#the international buster Keaton society

Text

This Day in Buster…March 30, 1924

The Chicago Tribune prints a reader’s poem, the first stanza being devoted to our Buster: “Buster Keaton, why don’t you smile? And why do you look so glum? Is it just your cynicism, Or are you really dumb?”

#this day in buster#buster keaton#poem#1920s#silent era#silent movies#vintage hollywood#ibks#the international buster keaton society#buster keaton society#the damfinos#damfino#damfamily

86 notes

·

View notes

Text

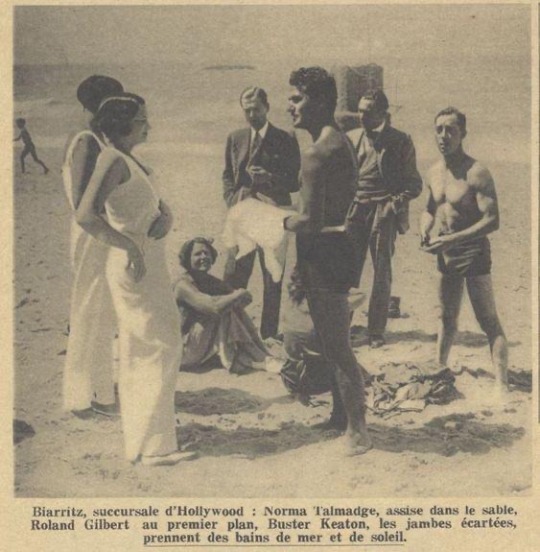

In case of Bad day, gaze at shirtless buster.

#buster keaton#busterkeaton#gilbert roland#Beach#swimwear#shirtless#muscles#beachwear#the international buster keaton society

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

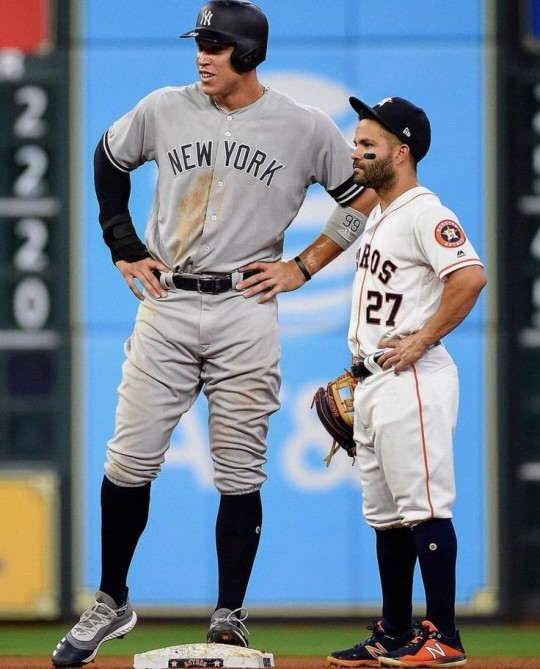

Does Buster Keaton count as a short king?

#busterkeaton#buster keaton#buster#busterkeatonsociety#buster keaton fandom#the international buster keaton society#short king

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

My Membership Card & Pin arrived in record time - just over a week from the US to the UK! How many more Damfinos are reading this?

#buster keaton#the great stoneface#damfino#the international buster keaton society#busterkeaton.org#membership#pork pie#one week#pin#I feel like that pin represents the disaster that is 2020

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jose Altuve of the Houston Astros. The Buster Keaton of MLB. Both are 5"5'.

#buster keaton#ibks#international buster keaton society#baseball#mlb#jose altuve#houston astros#5"5'

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Sixth Annual Buster Keaton Blogathon

The Sixth Annual Buster Keaton Blogathon

Reprinted from Silent-ology website

I am a big fan of the Silent-ology site and as such, I am doing a down and out PLUG for the upcoming Blogathon!

Please click on the link to her website for the whole entire post!

When: Monday, March 9 and Tuesday, March 10, 2020.

Where: Right here on Silent-ology!

