#tang xue

Photo

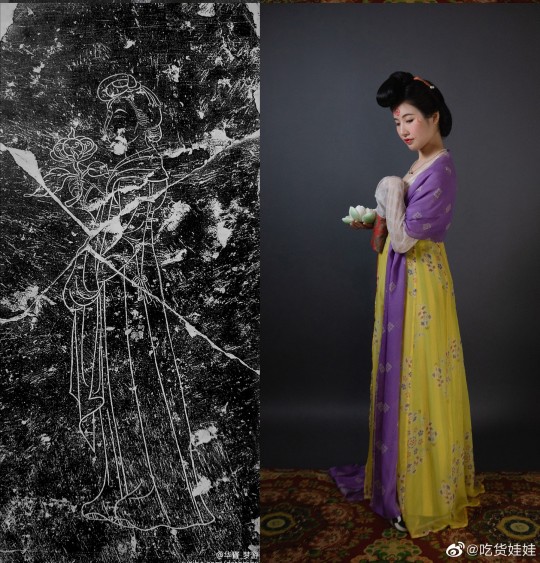

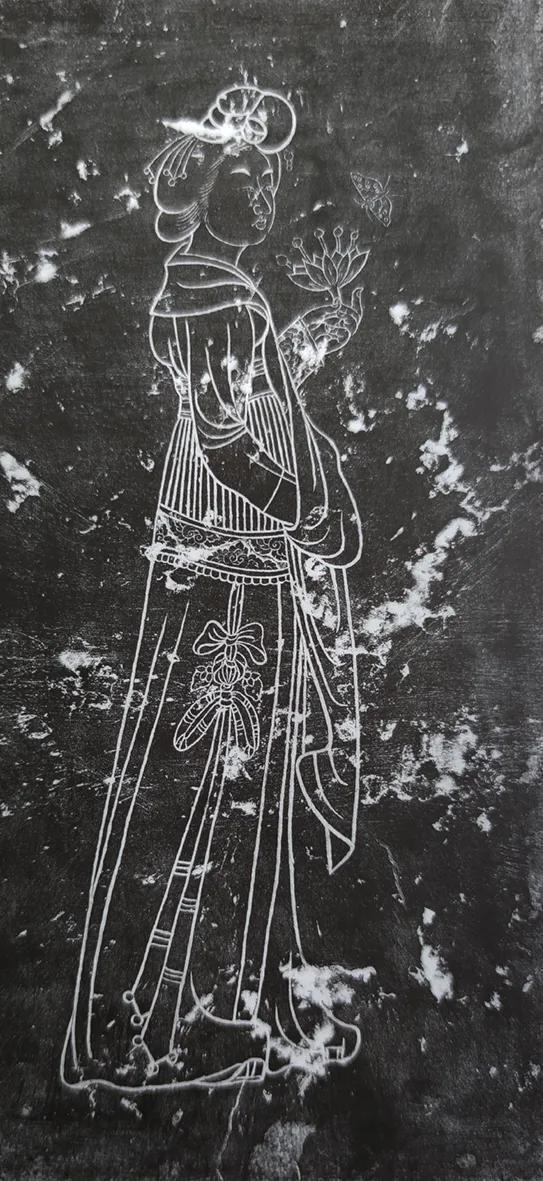

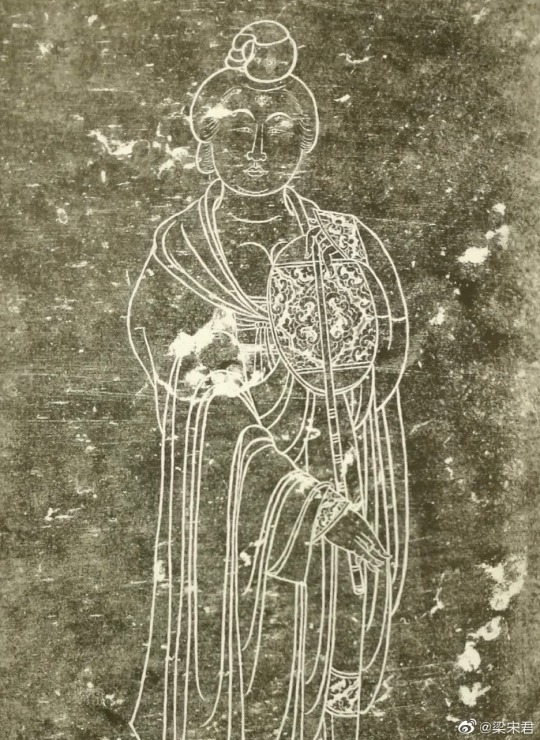

【Historical Reference Artifacts】:

Stone Carving from The Tomb of Xue Jing薛儆 (Emperor Ruizong's son-in-law) & Tang Dynasty Female Figurines:

[Hanfu · 漢服]China Tang Dynasty (960–1127 AD) Chinese Traditional Clothing Hanfu & Hairstyle Based on Tang Dynasty Relics【沉寂千年的光阴】

Around the beginning of Kaiyuan period (708-724 AD) woman fashion & hairstyle

_______

Recreation Work :@吃货娃娃

🔗Weibo:https://weibo.com/1868003212/Mj46arcP9

_______

#Chinese Hanfu#Tang Dynasty (960–1127 AD)#beginning of Kaiyuan period (708-724 AD)#The Tomb of Xue Jing薛儆 (Emperor Ruizong's son-in-law)#锦绣袖缘#锦绣陌腹mofu#Huadian/花钿#裙背带#裙片掩合处#合围#背带#花结/flower knot#chinese traditional clothing#chinese historical fashion#Chinese Costume#chinese history#chinese archaeology#chinese culture relics#chinese art#Chinese Aesthetics#china#吃货娃娃#沉寂千年的光阴#hanfu#hanfu historical relic#hanfu history#漢服#汉服

223 notes

·

View notes

Text

TSOMD as The Onion headlines (part 1)

part 2 / 3

#the sleuth of ming dynasty#tsomd#the fourteenth year of chenghua#sui zhou#dong'er#wang zhi#jin san#xue ling#pei huai#mama cui#tang fan#suitang#my post

493 notes

·

View notes

Photo

let! them! eat!

#the sleuth of ming dynasty#the sleuth of the ming dynasty#wang zhi#tang fan#sui zhou#dong'er#cheng'er#xue ling#tang yu#pei huai#wuyun bulage#duo'erla#ding rong#my art#smushes everyone together at the same table without regard to the timeline#anyway i love them all

107 notes

·

View notes

Text

I just had an epiphany that most of the Blood of Youth characters I headcannon as asexual wear ace colors. Coincidence? Probably

🖤🩶🤍💜

#jin xian#zhao yuzhen#ji xue#tang lian#ace headcanons#headcanon#the blood of youth#少年歌行#shao nian ge xing#gif#my gifs

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Day 2: Xue Tao!

