#subeshi

Text

Nampō Roku, Book 7 (68): Serving Shōro [松露] During the Meal.

68) During the meal service, shōro [松露] were [sometimes] brought out¹. This was a famous item [harvested] from the pine-barrens [around Hakata]². [Ri]kyū was taught how to prepare them by an old man from the area -- because, among the various kinds of plants, there are some that are poisonous [so one must always be careful in this regard, especially when visiting an unfamiliar area]; [however, the old man told Rikyū that] shōro contain nothing poisonous³.

Regardless of whether they are large or small, they are [first] lightly scored with a blade; and after being boiled [in broth], they should be eaten⁴.

Because they can spoil easily, cases where [the shōro] have been infiltrated by rot must be identified, so it is said⁵. That [spoiling] is certainly a possibility⁶.

As for this old man, he was well known as the first chef of the port of Hakata; and this person was called Kamichi Tōgo. He also practiced tea -- such was [Ri]kyū’s story⁷.

_________________________

¹Ryōri ni shōro wo dasu [料理ニ松露ヲ出ス].

Shōro [松露] is the Japanese name for the ectomycorrhizal fungus (a fungus that forms a symbiotic relationship with the roots of certain species of trees -- in this case Pinus thunbergii, the Japanese black pine, which populates the seaside pine-barrens of Kyūshū*) Rhizopogon roseolus, generally classified as a sort of truffle. The truffle is the fruiting-body of the fungus.

Immature shōro (which are considered more desirable) are pure white inside, while the mature truffles range from pink to reddish-brown to a pale violet-pink. This variety of truffle can be up to 1-sun in diameter.

When used as food, the truffles are washed with diluted salt water†, scored with a blade or sliced, and then either boiled in broth (as one ingredient in the nimono [煮物] course), grilled with salt (served as the yaki-mono [燒き物] course), or added to chawan-mushi [茶碗蒸し] (as the mushi-mono [蒸し物], served near the end of the meal‡).

__________

*In the uplands, Rhizopogon roseolus is also associated with Pinus densiflora, the Japanese red pine.

†Apparently to disinfect the shōro, since they grew underground (and so would be considered inherently unclean).

Saltwater, the reader will recall, was also used to disinfect the floor of the setchin.

Apparently actual seawater was preferred for such purposes -- though it could be fabricated artificially by dissolving a quantity of sea salt in warm water, in places where natural seawater was not available locally.

‡In the more elaborate version of kaiseki-ryōri that became popular during the Edo period (and remains the usual way to serve this meal today).

²Ka no matsu-bara no meibutsu nari [カノ松原ノ名物也].

Ka no matsu-bara [かの松原], “those pine-barrens,” is referring to the pine-barrens in the area of Hakata.

Ka no matsu-bara meibutsu nari [かの松原の名物なり] means (the shōro) are a specialty of the pine-barrens of that area.

³Tokoro no rōjin, Kyū ni oshie-mōshikeru ha, subete kusabera-no-rui doku ari, shōro doku-nashi [所ノ老人、休ニ教ヘ申ケルハ、スベテクサベラノ類毒アリ、松露毒ナシ].

Tokoro no rojin [所の老人] means an old man of the area. He was a native of Hakata.

Kyū ni oshie-mōshikeru [休に教え申しける] means he taught Rikyū (about the shōro).

Subete kusabera-no-rui doku ari [すべて草片の類毒あり]: subete [すべて] means among every kind (of vegetables), within the entire category (of vegetables); kusabera-no-rui [草片の類]* means the category of vegetables that exist (referring to the seeds, roots, stems, leaves, bulbs or tubers, flowers, or fruits that could be used as vegetables); doku ari [毒あり] means poisonous (varieties) exist.

Shōro doku-nashi [松露毒なし] means shōro have no poisons; shōro are nontoxic.

___________

*Again the kanji rui [類], which we find only in this group of entries dating from near the end of the seventeenth century.

⁴Sare-domo dai-shō tomo ni, sukoshi-zutsu katana-me wo irete, nite tabe-subeshi [サレドモ大小トモニ、少ツヽ刀目ヲ入レテ、煮テ食スベシ].

Sare-domo [然れども] means though (something) may be so, be things as they may -- in this case regardless of whether the shōro are large or small....

Sukoshi-zutsu katana-me wo irete [少ずつ刀目を入れて] means the shōro are scored lightly with the blade of a knife.

Nite [煮て] means after they have been boiled (in broth).

Tabe-subeshi [食すべし] means they should be eaten.

⁵Shizen ni doku ni ataru ha, doku-ke komorite no koto nari to iu-iu [自然ニ毒ニアタルハ、毒氣コモリテノコト也ト云〻].

Because of the repeated use of doku [毒], which literally means poison, this sentence seems to contradict what we were told in footnote 3. Here, however, doku is referring to the shōro having spoiled, having become rotten internally.

Shizen ni doku ni ataru [自然に毒に當たるは] literally means (if the shōro) have naturally been stricken with toxicity. Tanaka Senshō explains that this sentence means the shōro have gone bad*.

Doku-ke komorite no koto [毒氣籠りてのこと] means that they have been infiltrated by poisons (in other words, started to deteriorate from within).

__________

*In his commentary, he wrote:

Jissai, yo mo kono shōro wo chanoyu ni shiyō-shita ga, shin-sen nari to omou-shina de mo, watte-miru to, nakami ga fushoku shite-iru mono de, wari-ai ni fuhai ga hayai. Yue ni marude ha chotto kiken ni omowareru. Shizen, hōchō-me wo ireta no ga anzen de aru. Doku-ke komoru to iu no ha, kono fushoku no ba-ai wo iu no de ha nai ka

[実際、予も此松露を茶の湯に使用したが、新鮮なりと思ふ品でも、割って見ると、中味が腐蝕して居るもので、割合に腐敗が早い。故に丸では一寸危険に思はれる。自然、庖丁目を入れたのが安全である。毒気篭ると云ふのは、此腐蝕の場合を云ふのではないか].

This means, “once, when I actually going to use these shōro for chanoyu, even though I thought they were fresh, when I broke one open and inspected it, the inside was rotten. They seem to spoil relatively quickly. For this reason they seem to be at least a little dangerous. Naturally, if a kitchen knife is pushed in, it will be safe [since doing so will reveal if it is spoiled on the inside]. The phrase doku-ke komorite [毒氣籠りて] refers to this situation where they have begun to spoil, doesn’t it?”

In the last sentence, Tanaka cannot help but his doubts -- occasioned by the conflict between this sentence and what we were told in footnote 3.

⁶Sa mo aru-beshi [サモアルベシ].

Sa mo aru-beshi [さもあるべし] means “that (the shōro’s spoiling) is something that is certainly possible” -- so they should be checked carefully.

⁷Kono rōjin ha, Hakata-no-tsu dai-ichi no hōchō-nin, Kamichi Tōgo to iu-bito ni te, cha wo mo tatetari to Kyū no monogatari nari [コノ老人ハ、博多ノ津第一ノ庖丁人、神治藤五ト云人ニテ、茶ヲモ立タリト休ノ物語也].

Kono rōjin [この老人は] means the old man who taught Rikyu about shōro.

Hakata no tsu [博多の津] means in the area of Hakata port. The focus of the city-state was its harbor, and the main thoroughfare and ceremonial route ran from the great Enkaku-ji* directly across the whole enclave to the seawall and wharves.

Dai-ichi no hōchō-nin [第一の庖丁人] means he was the first, or most esteemed, professional chef (in Hakata).

Kamichi Tōgo to iu hito [神治藤五と云う人] means this person was known as Kamichi Tōgo†.

Cha wo mo tatetari [茶をも立てたり] means Kamichi Tōgo also practiced chanoyu.

To Kyū no monogatari nari [と休の物語なり] means this‡ was Rikyū’s story.

__________

*According to Kanshū oshō-sama, the original Enkaku-ji stood on the site currently occupied by the Hakata train station. The temple was burned down by the Imperial Army in the 1930s, apparently in retaliation for the refusal of the Abbot to hand over the original copy of the Nampō Roku. (The Shū-un-an, at the Nanshū-ji in Sakai, was looted and burned down, again by the Imperial Army -- according to the highly placed monks I spoke with there -- around the same time.)

The current Enkaku-ji was rebuilt during the 1950s, on ground obtained from the neighboring Shōfuku-ji (originally the parcel of land was a graveyard for non-tonsured individuals affiliated with the temple; it was located outside the temple walls).

†Shibayama Fugen’s toku-shu shahon gives his name as Kaminoya Jitōgo [神野治藤五].

Tanaka, meanwhile, completely discredits Kamichi (as the name is written in the Enkaku-ji text), concluding that the family name should be pronounced either Kamiya or Kaminoya. However, he also adds that, as a personal name, Jitōgo [治藤五] sounds very strange -- though he does not really offer us any alternatives.

‡Probably referring to the entire episode that is discussed in this entry; though, grammatically, it could simply refer to the statement that Kamichi Tōgo (or Kaminoya Jitōgo) practiced chanoyu.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

twinkling mermaid lyrics

i cant fuckinf find the romaji

umi no sokote

hitori ki mitai o omosuki no takanaku

koko ga watashi no sekai

ikiteki kauna

nanaka no kokoro ni

urete usa urareteru kanjo

itsuka te ni irerareru

soshinjiteta

itsumate mo kurayami no naka

sore ja nani mo kairarenai yo

sora te to shikatsuku yo ni

te o nobashita yo

hikari sasu

saki ni todoku hatsu

to oyoite noboru

wakana nai mirai dake do

susumu iyai no michi wa nai kara

okotsureta

hisekisashi no meta

teshi tsuka ni miru

hajimete no

mukuro ni tsutao

kore wa hito no deai

kimi ga hanashite

fureta no takusa

no mono o katari

ame mo kore mo subeteta

kirameiteita

kochi gena koi ga hibite

shitse uto futari iga o naukabu

yoroko ni fukuretagau

komenatanoshi

hajimete no sekai kokoro omoru

hikan ga atsurabu

kimi to iru

hibiga tsuru to

tsuzuke mai no tomoteta

toki no sana

wakatsu mitsuketa yo

watashi no ibasho

kimi ga kera

toshi o kasarete

watashi omokoshiteruku

hikari sasu

saki o mitsuketa yo

watashi no ibasho

wakananai

mirai shinji

koko ni itoki meta subeshi ta yo

demo kimi wa

kokoro mo teku

muhatsu no nai no ne

hajimete no

mukuro ni kita

kore ga kinto no wakabe

nani ga no watashi tsumiuku

0 notes

Text

Historic Beginnings of Modern Witch Style

We all know the archetype and style of the witch woman today, but ever wondered where does it all stem from? Here are some facts behind the historic beginnings of witch style...

Earliest coned shaped hats were found in China. The remains of mummies found there were of sisters accused of practicing magic in Turfan between 4th and 2th century BCE.

Witches of Subeshi - click here to check out the story and the pics of the mummies. Not for the faint of heart.

In the Middle Ages in Europe people associated pointed hats with Jewish religion and... Satan. In Hungary for instance during the Witch Hunts, Jewish people were accused of practicing devil worship and magic, and were made to wear the horned skullcap.

In America, the Quakers were accused by Puritans of being devil worshipers even though the Quaker styled hats back then didn’t match the accusations.

In medieval Europe, women who brewed beer were considered and accused of being witches, and they actually did wear pointed hats similar to those we see today in media.

A 16th century English prophetess called Mother Shipton wore a tall, conical hat and gave out some surprising predictions regarding the arrival of the internet. Her real name was Ursula and she had a large, crooked nose, hunched back and twisted legs. Her mother had to give her up to the local family because she was completely alone and raised the girl in a cave of all places for two years before securing her a better place.

Since people mocked her early on because of her appearance, she went back to the forest and near the cave where she was raised and got interested in observing and studying nature. She made remedies from herbs and plants, and later on realized she could predict the future.

She is believed to have foretold the Black Death, the Great Fire of London, the defeat of the Spanish Armada and the end of the world. And the internet.

“Around the world, men’s thoughts will fly. Quick as the twinkling of an eye.”

In parts of East Europe before Christianity took off there, the pagan Slavs used to consider female principle of creation and death as rather important. Over time, to end the reign of old Gods and Goddesses, fear based stories and specifically made religious propaganda of women being seduced by the devil turned things around. Back then and even today, women were often called to nurse the elderly or the dying. It didn’t take much to point and accuse the women of being the ones inflicting death itself though.

According to History.com, the earliest depiction of a witch riding a broom dates to 1451 in the manuscript of a French poet by the name of Martin Le Franc. Two women with brooms are depicted as Waldensians who were a Christian sect that accepted women as priests and were thus in part branded as heretics by the Catholic church.

A pagan fertility ritual among rural folk in Europe involved jumping over a stick or a broom and or dancing during full moon for the growth of their crops.

Another possible reason why witches were depicted flying with brooms were some historical findings which say that witches made herbal ointments and applied them to their intimate areas or skin to avoid getting an upset stomach and to get high from it.

“ Priests frequently leveled accusations of sexual magic at European women. The penitential books refer often to love potions. [Rouche, 523] But sexual witchcraft went beyond those, or even the dreaded (and popular) impotence magic. Early medieval writers show that women were using herbal medicine and witchcraft to control their own fertility and childbearing. Bishops in France, Spain, Ireland, England and Germany enacted canons forbidding women to undertake means of controlling their own conception, herbal and ceremonial, as well as to end pregnancies or perform abortions.

