#the nation

Text

Title & subtitle:

[Nov. 21] The Harvard Law Review Refused to Run This Piece About Genocide in Gaza: The piece was nearing publication when the journal decided against publishing it. You can read the article here.

Article text:

On Saturday, the board of the Harvard Law Review voted not to publish “The Ongoing Nakba: Towards a Legal Framework for Palestine,” a piece by Rabea Eghbariah, a human rights attorney completing his doctoral studies at Harvard Law School. The vote followed what an editor at the law reviewdescribed in an e-mail to Eghbariah as “an unprecedented decision” by the leadership of the Harvard Law Review to prevent the piece’s publication.

Eghbariah told The Nation that the piece, which was intended for the HLR Blog, had been solicited by two of the journal’s online editors. It would have been the first piece written by a Palestinian scholar for the law review. The piece went through several rounds of edits, but before it was set to be published, the president stepped in. “The discussion did not involve any substantive or technical aspects of your piece,” online editor Tascha Shahriari-Parsa, wrote Eghbariah in an e-mail shared with The Nation. “Rather, the discussion revolved around concerns about editors who might oppose or be offended by the piece, as well as concerns that the piece might provoke a reaction from members of the public who might in turn harass, dox, or otherwise attempt to intimidate our editors, staff, and HLR leadership.”

On Saturday, following several days of debate and a nearly six-hour meeting, the Harvard Law Review’s full editorial body came together to vote on whether to publish the article. Sixty-three percent voted against publication. In an e-mail to Egbariah, HLR President Apsara Iyer wrote, “While this decision may reflect several factors specific to individual editors, it was not brd on your identity or viewpoint.”

In a statement that was shared with The Nation, a group of 25 HLR editors expressed their concerns about the decision. “At a time when the Law Review was facing a public intimidation and harassment campaign, the journal’s leadership intervened to stop publication,” they wrote. “The body of editors—none of whom are Palestinian—voted to sustain that decision. We are unaware of any other solicited piece that has been revoked by the Law Review in this way. “

When asked for comment, the leadership of the Harvard Law Review referred The Nation to a message posted on the journal’s website. “Like every academic journal, the Harvard Law Review has rigorous editorial processes governing how it solicits, evaluates, and determines when and whether to publish a piece…” the note began. ”Last week, the full body met and deliberated over whether to publish a particular Blog piece that had been solicited by two editors. A substantial majority voted not to proceed with publication.”

Today, The Nation is sharing the piece that the Harvard Law Review refused to run.

enocide is a crime. It is a legal framework. It is unfolding in Gaza. And yet, the inertia of legal academia, especially in the United States, has been chilling. Clearly, it is much easier to dissect the case law rather than navigate the reality of death. It is much easier to consider genocide in the past tense rather than contend with it in the present. Legal scholars tend to sharpen their pens after the smell of death has dissipated and moral clarity is no longer urgent.

Some may claim that the invocation of genocide, especially in Gaza, is fraught. But does one have to wait for a genocide to be successfully completed to name it? This logic contributes to the politics of denial. When it comes to Gaza, there is a sense of moral hypocrisy that undergirds Western epistemological approaches, one which mutes the ability to name the violence inflicted upon Palestinians. But naming injustice is crucial to claiming justice. If the international community takes its crimes seriously, then the discussion about the unfolding genocide in Gaza is not a matter of mere semantics.

The UN Genocide Convention defines the crime of genocide as certain acts “committed with the intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such.” These acts include “killing members of a protected group” or “causing serious bodily or mental harm” or “deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part.”

Numerous statements made by top Israeli politicians affirm their intentions. There is a forming consensus among leading scholars in the field of genocide studies that “these statements could easily be construed as indicating a genocidal intent,” as Omer Bartov, an authority in the field, writes. More importantly, genocide is the material reality of Palestinians in Gaza: an entrapped, displaced, starved, water-deprived population of 2.3 million facing massive bombardments and a carnage in one of the most densely populated areas in the world. Over 11,000 people have already been killed. That is one person out of every 200 people in Gaza. Tens of thousands are injured, and over 45% of homes in Gaza have been destroyed. The United Nations Secretary General said that Gaza is becoming a “graveyard for children,” but a cessation of the carnage—a ceasefire—remains elusive. Israel continues to blatantly violate international law: dropping white phosphorus from the sky, dispersing death in all directions, shedding blood, shelling neighborhoods, striking schools, hospitals, and universities, bombing churches and mosques, wiping out families, and ethnically cleansing an entire region in both callous and systemic manner. What do you call this?

