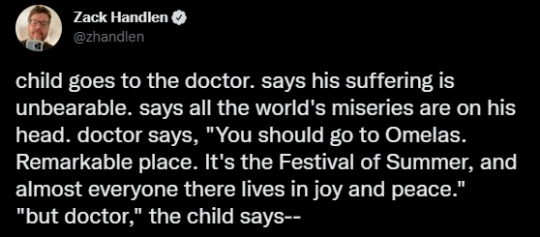

#the ones who walk away from omelas

Text

"The idea of reforming Omelas is a pleasant idea, to be sure, but it is one that Le Guin herself specifically tells us is not an option. No reform of Omelas is possible — at least, not without destroying Omelas itself:

If the child were brought up into the sunlight out of that vile place, if it were cleaned and fed and comforted, that would be a good thing, indeed; but if it were done, in that day and hour all the prosperity and beauty and delight of Omelas would wither and be destroyed. Those are the terms.

'Those are the terms', indeed. Le Guin’s original story is careful to cast the underlying evil of Omelas as un-addressable — not, as some have suggested, to 'cheat' or create a false dilemma, but as an intentionally insurmountable challenge to the reader. The premise of Omelas feels unfair because it is meant to be unfair. Instead of racing to find a clever solution ('Free the child! Replace it with a robot! Have everyone suffer a little bit instead of one person all at once!'), the reader is forced to consider how they might cope with moral injustice that is so foundational to their very way of life that it cannot be undone. Confronted with the choice to give up your entire way of life or allow someone else to suffer, what do you do? Do you stay and enjoy the fruits of their pain? Or do you reject this devil’s compromise at your own expense, even knowing that it may not even help? And through implication, we are then forced to consider whether we are — at this very moment! — already in exactly this situation. At what cost does our happiness come? And, even more significantly, at whose expense? And what, in fact, can be done? Can anything?

This is the essential and agonizing question that Le Guin poses, and we avoid it at our peril. It’s easy, but thoroughly besides the point, to say — as the narrator of 'The Ones Who Don’t Walk Away' does — that you would simply keep the nice things about Omelas, and work to address the bad. You might as well say that you would solve the trolley problem by putting rockets on the trolley and having it jump over the people tied to the tracks. Le Guin’s challenge is one that can only be resolved by introspection, because the challenge is one levied against the discomforting awareness of our own complicity; to 'reject the premise' is to reject this (all too real) discomfort in favor of empty wish fulfillment. A happy fairytale about the nobility of our imagined efforts against a hypothetical evil profits no one but ourselves (and I would argue that in the long run it robs us as well).

But in addition to being morally evasive, treating Omelas as a puzzle to be solved (or as a piece of straightforward didactic moralism) also flattens the depth of the original story. We are not really meant to understand Le Guin’s 'walking away' as a literal abandonment of a problem, nor as a self-satisfied 'Sounds bad, but I’m outta here', the way Vivier’s response piece or others of its ilk do; rather, it is framed as a rejection of complacency. This is why those who leave are shown not as triumphant heroes, but as harried and desperate fools; hopeless, troubled souls setting forth on a journey that may well be doomed from the start — because isn’t that the fate of most people who set out to fight the injustices they see, and that they cannot help but see once they have been made aware of it? The story is a metaphor, not a math problem, and 'walking away' might just as easily encompass any form of sincere and fully committed struggle against injustice: a lonely, often thankless journey, yet one which is no less essential for its difficulty."

- Kurt Schiller, from "Omelas, Je T'aime." Blood Knife, 8 July 2022.

#kurt schiller#ursula k. le guin#quote#quotations#the ones who walk away from omelas#trolley problem#activism#introspection#discomfort#reform#revolution#suffering#ethics#morality

10K notes

·

View notes

Text

(source)

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

The Ones Who Found The City

Ursula K. LeGuin's "The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas" is a classic short story, and obviously I knew of it, but I'd never actually read it until recently. Well, I finally got around to it, and as many timeless classics do, it got stuck in my brain. This story is my - response? homage? sequel? pale imitation? - to it. I suggest you go and read "The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas" if you haven't. Not because it's actually required reading for this story - I think it stands on its own more or less okay - but because it is a classic for a reason.

---

Initially, no one is quite certain of what they’ve found when the Animus breaches the next manifold layer. This is in and of itself expected, of course. Exploring psychspace is by its very nature an unpredictable venture. Each of the various infinite layers is unique and bizarre in its own way, reflecting the archetypal underpinnings of an entire species present, past, or future across an infinitude of possible realities. The crew of the Animus, therefore, has seen things so utterly alien and inexplicable that only the rigors of their training and the care put into their psychic warding saved them from insanity.

It is somewhat disappointing, then, to find that this sub-domain is just a city. Definitely not Terranic, certainly not, but still following the Terranic modality, with no more than a seven-degree quantum drift.

“Towers,” Thromby says into the recorder as they sit at their post at the nose of the Animus’s command center. “Following the standard skyscrape pattern. Unclear if they’re domiciles or business centers or both. Coastal city, bay appears to be oceanic rather than lake. Pleasing blend of urbanization with natural setting.” They glance at Vigil. “Anything on the lifescope?”

Vigil shakes his head. “Nothing. It’s empty. Totally empty.”

“That’s odd,” Katrina speaks up from the helm. “The city doesn’t show signs of decay or reclamation by nature.”

“Entropy may not work in the usual way in this sub-domain,” Teasha reminds her. “The city itself could be the natural growth, reclaiming the artificial countryside. We’ve seen things like that before.”