Though the Church described them as sorceresses, the wisewomen, herbalists, midwives and elders belonged to a spiritual tradition rooted in the land. Mother Earth gave healing herbs that restored life to the body, balanced it, healed wounds or disease, promoted conception or prevented it. Women who desired children prayed to ancient goddesses and petitioned them at holy rocks and pools. These animist divinities were invoked in childbirth, to help the mother and strengthen the newborn, for knowledge about how to conceive and how to not conceive children. (Often they ended up transformed into Christian saints, allowing a seamless transition of their rites and symbols.) The pagans knew the cycles of life's renewal to be infinite, and appealed to the same deities in death.“ Suppressed Histories, by Max Dashu.

#witch fashion#witch style#history of witches#chinese history#european history#east europe#witchblr#witchcraft#pagans#max dashu#witch hunts

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Primer for the Non-Subscriber: The Conical Hat

"You can choose a ready guide, in some celestial voice.

If you choose not to decide, you still have made a choice.

You can choose from phantom fears, and kindness that can kill.

I will choose a path that's clear, I will choose free will."

~Neil Peart

Let us delve into WHY “Black Hat Society” was chosen.

Come, take a walk with me through the words of history. Our first stop will be short, here is the “why” for color.

By definition, “black” is the absorption of ALL colors in the visible spectrum. The CONES in our eyes perceive this as “nothing” being reflected or refracted from something. All light is absorbed by that thing (Newton’s). This is perceived as a ONENESS to me. ALL things are absorbed because all things are as one. Furthermore, I do not subscribe to any preconceived notions or prejudices forced upon society over time. With that, I am neither a Theist nor Atheist. I believe there is a little #TRUTH in ALL THINGS. Even something that only exists in thought, “is”. That which is not perceived, or does not exist in thought, “is” too.

I digress. Let us talk more about the history of this millinery success. This hat has traveled through human existence for thousands of years. The conical black hat has carried with it meanings of power, both positive and negative. Most recently, a hat of this style (conical black felt) was discovered on mummies from around 4,000 years ago with the “Subeshi Witches”, found on the northern Silk Road trade route. (Although, we now understand that those around the World who were known as “witches” often did not even cover their heads or wore simple scarves instead.)

Before 1000 BC, also known as the Bronze Age, priests (because this title has ALWAYS referred to “elder” , “one with knowledge” or “wise one”) would wear golden conical hats that stood almost 3 feet tall. These hats were decorated with sun and moon symbols, indicating that their wearers were star-trackers who were able to analyze the sky to study celestial bodies and predict the weather. This is not such a mystery today. Seeing the power these people commanded from others around them by simply paying attention to their environment, dogma was taking notice.

Did the “Three Wise Men” derive from here? Was a conical hat worn to the birth of this particular messiah? They did follow a star after all.

None the less, their meteorological ability, misunderstood by many, caused the priests to be referred to as “king-priests” and were thought to have magical powers. It was also believed that they had access to a divine knowledge that enabled them to look into the future. Much of this was simply the ability to follow “cause and effect”. It is from this early use of conical hats that led to the traditional star-spangled wizard’s hat that we recognize in clothing today.

There was some thought of the Babylonian Jews at this time wearing conical hats themselves by choice. Possibly a conquered people from Iran? Scythian? Their warriors were described as wearing “conical hats” from cuneiform inscriptions found from that time. Regardless, they were forced to then wear them as a form of discrimination from the Islamic groups of Iraq. This “public identification” carried on for thousands of years for anyone connected to this hat.

Jump forward in time to the “Christ Era”.

In the 6th to 10th century, also referred to as The Dark Ages (the first half of the Middle Ages from 500 to 1000 AD) not a lot of history was able to be kept. This was a very volatile time during human existence. The Roman Empire fell and a lot of writings and knowledge were lost to the ages. The collapse of the Roman Empire lead to a lack of a kingdom or any political structure. This caused the churches of the time to take control and they became the most powerful institutions in Europe. It was during this time the Church began taking elements of “heathen” culture and Old Religion to appropriate for their agenda of conquer and expand.

Turning to the 11th century, the conical hat seemed to have been morphed into use as the Mitre, an accessory vestment, by the Church. There is quite a debate about this. You can observe from various timeless Brotherhoods of Xtianity, that the conical hat remained in use. The Spaniards are the main ones that held fast to this piece of attire. Intolerance and its representation of “wrongness” continued for the hat. It began being used for those serving “penance” with the Church.

The Practitioners who walked this Path were called Penitents. Traditionally in Spain, those wearing the conical hat were known as capirotes. It was used during the times of the Spanish Inquisition as a punishment. Bastardized as many things were from the histories of previous peoples, the condemned by that Tribunal were obliged to wear a yellow robe – saco bendito, also known as a blessed robe that covered their chest and back. along with the hat. The hat was a paper-made cone on their heads with different signs on it, alluding to the type of crime they had committed. For instance, those to be executed wore red. The were also green, white and black colors worn.

The Church’s power began to waiver again and they had to do “something” to bring it back to their grasp. One of their thinkers, whom I believe was connected to the Inquisition, began looking around for ways to do this. In 1214, The Dominican Order was established in the Catholic church. The first group on their radar was the Manicheans. For more than a thousand years, since the Roman Empire was in power, war with the Persian Empire (Middle East) which included the Manichaeans, carried on. The Manichaens were seen as representatives of a foreign power and as dangerous aliens, even though they were but a small section of Persia. Sound familiar?

The Mani had not been supporters of the Persian Empire's wars with other lands, including Rome, but that was overlooked. The Romans persecuted the Manichaeans, while Jews were also being persecuted. And without the backing of the brute power of a major state in the Middle East/Persia, Manichaeism would all but disappear in the future. They were considered “outcasts” in their own society. I wonder if they wore “conical hats”? Do you know who the Yazidi are? You should.

While this was happening, we move further into the 12th century with our hat. The Mongol Queens from the Mongol Empire founded by Genghis Khan in 1206, were wearing these conical hats too. Originating from the Mongol heartland in the Steppe of central Asia. By the late 13th century it spanned from the Pacific Ocean in the east to the Danube River and the shores of the Persian Gulf in the west. Khan’s was a competing empire for world dominance. None the less, there were no real differences in men and women’s clothing for the time but the Mongols needed to be seen from great distances, hence, the tall conical hat. This empire would not last against another… and the hat traveled.

As the story goes, Marco Polo brought back a sample of this hat to Europe in the 14th Century. The voracity of land grabs had already begun in the World. Mother Nature was being raped and disregarded and “fashion” became more important than meaning or purpose. The women of the time began wearing a conical hat called a hennin, not as Practitioners, but as fashionistas of their time. Very much unlike the willow-withe and felt Boqta (Ku-Ku) of Mongolian Queens. This appropriation became known as “the princess hat” and was worn tilted back on the head and veiled with brightly colored fabrics.

The “witch”, a word now derived from the Old English nouns wicca with an Old English pronunciation: [ˈwɪttʃɑ], meaning 'sorcerer, male witch, warlock' and wicce, the Old English pronunciation: [ˈwɪttʃe] for 'sorceress, female witch', actually becomes murky in meaning and language after this. The “witch” hunts were now well under way.

Since the beginning of its blighted past, the conical hat has stood to represent those outcast by their society. This seemed more prevalent in the later half its history. Why? The perpetuation of it being “negative” began with the Church.

It is of my opinion, the wearers of this hat were hold outs of Old Religion, Earth-Minded Folk and others at the turn of “the Christ event”. Because they did not or would not subscribe to what they were being sold, they became outcast from the forward momentum of society at that time. “Those in power”, i.e. Rome and later Europe and North America would not stand for anyone that did not conform to their forward march of greed and exploitation of Earth and “lesser humans”.

As we slipped into the 15th century, thousands were dying at the hands of those in power. The danger of witches became a widespread public concern. Urbanization and increased trade with foreign lands, along with epidemics of plague and cholera resulting from that trade, the onset of the Little Ice Age, upset feudal and religious hierarchies, ALL gave way to a convoluted mindset. “Something” had to be the cause. The was NO personal accountability. There was a widespread sense that the uncontrollable forces of change were destroying all order and moral tradition and the Church’s control. Persecuting witches redefined society’s moral boundaries and secured who was in control. This shift lent a leg up to allowing, and almost requiring, the demoralization of self if one did not conform or think or act like the majority in society. Differences in people, like those who were LGBTQ, although a part of us for thousands of years, were persecuted by the Church.

While we are passing through the 15th century, let us also consider the possibility that the witch’s hat is an exaggeration of the tall, conical “dunce’s hat” that was popular in the royal courts of the time as well. Or, let us consider the tall but blunt-topped hats worn by Puritans and the Welsh, who also had separate ideas than the majority. No matter what the fashion, pointed hats were frowned upon by the Church, which now associated points with the horns of the devil to maintain its power and fear-mongered agendas.

Let us also consider, somewhere along the way, an artist took creative license and added a brim to the timeless conical hat. Why would they do this?

Brimless, conical hats had long been associated with male wizards, magicians, Jews, Mani and many other societal outcasts. And, it was a male dominated society as the shift was happening. Goya even painted witches with such hats. It is possible that an artist added a brim to make the hats more appropriate for women (according to the fashion “rules” at the time) and to better fit this agenda of forward motion and subservience of others. One theory holds that the stereotypical witch’s hat came into being in Victorian times or around the turn of the century, in illustrations of childrens’ fairy tales. The tall, black, conical hat and the ugly crone became readily identifiable symbols of wickedness, to be feared by children. Hence, more fear-mongering was created in the name of control by the Church.

I do not feel I need to retell the rest of the history of the conical, now brimmed, black hat of the last 500 years. You should all be aware of the many “witch” trials by now. You have walked through history with me. You see where it comes from. You see why Georgia Black Hat Society has the Mission Statement it does. You see, my fellow Practitioner, why I take the stances that I do and want to hold to a belief of ONENESS of all things, just as my kindred folk of the previous thousands of years have done. Not war. Not greed. Not conquering my neighbors’ houses while wearing the now hijacked “black hat” of the social elite.

Harmony. Love. Unity.

THAT is what this all means to me.

More to come.

Blessings.

Reverend Richoz, RN

#georgia black hat society#national black hat society#conical hat history#black hat history#practitioner#witch

0 notes

Text

Aozora’s Liberationion Mod APK Unlocked

New Post has been published on http://apkmodclub.com/aozoras-liberationion-mod-apk-unlocked/

Aozora’s Liberationion Mod APK Unlocked

Aozora’s Liberationion Mod APK Unlocked Let’s play a 2D action RPG!

Shining Blade collaboration being carried out!

Popular character of RPG “Shining Blade” resonate in the mind

It appeared in Sokuribe! Collaboration story events held!

Avant-garde, rearguard all success! Kimero a combo in a brilliant operation!

Cooperation action RPG appeared!

[Part 1] ◆ attention operation system! ◆

Without a complex operation freely Ayatsureru the character, realize the intuitive operation!

You can activate a number of flashy skills with only a few buttons

Equipped with the “Skill Selector”!

[Part 2] ◆ Toe in the coffin in the air combo! ◆

By break the mighty boss monster, into the air combo!

Connect the combo in cooperation with the fellow, I stab at once todome!

[Part 3] ◆ role shines five occupational groups! ◆

Providing a five occupational groups to enable various play style!

Occupation of the features to take full advantage of, overlook the formidable enemy!

And light warrior: connecting the combo with abundant skills!

– Weight Warrior: Nagiharau a powerful blow and extensive!

· Sokoshi: protect fellow in defense of the iron-clad!

· Yugekishi: unleash a powerful blow from a distance!

· Subeshi: support the allies in the recovery and attack by magic!

[Part 4] ◆ multi in all success! ◆

Multiplayer for a united front with up to four people, essential team work!

Let psyched make a strategy in the sortie before the lobby!