How: To join in, please leave me a comment on this post and let me know which…

View On WordPress

#Blogathon#Buster Keaton#Comedy#International Buster Keaton Society#Keaton Society#Official Sponsor#Patricia Tobias#Silent Films#Silent-ology#Surreal Joy#Vaudevisuals

0 notes

Text

More movies (and a tv series) on youtube to keep you busy

List 1 / List 2

Here’s a third update of movies that you can watch in full on youtube since you’re stuck inside

Documentaries about movies:

Visions of Light: The Art of Cinematography (1992): Featuring interviews with more than two dozen major cinematographers and a ton of clips, this is a useful and enjoyable primer for anyone interested in learning what a DoP does

Vittorio Storaro: Writing With Light (1992): This is a shorter (40 minute) television doc focusing on one specific cinematographer, Vittorio Storaro, famed for his collaborations with Bertolucci and for shooting Hollywood movies like Apocalypse Now and Reds

The Epic That Never Was (1965): In 1937, Josef Von Sternberg started shooting an adaptation of I, Claudius starring Charles Laughton as Claudius. Dirk Boagarde hosts this lively documentary examining why the film was never completed, featuring the surviving footage from the 1937 shoot.

Hollywood: A Celebration of the American Silent Film (1980): Kevin Brownlow and David Gill’s 13-episode miniseries about the silent film era is considered the gold standard for documentaries about film history, but the impossibility of negotiating the rights to all the clips used at a reasonable price has kept it off of dvd or blu-ray. Luckily, that didn’t stop someone from putting it on youtube, although episode 12 has in fact been blocked due to a copyright claim.

Buster Keaton: A Hard Act To Follow (1987) Part 1 / Part 2 / Part 3: Another Kevin Brownlow and David Gill miniseries, this one, as you’ve probably guessed, covers the life and films of Buster Keaton over three episodes.

More movies:

Powell/Pressburger: Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, aka the Archers, were one of the greatest writer/director teams in film history (and a favorite of Scorsese, who seemingly made it his life’s mission to ensure that their films were restored and available), and three of their incredibly charming, magical movies are on youtube. Of the available ones, I Know Where I’m Going! is probably the best to start with.

I Know Where I’m Going! (1945): Dave Kehr on the film: “Michael Powell's 1945 film resists easy classification: it opens as a screwball comedy, grows into a mystical, Flaherty-like study of man against the elements, and concludes as a warm romance. Wendy Hiller, in one of the best roles the movies gave her, is a toughened, materialistic young woman on her way to meet her millionaire fiance in the Hebrides; Roger Livesey is the young man she meets when a storm blows up and prevents her crossing to the islands. Funny and stirring, in quite unpredictable ways, with the usual Powellian flair for drawing the universal out of the screamingly eccentric.”

A Canterbury Tale (1944): The Criterion jacket copy: “Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s beloved classic A Canterbury Tale is a profoundly personal journey to Powell’s bucolic birthplace of Kent, England. Set amid the tumult of the Second World War, yet with a rhythm as delicate as a lullaby, the film follows three modern-day incarnations of Chaucer’s pilgrims—a melancholy “landgirl,” a plainspoken American GI, and a resourceful British sergeant—who are waylaid in the English countryside en route to the mythical town and forced to solve a bizarre village crime. Building to a majestic climax that ranks as one of the filmmaking duo’s finest achievements, the dazzling A Canterbury Tale has acquired a following of devotees passionate enough to qualify as pilgrims themselves.”

Gone To Earth (1950): Made under unhappy circumstances (David O. Selznick producing), this is a gorgeous technicolor romance starring Jennifer Jones as a nature loving young woman forced into a choice between two “civilized” men, with tragic results.

Straub/Huillet: If you’re looking for something easy and relaxing to watch during the quarantine, I’d recommend literally anything else other than the films of Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet. J. Hoberman on the couple: “Straub-Huillet, as they preferred to be called, are cinema’s conscience — an antidote to all the junk movies you’ve ever seen. Drawing on Kafka, Cézanne, Brecht, Schoenberg and Malraux, to name only some of their best-known sources, Straub-Huillet films are meant to raise ethical questions on subjects as varied as proper camera placement and the appropriate political approach to the subject.“We make our films so that audiences can walk out of them,” Mr. Straub once said, perhaps not altogether in jest.” Of the available ones, Class Relations, their adaptation of Kafka’s unfinished novel Amerika, seems to be agreed upon as the easiest place to start as it’s the closest to a straightforward narrative, although History Lessons has also been recommended as a relatively easy starting place by some people. Not Reconciled, which compresses an epic Heinrich Boll novel following three generations throughout multiple timelines into 52-minutes, is not recommended to start with. MUBI did a retrospective of their works and had essays commissioned for each one to help viewers out so I’ll link those with each film. Hit Closed Captions for subtitles.