Thromby feels Katrina’s unconscious bristling at the subtle reminder that she is the newest member of the crew and thus less experienced in the vagaries of psychspace than everyone else. Next to Vigil, who is only nineteen, she is also the youngest. “I would expect,” Katrina says, her voice cool, “that in a sub-domain so obviously based on human archetypes, entropy and nature-versus-civilization tropes would function more or less as usual.”

“I’m certain you would,” Teasha replies, her voice equally cool. “When you’ve been at this as long as me and Thromby, you’ll learn better.”

“Enough of that,” Thromby says before Katrina can reply. They love Teasha, but she tends to be too harsh on new crewmembers. A defense mechanism, they know, to insulate her from the all-too-common pain of losing them. But Katrina has too much to prove. The clash is natural and to be expected, and even useful at times, but now is not one of them. “Vigil, get me readings on atmosphere, microbiome, and psychic radiation, if any. Katrina, pick a spot on the coast and bring us down there. I want to see if the ocean is actually an ocean or a liminality representation. Teasha, get the Animus tuning to this sub-domain’s resonance frequency. I don’t want any dissociation issues.”

The orders are mostly unnecessary, since everyone already knows what they’re about, but they serve their intended purpose, which is to re-focus everyone on the task at hand and redirect their nervous energies, particularly Katrina’s. Thromby still isn’t sure she’s going to make the cut after this expedition is over, but there’s potential there. They would be foolish to ignore someone with Katrina’s strength of identity grounding.

There are plenty of sub-domains out there where it’s useful to be entirely certain of who you are, and not everyone can be.

---

The first day’s worth of exploration yields more questions than answers, which is normal and expected. Thromby is indeed certain that Katrina’s initial assumption that this is a human-archetypal sub-domain is correct. Human atmosphere, human shadow- and ontological concepts, Terranic fish in the very-real ocean. But the iconography is sparse and mostly nonsensical. It’s clear that the city was able to actually function as a city, but it feels purposeful, designed, in a way that actual cities outside psychspace rarely do.

“It’s a metaphor,” Vigil says as they sit around a campfire on the beach after the first day.

“Well, obviously,” Katrina agrees, and Vigil lights up – both visibly and psychically – at her concordance. Thromby knows Vigil has been nursing burgeoning feelings for Katrina since she joined them, and has so far seen no need to make anything of it. “But a metaphor for what?”

“We don’t have enough data,” Vigil replies. “But I’m certain of it. We just need to keep exploring.”

Thromby takes a bite of the fish they’ve been roasting over the fire. It’s a pleasant change of pace to be able to eat something real, instead of the platonic nourishment suggestions dispensed by the Animus. “Agreed. I’m curious to see what the point of this place was. We have five more days before we have to resurface and the expedition has been quite successful already. I think we can spare the time. Teasha?”

Taking a bite of her own fish, Teasha purses her lips as she chews. “I concur, but I’m uneasy.”

Teasha is their psychometry specialist, so this makes all of them sit up a little straighter. “Are we in danger?” Katrina asks.

“Of course we’re in danger, we’re in psychspace. But in this particular sub-domain? Metaphorical danger, as Vigil says. Ideological or memetic patterning rather than physical.”

Thromby nods. “I suspected that might be the axis of it, here. We will need to split up to cover the necessary ground in the time we have left, so everyone stays in contact while exploring. Mechanical and psychic. No exceptions.”

None of them are particularly happy with this pronouncement, but they see the wisdom of it. It’s distracting and somewhat draining to keep a four-way psychic connection going, especially over distance, but their implanted transceivers sometimes don’t function properly, depending on the sub-domain. Electromagnetism and causality both seem to be standard here, but such things have been known to change in an instant depending on whether the sub-domain is actively malicious or not.

Thromby doesn’t feel any such malice here, though. That doesn’t mean it isn’t present; such things are often quite good at hiding themselves. But they’ve been exploring psychspace for seventy-eight years subjective. They’ve learned to trust their instincts.

---

Two more days of exploration are frustratingly unrevealing. The city is the size of a proper metropolis, and they know it will be impossible to actually explore any significant percentage of it in only a few days, but Thromby is still irritated by their lack of progress. They find evidence of cultural signifiers, rituals, and traditions, but again, the iconography is vague and appears opaque to standard Jungian-Jingweian analysis.

Teasha spends the two days on a different investigative track than the rest of them. “Psychometrically speaking the city is remarkably healthy,” she said on the morning of their second day. “Most locations, metaphorical or otherwise, bear the echoes of trauma or strife, but this place seems to have been almost entirely peaceful. Totally voluntary anarcho-communism or ordnung-socialism, perhaps, without the usual markers of systemic violence inherent to capitalistic or fascistic systems. But there’s a thread somewhere that I keep detecting the edges of.”

“A thread of what?” Thromby asked.

“Pain, of course.”

It is on the evening of their third day in the city that Teasha calls them to her. She uses their transceiver link rather than a psychic summons. “To avoid contamination,” she explains. “I’ve found the source of the thread. Double your usual wardings and enter seclusive patterning before you come inside.”

Thromby does so, of course, though they dislike cutting themselves off from their extrasensory perception. It feels like trying to see with only one eye. When they arrive at Teasha’s location, however, they immediately understand why she insisted on it. The possibility of psychic contamination here is very high.

“What is this?” Katrina asks, holding her nose in disgust.

“The point of the metaphor, of course,” Teasha replies. She indicates the filthy cellar in which they’ve found themselves, the only part of the city so far that has seemed actively decrepit. “I guarantee you that even if we spent the rest of our lives exploring this city we would find only this one place showing any signs of entropy.”