[Part 5] ◆ of force by the gorgeous actors voice! ◆

Pray Shirai Yusuke Rie Kugimiya bamboo us Saina water rapids

Akio Otsuka Marina Inoue Sumire UESAKA Takehito Koyasu

Namikawa Kenta Miyake Sawashiro Tetsuya Kakihara Miyuki Daisuke

Kimura Subaru ※ random order

«Recommended for People! »

People ◆ likes fighting game in the non-portable game machine (fighting game)

The capture in cooperation with fellow ◇, people who like online games

◆ RPG likes people

◇ voice actor likes people

◆ Sega likes people

0 notes

Text

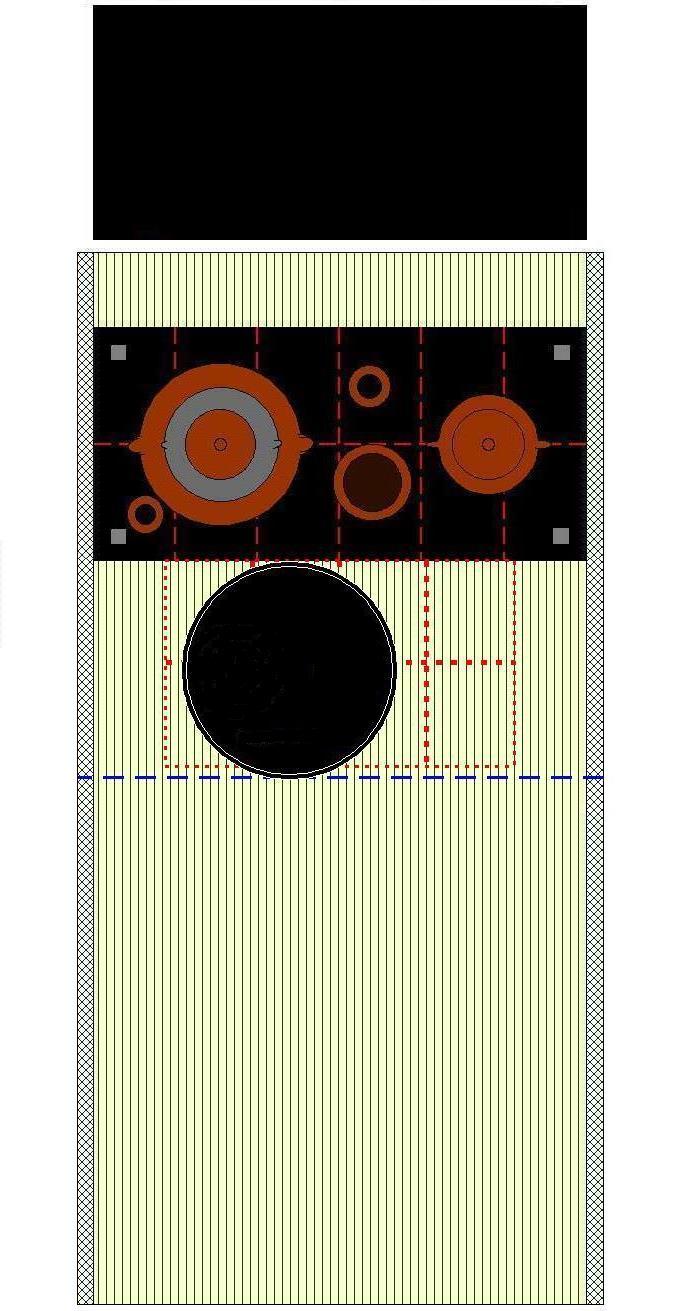

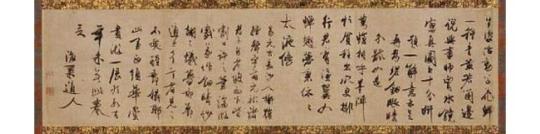

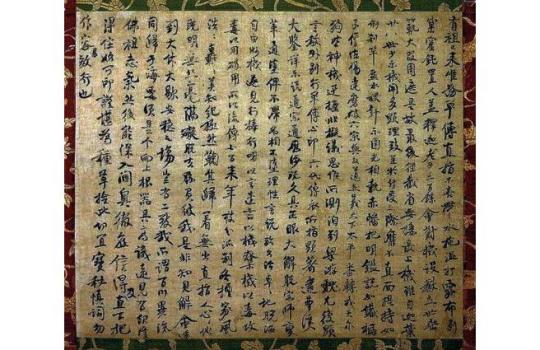

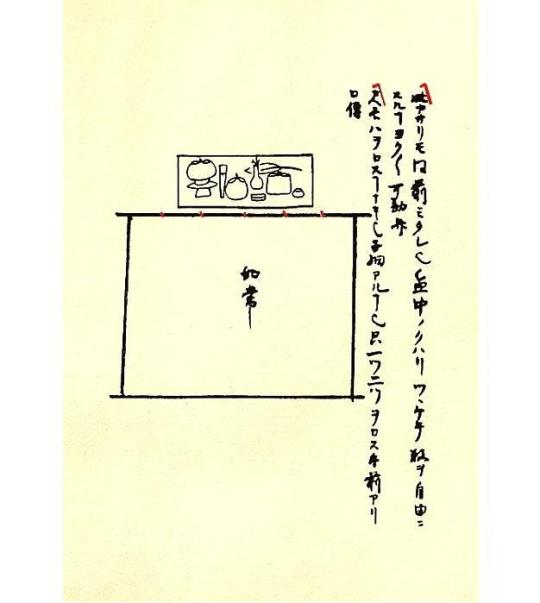

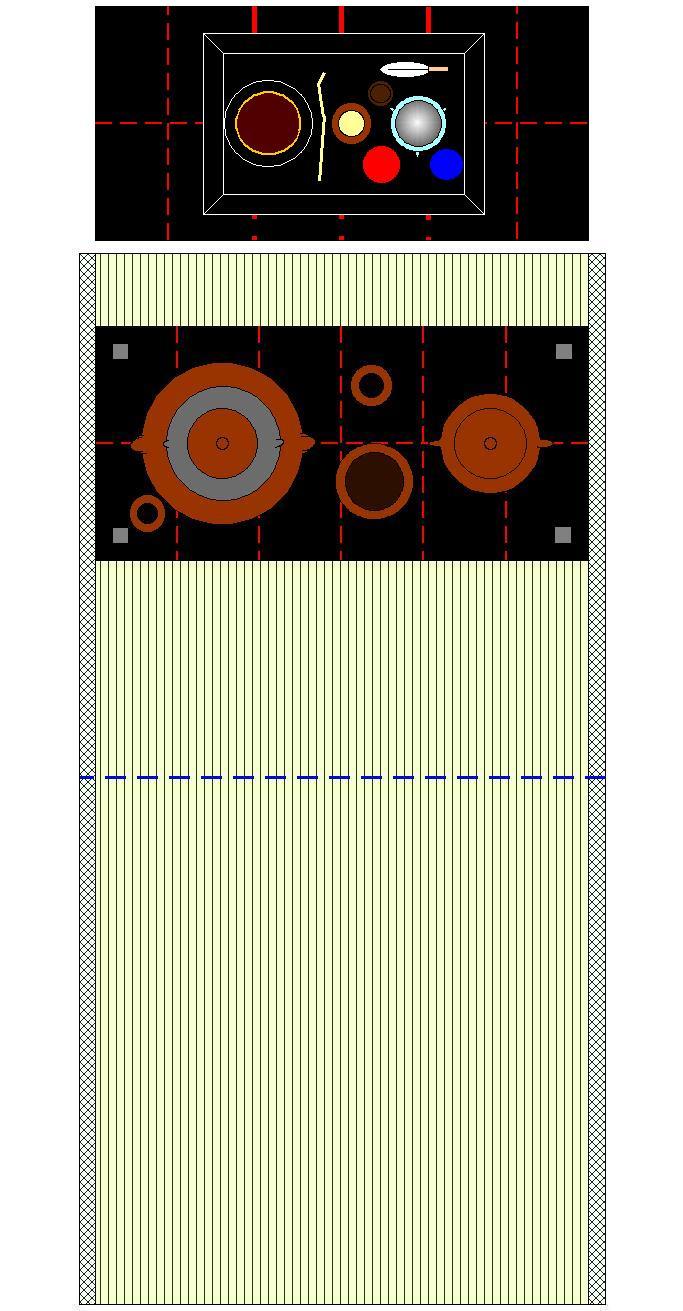

Nampō Roku, Book 7 (42, 43, 44): the Sketches for Entries 39, 40, and 41.

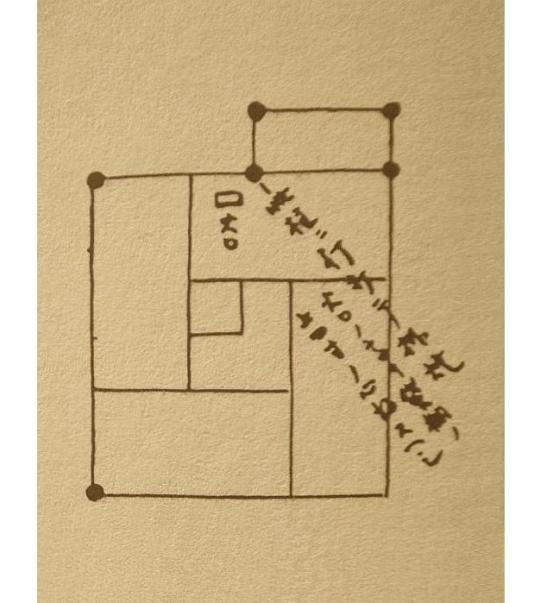

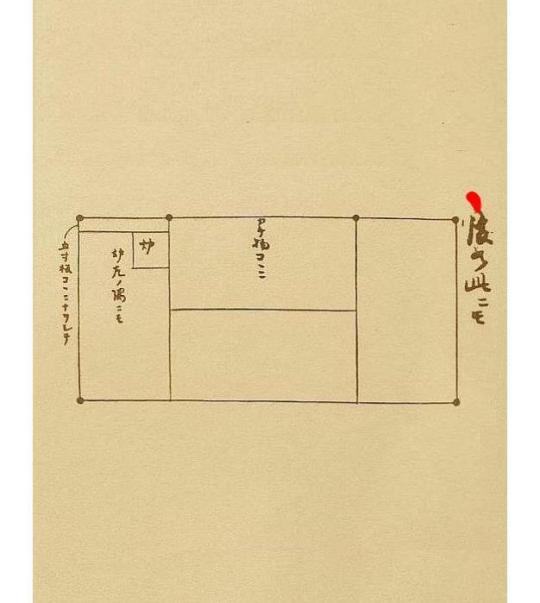

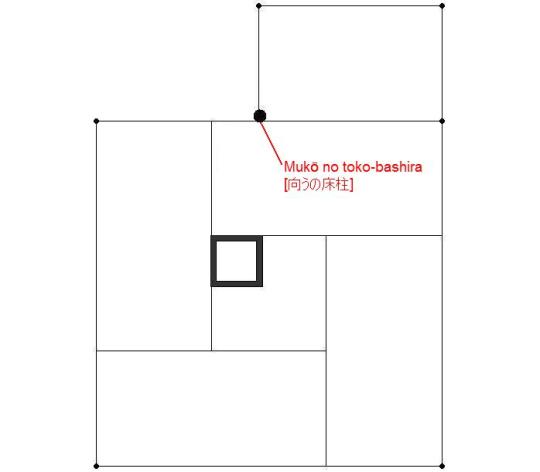

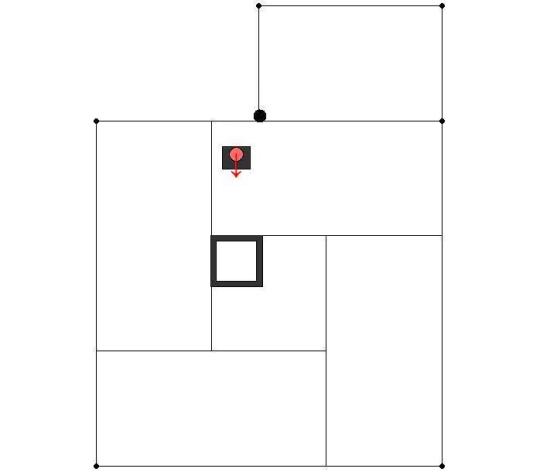

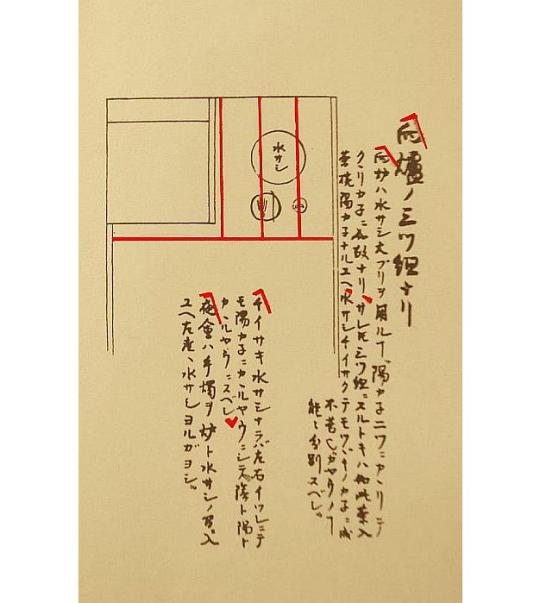

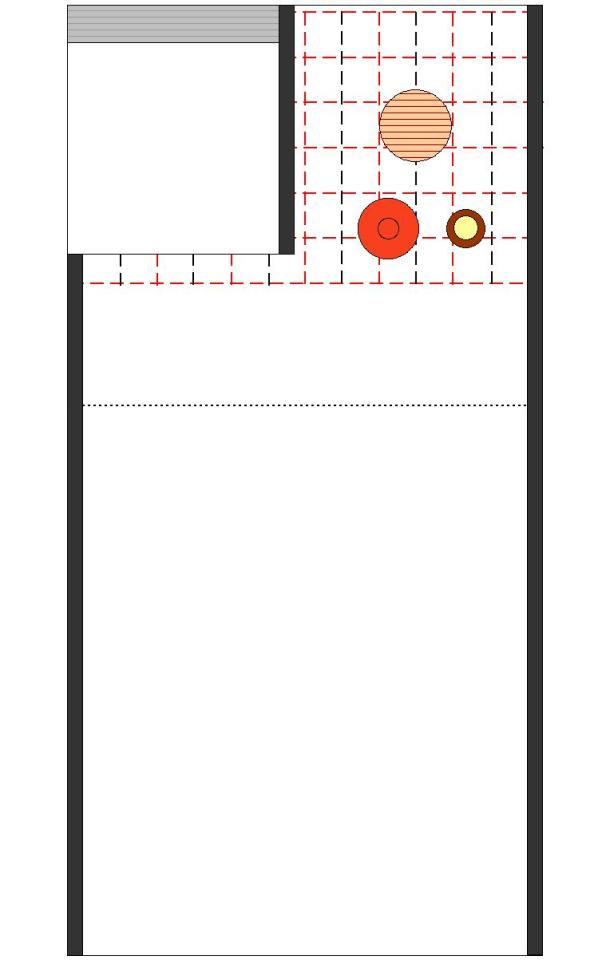

42) Yojō-han tomoshibi no oki-dokoro [四疊半ノ置所]¹.

[The writing reads: written on a diagonal, kono-hashira kugi-butsu kake-tomoshibi (此柱 釘打掛灯)², hi-guchi no takasa fukuro-dana no ue yon-sun no kokoro-e-subeshi (火口ノ高���袋棚ノ上四寸ノ心得スヘシ)³; center, hi-guchi (火口)⁴.]

