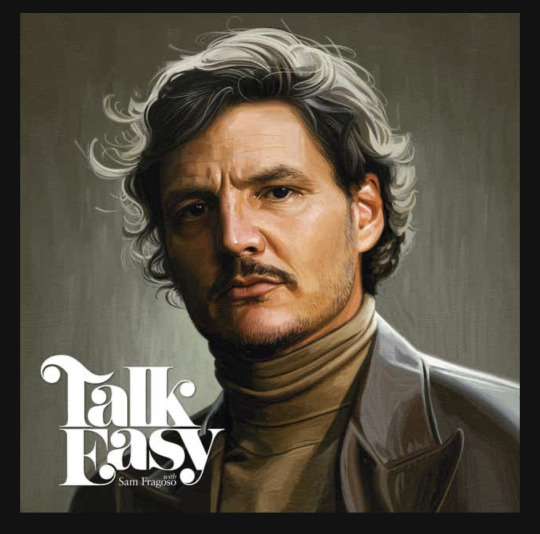

#talk easy podcast

Text

Be Grateful

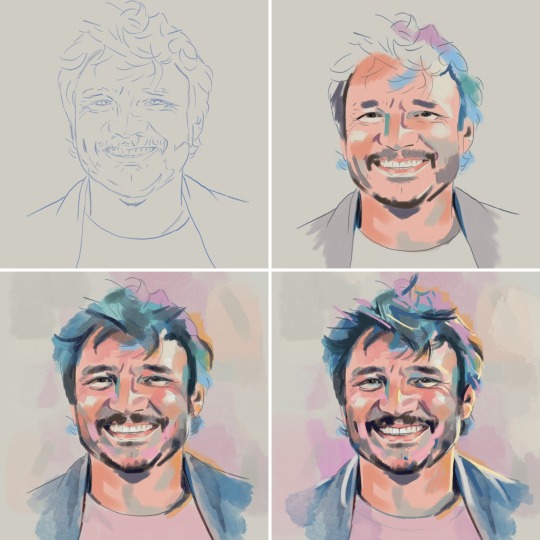

No 𝘺𝘰𝘶 paint Pedro Pascal too much 😂

I have about 15 different subjects waiting in my art queue, but then I saw this image from the Talk Easy podcast and couldn’t help myself. What a breathtaking smile!

Painted on procreate in mixed media.

#Pedro Pascal#pedro pascal art#pedro pascal fandom#pedro pascal fan art#pedro pascal fanart#talk easy podcast#din djarin#the last of us#joel the last of us#Joel Miller#tlou joel#narcos#javier peña#tuwomt#the unbearable weight of massive talent#javier gutierrez#Frankie Morales#Triple Frontier#Oberyn Martell#prince oberyn#agent whiskey#ezra prospect#prospect#prospect movie#Fanart#fanartist#artists on tumblr

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Talk Easy with Sam Fragoso ft. Pedro Pascal (transcript)

I was just going to pull a few choice quotes but this interview was such a genuine pleasure to listen to that in the end I decided to transcribe the whole thing. I know some people will prefer or need to read instead of listening to the podcast so I thought I’d share it here. I tried to capture everything as accurately as possible but this isn’t proofread or anything so let me know if you spot any errors ☺️

To listen to the interview, click here. The transcribed version is under the cut.

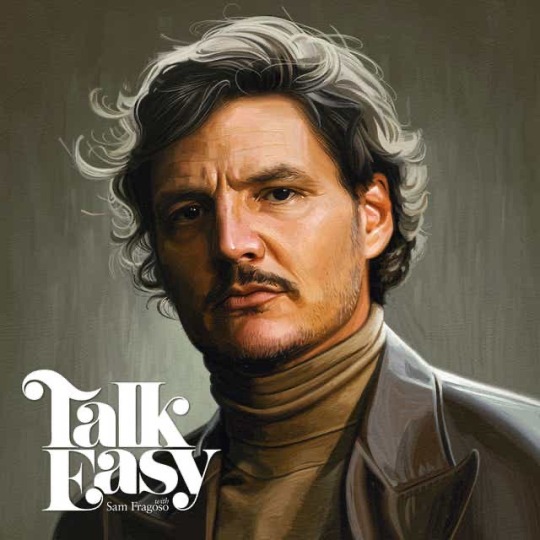

Talk Easy with Sam Fragoso

Episode 274 - Pedro Pascal: A Life of Dreaming (05/15/22)

SF: Pedro.

P: Sí.

SF: How you feelin’?

P: I feel good. It’s nice to be here. There was no traffic, and I like driving.

SF: People on a podcast love to hear about LA people talk about driving and traffic—

P: (laughs) Right.

SF: Historically, they love this.

P: Well I came over from Venice, so it was a long way.

SF: I do know that, I felt bad, I did.

P: There was no traffic!

SF: Okay, good

P: I mean once you get to the 1—let’s do this, let’s just lean all the way in.

SF: Okay, what did you get to, what highway did you take?

P: Once you get to the 110, you know, you start to go through downtown, of course there was traffic, getting to the 5—

SF: Windows down on the way over here?

P: Uh, on the way over…

SF: Okay. You playing music?

P: …and then it got congested. I was actually listening to KPCC, but normally I would be listening to music, and driving kind of fast.

SF: This film, Unbearable Weight of Massive Talent, it’s coming out—

P: Today!

SF: Today. What do you feel like on a day like this? Do you wake up nervous?

P: I don’t know how to feel about it because it’s never been the same. It’s always been, at least through my experience, what seems like unique and different than how I would have expected it to be or feel like, how I fantasized about it as a kid or as an un-working actor. ‘Cause today, this would be like the first thing that I’ve done that is not coming out on a streaming service or during the pandemic or, with me actually in town.

SF: It’s like a movie out in the world, people have to go to theaters to see it, how they used to do.

P: Yeah! Yeah, and we’re still sort of figuring out how to do that again. So, I don’t know what normal is obviously, but, none of it exists in the realm of what my expectations or fears would be, so it sort of eliminates what any expectation would be because I’m like, I don’t know what the hell’s going on on this planet anymore! (laughs) I’m gonna go do a podcast today and there’s no traffic! There’s no traffic, does that mean nobody’s going to the movies?

SF: It’s good to just bring it back to yourself.

P: (laughing) Exactly.

SF: There’s no traffic, does that mean my film is bombing?

P: Exactly.

SF: People aren’t going to the 9:30 showing?

P: Does that mean that the movie that I have a supporting role in is… gonna bomb?

SF: And people say actors are narcissists, and they’re not.

P: They’re just not.

SF: They’re just, they’re like you, you’re selfless.

P: (laughs) Exactly, exactly. I’m thinking about traffic, I’m thinking about the movies.

SF: People please, go see the movie. For his sake.

P: Yeah, seriously. Come on.

SF: In this film, you play a super fan of Nicolas Cage, who offers Nicolas Cage, the actor, in the film, a million dollars to show up to his 40th birthday party in Spain. Now in the film, Nic Cage is playing a version of himself, as actor Nicolas Cage. You are playing I think a slight version of yourself, as someone who actually is a massive fan of Nicolas Cage.

P: Yeah. I think that, um, because of what my timeline is specifically… I was born in ’75, we got cable television pretty early, so there were some of his early movies on HBO, and then my father loved to go to the movies, he would take us to the movies a lot.

