#the plummery

Text

new drawing!!!

now I really want to put this on a shirt...

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

William Playfair the Scottish engineer and political economist was born on September 22nd 1759.

In a day where anniversaries are thin on the ground, thank god for William Henry Playfair.

I read one article about Playfair that describes him as "a kind of Forrest Gump of the Enlightenment" perhaps a bit harsh, I would say he was a bit of a polymath, another source in my opinion is more accurate, Playfair is without doubt to many of you out there "the most famous man you have never heard of" he rubbed shoulders with the era’s many giants, switching careers at the drop of a hat, and throwing himself headlong into history-changing events, from the storming of the Bastille to the settling of the American West.

William had a lot to live up to, his brothers were architect James Playfair and mathematician John Playfair, his father passed away when he was 13 and it was left to John to lead the family. After serving his apprenticeship with Andrew Meikle, the inventor of the threshing machine, Playfair became draftsman and personal assistant to James Watt at the Boulton and Watt steam engine factory in Soho, Birmingham then seems to have just wander from one trade to another, the way Gump wandered through life, so you can see where the analogy comes from.

William Playfair, was, during his adult life, (takes a deep breath) a millwright, engineer, draftsman, accountant, inventor, silversmith, merchant, investment broker, economist, statistician, pamphleteer, translator, publicist, land speculator, convict, banker, ardent royalist, editor, blackmailer and journalist. Okay they are not all jobs, but they do put you in the picture a wee bit on the character of the man I think.

Most interestingly in my opinion was his time as a spy in France during the Revolution and was on the scene during the storming of the Bastille. He even helps trigger the first major political scandal in the newly formed United States, a land speculation gone bad involving Washington, Hamilton, and Jefferson.

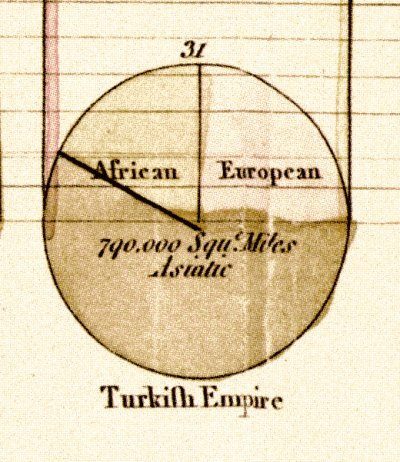

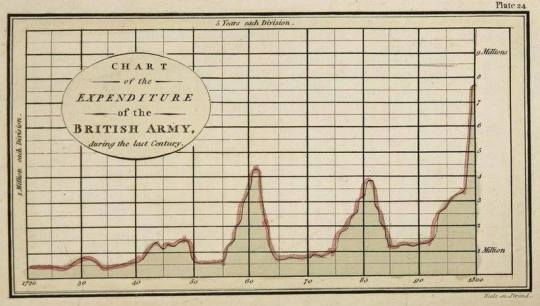

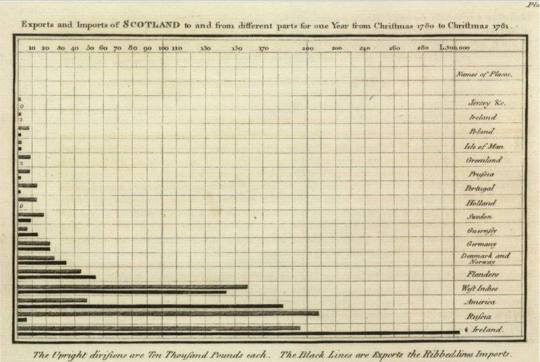

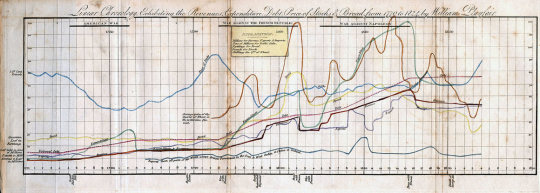

To go into all of this man's adventurers would take too long, instead I will just tell you that the one thing he did, that has been a part of all your lives, in one way or another, is he invented the graph. Before William invented the graph you had to read through pages of statistics to find things out, the graph, you "get it" in a glance. In 1786, he published The Commercial and Political Atlas, a compendium of bar and line charts representing different European countries’ imports, exports, wages, and other trends for which he had the data handy. As the man himself explained, “Men of high rank, or active business, can only pay attention to outlines… It is hoped that, with the Assistance of these Charts, such information will be got without the fatigue and trouble of studying the particulars.” he went on “No study is less alluring or more dry and tedious than statistics, unless the mind and imagination are set to work,” in the book’s introduction.

His old boss Watt, was sent a copy of the Commercial Atlas for review, and wasn't impressed, called the book “mere plummery” and its author “a Rascal.”