The Center for Constitutional Rights issued a thorough, 44-page, factual and legal analysis, asserting that “there is a plausible and credible case that Israel is committing genocide against the Palestinian population in Gaza.” Raz Segal, a historian of the Holocaust and genocide studies, calls the situation in Gaza “a textbook case of Genocide unfolding in front of our eyes.” The inaugural chief prosecutor of the International Criminal Court, Luis Moreno Ocampo, notes that “Just the blockade of Gaza—just that—could be genocide under Article 2(c) of the Genocide Convention, meaning they are creating conditions to destroy a group.” A group of over 800 academics and practitioners, including leading scholars in the fields of international law and genocide studies, warn of “a serious risk of genocide being committed in the Gaza Strip.” A group of seven UN Special Rapporteurs has alerted to the “risk of genocide against the Palestinian people” and reiterated that they “remain convinced that the Palestinian people are at grave risk of genocide.” Thirty-six UN experts now call the situation in Gaza “a genocide in the making.” How many other authorities should I cite? How many hyperlinks are enough?

And yet, leading law schools and legal scholars in the United States still fashion their silence as impartiality and their denial as nuance. Is genocide really the crime of all crimes if it is committed by Western allies against non-Western people?

This is the most important question that Palestine continues to pose to the international legal order. Palestine brings to legal analysis an unmasking force: It unveils and reminds us of the ongoing colonial condition that underpins Western legal institutions. In Palestine, there are two categories: mournable civilians and savage human-animals. Palestine helps us rediscover that these categories remain racialized along colonial lines in the 21st century: the first is reserved for Israelis, the latter for Palestinians. As Isaac Herzog, Israel’s supposed liberal President, asserts: “It’s an entire nation out there that is responsible. This rhetoric about civilians not aware, not involved, it’s absolutely not true.”

Palestinians simply cannot be innocent. They are innately guilty; potential “terrorists” to be “neutralized” or, at best, “human shields” obliterated as “collateral damage”. There is no number of Palestinian bodies that can move Western governments and institutions to “unequivocally condemn” Israel, let alone act in the present tense. When contrasted with Jewish-Israeli life—the ultimate victims of European genocidal ideologies—Palestinians stand no chance at humanization. Palestinians are rendered the contemporary “savages” of the international legal order, and Palestine becomes the frontier where the West redraws its discourse of civility and strips its domination in the most material way. Palestine is where genocide can be performed as a fight of “the civilized world” against the “enemies of civilization itself.” Indeed, a fight between the “children of light” versus the “children of darkness.”

The genocidal war waged against the people of Gaza since Hamas’s excruciating October 7th attacks against Israelis—attacks which amount to war crimes—has been the deadliest manifestation of Israeli colonial policies against Palestinians in decades. Some have long ago analyzed Israeli policies in Palestine through the lens of genocide. While the term genocide may have its own limitations to describe the Palestinian past, the Palestinian present was clearly preceded by a “politicide”: the extermination of the Palestinian body politic in Palestine, namely, the systematic eradication of the Palestinian ability to maintain an organized political community as a group.

This process of erasure has spanned over a hundred years through a combination of massacres, ethnic cleansing, dispossession, and the fragmentation of the remaining Palestinians into distinctive legal tiers with diverging material interests. Despite the partial success of this politicide—and the continued prevention of a political body that represents all Palestinians—the Palestinian political identity has endured. Across the besieged Gaza Strip, the occupied West Bank, Jerusalem, Israel’s 1948 territories, refugee camps, and diasporic communities, Palestinian nationalism lives.

What do we call this condition? How do we name this collective existence under a system of forced fragmentation and cruel domination? The human rights community has largely adopted a combination of occupation and apartheid to understand the situation in Palestine. Apartheid is a crime. It is a legal framework. It is committed in Palestine. And even though there is a consensus among the human rights community that Israel is perpetrating apartheid, the refusal of Western governments to come to terms with this material reality of Palestinians is revealing.