SF: On cable, you would watch Valley Girl, Birdy, Racing with the Moon, Rumble Fish…

P: Exactly. Valley Girl in particular because, what do you have, kind of like this sort of, dyed reddish fuchsia hair? Right? What was crazy about that was if you think about it now, it was cool to be in the Valley, and then those crazy delinquents on the other side of the hill in like the cool part of town in Hollywood, and like having real lives… she was just really slumming it. But yeah, so sort of absorbing these movies very young, this was a different time, my parents were very young, we were really kind of unsupervised a lot of the time. As far as TV was concerned, there weren’t too many rules. It took a lot to send us out of the room.

SF: It took them not liking the movie to send you out of the room.

P: Exactly. There were two movies, really, that I remember very vividly having like a huge impact on me. And both of them because I didn’t know what we were going to go see, often, already at a young age I was like ‘I want to see this’ or I knew that we were going to go and I had an expectation around it, but I remember Peggy Sue Got Married, I had no idea what it is, what could it possibly be with a title like that. I had no idea it was directed by Francis Ford Coppola. And the other one was Raising Arizona, and I had no idea, I had never seen… I had actually like, tried to see Blood Simple, because the trailer had appeared before some movie I saw when I was a child and looked so scary? And so visually cool.

SF: I like the image of a 9-year-old Pedro thinking, “yeah I wanna see the Coen brothers’ directorial debut.”

P: I’m telling you—

SF: “Get me in here.”

P: And I remember, like, you know, on drives and stuff like that because there was this kind of—I just remember this… I was really into like scary, thriller-y shit when I was a kid, and still now, but I don’t know, he was like burying a body out in some Texas field or something like that and—

SF: That’s the kind of thing a kid wants to see.

P: (laughs) I just… I guess it was just all the drama that I was after. I don’t know, I remember thinking about the trailer. Did not connect it to when we saw Raising Arizona. And, uh, at the start of Raising Arizona I remember thinking that the whole first few minutes was a trailer for this phenomenal movie? I had never seen anything like that. And had that sort of visual voluptuousness, it was just like, “what is this?” And then the title blazed in and I was like, “oh! This is the movie!” So anyway, there were very impressionable films very very early, with not normal performances from this actor.

SF: Yeah, kind of big, bombastic pieces.

P: Big swings that shouldn’t work, and work… incredibly.

SF: They almost work in spite of themselves. Like they’re so big that they become kind of undeniable.

P: Yeah. But, if you see them again, it isn’t about these performances being big, it’s just completely stylized but also really truthful. I mean, look, I have been kissing. This. Ass. So much—

SF: Oh—

P: (laughs) I know, but I mean it!

SF: I really thought you were going to say, “and I’m tired of it!”

P: (laughs) I’m tired of listening to myself, in terms of the earnestness around this issue, where I guess my favorite thing in life has always been movies, and then going back and re-viewing these performances, I guess I’ve been able to really ponder what it meant to me as a kid seeing something like that for the first time, because it really holds up. It is everything that I would want to be able to pull off, as an actor, is do something completely theatrical, and there be so much truth and skill and believability in the performance.

SF: I think the thing you’re hitting on though is that purity that he seems to have in performing, and I want to kind of understand the pure place from which I think you started to love movies. So, as you said, you were born in Chile, your parents Veronica and José were young liberals in their 20s combating a sort of militaristic regime in that country at the time. They flee, they receive asylum in the Venezuelan embassy. Then they go to Denmark, and then in 1976 you’re one years old, and then you land in San Antonio?

P: I was nine months old when we left Chile. We were in Denmark like under a year, and we ended up in San Antonio.

SF: At what point in your childhood do you begin to understand the origin story of where you came from?

P: It’s hard to piece together because I know that my sister and I went back to Chile without our parents, because our parents weren’t allowed back. I’ve got an enormous family from both sides, and there, visually, the way that I saw it, the presence of what had happened, the fact that my sister and I were the only two out of 34 first cousins, all living in Santiago, Chile, that we were the only two that we were sort of these unique members of the family, being embraced and taken care of with our parents thousands of miles away. And so I started to develop a real fear of like, camouflaged military guards with machine guns that were monitoring, you know… It’s not like they were everywhere or anything like that, I’m sure that there was a sort of normalcy of lifestyle that was achieved for all of my cousins that were—the ones that are older than me, that basically like grew up under a military dictatorship, and yet, the visual of that, knowing somehow, at such a young age, that if my parents were there, they would take them away, and maybe kill them. The way that that lived almost like a kind of supernatural presence in my imagination, was so weird. And then we watched so many movies, and I remember seeing Indiana Jones like running across the plane field with Karen Allen in that white dress and—Karen Allen looked so much like my mother and so I started to imagine things like that, like my father and mother hand in hand like running as like they were being shot at across like a dusty sort of uh, airplane field, what do you call them?

SF: Well you said earlier that, in being interested in Blood Simple, you were searching for a kind of drama, which is kind of surprising considering where you come from, the drama is kind of built in.

P: Yeah. And we’re not talking about it, either. There was a very dramatic mo—

SF: You and your parents aren’t talking about it.

P: No, no, not at all. Nor any of the family members that made it over to us in Texas from Chile. And there was a very dramatic moment in our house when I was a child, ‘cause this Costa-Gavras movie called Missing, with Sissy Spacek and Jack Lemmon, which deals with the military dictatorship in Chile at the time, it’s a true story where an American journalist went missing and was found dead. I remember watching this at home on cable, and there was a moment where Sissy Spacek’s character, she doesn’t make it home before curfew. And she just kind of gets trapped in the city, and um, again, sort of a beautiful, small-framed woman that reminded me so much of my mother and I sort of projected these images of my mother into these characters’ circumstances, and I just remember completely falling apart when she was in danger, when she was so afraid, and imagining that that could have happened to my mother. I remember, yeah, having a little bit of a breakdown.

SF: Well it’s almost like, in the house no one in the family talked about it, and it took film from Hollywood to kind of give language to something no one was giving language to.

P: Yeah. And you know, I could sit through anything at the time and I remember just starting to cry and being like, I can’t watch this. And I was like, gosh, I don’t know, I must have been like, eight?

SF: You’re asking me like I know.

P: Yeah, how old was I?

SF: Maybe eight, that sounds right. Because by the time you’re 12, your family moves to Orange County. You said, “When I was 12 years old, we already enjoyed a very privileged situation and compared to others I was quite a spoiled boy.” Was that true?

P: Yeah, I was spoiled, you know. Our dad was taking us to the movies all the time, we had cable television… You know, eventually once we got into high school years, my mother had found this performing arts program that I had auditioned for and got into, I didn’t like have to work during school, they weren’t comfortable with um, that getting in the way of school work. They didn’t buy me a car, I got like the hand-me-down Volvo for sure. I think culturally what it means to spoil your kid in Chile, at least then, is a little different. Although certainly I was developing needs from lots of John Hughes movies that I was watching when I was a kid, and my dad would literally be like, “Who the hell—” (laughs) you know? Being allowed to see everything, you know, there was one movie I wasn’t allowed to see.

SF: Which one?