The cellar stinks of excrement, a combination of ammonia and fetid shit, despite the physical processes creating such smells having terminated long ago. The floor is dirt. There are no windows. In one corner there are two mops, their heads stiff with drying waste, and a bucket, the metal bands around its circumference orange with rust.

“They concentrated all of the city’s entropy into a single space?” Vigil asks.

“Not entropy,” Teasha tells him. “Cruelty.”

Katrina gapes, her hand falling away from her nose for a moment. “Come again?”

“Something lived here,” Teasha explains to her. “Or, more precisely, was forced to live here. It functioned as a psychic magnet, of sorts. The functioning of the city relied entirely upon its imprisonment and use as a scapegoat.”

“What was it?” Vigil asks.

“One of the innocence-sacrifice archetypes. An animal or a child. I suspect a child; an animal can feel pain and misery, certainly, but it doesn’t conceive of injustice in the same way a child does.”

Thromby feels their stomach turn a little. “Ah. I see.”

“See what?” Katrina demands.

“The point of the metaphor indeed,” Thromby replies. “This entire city and all its inhabitants, predicated on the suffering on a child. It’s a morality construct, and a good one, too.”

“A good one?” Vigil asks. “It’s grotesque.”

“Your deontological leanings are showing,” Katrina tells him. “From a utilitarian perspective it’s perfect. Nothing exists without imposing an energy burden on the system in which it exists. Even the nourishment suggestions the Animus feeds us in liminal space between manifolds is distilled from universal krill. But this? The concentration of all of a society’s utility burden onto a single individual. The ultimate maximization principle.”

“And your teleological leanings are showing,” Teasha sniffs. “You’re missing the point of the metaphor entirely, Katrina. It isn’t about utility. It’s about cruelty. The cruelty is the point.”

Katrina’s nostrils flare and Thromby cuts in before she can start really arguing. “Enough,” they say. “A conflict here in this space could be dangerous. We’re at the focus of the sub-domain and things have a way of rippling. We’ve discovered the point of the metaphor, so we can go back to the Animus and leave in the morning.”

Both Katrina and Teasha look ready to argue the point with them, but then they master themselves and both nod.

“Do we have to wait until morning?” Vigil asks, looking around the cellar in transparent disgust. “I would prefer to leave sooner rather than later.”

“You know the rules,” Thromby replies. “We don’t transit without everyone being rested. A tired mind is a vulnerable mind.”

Reluctantly, Vigil nods, too. The four of them walk away from the cellar, their thoughts opaque to one another.

---

Thromby is jolted out of sleep by Teasha screaming.

They sit bolt upright and look down at Teasha in the bed next to them. She is clutching at her head, shaking, writhing beneath the sheets. “Teasha!” Thromby snaps. “Focus! Center yourself!” They grab her by the wrists and pry her hands from her face; her nails are leaving bloody marks in her skin.

“Too much, it’s too much!” she shrieks. “I’m lost!”

Thromby forces their way into her mind. She previously gave them her consent for this, knowing that it might be necessary in a moment like this one. What they see there –

“Aquinas,” they say aloud. The implants in Teasha’s cochlear nerves pick up on the trigger word and activate, sending the kill-signal to other implants deeper within her brain. She stops screaming and slumps, unconscious, temporarily brain-dead. When Thromby says the word again she will be switched back on, but for the moment she is safe from the psychic contamination that was attacking her along her psychometric vector.

Which, of course, means that Thromby has to deal with this issue alone.

They dress quickly and exit the Animus into a beautiful summer day. Pennants and banners wave atop the rigging of ships in the harbor, bells sound from the city, and people, so many people, cavort and revel on the beach, in the waves, in the streets. There is laughter, merriment, the intoxicating psychic swell of happiness and excitement. Thromby threads their way through the crowds in the streets – mothers carrying their infants, children running through the streets in elaborate games of some variation of Terran tag, huge parades of horse-drawn carts with animalistic balloon totems floating in the air above them. Vendors call out to Thromby, offering delicious food, intricately made jewelry, amazing clockwork-mechanical toys, sensory-enhancing drugs, and a thousand other variegated temptations. Street musicians play upon cunningly crafted instruments – strings, pipes, percussion, keys – and revelers cavort to the tunes.

Thromby can feel the bright sparks of all of these people in their mind. These are real, thinking, feeling beings. They belong to the metaphor, certainly, but Thromby could speak to them, touch them, verify their self-consciousness and interiority, even invite them to come and join them onboard the Animus and explore psychspace. They could bring them up into the real, return home with them, have a life with them. That is how it has to be, of course. Thromby knows they themself may belong to a different metaphor of a different order, after all. The real is only real because enough people agree it is.

But they do none of these things. They just walk, stolidly, back to where they know they have to go.

Katrina is waiting for them outside the cellar, barring the way in. Thromby has their wards up at triple strength and has been in seclusive patterning since before leaving the Animus, but they don’t need to be psychic to read her mind. Everything she is feeling and thinking is there in plain sight – the proud and defiant way her chin is thrust out, the blaze in her eyes, the way she has her arms crossed and feet at shoulder width. She is ready to fight.

“Let me through,” Thromby says without preamble.

“No.”

Well, that’s their respective positions, Thromby thinks, articulated clearly and easily enough. “Why not?” they ask.

“Vigil consented.”

“Vigil is in love with you and you know as well as I do that consent is a matter of framing,” Thromby snaps. “Move.”

