#the end of history and the last man

Text

Francis Fukuyama — The End of History and the Last Man

Yoshihiro Francis Fukuyama (born October 27, 1952) is an American political scientist, political economist, and author. He is a Senior Fellow at the Center on Democracy, Development and the Rule of Law at Stanford. He is best-known for his book The End of History and the Last Man (1992).

By way of an Introduction:

The distant origins of the present volume lie in an article entitled “The End of History?” which I wrote for the journal The National Interest in the summer of 1989. In it, I argued that a remarkable consensus concerning the legitimacy of liberal democracy as a system of government had emerged throughout the world over the past few years, as it conquered rival ideologies like hereditary monarchy, fascism, and most recently communism. More than that, however, I argued that liberal democracy may constitute the “end point of mankind’s ideological evolution” and the “final form of human government”, and as such constituted the “end of history”. That is, while earlier forms of government were characterised by grave defects and irrationalities that led to their eventual collapse, liberal democracy was arguably free from such fundamental internal contradictions. This was not to say that today’s stable democracies, like the United States, France, or Switzerland, were not without injustice or serious social problems. But these problems were ones of incomplete implementation of the twin principles of liberty and equality on which modern democracy is founded, rather than of flaws in the principles themselves. While some present-day countries might fail to achieve stable liberal democracy, and others might lapse back into other, more primitive forms of rule like theocracy or military dictatorship, the ideal of liberal democracy could not be improved on.

The original article excited an extraordinary amount of commentary and controversy, first in the United States, and then in a series of countries as different as England, France, Italy, the Soviet Union, Brazil, South Africa, Japan, and South Korea. Criticism took every conceivable form, some of it based on simple misunderstanding of my original intent, and others penetrating more perceptively to the core of my argument. Many people were confused in the first instance by my use of the word “history”. Understanding history in a conventional sense as the occurrence of events, people pointed to the fall of the Berlin Wall, the Chinese communist crackdown in Tiananmen Square, and the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait as evidence that “history was continuing”, and that I was ipso facto proven wrong.

And yet what I suggested had come to an end was not the occurrence of events, even large and grave events, but History: that is, history understood as a single, coherent, evolutionary process, when taking into account the experience of all peoples in all times. This understanding of History was most closely associated with the great German philosopher G. W. F. Hegel. It was made part of our daily intellectual atmosphere by Karl Marx, who borrowed this concept of History from Hegel, and is implicit in our use of words like “primitive” or “advanced,” “traditional” or “modern”, when referring to different types of human societies. For both of these thinkers, there was a coherent development of human societies from simple tribal ones based on slavery and subsistence agriculture, through various theocracies, monarchies, and feudal aristocracies, up through modern liberal democracy and technologically driven capitalism. This evolutionary process was neither random nor unintelligible, even if it did not proceed in a straight line, and even if it was possible to question whether man was happier or better off as a result of historical “progress”.

Both Hegel and Marx believed that the evolution of human societies was not open-ended, but would end when mankind had achieved a form of society that satisfied its deepest and most fundamental longings. Both thinkers thus posited an “end of history”: for Hegel this was the liberal state, while for Marx it was a communist society. This did not mean that the natural cycle of birth, life, and death would end, that important events would no longer happen, or that newspapers reporting them would cease to be published. It meant, rather, that there would be no further progress in the development of underlying principles and institutions, because all of the really big questions had been settled.

The present book is not a restatement of my original article, nor is it an effort to continue the discussion with that article’s many critics and commentators. Least of all is it an account of the end of the Cold War, or any other pressing topic in contemporary politics. While this book is informed by recent world events, its subject returns to a very old question: Whether, at the end of the twentieth century, it makes sense for us once again to speak of a coherent and directional History of mankind that will eventually lead the greater part of humanity to liberal democracy? The answer I arrive at is yes, for two separate reasons. One has to do with economics, and the other has to do with what is termed the “struggle for recognition”.

It is of course not sufficient to appeal to the authority of Hegel, Marx, or any of their contemporary followers to establish the validity of a directional History. In the century and a half since they wrote, their intellectual legacy has been relentlessly assaulted from all directions. The most profound thinkers of the twentieth century have directly attacked the idea that history is a coherent or intelligible process; indeed, they have denied the possibility that any aspect of human life is philosophically intelligible. We in the West have become thoroughly pessimistic with regard to the possibility of overall progress in democratic institutions. This profound pessimism is not accidental, but born of the truly terrible political events of the first half of the twentieth century – two destructive world wars, the rise of totalitarian ideologies, and the turning of science against man in the form of nuclear weapons and environmental damage. The life experiences of the victims of this past century’s political violence – from the survivors of Hitlerism and Stalinism to the victims of Pol Pot – would deny that there has been such a thing as historical progress. Indeed, we have become so accustomed by now to expect that the future will contain bad news with respect to the health and security of decent, liberal, democratic political practices that we have problems recognising good news when it comes.

And yet, good news has come. The most remarkable development of the last quarter of the twentieth century has been the revelation of enormous weaknesses at the core of the world’s seemingly strong dictatorships, whether they be of the military-authoritarian Right, or the communist-totalitarian Left. From Latin America to Eastern Europe, from the Soviet Union to the Middle East and Asia, strong governments have been failing over the last two decades. And while they have not given way in all cases to stable liberal democracies, liberal democracy remains the only coherent political aspiration that spans different regions and cultures around the globe. In addition, liberal principles in economics – the “free market” – have spread, and have succeeded in producing unprecedented levels of material prosperity, both in industrially developed countries and in countries that had been, at the close of World War II, part of the impoverished Third World. A liberal revolution in economic thinking has sometimes preceded, sometimes followed, the move toward political freedom around the globe.

All of these developments, so much at odds with the terrible history of the first half of the century when totalitarian governments of the Right and Left were on the march, suggest the need to look again at the question of whether there is some deeper connecting thread underlying them, or whether they are merely accidental instances of good luck. By raising once again the question of whether there is such a thing as a Universal History of mankind, I am resuming a discussion that was begun in the early nineteenth century, but more or less abandoned in our time because of the enormity of events that mankind has experienced since then. While drawing on the ideas of philosophers like Kant and Hegel who have addressed this question before, I hope that the arguments presented here will stand on their own.

This volume immodestly presents not one but two separate efforts to outline such a Universal History. After establishing in Part I why we need to raise once again the possibility of Universal History, I propose an initial answer in Part II by attempting to use modern natural science as a regulator or mechanism to explain the directionality and coherence of History. Modern natural science is a useful starting point because it is the only important social activity that by common consensus is both cumulative and directional, even if its ultimate impact on human happiness is ambiguous. The progressive conquest of nature made possible with the development of the scientific method in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries has proceeded according to certain definite rules laid down not by man, but by nature and nature’s laws.

