#they were robespierre's political enemies

Text

When politics gets involved in history (French Revolution part)

As a general rule, when politicians meddle in history, it often creates confusion. Today I will talk about how they handle the French Revolution.

Of course, Jean Jaures did a good job on this period, although there are naturally points to criticize. But generally speaking, our politicians allow themselves to make crude or inappropriate remarks.

There are even serious historians who fall into the trap by making political amalgamations. A few days ago, while doing research, I came across an excerpt from an article by Thierry Lentz, a respected historian, made comments in Le Figaro comparing the left-wing opposition party, France Insoumise, to the Hébertists, labeling them as vulgar. My intention on this page is not to promote France Insoumise, but to qualify the Hébertists as vulgar (I imagine he also includes the Cordeliers and the Exagérés) is not good for me (the only thing that can be qualified as vulgar is the newspaper Le Père Duchesne and Hébert's style). Moreover, what does he mean by the left's reinterpretation of the Terror? He talks about Marxist-Leninist dogma in his terms, but Lenin preferred Danton, who was not a Hébertist. Plus the Bolshevik revolution was not based on the same principles as the French Revolution. The French Revolution has democratic aspects that the Bolsheviks did not apply (I'm not saying this to denigrate gratuitously the USSR, which became Russia, let's be clear). A country that has undergone a revolution compared to another country doesn’t necessarily adopt the same principles (often because there are different contexts, different paths, etc.). And reducing the Hébertists, Cordeliers, or Exagérés to the Terror is quite reductive (I have already expressed my thoughts on the Cordeliers in one of my posts).

Moreover, in left-wing parties, from what I have observed, it is rather the character of Babeuf that is taken up, considered as the father of communism (I once met a communist who saw Momoro as a reference and another who prefer Marat), while France Insoumise is something else (we can rather place Robespierre in the radical left, but I don't think he would have been a socialist, and we can be sure he was not a communist). So why once again Thierry Lentz associates France Insoumise with Trotskyism and Marxist-Leninism for taking up Robespierre? I mean, okay, there were communists who admired Robespierre like Stellio Lorenzi, but clearly not as many as one would think.

While Lentz's expertise in French history is widely respected, such political analogies raise questions about the neutrality of historical interpretation.

Moreover, it is interesting that the fact that "La Caméra explore le temps" rehabilitated the Montagnards led to the end of the program because of the Gaullist government. Once again, politics gets involved in history and leads to very bad results.

Now it's President Macron's turn. With Stéphane Bern, the president started to explain that an edict signed in 1539 by François I imposed French as the sole language in France. However, historian Mathilde Larrère says it was the French Revolution that imposed French as the sole language on the French. Once again, politics in history can lead to bad results.

I won't even talk about certain elements of the far right who claim to be followers of Robespierre because that would be giving them publicity, and it's not my vocation.

Now let's move on to Mélenchon from the France Insoumise party, who also made significant historical errors during this period. First, in one of Robespierre's videos, he calls Marie Antoinette a "spoiled brat." Accusing the former queen of treason I understand, she gave all the information she could to the enemy, but when you hear "spoiled brat," you're passing a value judgment that has nothing to do with it. Finally, he invents a marriage of Pauline Léon, saying that she ended her life in bourgeois fashion with a Girondin.

Moreover, Melenchon explain that the extreme left of the time was manipulated by the corrupt who arrested Robespierre. Okay, there were Billaud-Varennes and Collot d'Herbois in the mix, but you can't tell me that the Plaine was part of the extreme left. Moreover, most of the elements of what was called the extreme left were either in prison, like Claire Lacombe, Pauline Léon, Jean-François Varlet, or eliminated, like Chaumette, Momoro, Ronsin, and Hébert at the time of 9 Thermidor.

Moreover, contrary to what Mélenchon suggested, Chaumette and Hébert were not part of the Enragés movement.

