#the matrix trilogy

Text

More of this?

#the matrix resurrections#art#keanureeves#carrie anne moss#neo and trinity#neotrin#the matrix 1999#the matrix trilogy#lana wachowski#ia

135 notes

·

View notes

Text

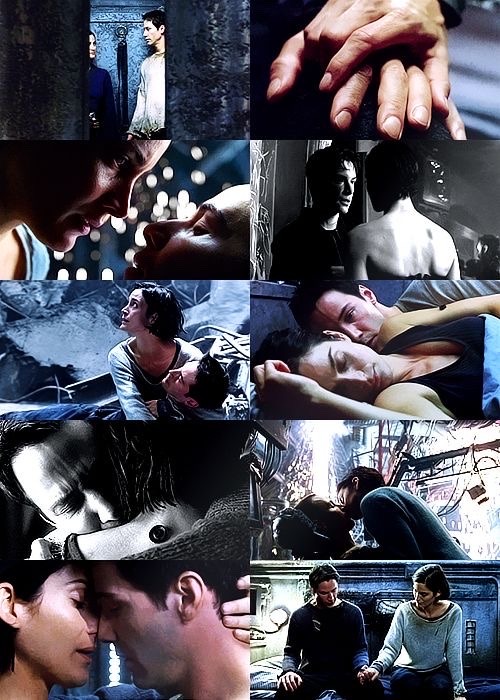

some bnw compilations of my forever loves 🥺

#neo and trinity#neotrin#neo x trinity#the matrix#the matrix trilogy#the matrix resurrections#fanart#i love this style but for some reason im scared to draw just like this and call it done

86 notes

·

View notes

Text

I only just realized now why the Oracle kept offering cookies to Neo. Y’all get the joke? Neo needed the Oracle’s assistance and in return, he “accepted cookies”.

#i see what you did there#the matrix#the matrix 1999#wachowski sisters#keanu reeves#the oracle#neo#thomas anderson#matrix#movie humor#the matrix neo#the matrix trilogy

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

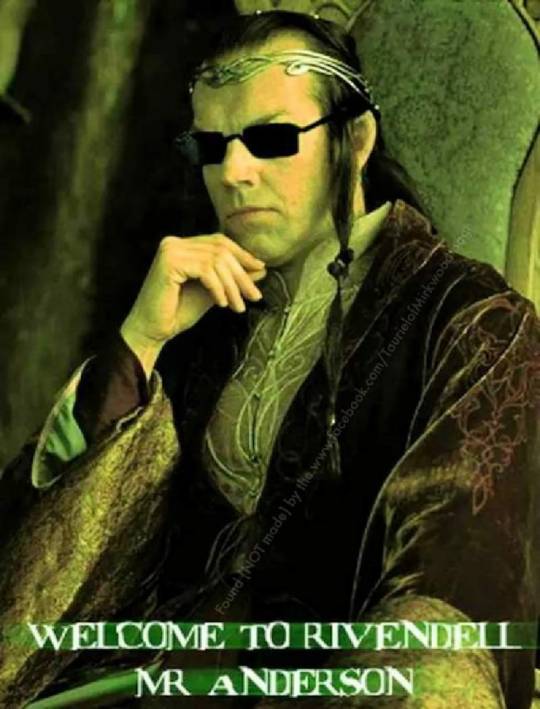

#the matrix trilogy#the matrix revolutions#the matrix#mr anderson#neo#agent smith#lord of the rings#lotr memes#lotr shitpost#lotr#hugo weaving#elrond#rivendell#shitposting#shitpost#dank humor#dankmemes#dank meme#dank memes#dankest memes#dank af#meme#lol memes#memes#fresh memes#funny meme#funny memes#stolen memes#lol wtf#wtf lmao

306 notes

·

View notes

Text

Round 1 Poll 5

Morpheus is the Greek god of sleep and dreams (hence morphine)

Apollo is the Greek and Roman god of music, healing, prophecy, archery etc.