The unfolding of modern natural science has had a uniform effect on all societies that have experienced it, for two reasons. In the first place, technology confers decisive military advantages on those countries that possess it, and given the continuing possibility of war in the international system of states, no state that values its independence can ignore the need for defensive modernisation. Second, modern natural science establishes a uniform horizon of economic production possibilities. Technology makes possible the limitless accumulation of wealth, and thus the satisfaction of an ever-expanding set of human desires. This process guarantees an increasing homogenisation of all human societies, regardless of their historical origins or cultural inheritances. All countries undergoing economic modernisation must increasingly resemble one another: they must unify nationally on the basis of a centralised state, urbanise, replace traditional forms of social organisation like tribe, sect, and family with economically rational ones based on function and efficiency, and provide for the universal education of their citizens. Such societies have become increasingly linked with one another through global markets and the spread of a universal consumer culture. Moreover, the logic of modern natural science would seem to dictate a universal evolution in the direction of capitalism. The experiences of the Soviet Union, China, and other socialist countries indicate that while highly centralised economies are sufficient to reach the level of industrialisation represented by Europe in the 1950s, they are woefully inadequate in creating what have been termed complex “post-industrial” economies in which information and technological innovation play a much larger role.

But while the historical mechanism represented by modern natural science is sufficient to explain a great deal about the character of historical change and the growing uniformity of modern societies, it is not sufficient to account for the phenomenon of democracy. There is no question but that the world’s most developed countries are also its most successful democracies. But while modern natural science guides us to the gates of the Promised Land of liberal democracy, it does not deliver us to the Promised Land itself, for there is no economically necessary reason why advanced industrialisation should produce political liberty. Stable democracy has at times emerged in pre-industrial societies, as it did in the United States in 1776. On the other hand, there are many historical and contemporary examples of technologically advanced capitalism coexisting with political authoritarianism from Meiji Japan and Bismarckian Germany to present-day Singapore and Thailand. In many cases, authoritarian states are capable of producing rates of economic growth unachievable in democratic societies.

Our first effort to establish the basis for a directional history is thus only partly successful. What we have called the “logic of modern natural science” is in effect an economic interpretation of historical change, but one which (unlike its Marxist variant) leads to capitalism rather than socialism as its final result. The logic of modern science can explain a great deal about our world: why we residents of developed democracies are office workers rather than peasants eking out a living on the land, why we are members of labor unions or professional organisations rather than tribes or clans, why we obey the authority of a bureaucratic superior rather than a priest, why we are literate and speak a common national language.

But economic interpretations of history are incomplete and unsatisfying, because man is not simply an economic animal. In particular, such interpretations cannot really explain why we are democrats, that is, proponents of the principle of popular sovereignty and the guarantee of basic rights under a rule of law. It is for this reason that the book turns to a second, parallel account of the historical process in Part III, an account that seeks to recover the whole of man and not just his economic side. To do this, we return to Hegel and Hegel’s non-materialist account of History, based on the “struggle for recognition”.

According to Hegel, human beings like animals have natural needs and desires for objects outside themselves such as food, drink, shelter, and above all the preservation of their own bodies. Man differs fundamentally from the animals, however, because in addition he desires the desire of other men, that is, he wants to be “recognised.” In particular, he wants to be recognised as a human being, that is, as a being with a certain worth or dignity. This worth in the first instance is related to his willingness to risk his life in a struggle over pure prestige. For only man is able to overcome his most basic animal instincts – chief among them his instinct for self-preservation – for the sake of higher, abstract principles and goals. According to Hegel, the desire for recognition initially drives two primordial combatants to seek to make the other “recognise” their humanness by staking their lives in a mortal battle. When the natural fear of death leads one combatant to submit, the relationship of master and slave is born. The stakes in this bloody battle at the beginning of history are not food, shelter, or security, but pure prestige. And precisely because the goal of the battle is not determined by biology, Hegel sees in it the first glimmer of human freedom.

The desire for recognition may at first appear to be an unfamiliar concept, but it is as old as the tradition of Western political philosophy, and constitutes a thoroughly familiar part of the human personality. It was first described by Plato in the Republic, when he noted that there were three parts to the soul, a desiring part, a reasoning part, and a part that he called thymos, or “spiritedness.” Much of human behaviour can be explained as a combination of the first two parts, desire and reason: desire induces men to seek things outside themselves, while reason or calculation shows them the best way to get them. But in addition, human beings seek recognition of their own worth, or of the people, things, or principles that they invest with worth. The propensity to invest the self with a certain value, and to demand recognition for that value, is what in today’s popular language we would call “self-esteem.” The propensity to feel self-esteem arises out of the part of the soul called thymos. It is like an innate human sense of justice. People believe that they have a certain worth, and when other people treat them as though they are worth less than that, they experience the emotion of anger. Conversely, when people fail to live up to their own sense of worth, they feel shame, and when they are evaluated correctly in proportion to their worth, they feel pride. The desire for recognition, and the accompanying emotions of anger, shame, and pride, are parts of the human personality critical to political life. According to Hegel, they are what drives the whole historical process.

By Hegel’s account, the desire to be recognised as a human being with dignity drove man at the beginning of history into a bloody battle to the death for prestige. The outcome of this battle was a division of human society into a class of masters, who were willing to risk their lives, and a class of slaves, who gave in to their natural fear of death. But the relationship of lordship and bondage, which took a wide variety of forms in all of the unequal, aristocratic societies that have characterised the greater part of human history, failed ultimately to satisfy the desire for recognition of either the masters or the slaves. The slave, of course, was not acknowledged as a human being in any way whatsoever. But the recognition enjoyed by the master was deficient as well, because he was not recognised by other masters, but slaves whose humanity was as yet incomplete. Dissatisfaction with the flawed recognition available in aristocratic societies constituted a “contradiction” that engendered further stages of history.

Hegel believed that the “contradiction” inherent in the relationship of lordship and bondage was finally overcome as a result of the French and, one would have to add, American revolutions. These democratic revolutions abolished the distinction between master and slave by making the former slaves their own masters and by establishing the principles of popular sovereignty and the rule of law. The inherently unequal recognition of masters and slaves is replaced by universal and reciprocal recognition, where every citizen recognises the dignity and humanity of every other citizen, and where that dignity is recognised in turn by the state through the granting of rights.

This Hegelian understanding of the meaning of contemporary liberal democracy differs in a significant way from the Anglo-Saxon understanding that was the theoretical basis of liberalism in countries like Britain and the United States. In that tradition, the prideful quest for recognition was to be subordinated to enlightened self-interest – desire combined with reason – and particularly the desire for self-preservation of the body. While Hobbes, Locke, and the American Founding Fathers like Jefferson and Madison believed that rights to a large extent existed as a means of preserving a private sphere where men can enrich themselves and satisfy the desiring parts of their souls, Hegel saw rights as ends in themselves, because what truly satisfies human beings is not so much material prosperity as recognition of their status and dignity. With the American and French revolutions, Hegel asserted that history comes to an end because the longing that had driven the historical process – the struggle for recognition – has now been satisfied in a society characterised by universal and reciprocal recognition. No other arrangement of human social institutions is better able to satisfy this longing, and hence no further progressive historical change is possible.