〽 Go-shaku-toko no toki kaku-no-gotoki [五尺床ノ時如此]⁵.

〽 Tankei oki-kata yoshi, Shukō no shin-no-yojō-han, Engo no ō-haba wo kakerare-shi yue ikken-toko nari, tankei mo sono toki made ha okazu, shokudai nari, Jōō yojō-han, toko-naki mo ari, toko wo tsukerare-taru ha go-shaku nari [短檠置方ヨシ、珠光ノ眞ノ四疊半、圜悟ノ大幅ヲ掛ラレシ故一間床也、短檠モ其時マデハ不置、燭臺也、紹鷗ノ四疊半、床ナキモアリ、床ヲ付ラレタルハ五尺也]⁶.

[The writing reads: hi-guchi (火口)⁷.]

〽 Ikken-toko no toki, Sōkyū kaku-no-gotoki wo okaruru, Kyū ha tsu[w]i ni ji-ka ni te, sumi-kakete okare-taru wo mizu, aru-toki, Yodo-ya no yojō-han ikken-toko ni te ari-keru ni tōdai oki-taru ni, Kyū mi-tamaite, kore ni te koso aru-beki to no tamau, shikaraba sumi-kake ha konomarezu to oboe ni, Yodo-ya ha Kyū koni no montei nari [一間床ノ時、宗及如此ヲカルヽ、休ハツヰニ自家ニテ、スミカケテヲカレタルヲ見ズ、アル時、淀屋ノ四疊半一間床ニテ有ケルニ燈臺置タルニ、休見玉テ、コレニテコソアルベキトノ玉フ、シカレバスミカケハ不被好ト覺ニ、淀屋ハ休懇意ノ門弟也]⁸.

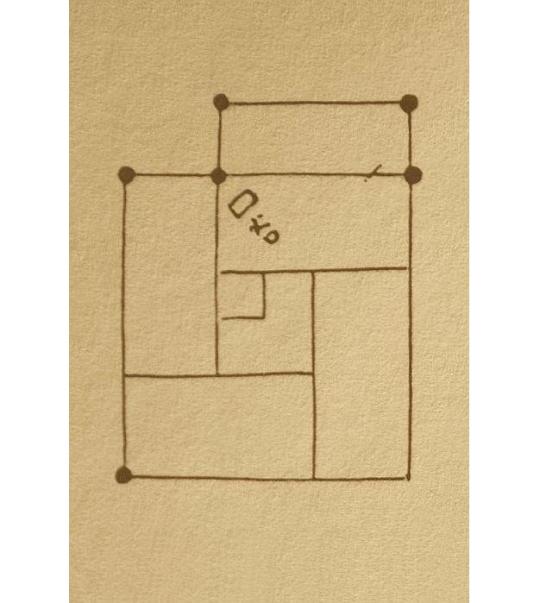

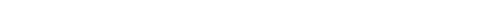

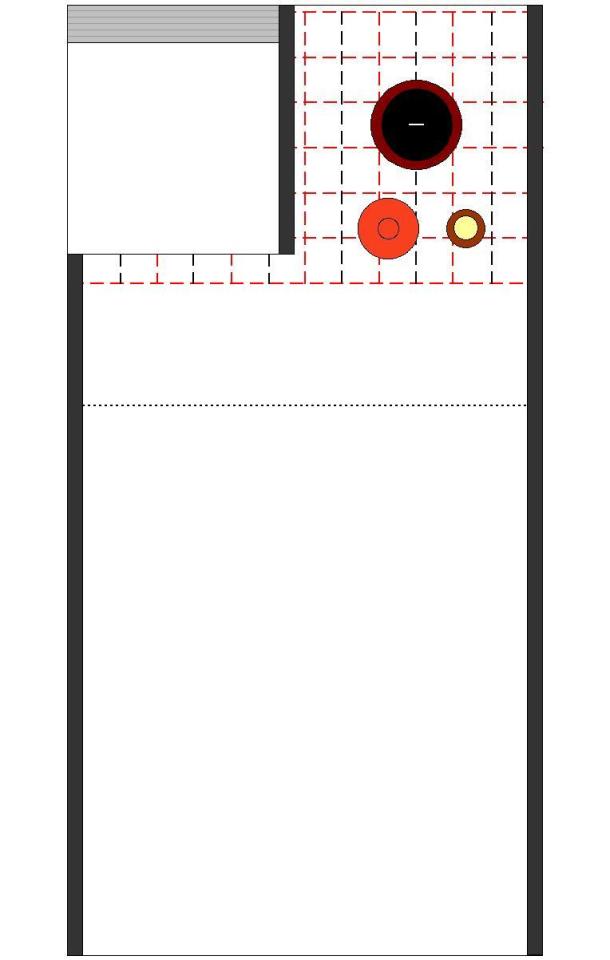

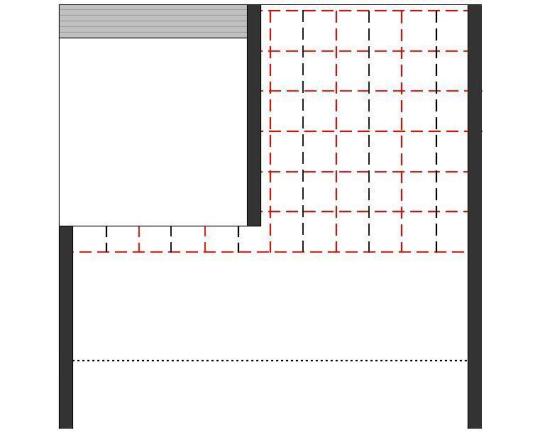

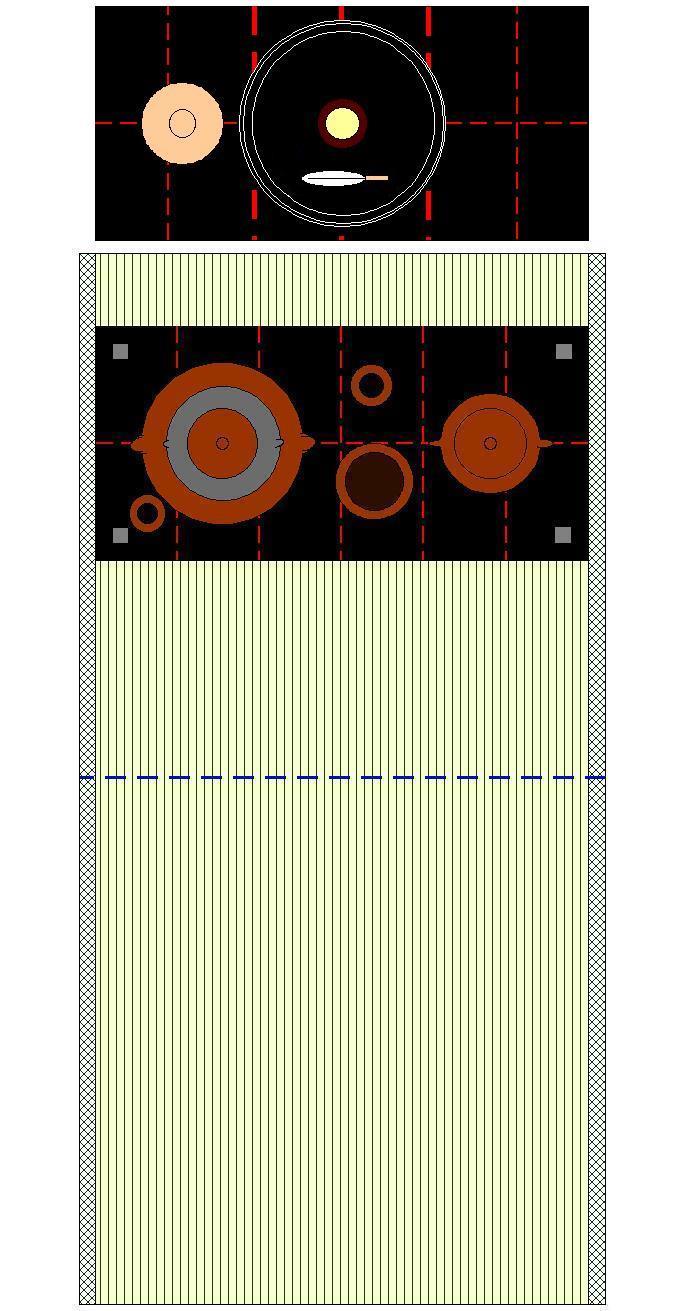

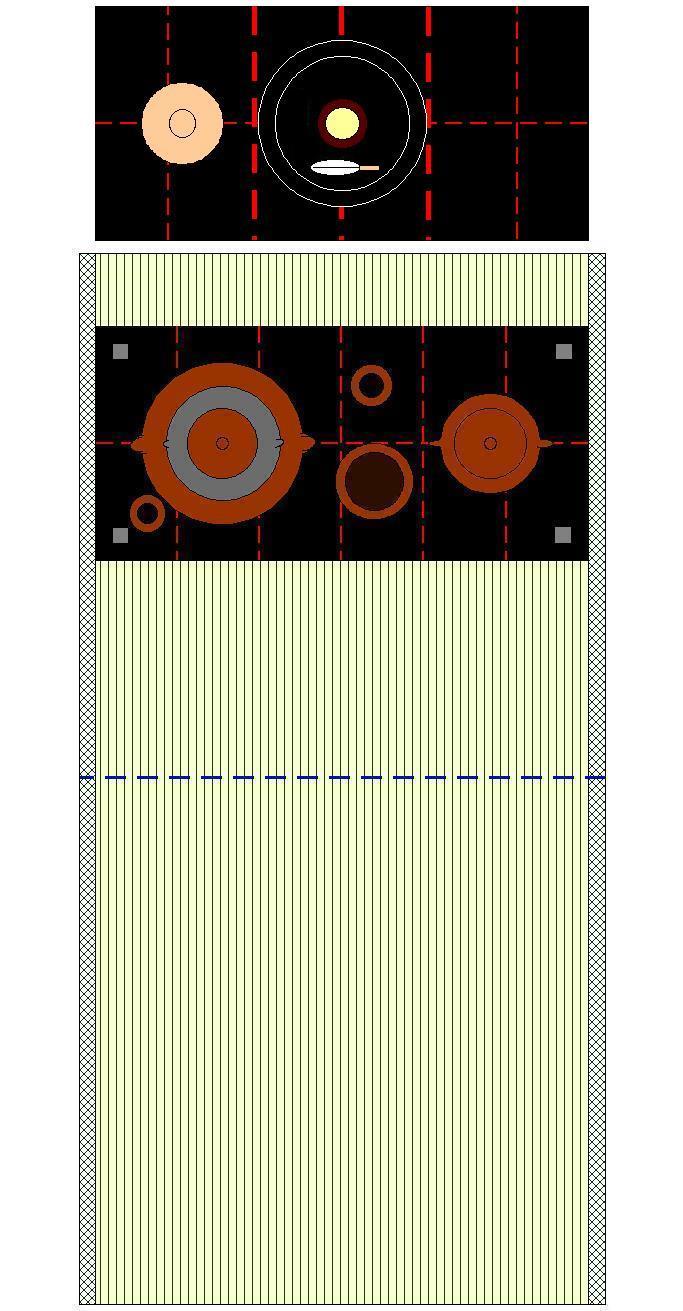

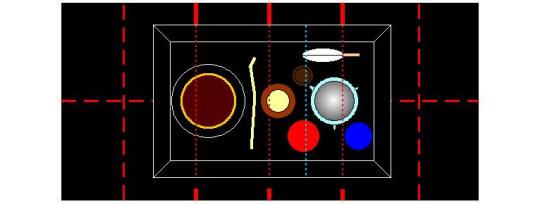

43.1) Fuka san-jō furu-zama [深三疊古様]⁹.

[The writing reads (right to left): kono tokoro kakemono (此所カケ物)¹⁰; kono kabe chū-dan kōshi ari, mata chū-dan made ni shite, hashira nashi ni, ita no furo-saki mo ari, takasa kama no mie-kakure (此カヘ中段カウシアリ、又中段迄ニシテ柱ナシニ、板ノ風爐サキモアリ、高サ釜ノ見ヘカクレ)¹¹; isshaku go-sun ita (一尺五寸板)¹²; ro wo koko ni kirareshi ha, isshaku-yon-sun kiwamarite ato no koto nari, hajime ha ita no ue ni daisu no gotoku, kane no furo mizusashi nado gu-shite oki-shi nari (爐ヲコヽニ切ラレシハ、一尺四寸キハマリテ後ノコト也、初ハ板ノ上ニ臺子ノコトク、カネノ風爐・水サシナト具シテヲキシナリ)¹³; kake-tomoshibi koko ni (カケ灯コヽニ)¹⁴.]

43.2) Ato kaku-no-gotoki ni mo [後如此ニモ]¹⁵.

[The writing reads: isshaku go-sun ita (一尺五寸板)¹⁶; ro (炉)¹⁷.]