Xue Tao was the daughter of a minor official in Tang Dynasty China. She seems to have a received a good education in early childhood, but her father’s death left she and her mother impoverished and stranded in the city of Chengdu, far away from their likely family in the capital.

Xue Tao became a courtesan, part of Chengdu’s guild of entertainers, and quickly made a name for herself as a poet. The local governor hired her as his official hostess, and she hobnobbed with and befriended the local literati, beginning a salon that continued past the first governor’s death and into the reign of the next; indeed, the succeeding governor, future chancellor Wu Yuanheng, wanted to make her an official part of his staff. Though the Emperor declined the request, Xue Tao was still known as “the female editor” for the rest of her life.

Xue Tao eventually retired to an estate outside of the city, where she continued writing poetry and began a paper-making business; unlike some courtesans, who became concubines to nobles, she never seems to have married. She died there in 832.

Of Xue Tao’s 450 collected poems, roughly a hundred survive today, more than any other female poet of her era.

#xue tao#chinese history#history#poetry#awesome ladies of history#october 2022#watercolor pencils#my art#tang dynasty#hanfu

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Cdrama: Marriage Badge (2023)

💗全集 | 純情皇子愛上穿越萌妃,歡喜冤家奉旨成婚,甜到炸裂!【辰雪令 Marriage Badge 】 #甜宠 #chinesedrama2023

Watch this video on Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uTLzxoDi_aI

#Marriage Badge#辰雪令#Chen Xue Ling#Short Length Series#Web Series#2023#chinese drama#cdrama#Tencent Video#WeTV#youtube#full version#free full version#Hyde#Huang Youtian#Zou Jia Jia#Liu Ze Yu#Tang Wen Qi

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

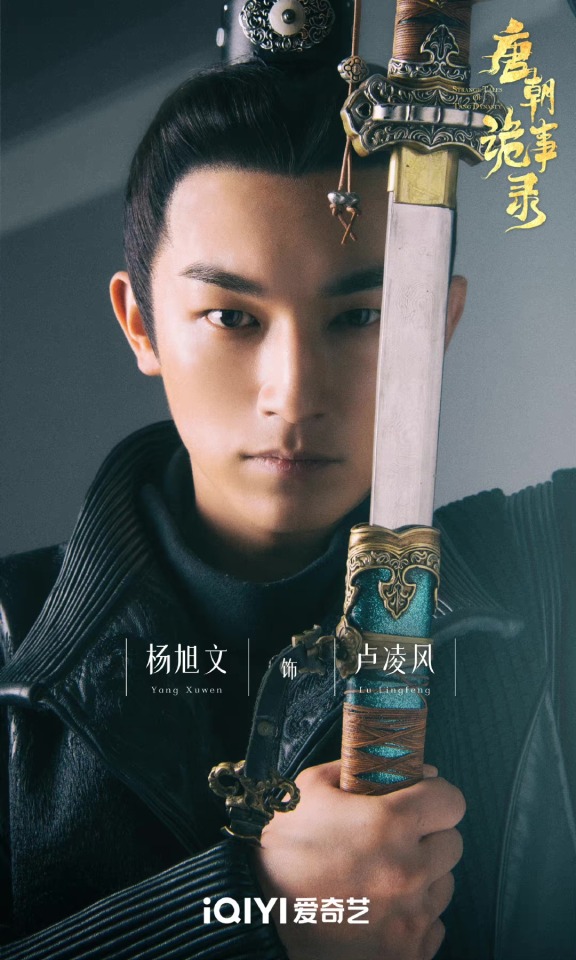

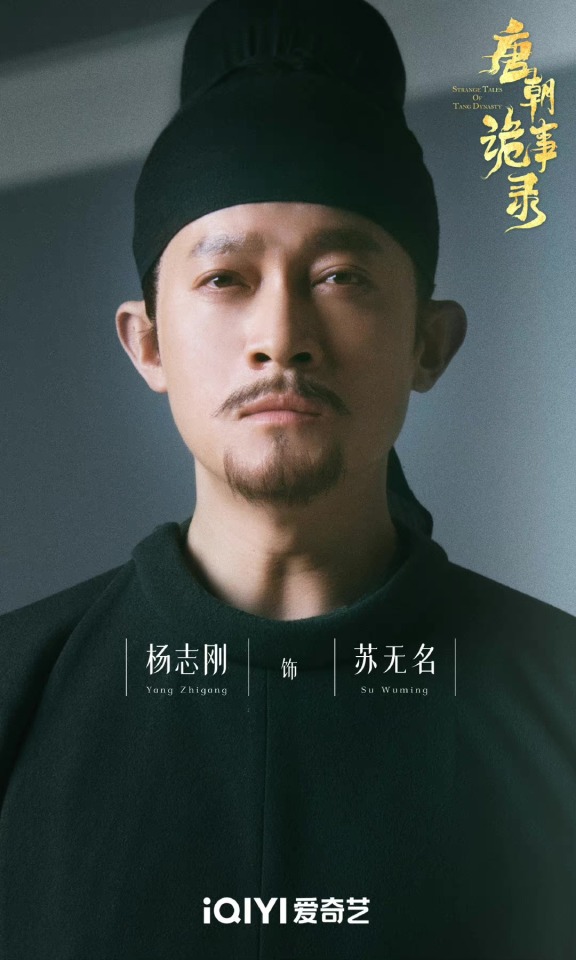

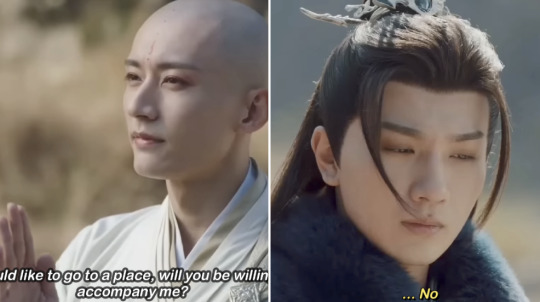

Strange Tales of Tang Dynasty ~ overprotecting disciple

#Xue Huan so cute#Strange Tales of Tang Dynasty#STOTD#cdrama#yang xu wen#character: lu ling feng#yang zhi gang#character: su wu ming#anson shi#character: xue huan#gao si wen#character: pei xi jun

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Title: #StrangeTalesOfTangDynasty #唐朝诡事录

Main Cast: #YangXuWen #YangZhiGang #GaoSiWen #ChenChuang #AnsonShi #SunXueNing

Episodes: 36

Platform: #iQIYI

What an amazing drama, so fun to watch. Detective Di has passed and his student Su Wuming takes the reigns for this drama and he is awesome. Along with Lu Lin Feng they go on this stellar journey solving cases and growing as they go. I had a blast watching it. Su Wuming is actually pretty funny and schemes a lot. The supporting cast and love interests are great. Some complained about the FL but she gets better and better as the drama progresses. It was a quality story with tons of twists and turns and in the end there was a promise of more to come. I honestly can’t wait. Definitely recommended!