Not Reconciled (1965): Here’s a 10-minute video essay by critic Richard Brody that will help you have a slightly easier time with Not Reconciled if you decide to give it a try. Here’s the MUBI essay

Othon (1970): In the 17th century Pierre Corneille wrote Othon, set in ancient Rome. Straub-Huillet’s adaptation is shot in the actual ruins of Roman palaces with modern buildings and cars visible in the background. The MUBI essay

History Lessons (1972): An adaptation of Bertolt Brecht’s The Business Affairs of Julius Caesar. From the MUBI essay: “In the film, an unnamed young man tours Rome and conducts interviews with toga-clad members of ancient Roman society on the subject of “C,” meaning of course Julius Caesar. It plays like Citizen Kane shorn of any of the flashbacks that bulk out that film: here, it is all exposition, reminisces, impressions. Interspersed through these sedentary discussions are a series of randomly protracted car rides through the city, all recorded in unbroken takes from the backseat of the young man’s Fiat 500.From this brief description alone, I’m sure you can see why structuralist-minded academics in the seventies had a field day.“

Fortini/Canti (1976): From the MUBI essay: “In Fortini/Canti, the Italian Communist writer Franco Fortini reads aloud from his Dogs of the Sinai (only recently translated into English for the first time), a memoir of his life as an Italian Jew and an extended reflection on the aftermath of the Third Arab–Israeli War of 1967 and its representation in the Italian media and by the political class. [...] Like all of Straub-Huillet’s movies, this astonishingly combative film follows an internal rhythm born out of the particulars of landscape, of speech, and of the physiognomies of its actors. It begins with an extended recording of a television newscast about Israel/Palestine (thus distancing the audience from the warped words and images on screen), a quotation from Fortini that connects like a punch in the jaw (“People don’t like having to change their minds. When they have to, they do so in secret. The certainty of having been tricked turns into cynicism. Gain for the cause of conservatism”), and then alternates between short jabs like these and more sustained verbal and visual attacks.”

Too Early/Too Late (1982): Serge Daney on the film: “No actors, not even characters. If there is an actor in TOO EARLY, TOO LATE, it’s the landscape. This actor has a text to recite: History, of which it is the living witness. The actor performs with a certain amount of talent: the cloud that passes, a breaking loose of birds, a break in the clouds; this is what the landscape’s performance consists of. This kind of performing is meteorological. One hasn’t seen anything like it for quite some time. Since the silent period, to be precise.” The MUBI essay

Class Relations (1984): The aforementioned adaptation of Kafka’s Amerika, often recommended as a place to start with Straub/Huillet. The MUBI essay

Hitchcock: Back to fun stuff, three Hitchcock classics.

The 39 Steps (1935): Dave Kehr: “As an artist, Alfred Hitchcock surpassed this early achievement many times in his career, but for sheer entertainment value it still stands in the forefront of his work.“

Shadow of a Doubt (1943): Kehr again: “Alfred Hitchcock’s first indisputable masterpiece. . . . Hitchcock’s discovery of darkness within the heart of small-town America remains one of his most harrowing films, a peek behind the facade of security that reveals loneliness, despair, and death. Thornton Wilder collaborated on the script; it’s Our Town turned inside out.“

Spellbound (1945): No one would argue it’s Hitchcock’s best and the psychoanalysis is very dated but with Gregory Peck, Ingrid Bergman, and Dali-designed dream sequences there’s still enjoyment to be had.

Ozu: One of Japan’s most beloved and revered filmmakers, he’s primarily known for his post-WWII family dramas, but his career stretched back to the silent era (although most of his silent films are lost). I Was Born But... is a good place to start but it’s not representative of the style he’s known for. Late Spring is where his later style fully emerges, and it’s a good place to start, so you might want to go in chronological order with these (Tokyo Story, widely considered one of the greatest films of all time, is also not a bad place to start).

I Was Born But... (1932): Jonathan Rosenbaum on the film: “One of Yasujiro Ozu's most sublime films, this late Japanese silent describes the tragicomic disillusionment of two middle-class boys who see their father demean himself by groveling in front of his employer; it starts off as a hilarious comedy and gradually becomes darker. Ozu's understanding of his characters and their social milieu is so profound and his visual style—which was much less austere and more obviously expressive during his silent period—so compelling that the film carries one along more dynamically than many of the director's sound classics. Though regarded in Japan mainly as a conservative director, Ozu was a trenchant social critic throughout his career, and the devastating understanding of social context that he shows here is full of radical implications.“

The Only Son (1936): Criterion’s jacket copy: “Yasujiro Ozu’s first talkie, the uncommonly poignant The Only Son is among the Japanese director’s greatest works. In its simple story about a good-natured mother who gives up everything to ensure her son’s education and future, Ozu touches on universal themes of sacrifice, family, love, and disappointment. Spanning many years, The Only Son is a family portrait in miniature, shot and edited with its maker’s customary exquisite control.”