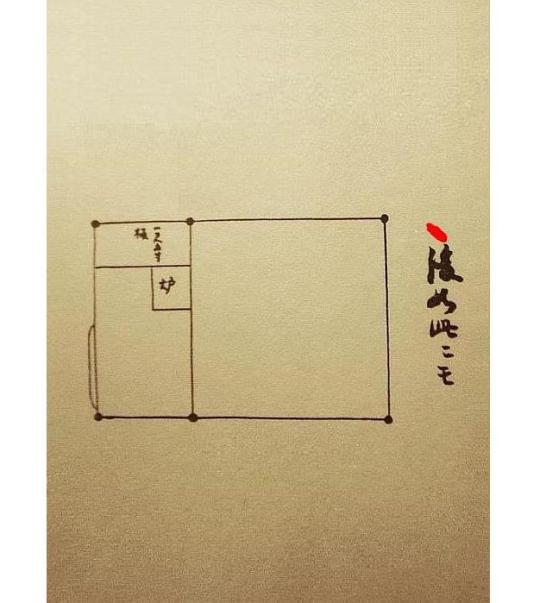

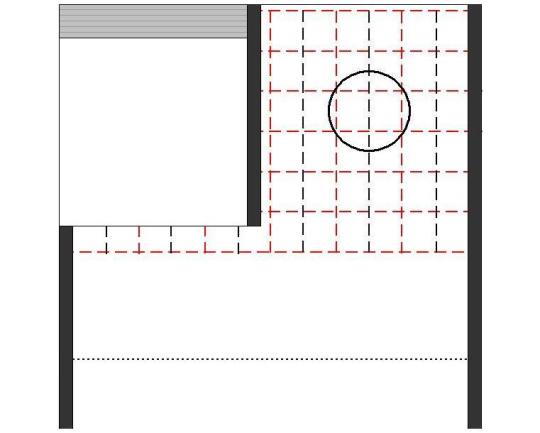

44.1) Naga-yojō furu-zama [長四疊古様]¹⁸.

[The writing reads, from right to left: kakemono koko ni (カケ物コヽニ)¹⁹; furosaki (風炉サキ)²⁰; go-sun ita (五寸板)²¹; ro (炉)²²; furo no toki kono ro no futa no ue ni oku-koto fuka-sanjō no i-fū nari (風炉ノ時コノ炉ノフタノ上ニヲク事深三疊ノ遺風也)²³, ro hidari no sumi ni mo kiru nari (炉左ノ隅ニモ切ル也)²⁴.]

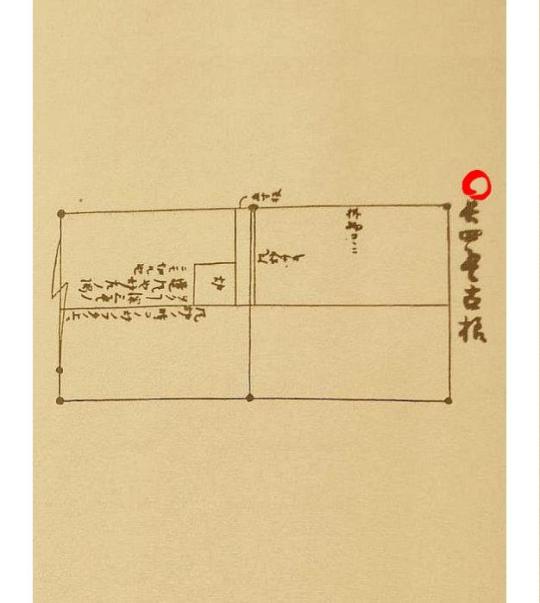

44.2) Ato kaku-no-gotoki ni mo [後如此ニモ]²⁵.

[The writing reads, from right to left: kakemono koko ni (カケ物コヽニ)²⁶; ro (炉)²⁷; ro hidari no sumi ni mo (炉左ノ隅ニモ)²⁸; go-sun-ita koko ni naoshite (五寸板コヽニホシテ)²⁹.]

_________________________

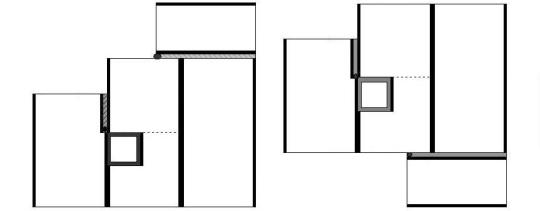

◎ This entry contains the six drawings that graphically memorialize the details of entries 39 (Lighting the 4.5-mat Room for the Shoza*), 40 (the Fuka-sanjō [深三疊] Room†), and 41 (the Naga-yojō [長四疊] Room‡). Even though these sketches have already been published in the posts to which they relate, I am repeating them here in order to maintain the series of entries as found in the Enkaku-ji manuscript version of Book Seven of the Nampō Roku.

In addition, I have included a translation of a related entry, from the Sumibiki no uchinuki-gaki・tsuika [墨引之内拔書・追加 ] (A Record of Excerpted Passages for Internal Use, Supplementary Material)**, that deals with certain points related to the three- and four-mat rooms, and their seating arrangements. This appears as an appendix, at the end of this post.

___________

*The URL for the post of entry 39 is:

https://chanoyu-to-wa.tumblr.com/post/702018933860040704/namp%C5%8D-roku-book-7-39-lighting-the-45-mat

† The URL for the post of entry 40 is:

https://chanoyu-to-wa.tumblr.com/post/702653075106742272/namp%C5%8D-roku-book-7-40-the-deep-three-mat

‡ The URL for the post of entry 41 is:

https://chanoyu-to-wa.tumblr.com/post/703015465673441280/namp%C5%8D-roku-book-7-41-the-long-four-mat-room%C2%B9

**In these translations, I usually refer to this pair of documents as the Book of Secret Teachings, and Second Book of Secret Teachings (the original Sumibiki no uchinuki-gaki only has 10 entries; most of the material that has drawn our attention is found in the much more expansive supplementary book, which contains 54 entries) for the sake of simplicity.

■ The translations found in footnotes 1 to 29 are pretty perfunctory, since everything has been discussed, in detail, in the posts (the URLs of which are given above) where these drawings first appeared. I have only provided explanations where circumstances seemed to make this appropriate.

¹Yojō-han tomoshibi no oki-dokoro [四疊半ノ置所].

This means the place to put the lamp in the 4.5-mat room.

²Kono-hashira kugi-butsu kake-tomoshibi [此柱 釘打掛灯].

“[If] a hook has been nailed into this pillar, a hanging lamp [may be hung here].”

³Hi-guchi no takasa fukuro-dana no ue yon-sun no kokoro-e-subeshi [火口ノ高サ袋棚ノ上四寸ノ心得スヘシ].

“Regarding the height of the hi-guchi, you should understand that it should be 4-sun above the fukuro-dana.”

⁴Hi-guchi [火口].

Hi-guchi refers to the place where the wicks extend above the rim of the lamp; the place where the flame is burning. The meaning here is that the hi-guchi should face toward the ro.

⁵Go-shaku-toko no toki kaku-no-gotoki [五尺床ノ時如此].

“When [the room has] a 5-shaku toko, it is like this.”

In other words, the drawing illustrates the arrangement in a room that has a 5-shaku toko.

⁶Tankei oki-kata yoshi, Shukō no shin-no-yojō-han, Engo no ō-haba wo kakerare-shi yue ikken-toko nari, tankei mo sono toki made ha okazu, shokudai nari, Jōō yojō-han, toko-naki mo ari, toko wo tsukerare-taru ha go-shaku nari [短檠置方ヨシ、珠光ノ眞ノ四疊半、圜悟ノ大幅ヲ掛ラレシ故一間床也、短檠モ其時マデハ不置、燭臺也、紹鷗ノ四疊半、床ナキモアリ、床ヲ付ラレタルハ五尺也].

“The way the tankei has been placed is suitable. In Shukō's shin [眞] 4.5-mat room, because he wanted to hang the wide scroll [that had been written by] Engo, [the room] had a 1-ken toko. Up to that time, the tankei was still not placed [in the tearoom]; [they] used a candlestick.

“Jōō also had a 4.5-mat room that did not have a toko. And when he wanted to attach a toko, it was 5-shaku [wide].”

⁷Hi-guchi [火口].

Again, the word hi-guchi indicates the orientation of the tankei. In this case, it is placed on a diagonal, so that the lamp gives light not only to the ro, but to the interior of the toko as well.

⁸Ikken-toko no toki, Sōkyū kaku-no-gotoki wo okaruru, Kyū ha tsu[w]i ni ji-ka ni te, sumi-kakete okare-taru wo mizu, aru-toki, Yodo-ya no yojō-han ikken-toko ni te ari-keru ni tōdai oki-taru ni, Kyū mi-tamaite, kore ni te koso aru-beki to no tamau, shikaraba sumi-kake ha konomarezu to oboe ni, Yodo-ya ha Kyū koni no montei nari [一間床ノ時、宗及如此ヲカルヽ、休ハツヰニ自家ニテ、スミカケテヲカレタルヲ見ズ、アル時、淀屋ノ四疊半一間床ニテ有ケルニ燈臺置タルニ、休見玉テ、コレニテコソアルベキトノ玉フ、シカレバスミカケハ不被好ト覺ニ、淀屋ハ休懇意ノ門弟也].

“When [the room] had a 1-ken toko, Sōkyū wanted to place [the tankei] like this. But [as for] Rikyū, [the tankei] was never seen to be placed so that it rested in the corner [of the mat] in his own home.

“On one occasion, in Yodo-ya’s 4.5-mat room with a 1-ken toko, the tōdai was placed out in the aforementioned way. When [Ri]kyū saw it, he declared ‘this is exactly the way it should be done!’

“In light of this, perhaps we should consider that he did not [really] like [the way Sōkyū had arranged it]. Yodo-ya [Gentō] was one of [Ri]kyū’s most intimate disciples.”

⁹Fuka san-jō furu-zama [深三疊古様].

“The old style of the deep 3-mat [room].”

¹⁰Kono tokoro kakemono [此所カケ物].

“The kakemono is [hung] in this place.”

¹¹Kono kabe chū-dan kōshi ari, mata chū-dan made ni shite, hashira nashi ni, ita no furo-saki mo ari, takasa kama no mie-kakure [此カヘ中段カウシアリ、又中段迄ニシテ柱ナシニ、板ノ風爐サキモアリ、高サ釜ノ見ヘカクレ].

“In the middle of this wall is a lattice-work. But again, with respect to this, including the making of [the lattice in] the middle, when the pillars [that would support the wall] are absent, a furosaki made from boards can also be [used].

“It should be high enough to hide the kama from view.”

¹²Isshaku go-sun ita [一尺五寸板].

“The board [measures] 1-shaku 5-sun.”

¹³Ro wo koko ni kirareshi ha, isshaku-yon-sun kiwamarite ato no koto nari, hajime ha ita no ue ni daisu no gotoku, kane no furo mizusashi nado gu-shite oki-shi nari [爐ヲコヽニ切ラレシハ、一尺四寸キハマリテ後ノコト也、初ハ板ノ上ニ臺子ノコトク、カネノ風爐・水サシナト具シテヲキシナリ].

“As for wanting to cut the ro here, this only appeared after the ro was fixed at 1-shaku 4-sun [square].

“Originally, a metal furo, mizusashi, and so on, were [all] placed on top of the board, just like [on] the daisu.”

¹⁴Kake-tomoshibi koko ni [カケ灯コヽニ].

“A hanging lamp is [suspended] here.”

¹⁵Ato kaku-no-gotoki ni mo [後如此ニモ].

“After, [the fuka-sanjō room] was also [arranged] like this.”

¹⁶Isshaku go-sun ita [一尺五寸板].

“The board [measures] 1-shaku 5-sun.”

¹⁷Ro [炉].

The ro is shown on the right. However, it was also permissible to cut it on the left side of the mat, adjoining the wall of the katte.

¹⁸Naga-yojō furu-zama [長四疊古様].

“The old style of the long 4-mat [room].”

¹⁹Kakemono koko ni [カケ物コヽニ].

“The kakemono is [hung] here.”

²⁰Furosaki [風炉サキ].

This furosaki could refer either to a free-standing screen made of two boards, or to one (or more) boards suspended between a pair of pillars. In either case, the height should be equal to that of the lid of the kama (when arranged on the furo).

²¹Go-sun ita [五寸板].

“The board [measures] 5-sun [wide].”

²²Ro [炉].

The ro is shown as being cut on the right side of the mat. While this was the orthodox position (according to the classical understanding that the fire should always be located between the part of the room where the guests were seated, and the mizusashi and chaire), it was also permitted for the ro to be cut on the left side (which corresponded with its position on the ji-ita of the daisu).

²³Furo no toki kono ro no futa no ue ni oku-koto fuka-sanjō no i-fū nari [風炉ノ時コノ炉ノフタノ上ニヲク事深三疊ノ遺風也].

“When the furo is being used, there is the case where it is placed on top of this lid of the ro. This was a practice of long standing that began with the fuka-sanjō.”

²⁴Ro hidari no sumi ni mo kiru nari [炉左ノ隅ニモ切ル也].

“The ro may also be cut in the left corner [of the mat, in front of the board].”

²⁵Ato kaku-no-gotoki ni mo [後如此ニモ].

“After, [the naga-yojō room] was also [arranged] like this.”

²⁶Kakemono koko ni [カケ物コヽニ].

“The kakemono is [hung] here.”

²⁷Ro [炉].

This was the more common location for the ro [based on the argument that the fire should be moved closer to the guests when the weather was cold].

²⁸Ro hidari no sumi ni mo [炉左ノ隅ニモ].

“The ro may also be [cut] in the left corner [of the utensil mat].”

²⁹Go-sun-ita koko ni naoshite [五寸板コヽニホシテ].

“The go-sun-ita is repositioned here.”

“Repositioned” (naoshite [直して]) because, in the original form of the room, the board appeared to be oriented between the utensil mat and the mat that was functioning as the tokonoma. According to that idea, the board should have been found on the right side of the mat. However, that is mistaken. The board should be found at the end of the utensil mat, to make it seem to be an inakama-datami.