#strange tales of tang dynasty#yang xu wen#Yang zhi gang#gao si wen#Chen Chiang#anson shi#sun xue Ning#cdrama

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Li Yubing really only had room in his whole head and heart for one (1) woman his entire life and he’s so valid for that

#skate into love#li yubing#like they showed that tang xue had a crush in high school#but li yubing is straight up like#don't like any girls but xue#even before he liked her romantically he was just like#let me be overly obsessed with this childhood rival/enemy/friend#to the point where everyone was like#bro#bro you okay?#you're doing the rival kate beaton cartoon impresson#bro i think you're letting your being be consumed by this woman#and li yubing is just like#no thought head empty except for tang xue

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

All the Crows in the World (天下烏鴉) (Tian xia wu ya) (2021) Tang Yi

July 28th 2023

#all the crows in the world#天下烏鴉#Tian xia wu ya#2021#tang yi#yi tang#Chen Xuanyu#Xuanyu Chen#Xue Baohe#Baohe Xue#Shujun Huang#short

1 note

·

View note

Text

I was trying to make a Wangxian JTTW AU work in my head and couldn’t get things to click together and then I realized I had picked the wrong two CQL characters so

Xuexiao Journey to the West AU

#‘are you suggesting that—‘ YES#YES XUE YANG AS SUN WUKONG AND XIAO XINGCHEN AS MONK TANG YES YES YES#YOU KNOW THE CHARACTERS WORK PERFECTLY YOU KNOW IM FUCKING RIGHT

1 note

·

View note

Text

Danmei and Baihe C Novels and Manhua Officially Licensed in English

Things are getting licensed fast enough that keeping a list like this up-to-date is basically impossible, but I saw someone asking in the tags so I figured I'd try. All titles are danmei unless otherwise noted (very little baihe is licensed so far). I've included Chinese titles and linked novelupdates for each title when I was able to find them, but sometimes publishers change the original titles so much that I can't track them down, apologies.

Basically: this is everything I know of as of April 12, 2024. There might be more. I tried.

For the latest danmei news, Danmeinews.com is a great resources.

Note that some of this information was sourced from this Carrd, last updated in March 2023.

-

Seven Seas:

The full list of danmei novels licensed by Seven Seas is here. The full list of danmei manhua licensed by Seven Seas is here.

These titles are in various stages of publication, from "entire series released" to "license literally announced less than a week ago." As far as I know, all Seven Seas titles are available world-wide, through major distributors and libraries, and in e-book and print formats.

Mo Xiang Tong Xiu titles:

The Scum Villain's Self-Saving System (Ren Zha Fanpai Zijiu Xitong).

Grandmaster of Demonic Cultivation (Mo Dao Zu Shi)

Grandmaster of Demonic Cultivation (Mo Dao Zu Shi) manhua

Heaven Official's Blessing (Tian Guan Ci Fu)

Meatbun Doesn't Eat Meat titles:

Case File Compendium (Bing an Ben)

The Husky and His White Cat Shizun (Erha he Ta de Bai Mao Shizun)

Remnants of Filth (Yuwu)

Meng Xi Shi titles:

Thousand Autumns (Qian Qiu)

Peerless (Wushuang)

priest titles:

Guardian (Zhenhun)

Stars of Chaos (Sha Po Lang)

Other titles:

Ballad of Sword and Wine (Qiang Jin Jiu) by Tang Jiuqing

I Ship My Rival x Me (Wo Kele Duijia x Wo de CP) manhua by PEPA

Run Wild (Saye) by Wu Zhe

The Disabled Tyrant's Beloved Pet Fish (Canji Baojun de Zhangxin Yu Chong) by Xue Shan Fei Hu

You've Got Mail: The Perils of Pigeon Post (Fei Ge Jiao You Xu Jin Shen) by Blackegg

-

Rosmei:

Rosmei licenses are Singapore distribution rights only. There is a list of international partners organizing group orders here. I've personally placed my orders through Yiggybean, as discussed in reply to this ask.

These titles are only being released as print editions.

Eta: titles that weren't originally on JJWXC (of which there are several here) WILL have e-book editions.

Ning Yuan titles:

BAIHE: At the World's Mercy by Ning Yuan

BAIHE (I think???) The Creator's Grace by Ning Yuan

priest titles:

Coins of Destiny (Liu Yao)

The Defectives (Can Ci Pin)

Drowning Sorrows in Raging Fire (Lie Huo Jiao Chou)

Other titles:

Albert from Earth by Jie Mo Jun

The Bat (Bian Fu) by Feng Nong

Breaking Through the Clouds (Po Yun) by Huai Shang

Don't You Like Me (Ni Shi Bushi Xihuan Wo) by Lv Tian Yi

The Earth is Online (Diqiu Shangxian) by Mo Chen Huan

Everyone Loves the Cannon Fodder (Chuan Cheng Wan Ren Mi de Paohui Zhuma) by Qie Zai Shan Yang

Global Examination (Qianqiu Gao Kao) by Mu Su Li

Gold Class Enforcers (Jinpai Dashou) by Pao Pao Xue Er

How to Survive as a Villain (Chuanyue Cheng Fanpai Yao Ruhe Huming) by Yi Yi Yi Yi

Kaleidoscope of Death (Siwang Wanhuatong) by Xi Zi Xu

The Killer of Killers (Sha Qing) by Wu Yi

Nan Chan by Tang Jiuqing

Obsessed (Ki Ma) by Wu Chen Shui

Wine and Gun (Jiu yu Qiang) by Mengye Mengye

Wow, You Guys are Really Good at Gaming (Nimen Nansheng Da Youxi Hao Lihai O~) by Yi Xiu Luo

-

Peach Flower House:

Peach Flower House titles are primarily for sale through their website and through some distributors, such as Amazon.com. Whether titles are e-book only, print only, or both varies by title.

Da Feng Gua Guo:

The Imperial Uncle (Huang Shu)

Peach Blossom Debt (Taohua Zhai)

Other Titles:

Golden Terrace (Huang Jin Tai) by Cang Wu Bin Bai

In the Dark (Zai Hei An Zhong) by Jin Shisi Chai

Little Mushroom (Xiao Mogu) by Shisi

University of the Underworld by Ziloi

-

Via Lactea:

The full list of danmei novels licensed by Via Lactea is here.

Via Lactea titles are primarily for sale through their website and through some distributors, such as Amazon.com. All titles are either print-only or e-book + print. Only a handful have actually been released, the rest are licensed and presumably in progress.

