#the sublime

Text

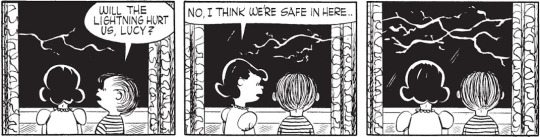

March 19, 1956 — see The Complete Peanuts 1955-1958

#peanuts#comics#humor#existentialism#lucy van pelt#linus van pelt#lightning#nature#fear#children#kids#the sublime

267 notes

·

View notes

Text

Putting freecam in my hands as a video maker is dangerous, but oh so vital.

304 notes

·

View notes

Text

Paul Thek

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hence, the more wild, fanciful, and extraordinary are the circumstances of a scene of horror, the more pleasure we receive from it; and where they are too near common nature, though violently borne by curiosity through the adventure, we cannot repeat it or reflect on it, without an over-balance of pain.

"On the Pleasure Derived from Objects of Terror," Anna Letitia Barbauld

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

And so we come again, as so many discussions of fantasy inevitably do, to J. R. R. Tolkien. As a writer of fantasy, Tolkien hardly needs an introduction. Even before the success of the film adaptations of his work transformed him into a household name, he had won first the hearts of children with The Hobbit in 1937 and, some twenty years later, the hearts and minds of adult readers with The Lord of the Rings. But, like Coleridge and MacDonald before him, Tolkien thought deeply about his craft as a writer and creator, and it is largely by virtue of this thought that his art has achieved such timeless success. His 1939 lecture “On Fairy-Stories,” subsequently published as an essay in the 1964 book Tree and Leaf, is, as the editors of the recent authoritative edition of the essay put it, “Tolkien’s defining study of and the centre-point in his thinking about the genre [of fantasy], as well as being the theoretical basis for his fiction” (Flinger and Anderson 9). In this seminal work, he addresses all the points about the imagination raised by Coleridge and, following MacDonald, defends their application in the literary arts. We have already explored the other facets of Tolkien’s theory of fantasy as it contributes to the fantastic sublime, but I have saved his thoughts on the imagination for last, because I feel they serve as a linchpin for the fantastic sublime as a whole.

At first glance it would appear that Tolkien dispenses altogether with Coleridge’s whole tripartite scheme of primary imagination, secondary imagination, and fancy. Indeed, he takes issue with the desynonymization of imagination and fancy, though he does not single out Coleridge directly. A philologist of the highest order and sometime editor of the Oxford English Dictionary, Tolkien may be displaying false modesty when he ventures that, “[r]idiculous though it may be for one so ill-instructed to have an opinion on this critical matter, I venture to think the verbal distinction philologically inappropriate, and the analysis inaccurate” (OFS 59). Having deconstructed Coleridge’s framework, Tolkien then counters with his own, which is, by his own admission, just as arbitrary as Coleridge’s imagination/fancy divide.

The mental power of image-making is one thing, or aspect; and it should appropriately be called Imagination. . . The achievement of the expression, which gives (or seems to give) the inner consistency of reality, is indeed another thing, or aspect, needing another name: Art, the operative link between Imagination and the final result, Sub-creation. For my present purpose I require a word which shall embrace both the Sub-creative Art in itself and a quality of strangeness and wonder in the Expression. . . I propose, therefore, to arrogate to myself the powers of Humpty-Dumpty, and to use Fantasy for this purpose. (OFS 59-60)

But the advantage to this approach as both a theoretical model and a critical framework is that it separates out and clearly labels the writer’s mind (Imagination), the creative process itself (Art), and the finished product (Sub-creation). Fantasy is the end result.

