#structuralism

Text

Provincial Electricity North Holland (1977-82) in Alkmaar, the Netherlands, by Abe Bonnema

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm very afraid of something for Season 3. As other better researchers than I have discussed here on tumblr and elsewhere, it's very likely that the Scapegoat tradition, prevalent in ancient Judaism, provides structure for what will play out in S3. In this tradition, there are two goats. One goat is driven out into the desert to take on the sins of the people (the Scapegoat), and the other is sacrificed to God. In this metaphor, Crowley appears to be the Scapegoat, which leaves for Aziraphale the role of sacrifice.

Aziraphale has already "died" once, when he was discorporated the day of the first Armageddon, the day his bookshop burned. That day was traumatic for Crowley. He was so distraught at the loss of Aziraphale that I think if he is again faced with the possibility in S3, he will throw himself on that sword to protect his angel, won't let it happen again. He wouldn't be able to live with himself if he failed to protect his angel again.

I think this might be a prediction for Season 3, which I usually steer away from. It makes sense structurally that Aziraphale would be chosen by the Metatron to be the sacrificial goat, but also, structurally, we've already seen the angel discorporated once. I don't think Crowley will let that happen again. And I don't think Neil would, either. Crowley's going to push him out of the way. He's going to take that hit.

I don't know if I can handle Season 3.

#good omens#aziraphale#crowley#aziraphale x crowley#david tennant#neil gaiman#season 3#micheal sheen#writing#structuralism#scapegoat theory

82 notes

·

View notes

Photo

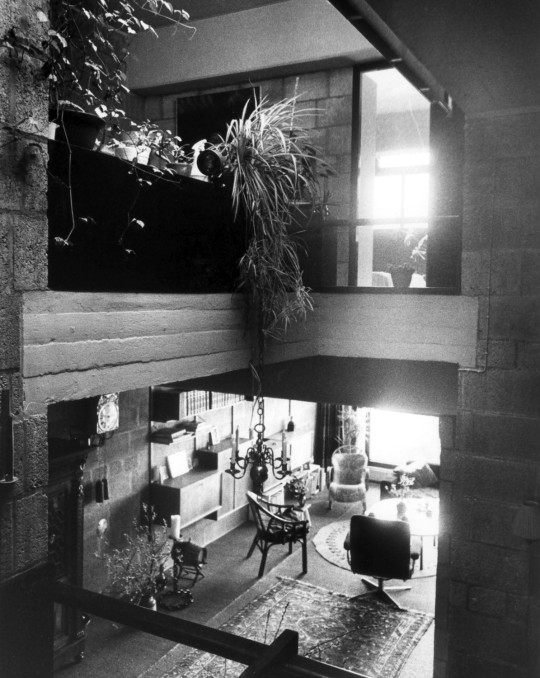

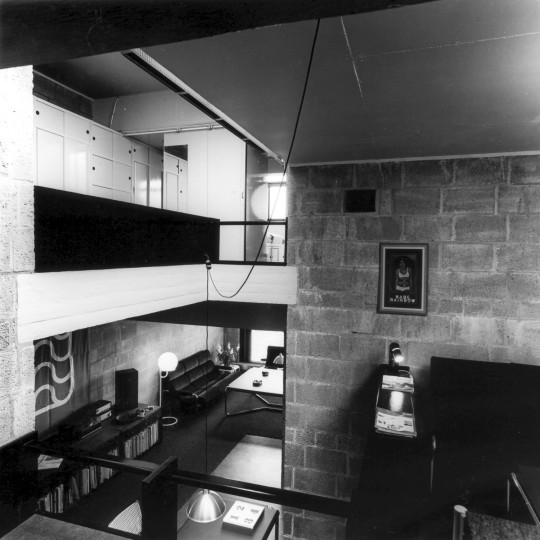

Diagoon experimental housing, Delft, Herman Hertzberger, 1967-70

174 notes

·

View notes

Text

#occult#esoteric#neo-platonism#philosophy#continental philosophy#semiotics#structuralism#cultural appropriation#religion#hermetic#qabalah#hermetic qabalah#hellenism#pagan#thelema

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reading Notes 4: Metz to Deleuze

Christian Metz’s “Some Points in the Semiotics of the Cinema” and Giles Deleuze’s “Introduction: Repetition and Difference” transitions our inquiry from semiotics and structuralism to poststructuralism and postmodernism.

How are connotations used to signify style, genre, symbol, or poetic atmosphere in film?

How is repetition different from generality, and how is repetition different from resemblance?

@theuncannyprofessoro

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

One of the great problems in the theory of fiction from Aristotle to Auerbach has been the relationship between fictional art and life: the problem of mimesis. The formalist approach to this problem, far from being a lapse into pure aestheticism, or a denial of the mimetic component in fiction, is an attempt to discover exactly what verbal art does to life and for life. This is most apparent in Victor Shklovsky's concept of defamiliarization. Shklovsky's concept is grounded in a theory of perception that is essentially Gestaltist. (And behind the Gestalt psychologists are the Romantic poets and philosophers. In the English tradition, there are passages in Coleridge's Biographia Literaria and Shelley's Defense of Poetry which clearly anticipate Shklovsky's formulation, as we shall see in chapter 6.A, below.) “As perception becomes habitual," Shklovsky notes, “it becomes automatic." And he adds, “We see the obiect as though it were enveloped in a sack. We know what it is by its configuration, but we see only its silhouette." In considering a passage from Tolstoy's Diary, Shklovsky reaches the following conclusion:

Habitualization devours objects, clothes, furniture, one's wife, and the fear of war. "If all the complex lives of many people go on unconsciously, then such lives are as if they had never been."