#tournament polls#godsnames tournament#round 1#morpheus the matrix#the matrix trilogy#the matrix#the matrix morpheus#apollo animal crossing#apollo ac#ac apollo#animal crossing#ac#acnh fandom#acnh community#acnh#acnl#acnl community#acnl apollo#acnh apollo

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

bondage and binaries: autonomy recontextualised as a narrative device in science fiction

increasingly popular in mainstream media, science fiction has deep roots in both ancient storytelling and the gothic. the genre covers an expanse of themes that remain socially relevant throughout the entirety of its career; autonomy, transgression, transformation, and corruption. these themes originate from the gothic, the heart of many modern genres. science fiction repurposes gothic themes in fantastical, dystopian and extra-terrestrial contexts and serves as both a well-received source of entertainment and a mode of social commentary. consistent through various eras of sci-fi is the theme of autonomy. much like the gothic, sci-fi stories reflect the social fears prevalent at the time of writing: the fear of a loss of autonomy has always remained an anxiety of western audiences. this fear presents itself in various contexts throughout time. for instance, western societies have dreaded losing autonomy to religious figures abusing their authority (1790s), eastern european immigrants (1890s), and the corruption of the state and technology (1990s). matthew gregory lewis’ ‘the monk’, bram stoker’s ‘dracula’ and the wachowski sisters’ ‘the matrix’ address all these, respective to their time period. bondage has it’s place as a narrative device when it comes to depictions of autonomy as many authors use restraints as a tool to create a sense of helplessness against threat, or to symbolise social or interpersonal constraints. the core difference, of course, between restrains and bondage is that bondage exists in a sexual context and provides gratification for one or both of the parties involved. another key trope of the gothic, and by extension science fiction, is the involvement of taboo, perverse or otherwise transgressive behaviours. the atypical, ‘transgressive’ nature of bdsm gives it’s use in media that relevance, fulfilling two notions of the genre at once. additionally, both styles, at least in their earlier stages, utilise what is referred to as ‘dark romanticism’. this involves taking the stylised language of romantic literature, characterised by purple prose, decadent architecture, etc, and recontextualising it in darker, more morbid settings. the contrast between this lyrical writing and the macabre, violent, alien or taboo content that it is used to describe creates an uneasy, disjointed feeling for audiences. the dynamic between language and content weaves uncanniness into the structure of both genres, which defines them and distinguishes them from other forms of storytelling. for this reason the nature of bondage is integral to the discomfort that sci-fi relies on.

to understand the significance of this writing style and how it characterises science fiction, we need to first understand the chronology of the genre and what impacted its development over time. while sci-fi as we know it today is largely influenced by the gothic, we see fantastical elements in some of the earliest works of fiction, such as the epic of gilgamesh (around 2000 bce) and the indian poem ramayana (5th-4th century bce). ramayana tells of vimana, which are mythological flying palaces or machines that have the ability to travel underwater, into outer space, and to use advanced weaponry to decimate cities. these early references to technology, often used as narrative devices, are a common theme among ancient works of literature. similar examples include the rigveda collection of sanskrit hymns from approximately 1700-1100 bce; the first book contains a depiction of ‘mechanical birds’ that are ‘jumping into space speedily with a craft using fire and water…containing twelve pillars, one wheel, three machines, three hundred pivots and sixty instruments.’ descriptions of technological inventions like this can be found both in early literature, and in later works such as mediaeval stories. it was just prior to the era known as the ‘enlightenment’, which is credited to have begun in 1685, that science fiction started to morph into the form that we see today. 16th century european works such as thomas moore’s ‘utopia’ (1516) and ‘the faust legend’ served as early prototypes of science fiction tropes. moore’s work was the basis for the utopia motif used in sci-fi, similar to how the ‘faust legend’ exemplified the emerging ‘mad scientist’ trope. when the enlightenment era began in europe, it signalled a dramatic shift in thinking, from blind religious faith to knowledge obtained by ‘means of reason and evidence of the senses.’ this was largely influenced by the separation of the church and state, and sparked a wave of speculative fiction concerning the sciences, including: jonathan swift’s ‘gulliver’s travels’ (1726), exploring alien cultures and unusual applications of science, and margaret cavendish’s ‘the description of a new world, called the blazing-world’ (1666), describing a noblewoman’s discovery of an alternate world in the arctic. however, mary shelly’s 1818 ‘frankenstein’ is widely regarded as a major turning point for modern science fiction. shelly’s gothic horror text is the moment where sci-fi and the gothic converge and began to share core elements before developing in their own separate directions again.