Although Tolkien’s theory dispenses with Coleridge’s distinction between imagination and fancy, however, it preserves and even strengthens Coleridge’s assertions regarding the qualitative similarities between primary and secondary imagination. This isn’t immediately obvious, though the term “Sub-creation” gives us a telling hint. But to fully understand Tolkien’s debt to Coleridge, we must travel back to 1931, eight years before Tolkien delivered his lecture “On Fairy-Stories.” In that year, following a latenight conversation with his friend C. S. Lewis in which he defended the truths of Pagan myth even in a Christian world, he crystalized his thoughts into a poem called “Mythopoeia.” He quotes several lines from the poem in his lecture, and they are worth quoting here as well, for they cut to the heart of the similarity between primary and secondary imagination:

Man, Sub-creator, the refracted light

through whom is splintered from a single White

to many hues, and endlessly combined

in living shapes that move from mind to mind.

Though all the crannies of the world we filled

with Elves and Goblins, though we dared to build

Gods and their houses out of dark and light,

and sowed the seed of dragons, 'twas our right. (Mythopoeia 61-8)

The metaphor of light that Tolkien employs here and elsewhere for the imaginative process is more vivid than Coleridge’s original distinction, but it nonetheless conveys exactly the same sense. In fact, the verbs Coleridge uses to describe the process of the secondary imagination—dissolves, diffuses, dissipates—suggest he was thinking along the same metaphorical lines. But Tolkien, usually so careful to avoid overt religious reference, here actually makes the religious and spiritual implications of the imagination more explicit than Coleridge’s “infinite I AM.” While, as we saw, George MacDonald is uncomfortable with ascribing to man the power of creation, Tolkien actually revels in man’s creative power. As in Coleridge, man’s creative power differs from that of God only in degree, hence the word “sub-creator.”

Tolkien’s vision of man as sub-creator leads him to openly challenge Coleridge’s willing suspension of disbelief. Like MacDonald, he argues that a secondary world, or sub-creation, must be governed by a certain consistency if it is to hold an audience’s attention. To him, “this suspension of disbelief is a substitute for the genuine thing, a subterfuge we use when condescending to games or make-believe, or when trying (more or less willingly) to find what virtue we can in the work of an art that has for us failed” (OFS 52). The true aim of fantasy, for Tolkien, is to draw the audience into a state of “Secondary Belief” similar to the sustained participative imagination argued for by MacDonald. The real change from Coleridge, and even MacDonald, here is that it places the burden of proof, so to speak, on the artist rather than the audience. When confronted with a good work of fantasy, the audience should not have to voluntarily suspend disbelief. Rather, “the story-maker proves a successful 'subcreator'. He makes a Secondary World which your mind can enter. Inside it, what he relates is 'true': it accords with the laws of that world. You therefore believe it, while you are, as it were, inside” (OFS 52). I can’t help but think that Coleridge would have admired the symmetry of this idea of primary and secondary belief with his own idea of primary and secondary imagination, and would have conceded the point to Tolkien. And it is here that the fantastic sublime comes into full flower.

Tolkien’s language here reflects many of the writings on the sublime, from Longinus all the way up to present critics like Robert Doran. There is a certain inexorable, inevitable, magnetic pull that surrounds works of the sublime like a gravitational field. The sublime grabs hold of readers and doesn’t let them go. It turns their gaze upward and pushes their minds and spirits to see and experience things they could not have otherwise imagined. And at the same time, it makes audiences see themselves from those same heights, see their own mortality and frailty, and want to climb higher, be greater, do better. But while traditional conceptions of the sublime see this process as occurring in flashes, as lightning during a tumultuous storm, Tolkien insists we can have more than that. In his view, we can actually live in a world, if only for a little while, where the sublime is made manifest, where it is as real as rain.

And like Coleridge and MacDonald before him, he insists that these sublime worlds are not merely the playgrounds of children, but the kingdoms of all readers, of any age. He is in agreement with Coleridge about the educational value of fairy-stories. While

tepidly approving of fairy tales written specifically for children, he urges that “it may be better for them to read some things, especially fairy-stories, that are beyond their measure rather than short of it. Their books like their clothes should allow for growth, and their

books at any rate should encourage it.” But Tolkien is adamant that fantasy or fairy stories (he uses the terms more or less interchangeably) should be read by everyone. “If fairy-story as a kind is worth reading at all it is worthy to be written for and read by

adults,” he says, for “they will, of course, put more in and get more out than children can.” (OFS 58).