Late Spring (1949): Ignatiy Vishnevetsky: “Each shot in Late Spring is striking on its own; the mature Ozu belongs to that rare category of filmmakers whose work can be recognized from a single frame. But together—with all their abrupt shifts in visual perspective and time—they become a mosaic, deeply poignant and ultimately mysterious in the way it envisions a relationship between two people trapped by how much they care for one another. There are domestic dramas, and then there’s this.“

Tokyo Story (1953): Dave Kehr: “The film that introduced Yasujiro Ozu, one of Japan's greatest filmmakers, to American audiences (1953). The camera remains stationary throughout this delicate study of conflicting generations in a modern Japanese family, save for one heartbreaking moment when Ozu tracks around a corner to discover the grandparents, alone and forgotten. A masterpiece, minimalist cinema at its finest and most complex.“

Early Spring (1956): Ozu on the film: “I wanted to portray the life of a white-collar man — his happiness over graduating and becoming a member of society. His hopes for the future when he got his job have gradually dissolved and he realizes that, even though he has worked for years, he has accomplished nothing worth talking about. By delineating his life over a period of time, I wanted to portray what you might call the pathos of the white-collar life...I tried to avoid anything that would be dramatic and to accumulate only casual scenes of everyday life in hopes that the audience would feel the sadness of that kind of life”

Equinox Flower (1958): Vincent Canby: “One of Ozu's least dark comedies, which is not to say that it's carefree, but, rather, that it's gentle and amused in the way that it acknowledges time's passage, the changing of values and the adjustments that must be made between generations.“

Late Autumn (1960): Peter Bradshaw: “Another gem from the Ozu canon, a masterpiece of tendernesss and serio-comic charm, as tonally ambiguous and morally complex as anything he ever made.“

And the tv series:

The Armando Iannucci Shows: You may know Armando Iannucci from his films, In The Loop and The Death of Stalin, or from some of his other television shows like The Thick of It or Veep, or from his involvement in all the Alan Partridge series with Steve Coogan. You probably missed The Armando Iannucci shows, his stream of consciousness sketch comedy that ran for one season back in 2001 (it didn’t help that it debuted in September of 2001), but it’s probably the most purely funny thing he’s ever done.

372 notes

·

View notes

Link

I want to do something for this but I can’t think of anything that would require money I don’t have

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

#SaturdayCaptions Caption this rare shot of a Buster Keaton smile, taken on the set of “The Silent Partner,” 1955.

#saturday captions#buster keaton#smile#1950s#vintage television#the silent partner#ibks#the international buster keaton society#buster keaton society#the damfinos#damfino#damfamily#caption this

29 notes

·

View notes

Photo

On Buster's Television Work

Even more ephemeral than silent film, most early television is lost to time. Buster Keaton is one of the silent film lucky ones in having his personal silent film work practically complete (with the exception of Roscoe Arbuckle’s Our Country Hero (1917) sadly still missing). His television work is another matter. Most of his television work of the 50s and 60s is lost. It's a shame since his wife Eleanor Keaton in Oliver Lindsey Scott’s The Little Iron Man states that Buster made about $55,000 per year from his television work in the 1950s. That’s well over $500,000 per year in 2017 dollars!

What we know is that starting with his appearance on The Ed Wynn Show in 1949 where he reenacted the molasses sketch from his first short movie appearance in The Butcher Boy (1917), Buster was in high demand. The new medium of television was hungry for actors ready, willing and able to handle the constant demand for material. And Buster was hungry for an audience again. Working in MGM’s backlot as a comedy fixer, consultant and writer, he had not thought there would be demand for his "type" of comedy again. Television was only too willing to oblige.