shelly’s use of science, and of technology beyond the scope of scientists in her time period as a conceit to drive the narrative is a hallmark of science fiction as we engage with it in the twenty-first century. she develops upon the notion of a ‘crazed scientist’, using the contrast between technology and religion as an extended rhetorical device to alienate frankenstein’s monster. brian aldiss, in ‘billion year spree’ makes the case that ‘frankenstein’ represents ‘the first seminal work to which the label [science fiction] can be logically attached.’ he goes on to argue that science fiction in general derives from the gothic horror novel. the usage of science as a narrative device is one among multiple tropes and elements that shelly imparted to sci-fi with her work. in having an ‘alien’ character fulfil the role of antagonist, shelly comments on the human condition from a new perspective. as put by kelley hurley, ‘through depicting the abhuman, the gothic reaffirms and reconstructs human identity.’ frankenstein’s monster, referred to often as ‘the creature’ is born into bondage; a popularised image from the novel, and several film adaptations, is that of the creature strapped to a board surrounded by rudimentary scientific equipment. from his first introduction to the world, he has no autonomy. these restraints strip him of humanity and reduce him to an experiment. they are not only physical and have practical use, but are symbolic over his general lack of control over the creation of his body, this perverse ‘otherness’ and the public’s decision to outcast him. frankenstein���s monster is an alien in every sense of the word, and it is the subjugation he is born under that characterises him as such. shelly’s work emerged just prior to the fin de siecle (turn of the century), where western science experienced rapid development, which in turn increased the volume of speculative fiction being produced. after ‘frankenstein’, the gothic and science fiction generally parted ways again, but sci-fi now had a host of characterising traits lended to it by shelly’s novel. the general recipe for modern science fiction is a combination of fantasy literature, gothic horror, and advances in western science, allowing us to pinpoint the fin de siecle as a catalyst for the development of the genre. as the era continued, more proto-science fiction was published; most notably was ‘journey to the centre of the earth’ (1864), by jules verne. the tale combines adventure, romance, current technology and predictions of future technology. lyon sprague de camp, an author active in the ‘golden age’ (1940/50s) of science fiction, refers to verne as ‘the world's first full-time science fiction novelist.’

understanding the outlined framework that modern science fiction operates under, we have space to explore the relationship between bondage and sci-fi in detail. in ‘aesthetic violence and women in film’, joseph h kupfer describes violence as having three framings: ‘symbolic, structural and as a narrative essential.’ as previously discussed, violence is an integral factor in the structure of science fiction, starkly contrasting the writing style to create unease. as a narrative device, restraints are often used in conjunction with rising conflict, to create adversity for characters that drives the plot onwards; this is how it functions as a ‘narrative essential.’ the final facet of the relevance of violence is symbolic. typically, women, queer men and ethnic minorities in fiction experience violence on a symbolic level; their identities are seen as purely political, and thus they face adversity against an themselves as an idea rather than as individual people. both the gothic and science fiction rely on the use of the ‘Other’, usually referring to uncanny or supernatural creatures, and often minority characters are ‘Othered’ to code them as a threat to audiences. in this instance, physical restraints are often representative of social, interpersonal or systemic barriers against a character, and by extension, against the minority that they belong to. to exemplify this, we can turn once again to shelly’s ‘frankenstein.’ while frankenstein’s monster is not immediately recognisable as a minority, lennard j davis has insisted the ‘creature’ is disabled or at least treated as such: ‘hideous appearance...inarticulate, some- what mentally slow, and walks with a kind of physical impairment.’ this interpretation of the character leans more towards the social model of disability, rather than defining disability as an impairment of the body or mind, making his argument somewhat controversial. frankenstein’s monster is not functionally hindered, but he is characterised by his disfigurement and unconventional appearance, which davis refers to as ‘a disruption in the visual, auditory, or perceptual field as it relates to the power of the gaze.’ his estrangement from society reinforces his animosity towards people; bound by the physical limitations of his disability, he develops into a ‘monstrosity’ as a result of his ableist environment. this reading sees ableism through the lens of bondage, as a social restraint or barrier that alienates the creature. he is born into physical restraints, strapped to an operating table, and is followed by metaphysical constraints that bar him from social function and acceptance. in his initial creation, what defines our understanding of the use of bondage is the power dynamic; victor is the dominant authority, controlling the movements of the creature, while the creature himself is subordinate to him, with no birthright to autonomy. his inability to control what victor inflicts upon him is illustrated by his restraints, and becomes an extended metaphor for his alienation and lack of autonomy throughout the novel. shelly’s work serves as a commentary, intentional or not, on the estrangement and ‘othering’ of disabled peoples and the impacts this has on their wellbeing and understanding of themselves. additionally, the novel functions almost as a warning tale surrounding the concept of abusing the development of science, and ‘playing god’ as victor does.