Jing Shui Bian titles:

Salad Days (Jing Jiu)

Silent Hearts (Mo Mai)

Other Titles:

Dawning (Liming Zhihou) by ICE

Euthanasia by Feng Su Jun

Falling (Luo Chi) by Yu Cheng

Psycho (Feng Zi) by Xiao Yao Zi

Limerence (Wo Xichen Ni Nan Pengyou Henjiule) by Jiang Zi Bei

Lip and Sword (Chun Qiang) by Jin Shisi Chai

The Missing Piece (Maoheshenli) by Kun Yi Wei Lou

Raising Myself in 2006 by Qing Lv

Rose and Renaissance (Wo Zhi Xihuan Ni de Renshe [Yule Quan]) by Zhi Chu

Killing Show (Sha Lu Xiu) by Fox

Soul Vibration (Linghun Saodong) by Dr.solo

To Rule in a Turbulent World (Luan Shi Wei Wang) by Gu Xuerou

-

Monogatari Novels:

It is unclear to me if Monogatari Novel titles are available for world-wide distribution, but there are group orders being organized or I think they can be ordered directly from their webpage; they are based in Spain. These titles can also be ordered from at least some major retailers. Note that there has been some controversy about Monogatari Novels.

BAIHE: A Clear and Muddy Loss of Love (Jing Wei Qing Shang) by Please Don't Laugh

BAIHE: Female General and Eldest Princess (NuJiangjun he Zhang Gongzhu) by Please Don't Laugh

How to Survive as a Villain (Chuan Yue Cheng Fanpai Yao Ru He Huo Ming) manhua by Yi Yi Yi Yi

The Legendary Master's Wife (Chuanshuo Zhi Zhu de Furen) by Yin Ya

The Silent Concubine (Ya Nu) by Qiang Tang

BAIHE: Soulmate manhua by Wenzhi Lizi

-

Aloha Comics:

A tiny, Hawaii-based press focusing on manhua. Titles appear to primarily be available through Diamond Comics. There are also pre-orders on Yiggybean. All of these are pre-orders, though the earliest are coming out by the end of April 2024 (about two weeks after when I'm posting this).

All these titles are manhua!

Day Off by Qing Cai

Here U Are by DJUN

Link Click by Li Haoling and Haoliners (not technically danmei!)

Nirvana in Fire (Lang Ya Bang) by Hai Yan (not technically danmei!)

-

Chaleuria:

As far as I can tell, Chaleuria has not updated their webpage since April 2023, so the current status of in-progress titles is unknown. All titles are digital and/or e-book, and I'm not sure how to purchase them as I haven't tried.

Complete Guide to the Use and Care of a Personal Assistant (Zhuli Shiyong Zhinan) by Why Radiance

Deep in the Act (Ru Xi) by Tongzi

Fake Slackers (Wei Zhuang Xue Zha) by Mu Gua Huang (no longer available)

From Body to Love (Leng Yan E Nan: Xian Shenhou Ai) by Wan Wan Yi Xia

Interstellar Power Couple (Xingji Qiangli Lianyin) by Kun Cheng Xiongmao (no longer available)

Intoxicated Friends (Zui Qing Zhi Pengyou) by Ye Shu Ying

The Long Chase for the President's Spouse (Zongcai Zhui Fu Lu Manman) by Three Thousand Crow Language

Reborn into a Hamster for 233 Days (Chong Shengcheng Cangshu de 233 Tian) by Yi Shu

Records of the Dragon Follower (Cong Long Ji) by Yueren Ge

Urban Tales of Demons and Spirits (Dushi Yaogui Lu) by Qie Er

World Hopping: Avenge Our Love (Ni Wufa Yuliao de Fenshou, Wo Du Neng Gei Ni Song Shang) by Xiaomao Bu Ai Jiao (no longer available)

-

Honorable Mentions:

There are a handful of titles I know of that are official translations of C Novels, where the C Novels aren't danmei or baihe but are often treated as adjacent within fandom (as in: I've seen people shipping characters from them, lol). I've included two above under the entry for titles from Aloha Comics (Link Click and Nirvana in Fire) and here are a couple others I currently know of:

The Grave Robbers' Chronicles (Daomu Biji) by Nanpai Sanshu (six volumes are available in English from Things Asian Press

The Legend of the Condor Heroes (She Diao Yingxiong Chuan) by Jin Yong from St. Martin's Press

Romance of the Three Kingdoms (Sanguo Yanyi), attributed to Luo Guanzhong, available in multiple translations

The Seven Heroes and Five Gallants (Zonglie Xiayi Chuan), attributed to Shi Yukun, there are two translations to English listed at the linked Wikipedia page

Note that to the best of my knowledge both of these are considered very substandard translations. I've personally read the official DMBJ translations and... yeah... and I've heard the LOCH translation is also mediocre.

I will add to the "Honorable Mentions" list if I find any other more mainstream titles with official translations.

Please don't come at me for including a couple classics. The characters shippable, what can I do? I've written fic for Romance of the Three Kingdoms...

-

A handful of other licenses are mentioned on the Carrd I linked at the beginning of this post; I have no idea the status of those titles and wasn't able to find information on them while putting together this post other than what was listed on that Carrd, so I've omitted them.

As a final note, I've personally purchased from every printer on this list EXCEPT Monogatari Novels (I'm holding off because of the controversy and will see how things play out) and Chaleuria (which I vaguely knew existed but nothing beyond that).

Seven Seas translation varies but the editing is general strong and the editions are sturdy and nice. Extras that have come with final volumes are lovely. I am buying literally everything they publish except for You've Got Mail, due to information about the author that was shared with me that the author is a transphobe. Note that Kinnporsche by Daemi is not danmei as it's Thai (and I've heard unsavory things about the author - I don't have a link for that as the information was shared with me on Discord, and I encourage you to do your own research rather than taking my word for it). No judgement if you make a different choice than me, to be clear, I'm just sharing the information I have and why I personally am not buying the books). Note that Seven Seas isn't without controversy, especially for treating their contractors poorly resulting in them unionizing. Some people have also been unhappy with the fidelity of their translations compared to the original Chinese (I've been satisfied personally but ymmv).

Peach Flower House has inconsistent inconsistent editing quality, but the books are very readable, and I'm excited that they're working with translators such as E. Danglars. I haven't bought any of their special editions so can't speak to their extras, but I've bought all their print translations and will continue to do so going forward.

I just got my first title from Via Lactea last week and finished reading it on Sunday, and the translation read very well and there were minimal errors. It also came with a bundle of cute extras, which I wasn't expecting and pleased, and writing this post has caused me to cave and spend $150 to buy the rest of their books. Thank you, tax refund. (Should I spend this money? No. Did I anyway? ...)