Many people do not realize it but after The Ed Wynn Show, Buster was given his own live show in December 1949 in Los Angeles:The Buster Keaton Show. With no nationwide cable transmission at the time, his show was only seen in the Los Angeles area. Apparently recording (kinescope) of the shows did not occur (except for one*). Buster did 16 episodes that do not even have accurate descriptions today! But these opened a flood gate of demand for his comedic services on television. Not only did he follow up his live show with another show, this time a filmed show of ~13 episodes, he appeared on talk shows, variety shows and even did dramas. (His listing on IMDB does not record all his television work!).

Buster’s comedy remained true to his comedic style. His shows were Intensely physical (stunningly so) and his comedy bits were mostly silent. Some sketches were rehashes from his silents, some were new. You can see his preference for his comedy of proportion (this time instead of Joe Roberts and Buster, it’s the pairing of a Hollywood “glamazon” and Buster!) and dream sequences. Never the shy one in his comedy, there’s always an opportunity for him to either appear in drag or dressed in furs. His comedy is so physically intense that you can see him huffing and puffing and catching his breath in the one recorded live Buster Keaton show.

He still consulted for a while behind the scenes of movies and even helped others behind the scenes on their TV shows. He was so popular that television stations also reached back and broadcasted his talking shorts from the 30s and showed an occasional silent. But the most remarkable aspect of his work and appearances on television during this period is the breadth of it. For instance, in 1950 he appeared on Los Angeles stations 24 weeks out of the year and New York stations for 16. In 1951, Los Angeles 23 weeks and NY 18. In 1952, LA 18, NY 26. Sometimes appearing at the same time, different shows, different coasts!

This pace would continue for the next 15 years. Interspersed with a few trips to Europe (working!), movies, theater productions, state fairs and TV commercials and you have an entertainer who was incredibly busy! Buster Keaton is an entertainer whose work didn’t end with with film’s silent era, nor with film’s early talking era of the 30s. His work continued substantially into the 50s and 60s - on television!

Stay tuned for more BK television updates.

* Amazingly one kinescope of Buster’s original live Los Angeles show has surfaced within the last few years. It can be seen on The Internet Archive.

- With thanks to The International Buster Keaton Society Inc who I’m proud to say has supported the ongoing research of Buster’s television work with a Porkpie Scholar Grant!

- With thankful encouragement from @catsandjammer and @bussielove and the whole Buster community on tumblr.

- This post is part of (@silent-ology) Silent-ology’s 3rd Annual Buster Keaton Blogathon commemorating the 100th anniversary since Buster entered the movies.

#buster keaton#television#television work#buster keaton blogathon#bk100#silent-ology#international buster keaton society#porkpie scholar grant#buster keaton blogathan pic#the buster keaton show#the gymnasium story#the detective story#the time machine#the billboard story#the theater story#buster in drag#princess rajah#eleanor keaton#buster keaton blogathon pic

168 notes

·

View notes

Text

Keatonesque

Last weekend The international Buster Keaton Society made a pretty cool announcement on their FB-page. In their newest revision The Oxford English Dictionary officially recorded ‘Keatonesque’ as a word in the English language! As part of some hundred newly added cinema-related words, Buster Keaton could not be omitted.

‘Keatonesque’, they say, typically refers to Keaton’s famous deadpan expression and penchant for physical comedy.

Isn’t it wonderful. To think: to be so very special and unique and unforgettable that you not only keep influencing your own craft long after you’re gone, but that you add to other fields as well! To become a word that’s deemed important in it’s own right.

Well now that Buster is a word, let’s try to use it a lot!

Let’s hope that in ten years time parents will say their children played so cute and keatonesque on the playground. Or that recipes add that whisking eggs is best done keatonesque. Or... Wouldn’t the whole world be a bit better off, if everyone was just a touch more keatonesque?

#buster keaton#keatonesque#he really changed the world#i'm proud#stuntman skills#and tbh in my dictionary this word means a great deal more

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Charlie Chaplin in Moscow

Early Soviet filmmakers took great inspiration from Charlie Chaplin, but his critique of mass production put him at odds with them.

In Charlie Chaplin’s 1914 film The Fatal Mallet, you can see “IWW” chalked on a wall in the background. While no one knows if the director — who grew up in south London’s slums and became a globally recognized comedian — supported the Wobblies at the time, we do know that the characters he played in dozens of short films in the 1910s and early 1920s would have.