“No. I explained everything to him and he consented. It has nothing to do with whatever feelings he might have for me.”

“That’s bullshit and you know it, but fine. For the sake of argument, tell me how you explained it.”

Katrina hesitates, and Thromby can tell she wasn’t expecting them to actually offer her a chance to proselytize. “The point of the metaphor is that no matter how great and beautiful the society, if it’s predicated on cruelty, it’s unjust,” she says. “Deontological thinking, obviously, but cruelty is by definition nonconsensual. I explained to Vigil that if he allowed it, we could collaboratively put blocks in his mind, purposefully regress him to a childlike mental state, and put him in the cellar to suffer for a specific length of time. Then we can pull him back out, remove the blocks, and even erase the memories of the trauma. The child-Vigil won’t, can’t, consent, but it also won’t exist for more than a day, and pragmatically speaking never will have.”

Thromby massages their temples. “Congratulations. Once again, you have missed the point of the metaphor.”

“Damnit, Thromby, I’m not a child! I have the same training and grounding in theory that you and Teasha do. Everything I’m doing is teleologically sound, and Vigil agreed that with the steps we’re taking –”

“You’re trying to outsmart it,” Thromby cuts her off. “That’s how I know you’ve missed the point. You can’t outsmart this, Katrina. There is no perfect set of circumstances you can construct to get around the simple fact that this city functions, exists, because of deliberate and terrible cruelty. That’s the entire point of it, just like Teasha said. Teasha, who, by the way, is currently in a coma. I had to put her into it to keep Vigil’s misery from damaging her.”

“It’s a thought experiment,” she argues, obviously not addressing the point about Teasha because she knows she won’t win that argument. “There’s always a correct answer for them. The trolley, the Gettier, the –”

“It’s about fucking sin,” Thromby sighs.

“Are you joking right now? You’re going back to the religious well?”

“Yes, because that’s what’s happening right now. The city is a sin, Katrina. The excesses of its beauty, its wonder, its perfection, are obscene precisely because of how and why they function. It’s rooted in the ideology of disgust and taint. Utility, teleology, all of these justifications and rationalizations exist and have their use, but at the end of the day, answer me one question: will you trade places with Vigil?”

Katrina hesitates.

It’s only a bare moment, less than a second, even, but it’s there. And Thromby sees it, and Katrina sees it.

“Yes,” she says, finally.

“I knew that would be your answer. But you know that the answer doesn’t really matter, does it?”

Katrina lowers her head. “No.”

“You know why you hesitated.”

“Yes.” She looks back up at them. “But – there’s no such thing as absolute morality, any more than there’s a single objective reality.”

“Of course there isn’t. And yet, you hesitated.”

They just lock eyes for a few seconds. Then she lowers her gaze again. “And yet, I did.”

Thromby steps past her and opens the cellar.

#writing#my writing#story#short story#short stories#creative writing#omelas#the ones who walk away from omelas#ursula k leguin#leguin#science fiction#sci fi#sci-fi

144 notes

·

View notes

Text

[in the smouldering ruins of omelas] well well. look who finally came out of their room.

85 notes

·

View notes

Text

SHORT STORY TOURNAMENT - FINALS

THE CASK OF AMONTILLADO by Edgar Allen Poe (1846) (link) - tw: death

“I drink,” he said, “to the buried that repose around us.”

THE ONES WHO WALK AWAY FROM OMELAS by Ursula K Le Guin (1973) (link) - tw: child abuse

Do you believe? Do you accept the festival, the city, the joy? No? Then let me describe one more thing. In the basement under one of the beautiful public buildings of Omelas, there is a room. It has one locked door, and no window. ... In the room a child is sitting.

THE YELLOW WALLPAPER by Charlotte Perkins Gilman (1887) (link) - tw: depression, insanity

John is so pleased to see me improve! He laughed a little the other day, and said I seem to be flourishing in spite of my wall-paper. I turned it off with a laugh. I had no intentions of telling him it was because of the wall-paper — he would make fun of me. He might even want to take me away.

#short story tournament#literature#the cask of amontillado#the ones who walk away from omelas#the yellow wallpaper#edgar allen poe#ursula k le guin#charlotte perkins gilman#fiction#short stories#tournaments#finals#polls

91 notes

·

View notes

Text

You've gotta give Doctor Who credit for having multiple episodes that understand that the point of Omelas isn't to stay in Omelas, or leave Omelas, but to save the child.

#random thought of the day#doctor who#the ones who walk away from omelas#magpie brought to mind snw's omelas episode#(which was the direct inspiration for my sleeping beauty take on it last year)#(cuz i was ticked at how they handled it)#(though i didn't watch the whole thing cuz content)#and since then i've thought a lot about how dw does it right#it's quite satisfying

88 notes

·

View notes

Text

A lot fewer people have been walking away from Omelas ever since we swapped out our load-bearing tortured child for a more efficient model. Now instead of one child being kept in perpetual pain and misery we have it spread out between twelve kids at a time, each of whom only have to spend about a week feeling kind of itchy and tired

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

On Individualism and Collectivism

I saw a post promoting collectivism over individualism going around a while back, which inspired me to write a post about a philosophical issue I've been thinking about for a while. I was going to reblog a version of that post with some interesting commentary added, and add even more commentary to it, but it was getting incredibly long, so I thought it was best to make my own post, and just include a link -- here -- to the post with the relevant commentary, to which I will occasionally refer in the discussion below.