Art exists to help us recover the sensation of life; it exists to make us feel things, to make the stone stony. The end of art is to give a sensation of the object as seen, not as recognized. The technique of art is to make things "unfamiliar," to make forms obscure, so as to increase the difficulty and the duration of perception. The act of perception in art is an end a itself and must be prolonged. In art, it is our experience of the process of construction that counts, not the finished product.

Shklovsky goes on to illustrate the technique of defamiliarization extensively from the works of Tolstoy, showing us how Tolstoy, by using the point of view of a peasant, or even an animal, can make the familiar seem strange, so that we see it again. Defamiliarization is not only a fundamental technique of mimetic art, it is its principal justification as well. In fiction, defamiliarization is achieved through point of view and through style, of course, but it is also accomplished by plotting itself. Plot, by rearranging events of story, defamiliarizes them and opens them to perception. And because art itself exists in time, the specific devices of defamiliarization themselves succumb to habit and become conventions which finally obscure the very objects and events they were invented to display. Thus there can be no permanently "realistic" technique. Ultimately, the artist's reaction to the tyranny of fictional conventions of representation is a parodic one. He will, as Shklovsky says, “lay bare" the conventional techniques by exaggerating them. Thus Shklovsky analyses Tristram Shandy as primarily a work of fiction about fictional technique. Because it focuses on the devices of fiction it is also about modes of perception—about the inter-penetration of art and life. The laying bare of literary devices makes them seem strange and unfamiliar, too, so that we are especially aware of them.

—Robert Scholes, Structuralism in Literature: An Introduction, 1974.

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Detienne, taking as his key the well-known myth that Adonis' pregnant mother Myrrha or Smyrna (both Greek words for myrrh) was metamorphosed into a myrrh tree, from whose trunk the newborn in due time emerged, sees Adonis as essentially the fruit of an aromatic shrub, a perfume, an anti-agricultural product. His method is to find a counter-phenomenon in Attic society, in response to which the Adonia can take their significance: surely the Thesmophoria, the autumn festival in honor of Demeter at which the women of Athens celebrated the growth of food crops. Detienne finds a further, sociological opposition here: the Thesmophoria were celebrated only by the wives of Athenian citizens; the Adonia were notoriously celebrated by prostitutes. He positions Adonis and the data of his cult within various oppositional codes discernible in Greek culture-each illustrated by a diagram-that parallel one another quite precisely, replicating the same meaning in different terms: aromatically, Adonis stands for heady perfume; botanically, for profitless agriculture; socially, for seduction and extramarital pleasure. The Adonia, Detienne declares, were a celebration of infertility and fruitless sex, a spectacular illustration of the dangers of untrammeled female sexuality, serving to balance and emphasize the autumn celebration of fruitfulness and legitimate connubiality in the service of the polis.

But much evidence slips through Detienne's grid. In several versions of the birth of Adonis myrrh has no place: in our earliest his mother is one Alphesiboea ([Hes.], fr. 139 M-W); in another she is one Metharme ([Apollod.], Bibl. 3.14.3). Philostephanus of Cyrene made him the son of Zeus alone (ap. [Probus] on Verg., Ecl. 10.18).22 As for the carnival of whores, the Adoniac festivities in brothels in Diphilus, fr. 42.38-41 PCG and Alciphron 4.14.8 (based on fourth-century comedy), are to be supplemented by Aristophanes, Lys. 391-96, and Menander, Sam. 35-50, in which wives and daughters of citizens celebrate the Adonia. Most surprisingly, Detienne's theory takes only passing account of the ritual lamentation, which ancient sources make the most conspicuous feature of the festival, and in general ignores what the celebrants themselves thought of what they were doing-unless we are to imagine that the women of Athens climbed onto their roofs once a year deliberately to celebrate their own failings to the community. There was probably another reason, one which feminist studies of the cult have begun to seek.

Another assumption, however, more fundamentally flaws Detienne's interpretation. While proposing to tease an inherent meaning from Athenian cult practice by identifying the inherent correspondences and oppositions within it, Detienne fails to define a perspective more specific than a homogeneous Greco-Roman society. Adonis, for example, must have meant many things to many people at many times (even different things to the same people at different times), but Detienne's formula assumes that he meant essentially the same thing to everybody, no matter how many borders of nation, culture, language, gender, or time he may have crossed-as if any detail of the myth of Adonis tapped into one immanent meaning and could be adduced for the significance of the Athenian cult. Rhetorical motives are undifferentiated: a line of Sappho is treated equally with a line of Philodemus; the testimony of Aristophanes is put on a par with the testimony of St. Cyril. This method is programmatic and derives from Levi-Strauss, who articulates the principle thus vis-A-vis his interpretation of Oedipus: "[W]e define the myth as consisting of all its versions; or to put it otherwise, a myth remains the same as long as it is felt as such." Combining details from diverse myths of Adonis, regardless of date or provenance, Detienne treats the resulting conglomeration as a single sacred tale holding a precious key to the meaning of the ritual. But for whom does it hold meaning? For Detienne alone. Purportedly context-based, his method actually isolates phenomena from their diverse cultural uses and recontextualizes them into an artificial code that transcends the messy inconsistencies of Greek thought."

- The Sexuality of Adonis by Joseph D. Reed

#adonis#adonia#festivals#ancient greece#greek mythology#structuralism#excerpts#article#and this is why I have such a bad time reading the writings of Detienne and other structuralist classicists#not that they don't write a lot of interesting and insightful stuff#but the homogenizing of all versions of a myth (no matter the date or author or language) into one coherent account#and the extrapolation of meaning from that one ahistorical version that the author has just created#is just not something I care about#and I also feel that the interpretation of the gods from a structuralist perspective can be reductive#and necessitates the ignoring or dismissal of sources that don't fit so neatly into the proposed binary#ex: Poseidon=brute force of nature so he engenders the horse; Athena=civilization and technology so she creates the bridle to tame it#just ignore that in some sources it is Poseidon himself who invents the bridle#I mean yeah the idea does have merit#but ancient Greek mythology and religion are complex and messy and diverse and even contradictory

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Andor does not answer the questions of what governance the rebellion will offer, though for the first time we really get a glimpse at a broader ideological program than just imperial overthrow. What Andor does, instead, is show that order and rebellion are shaped by the material of life, the conditions inherited and experienced by those who will make history.