In The Adventurer, he plays an escaped convict; in Police, an ex-con forced into burglary by unemployment; in The Bank, a janitor working next to, but unable to get ahold of, money; in Work, a downtrodden contractor; in The Immigrant, a migrant so frustrated by his treatment he kicks an immigration officer; and, of course, in The Tramp, a homeless man looking for a stable life. All these men, who populated the rapidly changing, expanding, and radicalizing United States, might well have written IWW on a fence in Los Angeles.

Chaplin wouldn’t state his politics explicitly until well into the 1930s, a move that would put him in the House Committee on Un-American Activities’ crosshairs. But in the aftermath of the Russian Revolution, young Soviet artists, designers, and filmmakers already thought they knew exactly what his politics were.

In 1922, the new Moscow magazine Kino-Fot, edited by the constructivist theorist and committed Communist Aleksei Gan, published a special issue on Chaplin. Throughout, painter and designer Varvara Stepanova depicted the actor as an abstract object, his body’s parts transformed into exploded shards and flying polygons, identifiable only thanks to his trademark hat, cane, and moustache.

Aleksandr Rodchenko’s text declares, manifesto-style:

[Charlie’s] colossal rise is precisely and clearly — the result of a keen sense of the present day: of war, revolution, Communism.

Every master-inventor is inspired to invent by new events and demands.

Who is it today?

Lenin and technology.

The one and the other are foundations of his work.

This is the new man designed — a master of details, that is, the future anyman.

That same year in Petrograd, teenagers Grigori Kozintsev, Leonid Trauberg, and Sergei Yutkevich, who collectively called themselves The Factory of the Eccentric Actor (FEKS), published something called “The Eccentric Manifesto.” Under the sign of “Charlie’s arse,” they demanded:

ART AS AN INEXHAUSTIBLE BATTERING RAM SHATTERING THE WALLS OF CUSTOM AND DOGMA. But we have our forerunners! They are: the geniuses who created the posters for cinema, circus, and variety theatres, the unknown authors of dust jackets for adventure stories about kings, detectives, and adventurers; like the clown’s grimace, we spurn your High Art as if it were an elasticated trampoline in order to perfect our own intrepid salto of Eccentrism!

Meanwhile, a film director was perfecting a technique that would eventually bear his name: the Kuleshov effect, in which the juxtaposition of unrelated material creates a new mental link between them. He argued against slow paced, European montage, which treats cinema as a high art form akin to theater, and for the high-speed American montage that thrilled audiences.

Somehow, these people, all trying to create art in the young Soviet Union, agreed that Chaplin represented their ideal. In a series of theatrical productions and films over the next decade, they would try to make something that had the same effect on their viewers — a socialist, avant-garde slapstick comedy, informed by silent farce, technological romanticism, and contempt for high culture.

This history sits a little strangely with what many know about the Soviet Union’s first fifteen years of experimental filmmaking. Its directors, including Sergei Eisenstein, Lev Kuleshov, and Vsevelod Pudovkin as well as documentary pioneers like Dziga Vertov and Esther Shub, have earned formidable reputation for applying Marxist methodology to film.

Their contributions, including “the montage of attractions,” the “camera eye,” the “intellectual montage,” and the aforementioned Kuleshov effect, have grounded film curricula since the 1960s, often used in contrast to Hollywood’s formulaic spectacles. In fact, when French filmmaker Jean Luc-Godard stopped making crowd-pleasers in the 1960s and opted instead for punishing Althusserian didactic tableaux, he signed his films Dziga Vertov Group.

What this story leaves out is how Soviet directors’ ideas came out of their obsessions with the crassest and most lurid kinds of American film, its chases, special effects, and pratfalls. In translating Chaplin for Lenin, they combined these elements with their equally strong interest in another aspect of 1910s America: scientific management and industrial efficiency, especially the work of Frederick Winslow Taylor and Henry Ford.

The resulting films shared a bizarre and unstable comic Americanism, which you can see still in films like Kuleshov’s Adventurers of Mr West in the Land of the Bolsheviks, a high-speed, Keystone Kops satire about Western perceptions of the Soviet state; Boris Barnet’s Miss Mend, where an international communist secret society foils the evil plans of nefarious capitalists; Sergei Komarov’s A Kiss For Mary Pickford and Pudovkin’s Chess Fever, which used footage of American stars on Soviet visits and put them into new, bizarre farces; and Eisenstein’s first feature, Strike, where insurgent workers move with all the bounce and assurance of a mass circus troupe.