In the end, this is the problem when our politicians try to shape history to fit their agendas. It leads to significant inconsistencies and inaccuracies.

20 notes

·

View notes

Note

Recently in my history class, we learned a little bit about Robespierre and other stuff around him. We were told that he "had the characteristics of a cult leader", and that he got Danton, Camille and their supporters executed in an effort to stop the terror from being ended. And that he didn't want the terror to end so that he keep his power and position within the CPS. What are your thoughts on this?

ohhh anon sorry if i get long-winded and rambly bc

there's a lot to unpack here

i'll take a look at each of the claims you were told, hope this helps clarify them.

First I should clarify that by "terror" I mean the emergency measures put in place by the convention to get through the crisis. I have to clarify this bc most people think the terror was just guillotining people. Newer history books (and I mean academic ones, not school textbooks) say that calling it "the terror" its inaccurate, but that's more advanced (?) and i dont wanna confuse you with that, so I'll just keep refering it as "terror" from now on.

"had the characteristics of a cult leader"

Which caracteristics? cult leaders claim to be special chosen ones or that they have access to hidden knowledge, they seek to attract and manipulate vulnerable people so they can take advantage of them and demand complete subservience.

Is true Robespierre got an obsessive following that got to weird levels of adoration, but it was more like the parasocial following of celebrities (people get that weird with modern celebrities too). There's no proof that he exploited them economically or physically. Yes, he had an ego like every educated white man from the era, and he had a tendency to self-martyrise in his speeches, but he didn't claim to be special or that he had all the answers. However, it is a common cliché that he sent to the guillotine anyone that disagreed with him, but he didn't have the authority to do that, and he even went out of his way to save political enemies he didn't see as direct threats to the republic (ie, he opposed the arrest of twenty-two (? I think, I always see a different number tbh) girondins in may 1793).

That being said, i see where your teacher is coming from, this is an easy assertion to make if you learn about the festival of the supreme being without the historical context behind it and come to the conclusion that this guy simply made up a religion out of nowhere.

Robespierre was very spiritual and the festival was important to him, but he wasn't the one that proposed it. It was another deputy, Mathieu, that brought a project to the CPS to organize a series of civic festivals consecrated to the supreme being (more on that on Mathiez's fall of Robespierre). Robespierre was in charge of presenting Mathieu's project to the convention and made a speech defending the social utility of a state religion, so the convention approved it. Since he was president of the convention by the time the festival was scheduled, he was the one to precede it, which gave him a lot of visibility that was used against him later. The point is that while he was very invested and attached to the festival, it wasn't something he did out of a whim.

Second, the concept of deism and the supreme being was very old at that point. Both declarations of the rights of men and the constitutions of 1791 and 1793 were consecrated to the supreme being. French revolutionaries in general were influenced by enlightenment ideas about God, which affirms that the universe was created by a supreme being, but rejects organized religion. Robespierre was very religious in this sense, but he still believed in religious liberty, and the point of these civic festivals and decreeing that "the french people acknowledge the existence of the Supreme Being and the immortality of the soul" was to foment religious liberty (idk if they thought of this, but the idea of a Supreme being is so vague, anyone can project whatever God they want into it) and appease the divisions caused by decristianization.

2. he got Danton, Camille and their supporters executed in an effort to stop the terror from being ended

This only makes sense if one believes that Robespierre had complete control of everything that was happening in France at the time. The dantonists' arrest was the work of the committees of public safety and general security in conjunction. I probably should explain how it got to that point, but it's a very long and complicate story and tbh i don't have a full grasp of it myself. It was a chain of events that started with Fabre shenanigans trying to cover his tracks stealing from the liquidation of the east india company and it became a massive mess that ended up with conspiracy charges against a bunch of people including Danton.

