#the wrong house: the architecture of alfred hitchcock

Text

The Wrong House The Architecture Of Alfred Hitchcock : Steven Jacobs : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Murder Artist: Alfred Hitchcock At The End Of His Rope by Alice Stoehr

“Rope was an interesting technical experiment that I was lucky and happy to be a part of, but I don’t think it was one of Hitchcock’s better films.” So wrote Farley Granger, one of its two stars, in his memoir Include Me Out. The actor was in his early twenties when the Master of Suspense plucked him from Samuel Goldwyn’s roster. He’d star in the first production from the director’s new Transatlantic Pictures as Phillip Morgan, a pianist and co-conspirator in murder. John Dall would play his partner, homicidal mastermind Brandon Shaw. Granger had the stiff pout to Dall’s trembling smirk.

The “interesting technical experiment” was Hitchcock’s decision to shoot the film, adapted from a twenty-year-old English play, as a series of 10-minute shots stitched together into a simulated feature-length take. This allowed him to retain the stage’s spatial and temporal unities while guiding the audience with the camera’s eye. In the process, he’d embed a host of meta-textual and erotic nuances within the sinister mise-en-scène. Screenwriter Arthur Laurents (Granger’s boyfriend, for a time) updated the play’s fictionalized account of Chicagoan thrill killers Leopold and Loeb to a penthouse in late ‘40s Manhattan. There, Phillip strangles the duo’s friend David—his scream behind a curtain opens the film—immediately prior to a dinner party where they’ll serve pâté atop the box that serves as his coffin. It’s a morbid premise for a comedy of manners, and Brandon taunts his guests throughout the evening. (Asked if it’s someone’s birthday, he coyly replies, “It’s, uh, really almost the opposite.”)

Granger deemed the film lesser Hitchcock due to two limitations. One was the sheer repetition and exact blocking demanded by its formal conceit, the other the Production Code’s blanket ban on “sex perversion,” which meant tiptoeing around the fact that Brandon and Phillip—like their real-life inspirations and, to some degree, Rope’s leading men—were gay. That stringent homophobia forced Hitchcock and Laurents to convey their sexuality through ambiguity and implication; the director would use similar tactics to adapt queer writers like Daphne du Maurier and Patricia Highsmith. (“Hitchcock confessed that he actually enjoyed his negotiations with [Code honcho Joseph] Breen,” notes Thomas Doherty in the book Hollywood’s Censor. “The spirited give-and-take, said Hitchcock, possessed all the thrill of competitive horse trading.”) The nature of the characters’ relationship is hardly subtext: Rope starts with their orgasmic shudder over David’s death, then labored panting after which Brandon pulls out a cigarette and lets in some light. A few minutes later, Brandon strokes the neck of a champagne bottle; Phillip asks how he felt during the act, and he gasps “tremendously exhilarated.”

Like Brandon’s hints about the murder, the homosexuality on display is surprisingly explicit if an audience can decode it. The whole film pivots around their partnership, both criminal and domestic. In an impish bit of conflation, their scheme even stands in for “the love that dare not speak its name,” with David’s body acting as a fetish object in a sexual game no one else can perceive. The guests, as Brandon puts it, are “a dull crew,” “those idiots” who include David’s father and aunt, played by London theater veterans Cedric Hardwicke and Constance Collier. Joan Chandler and Douglas Dick, both a couple years into what would be modest careers, play David’s fiancée Janet and her ex Kenneth. Character actress Edith Evanson appears as housekeeper Mrs. Wilson, a prototype for Thelma Ritter’s Stella in Rear Window, and a top-billed James Stewart is Rupert Cadell, who once mentored the murderers in arcane philosophy.

This was the first of Stewart’s four collaborations with Hitchcock. It cast the actor against type not as a romantic hero but as an observer and provocateur, his gaze shrewd, his dialogue heavy with irony. The role presaged his work in the ‘50s, with Mann rather than Capra, emphasizing psychology over ideology. Rupert, like L.B. Jeffries or Scottie Ferguson, is rooting out a crime, and in so doing comes to seem more loathsome than the villains themselves. “Murder is—or should be—an art,” he lectures midway through Rope, eyebrow arched, martini glass in hand. “Not one of the seven lively perhaps, but an art nevertheless.” Half an hour in real time later, having seen David’s body, he flies into a moralizing monologue: “You’ve given my words a meaning that I never dreamed of!” It takes up the last several minutes of the film, with Rupert snarling from deep in his righteous indignation, “Did you think you were God, Brandon?”