Stage director Vsevelod Meyerhold helped pioneer this style. From the early 1920s onwards, he developed a “biomechanical theater” that borrowed equally from the circus’s high-wire tricks and gymnastic leaps, from Charlie Chaplin’s and Buster Keaton’s jerky, ironic slapstick, and from the USSR’s development of Taylorism, led by government-sponsored think tanks like the League of Time and the Central Institute of Labor. The latter’s founder, Aleksei Gastev, a former metalworker, union leader, and poet, became a key figure for most of the 1920s avant-garde.

Looked at coldly, his ideas are unnerving and dystopian. He imagined the new Soviet working class as nameless machines working in seamless unified motion, a somewhat unlikely and wholly unfulfilled demand of the chaotic, largely rural, and unskilled labor force of the Soviet 1920s. Yet while Taylorism involved monitoring the worker’s motions to transform them into a predictable, high-performance cogs, Meyerhold’s biomechanics saw its protagonists as Chaplin-like comic machines, capable of humor and exuberance, not drab labor.

This appears even more strongly in another form of Soviet Chaplinism, which comes from an unlikely direction — formalist literary criticism. The great Viktor Shklovsky used Chaplin as an exemplar of his concept of “ostranienie” or “making-strange.” In his 1922 Literature and Cinematography, he tried to work out what set Chaplin apart from other actors, finally deciding that “the fact that [the movement] it is mechanized” makes it so funny.

In the American context, Chaplin was satirizing industrial, mass-production labor, but in the Soviet landscape — destroyed by seven years of war and economic collapse — the little tramp who moved with jerky assurance through a mechanized world was exactly the sort of “new man” they needed.

American visitors found this all disconcerting. The sympathetic artist Louis Lozowick had to explain to eager young constructivists in Moscow that he didn’t know anything about biomechanics, and that they, the Russians, had invented it themselves. A Ford Motor Company representative, treated by his hosts to some biomechanical theater, thought the whole thing ridiculous and farcical.

In the mid-1920s, the Soviet Eccentrists would move away from the leaps, special effects, and extravagant silliness of movies like The Adventures of Mr West and develop a more sober style, although equally indebted to the frantic pace of American montage and cartoonish American acting styles. The results, such as Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin and Pudovkin’s Mother, had a mixed reception in the USSR but became international sensations. Their kinetic action sequences changed cinema history, and their rousing revolutionary narratives got them banned across the free world.

This is when Charlie Chaplin first became aware of his Soviet fan club. He opposed the bans and helped get these films shown to American audiences. When Eisenstein made an abortive attempt to film Dreiser’s American Tragedy in Hollywood, the two directors became fast friends. But the Soviet film director who had the strongest effect on Chaplin — whose feature films like The Gold Rush and City Lights had become ever more sophisticated and socially critical — was Eisenstein’s great adversary, Dziga Vertov.

A groundbreaking documentarian, Vertov thought fictional films were inherently bourgeois and escapist. Nevertheless, his special effects, comic juxtapositions, and pounding sense of rhythm made him an Americanist in his own way. In 1930, he made the first Soviet sound film, Enthusiasm — Symphony of the Donbas. This hour of grueling industrial propaganda doesn’t much resemble The Fatal Mallet. It depicts mechanizing the Donets coalfield in Eastern Ukraine and teaching the mineworkers Taylorist efficiency.

Chaplin, however, was attracted to the unrivalled intensity of its juxtaposition of sound and image. Using field recordings from Ukraine’s mines and steelworks, Vertov created an industrial jazz of still-astonishing power, a relentless clanging pulse echoing that puts the soundtrack closer to Einsturzende Neubauten than to Al Jolson. Chaplin called it “one of the most exhilarating symphonies I have ever heard.”

Six years later, he made his response. Modern Times has become justly famous for its definitive critique of Taylorism and Fordism. In the factory sequences, machines feed Chaplin, his all-seeing boss monitors him on film, and the production line eventually eats him, until he floats, weightless, through the cogs inside, a tragic and bitter image of the smooth and seamless mechanized labor the Soviets longed for. Insisting on keeping the film wordless, Chaplin used a soundtrack of rhythmic clangs and crashes that mirrored Vertov’s “Donbas” symphony.

Coming when Taylorist speed-up was sparking some of the greatest strikes in American history — not to mention the CIO’s formation — you might expect that the Soviets welcomed the film as a critique of American capitalism’s brutality.