adjacent to science fiction is the genre of magical realism. it utilises the fantasy aspects of sci-fi and combines them with a realistic worldview to blur the lines between magic and reality. angela carter’s ‘the erl king’ (1979) is a prime example of using fantasy to illustrate social and systemic bondage in similar ways to sci-fi. carter uses imagery of caged birds to create a visceral picture of female entrapment. interestingly, the metaphor of caged birds can be likened to that of emerging feminism. in mary wollenstonecraft’s ‘a vindication of the rights of women’(1792), she argues that women of the eighteenth century were ‘confined in their cages like the feathered race.’ similarly, carter refers to ‘larks stacked in their pretty cages you’ve lured.’ rather than reinforce the idea that femininity is inherently trapping, carter uses this concept to create an almost tangible illustration of the narrator breaking the cycle of this ingrained imagery. in freeing the erl king’s victims and usupring his position of sexual power, the narrator subverts traditional tropes of female submission and prevents violence against women rather than indulging in it. this is evidence of carter’s signature feminist twist: she writes from the perspective of second-wave feminism. the use of ‘caged bird’ imagery as an allegory for violent and sexist systems is reminiscent of the usage of restraints in science fiction and indicates its relevance across similar genres. sexism and female entrapment are forms of social bondage in ‘the erl king’ the same way ableism is in frankenstein. genre differences aside, carter’s work is an example of how bondage as a narrative device has developed throughout literature. while in more traditional texts, it is used to trap and villainise ‘Othered’ characters, or to demonstrate an antagonist is a threat to audiences autonomy, more modern texts take the approach of reclamation. not only does carter subvert the roles of bondage to allow minorities to shift the power dynamic, she holds up a mirror to society and allows them to witness the abuse of power that she is dismantling. this subverted approach to bondage as a narrative device began to emerge in western literature in the 1970s. second wave feminism and the beginning of what is known as the ‘post civil rights movement’ era in the united states shifted the dynamics of western society in a way that we see reflected in media. as more legislation was put into place in both the united states and united kingdom to protect the rights of more marginalised groups, media produced at the time began to reflect these sentiments. while this does not apply to all movies and literature, many authors began depicting the state as the topic of fear, rather than villainising minorities.

a core example of dystopian fiction that comes to mind is margaret atwood’s ‘the handmaid’s tale’ (1985). themes of subjugation, autonomy and reproductive rights run through the novel. atwood stated that the novel is speculative fiction, rather than science fiction, as she ‘didn't put in anything that we haven't already done, we're not already doing, we're seriously trying to do, coupled with trends that are already in progress... so all of those things are real, and therefore the amount of pure invention is close to nil.’ while this distinction has massive significance in terms of the social commentary atwood is offering, her work still operates, in part, under the writing structure of science fiction. the year of the book’s release, reviewers commented on ‘the distinctively modern sense of [a] nightmare come true, the initial paralyzed powerlessness of the victim unable to act.’ atwood depicts the social bondage enforced upon women by the theonomic, totalitarian state by building an environment full of physical limitations; women are treated as commodities and are stripped of the right to chose clothing, sexual partners, pregnancy, and so on. these are all forced upon them in very particular ways, to the sexual benefit of both men domestically and men in authority. ‘the handmaid’s tale’ combines two core aspects when it comes to control. the fear of religious figures abusing their authority, which has deep roots in both traditional gothic literature and true historical events, and the fear of a surveillance state, often utilised in modern science fiction.