No Rosmei titles have actually shipped yet, so I can't speak to their quality, though the previews they've shared on social media (as outlined here, for example) read decently and I'm optimistic. The cover art is also lovely, and they've been communicative and responsive, for example they've already issued a statement related to a recent controversy over perceived poor marketing for At the World's Mercy.

Tl:dr, the above is absolutely everything I personally know about mlm and wlw Chinese novels and manhua that have been licensed for English publication. I hope it helps someone.

Now go forth, and buy some books!

#danmei#baihe#mxtx#priest#priest novels#tang jiuqing#mu su li#meng xi shi#yi yi yi yi#this probably needs a billion other tags but oh well#i've been meaning to write something like this for ages#like there's literally a similar post saved in my drafts#but apparently today is the day i don't have the willpower to not#as also evidenced by my literally buying some of these books while in the middle of putting the post together lmao#i broke a windshield wiper on sunday and SHOULD spend money fixing that instead but here we are#at least it's the passenger side wiper???#anyway as always just tryin to do my part to get people to read more than just mxtx#not that i don't love mxtx#but please guys there's so much amazing stuff out there READ MORE BOOKS

338 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why You Should Watch 少年歌行 | The Blood of Youth

TLDR: Super good, you should absolutely watch this! Not at all a BL/danmei but from what the donghua gave, there’s quite a healthy bit of bromance and brotherhood between the two male leads, and this show has comedy, plot, excellent pacing, exciting wugong moves and conspiracy, plus tons of gorgeous women and men who can all fight!!! CGI is great too, I initially thought this was gonna be a trashy but funny and moderately good wuxia drama but it’s really well-made and it is still funny and really good on all fronts.

*It has a donghua but I haven’t watched it!!!

---

Summary:

Xiao Se is a handsome but relatively poor inn owner in the middle of nowhere on some snowtop mountain, and said inn barely sees any visitors year after year. Just as Xiao Se is deciding whether or not to sell the inn, they finally get one visitor, a young traveler, Lei Wujie who’s traversing jianghu for the very first time on his own, and then they soon get a bunch of hooligans who want to rob the inn. Lei Wujie ‘saves’ Xiao Se by defeating the hooligans but in the process damage the inn; Xiao Se demands payment and Lei Wujie says he needs to get to Xue Yue City to find money to pay him back essentially, so Xiao Se follows him out of his inn in the mountains on a journey.

Along the way, they stumble upon Tang Lian, a skilled and well-known disciple of a famous shifu from Xue Yue City, who’s guarding and escorting a golden coffin to another city, not knowing what is in the coffin. He’s been hunted down repeatedly and ambushed by multiple groups of skilled experts, all coveting what’s inside the golden coffin. Xiao Se and Lei Wujie get accidentally embroiled in the mess, and then realize along the way that a monk - Wu Xin - is in the coffin. And everyone is after Wu Xin, from the demonic sects to other sects in the pugilistic world, all the way to the royal palace.

As Xiao Se and Lei Wujie end up traveling with Wu Xin, conspiracies and past feuds unravel, and Xiao Se is not who he seems to be.

Watch on Youku (YT): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I1xIuBPN-lk (Total 39 episodes, from Dec. 2022 - Jan. 2023)

---

Main Characters:

Xiao Se/Xiao Chuhe (Li Hongyi): The exiled 6th prince who was once a prodigy in martial arts and cultivation before he lost all of it after an attack, and he’s been at the inn ever since. Very well informed of everyone and who’s who, plus all the big happenings in the pugilistic world. Nonchalant, dealing with some issues, very bold and haughty (rightfully so), and this man was a prince and skilled fighter from before too, HAS A LOT OF BAGGAGE, banters a lot with Lei Wujie (cuz this boy is dumb) and is forced to face his demons with the help of Wu Xin. Mysterious, but not really because the moment he walks out everyone knows him like come on he’s the beloved 6th prince before he was exiled

Wu Xin (Liu Xueyi): The son of the demonic sect head before his dad went to war with the royals and was betrayed and defeated, and the demonic sect had to send him over to the royal palace as a hostage, but he gets ‘adopted’ by an old monk and is taught everything that he knows (and was loved) by the old monk. He looks very demonic LMAO more than a monk, super skilled, known for his magic eyes, and he kidnaps Xiao Se and Lei Wujie to be his companions, has a bit of daddy issues too and a lot of pent up anger from when he was younger, but also like super zen at times, and then flippant at other times

Lei Wujie: Dumb husky or golden retriever. Very skilled, pure-hearted, but still very young. SO DAMN FUNNY!!!

---

Why You Should Watch This:

1. Possible bromance between Wu Xin and Xiao Se - So far they’ve been very brotherhood but I expect that all to change soon, their first meeting is hilarious af this is the first thing they say to each other, when Wu Xin asked if Xiao Se would accompany him to place and bro went “No wtf”

I mean look at how demonic and slutty Wu Xin is with his eyes and that jawline and see how close they sitting to each other even though Xiao Se is like get-away-from-me

GUYS WE REALY DO GET BROMANCE!!! HAHAHAHA also i was wrong xiao se at this point isn’t the 团宠 just yet, wu xin is!!! he’s the center of attention do you know how many people ran to catch him when he fainted?!?!??!

AND THEY WERE FORCED TO BE SEPARATED FOR A BIT AND LOOK AT HOW THEY TEARED UP WHEN THEY WERE BACK FACING EACH OTHER WTF YALL WERE BARELY BROS FOR AN HOUR

2. Gorgeous men and women and they all can fight and murder you with their eyes?!?!?! (There’s more than the below LIKE A LOT MORE)

3. COMEDY

Example this dumb boy introducing his big name to everyone and then hitting his head

Example the whole fucking carriage has been exploded to smithereens BUT guess who is literally untouched and still in his bed?? Sleeping beauty Wu Xin

Example Xiao Se praising how amazing Wu Xin is but then like “We’re his hostages but we’re praising him” wtf

4. The CGI!!!! And the fighting sequences are really amazing!!!

---

And lastly am I the only one thinking about Xue Xian and Xuan Min from Copper Coins!!

708 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Nine-headed hermit": the early history of Zhong Kui (and his sister)

Gong Kai's painting Zhongshan Going on Excursion, showing Zhong Kui, his sister and various demons during a journey (wikimedia commons)

Zhong Kui is probably one of the most recognizable figures from Chinese mythology today and continues to star in novels, movies and other works. However, his modern image largely depends on sources the Ming and Qing periods. In this article, I’ll attempt to instead shed some light on some lesser known aspects of his earlier history. You will be able to learn why he was called a “nine headed hermit” despite having only one head, what he had to do with foxes, when his sister was portrayed as an exorcist like him, and more. As a bonus, I’ve included a brief summary of Zhong Kui’s reception in medieval Japan.