P: The Breakfast Club. (laughs) I was dying to see it, I was desperate to see it, and I wasn’t allowed, the argument being it was rated R, but I was like, but, so was First Blood, and you took me to the movies to see that, you know? Essentially, what I came to understand was that my father was like, here are these kids, complaining about their parents (laughs) through the whole movie, their lives look pretty good to me, so no, you’re not seeing that movie.

SF: I like the idea that your dad actually went to go see the movie first, like he screened it for himself, is like, you know what, this is not a picture for my son, he’s gonna start resenting us, he’s gonna develop all these bad habits…

P: Yeah, getting those kind of ideas, like—

SF: He’s smoking weed, then—can’t have that.

P: Yeah, yeah. We could see The Big Chill, you know… the sex, and violence, whatever, but not kids complaining—he’s like, you’re not getting any ideas from this thing.

SF: Was it in high school that you started to develop an interest in acting?

P: No, I wanted to—that was why my mom found this performing arts program, because it was sort of this fantasy that I was sharing with everybody at a very very young age. You know, I knew I wanted to be in movies, started talking about it when I was 7 years old.

SF: And what did people say when you said that?

P: They thought it was cute. I would imagine that maybe I kind of, when given the opportunity to get attention, I would seize it, and entertain and, either annoy or really seduce an audience, as far as um, parents’ friends and stuff were concerned. So maybe they were like yeah, you know, you definitely need a lot of attention. Nobody seemed surprised.

SF: He either needs therapy or he needs acting.

P: (laughing) And I got both. You know, as soon as we moved to California, at the age of—I was 11 turning 12—I immediately was like, oh, we’re getting closer and closer to Hollywood (laughs). You know, really.

SF: That was actually in your head?

P: Absolutely. And so, my mother found like a summer program at South Coast Repertory in Costa Mesa—this was before I got to high school. Other friends found this like, uh, children’s acting program at Laguna Beach, and I auditioned for the kid’s show at the Laguna Beach Playhouse, and got the lead. Uh, it was a play called Wiley and the Hairy Man, and I was Wiley. You know, so at that point, alright, he’s really into this, he doesn’t want to swim anymore, let’s just keep him occupied, and so they didn’t mind it at all as far as how much it kept me out of the house—you know, kept me from wanting to sit in front of the TV all day. Which I do now! ‘Cause I’m an adult and I got what I want. (laughs)

SF: You hear that, kids? If you grow up you can just sit around and watch yourself on TV. (laughs) Oh sorry, he didn’t mention that—

P: (laughing) I didn’t say watch myself!

SF: —he only watches things that he’s in. Or things that he auditioned for and he didn’t get.

P: (laughing) Exactly. Over and over and over again.

SF: We’re not gonna go down that list. It’s, it’d be too—

P: It’s too long.

SF: It’s too fucking long.

P: (laughs) It’s too fuckin’ long, that’s for sure.

SF: The day that changed you, as I understand it—senior year of high school, a friend of your mother’s gives you tickets to Angels in America, downtown Los Angeles, at the Mark Taper?

P: Yeah, before Broadway.

SF: Walk me through that day, that performance.

P: Basically, my mother’s friend said she had theater tickets to something that started at 3 in the afternoon and ended, you know, after 10 PM. And didn’t have the back for it, like, had back issues and so if I wanted these tickets, I could take a friend and she’d give me a note to get out of school early and drive to the Taper and see this play. She didn’t know what it was, and neither did I, but I was like, fuck yeah, get out of school early, go see a play, hell yeah. And it was Oskar Eustis’s production of Angels in America. I think it’s probably one of the 20th century’s, like, most important pieces of literature, much less theater. ‘Cause if you read it on the page it’s as good as a book, you know? And so, I saw that, with this underdeveloped brain, and it was about everything. And I remember it very vividly, so much so that I haven’t really been able to see other versions of it, because of how indelibly marked that first experience was.

SF: What elements in it spoke to you?

P: It just was so fantastic in concept and in drama. I’m sure there were a ton of things that were over my head. It was overtly sexual, it was overtly political, it was overtly intellectual, it was overtly emotional, and so there was just, the visceral experience of these very well-written scenes for one, and these hyper-intellectual speeches, monologues, opening each kind of chapter of the play. And, the political history of it all, and—you know, you started to hear about AIDS before we all hit puberty in my generation, and so little information on that, and I think sex for all of us just seemed so scary.

SF: It seemed scary to you?

P: It seemed scary to all of us, all my friends, you know what I mean? Like, the idea of like, you know, um, being reckless around sex seemed like it just would have such consequences at that point it didn’t matter if you were gay or straight, you know? As we were sort of entering into that phase in life, we started to, you know, look for s—(laughs) have sex, basically. And so, it was just—dealt with all of these things kind of head on—I didn’t know about Roy Cohn, I didn’t know about the Rosenbergs, and I didn’t know enough about McCarthysim, and all of these things, so it just kind of blew my brain wide open. But it was also like an incredible production and the acting was so fierce and I remember particularly between Harper and uh, the character of Harper, the Mormon couple, and Prior and Louis and the way that they had these like, simultaneous kinds of fights, and I just remember being blown away.

SF: Politically and creatively, this piece spoke to you, and it clearly awoke something in a young, 18-year-old version of yourself.

P: I also remember around this time, like, the kinds of impression that certain things made, with movies as well, I remember seeing Sex, Lies, and Videotape, and this four-character piece and just sort of getting into my system. I remember a teacher doing Ntozake Shange’s For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide/When the Rainbow is Enuf, and they literally just… completely laying me out in terms of how dramatically effective these things were in that particular form, that play, that movie, but also like, what you were learning as a kid, you know.

SF: However it happened, it stirred something inside of you that made you think, I should go to New York, attend NYU, and try to make a go at this.

P: Yeah.

SF: You’re looking at me almost terrified.

P: Well there was just so many other movies that took place in New York that I had seen and I had sort of already developed—I’d gone to New York with my father when I was a kid, and I knew, and again developed this fantasy of a life that would start in, you know, first it was going to be Hollywood and then I started to understand that real actors came from New York. And I loved it there. I really did. When I was a kid, I saw Little Shop of Horrors. You know that 2nd Avenue theater where, in ’93 David Mamet’s Oleanna was there and then Stomp came and never left, Stomp was there and I think is still there, as far as I know. And that’s where I find, a little in awe of the privilege sometimes because I had these sort of fantasies that I believed—that I ended up having access to, and also just believed intrinsically that would happen. I got into NYU, my parents did not want me to go. They nearly didn’t let me go. ‘Cause, in our house, like, you had to do well in school, and you had to get into college, and then the rest of it it didn’t matter what you were doing. If these things were being accomplished, if these boxes were being checked, then they didn’t care if you were fucking or doing drugs—you know, and so—

SF: But they did let you go.

P: They did, they ended up letting me go to NYU, yeah. And so I went there. A rude awakening.

SF: Which part?

P: Living there. (laughs) Going from being a spoiled kid in Orange County, a relatively sheltered kid in Orange County, to um, living in New York and living in those winters and everyone way cooler than you, more talented, better I—you know, smarter, sort of like, thinking that you’re the shit and then realizing that you are in-sig-nif-icant, you know? And everyone has as much ambition as you, and just finding space for yourself and the kind of existential sort of confrontation that it was to kind of be in a much, much bigger world.

SF: As you start to find your footing in New York, is there any point in college where you started to think, okay maybe this acting thing, it can happen for me? I feel comfortable in this.