In this reading, the Empire isn’t just an engine of evil constraining the galaxy. Empire is also a structure of evil, maintained by people who show up for work, send each other memos, and manage violence as it suits their career goals. For Tarkin, as for Partagaz, doctrine of Imperial Rule isn’t the best answer, it’s simply the only answer. It’s also why they both lost."

- Kelsey D. Atherton, from "Tarkin, Revisited." Wars of Future Past, 9 December 2022.

#kelsey d. atherton#quote#quotations#star wars#andor#structuralism#systems theory#historical materialism#resistance#fascism#totalitarianism

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

#Lloyd's Building#London#architecture#photography#structuralism#not mine#England#skyscraper#Richard Rogers

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Psychosis is a certain structural relation toward language and others, and these are scarcely possible to tell apart. As enumerated by classical psychiatry, linguistic disturbances can be grouped, following Freud and Lacan, into two opposing types: on the one hand, those where the fullness of signification has the lead, and on the other those that emphasize the empty formulas. Moreover, each of these oppositions will ascribe a specific position to the other.

Such division of linguistic disturbances is of considerable more interest than a purely descriptive classification. As an illustration of this, neologisms, often regarded as the hallmark of psychosis, are not always so evident in clinical praxis because of the way that normal words can be used in a “neologistic” way. Moreover, while the psychotic neologism can be brimful of (new) meaning—as one expects—it can also be the opposite, that is, completely hollowed out, reduced to the repetition of an empty refrain.

[…]

The basis upon which the psychotic subject is able to maintain itself in normal social exchanges is typically summarized by two concepts: “suppletion” and as-if identification. […] The concept of the “as-if,” however, conjures up the wrong image: the psychotic does not know it is behaving as-if; it is the picture. The consciousness of the as-if aspect belongs to the neurotic realm, because the neurotic is always aware of not being “real,” of never fully being able to play its part and, precisely because of this, is terrified of being unmasked. In psychosis, it is all about a falling together with, a self-coinciding. Such identification is not uncommon in the treatment, when psychotic patients—often in the context of so-called “resocialization”—fully identify with the therapeutic discourse, even describing themselves to everyone as “schizophrenic”—they are literally the flesh-and-blood image of what they ingested from the Other."

— Paul Verhaeghe, On Being Normal and Other Disorders: A Manual for Clinical Psychodiagnostics

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

“If we are led to believe that what takes place in our mind is something not substantially or fundamentally different from the basic phenomenon of life itself, and if we are led then to the feeling that there is not this kind of gap which is impossible to overcome between mankind on the one hand and all the other living beings - not only animals, but also plants - on the other, then perhaps we will reach more wisdom, let us say, than we think we are capable of.”

Claude Lévi-Strauss, Myth and Meaning: Cracking the Code of Culture

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kubuswoningen (1982-84) in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, by Piet Blom

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Analytical Application 2: Structuralism and Semiotics

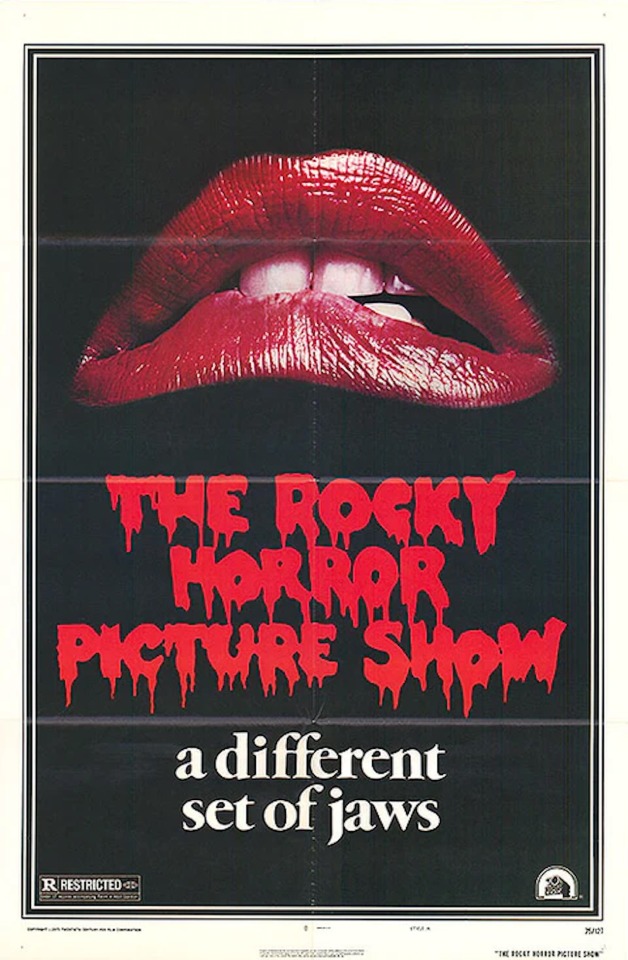

Connotation :: The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975)

Definition:

Connotation refers to the additional meaning or associations that a word or image carries beyond its literal definition. Ferdinand de Saussure, in "Course in General Linguistics," emphasizes the importance of the connotative aspect of signs. He states that the “bond between the signifier and the signified is arbitrary,” (1), also mentioning that the sign is based on “tradition” (2). This means that the associations or connotations we have with linguistic signs and symbols are based on personal experience and arbitrary societal tradition/association.