==============================================

❖ Appendix: Entry 39 from the Second Book of Secret Teachings.

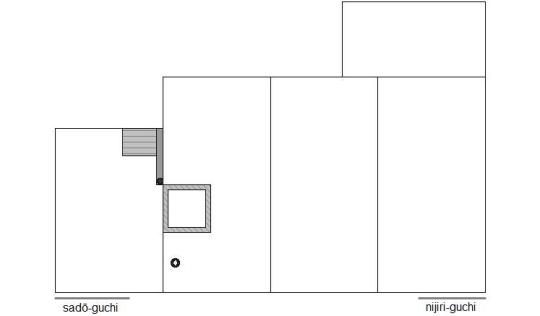

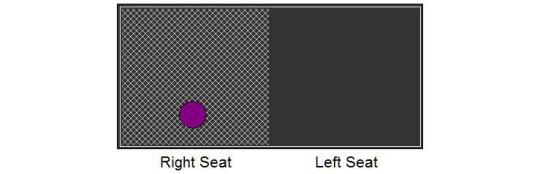

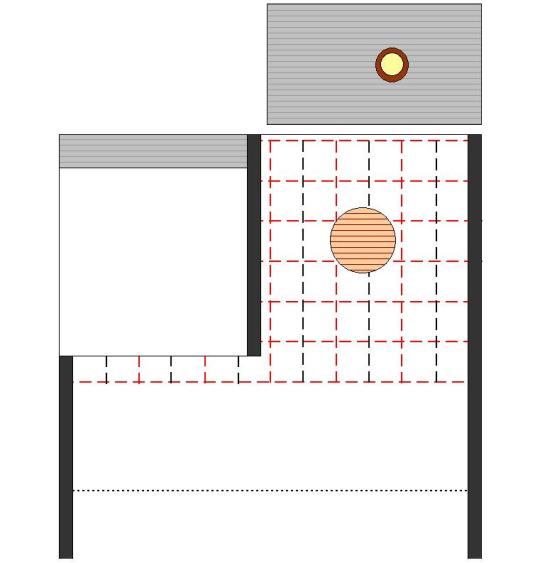

Because the deep 3-mat room was originally [just] the [enclosed] veranda of Jōō's sitting room, there was only one way [for the guests] to advance [through the room]³⁰. Later this [problem] was resolved [by changing the orientation of the mats]; but even if this gave [the guests] more freedom [to move about]³¹, it did not really solve [the problem]³². As a result, in the present day [the three-mat room] has largely been discarded³³.

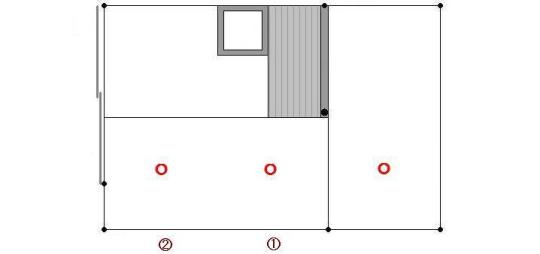

० The deep three-mat room:

〽 (①) If the shōkyaku [takes his seat] here, his position will be the same as when the room has an ordinary mukō-ro³⁴.

〽 (②) If [the guests] take their seats as shown [in this drawing, with the shōkyaku seated in the spot indicated near the katte-guchi], the host will have appropriate access [to all of them]³⁵.

〽 If, during the furo season, [the utensils are arranged] only on the board, [the host] will not be able to gain access to [all of the guests]³⁶.

〽 In any case, it is appropriate for the shōkyaku to sit near the katte-guchi (as shown in this sketch), during both the sho[za], and the go[za]³⁷.

० The long four-mat room:

〽 When the host is serving the guests, there is no way for [him] to gain access to the [guest in the] last seat³⁸. Consequently, the shōkyaku should undertake to act as his intermediary, passing things along to the [person in the] last seat³⁹ -- because, otherwise, there will be no way for the host to be able to serve [that guest]⁴⁰.

[A guest who understands] such [things] is what we mean when we say that a “man of experience” enters [the tearoom]⁴¹.

_________________________

³⁰Fuka-sanjō ha Jōō i-ma no engawa naru yue, ippō agari nari [深三疊ハ紹鷗居間ノ椽カハナル故、一方アカリナリ].

Jōō i-ma no engawa [紹鷗居間の縁側]: i-ma [居間] means a living room, a residential room, or a sitting room (a room that could be used to receive guests); engawa [椽カハ = 縁側] usually means a porch or veranda, but here it seems to refer to a sort of room created by arranging mats on a veranda, which are then enclosed by banks of shōji along the exposed sides to protect them from the weather*. This space was then used as a dedicated tearoom.

Fuka-sanjō ha Jōō i-ma no engawa naru yue [深三疊は紹鷗居間の縁側なるゆえ] means “because the deep 3-mat room was originally (just) the (enclosed) veranda of Jōō's sitting room....”

Ippō agari nari [一方上がりなり] means something like “there was only one way to advance (into the room).”

In other words, due to the limited space available on the preexisting veranda, the area of the mats available for the guests to enter were limited to a single line. Thus, there would be no room for two-way traffic. Once a person moved to the end of this line of mats, and he was followed by others, he could not get out again unless the other guests left the room first.

__________

*However, according to Kotobank [コトバンク] https://kotobank.jp/, this kind of enclosed veranda only appeared during the first half of the seventeenth century (jū-shichi seiki zenhan ni fuki hanashi no irigawaen kara naibu ni torikoma reta engawa ni henka shite iru [17世紀前半に吹き放しの入側縁から内部に取り込まれた縁側に変化している]). This would make the argument that Jōō purportedly enclosed his veranda to create this kind of room an anachronism -- a concept possibly generated by the machi-shū to give historical legitimacy their 3- and 4-mat rooms.

³¹Ato ni naoshite jiyū ni shitaru jūkyo mo aredomo [後ニナホシテ自由ニシタル住居モアレドモ].

Ato ni naoshite [後に直して] means later this (problem) was resolved (by changing the orientation of the mats so that the utensil mat was perpendicular to the two mats on which the guests would sit).

Jiyū ni shitaru jūkyo mo aredomo [自由にしたる住居もあれども] means even if (this) were done so that (the guests) would be free (to move about as they wished)....

³²Jū-bun naki yue [十分ニナキユヱ].

Ju-bun ni nai yue [十分にないゆえ] means this was not enough.

In other words, while rearranging the room and so give the guests free reign to move around the two mat area was an improvement over the original form of the three-mat room, it still meant that, regardless of how the mats were arranged, one of the guests would still be sitting within the same one-mat space as the kakemono. Thus, this was not ideal.

Apparently, the argument that is being made is that, because this 3-mat area was being appended to the outward-facing side of Jōō's preexisting 4.5-mat reception room, he was thereby limited with regard to the length of the room -- which could not exceed the width of the room to which it was attached (namely 9-shaku 4-sun 5-bu, or a mat and a half).

³³Tō-sei chari-tari [當世捨リタリ].

Tō-sei [當世] means in the present day (i.e., the early Edo period, when this text was written).

Shari-tari [捨りたり]: shari [捨り = 捨離] means to abandon (specifically, all worldly desires), so here shari-tari seems to be roughly equivalent to sute-tari [捨てたり], and so means that the three-mat room had largely been relegated to the dustbin of history by the time this text was written. It was no longer used, because it could not fully free itself from the danger of inconveniencing the guests.

³⁴Koko ni shōkyaku tsugi-taraba tsune no mukō-ro no mi-gamae [コヽニ上客ツキタラバ常ノ向炉ノ身構].

Tsugi-taraba [次たらば] means to want to sit beside, will sit beside.

In other words, if the shōkyaku decides to sit in that place*, everything will be done as if they were in a 2-mat room with a mukō-ro.

__________

*This seems to mean that the shōkyaku enters the room last (so that he will take his “rightful” seat in front of the toko). Then, after he has finished inspecting the toko, he moves onto the next mat (so that the other two guests will have to move closer to the lower end, so that all three are sitting on the same mat).

³⁵Kaku-no-gotoki za-tsuki-sōraeba shu no mi-gamae hirakite yoshi [如此座着候得バ主ノ身構ヒラキテヨシ].

Kaku-no-gotoki za-tsuki-sōraeba [かくの如き座着き候えば] means if the guests all take their seats as shown (in the drawing)....

Shu no mi-gamae hirakite yoshi [主の身構開きてよし ] means that the host will have suitable access (to all of the guests); the host will be able to serve them appropriately.

³⁶Ita bakari ni te furo no toki ha hiraku-koto nashi [板斗ニテ風炉ノ時ハヒラクコトナシ].

Ita bakari ni te furo no toki [板ばかりにて風炉の時] means when, during the season of the furo, (all of the utensils) are (arranged only) on the mukō-ita [向板]*....

Hiraku-koto nashi [開くこと無し] means (the host) will not have access (to all of the guests).

This is because, when the utensils will be arranged on the board, not only are the furo and kama placed out during the shoza, but also the mizusashi, shaku-tate, koboshi, and futaoki -- just as if these things were arranged together on the o-chanoyu-dana (from which this arrangement was actually derived). As a result, the host will be unable to pass as close to the board as he could when there was nothing on it.

__________

*The large board measuring 3-shaku 1-sun 5-bu by 1-shaku 5-sun.

³⁷Shōkyaku to-kaku katte-guchi no kata ni zu no gotoku sho-go tomo ni ite yoshi [上客トカク勝手口ノ方ニ図ノコトク初後トモニ居テヨシ].

Tokaku [とかく] means anyways, in any case, at any rate.

Katte-guchi no kata ni [勝手口の方に] means in the place closest to the katte-guchi.

Zu no gotoku [図の如く] means as is show in the sketch.

Sho-go tomo ni [初後ともに] means during both the shoza and (also) the goza.

Ite yoshi [居てよし] means it is appropriate to remain (in that seat).

³⁸Shu tamai-suru toki ha matsu-za made tōru-beki michi nashi [主給スル時ハ末座マデ通ルベキ道ナシ].

Shu tamai-suru toki [主給いする時] means when the host is serving the guests -- the reference is to his serving of the kaiseki (and specifically to things like handing each guest his own tray of food, pouring sake for each of the guests, and so forth).

Matsu-za made tōrubeki michi nashi [末座まで通るべき道なし] means there is no path for (the host) to gain access to the (guest in the) last seat.

³⁹Shōkyaku tori-tsukite matsu-za [h]e yaru nari [上客取次テ末座ヘヤルナリ].

Shōkyaku tori-tsukite [上客取り次ぎて] means the shōkyaku (should) act as an intermediary; the shokyaku should pass (that thing) along.

Matsu-za [h]e yaru [末座へ遣る] means pass (it) along to (the person in) the last seat.

In other words, with respect to something like the tray of food, the shōkyaku should receive it from the host and then pass it over to the last guest; and as for the pouring of sake, the shōkyaku should request the chōshi [銚子] or tokuri [徳利] from the host, and then pour for the last guest.

⁴⁰Sa nakereba shōkyaku [h]e shu no kyuji-jika ni watasu-koto narazaru-koto nari [サナケレバ上客ヘ主ノ給仕直ニ渡スコトナラザルコトナリ].

Sa nakereba [さなければ] means otherwise.

Shōkyaku [h]e shu no kyuji-jika ni watasu-koto narazaru-koto [上客へ主の給仕直に渡すことならざること] means if the host does not pass this task over to the shōkyaku, the host will be unable to serve (the last guest).

⁴¹Kōsha no iru to iu ha kayō no koto nari [功者ノ入ルト云フハカヤウノコトナリ].

Kōsha no iru to iu ha [功者の入ると云うは] means when we speak about a man of experience entering (the tearoom)....

Kayō no koto nari [斯様のことなり] means that is what we are talking about.

0 notes

Text

Nampō Roku, Book 7 (39): Lighting the 4.5-mat Room for the Shoza.

39) In the 4.5-mat room, the small shokudai [小燭臺], and also the Genji-tomoshibi [源氏火], may [both] be used¹. [And] since [the days of] Jōō, the tankei [短檠] has also been used².

[If] a hook has been nailed into the toko-bashira that faces [the ro], it is also acceptable to use a kake-tomoshibi [掛燈]³.〚But because [the kake-tomoshibi] is rather inelegant, with things like the kyū-dai [及臺 = kyū-dai daisu, 及第臺子] or naka-ita [中板 = the modern nagaita, 長板], [we should] always [use] a shokudai [燭臺], or possibly a Genji-tōdai [源氏燈臺] -- though there is also nothing wrong with using a tankei [with tana of this sort]⁴.

〚[When using] a kake-tomoshibi, [you] should consider [what will be] the [most appropriate] height for the flame when hanging [the lamp]⁵:〛as for its height, when the fukuro-dana has been placed [on the utensil mat], the flame should [be high enough to] illuminate the utensils on the upper level [of the tana]⁶.

When the toko is 1-ken wide, the way to place the tankei -- and [the way to orient] the hi-guchi [火口] as well -- is for it to be put into the corner [oriented diagonally]. [Tennōji-ya] Sōkyū first started placing it in this way, and [Ri]kyū also said it should be [like that]⁷.

(However, perhaps [Rikyū] was not in complete agreement with [Sōkyū’s way of doing things]⁸?)