Once again, Palestine brings a special uncovering force to the discourse. It reveals how otherwise credible institutions, such as Amnesty International or Human Rights Watch, are no longer to be trusted. It shows how facts become disputable in a Trumpist fashion by liberals such as President Biden. Palestine allows us to see the line that bifurcates the binaries (e.g. trusted/untrusted) as much as it underscores the collapse of dichotomies (e.g. democrat/republican or fact/claim). It is in this liminal space that Palestine exists and continues to defy the distinction itself. It is the exception that reveals the rule and the subtext that is, in fact, the text: Palestine is the most vivid manifestation of the colonial condition upheld in the 21st century.

hat do you call this ongoing colonial condition? Just as the Holocaust introduced the term “Genocide” into the global and legal consciousness, the South African experience brought “Apartheid” into the global and legal lexicon. It is due to the work and sacrifice of far too many lives that genocide and apartheid have globalized, transcending these historical calamities. These terms became legal frameworks, crimes enshrined in international law, with the hope that their recognition will prevent their repetition. But in the process of abstraction, globalization, and readaptation, something was lost. Is it the affinity between the particular experience and the universalized abstraction of the crime that makes Palestine resistant to existing definitions?

Scholars have increasingly turned to settler-colonialism as the lens through which we assess Palestine. Settler-colonialism is a structure of erasure where the settler displaces and replaces the native. And while settler-colonialism, genocide, and apartheid are clearly not mutually exclusive, their ability to capture the material reality of Palestinians remains elusive. South Africa is a particular case of settler-colonialism. So are Israel, the United States, Australia, Canada, Algeria, and more. The framework of settler colonialism is both useful and insufficient. It does not provide meaningful ways to understand the nuance between these different historical processes and does not necessitate a particular outcome. Some settler colonial cases have been incredibly normalized at the expense of a completed genocide. Others have led to radically different end solutions. Palestine both fulfills and defies the settler-colonial condition.

We must consider Palestine through the iterations of Palestinians. If the Holocaust is the paradigmatic case for the crime of genocide and South Africa for that of apartheid, then the crime against the Palestinian people must be called the Nakba.

The term Nakba, meaning “Catastrophe,” is often used to refer to the making of the State of Israel in Palestine, a process that entailed the ethnic cleansing of over 750,000 Palestinians from their homes and destroying 531 Palestinian villages between 1947 to 1949. But the Nakba has never ceased; it is a structure not an event. Put shortly, the Nakba is ongoing.

In its most abstract form, the Nakba is a structure that serves to erase the group dynamic: the attempt to incapacitate the Palestinians from exercising their political will as a group. It is the continuous collusion of states and systems to exclude the Palestinians from materializing their right to self-determination. In its most material form, the Nakba is each Palestinian killed or injured, each Palestinian imprisoned or otherwise subjugated, and each Palestinian dispossessed or exiled.

The Nakba is both the material reality and the epistemic framework to understand the crimes committed against the Palestinian people. And these crimes—encapsulated in the framework of Nakba—are the result of the political ideology of Zionism, an ideology that originated in late nineteenth century Europe in response to the notions of nationalism, colonialism, and antisemitism.

As Edward Said reminds us, Zionism must be assessed from the standpoint of its victims, not its beneficiaries. Zionism can be simultaneously understood as a national movement for some Jews and a colonial project for Palestinians. The making of Israel in Palestine took the form of consolidating Jewish national life at the expense of shattering a Palestinian one. For those displaced, misplaced, bombed, and dispossessed, Zionism is never a story of Jewish emancipation; it is a story of Palestinian subjugation.

What is distinctive about the Nakba is that it has extended through the turn of the 21st century and evolved into a sophisticated system of domination that has fragmented and reorganized Palestinians into different legal categories, with each category subject to a distinctive type of violence. Fragmentation thus became the legal technology underlying the ongoing Nakba. The Nakba has encompassed both apartheid and genocidal violence in a way that makes it fulfill these legal definitions at various points in time while still evading their particular historical frames.

Palestinians have named and theorized the Nakba even in the face of persecution, erasure, and denial. This work has to continue in the legal domain. Gaza has reminded us that the Nakba is now. There are recurringthreats by Israeli politicians and other public figures to commit the crime of the Nakba, again. If Israeli politicians are admitting the Nakba in order to perpetuate it, the time has come for the world to also reckon with the Palestinian experience. The Nakba must globalize for it to end.

We must imagine that one day there will be a recognized crime of committing a Nakba, and a disapprobation of Zionism as an ideology brd on racial elimination. The road to get there remains long and challenging, but we do not have the privilege to relinquish any legal tools available to name the crimes against the Palestinian people in the present and attempt to stop them. The denial of the genocide in Gaza is rooted in the denial of the Nakba. And both must end, now.