Analysis:

The poster, featuring exaggerated and sensuous lips adorned with bold red lipstick, embodies a myriad of connotations that resonate with the film's themes of rebellion, sexuality, and unconventional identity. In this context, the lips serve as a potent signifier, conveying layers of meaning through their visual representation.

The bold red lipstick, a hallmark of femininity is often used as a symbol alluding to sexuality. This symbol traditionally carries connotations of passion, desire, and empowerment. Depending on the viewer’s personal experience, this could symbolize confidence and defiance of societal norms, reflecting the film's exploration of sexual liberation and the rejection of conventional gender roles. The exaggerated size and central placement of the lips amplifies their allure and intensity, heightening the sense of desire and indulgence associated with the film's narrative.

Furthermore, the absence of any other visual elements besides the lips and the text accentuates their significance within the composition, emphasizing their role as the primary signifier of the film. This minimalist approach allows the viewer to focus solely on the evocative power of the lips and the provocative message they convey based on the symbol’s connotations.

The tagline "a different set of jaws" serves as a linguistic sign with its own pop culture and personal connotations, possibly referencing the popular film "Jaws" while also playing upon the lips (and teeth) pictured in the poster. This juxtaposition of the familiar with the unexpected captures the essence of the film's unique appeal and cult status, inviting viewers to embrace a cinematic experience that defies traditional conventions. In all, this movie poster utilizes the connotations of both symbols and signs to appeal to a certain audience and encode a message to the viewer.

(I don’t have the space to talk about the font for the title but that has its own connotations with ‘horror’ as well!)

Diegesis :: Nuns on the Run (1990)

Definition:

Diegesis refers to the narrative world depicted in a film, including the characters, events, and settings. Christian Metz describes the diegesis as “the fictional space and time dimensions implied in and by the narrative, and consequently the characters, the land-scapes, the events, and other narrative elements…” (3). Something that is diegetic is included within the film’s universe in order to add context or further worldbuilding in one way or another.

Analysis:

The film poster for "Nuns on the Run" (1990) presents an interesting interplay of diegetic and non-diegetic elements, particularly with the inclusion of a wanted poster within the poster itself. Diegesis, as defined by Christian Metz, refers to the narrative world depicted in a film, including the characters, events, and settings.

In this poster, the diegesis is primarily represented by the characters portrayed by Eric Idle and Robbie Coltrane, who are dressed as nuns hiding behind a wall as Brian Hope, Eric Idle’s character, looks into the camera. This imagery establishes the narrative premise of the film, which revolves around two small-time criminals who disguise themselves as nuns to escape from the law.

However, the inclusion of a wanted poster featuring the characters' mugshots and names (as well as the crime they committed in the film’s narrative) adds an intriguing layer to the diegesis. While the characters themselves are part of the film's narrative world, the wanted poster is a diegetic element being used for a non-diegetic purpose. It serves as a meta-narrative device, bridging the gap between the film's fictional world and the story of the movie, advertising the film’s concept. The inclusion of the wanted poster within the film along with the 4th wall break also highlights the playful and comedic nature of the film, following comedy movie poster tropes.

Overall, the film poster for "Nuns on the Run" (1990) effectively utilizes a diegetic element in a non-diegetic way to establish the narrative premise and genre of the film. The inclusion of the wanted poster within the poster adds depth and complexity to the diegesis, inviting viewers to consider the film's narrative world from a meta-narrative perspective.

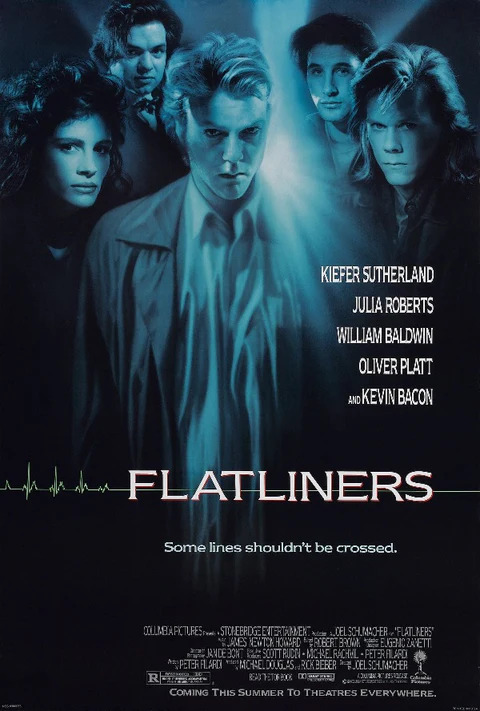

Filmic Narrative :: Flatliners (1990)

Definition:

Filmic narrative refers to the storytelling techniques employed in cinema, including the arrangement of events, characterization, and thematic development. Metz explains the filmic narrative as the storytelling techniques and structures employed in cinema to convey a coherent sequence of events, characters, and themes to the audience (4). It is made up of the techniques that are used and collocated to present the narrative to the viewer.

Analysis:

The film poster for "Flatliners" (1990) offers a glimpse into the film's narrative through its composition and imagery. The poster features a striking visual of five silhouetted figures walking across a narrow beam of light against a backdrop of darkness. This imagery immediately evokes a sense of mystery and intrigue, hinting at the film's exploration of the unknown.

The arrangement of the silhouetted figures suggests a group of characters embarking on a collective journey or quest, a common trope in narrative storytelling. The use of silhouette enhances the sense of anonymity and universality, allowing viewers to project themselves onto the characters and engage with the narrative on a personal level. The beam of light that illuminates the characters serves as a visual metaphor for enlightenment or revelation, symbolizing the transformative journey they are about to undertake.

Aside from the outfits of the ghostly, translucent characters, the heart monitor behind the title of the film implies the setting and premise of the film, with the sound of heart monitors having a strong association with medical environments. As well as medical environments, the heart monitor (particularly when it flatlines) represents death, or at the very least the stopping of the heart.