Before that, Danton and Desmoulins were advocating for a cease of the terror (and by terror i mean the state of emergency) because they believed that, since the Vendée and federalist revolts had been repressed, it was time to go back to normal, however there still was the external conflict (against all of Europe) in one side, and the Hébertists in another. The hébertists were demanding an increase of the terror and were threatening to overthrow the government if it didn't comply. So, Robespierre thought it wouldn't be wise to end the terror right there.

Robespierre tried to defend them for a while, despite disagreeing with them over stopping the terror, but at some point the evidence against Danton became too much for him to ignore. Whether that evidence proved anything or not it's still up for debate but what matters here is that he and the committees believed it, and at that time there was a lot of paranoia around treason and foreign conspiracy, so what might have been just a case of embezzlement turned into treason etc. But no, Robespierre had hesitated a lot to sign their arrest and when he was arrested himself in 9 thermidor, he was accused of trying to defend Danton AND blamed for his death because this man can never win.

3. he didn't want the terror to end so that he keep his power and position within the CPS

This one's tricky and I'm gonna get subjective/speculative territory because, on one side, I believe he was sick of the terror and there's some "cries for help" that hint of his exhaustion, but he didn't think it should have ended right away when it was the time to end it (with the french victory in the battle of Fleurus). He was mentally deteriorated by the crisis and the conga line of treasons had made him unable to see an end to it, he kept seeing conspiracy and murder plots everywhere. But also by that time he pretty much ghosted the goverment for a month, so whatever he thought about ending the terror or not didn't matter, the goverment kept going with it and using and abusing his prairial law anyway. The goriest period coincides with his absense. You could argue that he still caused it with the prairial law, which I agree, but I think the convention, the committees and the tribunals were equally responsible. Tbh this is a can of worms and historians still fight about it, so i cant give you a definitive answer.

I don't think he would want to stay in a position that had destroyed him physically and emotionally, with people that he hated, to keep power that he didn't have anymore. Being in the CPS didn't even pay well. He said himself in the 8th thermidor speech that he valued his position as a deputy of the convention more than his position in the CPS. I see him quitting soon and staying as far away from the goverment as possible, maybe even from Paris, had he survived... But that's just my personal opinion.

Im so so so sorry for this Bible length post anon, I had many thoughts about it. I don't recommend you to fight your teacher with this info bc I'm not a historian, I'm just some guy online. However, be critical of what you learn in school (assuming it's school, if this is the first time you learn about the frev) bc it simplifies history a lot and the nuances get lost. I know this is a lot of info to take in, I hope I didn't just confuse you further.

#frev#Robespierre#This post is like... Congratulations! or sorry what happened#Genuinely sorry for the length anon

387 notes

·

View notes

Note

Robespierre has been absent from the convention and comittees for a long time. Did he still had any power when he came back? Was it useful to get rid of him besides pinpointing everything onto him?

Robespierre’s absence from the Convention started on June 12, his absence from the CPS on June 30. He did however continue to remain politically active in the time that followed as well (contrary to the idea that his withdrawal was due to him falling sick and/or wanting to isolate himself). He attended 7 out of the total of 12 meetings held at the Jacobin club (a place where his influence was still big) between his withdrawal from the CPS and his death. He had people he trusted at the head of several important institutions (René-François Dumas as president of the Revolutionary Tribunal, Martial Hermann as chairholder of the Commission of Civil Administration, Tribunals and Prisons and Claude Payan as head of the Paris Commune) and while I wouldn’t go so far as to say these guys were his lackeys or anything, I also don’t think they would have done anything they thought he would disapprove of. Robespierre also continued to sporadically sign decrees for the CPS (one on July 2, one on July 5, two on July 6, one on July 9, one on July 18 and one on July 20) and on July 23 he even attended a joint sitting between the CPS and CGS, that appears to have had as its goal to sort out the differences between him and them. Different accounts exist regarding what happened at said meeting, all of which point at Robespierre being unwilling to accept the olive branch his collegues were extending to him. But later the same day Barère nevertheless held a speech at the Convention where he renounced the idea there existed any such thing as division within the government. Two days later he held a different speech where he praised Robespierre and called for a continuation of revolutionary government. Given these statements, it feels like Robespierre could have gone back to work at the CPS like nothing had happened had he been willing to bury the hatchet instead of holding his fatal 8 thermidor speech and calling for new proscriptions the day right after Barère’s second speech.