I got into a disagreement a few years ago with another academic philosopher about whether feminists must be individualists, in which I attempted (unsuccessfully, I'm afraid) to explain a distinction between what I have since started calling surface and fundamental individualism and collectivism:

Surface individualism or collectivism describes the emphasis of the cultural ethos that members of a society are taught.

Fundamental individualism or collectivism refers to where the fundamental locus of ethical value is taken to lie: the individual or the community.

Here's my overall thesis, fully explained and argued for under the "keep reading" link (which may be similar to what @reasonandempathy was trying to get at in the first reblog comment on the post linked above):

Surface collectivism is probably better than surface individualism because it promotes the well-being of more people; but fundamental individualism is necessary to justify the protection of individual rights to autonomy over one's life and body.

Neoliberal individualism is surface individualism. The culture emphasizes individual choice, individual action, makes individuals feel like they must always support themselves and rely on no one else, tells them that that is what constitutes real "freedom." This is the outlook that the other philosopher was (correctly) arguing is wrongly thought, by some white Western feminists, to be necessary to feminism; it is sometimes promoted by Western aid agencies that encourage women in the Global South to start their own businesses to achieve financial independence from (apparently) oppressive family and community structures. Surface collectivism would mean a culture that tells people to always think about their relationships with others, how they are embedded in a community, what they can accomplish by working with others. That sounds a lot better, especially to those of us who are well-acquainted with the pernicious, alienating consequences of surface individualism.

Fundamental collectivism says that only the collective matters in itself, or has intrinsic value, and any given individual has significance only a means to the survival and flourishing of the collective. It's ambiguous, but this seems to be the attitude being articulated in the tweet at the top of the linked post. And that is what @conservativemalarkey talks about in the third comment on that post as a justification for forcing anyone born with a uterus and ovaries to give birth: according to fundamental collectivism, that person's reproductive capacities are in the first instance a resource for the community to reproduce itself, and their individual preferences about what to do with their body do not matter. There is no individual right to bodily autonomy; there is only the duty to perpetuate the community. To put it in the terms that @nothorses brought up: the collective has rights but no obligations/duties to its individuals; individuals have obligations to the collective, but no rights that it is required to respect.

That's why I have come to believe (and was attempting to argue with the other philosopher) that fundamental (not surface) collectivism is incompatible with feminism: it provides no grounds to protect individuals' rights to bodily autonomy. That, of course, harms everyone; historically, communities have often forced men and boys to risk their lives going to war to defend the community, or to add to its wealth and territory. But it especially notably harms those who are assumed to have the capacity to gestate and bear children (gendered by cisnormative society as women and girls, giving rise to sexism and misogyny that affect anyone associated with that category), because that capacity is, so to speak, the "limiting reagent" for reproduction in the community: it is a scarce resource, far more limited in the lifespan, costly in time and energy, and dangerous to the life and health of the possessor than the capacity to fertilize. For that reason, patriarchal societies (incredibly widespread historically and geographically) effectively regard the reproductive capacities of potential child-bearers as community property, or as a commodity regulated by the community. A (presumed) woman*'s value, and the purpose of her life, consists in her ability to reproduce within the socially approved constraints; women's sexual activities are everyone's business; everyone feels entitled to comment on the bodies of women of reproductive age, especially when pregnant, and how they raise their children.

[[*Meant to encompass anyone perceived as a woman, which in most contexts, historically, also means being assumed to have childbearing capacities; includes AFAB people who do not identify as women as well as trans women who pass as cis. The general attitude also, of course, affects trans women who don't pass as cis but are understood to be communicating a self-identification as a woman.]]

Can a community be said to flourish if a large number of the individuals in it are miserable? Structurally, yes: it can successfully perpetuate itself, grow, become wealthy, while all its individuals dutifully sacrifice themselves to it. Ironically, for a society based so heavily on surface individualism, modern capitalism looks a lot like that: individuals are expected to sacrifice themselves for The Economy, which grows and maintains itself like an organism without regard for whether the vast majority of the individual 'cells' that make up its organs and tissues are satisfied with their lives. This is also true of patriarchal cultures in which at least half of the population is limited in the way they can live their lives, and are taught to see this as natural and inevitable.

Fundamental individualism, by contrast, says that the locus of value is the individual: what matters is the well-being of individual human (or sentient) beings, and communities are valuable only insofar as they contribute to the well-being of their individual members. Fundamental individualism is perfectly compatible with surface collectivism, and it is very probably true that most individuals will be happiest if they live in communities that emphasize their communal ties and encourage them to think of themselves as enmeshed in and dependent on a community. BUT fundamental individualism will say that this kind of culture is good because it is what is best for the greatest number of individuals.

According to fundamental individualism, the collective, qua collective, has no value independent of the individuals in it. Individuals have rights to autonomy and to have basic needs met which the community must respect. Do individuals have obligations to the collective? Yes, but only as a surface shorthand for their obligations to all the other individuals that make it up. Communities, cultures, collective forms of life have no intrinsic value, because they are not independently sentient: they cannot feel pain, pleasure, desire, or satisfaction. The loss of communities and cultures is terrible because of the harm that it causes to the individuals who lose their sense of connection, identity, and purpose. But if a way of life systematically fails to promote the well-being of a great many of its members, and/or systematically violates their rights in a way that cannot be remedied without ending that way of life, then it deserves to be ended. Again, most of us here have no trouble saying that about modern capitalist society, but it's equally true of any form of social organization.