The tagline "Some lines shouldn't be crossed" adds an additional layer of narrative intrigue, suggesting that the characters' actions may have unforeseen consequences that blur the boundaries between life and death. All of these elements work together, or collocate, to present a peek into this narrative to the viewer. This is a perfect example of how filmic narrative can be utilized outside of actual filmmaking as a form of storytelling. Although the poster only alludes to the film’s themes and story, by analyzing the many elements in the poster, we can extract a form of the narrative that draws us in further.

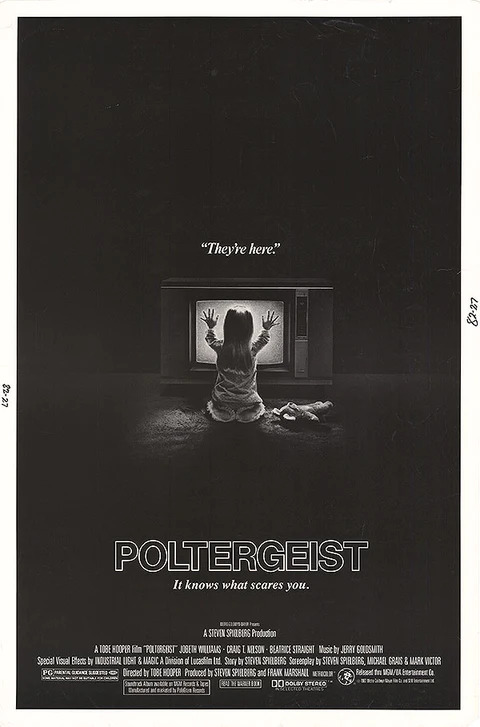

Language (cinema) :: Poltergeist (1982)

Definition:

Language in the context of cinema and film refers to the unique visual and auditory elements used to convey meaning and evoke emotions. Christian Metz explores how cinematic language utilizes various techniques such as editing, framing, and sound design to communicate with the audience (5), forming its own kind of film language!

Analysis:

The film poster for "Poltergeist" (1982) exemplifies the concept of language in cinema or filmic language as defined by Christian Metz, emphasizing the unique visual and auditory elements used to convey meaning and evoke emotions within the cinematic medium. The poster employs a combination of visual elements and symbolism to communicate the eerie and supernatural themes of the film, effectively engaging viewers and setting the tone for the cinematic experience.

The poster features a young girl sitting in front of a static-filled television screen, her hands reaching out towards, if not touching, the screen as if drawn into its depths. This imagery serves as a powerful visual representation of the film's central premise, which revolves around a family haunted by malevolent spirits through their television set. The static-filled screen symbolizes the intrusion of the supernatural into the domestic space, blurring the boundaries between reality and the unknown.

It is also worth noting that static has a very notable and distinctive sound. When one thinks of television static, they likely think of the sound that goes along with it. This use of a symbol with connotations of sound is a clear use of filmic language to convey the uncanny themes of the film’s narrative.

The poster for "Poltergeist" utilizes visual elements such as lighting, composition, and symbolism to convey meaning and evoke emotions in the viewer, all elements of the language of cinema. The static-filled television screen serves as a visual signifier of the supernatural phenomena depicted in the film, while the girl's body language communicates fear and fascination due to the uncanny nature of her pose. Through its use of visual language, the poster effectively sets the stage for the cinematic experience, inviting viewers to watch the film and properly engage with the language of film that it utilizes.

Sign :: Jackie Brown (1997)

Definition:

A sign in cinema refers to any element within the film that carries meaning, including images, sounds, and notably, language. Ferdinand de Saussure defines a sign as a combination of a signifier and a signified. He argues that signs are arbitrary and derive their meaning from cultural conventions and tradition (6).

Analysis:

The film poster for "Jackie Brown" (1997) offers a plethora of signs to analyze. The central signifier in the poster is the image of Pam Grier as the titular character, Jackie Brown, positioned prominently at the forefront. Grier's confident stance and assertive gaze serve as visual cues that signify Jackie's strength and resilience as a character. She embodies the archetype of the empowered female protagonist, a key signifier of the film's narrative focus on themes of agency and empowerment.

Accompanying Jackie Brown are signs that provide additional layers of meaning and context. The presence of other characters, such as Robert De Niro's Louis Gara and Samuel L. Jackson's Ordell Robbie, serves as signifiers of the complex web of relationships and conflicts that drive the film's plot. Their positioning and expressions convey subtle hints about their roles and motivations within the narrative.

Moving away from the film’s narrative and toward the signs imbued within the poster’s text, actors’ names are highlighted in a bright red against the gray background, with the director Quentin Tarantino’s name outlined by a golden bubble. With his name and the colors and font as the signifier(s), the signified meaning of this highlight is Quentin Tarantino’s prestige; effectively branding the film as prestigious, given his history of critical hits.

Overall, the film poster for "Jackie Brown" effectively utilizes signs to convey key aspects of the film's narrative, characters, and even to highlight the creators. Through the strategic arrangement of visual elements, including characters, color, and typography, the poster engages viewers and encodes messages about the film and its background and creative process.

1) Ferdinand de Saussure. Course in General Linguistics. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1966, 67.

2) Ibid, 74.

3) Metz, Christian. "Some Points in the Semiotics of Cinema" in Film Theory and Criticism, 68. Edited by Leo Braudy and Marshall Cohen. New York, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

4) Ibid, 68-70.

5) Ibid, 67.