Tolkien delivered this lecture about two years after publishing The Hobbit, and just as he was beginning to work in earnest on The Lord of the Rings. While the former book is clearly a book for children, the latter effort “grew in the telling,” as he notes in the foreword to the second edition. Fortunately for the reading world, he practiced what he preached in “On Fairy-Stories.” But he did not build this world on sand. Tolkien scholars point to the medieval sources for Tolkien’s world, and rightly so, for these are indeed his secondary world’s bones and sinews. But its life-blood is, I would argue, the imaginative laws... that both create and sustain it. He took his own advice to heart and created a secondary world, Middle Earth, that has captivated and captured the imagination of millions of readers, drawing them into a state of secondary belief that, in some cases, lasts long past the reading of the books.

#Tolkien#Tolkien studies#J.R.R. Tolkien#the sublime#literary criticism#samuel taylor coleridge#suspension of disbelief#George MacDonald#the fantastic sublime#fantasy literature#fantasy genre#on fairy-stories#mythopoesis#mythopoeia#secondary belief#sub-creation

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

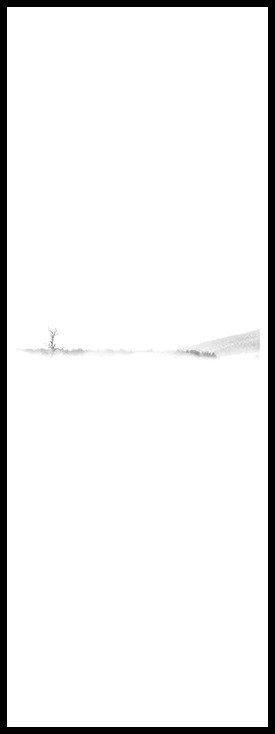

Genetic Drift in Landscape #10 © Steve Cordingley All rights reserved.

#photography#landscape#the sublime#The New Topographics#aesthetics#philosophy#photographers on tumblr#original photographers#lensblr

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

find beauty in the ecosystem and realise you are part of that global ecosystem/biosphere -> self esteem ⬆ and regard for the natural world ⬆⬆

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

CURSE The Magnus Archives for always making me want to call the literary concept of the sublime The Vast... because that's basically what it is

#i love tma for using so many different horror tropes!!!#but also it will forever make me sort everything into the entitiy categories#tma#the magnus archives#the entities#the vast#the sublime#gothic literature

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wandering Thought # 356

A profane world, deprived of the Sacred, is a world in which beauty and ugliness can no longer persist, for these derive their very nature and existence from the Sublime, which is itself the avenue of the Sacred. In a profane world, only desire persists, pleasure or displeasure, attraction or repulsion, but not Love, no longer that which allows the feeling of the Eternal to swell in our hearts and overwhelm our souls. We do not know quite yet what it is we are killing in ourselves as we detach our world from the Sacred. Our world becomes base, petty, profane, anti-spiritual, but for this lack, we can fill our souls with an endless multitude of pleasure. Yet the pleasure in its multitude will not fill the abysmal gap which opened up inside us, and which will devour us whole.

View On WordPress

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Barbie+Oppenheimer

⛰⛰ | Try visiting Twin Peaks sometime. It’s located at the intersection of Camp & the Sublime. PLUS, they have great coffee & pie.

____________________

#twin peaks#twin peaks memes#memes#barbenheimer#barbie#oppenheimer#lynchian#david lynch#mark frost#Camp#the sublime#sublime#Horror#Horror Movies#atomic weapons#double feature#film#movies#tv#television

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Imagine being in the 18th century, and you just buried your loved one, hoping and praying to god that their soul would be safe.