#palestine#uspol#the nation#geopol#long post#the article is paywalled so here it is for ease of access#📁.zip

488 notes

·

View notes

Text

hearts roy, roman's daughter, cousin of tom and shiv's son hibs, a tiny woman with adult braces, overplucked eyebrows, masochistic body piercings, her single father's veins, her lonely father's eyes, her rootless father's mouth - pictured IF she had survived past her infancy, which in this hypothetical universe she did not.

hearts, from shiv's perspective, in the "canon universe" of this fic with the mencken presidency having further destroyed america, in which hearts does not live:

#art#succession#fanart#succession oc#roman roy#shiv roy#hearts#hibernian#logan roy#fanfic#succession fanfic#it was always the plan for there to be hibs and hearts#hibs just has to live with the fact that hearts is dead#GRAAAHHHH. HEARTS#i love her as much as i love hibs so its fun to venture into the even more hypothetical territory where shes still around#why adult braces? pain of course. and aesthetics#shes an odd bird shes a clubber she pretends shes not rich she wears $1700 dollar canada goose jackets#and a lead with a diamond embedded in her neck#the nation

532 notes

·

View notes

Text

Edward W. Said, The Essential Terrorist, in Blaming the Victims. Spurious Scholarship and the Palestinian Question, Edited by Edward W. Said and Christopher Hitchens, Verso, London and New York, NY, 1988, pp. 149-158 (text here)

#graphic design#history#historiography#book#edward w. said#edward said#christopher hitchens#verso#the nation#1980s#2000s

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

by JEROME M. MARCUS

Riotous marchers on college campuses are demanding the creation of a country called “Palestine” on all the territory of the U.N.-recognized State of Israel, entirely free of Jews. The presidents of three prestigious universities can’t say whether calling for the genocide of Jews violates their codes of conduct. Harvard Chabad is told it can’t leave its Chanukah menorah up for eight days because the university doesn’t want to be embarrassed by a photo of a vandalized menorah in Harvard Yard. Jewish students are barricaded behind locked doors or offered an attic to hide in due to threats from racist fellow students.

Given all this, it is not surprising that The New York Times is deeply concerned about the alleged suppression of pro-Palestinian speech on American campuses.

The Times offers the example of The Harvard Law Review’s rejection of a blog post written by Rabea Eghbariah—now completing a doctorate at Harvard Law School—that accuses Israel of committing genocide in Gaza. The Times heavily implies the antisemitic libel that the post offended too many powerful Jewish and Israeli interests. It’s Rep. Ilhan Omar’s “Benjamins” again.

The left-wing magazine The Nation printed the “suppressed” post, revealing that the piece was a shoddy, poorly argued rant containing no supporting evidence and bereft of the serious legal analysis that any law review article requires.

As lawyers know, all legal arguments must be composed of two parts: the facts and the law. Eghbariah’s rant contains neither.

First, the post nowhere acknowledges that Gaza is in a state of war with Israel, declared by Hamas with the explicitly stated goal of eliminating the Jewish state. Now, one could argue that Israel’s military operation, though justified, is disproportionate. But Eghbariah makes no such argument. Indeed, he does not even attempt to assess or disprove any conceivable justification for any military action by Israel in Gaza.

International law is clear that, in order to prove genocide, evidence of the defendant’s “intent to destroy, in whole or in part, the national, ethnical, religious or linguistic group to which victims of the alleged wrongful acts belonged” is necessary.

In one of only two citations of any legal authority in the entire post—a glaring dearth of sources for a piece supposed to be published in a law review—Eghbariah cites this standard. He then claims, “Numerous statements made by top Israeli politicians affirm their intentions.” This sentence contains two links. That is the total extent of Eghbariah’s evidence.

21 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“ Reservation Dogs repeatedly underscores the ordinariness of its characters as a way to challenge the othering gaze. Elders in the community like Brownie (Gary Farmer) or Bucky (Wes Studi) are portrayed as flawed men with their own histories of selfishness instead of as wise old-timers. Similarly, traditional healers like Old Man Fixico (Richard Ray Whitman) and Daniel’s mother Hokti (Lily Gladstone), who’s serving time in prison for undisclosed reasons, are neither especially righteous nor mystical. Instead, these spiritual leaders are merely everyday people dedicated to helping their community. “

Vikram Murthi, “How Reservation Dogs Changed the TV Landscape,” The Nation, November 21, 2023.

(via How “Reservation Dogs” Changed the TV Landscape | The Nation)

22 notes

·

View notes

Photo

(via Black History, All Year | The Nation)

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

“We’ve got to break the back of this generation of Democratic leaders,” Kissinger told Nixon, plotting to use foreign policy for domestic advantage. Nixon agreed: "We’ve got to destroy the confidence of the people in the American establishment.”