To finish I must say that he was a rather humble man and actually gave credit for the invention to his brother writing, “[John] taught me to know that whatever can be expressed in numbers, may be represented by lines,” Playfair wrote much later, in the introduction to one of his books of diagrams. “To the best and most affectionate of brothers, I owe the invention of [these] Charts.” He was never a success in his lifetime and was seen as a ditherer by Watt, William Playfair died in 1823, in poverty and relative obscurity, banned from any good society.

Slowly, over the next century or so, the supply of readily available data grew—as did the the public’s appetite for it. Bar, line and pie charts began trickling into newspapers and textbooks. Two hundred years later, as we barrel forward into the Information Age, you can’t click a link without stumbling upon some kind of data visualization. The next time you come across a graph, remember, like many other notable inventions in our history, take pride in that it was the work of a Scot that gave us these easy to read information "pictures".

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Permaculture in a tiny urban garden: the Plummery of Kat Lavers.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The genus Andrias has the largest living amphibians and is where King Andrias got his name.

#amphibia#king andrias#amphibians#extinct#paleontology#fossil#diplocaulus#andrias#seymouria#prionosuchus plummeri#andrias scheuchzeri#geology#natural history#salamander#giant salamander#extinct amphibians#Philip Steele

93 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Growing an Abundance of Food in the City Using Permaculture

I first stumbled across this video on the ultra wonderful Treehugger.com (a morning ritual for me to scroll through while sipping on some coffee) and felt so inspired I went home and started planting my little seedlings. While I am currently renting and my landlord is a bit picky on “ripping up sod” (there’s no sod in my yard, but if that’s the only thing they get picky on I’ll make moveable beds) I can’t say I don’t want this for my future home. The idea of hanging out with plants in my backyard makes me happier than the idea of a lawn I have to constantly mow.

The Plummery is a great goal, one that I am so excited to keep watching and trying to make a dream into a reality for me.

#gardening#silvopasture#permaculture#australia#treehugger#urban gardening#self reliance#prepper#life goals#inspiration#how can I do this?

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Growing a years' worth of produce on 1000 sq. ft in 4 hours a week The Plummery is an experiment. The results of that experiment look good. From a 23 year old forest garden to a 1 acre permaculture farm, Happen Films have brought us many beautiful videos about people growing food on whatever land they have available. Their latest is no exception.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

📚BOOK REVIEW 📚 The Plummery Collection By Merry Sparrow ____________________________________ Check out the All Book Reviews title found in the 🔗 link in my bio to view my full review & to get your own copy. ______________________________________________ Please continue to protect each other by practicing #socialdistancing and supporting businesses by ordering takeout & using online options to order merchandise. ____________________________________________ #supporteachother #supportauthors #literature #kaybeesbookshelfreview #kaybeesbookshelf #instagram #word #story #bookstagram #blogger #literatura #pages #writers #romance #booksofinstagram #fiction #blackauthors #booklovers #bookshelf #explorepage #explore (at Westside, Houston, Texas) https://www.instagram.com/p/CBcF1E6DBhS/?igshid=1gehf5si0q3gl

#socialdistancing#supporteachother#supportauthors#literature#kaybeesbookshelfreview#kaybeesbookshelf#instagram#word#story#bookstagram#blogger#literatura#pages#writers#romance#booksofinstagram#fiction#blackauthors#booklovers#bookshelf#explorepage#explore

0 notes

Photo

Inspiring Woman Growing a Huge Amount of Food in a Tiny Backyard in the City The Plummery is a suburban home where a tiny urban permaculture garden measuring only 100sq/m (1076 sq feet) produces over 400kg/900 pounds of food year-round... Source:

0 notes

Link

The Plumary: the finest in loamy, mixed, semiactive, mesic, aquic hapludults

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

0 notes

Photo

William Playfair the Scottish engineer and political economist was born on September 22nd 1759.

I read one article about Playfair that describes him as "a kind of Forrest Gump of the Enlightenment" perhaps a bit harsh, I would say he was a bit of a polymath, another source in my opinion is more accurate, Playfair is without doubt to many of you out there "the most famous man you have never heard of" he rubbed shoulders with the era’s many giants, switching careers at the drop of a hat, and throwing himself headlong into history-changing events, from the storming of the Bastille to the settling of the American West.

William had a lot to live up to, his brothers were architect James Playfair and mathematician John Playfair, his father passed away when he was 13 and it was left to John to lead the family and his education.

After serving his apprenticeship with Andrew Meikle, the inventor of the threshing machine, William Playfair became draftsman and personal assistant to James Watt at the Boulton and Watt steam engine factory in Soho, Birmingham then seems to have just wander from one trade to another, the way Gump wandered through life, so you can see where the analogy comes from.

William, was, during his adult life, (takes a deep breath) a millwright, engineer, draftsman, accountant, inventor, silversmith, merchant, investment broker, economist, statistician, pamphleteer, translator, publicist, land speculator, convict, banker, ardent royalist, editor, blackmailer and journalist.