P: There was a classmate of mine my freshman year, this amazing actor named Eugene Byrd, who had started very early. He’s from Philadelphia and he’s still, you know, going today, he’s fantastic. And he had professional representation. In his generosity, he said, I think you should meet my manager, I think you’re really good. And I met his manager, so, before I ended up graduating NYU I was being sent on auditions, because I had professional representation. And to me, so that left me under the impression that it was just going to happen, like immediately.

SF: You do get two quick breaks, don’t you?

P: Well, you know, one of the things that happened while I was still in school, I went to an open call for a movie called Primal Fear. Got called back for it, called back for it again, and screen tested for it.

SF: For the Ed Norton role?

P: Yeah. I think it was something that Leonardo DiCaprio was gonna do, and then that didn’t happen so they started looking. And it was like, the big sought after role. I didn’t get it. It left me with the impression that, while being heartbroken over that, I’ll get the next one. Of course, I did not, and then I did not, and then I did not, and then I did not.

SF: Until… you got the role on Buffy?

P: I did get a part on Buffy, which was incredibly exciting to me. It was the first episode of the fourth season, like one scene and I got killed, and I couldn’t have been more excited about it.

SF: So you have representation, you’re 22, 23. Agent, manager, have a couple parts in something—

P: Got my SAG… job, you know.

SF: Oh you got your SAG? So you had some footing.

P: Oh yeah. Yeah, I thought so.

SF: How does a 23-year-old you make sense of your mom’s passing at that age?

P: It was obviously very traumatic. And, uh, the circumstance of it, is one that uh… Because she died in Chile it means, um, the services are immediate. They don’t, uh, embalm. So it was—it was getting the news and then getting on a plane and flying overnight to Santiago to go to the funeral.

SF: So you take a plane from New York—

P: From LA, I was in Los Angeles when I found out. ‘Cause I’d been testing for a pilot called Dark Angel, which was a really big deal at the time because it was sort of the first thing that James Cameron’s name was attached to after Titanic. And it was like a supporting role, it was like, you know, number four on the call sheet for—which again was gonna be the thing that was gonna change my life.

SF: Instead your life changes in a completely different way.

P: Yeah.

SF: On that plane ride, what’s going through your head?

P: You know, I can’t say I know. I remember that there was a man sitting next to me. He didn’t know what was going on. But, airline travel is often a pretty hostile experience. (laughs) I just remember that there was a man sitting next to me and he was just kind of protective in a way. He could see that I was obviously going through something, and I remember—I don’t know, I don’t know, maybe the stewardess was like, I wasn’t very responsive or something, and she wasn’t, like, being sensitive to something that was pretty obviously going on, and he kind of answered for me and he was a complete stranger. He was like, “he said he doesn’t want,” you know, “he said he doesn’t want it.” And, um, I just can remember that. And, I obviously didn’t sleep, and it’s an overnight flight, and so then you go and… It was summer in Chile as well, so it was very beautiful out, and, um, it was a very beautiful day. And none of that seemed to coincide very well with what was happening. And so, I—I remember it being an unbelievable thing to get through, to be honest with you.

SF: What do you mean by unbelievable?

P: I… I just loved her so much, and uh, she was just kind of the, you know, love of my life in a way and, um. The world doesn’t stop, and the sun doesn’t stop shining, and it was meant to. You know, emotionally, it was hard for me to register, just to comprehend that you could be in a car going to a cremation service and see a family kind of like playing in the yard. Experiencing something so drastically different, right in front of you.

SF: That other people could be experiencing joy.

P: Not even mildly, you know, like a beautiful summer day, and, uh, I—I remember that more than anything. Everything stopped, and I was very resentful that nothing stopped.

SF: That’s kind of the most unnerving part of people dying in your life, which is that they mean so much—in your case, she meant everything—and yet the world continues on.

P: Yeah. I had a hard time with that. Part of carrying on was wanting to get work, and yet it seemed so absurd to feel preoccupied by an audition for maybe a television show or something like that, or a beer commercial.

SF: It felt silly, in contrast to what had happened.

P: Yeah, yeah. It was just too… It seemed too ridiculous, and I did—I did kind of, ‘cause I was kind of—the plan was to stick it out in Los Angeles and, having gotten my Buffy, and like, a theater award, you know, I was like, oh, wow, it’s going really good for me in LA, I’ll stay. But, I think I understood that I didn’t feel like it was—it’s not the, it’s not… I love LA, but it isn’t necessarily the most nurturing environment, you know? It can be nurturing in terms of like going to the beach and going hiking and shit like that, but. Emotionally, it’s a challenge I think for everybody, often. And so, I understood pretty clearly that I wouldn't, I don’t know, that I was in jeopardy of not being able to process this. So I moved back to New York.

SF: You throw yourself into it.

P: Yeah, the original goal was to go out there and to do theater and to be a real actor and everything like that and so I must make meaning out of my life. Big mistake. (laughs) Big mistake. New York was like, “really? You’re back? Yeah, and what?” Um, “back to, back to the restaurant, kid.” ‘Cause I graduated from NYU and I had spent a really brutal year after my graduation, waiting tables and not getting anything, and then being convinced to get out to LA and to give it a shot out there. And getting, you know, a SAG job and testing for a pilot, et cetera. So when I went back to New York… (laughs) You know, no matter what it is, whenever it comes down, I—I wouldn’t want to dissuade anybody from being romantic about their lives, or their goals, but it wasn’t a very practical thing to do, and it felt like a really huge detour, because… I got dropped by my agents, and I couldn’t get arrested, and then 9/11 happened, and it was just a really crazy crazy crazy time.

SF: You said once in an interview, “I had to let go of so many ideas I had about what the pursuit of this career was going to be. It’s a child’s fantasy. There were opportunities, the close call started early for me, but, it didn’t pan out. You find yourself suddenly in your mid-30s and can’t live off the next off Broadway show.”

P: Yeah.

SF: How did you keep going when nothing was working out?

P: I… was a waiter. (laughs) A bad one. But how I got through it was friends and family, really. I don’t want to be too sentimental but, uh, you know, my sister was there to bail me out of anything. She lived in New York for some of that, and I guess, as an adult you develop your own family, which I, uh, had to do and, uh very, very, very close relationships. There was just always somebody to bail me out and cheer me on. And so, I, I don’t really know, it’s sort of like, there was always just a little something to keep you going. I got (laughs), I got a play, I remember losing my representation, and there was an audition that had been scheduled before I got dropped, and I think the only reason that I had been submitted for it was because the character’s first name was Pascal. And it was a world premiere of a play at the Merrimack Repertory Theater in Lowell, Massachusetts, outside of Boston. And I was like, when you got that sort of brutal phone call from the agent saying that, uh, “we are no longer going to represent you,” and you say, “well what about that appointment on Thursday? Do I still go?” and they’re like, “Yeah, sure.” So I went, and uh, I got that part (laughs) and I went to Lowell, Massachusetts, to do this play, I think it was called Fallen. This incredible actress named Monique Fowler was in the play and, I don’t know, we just became friends. She realized what my situation was and was like, “I’ll introduce you to my agent,” I met him and went to an excellent, smaller kind of boutique agency, and that sort of got the ball rolling in terms of regional theater. I think the next thing was a play in Washington, D.C., at the Shakespeare Theater Company, and then a tiny theater in Cape Cod, and I really started to do the regional thing. Went out to Oregon, did Massachusetts quite a few times, did D.C. quite a few times.