So yes, I would say he still had power and influence by the time he held his speech on 8 thermidor. It may however have been weaker compared to before his absence (as shown by the hesitation his final speech was met by at the Convention) during which his enemies had had time to slander him among other deputies (and tbf I think there were a few who had started having their doubts about him even without Fouché whispering into their ear as well).

As for if it was useful to get rid of him… well, that of course depends on who we’re talking about. I think that, had Robespierre survived thermidor, you can still question exactly how fit he was to let run a government, but to go from there to that cutting his head off was the only useful solution would perhaps be rather drastic… I think ’I’ll leave this question for others on here who are honestly much better than me at handling questions involving so much speculation.

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

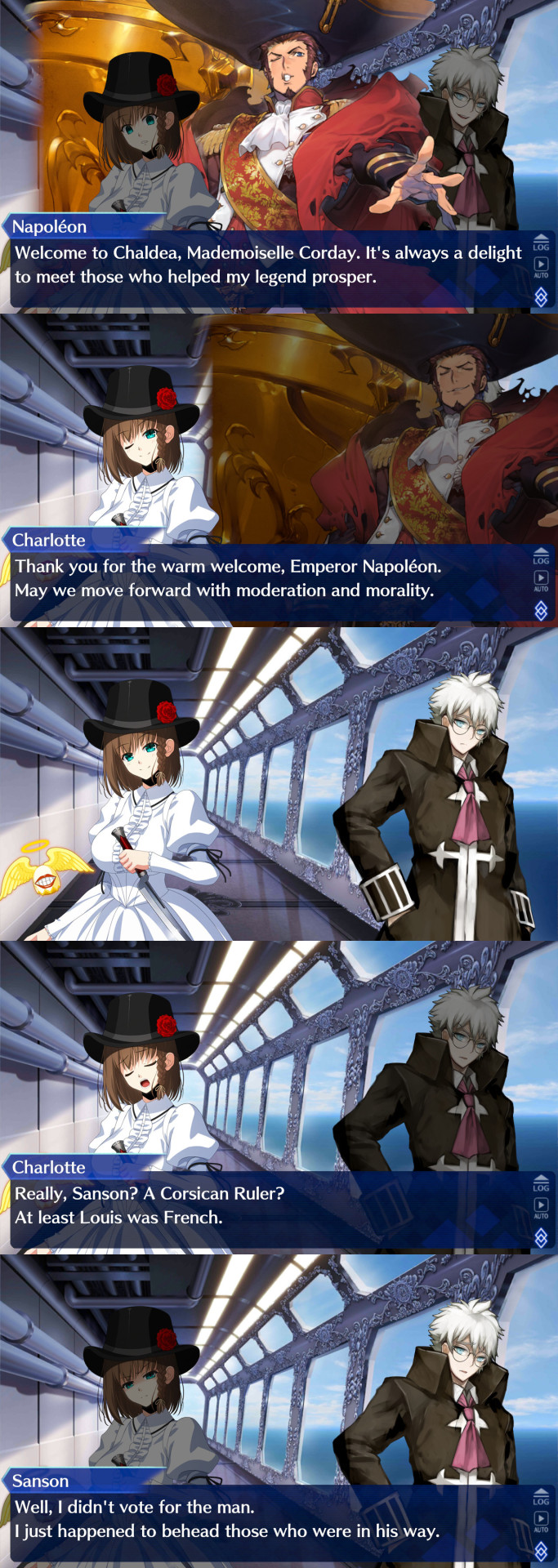

Charlotte Corday's Birthday Special: Like a Slap to the Face!