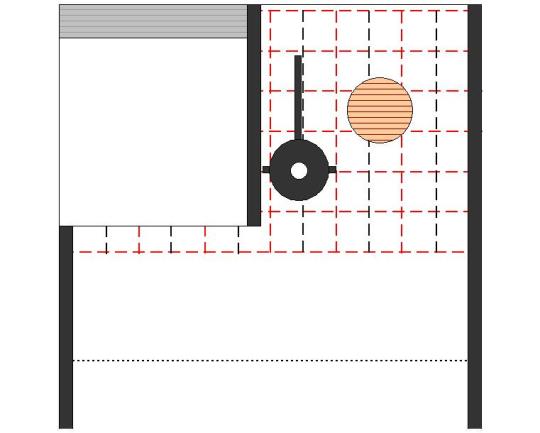

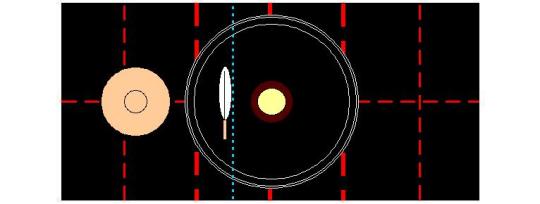

○ The place to put the lamp in the 4.5-mat room⁹.

[The writing reads: written on a diagonal, kono-hashira kugi-butsu kake-tomoshibi (此柱 釘打掛灯)¹⁰, hi-guchi no takasa fukuro-dana no ue yon-sun no kokoro-e-subeshi (火口ノ高サ袋棚ノ上四寸ノ心得スヘシ)¹¹; center, hi-guchi (火口)¹².]

〽 When [the room has] a 5-shaku toko, [things] are like this¹³.

〽 The placement of the tankei [should be] suitable¹⁴. Because Shukō intended to hang the large scroll [by] Engo in his shin [眞] 4.5-mat room, it had a 1-ken toko¹⁵. But, at that time, the tankei was as of yet not placed [in the tearoom]¹⁶: [they used] a shokudai¹⁷.

Jōō also had a 4.5-mat room that did not have a toko¹⁸; but when [he] was going to attach a toko [to his tearoom], it was 5-shaku [wide]¹⁹.

[The writing reads: hi-guchi (火口)²⁰.]

〽 When [the tearoom had] a 1-ken toko, Sōkyū placed [the tankei] like this²¹. [But] as for Rikyū, [the tankei] was never seen to be placed as if he wanted it to rest in the corner [of the mat] in his own home²².

On a certain occasion, in Yodo-ya [Gentō’s] 4.5-mat room -- which had a 1-ken toko -- the aforementioned tōdai was placed out〚but it was not oriented [diagonally] from the corner²³.〛 When [Ri]kyū inspected it, he declared “this is just the way it should be done!” In light of this, perhaps we should consider that he did not [really] like [the way Sōkyū had arranged it]²⁵.

Yodo-ya [Gentō] was one of [Ri]kyū’s most intimate disciples²⁶.

_________________________

◎ This entry deals with the way to orient the light-source in a 4.5-mat room during the shoza* (when it is important for the light from the lamp to fall into the ro, so the host can see what he is doing when he performs the sumi-temae). The language of the latter half is very unusual, and consequently difficult -- suggesting that someone very different from the usual “contributors” was responsible for editing what may have been originally an actual entry by Nambō Sōkei†.

Shibayama Fugen’s teihon contains several additions; and this added content is largely confirmed by material quoted by Tanaka Senshō in his commentary‡. As these additions certainly make the explanation clearer (even if some of the assertions might also be misleading)**, I decided to include Shibayama’s additions in the above translation -- enclosed in doubled brackets, as always.

Following Shibayama’s lead, I have also moved the two drawings, and their attending kaki-ire, into this entry (from their place several entries later in Book Seven, where they are really no good to anyone). This material begins with the title The place to put the lamp in the 4.5-mat room.

___________

*During the naka-dachi, the light was usually moved into the toko. However, during the shoza, the lamp-stand (of whatever description) was placed on the floor of the room (or, in the case of a lamp that was suspended on the toko-bashira, oriented with the lamp’s hi-guchi facing toward the utensil mat), since it was important that its light fall into the ro, so the host could see what he was doing while attending to the charcoal.

†The basic story of Rikyū adopting Tennōji-ya Sōkyū’s suggestion, regarding the way to orient the tankei in a 4.5-mat room with a 1-ken tokonoma (in other words, the material that was included in the Enkaku-ji manuscript) seems to be authentic – because it is historically in character (even though this disagrees with the Sen family’s myth of Rikyū being the all-knowing tea kami by whom all the rules were established). But his later doubts (indicated by a short gloss at the very end of the text), and the way Sōkyū’s idea is finally discarded, were obviously added later (since most of it is contained in several kaki-ire that inexplicably appear several entries later in Book Seven) -- this was probably an effort to make Rikyū’s ultimate behavior end up validating the Sen family’s preferred way of doing things, at least as they were teaching at that time.

‡Tanaka’s “genpon” text basically parallels Shibayama’s from footnotes 1 to 7 (albeit with a few minor changes that do not really have an impact on the meaning). The text breaks there, and resumes the story at footnote 13; but at this point it diverges from the other by giving a sort of summary of the things that are set down in more detail in Shibayama’s version. After which that text ends rather abruptly with the comment that these things are documented in the sketch(es) -- which accompany the kaki-ire later in Book Seven.

Given the degree of difference from Shibayama in that one specific instance, I will discuss Tanaka’s version only in footnote 13. However, his “genpon” text has had no impact on the translation presented above; and the double-bracketed glosses are entirely based on Shibayama’s version of this material.

**After telling us how Rikyū approved the arrangement of the tankei in a 4.5-mat room that had a 1-ken wide toko, the author throws doubt on this in his concluding sentence; and then (in Shibayama’s added material) not only proceeds to tell us that Rikyū never did such things in his own home (where he is not known to have had a 1-ken wide toko in any case), but then goes on to describe an instance where Rikyū praises someone who oriented the tankei so that it faced the ro, rather than diagonally (after which the author then states that this person was one of Rikyū’s most intimate disciples, yet that individual’s biography indicates that he could have been no older than 15 when Rikyū committed seppuku – and surely the overwhelming troubles of Rikyū’s final year of life would have inhibited any attempt to cultivate a relationship of that sort with someone so much younger).

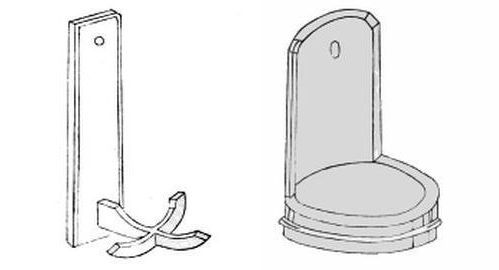

¹Yojōhan ni ha ko-shokudai Genji-tomoshibi ni te mo mochiiru [四疊半ニハ小燭臺源氏火ニテモ用ル].

Ko-shokudai [小燭臺] means a small candlestick. This seems to be an early copyist’s mistake (a ko-shokudai is commonly 5- or 6-sun tall, and this is the kind of candlestick -- often made of Raku-yaki -- that is used in the wabi tearoom today to give additional light to the temae-za or the area in front of the guests’ knees when a te-shoku [手燭] is impractical on account of the long handle); the word should probably just be “shokudai,” which is the object shown below*.

This kind of candlestick is around 2-shaku 5-sun tall or so (measured to the top of the ring that is there to hold a paper-cone -- used as a protection from wind, or as a shade to modulate the intensity of the light -- in place), and was used to give light to the entire room, in the same manner as a tōdai [燈臺] (a stand for an oil-lamp) or Genji-tomoshibi. It is possible that the shokudai was the original light-source used in the rooms of the upper classes, with oil lamps of the various sorts coming into use later (albeit still in remote antiquity).

Genji-tomoshibi [源氏火]† seems to refer to what is usually called a nemuri-tōdai [睡燈臺] or nemuri-tankei [睡短檠], which is sometimes translated as nightlight. It is a lamp-stand (tōdai [燈臺], a stand for an oil lamp; also called a tomoshibi [燈火; but the word is also written simply as 燈, or 火]) that included a metal baffle‡ attached behind the ring-like support for the oil-lamp that kept whatever was on the far side in relative darkness (by directing the light only toward the side of the room toward which the lamp faced).

The lamp-stand was usually designed so that the baffle (or sometimes the baffle and lamp holder, as a single unit) could swivel without having to move the (usually heavy) base. In classical literary works (such as the Genji monogatari [源氏物語]) when a character is described as “turning the lamp to the wall**,” this is what is meant.

Shibayama Fugen’s teihon gives this sentence as yojō-han ni ha ko-shokudai, Genji-tomoshibi nado wo mochii-kuru [四疊半ニハ小燭臺、源氏火抔ヲ古來用ヒ來ル]. The meaning is similar: “in the 4.5-mat room, the ko-shokudai††, Genji-tomoshibi, and so forth, have been used since ancient times.”

__________

*Or, given the context, it is possible that the actual word was supposed to be tōdai [燈臺], meaning a similar sort of stand on which an oil-lamp was stood. A photograph of a tōdai is included under footnote 23.

†The actual pronunciation is unclear. It could also be Genji-bi, or Genji-ka., or even Genji-akari, since all of these would be written with the same three kanji.

‡Sometimes the baffle was cast in openwork (which let a little light seep through); sometimes it was a solid panel (keeping the far side of the room as dark as possible) that often was decorated by a multi-colored painting of the sort for which the period was famous (some scholars suggest that the name Genji-tomoshibi derives not from the role such lamps play in certain pivotal scenes in the Genji monogatari, but because they often featured reproductions of paintings from the illustrated Genji scrolls on one or both sides of the gilded baffle).

**For example, “hi-honoka ni kabe ni somuke” [火ほのかに壁に背け].

††The fact that this word occurs here as well suggests that the mistake was made the first time the text was copied -- or possibly when it was first written -- since a ko-shokudai is the usual object that was commonly used in the tearoom. After the advent of the tankei (created during Jōō’s middle period) the other, earlier, sorts of light-stands seem to have fallen completely out of fashion (only to reappear again during the Edo period, as treasured antiques and arcane curiosities).

²Jōō i-rai tankei mo mochiiraru [紹鷗已來短檠モ用ラル].

I-rai [已來 or 以來] means since then.

In other words, the tankei has been used in the 4.5-mat room since the days of Jōō (though it could be argued that a very similar sort of stand for an oil lamp has been used since the Heian period).

This is probably referring to the sort of tankei shown above. Shibayama Fugen produces an interesting theory of the evolution of the lamp:

◦ The original lamp-stand (as it were) was the tōdai [燈臺] (see the drawing under the sub-note appended to the next footnote).

◦ The next development was the Genji-tomoshibi (where the lamp is placed on a ring that projects on one side of the upright, with a counterbalancing baffle mounted on the other). Both of these he classifies as shin [眞].

◦ From the Genji-tomoshibi evolved the tankei (where the baffle is eliminated, and the upright is fixed on one side of a box-like base that counterbalances the weight of the lamp; the tankei, which (according to Tanaka) was favored by Jōō, is gyō [行].

◦ And the final stage was the kake-tomoshibi [掛燈], which is hung on the hook*; this kind of arrangement (which Tanaka states was created by Rikyū†) is sō [草].

Shibayama’s version of this sentence is: Jōō i-rai tankei wo mo mochiyu [紹鷗以來短檠ヲモ用ユ], which has the same meaning as what is found in the Enkaku-ji manuscript.

___________

*While, at least in the context of chanoyu, the kake-tomoshibi was usually hung on a hook that had been nailed into the toko-bashira, in sixteenth century Korea (and probably before), the hook was attached to a wooden lath (which, in turn, was suspended from a hook or peg attached to the wooden band that circled the upper end of the wall, on which the ceiling rested). This allowed the lamp to be put anywhere needed, and the hook could be raised or lowered along the length of the lath (either through a series of holes into which the hook could be plugged, or because of a bolt-and-nut arrangement that allowed the hook to slide through a channel cut in the middle of the lath).

The example shown above was used for this purpose, and it (or one just like it) was supposedly brought back from Korea by Hosokawa Sansai. This kind of lath was subsequently used, in Japan, to hang the kake-hanaire in situations where no other hook was available (and this is the purpose for which it is best known today).

†There is a problem with Tanaka’s argument, however, since the tō-ka [燈華 or 燈花] (“flower of the lamp”) was one of Jōō’s secret teachings. This related to the hanging of the lamp in the toko, from the same hook nailed into the back wall where a kake-hanaire was usually suspended. Tō-ka meant that the lamp was hung from that hook, with the flame (which can be pronounced ka [火]) taking the place of the flower (which can also be pronounced ka [花 or 華]). This kind of poetic word-play is more typical of Jōō’s approach than it is to Rikyū’s, and implies that the hanging lamp was already a reality during Jōō’s lifetime.

Rikyū’s creation appears to have been the kake-tōdai made of a single piece of bamboo, while Jōō used one constructed (by a specialist craftsman) from several pieces of wood. The two versions of the kake-tōdai are shown in the drawing included in the next footnote. More will be said on this in the next footnote.

³Mukō no toko-bashira ni kugi butte kake-tomoshibi mo yoshi [向ノ床柱ニ釘打テ掛燈モヨシ].

Mukō no toko-bashira [向うの床柱]: the tokonoma usually has four pillars, one in each of the four corners (these are clearly indicated in both of the original sketches that were drawn to illustrate the details of this entry).

Mukō no toko-bashira means the one (of the four) that faces (in other words, is closest to) the ro. This is usually the more “ornamental” of the two pillars that are seen in the front of the toko (the back two are usually all but buried in the plaster), and (more specifically) the pillar closest to the middle of the room (since, at least in theory, the ridge-pole that supports the roof is held up on one end by this pillar -- which is also why it is usually more substantial than the others, which only support the walls to which they are attached).

Kugi butte [釘打って] means (if) a hook had been nailed into (the toko-bashira).