[Joan Walsh :: The Nation]

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Spread love, it’s the Brooklyn way.”

House Democratic leader Hakeem Jeffries clearly won the day on Tuesday. He made history as the first Black House caucus leader; it was also the first time (to the best of my fact-checking ability) Brooklyn’s Biggie Smalls was quoted on the House floor. While Republicans savaged one another, Democrats spread love. Jubilant, they looked like they were in the majority, not (narrowly) outnumbered by Republicans. While it’s still extremely unlikely, Jeffries went to bed closer to being House Speaker than he was Tuesday morning. Let it be said that in all three roll calls, Jeffries got 212 votes, at least nine more than McCarthy, and only a few shy of what the next Speaker will need.

Debased House GOP leader Kevin McCarthy is still not speaker, after three roll call votes in which he actually lost support. What happens when a man tries to sell his soul but finds no buyer? (A question for House Conference Chair Elise Stefanik, too.) McCarthy gave the wing nuts virtually everything they asked for—the ability for only five members to force a vote to oust him as leader, key committee appointments, other rules changes, a gutted ethics committee, the ability to defund federal departments they don’t like. But they didn’t budge, and in fact their numbers climbed from an estimated five in the morning to 20 at 5 PM.

That’s when Representative Tom Cole moved to adjourn until noon on Wednesday. There had been talk that McCarthy and Co. wanted at least one more roll call vote, to “wear down” the opposition. But since the opposite was happening—the opposition was emboldened—most of the House did McCarthy a solid by voting to end his grueling day of trial by procedural combat.

Let it not be said, however, that the divided House GOP majority changed nothing. Shortly after noon on Tuesday, House security officials took down the weapon-detecting magnetometers, installed after January 6, that were intended to make sure no one entered the House chamber with a weapon. So there’s that.

There will be plenty of assessments of McCarthy’s plight after Tuesday, but I want to focus on Jeffries’s victory, even if it only lasts a day. It was also Nancy Pelosi’s: As she turned over her leadership post to Jeffries, she also bequeathed him a caucus schooled in sticking together, left, liberal, and center, when it matters most. I don’t think Beltway reporters addicted to a “Dems in disarray” story line ever understood what Pelosi accomplished, whether it was delivering her whole caucus for the Affordable Care Act in 2010, when the left was itching to bolt, to all the times she kept her members united under Donald Trump, to the selective defections she allowed—by the so-called Squad as well as centrists—as she pushed President Biden’s agenda in the past two years, knowing that certain members might need to go their own way given the proclivities of their districts.

So far, Jeffries hasn’t needed to grant any dispensation to Democrats to vote for someone else as Speaker. He won all Democratic votes, in a Speaker battle, for the first time since Pelosi did in 2007. That makes sense: Even though he is a liberal not unanimously beloved on the left, he won his caucus leader post by unanimous acclamation. Any reservations members had about him, whether from the left or the center, got subsumed by learned behavior: Being united has paid dividends for Democrats. Why stop now?

Midafternoon Tuesday, several reporters with GOP sources began floating the idea that Democrats might leave the floor, reducing the overall number of votes McCarthy would need to become Speaker. (The victor needs a majority of those present and voting for a named candidate, not of the entire House). I called bullshit at the time. It made no sense, given how Republicans were self-immolating. If there were a vital House Democratic center, maybe there would be people trying to cut deals with Republicans. (And while there isn’t, it’s still possible some incompetents are trying.)

Actually, a vital House Democratic center might be approaching Republicans in districts Joe Biden won to get them to vote for Jeffries. There are at least five: in Southern California, central New York, and southeastern Pennsylvania. Maybe Problem Solver Josh Gottheimer can work his magic? I doubt it. In fact, a much-gossipped-about photo capturing Representative Alexandria Ocasio Cortez chatting amiably with GOP psycho dentist Paul Gosar, who once produced a cartoon of himself killing the Bronx-Queens leader, turned out to show AOC gently disabusing Gosar of the notion that Democrats were ready to walk out and make it easier for McCarthy to win. “Dems in disarray,” d’oh! That message is strong.

It must be said that despite ideological fractures within the Democratic caucus, Jeffries had the unanimous support of the Congressional Black Caucus, and his historic leadership role, by most accounts, trumped policy differences. Progressives bristled last cycle when he joined with Gottheimer to thwart progressive Democratic challengers and refused “to bend the knee to democratic socialism,” as he put it. (As if anyone asked him to.) But when I heard Cori Bush cast her vote for Jeffries the first time, I knew he’d get all 212 Democrats. And he did. Three times.