Stewart was a master of sputtering, impassioned oratory, and his facility for it renders Rupert’s hypocrisy especially stark. He taught these murderers; he can’t just shrug off his culpability. The Code decreed that “the sympathy of the audience shall never be thrown to the side of crime, wrongdoing, or sin.” Every transgression reaps a punishment. The ending of Rope abides by the letter of this law, as Rupert fires several shots into the night, drawing a police siren toward the building. He sits, deflated, while Phillip plays piano and Brandon has one last drink. But none of David’s loved ones get to excoriate his killers. The one man here with no integrity, no moral authority, is the one who gets the final, self-flagellating word.

The Code forbade throwing sympathy to the side of sin, but if Hitchcock meant any character in Rope as his stand-in, it was Brandon, not Rupert. The top to Phillip’s bottom, he’s the director of the play within a film. He’s storyboarded it to perfection. Janet, realizing he’s toying with her, cries that he’s incapable of just throwing a party. “No, you’d have to add something that appealed to your warped sense of humor!” Hitchcock, who’d built a corpus of corpses, must have gotten a chuckle from that line. Whereas Phillip fears discovery, Brandon puts symbolism above pragmatism, prioritizing what Phillip dubs his “neat little touches.” He needs to have dinner on the chest, the murder weapon tied around antique books, and his surrogate father Rupert in attendance, much as the film’s director needed to shoot in long takes—not because it’s pragmatic, but because it’s beautiful. He went to great lengths for verisimilar beauty here, as Steven Jacobs details in The Wrong House: The Architecture of Alfred Hitchcock. Miniatures in the three-dimensional cyclorama seen through the broad penthouse window were wired and connected to a ‘light organ’ that allowed for the gradual activation of the skyline’s thousands of lights and hundreds of neon signs. Meanwhile, spun-glass clouds were shifted by technicians from right to left during moments when the camera turned away from the window.

Jacobs notes as well that a painting by Fidelio Ponce de León hanging on Brandon and Phillip’s wall actually belonged to the director and had previously hung in his own home. Rope is avant-garde art wrapped in a bourgeois thriller, about avant-garde art wrapped in a dinner party, pushing moral and aesthetic boundaries while collapsing any distinction between the two. In this nested construction, Brandon the murder artist becomes a figure of auto-critique or perhaps apologia. Did you think you were God, Alfred? By 1948, he’d already made dozens of films, often obliquely about sex and violence, across decades and continents. He’d become the world champion sick joke raconteur. Rope is a reckoning with the ethics of his genre.

By 1948, the world had changed. A few years earlier, Hitchcock’s friend (and Rope co-producer) Sidney Bernstein had asked him to advise on a film about Germany’s newly liberated concentration camps. As Kay Gladstone writes in Holocaust and the Moving Image, Hitchcock worried that “tricky editing” would let skeptics read its footage as fraudulent and asked the editors “to use as far as possible long shots and panning shots with no cuts.” The director took his own counsel to heart.

Rope was also his first color film, the start of his fascination with dull palettes. (A quarter-century later he’d limn Frenzy’s London with every shade of beige.) Genteel browns and grays dominate the penthouse, the hues of men’s suits. Only after nightfall does the apartment glow with, in Jacobs’ phrasing, “the expressive possibilities of urban neon light.” The dinner party takes place at the crest of postwar modernity, a world away from the camps. Here, among the East Coast intelligentsia, murder’s merely a thought experiment. When David’s father mentions Hitler, Brandon dismisses him as “a paranoiac savage.” Yet even in polite society, the evening can begin with a secret killing and end with that iniquity brought to light. “Perhaps what is called civilization is hypocrisy,” says Brandon. “Perhaps,” David’s father concedes.

In 1948, the world was changing. That year saw the publication of Gore Vidal’s landmark gay novel The City and the Pillar and the first of the Kinsey Reports. Antonioni was a documentarian about to make his first feature; Truffaut was a delinquent catching Hitchcock movies at the Cinémathèque. Rope’s amorality and pitch-black humor augur a world and a cinema that were yet to come. It’s thorny gay art through a straight auteur. The film’s last thirty seconds show Rupert’s back to the camera while Brandon sips his cocktail and Phillip plays a tune, the trio lit by flashing neon. In this denouement lie decadence and damnation, art and death, the Code-closeted past and a disaffected future.