The earliest history of Zhong Kui

Zhong Kui’s history goes all the way back to the Zhou period (most of the first millennium BCE). A homophone of his name (鍾馗), zhongkui (終葵; also zhongzui, 終椎) at the time referred to a type of ritual mallet used to expel demons. During the Six Dynasties period first cases of this term (now written as 鍾馗 ori 鍾葵) being used as a personal name start to pop up. The purpose was most likely to confer the protection granted by such objects to a child just through their name. Numerous cases are attested, and it doesn’t seem the bearers of the moniker Zhong Kui can be distinguished by a specific origin, social class or even gender.

The earliest possible reference to a specific supernatural being named Zhong Kui comes from the Taishang Dongyuan Shenzhou Jing (太上洞淵神咒經; “Scripture of the Divine Incantations of the Abyssal Caverns of the Most High”), a Daoist work possibly composed as early as in the fourth century. The oldest surviving copy of the passage concerning Zhong Kui has been identified in a copy from Dunhuang dated to 664. He appears in it as an assistant of king Wu of Zhou and Confucius (sic) who helps them subjugate ghosts and disease demons.

It is not impossible that to the compilers of Taishang Dongyuan Shenzhou Jing Zhong Kui was only a stand-in for an exorcist, though, not a single well defined figure. There’s an eyewitness account of such specialists dressing up in leopard skins, painting their faces red and announcing they are Zhong Kui in another, slightly newer Dunhuang text. It specifies that many Zhong Kui exist, and that they answer to the “General of Five Paths”, an originally apocryphal Buddhist figure eventually canonized as one of the kings of hell (you can find an excellent article about him here).

In any case, regardless of the clear evidence for ambiguous use of the term in earlier times, it is agreed Zhong Kui became a well defined figure by the end of the Tang period. That’s also when legends about his origin started to circulate.

The legend of Zhong Kui

A typical depiction of Zhong Kui as a Tang period official by the Qing period artist Lü Xue (wikimedia commons)

According to the most popular version of Zhong Kui’s origin story, he was a scholar from the Zhongnan Mountains who lived during the reign of Gaozu of Tang (reigned 618-626). He took part either in the imperial examination or the imperial military examination (that’s an ahistorical detail - it was established by Wu Zetian in 702), but failed.

This detail is not elaborated upon further in early accounts, but by the Ming period it was attributed not to lack of skill but rather to prejudice against Zhong Kui’s physical appearance (he is fairly consistently described as dark-skinned, unusually tall, with a bulbous head and excessive facial hair). It’s possible that this new backstory was based in part on experiences of real officials of foreign origin, whose appearance was sometimes mocked by their peers, as already documented in Tang sources. Another possibility is that the descriptions were meant to be exaggerated to the point of making him resemble a demon, though.

Either way, out of despair caused by failure Zjong Kui committed suicide by smashing his head against the steps leading to the imperial palace. However, since in his final words he swore to protect the emperor and his realm, he didn’t return as a vengeful ghost, but rather as a queller of malevolent supernatural entities. Alternatively, he took this role out of gratitude for Gaozu, who was saddened by his death and organized the burial worthy of an honored official for him. Note that in later plays which often serve as the basis for modern adaptations, the burial is typically arranged by a certain Du Ping (杜平), a friend of Zhong Kui from back home.

Apparently a version in which the kings of hell are so impressed by Zhong Kui that they decide to make him the king of the ghosts also exists, though I was unable to track down its original source. In any case, he is associated with Mount Fengdu - one of the terms referring to the realm of the dead - in a poem by Song Wu (宋无; 1260–1340) already. He, or at least generic clerk figures based on his iconography, also sometimes appear in Song period paintings of the Ten Kings.

Several Zhong Kui-like clerks from a depiction of hell in Sermon on Mani's Teaching of Salvation (wikimedia commons)

According to Shih-shan Huang a single example of such a figure has even been identified in a Manichaean context, specifically in the scroll Sermon on Mani’s Teaching on Salvation.

Manichaean curiosities aside, supposedly the first person to be aided by Zhong Kui was emperor Xuanzong of Tang. At some point he fell gravely ill. In a dream, he saw a demon who attempted to steal a flute which was one of his most prized possessions. However, the attempt was foiled by a fearsome giant, who dealt with the thief rather brutally, poking out one of his eyes and then devouring him. After completing this act of demon quelling, he explained that he is Zhong Kui, and how he came to fulfill his current role.

After waking up, Xuanzong felt healthy again. He was so impressed he commissioned Wu Daozi, arguably the most famous artist in China at the time, to prepare a painting of Zhong Kui which could be used as a talisman against any further supernatural issues. Supposedly it left quite the impression on the general populace, and soon numerous images of Zhong Kui started to be distributed as talismans. There is definitely a kernel of truth to this part of the legend, as eyewitness accounts of Wu Daozi’s painting exist, but the work itself is lost.

As a side note, it’s worth pointing out the flute thief demon, despite meeting a gruesome end here, enjoyed a literary afterlife of his own. A certain Li Mingfeng (李鳴鳳), the author of a colophon on one of the earliest surviving Zhong Kui paintings, suggests that the (in)famous rebel An Lushan might have been a reincarnation of this specific entity. While I am not aware of any other attempts at providing him with a backstory, in Ming period retellings of the legend, he received a name, Xu Hao (虛耗).

Zhong Kui’s later career

Zhong Kui’s popularity grew after the Tang period, and he arguably eclipsed figures such as the fangxiang (方相) or the baize (白沢) as the demon queller par excellence. Legends about his origin and his first notable act of demon quelling which I summarized above spread far and wide during the reign of the Song dynasty.

After becoming a well defined figure, Zhong Kui came to be most commonly classified as a ghost (鬼; gui). In texts from the Song and Yuan periods he is often labeled more specifically as a “big ghost” (大鬼, dagui) or “ghost hero” (鬼雄, guixiong). However, his popularity effectively made him a god in popular imagination, and as a matter of fact he is referred to as such. His divinity is not exactly conventional, though. This topic is addressed in Fu Lu Shou Xianguan Qinghui 福祿壽仙官慶會 (The Immortal Officials of Happiness, Wealth and Longevity Gather in Celebration) by the Ming playwright Zhu Youdun (朱有燉; 1379-1435). Zhong Kui says himself that unlike his peers, he has no festival to call his own, and receives no regular offerings - and yet, he still vanquishes malicious entities on behalf of humans as long as talismans showing him continue to be distributed.