After a brutal House GOP caucus meeting Tuesday morning, implacable McCarthy foe Matt Gaetz of Florida, who seems to have survived sex trafficking accusations, allegedly said, “I don’t care if we…elect Hakeem Jeffries.” I don’t believe that any more than I believe anything Gaetz says, but it’s still out there. Not counting on it, not betting on it, but whatever happens, Jeffries is in a hugely stronger position after this GOP multiple-vote shit show than he was even when Tuesday began. No matter who becomes Speaker, he’s going to be the most important House leader.

#us politics#news#2023#the nation#op eds#118th congress#joan walsh#speaker of the house#rep. Hakeem Jeffries#rep. kevin mccarthy#rep. elise stefanik#rep. Tom Cole#rep. nancy pelosi#rep. alexandria ocasio cortez#rep. paul gosar#Congressional Black Caucus#Democrats#rep. matt gaetz#republicans#conservatives#progressives

50 notes

·

View notes

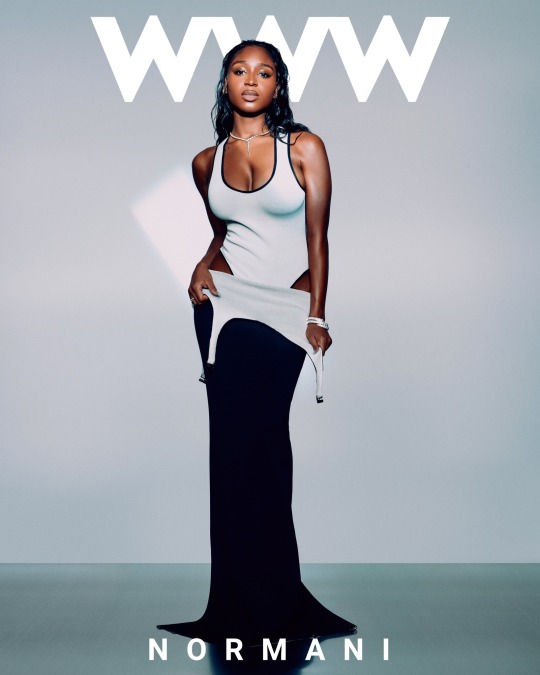

Text

Normani for Who What Wear Magazine 🚀✨

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

[alt text: But the state of Israel was not created for the salvation of the Jews; it was created for the salvation of the Western interests. This is what is becoming clear (I must say that it was always clear to me).

The Palestinians have been paying for the British colonial policy of "divide and rule" and for Europe's guilty Christian conscience for more than thirty years.

- James Baldwin

The Nation, 1979

graphic and photo provided by the James Baldwin Archive in instagram

#the united states doesn’t give a fuck about jewish people#the idea that zionism is a moral position is a weak farce#free palestine#james baldwin#palestine#the nation

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

(Dec. 29) [Article] by Afnan Abu Yahia & Lila Hassan

Title & subtitle:

The Impossibility of Reporting the Story of Gaza: The work of Gaza’s journalists has been essential these past months, but as the challenges of reporting continue to mount, the world is getting only a fraction of the story.

Article text:

Samer Abu Daqqa loved being a journalist. A cameraman for over 20 years with Al Jazeera, Abu Daqqa, 45, had covered at least seven wars. Israel’s war on Gaza, however, would turn out to be his last.

While covering an air strike at a United Nations–run school on December 15, Israeli forces shot Abu Daqqa. Intense shelling prevented an ambulance from reaching him—three paramedics were killed trying to get to the area—and he was left to bleed for over five hours, succumbing to his injuries just as the Palestinian Health Ministry got approval from the Israeli military to retrieve him. In the end, they brought his body to the hospital, where his family said goodbye. Medical workers removed his bloodied press vest and helmet, which were placed over his body at his funeral.

Since the beginning of Israel’s war on Gaza, which has now killed more than 20,000 Palestinians, journalists have been on the front lines, both as witnesses and victims. For more than two months, as Israel has rained bombs on Gaza, they have rushed from refugee camps to hospitals, and from hospitals to schools and back, trying to stay safe while covering what they describe as their own genocide. According to the Committee to Protect Journalists, 68 journalists have been killed in Gaza, Israel, and Lebanon since October 7, making this the deadliest conflict since the CPJ began tallying press fatalities. The International Federation of Journalists estimates that at least 66 journalists have been killed in Gaza alone. Many have also lost their families. On October 26, Ahmed Abu Artema, a contributor to The Nation as well as a poet and activist, was seriously injured and lost his young son when Israel bombed his father’s house.