6) Ferdinand de Saussure. Course in General Linguistics. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1966, 67-75.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Market Street

#photographers#photographers on tumblr#original photographers#submission#original photography on tumblr#original photography#Street Photography#bw photooftheday#bw#contrast#photography#Architecture#city#80eastdesign#original photography blog#structuralism

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Quote of the Day:

Judith Butler's gripping account of the evolution of the post-structuralist understanding of power in social relations

The move from a structuralist account in which capital is understood to structure social relations in relatively homologous ways to a view of hegemony in which power relations are subject to repetition, convergence, and rearticulation brought the question of temporality into the thinking of structure, and marked a shift from a form of Althusserian theory that takes structural totalities as theoretical objects to one in which the insights into the contingent possibility of structure inaugurate a renewed conception of hegemony as bound up with the contingent sites and strategies of the rearticulation of power.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

History, Narrative, and the Cybernetic-Structuralist Database

Is what Roland Barthes called the “structuralist activity” an algorithm? Structuralism certainly seems to proceed, in its various instantiations, in an algorithmic manner, setting up rules that could be used to process any data loaded into the memory of literary analysis. Barthes defines the "activity" as “the controlled succession of a certain number of mental operations” (1963, 214). For structuralism, these are primarily operations of decomposition and recomposition, taking “the real” as an input, “decomposing and recomposing” it in an operational form to be worked on by the new literary scientists (215). An algorithm, strictly speaking, is a finite set of explicit and definite steps that takes an input and yields an output (Knuth 1997, 4–6). Of course, the “structuralist activity” is not literally an algorithm—its steps are by no means definite, even within the oeuvres of individual authors—but it does emphasize machine-like operations, foregrounding the ways in which it formalizes its concepts: by means of measure, selection, permutation, binary opposition, code, unit, function, and so forth, all terms which would not have been commonly found in traditional studies of literary language, which was largely philological and rhetorical (what Barthes calls the “old Rhetoric”). The “new Rhetoric” of structuralism was an attempt to confront “the new semiotics of writing,” and the “modern text, i.e., the text which does not yet exist” (Barthes 1985, 11).

The structural analysis of the “modern text” turns out to be closely—though not exhaustively or exclusively—engaged with the digital and the computational: a digital humanities avant la lettre. It is not only coincidentally similar in its broad outlines to developments in algorithmic and information-technological thinking, but actively drew on such thinking, transcoding it into cultural and literary studies (and at times subverting it, by extending it to an absurd degree). The foundational texts of structuralist narratology, in particular—such as those published by the journal of the Centre d’études des communications de masse [Center for the Study of Mass Communications] (CECMAS) at the École Pratique des Hautes Études in Paris, authored by theorists like Barthes, Claude Bremond, Gérard Genette, Tzvetan Todorov, Umberto Eco, A.-J. Greimas, Christian Metz, and others—introduce a database logic that sometimes seems to threaten the epistemic dominance of narrative, creating anxieties about the disappearance of historical meaning. This tension between databases and narratives, which Lev Manovich emphasizes much later in his book The Language of New Media (2001), is of course still relevant today, amidst major expansions of data science, artificial intelligence, algorithmic culture, and computational literary studies. A return to the history of structuralism and semiology and its genesis in what Ronald R. Kline calls the “cybernetics moment” reveals that much of the cultural-technical background has been lost in the reception of these innovative twentieth-century approaches.

Bernard Dionysius Geoghegan has recently shown (2023) how so-called French structuralism emerged from a circuit of trans-Atlantic exchange between the human sciences in Europe and the new “universal sciences” of communication and control in North America (cybernetics, information theory). European émigrés like Roman Jakobson and Claude Lévi-Strauss were among the first to popularize the hybridization of Saussurean linguistics with these new sciences: Jakobson with his reinterpretation of the Shannon-Weaver model of communication (channels and messages, senders and receivers), and Lévi-Strauss with his ambitions of organizing the large-scale storage and processing of (largely endangered) myths. Both received support from major US private philanthropic and government institutions, such as the Rockefeller Foundation and the CIA-founded Center for International Studies at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Later, in the 1960s, scholars like Barthes, responding to the technocratic, scientistic ambitions of the French state and its modernizing universities, would also take up cybernetic-structuralist thought. But they would do so more ironically than their predecessors. CECMAS, founded in 1960 by sociologist Georges Friedmann (with assistance from Barthes, Edgar Morin, and Violette Morin), became a launch pad for what Geoghegan calls “crypto-structuralism,” a retranslation of cybernetics and information theory, undertaken after these ideas had already been circulating between the US and France for around a decade. This loose group, which included Jean Baudrillard and Julia Kristeva among those already mentioned, did not reject cybernetics altogether, as many of its peers did. But it also did not import cybernetic concepts wholesale. In the writing of “crypto-structuralists” like Barthes, as we have already begun to see, there is a historicizing tendency that suggests that these thinkers may have viewed cybernetics as an interesting and useful apparatus for contending with a period of rapid information-technological change, and not necessarily as a universally applicable strategy.

One of the most influential issues of Communications, the journal of CECMAS, is the 1966 issue on narrative (“Recherches sémiologiques : l'analyse structurale du récit”). Yet narrative is largely absent from the North American communications research that CECMAS convened to study. Information theory and cybernetics are not theories of narrative; in some ways, they are antithetical to traditional concepts of narrative. The information theory of Shannon and Weaver, first published in 1948, consists of a set of five elements: an information source, a transmitter, a channel, a receiver, and a destination. A message from the source is “selected” and encoded into a technical signal, transmitted along an insulated channel, decoded by a receiver, and arrives, reconstituted, at its destination. According to this model, the channel is ideally always open, and noise-free. Similarly, cybernetics, at least as articulated by Norbert Wiener, does not deal with narratives but time series and feedback loops, seeking to develop a science of the “real-time” prediction of future behavior from past behavior in the direction of a system. Information theory and cybernetics are both probabilistic: they are oriented toward the optimization of systems according to patterns that are statistically likely. Where narrative is a recounting, these are systems of counting.