Okay they are not all jobs, but they do put you in the picture a wee bit on the character of the man I think.

Most interestingly in my opinion was his time as a spy in France during the Revolution and was on the scene during the storming of the Bastille. He even helps trigger the first major political scandal in the newly formed United States, a land speculation gone bad involving Washington, Hamilton, and Jefferson.

To go into all of this man's adventurers would take too long, instead I will just tell you that the one thing he did, that has been a part of all your lives, in one way or another, is he invented the graph. Before William invented the graph you had to read through pages of statistics to find things out, the graph, you "get it" in a glance.

In 1786, he published "The Commercial and Political Atlas" , a compendium of bar and line charts representing different European countries’ imports, exports, wages, and other trends for which he had the data handy. As the man himself explained, “Men of high rank, or active business, can only pay attention to outlines… It is hoped that, with the Assistance of these Charts, such information will be got without the fatigue and trouble of studying the particulars.” he went on “No study is less alluring or more dry and tedious than statistics, unless the mind and imagination are set to work,” in the book’s introduction.

His old boss Watt, was sent a copy of the Commercial Atlas for review, and wasn't impressed, called the book “mere plummery” and its author “a Rascal.”

To finish I must say that he was a rather humble man and actually gave credit for the invention to his brother writing, "John taught me to know that whatever can be expressed in numbers, may be represented by lines,” Playfair wrote much later, in the introduction to one of his books of diagrams. “To the best and most affectionate of brothers, I owe the invention of these Charts.”

He was never a success in his lifetime and was seen as a ditherer by Watt.

William Playfair died in 1823, in poverty and relative obscurity, banned from any good society. Slowly, over the next century or so, the supply of readily available data grew—as did the the public’s appetite for it. Bar, line and pie charts began trickling into newspapers and textbooks. Two hundred years later, as we barrel forward into the Information Age, you can’t click a link without stumbling upon some kind of data visualisation.

The next time you come across a graph, remember, like many other notable inventions in our history, take pride in that it was the work of a Scot that gave us these easy to read information "pictures".

You can find more on William Playfair here https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/the-scottish-scoundrel-who-changed-how-we-see-data

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Prionosuchus plummeri, one of the largest amphibians to ever exist (estimates go from 5-9m length)

More of my art: DeviantArt | Facebook

#my art#paleo#prionosuchus#amphibian#pepe the frog#permian#brazil#extinct#animal#nature#lake#underwater#temnospondyl

12 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Incredibly Abundant Permaculture Garden in the City | The Plummery

0 notes

Text

merry-go-round of plummery

This topic was set at 2017-09-27 02:10:21

0 notes

Link

Today, graphs and charts are seen as more efficient than words, letting us gulp information rather than sip it. For a large chunk of European history, though, this was far from the case. As statistician Howard Wainer explains in Graphic Discovery, 18th century academics actually looked down their noses at anything that resembled a picture. “Readers were accustomed to persuasion by rhetorical means,” Wainer writes—well-written arguments, perhaps spruced up by a table or two, would get educated people on your side. Illustrations, in contrast, were thought of as inaccurate “trifles,” suited more for working through arguments than for presenting them. There were technical barriers as well: scientists, economists, and others who might have sketched out hasty graphs for their own edification often lacked the necessary artistic skills to engrave them into plates for publication, writes Wainer. [...] “[John] taught me to know that whatever can be expressed in numbers, may be represented by lines,” Playfair wrote much later, in the introduction to one of his books of diagrams. “To the best and most affectionate of brothers, I owe the invention of [these] Charts.” [...] Perhaps due to his lack of skill on the ground, Playfair began looking at contemporary situations through a more empirical lens. In 1786, he published The Commercial and Political Atlas, a compendium of bar and line charts representing different European countries’ imports, exports, wages, and other trends for which he had the data handy. Like many of today’s charts, Playfair’s plots juxtaposed two sets of facts in order to tell a story; also like today’s, they were designed to help busy people understand complex issues at a glance. “As the knowledge of mankind increases, and transactions multiply, it becomes more and more desirable to abbreviate and facilitate the modes of conveying information,” he explained. “Men of high rank, or active business, can only pay attention to outlines… It is hoped that, with the Assistance of these Charts, such information will be got without the fatigue and trouble of studying the particulars.” [...] Playfair realized what he’d done—“I was very anxious to find out whether I was actually the first,” he later wrote—but most others didn’t. His old boss Watt, sent a copy of the Commercial Atlas for review, called the book “mere plummery” and its author “a Rascal.” Others at the time dismissed it out of hand, “because geometrical measurement has not any relation to money or to time,” as Playfair himself detailed. Perhaps the greatest evidence of the invention’s failure to catch on was the fate of its creator—Playfair died in 1823, “in poverty in relative obscurity, banned from any good society,” writes Douglas J. Hamilton in Jacobitism, Enlightenment and Empire.

0 notes