"One Death to Save A Hundred Thousand Lives, but why'd he have to be one of them?"

Commentary:

All that king and queen beheading just to put an EMPEROR on the throne through a voting system. You love to see it.

Napoleon's relationship with Corsica and France is almost as complicated as Corsica's was to the rest of Europe. Some thought it of Italy. Others thought it of France. Many agreed it was less than either.

Napoleon's political stance during his teenage years leaned towards the nationalistic with him writing a number of essays about French oppression (under Genoa, Corsica had more autonomy) and the need for Corsican independence, a sharp contrast to his more pragmatic father, Carlo.

The French Revolution not only provided more military opportunities to the young soldier, but opened him up to various political and philosophical influences as the revolutionaries schemed and quarreled among themselves as to what should be done with their country.

I'd like to think that regardless of what they thought of him, any version of Napoleon as a Servant would be crudely appreciative of anyone from his era, seeing them as little assistants who helped give him a chance of a lifetime.

Corday's political affiliation of this time was of the Girondinis, a more moderate pro-revolutionary faction who were opposed to the more radical groups who advocated for extreme enforcement of the revolution to prevent a backslide.

The assassination of Marat by Corday is thought to have been a critical factor in the stacked trial and extermination of the Girondinis (only a few months after Corday's own death), but it must be kept in mind that they were already highly unpopular thanks to Marat's writings being backed and promoted by their various rival groups such as the Montagnards.

Though how it accelerated the eventual downfall of "The Mountain" (as in, emboldening Robespierre to commit further atrocities to perceived enemies within and without) and the rise of Napoleon is disputable, Corday's murder of Marat caused the public to scrutinize the common woman – the average citizen rather than scions of nobility – as figures who would care about French politics deeply enough to martyr themselves for it.

Nothing good came from this in the short term, as the immediate reaction to this notion was to ban women's political clubs and to enact harsher punishment towards female "counter-revolutionaries".

French feminists of the moment rebuked Corday's attack, claiming that it would incite direct reprisal of some form against their movement. Exposed to their jeers and criticisms during her last four days of life, Charlotte shrugged and noted, "As I was truly calm I suffered from the shouts of a few women. But to save your country means not noticing what it costs."

Though Corday exited the world of the living with as much sanguinity and poise as she could, she suffered a posthumous indignity when one of her guillotine's carpenters by the name of Legros picked up her decapitated head and slapped it across the cheek. Some onlookers believed that her disembodied visage reacted in shock to the assault; at the very least, Charles-Henri Sanson was horrified at the insult. Legros was jailed for three months for this affront.

Charlotte Corday died on July 17. Just 10 days before her 25th Birthday.

Charles-Henri Sanson remained a largely neutral figure throughout the French Revolution. While he beheaded royals and supposed traitors to the revolution, he also did the same to the architects of the September Massacres such as Danton and Robespierre. Perhaps, in another time and place, Marat could've been one of the 2,918 executions Sanson performed.

Sanson would eventually pass on in 1806, long enough to see Napoleon's first reign come into play. It bears mentioning that "The Gentleman of Paris" had never been a big fan of monarchy

Despite the tragic – and arguably idiotic – death of Charles-Henri's son Gabriel, the Sanson legacy outlasted Napoleon's thanks to his other son Henri (the one who actually guillotined Marie Antoinette) and Henri-Clément Sanson, bringing the seven generation dynasty of executioners to a close in 1847.

Although Henri-Cléments would cash in on it immediately after his retirement due to gambling debts, tweaking and supplementing an existing apocryphal memoir of Charles-Henri written by Honoré de Balzac for a lucrative rerelease under a different title. Not as well-known a hustle as how he sold one of the original guillotines to Madame Tussauds, but there you go.