The desire for recognition, then, can provide the missing link between liberal economics and liberal politics that was missing from the economic account of History in Part II. Desire and reason are together sufficient to explain the process of industrialisation, and a large part of economic life more generally. But they cannot explain the striving for liberal democracy, which ultimately arises out of thymos, the part of the soul that demands recognition. The social changes that accompany advanced industrialisation, in particular universal education, appear to liberate a certain demand for recognition that did not exist among poorer and less educated people. As standards of living increase, as populations become more cosmopolitan and better educated, and as society as a whole achieves a greater equality of condition, people begin to demand not simply more wealth but recognition of their status. If people were nothing more than desire and reason, they would be content to live in market-oriented authoritarian states like Franco’s Spain, or a South Korea or Brazil under military rule. But they also have a thymotic pride in their own self-worth, and this leads them to demand democratic governments that treat them like adults rather than children, recognising their autonomy as free individuals. Communism is being superseded by liberal democracy in our time because of the realisation that the former provides a gravely defective form of recognition.

An understanding of the importance of the desire for recognition as the motor of history allows us to reinterpret many phenomena that are otherwise seemingly familiar to us, such as culture, religion, work, nationalism, and war. Part IV is an attempt to do precisely this, and to project into the future some of the different ways that the desire for recognition will be manifest. A religious believer, for example, seeks recognition for his particular gods or sacred practices, while a nationalist demands recognition for his particular linguistic, cultural, or ethnic group. Both of these forms of recognition are less rational than the universal recognition of the liberal state, because they are based on arbitrary distinctions between sacred and profane, or between human social groups. For this reason, religion, nationalism, and a people’s complex of ethical habits and customs (more broadly “culture”) have traditionally been interpreted as obstacles to the establishment of successful democratic political institutions and free-market economies.

But the truth is considerably more complicated, for the success of liberal politics and liberal economics frequently rests on irrational forms of recognition that liberalism was supposed to overcome. For democracy to work, citizens need to develop an irrational pride in their own democratic institutions, and must also develop what Tocqueville called the “art of associating,” which rests on prideful attachment to small communities. These communities are frequently based on religion, ethnicity, or other forms of recognition that fall short of the universal recognition on which the liberal state is based. The same is true for liberal economics. Labor has traditionally been understood in the Western liberal economic tradition as an essentially unpleasant activity undertaken for the sake of the satisfaction of human desires and the relief of human pain. But in certain cultures with a strong work ethic, such as that of the Protestant entrepreneurs who created European capitalism, or of the elites who modernised Japan after the Meiji restoration, work was also undertaken for the sake of recognition. To this day, the work ethic in many Asian countries is sustained not so much by material incentives, as by the recognition provided for work by overlapping social groups, from the family to the nation, on which these societies are based. This suggests that liberal economics succeeds not simply on the basis of liberal principles, but requires irrational forms of thymos as well.

The struggle for recognition provides us with insight into the nature of international politics. The desire for recognition that led to the original bloody battle for prestige between two individual combatants leads logically to imperialism and world empire. The relationship of lordship and bondage on a domestic level is naturally replicated on the level of states, where nations as a whole seek recognition and enter into bloody battles for supremacy. Nationalism, a modern yet not-fully-rational form of recognition, has been the vehicle for the struggle for recognition over the past hundred years, and the source of this century’s most intense conflicts. This is the world of “power politics,” described by such foreign policy “realists” as Henry Kissinger.

But if war is fundamentally driven by the desire for recognition, it stands to reason that the liberal revolution which abolishes the relationship of lordship and bondage by making former slaves their own masters should have a similar effect on the relationship between states. Liberal democracy replaces the irrational desire to be recognised as greater than others with a rational desire to be recognised as equal. A world made up of liberal democracies, then, should have much less incentive for war, since all nations would reciprocally recognise one another’s legitimacy. And indeed, there is substantial empirical evidence from the past couple of hundred years that liberal democracies do not behave imperialistically toward one another, even if they are perfectly capable of going to war with states that are not democracies and do not share their fundamental values. Nationalism is currently on the rise in regions like Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union where peoples have long been denied their national identities, and yet within the world’s oldest and most secure nationalities, nationalism is undergoing a process of change. The demand for national recognition in Western Europe has been domesticated and made compatible with universal recognition, much like religion three or four centuries before.

The fifth and final part of this book addresses the question of the “end of history,” and the creature who emerges at the end, the “last man.” In the course of the original debate over the National Interest article, many people assumed that the possibility of the end of history revolved around the question of whether there were viable alternatives to liberal democracy visible in the world today. There was a great deal of controversy over such questions as whether communism was truly dead, whether religion or ultranationalism might make a comeback, and the like. But the deeper and more profound question concerns the goodness of Liberal democracy itself, and not only whether it will succeed against its present-day rivals. Assuming that liberal democracy is, for the moment, safe from external enemies, could we assume that successful democratic societies could remain that way indefinitely? Or is liberal democracy prey to serious internal contradictions, contradictions so serious that they will eventually undermine it as a political system? There is no doubt that contemporary democracies face any number of serious problems, from drugs, homelessness and crime to environmental damage and the frivolity of consumerism. But these problems are not obviously insoluble on the basis of liberal principles, nor so serious that they would necessarily lead to the collapse of society as a whole, as communism collapsed in the 1980s.

Writing in the twentieth century, Hegel’s great interpreter, Alexandre Kojève, asserted intransigently that history had ended because what he called the “universal and homogeneous state” – what we can understand as liberal democracy – definitely solved the question of recognition by replacing the relationship of lordship and bondage with universal and equal recognition. What man had been seeking throughout the course of history – what had driven the prior “stages of history” – was recognition. In the modern world, he finally found it, and was “completely satisfied.” This claim was made seriously by Kojève, and it deserves to be taken seriously by us. For it is possible to understand the problem of politics over the millennia of human history as the effort to solve the problem of recognition. Recognition is the central problem of politics because it is the origin of tyranny, imperialism, and the desire to dominate. But while it has a dark side, it cannot simply be abolished from political life, because it is simultaneously the psychological ground for political virtues like courage, public-spiritedness, and justice. All political communities must make use of the desire for recognition, while at the same time protecting themselves from its destructive effects. If contemporary constitutional government has indeed found a formula whereby all are recognised in a way that nonetheless avoids the emergence of tyranny, then it would indeed have a special claim to stability and longevity among the regimes that have emerged on earth.

But is the recognition available to citizens of contemporary liberal democracies “completely satisfying?” The long-term future of liberal democracy, and the alternatives to it that may one day arise, depend above all on the answer to this question. In Part V we sketch two broad responses, from the Left and the Right, respectively. The Left would say that universal recognition in liberal democracy is necessarily incomplete because capitalism creates economic inequality and requires a division of labor that ipso facto implies unequal recognition. In this respect, a nation’s absolute level of prosperity provides no solution, because there will continue to be those who are relatively poor and therefore invisible as human beings to their fellow citizens. Liberal democracy, in other words, continues to recognise equal people unequally.