SF: So it was starting to come together, piece by piece.

P: Yeah. Piece by piece in terms of like, very far away, you know, outside of the radar professional work, which again started to feel… really important to me, as far as these were big, exciting wins. Also, I didn’t have any experience in classical, uh, training, and would get cast in a production of Hamlet, or Troilus and Cressida, and you know, sort of turn this professional environment into training grounds, and that was cool. And then I got my first play in New York, an off Broadway premiere of a Nilo Cruz play called The Beauty of the Father, and this was the first play produced in New York after he had just won the Pulitzer for Anna in the Tropics. Really big deal. Some nobody named Oscar Isaac was one of the other leads, and that got things sort of going within the off Broadway community a little bit. Took a long time, took years. I had gotten back to New York in August of ’01, went into rehearsals for that play in the winter of ’05. And those years in between felt like a lifetime.

SF: And even from ’05 leading up to Game of Thrones in 2014—

P: (laughs) Yeah

SF: You’re putting it together, piece by piece, somehow remaining undeterred by what I’m sure was an immense amount of failure, and rejection. A longtime friend of yours, and great actor, Sarah Paulson, said of you, “He has a rather righteous sense of self. When I look back at it now, I do know there was always this voice deep down inside of him, that said some day he was going to do what he wanted to do, in the manner in which he wanted to do it.”

P: I wish she had told me that.

SF: She told the New York Times that.

P: (laughs) Because in the meantime she was like, giving me her per diem cash, to help me buy groceries. She bailed me out of so many things, I can’t tell you. She—very soon after my mother had passed, I didn’t have a car in LA and she made her younger sister give me her car. I think that her sister had an alternative but um, basically, those kinds of lifesaving moments. Maybe that is the thing that unconsciously does kind of, sort of keep you going, this sort of sense of self that she was able to identify. I had a really hard time identifying that.

SF: You yourself?

P: Yeah, for sure. What it started to feel like, as you got older and start to get into your 30s and you’re still doing this and you’re still going on auditions and everything, and… you’re not developing other skills—if you’re me. (laughs)

SF: And you start to think, maybe it’s too late to develop other skills?

P: I did, it’s completely too late for me to develop other skills, and so it started to feel like a kind of ruthlessly practical way of living your life. Because it was what you knew how to do, I knew how to go on auditions. It was always just enough, you know, and there would be good months, bad months, good year, bad year. And eventually it just started to become a little bit more consistent. I’ve definitely felt there was sort of, kind of a ceiling for me, in New York, that I wasn’t really graduating from as far as the theater community was concerned. There were two plays that I was up for, that I didn’t get, that would have been jobs through the winter of 2010 going into ’11. One was a revival of Angels in America, at the Signature Theater, directed by Michael Greif, and they just didn’t know where to put me in that, and then the other was, uh, I think they were moving Merchant of Venice from the Park to Broadway. I didn’t get either part, which meant that I was available for pilot season. I just started to throw my focus towards that in a really, really practical way, and again the dream sort of became, maybe getting a regular gig on a series that could help pay the rent.

SF: The pilot season works out, you get a bunch of bit parts—

P: In episodic stuff, yeah.

SF: —in a whole bunch of shows. As we leave, I want to sit with a couple things.

P: Yeah.

SF: When you get the Game of Thrones role, I think somewhere in the middle of shooting, you’re in Belfast,sitting in the great hall of the red keep, watching this big, enormous set around you come alive, and activate, and you are part of it. When you’re sitting there looking at the place you’ve landed, after all you had to go through to get to that moment, how do you sit with that now?

P: It’s definitely like one of the best days I’ve ever had.

SF: Period.

P: Period. Yeah. The set was beautiful, so many of the main players were there, I was sitting down. (laughs)

SF: That is key.

P: (laughing) Instead of like, it is key, instead of like hanging from a cliff or, you know, running, or in the elements, you’re on a set, you’re sitting down, and um, you have a view of everything, from where I was sitting. All the background players in their costumes. It was wonderful. (laughs) It was wonderful. I definitely had let go of expectations like that. Really, you know?

SF: Of that dream you had as a kid.

P: Yeah, of having a job of that caliber. Because, again, like I say, like, getting one of the Law and Order episodes at the time felt like a really huge win. You know, the dream was sort of happening, and so, the size of it had just been so adjusted over the years. When I was a child, I dreamed of sitting in a chair on a show in a scene like that, playing a part like that. I remember being kind of really triggered by the audition process of Game of Thrones because I hadn’t made myself totally invulnerable to the desire for a role that could prove successful, but I had definitely created sort of a healthier expectation around work. And when that started to be challenged again, it really scared me. I was like, oh gosh, it doesn’t feel safe to want something as much as I want this, you know? I had learned that that’s very painful.

SF: Because you had been disappointed too often.

P: (laughs) So often. We’re starting with Primal Fear at the age of 19 and I’m like 38 at this point, and it—Primal Fear wasn’t the only one, you know? There were many in between, close calls. And so being able to sit there and being like, gee, I got this part, I’m doing this part, yeah, it was a moment I really enjoyed, to say the least.

SF: It’s like, you had this childhood dream, the dream worked out a little bit, and very quickly, in your early 20s, then the world kind of came crashing down on you and it made you reset your expectations…

P: Yeah.

SF: And by the time you’re in your early 40s, you’re thinking, it’s just too dangerous, emotionally, to want something again.

P: Yeah.

SF: But to bring it full circle, you’ve done so much in the last five years, that childhood dream has been actualized, and yet I’m curious for you as we leave, did you get what you wanted?

P: Yeah, more than what I wanted. I think that, uh, you have to maintain a relationship to the innocence of your imagination, and also parent it with reality, and keep yourself in check because nothing is ever enough, if you aren’t in a relationship to truth—whatever the hell that’s supposed to mean.

SF: I was going to ask you—

P: (laughs) Yeah, what is truth?

SF: What is truth to you? At this point, you’re 47 now. Or at the very least, what is your truth?

P: Be good to yourself and be good to people. If you want to do any good, you gotta be good, and that’s gotta start with yourself and those that are important to you. And I guess I would say that relationships and having good relationships is more important to me than everything that’s been going on for the last five years, and I know that that’s going to be the sustaining thing, so that’s what I want to—so it’s a matter of staying in relationship to that and also to how fucking exciting it is for Nicolas Cage to be your scene partner on the first day of work. You know, having been flown out of the Los Angeles apocalypse of the pandemic—of 2020, you know, and starting a shoot day in Dubrovnik, Croatia, where your head was split open in Game of Thrones. Like spitting distance from the arena where I shot that fight. Really “pinch me” kind of shit.

SF: It’s always a challenge to remind yourself to kind of pinch yourself and to be like, oh you know, things are kind of working out. And early on in this conversation, you said, you were a little confused by the fact that you and your sister were two of 34 members of your family to remain in America at that time when you came here. I’m thinking about that now because you have this quote here, you said, “I can’t even imagine everything my parents had to go through when they escaped from Chile. And that has left me with an inhereritance of guilt that perhaps has determined the way in which my brothers and I navigate the world.” That guilt that anyone who grows up with some privilege has, whether your parents fled a dictatorship or not, do you still carry that? Or are you now at this point in your life, able to let it go?