“What is happening now is unprecedented,” said Sherif Mansour, the Middle East and North Africa program coordinator at the CPJ. In 2022, the CPJ reported that a total of 68 journalists and media workers were killed worldwide; Gaza reached that number in just over two months.

Journalists, said Mansour, “are the ones on the front lines and they are the ones we need the most, but they are also the most vulnerable.”

It’s hard to overestimate the importance of the Palestinian journalists in Gaza right now. They, after all, are the only ones who have been reporting from the Strip since Israel instituted a total siege on October 9 and banned foreign press from entering. Their work has been essential and their commitment unceasing; yet, as the weeks have passed, the mounting challenges of reporting have meant that the world outside of Gaza is getting only a fraction of the story. Even social media has offered only a partial solution, as many of the platforms regularly censor Palestinian voices.

By far, the biggest challenge for journalists is simply staying alive. The struggle to survive while reporting is an all-consuming endeavor. But this struggle has been seriously compounded both by the conditions of war and the shattering effects of Israel’s total siege of the Strip. Food and water are scarce; fuel is dwindling, electricity inconsistent, and cell phone service undependable; many journalists no longer even have homes to return to.

For journalists, this has meant everything from reporting on empty stomachs to writing up stories while worrying about when and how they will find water. One journalist has used Gaza’s salty seawater to bathe, and another said he shared half a liter of clean water for four days with colleagues. Meanwhile, it has become normal to wait for food in hours-long lines and still not manage to buy anything, said Nazar Sadawi, a correspondent with Turkish Radio and Television. “I don’t have the luxury of time. I don’t have 10 hours to wait for my turn,” he said, explaining that instead he lives mostly off of bread, tea, and biscuits. “Aid trucks bring in canned beans, water, and some medicine, but it doesn’t even meet 5 percent of the need. We can literally reach a famine.”

Sadawi left the north for the south after Israel issued an evacuation warning on October 11 to the entirety of north Gaza’s 1.1 million people. “You can call me homeless” or a “displaced person,” he said. The neighborhood around his home has since been bombed, and his parents’ house as well as his car have been destroyed in Israeli air strikes. With whole buildings either completely or partially destroyed, finding anywhere with a bed or couch is near impossible. Sadawi is lucky to get two to three hours of sleep, he said, usually on a hospital chair on the sidewalk, and without a blanket. “I don’t have clothes. I left those at home,” he said. The hospital is also where he showers and uses the restroom, which also requires waiting in hours-long lines.

Meanwhile, Sadawi said, the frequent shutdowns of Internet and cellular service have meant that reporting has reverted to old-school methods—trekking from area to area over debris and destroyed roads, surveying survivors and witnesses for casualty numbers, and listening to the radio for context and conditions. “The news that I used to get in three minutes I now get in an hour or two,” he said.

Before Gaza lost consistent access to the Internet and cellular service, journalists used to call each other to swap information. But now, “I call the people who are covering air strikes 20 times for the line just to connect, and just so I can check on if they’re still alive,” he said. Satellite phones could solve this, but Sadawi said it’s impossible to obtain one now given the blockade. “Only five journalists probably have them, and they got them before the war,” he said. Often, Sadawi has to pick between calling his family or the woman he loves. “She lives somewhere I can’t reach.”

Journalists no longer keep regular working hours. Because Israel has stopped “roof knocking”—alerting people when an air strike is incoming—journalists cover the aftermath at all times of the day, but they are eager to be sheltered by sunset (around 5 pm), because shelling is strongest in pitch-black conditions. And because the bombardment is constant, the noise, as well as nightmares make it hard to sleep—something both interviews and a survey of journalists’ social media posts show.

This, along with the trauma of lost loved ones, lost homes, constant fear, and the relentless sight of death, is wreaking havoc on journalists’ future mental health, said Ghazi Aloul, a Roya News correspondent. Aloul, who has spent only six hours at home since November, is living in the same areas he is covering, relying on hospitals for rest and charging his equipment. “I have experienced many painful moments in this war,” Aloul said. “Previous wars were not this brutal.”

Within this landscape of brutality, “the most sensitive scenes for me to see are children bleeding and injured, because immediately I think of my little 2-and-a-half-year-old girl,” he said. Still, he keeps working. “I try to stay firm and convey my work, photographs, and the truth, because my daughter could be among the dead, and I would need someone to convey her voice and image,” he added.