The second, and in my view more powerful, criticism of universal recognition comes from the Right that was profoundly concerned with the leveling effects of the French Revolution’s commitment to human equality. This Right found its most brilliant spokesman in the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, whose views were in some respects anticipated by that great observer of democratic societies, Alexis de Tocqueville. Nietzsche believed that modern democracy represented not the self-mastery of former slaves, but the unconditional victory of the slave and a kind of slavish morality. The typical citizen of a liberal democracy was a “last man” who, schooled by the founders of modern liberalism, gave up prideful belief in his or her own superior worth in favour of comfortable self-preservation. Liberal democracy produced “men without chests,” composed of desire and reason but lacking thymos, clever at finding new ways to satisfy a host of petty wants through the calculation of long-term self-interest. The last man had no desire to be recognised as greater than others, and without such desire no excellence or achievement was possible. Content with his happiness and unable to feel any sense of shame for being unable to rise above those wants, the last man ceased to be human.

Following Nietzsche’s line of thought, we are compelled to ask the following questions: Is not the man who is completely satisfied by nothing more than universal and equal recognition something less than a full human being, indeed, an object of contempt, a “last man” with neither striving nor aspiration? Is there not a side of the human personality that deliberately seeks out struggle, danger, risk, and daring, and will this side not remain unfulfilled by the “peace and prosperity” of contemporary liberal democracy? Does not the satisfaction of certain human beings depend on recognition that is inherently unequal? Indeed, does not the desire for unequal recognition constitute the basis of a livable life, not just for bygone aristocratic societies, but also in modern liberal democracies? Will not their future survival depend, to some extent, on the degree to which their citizens seek to be recognised not just as equal, but as superior to others? And might not the fear of becoming contemptible “last men” not lead men to assert themselves in new and unforeseen ways, even to the point of becoming once again bestial “first men” engaged in bloody prestige battles, this time with modern weapons?

This books seeks to address these questions. They arise naturally once we ask whether there is such a thing as progress, and whether we can construct a coherent and directional Universal History of mankind. Totalitarianisms of the Right and Left have kept us too busy to consider the latter question seriously for the better part of this century. But the fading of these totalitarianisms, as the century comes to an end, invites us to raise this old question one more time.

1 note

·

View note

Text

I never thought the piece of art that would most perfectly capture the complicated, loving, and fraught relationship between mothers and daughters with generational trauma would be a fucking d&d campaign about stoats and nuclear power plants.

Like at it’s core this is the story of exile, filled with all the generational trauma and grief that comes with it. In just seconds, they lost everything they’ve ever known but each other. They lost their childhood homes, their community, and their way of life. All to find that the thing they were taught to respect and thought was an offer of safety, was just secrets, control, and more danger than they’ve ever known.

People joked for years that Brennan made capitalism the big bad, and then Aabria turned around and went “what if we give communism a turn?”

#dimension 20#aabria iyengar#burrow's end#burrow’s end spoilers#d20#im going insane over it#it’s like someone snuck into the lunches my mom and I have with my abuela#Like I’m out here fighting for my life every time Erika gives me psychic damage#and maybe it’s just that I’ve been raised by a single mom as a Cuban American with a family that literally rebeled against a regime#but this is literally the best depiction of my family I think I’ve ever seen and I might actually lose my mind about it#anyway#d&d is fucking wild man#also aabria I know you go here and I’m so sorry if this comes across your dash#like idk where you’re going with this but fuck it’s incredible and thanks#also before anyone says anything captialism is an horror and I truly believe that the Last Bast could be beautiful#but my spidery senses and family history have me on the edge of my seat

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

when will this bloody exam be over with I want to go to uni already!! Good Lord

#[.txt]#looking over at my history course. At the monastery I'll be hosted in. At the medieval city I'll be moving to. Can it be september already.#I cannot emphasize enough how much i don't care about my final grade for this exam. 20% of it is math and my teacher was terrible#so it's not as if I can hope to get a good grade anyways! And the money prize is only for 110/100 marks so who cares about it going well.#I just want it gone and passed with a 60. Please. It's a useless exam in any case.#literally it was just made so private schools could give out the same qualifications and there has GOT to be a better way to do that.#OR. Or just have an exam at the end of each year. Why only on the last. man#tomorrow I have the essay (20%) and the day after math (another 20%) and my final interview for another 20% is on the fifth of July#and I already have a full 37/100 credits so I just need 23 points. Which between the essay and the interview I'm sure to get. let me outttt

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

/ What are the chances that a bat god would fall in love with (insert ur muses' name)-

#WHAT are the chances that the last emperor of the Byzantine empire would fall for (insert ur muses' name)#what are the chances that the god of the night sky; hurricanes; conflict; obsidian; sacrifice woums fall in love with (insert ur muse name)#what are the chances that one of the best warriors during the kurukshetra war would fall in love wit-#what are the chances that the king of ithaca who fought on the trojan war + embarked on a journey that seemed to have no end would#fall in love with (insert ur muses' name)#what are the chances that a bat god and (ur muses' title) would fall in love-#what are the chances that a man considered to be one of the most important rullers in wallachian history would fall in love with u rn-#I COULD GO LIKE THIS ENDLESSLY#im missing more but#basically; i wanna write pinning and romance and and-#im putting all of them on the table 😳

21 notes

·

View notes

Note

The Good Witch -> The Last One

Emily -> Will yeah?

AHHHHH WAIT OK OK???? YEAH HELLO???? inform you this is armageddon vs when the sky is filled with smoke I'm still the last to go??? and haunt a house nobody lives in vs wax wings in the back rooms with my arms out trying to catch you??? am I better yet vs lost cause in Levis but I'll always see great heights in you/if you're the Syd Barrett of the band I'm the one on the train tracks holding your hand!!!!!!! she doesn't have to be better she doesn't have to get better!!! he loves her anyway!!!!!!

#last one as a will song alone is life changing perhaps because it's SO TRUE#he IS the last one!!!! always!!!!#broke nose dumb smile that's my girl!#supernatural but british#absolutely losing it#sometimes the love is the end!!! sometimes the end of it isn't the history of man! sometimes the love is true!

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

I've been following that AITA blog for a bit now and it has me thinking about my own life situations with conflict and drama. A passive "do I have anything I could submit to that blog?" But upon thinking about it, it's like... I really find no value in asking strangers whether I'm "the asshole" in situations. There are situations where I'm clearly not at fault, situations where I was a little shit but it was justified, and at least one situation where I have a definite "Oh yeah, I was definitely the asshole there". All in the past, so it's not like I'd even need advice or anything. I already know, so what's the point?

Maybe it stems from me being a generally self-aware and self-confident kind of person. I know what's going on with myself, know when I've wronged people, & I have a mentality of "well, I'll try to not do that in the future." Even if I feel a little guilty thinking back, what's the point of asking after something when I know I'm at fault? Or situations where things were complicated and both people had fault in things, but I know I wasn't being shitty on purpose & that's what matters to me. Ultimately, it results in a bunch of strangers drawing conclusions about things I really don't care about outside input on.

Still love reading the blog tho. There's something about reading up on random people's life drama that satisfies that gossipmonger soul in me So well.