P: Mm, we carry it. You know, it’s a generational thing. I think in spite of what my parents went through, they were also very lucky. I think that they carry the guilt of the humble beginnings of their parents. It’s very contradictory because I feel like they didn’t set any limitations, because both my sisters and my brother have been kind of uncompromising in terms of what their pursuits are, and how important their relationships are. And um, out of the four of us, I—maybe they would be very hurt to hear this—I am so attached to them, like I cling to them so much, which—for, I guess, obvious reasons. I wonder what it is about my parents that made us feel such permission to be and do what we want. And so I guess, for that not to have the clearest shape, the most solid shape to just put in front of myself makes me—it isn’t guilt, necessarily, but it is just sort of, you know, some kind of, I don’t know, some sort of like duty, don’t, you know—be grateful. I don’t know, you know? I wish I could—this isn’t necessarily something that I’ve kind of like figured out.

SF: What were you thinking?

P: I was just thinking about the mystery of it, in terms of how there’s still sort of making sense of things and putting it all together and making shape of it. So that you can kind of see it and just try to understand all of the events that have led to me just sitting in front of you and talking about it. I don’t really know how to piece it together, or what it—what it actually means, and—I guess what I was just doing now is just kind of staring blankly at the mystery of, of what does it all mean? (laughs) Oh god. This is the end, right? (laughs) We’ve gotta… You’ve gotta stop me. (laughs) I’m just gonna stop talking so that I don’t continue.

SF: You’re too hard on yourself.

P: I know. God, I hear that a lot. That’s part—that’s a goal. Stop being so hard on yourself.

SF: I don’t know why your parents gave you the permission they did, to be the creative person that you’ve become, but I think I speak for many people listening that I’m glad that they gave you that permission, and uh, I’m grateful you’ve made good use of it.

P: Thank you, Sam.

SF: Are you okay?

P: I am. (laughs) I’m feeling vulnerable but it’s, that’s a good thing.

SF: Thank you for being vulnerable.

P: You’re welcome.

SF: Pedro, lovely to meet you.

P: Lovely to meet you too, Sam. Thank you.

504 notes

·

View notes

Link

“In spite of what my parents went through, they were also very lucky. They carry the guilt of their parents’ humble beginnings. It’s a generational thing, and it made us feel such permission to be and do what we want. It’s some sort of duty. Be grateful.”

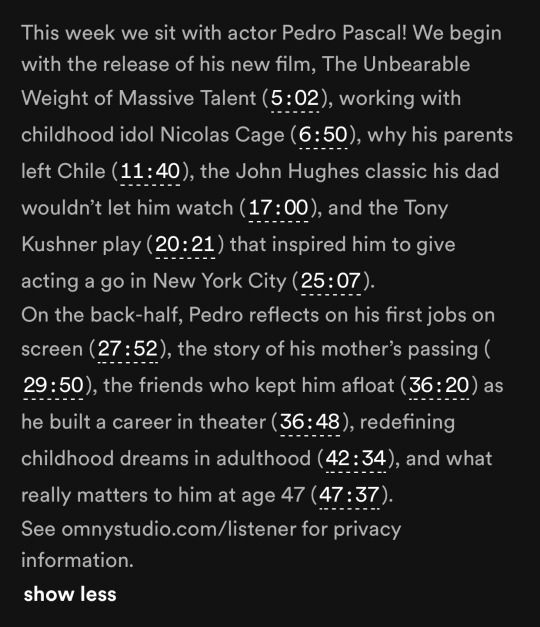

For the long weekend, we return to one of our favorite talks with actor Pedro Pascal! At the top, we discuss his role in The Unbearable Weight of Massive Talent (5:02), working with childhood idol Nicolas Cage (6:50), why his parents left Chile (11:40), the John Hughes classic his dad wouldn’t let him watch (17:00), and the Tony Kushner play (20:21) that inspired him to give acting a go in New York City (25:07).

On the back-half, Pedro reflects on his first jobs on screen (27:52), the story of his mother’s passing (29:50), the friends who kept him afloat (36:20) as he built a career in theater (36:48), redefining childhood dreams in adulthood (42:34), and what really matters to him at age 47 (47:37).

#DON'T listen to this if you do NOT plan on falling HARD and FAST in love with him#I haven't lost my heart this quickly in AGES#GOD#this interview/podcast is sooo fucking good and soft and honest#you just can't help it!!!#(even if you haven't seen any of his work - which to be honest you MUST have#he's in EVERYTHING without you even noticing!)#anyhow: this is the thing that cemented the fact that I will defend the man until the ends of the universe#pedro pascal#podcast#talk easy podcast#(seriously tho: that man's a fucking GOOD EGG!!!)#im sure this is out there already but since he reposted it this morning...#audio

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

listening to Pedro's podcast was so vulnerable, the way he speaks about his love of acting and the hard work to get to where he is, discussion of highs and lows in life and the emotions that bind us all as humans, he speaks so beautifully and the interviewer was amazing and made the conversation feel so open

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

Spotify

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

Just listened to the Talk Easy podcast with Pedro.

Would definitely recommend listening to it. Just a very chill conversation with Pedro, mainly about his journey with acting more than about his big roles.

There's some touching stuff in there and I actually got a little emotional at some points, but I think that's mainly because I just connected with some of the things he was saying.

It's a good interview and really chill, so give it a listen if you can. I caught it on Spotify but I think there's a couple other places you may be able to find it.

#pedro pascal#talk easy#talk easy podcast#the mandalorian#din djarin#javier peña#tuwomt#javi gutierrez

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Trying REALLY HARD here to listen pedro's podcast episode on the train but I just cannot keep a straight face for the life of me

Damn you pedro and your smooth, sexy bedroom voice and your super cheerful laugh, DAMN YOU!!

Please never change ❤️

17 notes

·

View notes

Note

Thoughts on Pedro’s podcast interview?

Hi! Thank you for asking for my opinion! Well, I loved the podcast. I think Pedro seemed comfortable enough to be open and talk about his journey through life. A lot of what he said we already knew as they were things he had said in other interviews, but I loved how he detailed some things we had heard but not in depth. I also think the host was amazing and very sensitive in his questions and the way he handled the info Pedro was sharing. He even felt safe enough to talk about the loss of his mother and how that moment was like, something he rarely talks about. Listening to him talking about his teenage years and how he decided to be an actor was very moving. I particularly loved how he detailed what the play Angels in America meant to him and the social, cultural, artistic and technical importance of it, including but not reduced to the sexual part, when it didn't matter if you were straight or gay, but they were all at that age of just trying to have sex, like, in life, lol.