But the structural narratologists show us that recounting and counting are not necessarily so foreign to one another, or at least that it may be worth modeling the former in terms of the latter, as a kind of experiment in translation. Barthes, in an early statement on CECMAS in the social history journal Annales, uses terminology from information theory to describe the primary concept of structural analysis: the unité informative, the “smallest component element of a set.” CECMAS’s project, according to Barthes, is to investigate the ambiguity of this unit of information, which is two-sided, both quantitative and qualitative, statistical and structural, numerical and functional. It is not a matter of choosing between these two alternatives, says Barthes. Rather, “both paths are open to the mass-media researcher: such is the breadth and novelty of the work ahead” (1961, 992; my translation). Accordingly, the statistical thinking associated with information theory and cybernetics (to which we might also add game theory, decision theory, and operational research) consistently makes its way into the narratological work done by the structuralists: more or less all structural analyses of narratives begin by pronouncing the need for compression algorithms or source-codes, sets of rules that would allow us to know how narrative works without needing to read each and every narrative (an eternal task). In the Saussurean tradition, instead of following narratives primarily on the diachronic axis (as paroles), structuralism transforms them into relations on the synchronic axis (as langue). In the vocabulary of Shannon and Weaver, we might view this as the optimization of a narratological apparatus according to the “statistical structure” of narratives.

In his “Introduction to Structural Narratology” (1960), Barthes foregrounds structuralism’s idiosyncratic approach to narrative. “It has already been pointed out that structurally narrative institutes a confusion between consecution and consequence, temporality and logic. This ambiguity forms the central problem of narrative syntax. Is there an atemporal logic lying behind the temporality of narrative?” (98) An “atemporal matrix structure,” as Lévi-Strauss calls it, absorbs chronological succession. “Analysis today,” Barthes continues, “tends to ‘dechronologize’ the narrative continuum and to ‘relogicize’ it . . . the task is to succeed in giving a structural description of the chronological illusion—it is for narrative logic to account for narrative time” (99). In the same issue of Communications, Gérard Genette, Tzvetan Todorov, Umberto Eco, and Claude Bremond concur: narratives are “artificial,” full of “exclusions and restrictive conditions” (Genette 1976, 11); they are “games” or “play situations” (Eco, 155); “networks of possibilities” (Bremond, 388). They are not just continuous passages in time that readers or viewers must progress through; they are also structures in which units are correlated to other units, and beyond which these structures might be correlated to other structures.

What the structuralists discover is that it no longer makes sense to claim that narrative is fluid, continuous, analog, “natural.” Narrative is a complex operation of coding and transcoding, of organizing many time series in terms of many other time series, of decision trees, of anachronisms, focalizations, groupings, frequencies, speeds, and so on. This discovery, I would argue, is historically specific, conditioned not only by the narratologist’s modern objects (Genette’s À la recherche du temps perdu; Eco’s James Bond) but also by a techno-social situation: a Cold War context of burgeoning information capitalism and modernizing universities, the beginning of what Jean-François Lyotard would in 1979 call the “postmodern condition.” It seems that structuralist theorists were, with some exceptions, conscious of this conjuncture, and were working to develop a project adequate to it, under the political and economic pressures of the postwar period.

Lyotard would refer to a “crisis of narratives,” in which “the narrative function is losing its functors, its great hero, its great dangers, its great voyages, its great goal.” Narrative, under the postmodern conditions of information societies, is “dispersed in clouds of narrative language elements—narrative, but also denotative, prescriptive, descriptive, and so on” (xxiv). But already in 1966, Genette was writing about the “end of narrative.” In “Frontières du récit,” also published in the narratology issue of Communications, Genette asks where the boundaries of narrative might lie. Is narrative really a ubiquitous, all-encompassing phenomenon, something totally naturalized and even epistemically privileged in human societies? (“It is simply there, like life itself,” says Barthes [1977, 79].) How can we address it without determining where it ends? Where are the thresholds that distinguish narrative from non-narrative forms? Genette will suggest that narrative has both internal and external boundaries that increasingly seem to threaten its integrity as a universal, natural, transhistorical organization.

He first addresses the classical distinction in Plato and Aristotle between diegesis (narrative) and mimesis (imitation), which he decides is not applicable to modern literature (because it is without oral performance). Examining the distinction between narrative and description, Genette proposes that modern literature is in fact almost entirely narrative, with description as a kind of enclave, an internal space that can occasionally be distinguished from the events and actions of narration but does not break out of narrative entirely. It creates a mixture. (This is because for modern literature there is no “rigorous synchronicity” between the succession of text and the events it relates, as there is in the oral reading of a dialogue, for instance [7].) Description is not really one of narrative’s major modes, but must be considered “more modestly as one of its aspects” (8). Even this tentative distinction between narrative and description, Genette insists, is a rather recent development—in European literature, description gradually begins to appear within narrative in an “evolution of narrative forms” by which the proliferation of “ornamental” and later “signifying” description merely “reinforces the narrative’s domination (at least until the beginning of the twentieth century)” (6). We may find this periodization somewhat problematic, but Genette’s point is that the “narrative-descriptive unit” has undergone change, and might be, at some point, broken (7).

It is finally the external boundary of narrative, the “vague murmur” of discourse, ongoing and ambient, without closure, without narrators, which Genette recognizes as the source of a potential break. Discourse, not narrative, is “the natural mode of language, the broadest and most universal mode, by definition open to all forms” (11). Narrative is a particular form, a particular codec, as it were. Genette concludes: “Perhaps narrative, in the negative singularity that we have attributed to it, is, like art for Hegel, already for us a thing of the past which we must hasten to consider as it passes away, before it has completely deserted our horizon” (12).