#speculation nation#i think the most blatantly YTA thing id get is when i ghosted that guy i was seeing back when i was 20 or so#wasnt ever actually dating but i made it sound like i would. very much led him on.#then realized i just wasnt into cishet guys At All and dropped him out of nowhere bc i was 20 and didnt know how to deal with feelings#objectively it was a pretty awful thing for me to do. and i feel bad that i did it.#have i ever tried to reach out and apologize tho? no lmao#it happened so long ago now i feel like itd bring more animosity than relief anyways.#id like to think ive learned from it tho. Dont Date People Just For The Hell Of It.#god it rly is my romantic history where im the biggest asshole. my prior girlfriend too#i do feel bad about that. i never meant to hurt her but that sure is what i did.#it was better to break it off when i did. wouldve been better had i did it earlier but oh well.#then as a teenager and my whole fucked up romance life then...#but NO LONGER!!!!!!!! hopefully lol. im rly into my current girlfriend and after my last one ive been dedicated to. not do that again.#cant date people just because im bored. that's never ended well for me.#i learned my lesson this time for SURE!!!!!#anyways yea id say more constently id be The Asshole in these situations. but im only human man it happens.#other situations it's usually just fucked up situations with me being a toxic little shit in response bc it's all i knew.#idk. community voting doesnt matter to me. learning from my prior mistakes and shortcomings is what matters to me.#it's interesting to see the blog tho. people are insecure about some of the most trivial things sometimes...

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

the ssum’s user interface is really depressing to me as someone who unfortunately took harry’s route very seriously

there are mysme calls that i still listen to sometimes even though i first played them six years ago. that archive is functional enough to allow that.

if i want to revisit ssum content in a few years, am i going to have to scroll through months and months of empty milky way calendars in order to do so?

#606.txt#cheritz please fix this i’m already insane enough#the ssum is even less replayable than mysme imo#so i don’t think that i’ll be restarting the route or part of it besides maybe the last ten days#like even now (a week after my save ended) it’s so sad to see the sky empty of stars when i scroll back to replay calls#am i too attached to a man who is pixels and lines? yeah#but that is… i would argue that is the intended experience of the game#idk it annoys me that there are 10000 stupid side quests in the game that add nothing but took time and thought and resources away from#designing the MAIN user interface#that sucks by the way#in every capacity#i hope they fix this in the next couple of years at least idk#i wish the ui was um#anything like mysmes#it’s so easy to find things in the history#vs the ssum you have to basically. remember the exact day it was

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

just when i was starting to think the guy was being kept immortal by the power of war crimes alone

#bee posts nonsense#i hadn't even managed yet to comprehend the fact that he was still alive i have no idea how my brain's going to keep up with this#in all seriousness i wonder if on some level he knew how history would end up judging him. or more interestingly if he cared#i don't think this year can handle any more historical events man#didn't he put out that statement last month after oct. 7th that somehow made it all about his thoughts on muslims in germany#which were... interesting thoughts to say the least#henry kissinger#us politics

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Last scene of all,

That ends this strange eventful history,

Is second childishness and mere oblivion;

Sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything.

~ William Shakespeare

#William Shakespeare#As You Like It#Jaques#Speech#All The World's A Stage#The Seven Ages of Man#last scene#ends#strange eventful history#second childishness#childishness#oblivion#Sans teeth#sans eyes#sans taste#sans everything#quote#quotes#poem#poetry#Saleh Badrah#Poetictouch

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

hannibal nbc is such a weird lil series when you considered that when it got aired, the trend in early 2010s tv shows are mostly detective series like csi, ncis, the blacklist etc

it's even hilarious when i'm reminded how hannibal did start like a proper crime thriller tv show at first, like i still remember when i watched the pilot on tv for the first time, i thought "hmm this looks like the other tv shows but damn they presented everything in such weird ways"

then season 2 aired.

like, season 2 really changed everything, i can't really call it a crime procedural tv series anymore at that point, it had already morphed into something hilariously very distinct from that first episode aired in 2013

#that's how it ended up identified as a lil gothic horror series instead now#but honestly this is the only thing you can experience if you followed the story right when the first episode aired#i know nothing. NOTHING about how it'll end#i still remember bawling my eyes out when i watched the last scene in season 1 episode 12#i really thought abigail is fucking DEAD#but yeah i love this tv show man it really fundamentally changed me as a person#hell it's one of the tv show that's able to survive the whole cancellation fiasco as streaming start to get popular#and able to tell its story in its entirety without sacrificing the quality of its presentation#the best fucking finale ever in american television history i would say#tmi tag

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

me after p9-12…

#ff.txt#ffxiv#ffxiv spoilers#ffxiv patch 6.4#ffxiv pandaemonium#I genuinely had a meltdown at the end#themis my beloved#never did I think I’d be an elidibus stan but here we are#I genuinely am going to miss him every single day#never not missing him#erichthonios too my heart is broken#literally this quest line is so precious to me#we were the trio of literal dungeon crawlers#my heart </3#I’m in shambles I literally couldn’t form coherent words after the last cutscene#my eyes were blurring with tears and my head still hurts#I’m so exhausted from that HHHH no regrets tho#p9-12 is so unbelievably fun#but man the story just tore me in half and stepped on my heart#ffxiv being one of the best written pieces of media in the history of forever

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dude I do love my pot.c s/i's look but I'm considering changing it up, maybe more as a change from movie to movie rather than a total change forever 🤔

#her outfit is iconic to me and i use it in a lot of my avatars online and stuff; it's easily recreatable in that way#like for my bitmoji and my steam picture uaing dis.ney dream.light valley#technically they have a different look for the last movie even tho i havent seen it ajfklds they're just older in that movie#and have a different outfit and haircut and stuff#but now im thinking that maybe her typical outfit and hairstyle will be for cot.bp#and i'll make her a new one for dead man's ch.est and maybe a whole other one for at worl.d's end#i'll consider one for on st.ranger tides too#i just reeeeeally like them and i wanna keep working on them ajfkdsl#but i dont wanna solidify history or anything yet; they're still kinda mysterious and i like that afjldks#ren speaks#s/i: ren sparrow#jackren

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

One more thing is that in game, M.octezuma takes on a new and different name which is 'i.zcalli' and I think that in the context of a Grail war, he could go by that instead of being called 'avenger' to conceal his true identity

#;ooc#ooc#its been some time since i finished l.b7 so i have to re-read it to confirm whether this was the case or im going delusional but#since in the story he's brought back to have a second chance in life; he takes on a new name#i think that in his case; having a new name isnt only to conceal his identity but its like a barrier to him#we see how the first time he sees the protagonist and company; he mentions how the scar in hia forehead hurts#so not going by his true name of m.octezuma it helps him repress the memories of his past#we also see how he imposes on himself the title of t.ezcatlipoca (or well the future t.ezcatlipoca) and tries to follow it to a T#so in a way he's running from himself in a lot of ways#its the regret; the guilt; the despair;#he's willing to discard his own identity in order to change the course of history; to change how things ended; for this last second chance#its why the class of avenger does quite fit him in this context#its a man who's haunted by his past; by how things went; its that kind of servant#like how j.eanne alter cant forgive; like how d.antes is stuck in a period of his life; how s.alieri is cursed by the narrative created-#around his figure; etc etc#i think m.octe is interesting bc of this; he truly goes through extremes; he takes any and every step he can without an ounce of hesitation#its blind and its desperate and even when he faces the other t.ezcatlipoca; he ends up betraying himself; and even the god he is supposed-#to become and follow#he s.hoots him; he k.ills him; its the first time there is hesitation in him; just for a moment#anyways i say he coukd go by i.zcalli in a grail war but#considering its the context of the l.b what gives him that name; it would probably be something else on a different reality

