my fellow colleagues and myself, and the program. This was after Columbia, so had we lost Atlantis coming home, where would the space program be today? Probably nonexistent. Yeah, but this Mexican-American…I did my very best to serve the United States. And for this administration to continue to demonize Hispanics to the point where Americans are being attacked, and not apologize for that, is offensive to me. He works for me. The president of the United States is employed by me, the U.S. taxpayer.”

“The episode in El Paso, I never in my wildest dreams thought it would happen in El Paso, but I knew that day was coming. People have been calling us, people who want to know what they can do, how they can help. And it’s very simple: vote.”

Other Soruce

#🇲🇽#STEM#Danny Olivas#John Daniel “Danny” Olivas#hispanic heritage month#mexican bookblr#Endeavor’s Long Journey#racism#discrimination against mexicans#mexican#hispanic#latino#mexican american#usa#united states#immigration#asylum seekers#Space Shuttle Atlantis#STS-117#NASA#International Space Station#ISS#donald trump#dump trump#mexico#TEDx talk#el paso shooting#texas#mexican history#Valente Olivas

0 notes

Text

On this day in 2011, the Space Shuttle Program came to a close with STS-135 as Atlantis touched down at Kennedy Space Center.

0 notes

Text

The Space Shuttle Atlantis seen in silhouette during solar transit, May 12, 2009.

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

"CAPE CANAVERAL, Fla. –– Space shuttle Atlantis on Launch Pad 39A is viewed across the lagoon at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida. Atlantis is targeted to launch May 12 on the STS-125 mission to upgrade NASA's Hubble Space Telescope."

Photo credit: NASA/Jack Pfaller

Date: April 18, 2009

NASA ID: KSC-2009-2756

#STS-125#Space Shuttle#Space Shuttle Atlantis#Atlantis#OV-104#Orbiter#NASA#Space Shuttle Program#LC-39A#Kennedy Space Center#Florida#April#2009#my post

91 notes

·

View notes

Text

May 8, 1989 - Atlantis on final approach into Edwards AFB, Ca after a four day mission (STS-30)

57 notes

·

View notes

Photo

closer than you think

by AllanOdyne

#photography#photoraphers#original#canon#artists on tumblr#allanodyne#canon 5d mark iii#travel#vacation#usa#america#florida#cape canaveral#kennedy space center#nasa#space shuttle#atlantis#booster#rockets#big#hugh#stunning#physics#visitor center#people#tourism#beautiful

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Launch of Space Shuttle Atlantis STS-86 - Mission to Mir Space Station

Comment: A few minutes and the space shuttle reaches the space. Just 80 km above us the infinite void called „space“ according NASA definition begins. The earth’s atmosphere is even thinner - the so-called Stratosphere ends 50 km above us.

0 notes