the 2017 television adaptation of ‘the handmaid’s tale’ uses forms of physical bondage as a clear symbol of control: red or leather ‘masks’ are worn by handmaidens as ritualistic punishment for ‘disobedience’ or ‘independent thought’, covering their mouths, and handmaidens are often forced to wear veils. this use of bondage is multi-dimensional; it prevents women from seeing and being seen, from speaking and being heard. it removes the humanity of the individual and solidifies their objectification.

similarly, a well-loved trilogy in modern sci-fi, the wachowski sisters’ ‘the matrix’ (1999) truly leans into socially relevant anxieties surrounding the corruption of the state. the movie itself was ‘born out of anger at capitalism and the corporate structure and forms of oppression’, according to lilly wachowski. the film’s core message is one of reclamation and rebellion against a controlling state; aside from the anti-capitalist rhetoric driving the plot, many of the constraints shown represent social barriers preventing the population from experiencing reality or affirming their own identities. twenty three years from it’s release, ‘the matrix’ is more widely understood now as an allegory for the sisters’ experiences as transgender women in an unaccepting society. there are various uses of bondage and unbalanced power dynamics built into the plot, largely where the ‘agents’ of the state hold authority and dominance whereas the ‘rebels’ and general population are the subordinates being controlled. an example of this is a scene where the protagonist, neo, refuses to cooperate with these agents. in retaliation, they fuse his lips together, removing his ability to speak for himself and creating a terrifying, mangled version of his original face. neo is then pinned down as a ‘tracking bug’, shown to be a robotic centipede, is implanted in his torso. the agents, the dominant force, take his display of autonomy as a threat, and immediately respond with physical restraints in an effort to control it, or at the very least discourage it with scare tactics. this sentiment is echoed in other media, such as the aforementioned masks in ‘the handmaid’s tale.’ forms of gags are often utilised as the ability to speak opinions, call for help, express oneself holds an incredible volume of inherent social value, and having that ability supressed or blocked creates a far more tangible image of the loss of autonomy that resonates strongly with audiences.

a popular image from ‘the matrix’ comes from the infamous ‘red or blue pill’ scene, where neo is exposed to the physical system used to keep the population in a simulated reality while their ‘bioelectric power’ is harvested by machines. gasping for air in a pod filled with liquid not dissimilar to that of the womb, neo is shown to be one of millions of humans being held in pods and kept alive via medical tubes. this is a particularly visceral method of depicting the world’s population as enslaved; humans are stripped of the ability to experience the ‘real world’ and are not even able or permitted to breathe on their own. the way humans are tied into their ‘pods’ that feed their consciousness into the matrix is an example of sci-fi utilising forms of restraint to represent vulnerability and abuse of power. while this is not, by definition, bondage as it does not include sexual arousal it does exemplify why restraints are a vital narrative device. in the context of the wachowski sister’s film, the constrains represent systemic barriers preventing the population from experiencing reality and affirming their own identities. even in instances like this where restraints are used against a protagonist who does not find pleasure in the experience, the perpetrator, such as the agents in the matrix, tend to react with pleasure and almost delight at having someone captive, and the arousal is on their end of the experience as the dominant figure in this interaction. modern sci-fi often has plots rooted in a protagonist or group of protagonists’ journey to dismantle corrupt systems, systems which are reflected as binding or restricting population’s bodies, choices and autonomy. the agents of these systems take pleasure in enacting this restriction as it is a method of maintaining their power and control. consequently, protagonists reclaiming control serves as a natural way for the tables to turn on oppressors and for the narrative to reach its’ hope-filled conclusion.