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

the end of chapter 2 WAS very cool and interesting. yelped when the ancestor said he received A Letter (THE LETTER?). i am going to be writhing every single day until the new chapter gets added and the story progressed

#i was a little eh :/ on his characterization initially but it does kind of feel like this is some Other aspect of the man. hes dead now--#--but the heart of darkness DID use him as a weird avatar thing so even beyond the strange of him maybe communicating after death who the--#--hell knows what that means. like a different asepct of the same man spoke to the heir who was dealing with atrocities which were--#--DIRECTLY the ancestors fault as opposed to the prodigy who has a canonical past with the man and is dealing w--#--what is essentially a natural disaster mass extinction event type thing. hes a more sympathetic figure#<-- is scholar the right title instead for the '''player character''' (VERY loose usage of that term) of dd2? idk#the scholar is slowly growing on me as well. weird cowardly academic who accidentally scoops up perhaps the most--#--qualified mercenaries to deal w the end of the world and would maybe get pummeled into a pulp if he mentioned the ancestor in a--#--casual light#like hes telling them abt the iron crown or whatever and says smth like 'oh my mentor [ancestor last name] and i' and immediately--#--every single mercenary side eyes each other HARD like um. did you hear what he just said. especially funny if the runaway is there too--#--and has no idea what is going on and why all of the other guys have twelve layers of history w each other#<-- i DO want to write smth playing w that concept. like maybe when the stagecoach travels thru the sluice or they encounter the--#--antiquarian or whatever just smth with the idea of her being an outsider and seeing+hearing all these things she has no context for#i really do want to like her but she does not have the stellar characterization and dialogue writing of the first game to prop--#--up the so far weak stuff of the second so it is SO hard to find anything of interest 😔

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

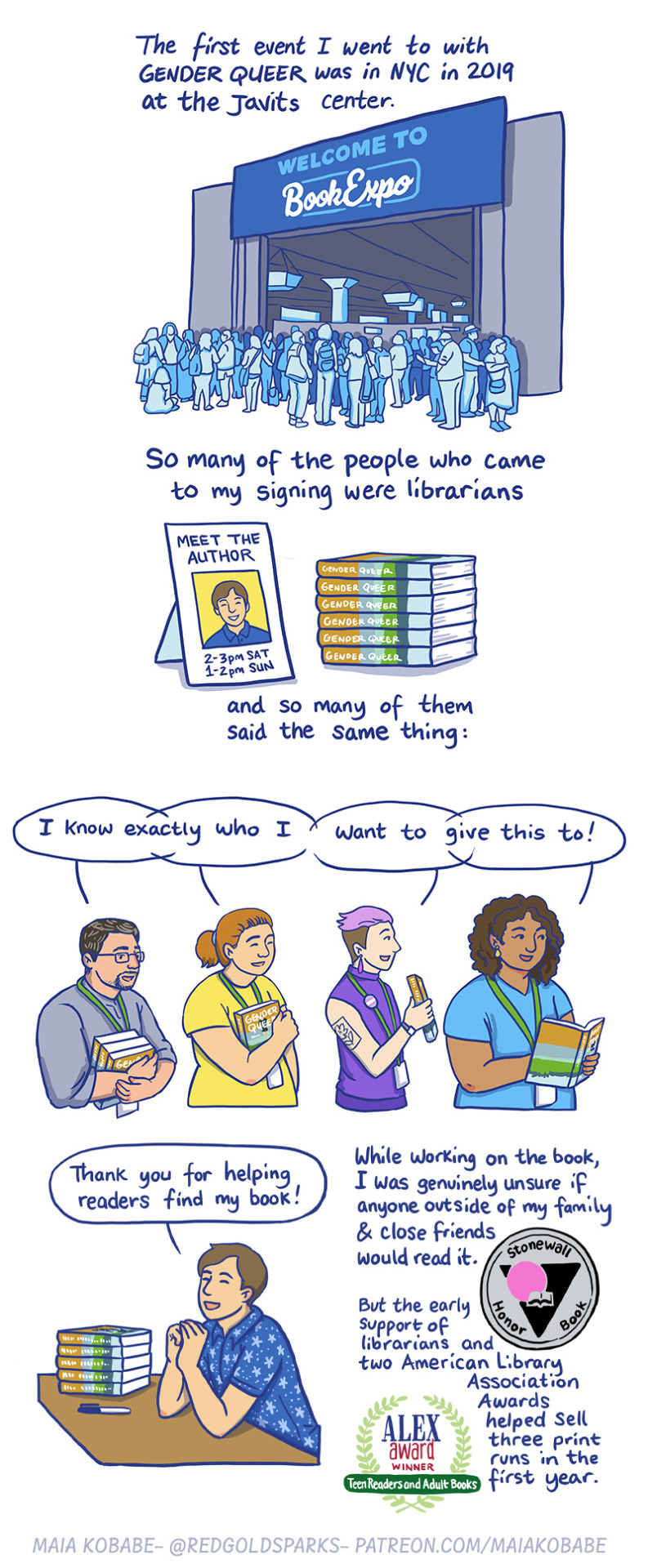

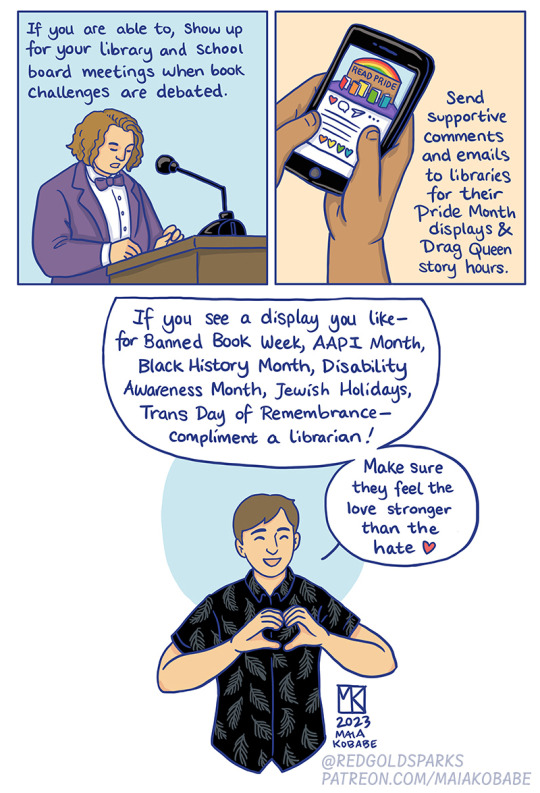

My very last comic for The Nib! End of an era! Transcription below the cut. instagram / patreon / portfolio / etsy / my book / redbubble

The first event I went to with GENDER QUEER was in NYC in 2019 at the Javits Center.

So many of the people who came to my signing were librarians, and so many of them said the same thing: "I know exactly who I want to give this to!"