Aloul says that he himself is not afraid to die. ”If that’s my destiny, then so be it,” he said. But he cannot bear the idea of losing his loved ones. “Experiencing loss is extremely painful and unbearable, and that’s what I can’t get out of my head.”

As the stories of murdered journalists have mounted, many in Gaza have come to suspect that Israel is deliberately targeting the press. This fear became particularly acute after an Israeli air strike hit and killed the place where the family of Aljazeera’s Gaza bureau chief, Wael Aldahdouh, was sheltering. “They are taking revenge on us through our children,” he said, sitting next to his dead son’s body. On December 15, Aldahdouh was shot in the arm while reporting on an air strike on Haifa School in Khan Younis; it was during the same reporting trip that Abu Duqqa was shot and killed.

Israel’s military has repeatedly denied that it targets journalists. “The IDF takes all operationally feasible measures to protect both civilians and journalists. The IDF has never, and will never, deliberately target journalists,” a spokesperson told The Nation. “Given the ongoing exchanges of fire, remaining in an active combat zone has inherent risks. The IDF will continue to counter threats while persisting to mitigate harm to civilians.”

Yet the IDF’s actions have continued to raise questions for journalists, as have statements from the Israeli press. Hours after the strike that killed Aldahdou’s family, Avi Yehekli, of Israel’s Channel 13, said, “Generally, we know the target. Like today, there was a target on the family of an Aljazeera journalist.”

Meanwhile, as fear of being targeted by an Israeli air strike has grown, The Nation found that several journalists have pleaded with others in their profession not to add a location to their social-media posts. Aseel Moussa, a correspondent in Gaza with Middle East Eye, believes that Israel will continue to kill journalists because it has never been held accountable in the past. (From 2000 to 2022, Israel killed 55 Palestinian journalists, according to the Palestinian News Agency. Last year, Israel admitted, after several months of denials, that it was responsible for shooting and killing Palestinian-American Shireen Abu Akleh.)

“There is nowhere safe in Gaza for anyone of any profession,” said Moussa, who evacuated eastern Gaza for the south last month only to be met with more bombing. Two days before our interview, Moussa said, her relatives’ home was hit, killing nine family members. Seven were children.

Compounding all of these horrors is the painful reality that, even when journalists do manage to report, their stories can have limited reach. For years, digital rights groups and tech watchdogs have claimed that Meta censors content related to Palestine and that it also monitors Arabic content more excessively than it does Hebrew content. Last week, Human Rights Watch found that Meta systematically censors Palestinian content around the world.

This kind of shadow banning, as it is called, stymies the world’s access to content coming out of Gaza. Motaz Azaiza, a photojournalist who has gained a global following of over 17 million followers on Instagram and was named GQ Middle East’s Man of the Year, shared screenshots from Meta indicating that he’d violated Instagram’s community guidelines for posting images; he also shared notifications alerting him that some of his content had been taken down. Meta has not responded to multiple requests for comment.

Still, despite the mounting threats and dangers, what matters to Middle East Eye’s Moussa most is his work. “When I can’t publish my articles or cover the stories around me, that’s when my feelings of helplessness deepen,” he said.

And so, journalists keep reporting, knowing that it might lead to their death. In the last month, several journalists have written their own anticipated obituaries online, sharing their last words, and predicting their own deaths. Roshdi Sarraj, an admired journalist whom Moussa described as “at the top of the field,” was one of them. In one of his last personal posts, Sarraj wrote on Facebook: “We will not leave. And when we do leave Gaza, we will go to the sky, and the sky only.” He was killed days later in an air strike, survived by his wife and baby girl, who turned 1 on November 6.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

the thinkers

#i swearjhghghg to god i will finish this art soon#i just have so many more to color#[is ground into a paste]#[is ground into a paste][is ground into#shiv roy#siobhan roy#tomshiv baby#hibernian#succession#the nation#art#he thinks hes the thinker#thank you all for your tolerance

158 notes

·

View notes

Text

Edward in Palestine. Reflections on Edward Said 20 years after his death, by Raja Shehadeh and Penny Johnson, «The Nation», September 27, 2023 [Photo: Sophie Bassouls/Getty]

#photography#magazine#edward w. said#edward said#raja shehadeh#penny johnson#sophie bassouls#the nation#2020s

43 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Don Cornelius’s faith that Black culture would attract a mass audience—and his devout belief that Black culture should be in the hands of Black people—make the program he created a radical touchstone 50 years after its debut

(via Soul Train and the Desire for Black Power | The Nation)

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Diary entries from Atef Abu Saif in Gaza pt. 2

7 notes

·

View notes