#alfred hitchcock#rope film#rope movie#hitchcock#james stewart#farley granger#john dall#gore vidal#michelangelo antonioni#francois truffaut#frenzy film#the wrong house: the architecture of alfred hitchcock#musings#film writing#film essay#oscilloscope laboratories#o-scope labs#adam yauch#Beastie Boys

53 notes

·

View notes

Photo

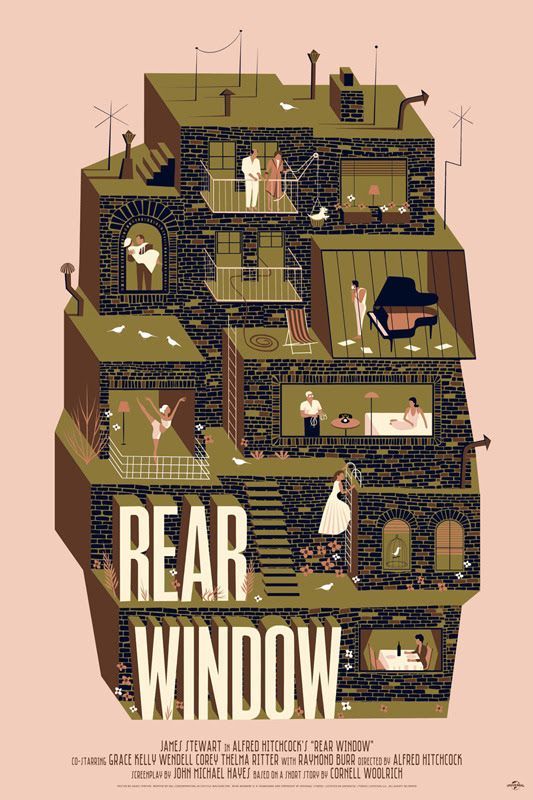

REAR WINDOW (1954) (The ultimate movie for a summer in Quarantine)

It has been said that this film evokes summer in the city like no other, and it feels particularly apt for one in which many of us have been confined to our homes. Windows in London are currently flung open due to a heat wave, and I'm finding myself much more conscious of my neighbours, of the routines of the street, and of the inherently communal nature of urban life. This emphasises the effect that climate can have on the way we experience and behave in buildings and cities - something which is often overlooked by designers.

Another aspect of being confined to an apartment is that the details of the interior, and of the limited space visible from the windows, can seem to expand to comprise your entire universe. Few of us have had as absorbing a world to observe as Jimmy Stewart does here, however, as a photographer holed up in a small Manhattan residence with a broken leg, and nothing to do all day but spy on neighbours with his telephoto lens.

Architecture often played a central role in Hitchcock's films, and several commentators such as art historian Steven Jacobs have written about this at length .He discusses the symbolism of Rear Window's set design in this essay and in the book The Wrong House: The Architecture of Alfred Hitchcock. (Poster by Adam Simpson via missedprints)

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

『白井 晟一』 - 夜の知性と夢の受肉-

*夜の知性

夜はすべてを結びつける。建築家白井晟一は、比喩的にも現実的にも(夜を徹する読書の生活)、夜を生きた者であった。そうした白井の建築には時代の、人々の、世界の夢が受肉した。

白井の建築のパトスには、同化や融合への意志がある。異質なものの同化と融合。第一に、西洋的な物質や空間への感性と、日本の建築形式の融合があげられる。また、構成の水位においての同化と融合には、エレメントの衝突と、物質への感応によるセンシュアリティなどがある。

初期の住宅の構成では、断片的なシーンがぶつかり合い、それをシンメトリーの中に押し込んだ。その結果、いびつな平面プランが出来ている。そこには、アルフレッド・ヒッチコックのセットの図面との相似が認められる。(参照文献: The Wrong House, The Architecture of Alfred Hitchcock ) 映画とは時代の夢を映す。白井の建築にはそれと同じように、象徴の直接言語による断片の集積としての夢の様相を呈する。