Are people (outside of academic philosophy) generally familiar with Ursula K. Le Guin's story "The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas"? Here's the text, available from libcom.org (short for "libertarian communism," apparently). Spoiler alert: episode 1.06 of Star Trek: Strange New Worlds, "Lift Us Where Suffering Cannot Reach," is very obviously based on it. That is one of the starkest, most evocative illustrations of collectivism that is not balanced by consideration of the rights and well-being of individuals: one individual is forced to live in unending misery so that the rest of the community can be happy.

"But that's not real collectivism!" someone will protest. "Real collectivism means everyone takes care of each other! They would have compassion for every member of the community and never allow that to happen to one of them!" Well, it depends on what you mean by "real." Many forms of surface collectivism could mount an argument against that arrangement, on the grounds that a healthy community must care for all its members, even (or especially!) the humblest and most vulnerable. From the perspective of either surface or fundamental collectivism, it might be argued that permitting any member of the community to suffer in this way would damage the cohesion of the community by encouraging callousness regarding the suffering of (certain) other members.

But nothing about fundamental collectivism says that a community must care for all its individual members in order to flourish; on the contrary, it says that individuals do not matter for their own sake, but only for what they can contribute to the community. Fundamental collectivism can only offer an indirect, instrumental argument that allowing the Omelas situation would harm the community because of how it would affect the community ethos. In Le Guin's story, all members of the community do know about the condition of their society's thriving; that's how some of them decide that they should walk away. But in the SNW episode, most people do not understand what their happiness rests on; they can blissfully believe that the community does care for all its members, so fundamental collectivism could not find anything wrong with the arrangement.

Crucially, fundamental collectivism cannot capture the real reason most of us will think the Omelas situation is horrifying: that it violates the rights of an individual who does not choose to sacrifice their well-being for the sake of the community, but is forced to suffer so that the community can thrive. If you're thinking it would be OK if, and only if, the individual did choose to be the sacrifice for the community: that's something that might be promoted, even glorified, by surface collectivism, which would encourage people to see their individual happiness as less important than the well-being of the community. But fundamental collectivism could not account for the profound ethical difference between a chosen and a forced sacrifice: the importance of individual autonomy; the principle that no one should be able to make such a momentous choice about the course of an individual's life except that individual.

Mind you, this does not mean that a fundamentally individualistic ethics will necessarily rule the Omelas situation impermissible. There are some forms of fundamental individualism that could justify it -- notably, utilitarianism, which would say that the suffering of one individual, however appalling, is far outweighed by the perfect happiness of thousands or millions of other individuals. Fundamental individualism is not sufficient to rule it out; and you might not think it should be ruled out, considering the numbers involved. But fundamental individualism is necessary to even say what the problem is. The only objection that fundamental collectivism could offer doesn't even locate the problem in the terrible forced suffering of the individual, but in the way that knowing about it might affect the cohesion of the rest of the community.

So while I'm generally in favor of a surface-collectivist ethos, I'm convinced that any fundamentally collectivist ethical theory has profoundly immoral consequences. The ultimate locus of ethical value must be the individual. It's fine for a culture to encourage individuals to prioritize the community over themselves, but there is something genuinely wrong with the community forcing sacrifices on its members, and that can only be accounted for with reference to irreducible individual rights.

#individualism vs collectivism#individualism#collectivism#ethics#moral philosophy#philosophy#the ones who walk away from omelas#snw spoilers#snw 1.06#snw 1x06#lift us where suffering cannot reach

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

"'The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas' is a work of almost flawless ambiguity.

At once universally applicable and devilishly vague, Ursula K. Le Guin’s 1973 short story examines a perfect utopia built around the perpetuation of unimaginable cruelty upon a helpless, destitute child. It spans a mere 2800 words and yet evokes a thousand social ills past and present, real and possible, in the mind of the reader — all the while committing to precisely none of them.

Is it about income inequality? Unequal treatment under the criminal justice system? The tension between extractive bourgeois and extracted proletariat? Any one of these would feel simplistic in the face of the story itself, which bucks and weaves between gentle fable and pointed taunt, never quite allowing the reader to get their footing, leaving them to marinate in unease and uncertainty over what somehow feels like a pointed accusation despite never — quite — being spoken aloud.

One moment Le Guin dwells on rich descriptions of the Omelans’ happy lives (parades, horses with braided manes, jolly flute music), the next she interrogates the reader about whether they believe the utopia laid out before them is even possible, while hinting darkly at the revelation to come. And once the titular 'ones who walk away' do appear — those unhappy Omelans who, once they know the horrible secret, can no longer stomach their utopia and wander off into the desert in desperate search of something else — it is not to give the reader relief or a sense of shared triumph over a cruel system, but to simultaneously implicate us for our own inactions and remind us that moral righteousness alone is not enough to guarantee happiness and success.

'Omelas' is a masterpiece, a fable that is all the more gripping for its puzzling lack of moral. But this powerful ambiguity is at the heart of both the story’s staying power and its strange ability to confound both readers and other writers — a pointed refusal to provide an easy answer that makes the story so good, so lasting, and so effective, and yet simultaneously such a broad target for misguided interpretations and bad-faith criticism alike."

- Kurt Schiller, from "Omelas, Je T'aime." Blood Knife, 8 July 2022.