Maia: "Thank you for helping readers find my book!"

While working on the book, I was genuinely unsure if anyone outside of my family and close friends would read it. But the early support of librarians and two American Library Association awards helped sell two print runs in first year.

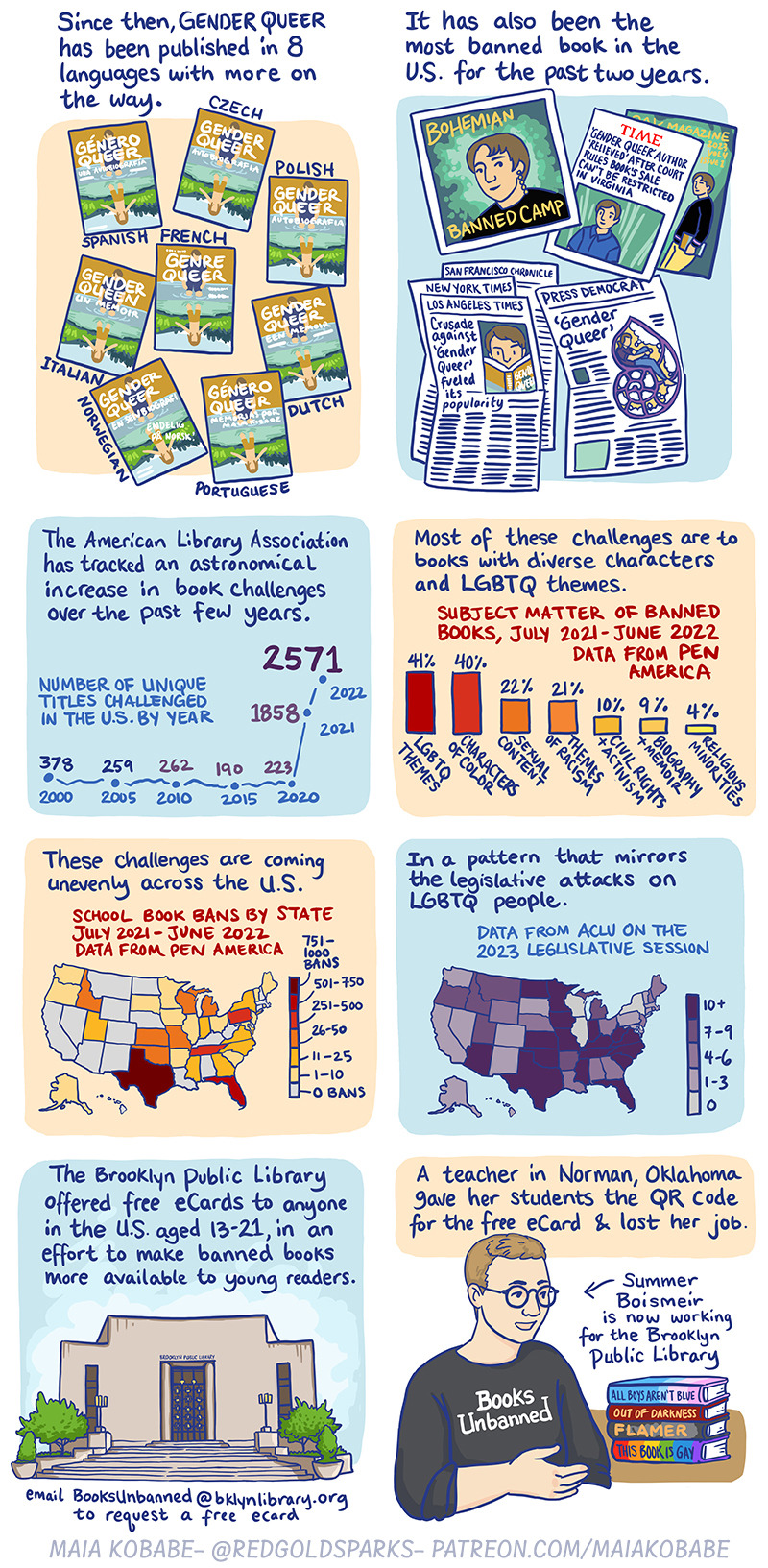

Since then, GENDER QUEER been published in 8 languages, with more on the way: Spanish, Czech, Polish, French, Italian, Norwegian, Portugese and Dutch.

It has also been the most banned book in the United States for the past two years.

The American Library Association has tracked an astronomical increase in book challenges over the past few years. Most of these challenges are to books with diverse characters and LGBTQ themes. These challenges are coming unevenly across the US, in a pattern that mirrors the legislative attacks on LGBTQ people.

The Brooklyn Public Library offered free eCards to anyone in the US aged 13-21, in an effort to make banned books more available to young readers. A teacher in Norman, Oklahoma gave her students the QR code for the free eCard and lost her job. Summer Boismeir is now working for the Brooklyn Public Library.

Hoopla and Libby/Overdrive, apps used to access digital library books, are now banned in Mississippi to anyone under 18. Some libraries won’t allow anyone under 18 to get any kind of library card without parental permission.

When librarians in Jamestown, Michigan refused to remove GENDER QUEER and several other books, the citizens of the town voted down the library’s funding in the fall 2022 election. Without funding, the library is due to close in mid-2024.

My first event since covid hit was the American Library Association conference in June 2022 in Washington, DC. Once again, the librarians in my signing line all had similar stories for me: “Your book was challenged in our district"

"It was returned to the shelf!"

"It was removed from the shelf..."

"It was moved to the adult section."

Over and over I said: "Thank you. Thank you for working so hard to keep my book in your library. I’m sorry you had to defend it, but thank you for trying, even if it didn't work."