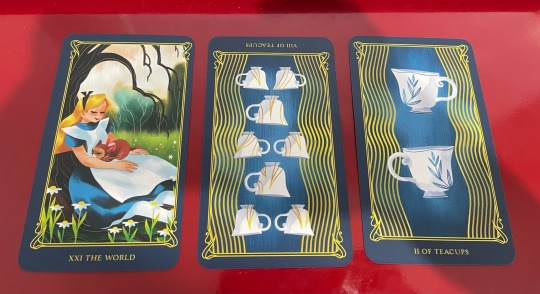

To give a view from the cards, I asked how he felt doing that podcast, what it meant to him, and I pulled The World, 8 of Teacups reversed and 2 of Teacups. The World indicates he had the feeling of coming full circle. It's like he was recounting his jorney until its successful “ending”. You can see Alice with her cat Dinah in the card after returning home from Wonderland. She's changed, she learned so much and she is satisfied with the conclusion of her journey. That is basically how Pedro felt during the podcast, which makes sense, since he said he got more than what he wanted. The 8 of Teacups reversed, however, is telling us he might not be ready to leave some pains behind. He has trouble letting go of this hurt he still carries. The 2 of Teacups shows he felt really in sync with the host, they clicked and he felt comfortable and safe, like I said I thought he was when I heard it.

So he seems to have felt fulfilled and satisfied and he clicked with the host, but there are some things from his past that he might not be ready to let go that showed up in this podcast.

1 note

·

View note

Text

anyway everyone should listen to Camlann

#camlann#camlann podcast#i guess my mo is making memes of all the fandoms i love#but yes everyone should listen to this podcast it's so good!!! and i cannot wait for the next episode#and yeah they only have one episode out so it'll be really easy to get into it!!#please i need people to talk about it!!

134 notes

·

View notes

Text

I finally finished Grant's memoirs, and I keep laughing over Grant's depiction of the surrender at Appomattox.

Cuz like

Grant's traveling to the front when Lee sends the letter asking to meet to arrange the surrender, and the messenger had to track him down on the road. Grant, who'd had no idea that things were going to happen so quickly, isn't dressed for the occasion. He's wearing a private's uniform with only his general's stripes showing his rank, and he doesn't have a sword because he never wears a sword when traveling on horseback. Meanwhile Lee, who plans to go down in style, is impeccably dressed in perfect uniform and carrying this gorgeous sword. And Grant's like, "It didn't occur to me until days afterward just how weird we must have looked." Which is just so relatable, cuz like, this is a climactic moment in a major world conflict, but it's also just another day for a socially awkward dude.

And when Grant gets there, he tells Lee how he remembers him from the Mexican War, but figures Lee couldn't possibly remember him because Grant was sixteen years younger and of a much lower rank. And Lee's like, "No, I remember you and I was pretty impressed." And they get to chatting and reminiscing, until Lee has to remind Grant that they need to discuss this whole surrender thing. And they do, but then they get sidetracked again, and Lee has to once again be the one to get things back on track by saying, "Hey, maybe you should write down those surrender terms."

It's just such a funny image to me. I know this is entirely inaccurate, but I just keep picturing Lee standing there politely while Grant's chatting and having to awkwardly raise his hand and be like, "I hate to be rude, but I'm here to surrender." Grant just wants to be bros and this stupid war keeps getting in the way.

#history is awesome#presidential talk#at long last i can listen to the podcast ep about grant#pretty excited to hear what they have to say about the book#i only retained maybe thirty percent of it cuz the audio wasn't easy to follow#but it had its moments and it's by far the longest book i've read in a long time so that's a satisfying accomplishment

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pedro Pascal Podcast Interviews

These two interviews from 2018 and 2022 are lovely and showcase Pedro’s warmth, empathy, humor, and wit. Russell+Robert (Talk Art) and Sam Fragoso (Talk Easy) do a stellar job engaging Pedro and asking insightful questions. Topics range from art, cinema, his childhood, politics, and family (tw: grief, his mother’s death) to his years as a struggling actor and his current work at the time of the recordings. You can listen on Spotify with a basic (free) account. Each interview runs about 56 minutes.

Nov 2018: Talk Art interview with Pedro Pascal

May 2022: Talk Easy with Sam Fragoso - Pedro Pascal, A Life of Dreaming

#pedro pascal#pedro pascal podcast#talk art#talk easy#sam fragoso#wonderful interviews#makes you love him even more#thoughtful#and yeah that voice#tw: grief#political af#shout-out to the 2018 blue wave#pedro pascal fandom#narcos#game of thrones#unbearable weight of massive talent#mandalorian#all the art discourse makes me want to go to a museum with him

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

language learning revelation i had

#me understanding 5 words in a 20 minute podcast episode: :D :D :D :D#me understanding enough of a podcast episode to be super aware of every word i dont know: :( :( :( :( :(#this is why the b1-b2 plateau is a thing#youre like in the 25-75% range there i think#which is THE MOST ANNOYING#with french i think ive just passed 75 so its fun again#im at like 80 i think#with arabic im at like 1 so its suuuper fun#it's avictory if i can figure out the TOPIC of ap odcast episode#bc like i cant read the titles fhkjghjgkhg#with french i could at least tell the topic from the title but i cant read the titles#so when i figure out what theyre talking about it's like holy shit#and i get like 20 minutes to try and do that#tunisian ones are fun bc they put in a lot of french words#so those are fairly easy to figure out#but also means i catch more and im doing 2 langauges at once so it doesnt take away from the fun#i explained to my dad yesterday my method of just listening to podcasts and trying to understand Anything. ANything At All#and he was like you have a lot of patience#but honestly i think it's the best way to learn#when you really want to know what something is saying and you have no other way to find out but to listen or read it#and like. figure it out#its my favourite way#and at the end the graph flattens out bc like it gets boring again right#this is why we start learning new languages when we plateau#bc we miss the fun

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Idk what it is that makes me fixate so hard on one specific thing for years at a time, but I need it to chill out 😭 DnDads has been my only long-term media interest for like 1 and 1/2 years now, and it’s BORING to only like one thing ever lol I’m BORED!!! I need other things to be interested in, but I struggle with getting into new stuff (other than video games) sooo bad :(

That said, if you have DnD podcast recs that have interesting characters……… GIMME 👀 Also where the early episodes aren’t a nightmare to listen to 🙏 I have never listened to any other DnD podcasts, and I think it’s mostly bc the earlier seasons are always poor audio quality or like 3 hours long 😭 I’m also good with any type of narrative podcast. I just want compelling characters and platonic/familial dynamics pls. Stuff I can write sad shit about!! But also not TOO sad the whole time… maybe a little bit silly idk

So far, ones I’ve written down to listen to are Cast Party and Friends at the Table? I don’t know anything about either of them, though so? Also I keep seeing my mutuals posting Oxventure and Woe.Begone (although the latter isn’t a DnD podcast.. I think?) sooooo let me know your thoughts. And recommendations! Send me your propaganda! Tell me about your blorbos

#the only podcasts I’ve really listened to are dndads and tma#but not the new tma one or whatever it’s called#I don’t really remember anything about it and was never into the fandom anyway#it was interesting ig but just not for me#I listened to it on 2x speed 😭#I’ve also listened to a bit of wtnv and it was fun#but I also just wasn’t super invested. I like the concept a lot though hehe#anyway pls give me podcast recs. you guys can probably assume my favorite types of characters/relationships#I’m easy to read lol#tv show and book series recs are also appreciated#but idk I feel like there are probably a lot of podcasts and audio dramas I’m missing out on#and I drive 45 mins - 1 hour pretty often so it’s nice to have something I can listen to instead of sitting down with#also my last super long-term media interest was fucking danganronpa 😭#which I exclusively fixated on and talked about ad nauseum for like 4 years so. so yeah#chalcy stuff#tma#danganronpa#<- remembered I should probably tag things that aren’t what I usually post lol sorry#hopefully the other stuff doesn’t need tags

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

gotta get all my LINCOLN thoughts DOWN while im relistening to this godforsaken podcast. here's just some stupid observations that i wrote a whole thesis about for no reason

here's two things we know:

- lincoln was raised to always be honest about his feelings

-- despite this, we consistently see lincoln distracting himself whenever big, hard feelings come up

after the grant sauce scene outside the classroom in episode 7, lincoln doesn't take the time to process anything that his father has said to him. he asks normal if HES doing okay after the conversation with Sparrow, and then immediately changes the subject and tells everyone that they should ditch school and go to Sonics so that he wouldn't have to think about it.

and hey, that's all fair; that was some heavy shit to lay on a teenager, and he'd need a lot of time to process it, but we see Linc consistently choosing not to process it.

later, during the grant arc on earth, linc chooses to drive specifically because it's easier not to think when he's driving. when he leaves a voicemail to Marco telling him that he might never talk to him again, a really hard conversation for linc to have, linc ends the phonecall saying, 'no, this was a bad idea, everything's fine-- prank!'