#kurt schiller#ursula k. le guin#quote#quotations#the ones who walk away from omelas#short stories#literature#storytelling#fantasy#ambiguity#activism#inequality

118 notes

·

View notes

Text

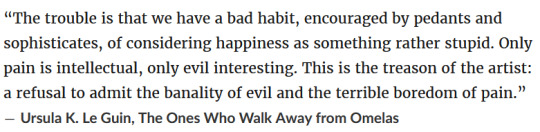

artsy suffering

i stumbled upon "the ones who walk away from omelas" by ursula k le guin today and read this wonderful quote once more:

now, the short story is (*obviously*) about way more than that, but this particular sentiment always tugs on me. whether it's gently deconstructed as a longing for a reason...

sourly (bitterly?) laughed at,

or just cheekily parodied

i just need to be reminded that making evil and pain out to be a noble experience is, in and of itself, fucking lame.

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

Omelas

"The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas"

By Ursula K. Le Guin 1973

This haunting short story is about a city that can be a utopia only if a single child suffers. You will forever be thinking about this story after reading it.

Fun fact, she chose the name from a passing road sign. Salem O (Oregon) spelled backwards. This story is very much grounded in colonized Oregon's long history of utopia projects (that all eventually fizzle out, many after becoming dangerous cults).

"Why Don't We Just Kill The Kid In The Omelas Hole"

By Isabel J. Kim, 2024

Kim tells the story of what happens if the suffering child of Omelas is killed. Outstanding new story that powerfully examines Omelas vs. our world.

"The Ones Who Stay and Fight"

By N. K. Jemisin, 2018

Jemisin's rebuttal to "The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas" about a society that achieves utopia through honoring all people as having inherent worth. It asks the reader why that sounds so impossible.

#Ursula K. Le Guin#Omelas#The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas#Isabel J. Kim#Why Don't We Just Kill The Kid In The Omelas Hole#N. K. Jemisin#The Ones Who Stay and Fight

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

Things in my ask box #2

Got a new one for the “questions that might catch the poster some flak” bin. The poster asks, “What were you thinking when you wrote ‘The Ones Who Stay and Fight?’“ There was more to the question, but that’s what it boils down to (and I did clarify with the ask-er that this is what they wanted to know most).

I don’t generally like to discuss readers’ interpretations of my stories. Art is subjective, and what one person loves another might loathe, sometimes for the exact same reasons. Also, half the time I don’t even know what I’m doing; sometimes I don’t notice a theme in my work until years later when a reviewer mentions it, or I re-read it long after publication. My mind works in mysterious ways, even to me. But since you asked what I was thinking and not to confirm/deny a particular interpretation, I’ll try to explain.

(First, for those who haven’t read it, Ursula K. Le Guin’s “The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas” is her most famous short story, and probably one of the most famous short stories in the world. There’s a whole subgenre of responses to it, because it provokes such powerful reactions in readers, and I’m no exception. [I’m a huge fan of Le Guin, if you didn’t know from me screaming about her to anyone who would listen for like 10 years now.] If you haven’t read the story, you should; it’s probably available somewhere online. There are a million ways to interpret the story, and if you poke around for reviews or lit crit analyses you’ll find feminist readings, anti-capitalist readings, mythopoeic/folklorist readings, and more. My story does not make sense if you haven’t read her story; it functions solely in conversation with Le Guin’s. Think of it as fanfic, if that helps.)

I’m not a literary scholar and I don’t pretend to be, but I’ve always leaned into the anti-capitalist reading of “Omelas.” Anybody who’s reading this in the developed world is already living in Omelas. Every time we buy a pair of Nikes, we’re contributing to sweatshops, child labor, migration crises, pollution... our own version of the abused child locked in a cellar. No ethical consumption under capitalism. Also, I lean anti-capitalist with “Omelas” because I think often of this quote by Le Guin:

“We live in capitalism. Its power seems inescapable. So did the divine right of kings. Any human power can be resisted and changed by human beings. Resistance and change often begin in art, and very often in our art, the art of words.”

Bad. Ass. I want to be her when I grow up.

That said, when I decided to respond to this as a writer -- by writing back to it -- I was more interested in anti-racist readings of Omelas. Those interpretations don’t seem to be as popular, but at the time I wrote my story, I was trying to process the absolute bombardment of open racism and every other kind of bigotry that seemed to be metastasizing in the wake of Trump’s election. I pondered the world that these people seemed to want: a world of war and endless suffering, doomed to end in extinction for us all (tho some believe Jesus or Jeff Bezos will whisk them away before things get too bad). I wondered what it would take to come back from that world, if we went down that path but managed to survive as a species. So to my mind, Omelas works well as a metaphor for conservatives’ (and fascists’) endless fantasies of the world that was, in which everything was wonderful before the “corruptions” of liberalism destroyed it -- corruptions like equality, diversity, intellectualism, religious freedom, and democracy. This is the “again” that the “make America great...” people embrace -- a “better” world that never existed. We all know that in the 1950s, there were plenty of kids in cellars, worse than today: BIPOC kids, queer kids, disabled kids, poor kids. If America’s wealthy and powerful get what they want, they will get to live in a utopian fantasy; the rest of us go in the cellar.

The society these people want is one that further-codifies the idea that some people are lesser. Some people aren’t as fully people, basically, and therefore don’t deserve rights, basic necessities, compassion, or life. Therefore I decided to make my “utopia” (scare quotes because, like Omelas, Um-Helat really isn’t) an anti-bigoted society, which has instead chosen to codify the idea that no one is lesser. Instead of its happiness depending on limited oppression, I wanted my “utopia” to depend on limited suppression of that insidious idea.