Now imagine what is basically a college dropout scavenging your great aunt bertha’s nose from the charnel house. His purpose is to create the first zombie ever.

Now also imagine that your great aunt bertha’s nose belongs on a giant child that’s going on a murder rampage-

#mary shelly's frankenstein#Frankenstein#victor frankenstein#charnel houses#18th century#your great aunt berthas nose#gothic#gothicism#death#dead#the father of all zombies#franky#the monster derserved better#dark academia#dark#the sublime#romantisism#Frankenstein is a bad father

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

In 1973, [Randy] wrote more extensively on these feelings while stationed at McClure Meadow, his most cherished meadow in the park. There, he sensed he was “close to something very great and very large, something containing me and all this around me, something I only dimly perceive, and understand not at all.”

“Perhaps,” he pondered, “if I am here, aware, and perceptive long enough I will.”

[...]

And then he said, matter-of-factly, “The least I owe these mountains is a body.”

–The Last Season, Eric Blehm

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bella and Edward’s Relationship and Romance/the Gothic

Image by Caspar David Friedrich, Woman Before Rising Sun, ca. 1818, oil on canvas (Wikimedia Commons)

SUMMARY

In the world where Bella and Edward live, they are hallucinations instead of visions. In the world where the are characters in a fictional tale, Bella seeing Edward in New Moon are projections of her strongest desire and visions are vivid mental images made of impressions from physical faculties (sight, hearing, tastes, etc.), so Bella's hallucinations are "visionary" in that sense.

Bella's hallucinations (because they are hallucinations and not visions at all) are only auditory in the book New Moon. Bella mentions repeatedly that she knows that these are hallucinations--she welcomes them nonetheless because they allow her to sense Edward even if she knows her subconscious is supplying this to her during her "withdrawal" stage. It continues a theme in the first book, where Eddie says to her that her blood/presence is like a drug of sorts, tempting him to drink and destroy her to experience the best spiritual-physical feeling he'll ever have as a vampire. They are each other's "drug" and temptation as well as each other's only saving grace. As Meyer writes it.

For Bella-as-tweaked-Romantic character, Edward is with the wondrous "otherworld" of vampires, werewolves, and strange "gifts", the extremity of emotions and the height of energy that this world brings to someone as fragile yet stubborn and yearning as Bella is. Because Bella is meant to be a character who achieves some sort of inner, spiritual completion through her transformation into a more powerful being. That’s the artistic vision.

Bella is a strange person in that she is conscious of how dumb and possibly self-destructive most of the things she does for Edward are. As a character, she is willing to risk that self-destruction on the belief that her Jesus-like lover will pull her through or that she will experience his transcendental presence.

One thing about the Gothic and Romantic genres is that both deal with themes of experiencing something called "the Sublime" or otherworldliness. The "sublime" is "the quality of greatness, whether physical, moral, intellectual, metaphysical, aesthetic, spiritual, or artistic. The term especially refers to a greatness beyond all possibility of calculation, measurement, or imitation." To do so means that you've gained a sort of supreme, independent power and/or finally satisfies the ever-curious or/and return to a state of eternal, complete contentment/happiness. Edward is sublime to Bella, and Bella is sublime to Edward.

#twilight#bella x edward#edward x bella#the gothic#the sublime#the romantic#the romantics#european literature#american literature#british literature#new moon#eclispe

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Genetic Drift in Landscape #09 © Steve Cordingley All rights reserved.

#photography#landscape#minimalism#the sublime#aesthetics#philosophy#photographers on tumblr#original photographers#lensblr#rural

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

After watching the film, “The Taste Of Things,” the only word that comes into mind is, sublime. Oh how quick I would watch a prequel story that takes place years before this beautiful film 😌

#if you watch this film you may know what I mean about wanting to watch a prequel ;)#the sublime#the food oh my goodness 👍#the taste of things#films

1 note

·

View note