Interestingly, despite his long career in texts, no images of Zhong Kui older than the thirteenth century are known. This is mostly a matter of selective preservation, though - we know that depictions of him existed as early as in the ninth century, and that they were mass produced, presumably as woodblock prints, in the tenth. However, he didn’t necessarily look similar to his modern depictions. He actually only came to be depicted as a Tang scholar in the Song period. It seems earlier his costume might have varied.

One thing which seemingly remained consistent when it comes to Zhong Kui’s appearance is his facial hair. This feature is even emphasized in many of his epithets, such as “Old Beard” (老髯, Lao Ran), “Bearded Elder” (髯翁, Ran Wong) or “Bearded Lord” (髯君, Ran Jun). It’s possible that this was initially a way to highlight his vitality and his opposition to disease-causing demons.

Tang and Song sources indicate the state of facial hair could be viewed as an indicator of health. There’s even a handful of peculiar anecdotes about certain emperors, like Taizong of Tang or Renzong of Song, believing their facial hair has supernatural healing powers and offering ailing courtiers concoctions in which it was one of the ingredients. There’s no evidence Zhong Kui’s hair was ever believed to serve a similar purpose, though.

Not all of Zhong Kui’s titles revolve around his beard, though. An interesting example is “Nine-Headed Hermit” (九首山人). The intent isn’t to imply he has nine heads, it’s a multilayered pun instead. The character 馗 in Zhong Kui’s name is a combination of 九, “nine”, and 首, “head”. Referring to him as a “hermit”, literally “man of the mountain”, is likely supposed to show that he traverses areas traditionally believed to be inhabited by demons.

The nine-headed snake Xiangliu (wikimedia commons)

Chun-Yi Tsai suggests that this title also highlights Zhong Kui’s physical prowess by implicitly evoking “a nine-headed serpent known for its tremendous strength in Guideways through Mountains and Seas” (presumably Xiangliu).

Zhong Kui’s strength lets him punish his enemies in various unexpectedly creative ways. The earliest sources already mention he could grind vanquished demons in a mill, for instance. References to eating them are particularly common. Depending on the source, Zhong Kui might simply devour them whole, hunt and prepare them like game animals, chop them up to pickle them, mince them to prepare meat snacks, squeeze them to make juice and wine, and so on.

Such comedically gruesome descriptions are generally limited to textual sources, since violence was rarely depicted in other mediums, even in relation to military topics. Wu Daozi’s lost painting was apparently one of the exceptions, as according to a tenth century description it showed Zhong Kui gouging out the eyes of the captured demon.

Zhong Kui’s sister and other assistants

While Zhong Kui is often depicted in the company of nondescript demons, there are relatively few recurring figures associated with him. The main exception is his sister. The Song period painter Gong Kai (龔開) and his contemporary Li Mingfeng (李鳴鳳) simply refer to her as Amei (阿妹), literally “younger sister”, though here it’s apparently a personal name, following Chun-yi Tsai’s interpretation. Her origin is unknown, and she is not present in any of the early variants of the legend.

Zhong Kui Marrying Off His Sister (wikimedia commons)

Today Zhong Kui’s sister is known chiefly from works of art in various mediums which can be broadly subsumed under the label “Zhong Kui marrying off his sister” (鍾馗嫁妹, Zhong Kui jiamei) which proliferated through the Ming and Qing periods. This label is sometimes applied to earlier paintings too, for example Zhong Kui Marrying Off His Sister (鍾馗嫁妹圖, Zhong Kui jiamei tu) is the conventional modern title of a scroll attributed to the poorly known painter Yan Geng (顏庚). A colophon from the Ming period describing this work calls the figure presumed to be Zhong Kui’s sister Ayi (阿姨; an informal way to refer a maternal aunt) as opposed to Amei.

Chun-yi Tsai states it is not impossible that the woman is supposed to be Zhong Kui’s wife, rather than his sister, though. The painting can be dated to the Yuan period, and there is no evidence for the story of Zhong Kui marrying off his sister before the Ming plays - granted, it is not impossible that it was already in circulation earlier. Still, other paintings showing Zhong Kui marrying off his sister only date to the Qing period. Additionally, the procession might be a parody of paintings showing rural marriages or couples moving to a new house.

While as far as I am aware this eventually went out of fashion, in early sources Zhong Kui’s sister could be portrayed as an exorcist herself. An example can be found in one of the sermons of the Chan monk Yuanwu (圓悟; 1063–1135), in which he states that celebrations on the “Double Fifth” (端午節, duanwu jie) - the fifth day of the fifth month - involved a dance of “Zhong Kui and his little sister”. A reference to performers dressed up as the pair (as well as kings of hell, gods of soil and stove, various warrior deities and more) has alsobeen identified in an account of celebrations in Kaifeng from the end of the reign of the Northern Song dynasty.

Similar evidence can be found in art too. For example, Zheng Yuanyou (鄭元祐; 1292-1364) in a poem inspired by a painting titled Zhong Kui’s Sister (馗妹圖; as far as I am aware, this work has not been identified) states that she travels alongside her brother, that she’s armed with a sword, and that demons fear her. A related portrayal of her is known from a critical review of the works of Si Yizhen (姒頤真), a Song dynasty painter. According to Gong Kai, in one of his paintings she is shown in tattered (or unbuttoned - the term used, 披襟, can mean both) clothes, and chases away a boar attacking her brother. He was evidently not fond of this innovation, and criticizes it as “vulgar” and inappropriate.

It needs to be stressed that Gong Kai’s displeasure wasn’t necessarily tied to presenting Zhong Kui’s sister as a demon queller, though. In fact, he is actually the author of the most famous work portraying her in this role.

Gong Kai's take on Zhong Kui's sister and her attendants (wikimedia commons; cropped for the ease of viewing)

Gong Kai depicted Amei in unusual black makeup, which is also worn by female demons accompanying her (note the one carrying a kitty!). This might be a parody of the sanbai (三白; “three whites”) face painting popular in the Song period. She and her attendants wear robes decorated with depictions of the “five poisons” (五毒), a term referring to animals perceived as particularly dangerous and inauspicious. The exact list varies, though centipedes, scorpions and snakes in particular are mainstays. The five poisons are directly associated with Zhong Kui, as he can be invoked to ward them off. Direct evidence first appears in the Qing period in accounts of the well known Dragon Boat Festival, but it’s not impossible this was an earlier development.

It is presumed that Gong Kai’s painting might depict Zhong Kui and Amei looking for a demonic version of Yang Guifei, as indicated by various hints in colophons. Her portrayals in art are quite diverse, but attributing demonic traits to her would be hardly unparalleled - she could even be described as a “palace demon” (宮妖, gong yao). The decline of the Tang dynasty was blamed on her, and metaphorically she might have been invoked to criticize other people believed to improperly use the power granted to them by the imperial court.