Suppression is no better than oppression, by the way. We’re used to oppression, so maybe it doesn’t seem so bad... to some. But both ways of maintaining these not-quite-utopias require harm to be done to some for the benefit of others. Omelas chose to limit the harm to a random child, and to a lesser degree to all its citizens, who must morally compromise themselves in order to enjoy their lives. Um-Helat chooses to limit the harm to those who’ve internalized some people are lesser -- the intolerant, per Karl Popper’s paradox of tolerance -- and to the “social workers,” who must morally compromise themselves in order for the other citizens of Um-Helat to thrive. I was also playing with the idea that there’s nowhere to walk away to. Imperialism and capitalism have made pretty much the whole world Omelas, in real life. So how does any society grapple with its own complicity with evil? Omelas is better off than our own world, and Um-Helat, because people can walk away, there.

It’s entirely possible that I failed to do what I tried to do with this story -- first because I tried to do so much. “Omelas” is a deceptively simple argument with deep, complex points being made; my attempt to answer had to cover a lot of territory. Second because Le Guin was a master of the short form, while I’m pretty much a dabbler, and third because this was also my first time trying pastiche, and it probably shows. But I believe in shooting my literary shot, hit or miss, and I’m glad that I did. It turned out better than I expected.

So that’s what I was thinking. ☺️

#damn it these always get so long#clearly I've missed longform blogging#answered asks#short fiction#the ones who stay and fight#the ones who walk away from omelas#Ursula K. Le Guin

131 notes

·

View notes

Text

Don't nuance me, if your answer is ultimately yes or no, then it's still yes or no. Just explain yourself in the tags.

#for my own answer i wouldn't necessarily conscientiously object to Omelas or anything.#torturing that child sucks but it is just that one child and i think i could stomach it compared to what it would allow for Omelas#i dont think it applies on the same level as any sort of broader discrimination. its not a group of people#its just some kid.#however!#i dont want to live in a utopia anyway. i think Omelas would bore me.#and so my answer is ultimately yes.#the ones who walk away from omelas#dystopia#utopia

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Short Story Tournament

THERE WILL COME SOFT RAINS by Ray Bradbury (1950) (link) - tw: death

Eight-one, tick-tock, eight-one o'clock, off to school, off to work, run, run, eight-one! But no doors slammed, no carpets took the soft tread of rubber heels. It was raining outside. The weather box on the front door sang quietly: "Rain, rain, go away; umbrellas, raincoats for today. .." And the rain tapped on the empty house, echoing.

THE ONES WHO WALK AWAY FROM OMELAS by Ursula K Le Guin (1973) (link) - tw: child abuse

Do you believe? Do you accept the festival, the city, the joy? No? Then let me describe one more thing. In the basement under one of the beautiful public buildings of Omelas, there is a room. It has one locked door, and no window. ... In the room a child is sitting.

#short story tournament#there will come soft rains#the ones who walk away from omelas#ursula k le guin#ray bradbury#literature#fiction#short stories#polls#semifinals

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

Answer as honestly as you can, and explain your answers in the tags if you want

#poll#the ones who walk away from omelas#ursula k. le guin#literature#literary poll#utopia#dystopia?#tumblr polls#omelas

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Narrator wanted to found Omelas and the Contrarian would choose to walk away

There is a short story by Ursula K. Le Guin called ‘The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas’. You can read it here or listen to it here.

The basic summery is that Omelas is a wonderful city. People are happy, kind and intelligent. The arts and science are celebrated and people can pursue their passions. There are no kings, police or army because they aren’t needed.

However, for all this to work, one child is locked in a basement. They are frightened, abused and underfed. Everyone knows that the child is there and they all accept it. The child must suffer so that everyone else can be happy.

If the child leaves the basement or is ever shown any kindness at all, then the good fortune and happiness of everyone in Omelas ends. Omelas would become like any other city. Instead of one child suffering and everyone else being happy, most of the population would suffer so that – like in the real world – 1% of people could have their every whim satisfied.

Everyone in Omelas knows that the child is there. A lot of them go to see the child but even those that don’t know the child suffers for them to be happy.

Sometimes, someone in Omelas will go quiet for a few days before they leave Omelas forever. Where they go to no one knows, it is a place even less imaginable than Omelas.

Anyway, the point of all this is that the Narrator is trying to turn the universe into Omelas. One person has to suffer so that everyone else can be happy. Unlike the child in the original story, the Princess wouldn’t even have to suffer for very long. She would die and then everyone else would be saved.

I think the Contrarian would be one of the people that walk away from Omelas. He thinks everything is all fun and games and enjoys annoy people. However, the moment he realises that his actions have actual consequences and that the Princess is being hurt by them, he stops and wants to help.

I think, if he was in Omelas, since he couldn’t save the child, he would choose to leave rather than be part of the reason the child has to suffer. For the same reason, if he had to slay the Princess to ensure everyone else’s happiness or save her a damn everyone else, I think he’d choose to leave. Even if he can’t save her, he wouldn’t want to be one of the people she had to suffer for.

#slay the princess#slay the princess spoilers#spoilers#stp contrarian#stp narrator#The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas#Ursula K. Le Guin#It's a very good short story about the problems of Utilataranisum#The greatest good for the greatest number#Would you walk away?#We live in a world where almost all of us ARE the child suffering so that a few can benefit#But if things were reversed would you opt out and walk away so that you weren’t part of the reason someone had to suffer?#YOU can’t save the child but if everyone walks away then the child doesn’t have to suffer#Obviously that wouldn’t work in the world of Slat the Princess because only the Long Quiet gets to make the choice#But still#Unrelated but I always wondered if the child in the original story was real#The story repeatedly asks you to believe in Omelas#Before mentioning the child#Then asks if NOW you believe#Can outsiders only believe in Omelas if they think someone is suffering?

23 notes

·

View notes