the aesthetics of bdsm have their place in modern science fiction, but specifically in the matrix. western gothic and alternative fashion appear to be culturally associated with bdsm accessories, namely chokers, harnesses, garters, and so on. kym barrett, the costume designer for the matrix, has stated ‘[the costumes are] reflecting back more obviously to what’s really going on in the world, so maybe subconsciously people are connecting to it.’ the cast sports ensembles comprised of latex, leather, harnesses and accessories; while their clothes must serve a practical purpose and be appropriate attire for action, this also comes across as a co-opting of bondage gear as an act of reclaimation. barrett goes on to explain, ‘when they go into the matrix, they create their persona, which is how they see themselves.’ the depth of these characters centres around their reactions to their oppression, and co-opting symbols of this oppression helps to reinforce their fight against it.

other iconic fashion uses of bondage such as vivienne westwood’s alternative lines of clothing follow a similar vein, described as ‘clothing and imagery that appear dirty, ripped, scarred, shocking, spectacular, cruel, traumatised, sick, or alienating.’ this description matches western societal perspectives on bdsm, specifically the practice of bondage. uses of bondage in the mainstream are often a tool in shock fashion, largely influenced by both the gothic and by punk. punk subculture in particular is built upon shock culture, and utilises bondage alongside the themes of anarchy and anti-capitalism to promote a deeply political message. again, bondage gear and physical restraints are co-opted to form an anti-establishment narrative that jeers in the face of social restraints. despite music and fashion not being the same as literature, we can still see bondage being used as a narrative device. westwood’s sado-masochistic inspired clothing saw the addition of a punk line, named seditionaries, in 1976 after the designer met with the sex pistols. as previously discussed, what defines the gothic genre is the uncanny relationship dynamic between two binaries: romantic language and horror content. this translates to the worlds of both fashion and music, where gothic or alternative content relies on the uneasy contrast between the glamour of fashion or the melodic sound of a song and the shocking, counter-culturalist ‘traumatised’ method of presentation, be it the bdsm influence in the design of a garment or the macabre lyrics. this places bondage at the forefront of alternative media and reinforces its’ relevance as a narrative device.

the history of science fiction narratives is peppered with taboos, bent social conventions and abuses of power. the genre’s framework is inherently a development of gothic framework, recontextualised in a fantasy setting. we rely upon science fiction as a means of coping with capitalism; it is therapeutic to see an unlikely hero burst into the office of a space warlord, a corrupt government, a rogue machine, and blow the fucking place up. in order to experience this catharsis, we have to be able to visualise the constraints that they are dismantling, and to see the perverse nature of them in the first place. bondage traps the core sentiment of a narrative in manacles and allows it to violently break free and confront audiences head-on. it asks the audience, do you feel restrained? do the systems restraining you take pleasure in holding you in place? do you see how unjust it is to be controlled? and as our protagonist triggers an exodus of people ripping off the duct tape, loosening the rope, and unlocking the manacles, our narrative device turns to the audience again and asks, do you see how just it is to be free?

i.k.b

#essay#analytical essay#film analysis#literature analysis#literature essay#books and literature#literature student#film student#copyright ikb#the matrix 1999#the matrix analysis#the matrix trilogy#narrative design#frankenstein#frankenstiensmonster#mary shelley#angela carter#the bloody chamber#the handmaids tale#margaret atwood#vivienne westwood#science fiction#sci fi#scifibooks#scifinovel#gothic#gothic novel#gothic literature#gothic architecture#wachowski sisters

98 notes

·

View notes

Text

They really made a 4th Matrix and gave it the right mixture of nostalgia, amazement, action and urgency to make it amazing!

Little touches like having programs working with them and giving them an interactive physical form and having Smith be a douchebag and the therapists black cat named Deja-Vu, set it appart from other continuation films for me.

I absolutely love it!

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

One of my favourite couples ever!