Kake-tomoshibi [掛燈] means a hanging (oil-)lamp. This was often the same sort of lamp that was placed on a free-standing tōdai [燈臺], or on a tankei (which kind of lamp can be seen in the photo under the previous footnote). Or it could have been a simpler saucer of oil, with a collection of wicks resting in it, with the burning end leaning against the side of the saucer*. The number of wicks was not fixed, but the greater the number, the brighter the light (since they were placed in a row).

The saucer of oil, or ceramic oil-lamp was placed on a kake-tōdai [掛燈臺] which, in its simplest form, was made from a length of bamboo, cut like an “L” (like an ichi-jū-giri [一重切], though without any place to put the water, or an upper visor-like ring), as shown on the right.

Here, Shibayama’s teihon has mukō no toko-bashira ni ori-kugi butte kake-tomoshibi wo mo Kyū ha kakerare-shi [向ノ床柱ニ折釘打テ掛燈ヲモ休ハ被掛シ]. The meaning is the same†, but this version adds that Rikyū was the one who apparently began to hang the kake-tomoshibi on the toko-bashira‡.

___________

*The same sort of saucer could also be placed on a tankei or tōdai.

A sketch based on classical illustrations of a group of friends seated around a tōdai, while inspecting Genji’s collection of love letters.

In the case of an ordinary tōdai, the vessel of oil simply sits atop the upright, usually in a saucer-like platform (that helps keep oil from dripping down the stem).

†Rather than kugi [折] in the Enkaku-ji manuscript, Shibayama’s version has ori-kugi [折釘]. This is a hook made by bending a straight length of iron into a hook; and it is the kind of hook still used for this purpose today. Nevertheless, the term indicates that Shibayama’s version was written during the Edo period (when such specific details became more important).

‡This is problematic, because a kake-tōdai had been hung on the toko-bashira since at least the fifteenth century, to illuminate the signature and name-seal(s) on the kake-mono. Perhaps the meaning here is that while the earlier use had focused the light on the interior of the tokonoma, Rikyū nailed the hook for the kake-tōdai on the side of the facing toward the room, so as to light the area between the host and his guests (at least during the shoza).

⁴Tsutanai kyū-dai・naka-ita nado no toki ha itsumo tōdai ka Genji-tōdai nari, tankei mochiite mo kurushikarazu to iu-iu [伹及臺・中板ナドノ時ハイツモ燈臺カ源氏燈臺ナリ、短檠用ヒテモ不苦ト云〻].

Tsutanai [伹い]* means crude, coarse, lacking in refinement. This word is referring to the kake-tomoshibi that was discussed in the previous footnote.

Tanaka explains this in his commentary. The hanging lamp should not be used with things like the kyū-dai daisu or naka-ita because these tana-mono are gyō [行] -- that is, they should be used in the semi-formal rooms -- whereas the kake-tomoshibi is a wabi light-source that is inappropriate because it is too informal for the setting†.

Tankei mochiite mo kurushikarazu [短檠用いても苦しからず] means “there is also no problem with using a tankei” -- since this is another light-source that can be moved around freely in order to eliminate the reflection when the arrangement on the utensil mat is seen from the guests’ seats.

This, and the next, sentence are found only in Shibayama Fugen’s teihon (and the version that quotes from the same source mentioned by Tanaka Senshō); nothing like this is mentioned in the Enkaku-ji manuscript.

__________

*This word is usually written with the kanji tsutanai [拙い] today. The kanji used here, tsutanai [伹い], is virtually unknown in Japanese usage (this, however, was also a feature of Edo period tea literature -- the use of unrecognizable or arcane kanji as another way to prevent the uninitiated from spying out the secrets; such kanji also served to make the texts seem more mysterious).

†I have heard another interpretation of this matter, which turns on another way to understand the word tsutanai -- to mean “unlucky.” In this case, the reference is to the fact that the two tana that are mentioned were painted with highly polished shin-nuri, which would reflect the flame as an undefined ball of light. This kind of apparition could suggest a ghost or other malevolent entity.

While the various free-standing lamps could be moved so that the ball of light was not seen from the guests’ seats (most especially that occupied by the shōkyaku), the kake-tomoshibi is limited by its having to be suspended from a hook nailed into the toko-bashira. It could perhaps be raised or lowered somewhat, but the effect of doing so would have only a minimal impact.

⁵Kake-tomoshibi ha hi no takasa yoku-yoku kangaete kake-beshi [掛燈ハ火ノ高サ能〻考テ可掛].

Hi no takasa yoku-yoku kangaete kake-beshi [火の高さよくよく考えて掛べし] means the height of the flame* should be considered very carefully when hanging (the kake-tōdai).

The hook nailed into the toko-bashira is what they use today not to hang an oil-lamp, but to hang a kake-hanaire [掛け花入]†.

__________

*Given the reluctance to reposition the hook (especially if it was installed by a famous chajin of the past), the length of the upright part of the kake-tōdai might be modified, if necessary.

†Which gives a totally wrong perception, since the ancient rule was that the flowers should appear to be hanging into the room from the garden, inclined toward the temae-za.

Originally, the hook for the kake-hanaire was nailed into the minor-pillar on the other side of the mouth of the toko, since if the hanaire were suspended there, the flowers would naturally achieve the proper orientation. The same thing was true when the hanaire was suspended from the bokuseki-mado.

⁶Hi no takasa fukuro-dana wo okite, jō-dan no dōgu no akari wo ryōken-subeshi [火ノ高サ袋棚ヲ置テ、上段ノ道具ノアカリヲ料簡スベシ].

Jō-dan no dōgu no akari wo ryōken-subeshi [上段の道具の明かりを料簡すべし]: jō-dan [上段] is referring to the ten-ita [天板], the top shelf, of the fukuro-dana, so jō-dan no dōgu [上段の道具] means the utensils* that are arranged on the ten-ita (of the fukuro-dana); akari [明かり] means illumination, the light (that reaches the top shelf); ryōken subeshi [料簡すべし] means (the host) should think about (the illumination of the utensils that are arranged on the ten-ita of the fukuro-dana).

While it would be better for the top shelf to be illuminated appropriately (especially since Jōō and Rikyū usually placed the most important utensils there), the most serious sin would be if a shadow falls across the shelf, so that some utensils are in deep shadow, while the others are illuminated (or, even worse, if the shadow falls across part of a utensil, as if cutting it in half).

Shibayama's source has fukuro-dana wo okite jō-dan no dōgu no akari wo ryōken-subeshi [袋棚ヲ置テ上段ノ道具ノ明リヲ料簡スベシ], which is the same except that the initial phrase (hi no takasa [火の高さ], meaning “with respect to the height of the flame”) is missing. Since we are already considering this topic (in his version), there is no need for these words.

__________

*According to at least some of the modern schools, when using the fukuro-dana, no tea utensils are ever supposed to be placed on the ten-ita. Rather, things like a suzuri-bako [硯箱] (box of writing implements) and ryōshi [料紙] (a pack of writing paper), or antique books, or other things of that sort are supposed to be arranged there. However, there are no historical precedents for any of this (at least none that can be definitively traced back to Jōō or Rikyū).

While it seems that the preference was to restrict the ordinary tea utensils to one of the two shelves of the chigai-dana (the naka-dana and kō-dana), when something like the naka maru-bon was used, it was always placed on the ten-ita of the fukuro-dana, just as on the daisu.

⁷Ikken-toko no toki, tankei oki-yō, hi-guchi tomo ni, sumi-kakete Sōkyū oki-hajimeraruru, Kyū mo mottomo to mōsare-shi nari [一間床ノ時、短檠置ヤウ、火口トモニ、スミカケテ宗及置始メラルヽ、休モ尤ト申レシ也].

Ikken [一間] refers to the distance between the pillars in a traditional Japanese building, which generally measured 6-shaku. Ikken-toko [一間床], therefore, refers to a tokonoma that is 6-shaku wide.

Tankei oki-yō, hi-guchi tomo ni, sumi-kakete [短檠置きよう、火口ともに、角掛けて] means the way to position the tankei, together with its hi-guchi*, is to place it in the corner.

Sumi-kakete [角掛けて] is an especially difficult expression to translate. The verb kakeru [掛ける] means to rest on or lean against. So the tankei is resting on -- or, perhaps, “fitted” or “inserted” into -- the corner. Semantics aside, the implication is that the midline (or the kane with which the tankei is aligned) extends from the corner, rather than from either side, so that the tankei is oriented diagonally. Once this is understood, it follows that the hi-guchi, too, should also be aligned with the same kane (as the oil-lamp is not a fixed part of the tankei, it would theoretically be possible to have the hi-guchi face the ro, or some other direction, even if the tankei itself was oriented diagonally, so this is why the author specified that the hi-guchi should be aligned in the same way as the tankei on which the lamp rests).

According to the latter part of this entry (quoted by Shibayama, but which is missing from the Enkaku-ji manuscript), this means that the tankei is placed in the corner of the mat in front of the toko, oriented on a diagonal (so the flame will give light to the toko, to the interior of the ro, and to the area in front of the guests’ seats, as shown below. (The arrow shows the direction in which the hi-guchi is pointing.)

Sōkyū oki-hajimeraruru, Kyū mo mottomo to mōsare-shi [宗及置き始められる、休も尤もと申うされし] means (this way of placing the tankei) began with (Tennōji-ya) Sōkyū, and Rikyū also said (things should be done in this way).

Shibayama Fugen’s teihon has sate-mata ikken-toko no toki, tankei no oki-yō, hi-guchi no muke-yō, sumi-kakete Sōkyū oki hajimeraruru, Kyū mo mottomo to mōsare-shi nari [扨又一間床ノ時、短檠ノ置様、火口ノ向ケ様、角カケテ宗及置始メラルヽ、休モ尤ト被申シ也], which has the same basic meaning as what is found in the Enkaku-ji manuscript’s text.

Here Tanaka's wording of the last part of this statement is worthy of mention. His “genpon” text has sate-mata ikken-toko no toki, tankei no oki-yō, hi-guchi muke-yō ni suji-kakete mo, kore ha Sōeki no setsu nari [扨又一間床ノ時、短檠ノ置様、火口向様ニスジカケテモ、コレハ宗易ノ説也].

This text concludes with “this was Sōeki's opinion” -- ignoring the reference to Tennōji-ya Sōkyū, and apparently ascribing this innovation to Rikyū himself.

__________

*Hi-guchi is the side of the oil-lamp where the wicks are burning. So the side on which the hi-guchi is found indicates which direction the oil-lamp is pointing.

⁸Saredomo jūbun dōshin ha naki ka [サレドモ十分同心ハ無キカ].

Saredomo [然れども] means however.

Jū-bun dō-shin ha naki ka [十分同じ心はなきか] means “but does this mean that (Rikyū) was in complete agreement (with Sōkyū’s way of orienting the tankei)?*”

The implication is that Rikyū did not agree completely with Sōkyū’s way of doing things†.

It is with this sentence -- and on this note of doubt‡ -- that the Enkaku-ji manuscript version of the text ends.

__________

*More literally, the entire sentence could be translated “however, might [Rikyū] have not been entirely of one mind [with Sōkyū]?”

†Note that this is referring to a 4.5-mat room with a 1-ken toko. Jōō’s 4.5-mat room had a 5-shaku-wide toko; and most rooms of this size today have a toko that is just 4-shaku 2-sun wide. The reader should refer to the incident described in footnotes 23 and 24, below, for Rikyū’s assessment of the situation on an occasion when Sōkyū’s method of orienting the tankei on a diagonal was not being imitated.

‡It really seems that this statement was tacked onto the end of the entry (by someone other than the original author) because this way does not agree with the way things were being done by the Sen family.

⁹The original title of the sketch is yojō-han tomoshibi no oki-dokoro [四疊半ノ置所], which means “the place to put the tomoshibi in the 4.5-mat room.”

Oddly, in the Enkaku-ji manuscript these sketches constitute entry 42 (while the entry to which the sketches refer is 39). Entry 39 is followed by the texts of entries 40, discussing the fuka-sanjō [深三疊], and entry 41, on the naga-yojō [長四疊] The two sketches that are included here are followed by a series of drawings related to these other two types of rooms. Precisely what this means is difficult to explain, especially if we want to buy into the fiction that Nambō Sōkei was responsible for writing the entirety of Book Seven*.

Edo period block-printed books often separate the plates from the text (because the cutting of the two types of blocks required different techniques, and so the work was apparently assigned to different artisans). It is possible, then, that part of an Edo period book on chanoyu (actually, it might have been the written drafts from which the blocks were cut, since a printed document would have declared itself as spurious to Tachibana Jitsuzan) somehow made their way into the Shū-un-an collection of documents.

Since the documents in Nambō Sōkei’s wooden chest were “officially” accessed at least once around the middle of the seventeenth century, by the staff of the Nagoya-based publishing house Fūgetsu-dō [風月堂], in order to prepare the Rikyū chanoyu sho [利休茶湯書] (which was published in Empō 8 [延寶八年], 1680 -- it was his inspection of this collection that motivated Jitsuzan to initiate his own inquiries into the Shū-un-an cache, which subsequently resulted in his creation of the Nampō Roku), it is possible that some of that firm’s other papers inadvertently were mixed in with the Shū-un-an documents.

The three kaki-ire [書入] are interspersed with the two sketches that relate to the present entry.

___________

*It is possible that everything from this title to the end of the entry is spurious (which might be the easiest way to account for the sketches being displaced from the text of this entry).

¹⁰Kono-hashira kugi-butsu kake-tomoshibi [此柱 釘打掛灯] means “on this hashira (the toko-bashira) a hook is nailed (for the) kake-tomoshibi.”