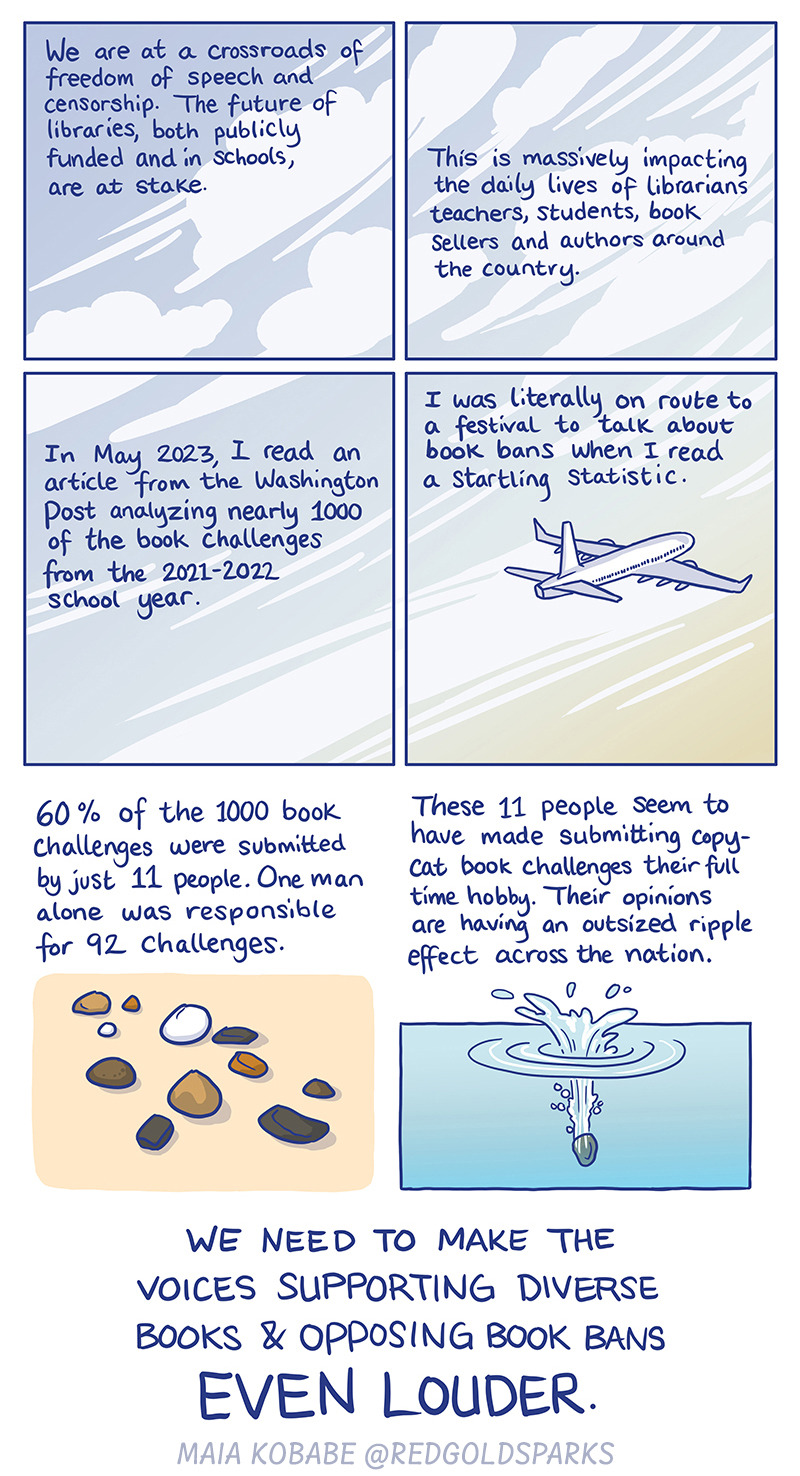

We are at a crossroads of freedom of speech and censorship. The future of libraries, both publicly funded and in schools, are at stake. This is massively impacting the daily lives of librarians, teachers, students, booksellers, and authors around the country. In May 2023, I read an article from the Washington Post analyzing nearly 1000 of the book challenges from the 2021-2022 school year. I was literally on route to a festival to talk about book bans when I read a startling statistic.

60% of the 1000 book challenges were submitted by just 11 people. One man alone was responsible for 92 challenges. These 11 people seem to have made submitting copy-cat book challenges their full-time hobby and their opinions are having an outsized ripple effect across the nation.

WE NEED TO MAKE THE VOICES SUPPORTING DIVERSE BOOKS AND OPPOSING BOOK BANS EVEN LOUDER.

If you are able too, show up for your library and school board meetings when book challenges are debated. Send supportive comments and emails about the Pride book display and Drag Queen story hours. If you see a display you like– for Banned Book Week, AAPI Month, Black History Month, Disability Awareness Month, Jewish holidays, Trans Day of Remembrance– compliment a librarian! Make sure they feel the love stronger than the hate <3

Maia Kobabe, 2023

The Nib

19K notes

·

View notes

Text

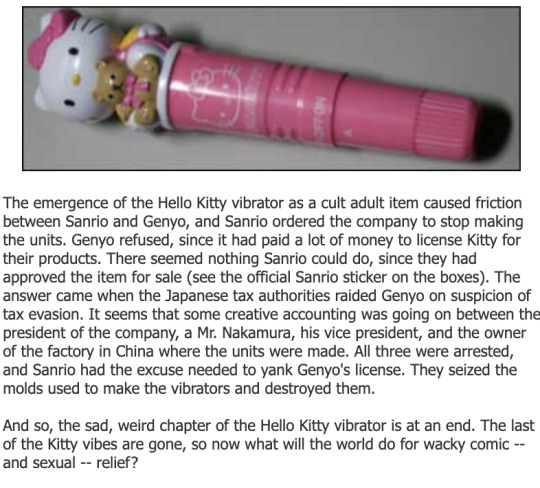

I found myself having, not exactly an argument recently, but a highly opinionated conversation with someone who did not believe my assertion that once upon a time there were official Hello Kitty vibrators. With the aid of the Wayback Machine, I found this article, and thought the world at large might enjoy it too...

Here's the text of the article:

The history of the Hello Kitty vibrator

By Peter Payne

October 4, 2004

Sanrio is one of the top character licensors in the world, having more or less created the business model of doing business by creating something that doesn't really exist and licensing its use to other companies. Sanrio produces nothing -- all their characters, like the Little Twin Star, Minna no Ta-bo, Bad Batz-Maru, exist as legal entities and nothing more. Their most successful character, Hello Kitty, or Kitty-chan as she's known in Japan, is now now thirty years old.

One of the many companies that license Sanrio's characters for their products was a Japanese company called Genyo Co. Ltd. Genyo made a wide variety of products, from bento boxes to children's toys to chopsticks, many with the Hello Kitty character on them. They scored big in the late 1990's with an off-the-wall hit, a series of Hello Kitty toys which featured a different Kitty figure from each of Japan's 47 prefectures, each representing something the prefecture was famous for. (The figure from Gunma Prefecture, where we live, represented a wooden kokeshi doll.)

In 1997, Genyo designed a product that would live in infamy: the Hello Kitty vibrating shoulder massager, which really is a shoulder massager (trust us -- it says so on the package). Sanrio approved this design without batting an eye, and the product enjoyed modest sales in toy shops and in family restaurants like Denny's and Coco's. It wasn't until 1999 or so that people began to catch on to the fact that the Hello Kitty massager had other potential uses, and with amazing speed, they started popping up in adult videos in Japan. The next thing anyone knew, they had changed into a cult adult item, sold in vending machines in love hotels -- after all, what self-respecting man wouldn't buy his girl a Hello Kitty vibrator when she asked him for one?

The emergence of the Hello Kitty vibrator as a cult adult item caused friction between Sanrio and Genyo, and Sanrio ordered the company to stop making the units. Genyo refused, since it had paid a lot of money to license Kitty for their products. There seemed nothing Sanrio could do, since they had approved the item for sale (see the official Sanrio sticker on the boxes). The answer came when the Japanese tax authorities raided Genyo on suspicion of tax evasion. It seems that some creative accounting was going on between the president of the company, a Mr. Nakamura, his vice president, and the owner of the factory in China where the units were made. All three were arrested, and Sanrio had the excuse needed to yank Genyo's license. They seized the molds used to make the vibrators and destroyed them.

And so, the sad, weird chapter of the Hello Kitty vibrator is at an end. The last of the Kitty vibes are gone, so now what will the world do for wacky comic -- and sexual -- relief?

44K notes

·

View notes