(and it's not fair to say that linc telling scary that they should look for her stepdad first is also evidence that linc does this when part of it was a structural thing to mimic season 1's anchor order, but it IS consistent with linc avoiding hard emotions)

and all of this isn't even inconsistent with him being raised to always be honest! linc never had to deal with big, hard emotions like this, he's only ever been super sheltered and homeschooled and safe. if linc ever felt lonely or bad, his dads would find a way to accommodate him through some form of enrichment, and if the enrichment didn't help, matts made it clear that lincoln's favorite time of the day is when he can just be alone in his room in the space under his bed where it's calm and peaceful and he doesn't have to think about anything. linc is honest about his feelings up until they become so complicated or painful that he doesn't know how to be honest about them. linc is extremely blunt up until he doesn't know how to think about his feelings without getting hurt

grant talks about how he worries linc's relationship with soccer is an emotional distraction. he worries that linc is using soccer the way grant used violence to shut down his thoughts. and sure, linc genuinely loves soccer, it's a harmless interest to have (especially when you don't have the opportunity to have many other hobbies), but Grant recognizes that linc is using it as an emotional crutch-- or at the very least worries that that's what he's doing.

and thats the one thing that grant cant really explain to linc as a parent! if grant stops him from playing soccer JUST because he's worried, he'd have to explain WHY he's worried, and grant cant really do that. he can't talk about how much he likes killing people around his son if he isnt sauced.

and with the main big, scary emotion that lincoln faced in his backstory being mr. kicks, i'd bet lincoln dealt with that feeling by doing a lot of the same. distracting himself with soccer or zoning out entirely. i'd bet grant watched linc avoid any and all discussion about mr. kicks and instead focus on getting better at soccer. there's no way to prove that, but it's consistent with matt's character choices.

so here linc is, going through puberty, spiraling into apathy and avoidance and being like WHATEVER and WHO CARES to everything. this most recent episode was the biggest change in his character yet; he gave up soccer, said it was a waste of time, and broke that goddamn pick.

he doesn't really NEED soccer anymore now that he's learned that he doesn't need an excuse to be dismissive or avoidant anymore; he can just do it. he can just say whatever now. he can just brush people off. he can be abrasive and distant, just like scary.

and it's sad because man, he did really love soccer, even when he was using it for the wrong reasons. he really did love his family and friends. he had the strongest values and the strongest moral compass and he really, really believed in being a good person. but now he's having to deal with big, scary emotions for the first time, and he has no way to know how to deal with them, even with all the therapy his dads gave him. agughghhghghg lincoln li wilson

#talking tag#dndads#MATT IS THE JESUS OF CHARACTER WRITING... TO ME!!#ALLLLLL OF HIS DAD FACTS ARE SO CONSISTENTLY GOOD EVERYTHING HE DOES MAKES SO MUCH SENSE IN CHARACTER AND THE MORE WE HEAR#THE MORE MAKES SENSE ABOUT LINCOLN. WHICH IS CRAZY IN A DND IMPROV PODCAST#when linc is like 'i don't wanna think about it just tell me what i need to do' and anthonys like 'america needs more soldiers like you!'#like fuck........get myson some therapy#and thats not to say he runs from all bad emotions. his anxiety is so bad thatd be a ridiculous claim#linc wears his heart on his sleeve. he cries at the drop of a hat. it's almost always easy to tell exactly how he's feeling#but he definitely has the wilson curse of being very brave in an actionable way but shoving down the emotions that are complicated

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

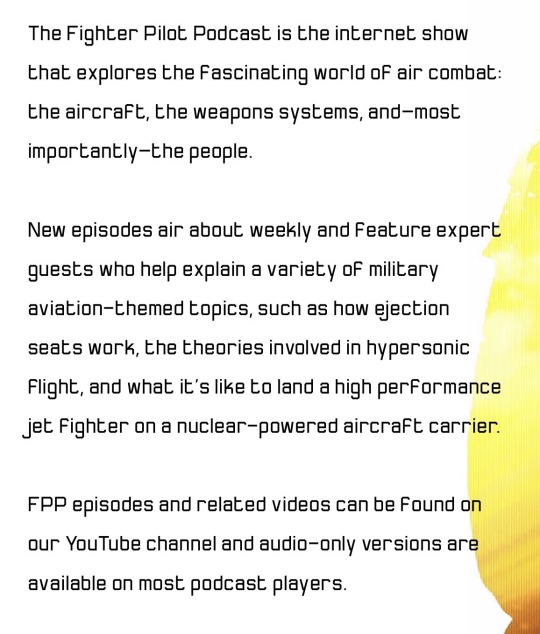

Here are some Top Gun Specific episodes to get you started! Also available in podcast form on every platform.

youtube

youtube

youtube

youtube

youtube

youtube

#Fighter Pilot Podcast#we stan vincent jell o aiello#listen to it all or just specific episodes! I like to jump around to what interests me#learn about fighter pilots and aviation in the military of all areas with jell-o!#literally all topics of aviation#he brings on guests who specialize in the topic#top gun#the episodes are easy to navigate due to their titles and topic centric episodes#he talks with pilots who worked on top gun and maverick#he covers individual airplanes#literally EVERYTHING#and it’s funny! and real! and amazing#give episode zero a listen#top gun: maverick#TOPGUN#Maverick#top gun bts#top gun maverick#listen pls and let me know what you think!!!!#Youtube#tom kazansky#iceman#top gun iceman#pete mitchell#I like research#icemav#research#I like planes#mine

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

juno steel and the blank slate part 2 is free therapy actually

#like 'i think that i did what i could and it was better than nothing' EXCUSE ME#'it's never easy to say goodbye forever to a piece of your life' and 'the past is nice but the future is worth everything' jesus christ#this episode was just SO perfect#vespa and rita being bffs....juno taking over when buddy speaks to dark matters....junos self satisfied voice while talking to sasha....#there will never be enough words for me to articulate how much i love juno he lives inside my heart#the most babygirl#i'm so excited for the finale#AND SEASON 5????? AHHHHH#also very excited to see where they're going with the end of second citadel s4 too but this post is for juno so lets not get into that#tpp#the penumbra podcast#juno steel#tpp spoilers#the penumbra podcast spoilers

145 notes

·

View notes