#the matrix 1999#keanu reeves#carrie anne moss#neo#laurence fishburne#the matrix trilogy#trinity#neotrin#lana wachowski#the matrix

114 notes

·

View notes

Text

IT'S MY BIRTHDAY TODAY and you have to see all the favorite and personally meaningful drawings I've made over the years lol

#jjba#jojo's bizarre adventure#jojo no kimyou na bouken#jotaro kujo#jolyne kujo#the matrix#neo and trinity#neotrin#the matrix trilogy#the matrix resurrections#unikitty#unikitty human AU#good omens#ineffable bureaucracy#boxfly

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wow, I'm back and here is my new Trinity photoshoot!

Ph by Johnybslunk

Follow the white rabbit 👀

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Snagged this from Barnes & Noble

#keanu reeves#legends of hollywood#johnny utah#jack traven#neo#the matrix trilogy#john wick#shane falco

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

A little NeoTrin from yesterday

51 notes

·

View notes

Note

in relation to the sci-fi essay, do you think that any other movies or books show the parallels between the sci-fi and gothic genres in a similar sort of way? and with the matrix being the most widely popular movie to argue the points it does showing support for trans people and opposing capitalism and do you think it lead to the ability for more media to bridge the gap between sci-fi and the gothic, but also to openly criticise social systems without fear of it being less popular due to opposing lots of peoples beliefs at the time, or do you think the matrix was done in a way where it allowed for people to ignore the crucial points for their own comfort and not challenge their beliefs?

hi, thanks for the question!! historically, the biggest (and first / most popular) example of a text that bridges the gap between sci fi and the gothic is mary shelley’s frankenstein. the gothic, and by natural extension sci fi, inherently criticises social systems as a part of the narrative structure of the genre. it takes a societal fear such as the fear of people playing god and pairs it with a supernatural being such as frankenstein’s monster in order to create commentary on society’s fears. frankenstein is the most salient example of the gothic and sci fi morphing together, and is definitely the most well known text that bridges the gap between genres. there are many film and stage iterations of the text that are structured in various styles that take different aspects of the text’s social commentary to focus on. sci fi itself is inherently political.

to answer the second part of the question, many gothic and sci fi texts gain popularity years after initial release, when the meaning of these texts is finally understood and the become cult classics. straying slightly from the gothic and sci fi for a second, chuck palahnuik’s fight club is a prime example of a text / movie that wasn’t well received upon release but later became popular - it is a political text that comments on the radicalisation of young disenfranchised men and the commentary is made explicit but it still remains widely misunderstood due to the male dominated fanbase wanting the piece to validate their violence. like your question poses, audiences often ignore the real meaning for the sake of their own comfort. fight club and the matrix show that a text’s criticism of societal norms can be as explicit as possible, but audiences will misinterpret it if they intend to use the text to validate their own ideals. media already has the ability to openly criticise social systems but the question is whether audiences will be receptive to it. authors and directors and playwrights will always be making some commentary on the topic of their piece of media, because media itself is a vehicle for meaning and no media is made without an inherent meaning or without making a statement on its chosen topic. with every piece of media there will always be a portion of the audience that ignores the crucial points for the sake of their own comfort and reinforcing their own beliefs but that doesn’t take away from the meaning itself.

psychologically we can assess the effectiveness of media in conveying its message. there are two systems of persuasion in social psychology: system 1 and system 2. system 1 is fast acting and functions by reinforcing the beliefs individuals already hold, for instance an advert for a product that is already well liked. system 2 is slower and functions by trying to change the beliefs individuals already hold, for instance greta thunberg’s speech to the un. system 2 is more complex and difficult to execute and media like the matrix attempts to execute system 2, aiming to alter the audience’s generally held belief that governments have our best interests in mind and can be trusted, and also implicitly advocating for trans identities to be respected. the reason the movie has become understood decades after its release is because system 2 persuasion is slow and less effective than system one.

this was a very long answer sorry but i hope this has answered your question!! <3

#film analysis#essay#literary analysis#the matrix 1999#the matrix analysis#the matrix trilogy#asks#essay asks#long post#long asks#anon ask

3 notes

·

View notes