*同化と陶酔のディオニュソス的原理

理解の様態には「分けること」=分かること(分別知)と、「それになること」=同化(無分別知)がある。美的な状態や��識では二つの知の様態がバランスを取っている。ニーチェの言明になぞらえれば、アポロ的ディオニュソスの様態がある。白井はヤスパースに西洋哲学を学んだゆえに、その源流であるギリシアには厚い思い入れがあっただろう。また、ニーチェを深く読書しており、西洋文明の起源たる力に大いに触れたことであろう。

白井には根源への遡行がある。それが、日本的なるものの源流としての「縄文」への感応へと向かわせた。白井はその暗い原初の普遍で夢をみる。それは人類や世界すべての宿る、神話的次元の夢である。

*夢の受肉

白井は、煥乎堂についての文章において、「建築家は施主の夢を占う」と書いている。人々の潜在的な願望=夢 を感じ取り、神に代わりその世界を実現させるのが Architect という西洋文明が人間に与えた職能である。人びとは夢の中で自らの真実の姿を見る。芸術はいつも理想への郷愁というかたちで予感される。

秋の宮役場(1952)や、松井田町役場(1956)はともに地方の自治体における庁舎建築である。白井は、秋の宮役場の仕事を終えた後で、「もし自分の仕事を通じてこの地方の人々に明るい冬を過ごさせ、わずかな燃料であたたかな仕事をしてもらえることができるとすれば、都会の大きな規模の建物をつくるために働くよりはるかに楽しいことに違いないと思うようになった。」と書いている。ここには人々に対する全幅の信頼がある。善照寺(1958)は、浮遊する純粋な形態の建築物であり、内部には静謐な光が満ちている。これは浅草の人々の日々の暮らしの中で、心のよすがとなるものであろう。これら建築作品には、人々の希望に満ちた明るい夢が感じられる。

そのように、白井建築は西洋の受容を求められた日本的感性の時代当時のひとびとの夢の受肉なのだ。

そしてそれは、悪夢もはらむ。原爆堂(1955)である。原爆堂はアンビルドの建築であるが、どこまでも克明なドローイングの強度はすさまじいものがある。建築家の鈴木了二は、原爆堂について触れて、世界の分断的状況が白井において像を結ぶことが、白井晟一の建築史における積極的意義であると述べている。

白井晟一には、人類のみる明るい夢も、または悪夢も、ともに透徹した眼差しで見つめた澄んだ人間愛が宿っている。そうして人間とは矛盾した存在であるから、そのような姿勢を貫くことには多くの苦悩も伴っただろう。

夢の受肉としての建築。ニーチェの『悲劇の誕生』において引用される、ハンス・ザックスの『マイスター・ジンガー(職人詩人)』の中での言葉をあげて文章を閉じたく思う。

君、夢解きこそ

詩人の仕事だ。

人間の一番真実な思いは

夢のなかであらわれる。

すべて詩歌の道は

夢ときに他ならない

0 notes

Text

Book of the Day #208

The Wrong House; The Architecture of Alfred Hitchcock, 2003, Steven Jacobs for nai010, Rotterdam, NL.

This is right up my street, combining my interests in Alfred Hitchcock and architecture...I’ve posted before about the spatial (architectural) constraints that Hitchcock set himself in relation to filming on trains...Hitchcock uses the shape and movement of the train to amplify the feelings of anxiety and suspense that attach to the narrative.

https://bagdcontext.myblog.arts.ac.uk/2011/05/28/the-trains-of-alfred-hitchcock/

This book extends the same approach to the buildings in Hitchcock...and in relation to how spaces, shapes and surfaces form the semiotic spectacular of cinema. There’s an obvious debt to The Cabinet of Dr Caligari (1920).

I liked how the lettering on the spine and cover relate to each other...

See also my previous posts in relation to

The spatial aspects of the famous shower scene from Psycho

https://paulrennie.rennart.co.uk/post/171962264735/7852-documentary-psycho-shower-scene-alfred

Hitchcock and art

https://paulrennie.rennart.co.uk/post/150539016345/hitchcock-and-art-edward-bawden/amp

Hitchcock and speed

https://paulrennie.rennart.co.uk/post/105615335175/alfred-hitchcock-speeds-up-the-thirty-nine-steps

Hitchcock and suits

https://paulrennie.rennart.co.uk/post/188301274600/things-i-like-cary-grants-suit-to-catch-a

0 notes