In Metaphilosophy, published in 1965, Henri Lefebvre critiques structuralism’s predilection for claims like these. He makes the association between “structuralist activity” and the “cybernetic rationality” of automata, information theory, and digital computers explicit (179). Lefebvre observes “the dawn of a ‘worldview’ based on a linkage between structural linguistics, information and communications theory, and perception theory” (179). The philosophy of this worldview, for Lefebvre, is structuralism. “Structuralist activity,” he writes, “is thus always bound up with a technology. It combines two fundamental operations: dissection (into discrete units, atoms of meaning) and arrangement [agencement].” (Lefebvre is glossing Barthes’s characterization in “The Structuralist Activity,” published two years prior.) “The structural man,” therefore, “is the man of technology and technicity” (173). The terms technology and technicity do not appear in Barthes’s essay, but it is clear to Lefebvre that the structuralist activity is a technique: the encoding and decoding of messages, as described in information theory and communications engineering. The real—the object of analysis—is an information source, discretized so that it can be regenerated. For Lefebvre, this makes structuralism essentially computational: it “separates, divides, classifies (into genres and kinds), formal differences, paradigms, conjunctions and disjunctions, binary oppositions, questions that is answers by a ‘yes’ or a ‘no’” (176). It is a digital philosophy, like that of Gottfried Leibniz or Ramon Llull, an ars combinatoria which would suppose that all beings can be constructed from the combination of zeroes and ones.

Lefebvre’s fundamental anxiety—and this may be typical of critiques of both structuralism and of cybernetics—has to do with the apparent abolition of the narration of history. Structuralism, which is for Lefebvre the philosophy of technocratic management, seems to imply a “liquidation of the historical.” With the “cybernetizing of society,” there is no longer any future in the historical sense. “We would enter a kind of eternal present, probably very monotonous and boring, that of machines, combinations, arrangements and permutations of given elements” (178). Temporality itself “disappears into that of entropy . . . Along with time, it is history that disappears in the world, or acquires a new aspect, opening onto a kind of technological temporality without history, or with its only history that of combinations between technological operations” (179).

But history is not only a succession of contents; it is also a succession of forms, and a succession of cultural techniques that produce forms. The structuralists were aware of their position within a modernity in which certain techniques impressed these forms upon them, the forms that populate their own analyses: tables, trees, formulas, IBM punchcards, filing cabinets, index cards, games. These are the media of structuralism by which midcentury thinkers began to conceive narrative as subordinate to databases, a conception which today seems quite prophetic. Even if we accept a thesis like Lefebvre’s (that structuralism is the expression of an annihilation of historical time), to reject structuralist thought undialectically, or at least without viewing it as a moment that the human sciences must pass through, would itself be an ahistorical decision. Frederic Jameson’s assessment from 1972 still resonates:

To say, in short, that synchronic systems cannot deal in any adequate conceptual way with temporal phenomena is not to say that we do not emerge from them with a heightened sense of the mystery of diachrony itself. We have tended to take temporality for granted; where everything is historical, the idea of history itself has seemed to empty of content. Perhaps that is, indeed, the ultimate propadeutic value of the linguistic [and here we might add computational] model: to renew our fascination with the seeds of time. (xi)

Structuralist narratology’s “digitization” of narratives was a response to a digitization already in progress in post-industrial societies. That the mainstream of our culture continues to be characterized by increasingly automated recombinations of elements from massive databases, by statistical methods that generate, classify, and order the “content” that makes up so much of consumption today, only underscores the propadeutic value of the structuralist moment, now more than half a century old.

References

Barthes, Roland. 1961. “Le Centre d’études des communications de masse (le CECMAS),” Annales. Histoire, Sciences sociales 16(5): 991–992.

———. (1963) 1972. “The Structuralist Activity.” Pp. 213–220 in Critical Essays, translated by Richard Howard. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press.

———. (1966) 1977. “Introduction to the Structural Analysis of Narratives.” Pp. 79–124 in Image Music Text, translated by Stephen Heath. New York: Hill and Wang.

———. 1985. The Semiotic Challenge, translated by Richard Miller. New York: Hill and Wang.

Bremond, Claude. (1966) 1980. “The Logic of Narrative Possibilities [La logique des possibles narratifs],” translated by Elaine D. Cancalon. “On Narrative and Narratives: II.” New Literary History 11 (3), 387–411.

Bowker, Geof. 1993. “How to Be Universal: Some Cybernetic Strategies, 1943–70.” Social Studies of Science 23 (1): 107–127.

Eco, Umberto. (1965) 1984. “Narrative Structures in Fleming [James Bond: une combinatoire narrative],” translated by R. A. Downie. Pp. 144–172 in The Role of the Reader: Explorations in the Semiotics of Texts. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Genette, Gérard. (1966) 1976. “Boundaries of Narrative [Frontières du récit],” translated by Ann Levonas. New Literary History 8 (1): 1–13.

———. (1972) 1980. Narrative Discourse: An Essay in Method, translated by Jane E. Lewin. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Geoghegan, Bernard Dionysius. 2023. Code: From Information Theory to French Theory. Durham, NC and London: Duke University Press.

Jameson, Fredric. 1972. The Prison-House of Language. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Kline, Ronald R. 2015. The Cybernetics Moment: Or Why We Call Our Age the Information Age.

Knuth, Donald. (1968) 1997. The Art of Computer Programming, Vol. 1: Fundamental Algorithms. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Addison-Wesley.

Lefebvre, Henri. (1965) 2016. Metaphilosophy. London and New York: Verso Books.

Lyotard, Jean-François. 1979. The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Manovich, Lev. 2001. The Language of New Media. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

1966. “Recherches sémiologiques : l’analyse structurale du récit [Semiological Research: The Structural Analysis of Narrative].” Communications 8.

Rosenbluth, Arturo, Norbert Wiener, and Julian Bigelow. 1943. “Behavior, Purpose and Teleology.” Philosophy of Science 10 (1): 18–24.

Shannon, Claude and Warren Weaver. 1948. The Mathematical Theory of Communication. Urbana, IL: The University of Illinois Press.

Wiener, Norbert. 1948. Cybernetics. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

6 notes

·

View notes