They didn’t. In a text called “Charlie the Kid,” Eisenstein criticized his friend for his satire’s infantilizing and utopic take on what mass production does to workers. Regarding the factory sequence, he asserted, “At our end of the world, we do not escape from reality to fairy-tale, we make fairy-tales real.”

The tramp of Modern Times, exhausted by labor and made homeless by unemployment, accidentally picks up a red flag midway through a strike, getting him arrested as a dangerous agitator. Chaplin himself would be notably supportive of the Soviet Union, and his refusal to fall in with McCarthyism was admirable; but the tramp might have silently held other opinions about industrial efficiency and five-year plans than those he helped inspire.

0 notes

Text

The Buster Keaton Porkpie Scholar Grant

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

The International Buster Keaton Society is now accepting submissions for the 2017 Porkpie Scholar Grant.

2017 Deadline: Grant applications are due online Dec. 15, 2017.

The Porkpie Scholar Grant Program was established in 2008 with a substantial gift from a member of the International Buster Keaton Society who wishes to remain anonymous. The organization matched that gift to create the seed money for this grant program, which offers grants to authors, artists, film preservationists, filmmakers, composers and others who are contributing to the ongoing understanding and appreciation of the life and work of comedian/filmmaker Buster Keaton.

The International Buster Keaton Society, Inc., was founded in 1992 with the purpose of fostering understanding and perpetuating appreciation of the life, career and films of Buster Keaton. The group advocates for historical accuracy about Keaton’s life and work, encourages dissemination of information and research about Keaton, and endorses preservation and restoration of Keaton’s films and performances. The International Buster Keaton Society Porkpie Scholar Grant Program issues grants of $350 annually to one or two recipients (“Porkpie Scholars”) per year.

Eligibility: Grant projects should relate in some shape or form to the goals of the International Buster Keaton Society. Types of projects may include (but are not restricted to): articles or books, film restoration, musical scores, documentary films about Keaton, plays and art exhibits.

Application Process: Applications can be requested by email at [email protected].

22 notes

·

View notes

Photo

One of the giants of silent cinema, Buster Keaton, right, and his wife Natalie Talmadge, pose for a photo as they pass through Chicago on Sept. 27, 1922. ⠀⠀ ⠀⠀ Keaton is known for his gags and his stunts — including the famous scene from 1928’s “Steamboat Bill Jr.” of an outer wall of a house falling straight onto Keaton, who only escapes injury because he is standing in precisely the right spot where an open window lands.⠀⠀ ⠀⠀ “People like to say he never expressed any emotion on camera, which is clearly not true,” said Patricia Eliot Tobias, who is co-founder and president emerita of the International Buster Keaton Society. “He just did it very, very subtly. In the ‘20s, the acting style on stage — but also in film — was just bigger than life. And that continued on until the ‘50s and ‘60s when you start getting Brando and James Dean and all these people who were underplaying and being as natural as possible — well, that’s what Keaton was doing in the ‘20s.”⠀⠀ ⠀⠀ The Music Box Theatre is running a Buster Keaton retrospective through June 6. Read all about it by clicking the link in our bio. #BusterKeaton #NatalieTalmadge #silentfilm #hollywood #musicbox⠀⠀ ⠀⠀ http://bit.ly/2HMp8HL

0 notes

Photo

One of the giants of silent cinema, Buster Keaton, right, and his wife Natalie Talmadge, pose for a photo as they pass through Chicago on Sept. 27, 1922. ⠀⠀ ⠀⠀ Keaton is known for his gags and his stunts — including the famous scene from 1928’s “Steamboat Bill Jr.” of an outer wall of a house falling straight onto Keaton, who only escapes injury because he is standing in precisely the right spot where an open window lands.⠀⠀ ⠀⠀ “People like to say he never expressed any emotion on camera, which is clearly not true,” said Patricia Eliot Tobias, who is co-founder and president emerita of the International Buster Keaton Society. “He just did it very, very subtly. In the ‘20s, the acting style on stage — but also in film — was just bigger than life. And that continued on until the ‘50s and ‘60s when you start getting Brando and James Dean and all these people who were underplaying and being as natural as possible — well, that’s what Keaton was doing in the ‘20s.”⠀⠀ ⠀⠀ The Music Box Theatre is running a Buster Keaton retrospective through June 6. Read all about it by clicking the link in our bio. #BusterKeaton #NatalieTalmadge #silentfilm #hollywood #musicbox⠀⠀ ⠀⠀ http://bit.ly/2HMp8HL

0 notes