Gong Kai’s painting also depicts a less recurring member of Zhong Kui’s entourage. One of the demons carries a fox, specifically a nine-tailed specimen. The association between this animal and Zhong Kui goes all the way back to the early Tang period. In one of the Dunhuang manuscripts, the demon queller’s entourage includes a nine-tailed fox and a baize, who acted as bringers of good luck alongside him. It’s also worth pointing out that in another text from the same site, his mount during the hunt for a wangliang (魍魎; I will likely cover this entity a future article, stay tuned) is a “wild fox”.

Chun-Yi Tsai attributes the inclusion of a nine-tailed fox among Zhong Kui’s servants as a “family pet” of sorts to the portrayals of this supernatural creature both as an apotropaic antidote to poison (including the five poisons) and as a demon in its own right. It would be a suitable member of Zhong Kui’s entourage both as a conquered malevolent being and as an amplifier for his exorcistic, protective power.

A further possibility is that the association is the result of wordplay. A new year celebration involving a procession of people dressed up as members of Zhong Kui’s entourage, including his sister and various supernatural attendants, was known as dayehu (打夜胡). The homphony between 胡 and 狐, “fox”, might have resulted in the inclusion of the animal among the helpers.

Post scriptum: Zhong Kui in Japan

Zhong Kui, as depicted in Extermination of Evil (wikimedia commons)

Zhong Kui - or rather Shōki, following the Japanese reading of his name - probably reached Japan in the Insei period. Many other figures originating in China reached a considerable degree of popularity in Japan at roughly the same time - Taishan Fujun, Siming, Wudao Dashen, Pangu, Shennong, the examples keep piling up.

The oldest known Japanese depiction of Zhong Kui, which you can see above, is a painting from the twelfth century set known as Extermination of Evil. It might look a bit outlandish compared to most of the other depictions shown through this article, but I was able to locate a very close Chinese parallel:

A Yuan period depiction of Zhong Kui from the collection of the Beijing Library, via Richard von Glahn’s Sinister Way. Reproduced here for educational purposes only.

This is a Yuan period illustration said to be based on Wu Daozi’s painting. Zhong Kui doesn’t look like a Tang scholar yet, and the jacket and wide-brimmed hat are remarkably similar. It seems safe to assume that the Japanese painter was following a similar model - presumably one of the many now lost early depictions of Zhong Kui.

Slightly antiquated iconography surviving far away from the core area associated with a specific figure would hardly be unparalleled - it has been recently suggested that the baize/hakutaku is a similar case, with Japanese depictions and descriptions matching Tang sources fairly closely, but missing the elements which developed in the Song period or later.

For the most part, Zhong Kui fulfilled a similar role in Japan as in China: he was regarded as a fearsome demon queller, and images representing him were distributed for apotropaic purposes. However, it’s also important to note that there were certain innovations. He arrived in Japan at the brink of the middle ages - theologically speaking an era of unparalleled innovation, during which both native and imported figures were interpreted in unexpected ways, leading to the rise of a new “medieval mythology”. Zhong Kui was hardly an exception from this trend.

A “medieval myth” involving Zhong Kui is known from Hoki Naiden (ほき内伝; “Inner Tradition of the Square and the Round Offering Vessels”), an onmyōdō treatise traditionally attributed to Abe no Seimei, but most likely written by one of his descendants in the fourteenth century. Curiously, Zhong Kui’s name is written in it as 商貴 instead of the expected 鍾馗.

Tenkeisei (wikimedia commons)

In the Hoki Naiden, Zhong Kui is still a queller of malevolent supernatural beings. However, instead of being a scorned scholar, he is a yaksha who became the ruler of Rājagṛha, a city in India. He is said to correspond to both the medieval Japanese deity Gozu Tennō (牛頭天王), and to his celestial “double” Tenkeisei (天刑星; from Chinese Tianxingxing), the “star of heavenly punishment” (I covered him here). They are said to be his manifestations respectively on earth and in heaven.

This equation might seem random at first glance, but both of them actually had a lot in common with Zhong Kui: all three were believed to keep demons, especially those causing diseases, in check. Curiously, the reinterpretation of Zhong Kui as a yaksha turned king can also be found in the Genkō Shakusho (元亨釈書), a Kamakura period Buddhist history book. However, I am not aware of any studies examining it in more detail. I assume identifying him as a yaksha was a result of association with Gozu Tennō (I briefly discussed his yaksha credentials here), rather than the other way around, though.

While Hoki Naiden ultimately pertains more to medieval than modern religion, it’s worth noting that an unconventional take on Zhong Kui is still part of an extant tradition. Through history, Zhong Kui could be identified as a dōsojin (道祖神). This term denotes a class of deities meant to protect roads, crossroads and borders of villages. In parts of the Niigata prefecture this form of him is sometimes referred to as Shōki Daimyōjin (鍾馗大明神) today.

Bibliography

Joshua Capitanio, Epidemics and Plague in Premodern Chinese Buddhism

Bernard Faure, Rage and Ravage (Gods of Medieval Japan vol. 3)

Richard von Glahn, The Sinister Way: The Divine and the Demonic in Chinese Religious Culture

Shih-shan Susan Huang, Picturing the True Form. Daoist Visual Culture in Traditional China

Wilt Idema & Stephen H. West, Zhong Kui at Work: A Complete Translation of The Immortal Officials Of Happiness, Wealth, and Longevity Gather in Celebration , by Zhu Youdun (1379–1439)

Chun-Yi Joyce Tsai, Imagining the Supernatural Grotesque: Paintings of Zhong Kui and Demons in the Late Southern Song (1127-1279) and Yuan (1271-1368) Dynasties

55 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Cdrama: Strange Tales of Tang Dynasty (2022)

Gifs of Intro of cdrama “Strange Tales of Tang Dynasty”

【FULL】 高官溺亡黑猫现世 天价红茶为何有血腥味? | 唐朝诡事录 EP01 Strange Tales of Tang Dynasty | 杨旭文 杨志刚 | 古代悬疑剧 | 爱奇艺华语剧场

Watch this video on Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f5V-xnWMBp4

#Strange Tales of Tang Dynasty#唐朝诡事录#Tang Chao Gui Shi Lu#Horror Stories of Tang Dynasty#Strange Legend of Tang Dynasty#2022#iQiyi#Yang Xu Wen#Gao Si Wen#Yang Zhi Gang#Chen Chuang#Anson Shi#Shi Yue An Xin#Sun Xue Ning#Yue Li Na#Zhang Zi Jian#Liu Zhi Yang#Wang Li#Sun Xin Hong#Xiao Yu#Zhang Da Bao#cdrama#chinese drama#youtube#episode 1#1st episode

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Classic Tang Dynasty Hezi Dress Styling

From Hanfu Photographer Shu Ying-Liu Feng Hui Xue

136 notes

·

View notes