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

soviet-flavoured jokes, but they are about the frev

i thank @citizen-card for making me very creative this evening, hopefully not too creative as to forget virtue altogether.

i have written 11 jokes. here they are:

at dusk, a working-class couple, being marat's neighbours, offered to arrange for the journalist to stay in their underground room, while national guards, under the command of lafayette, were likely to come to hunt down marat during the night.

upon descending to the basement, marat was saluted by the couple's child, a very young girl, armed with a pike twice her height. the child insisted that she would stay with marat in the underground, and would fight any guard who dared to break in.

"young citoyenne, your zeal is admirable, but your must calculate your moves," said marat, "it would be wiser if your parents were the ones who put up a fight against lafayette; as for you, your main task is to survive, and to grow up under the sun."

"i will certainly grow up under the sun," answered the child, who seemed rather excited, "but how do i prove that i have met the hero of the two worlds, if he dares not fight maman and papa in the world above the ground, and simultaneously, myself in the underworld?"

charette and carrier, two very fierce men, offered to teach the ways to cook eggs to robespierre, who had no experience in cooking.

charette demonstrated how to break many eggs, while promising that he would eventually make an omelette.

carrier threw eggs into deep water wells in the hope that the sun could, with enough time, boil the water in the wells, eventually giving him poached eggs.

the hen who laid the eggs came walking to robespierre, saying that charette had promised to take care of her retirement, and carrier, the education of her children.

chaumette, a very sexist man, criticised brissot for letting his wife translate works by english writers into french.

"but what are you complaining about? you want all women to stay in the kitchen," said brissot in defense, "and my beloved félicité does all her writings in our kitchen, for she produces food for the mind."

"i do not doubt that she does," replied chaumette, "but your félicité may have translated a book written by mary wollstonecraft, who, in turn, may not have been writing in the kitchen exclusively, and this mary wollstonecraft has no husband who would testify on that fact for her."

"what is jean-lambert tallien's greatest achievement?"

"living to be 27."

"and his second greatest achievement?"

"giving the prince of chimay a worthy wife."

brissot, co-founder of the society of the friends of the blacks, came across a haitian man in the street.

"sir, are you currently a violent rebel?" asked brissot.

the haitian, who did not know that he was talking to brissot, replied politely in the negative.

"have you ever been a violent rebel in the past, then, sir?" the deputy continued to ask.

"not that i know of," said the haitian, "but why do you call me 'sir'? i thought the people of the metropole go by the title 'citizen'."

"do you know, then, sir," came yet another question, "or know of, any of your fellow men, who are, or have been at any time in the past, violent rebels?"

"of all my fellow man, one jacques-pierre brissot does stand out, and i have heard that this brissot is not afraid to make enemies with all prussians and austrians, throwing away the livelihoods of many of his own countrymen if need be."

"ah, " concluded brissot, "so you are aware of the concept of violent rebellion after all. well, sir, we in the society of the friends of the blacks will have nothing to do with you; you see, we only befriend the blacks who are willing to make the first step and befriend us back."

danton said to robespierre that virtue was what he (danton) did with his wife when they were alone at night.

"really?" said robespierre, and he was pleasantly surprised, "even saint-just would not co-write my speeches and reports with me, but the citoyenne danton would do so with you? o, that is virtue indeed."

hérault, a well-versed writer before he was a conventionnel, wanted to decree in the 1793 constitution that men should not be accused in court by people using the evidence of any and all texts that they wrote before the age of 40, since younger men were closer to nature, and freedom of press was in the Declaration.

"are you trying to make us all avoid accountability," said couthon, a colleague known for being a polite contrarian, "as i am the eldest of the five people in charge of writing this constitution, and i am only 36?"

"no," answered hérault, "i just wish to see the now 39-year-old brissot tried and brought to justice, for the grave crime of attempting to flee from his patrie while the patrie is at a war that he has started, and for the graver crime of being a boring husband; i shall do all good citizens a favour simply by sparing anyone from paying more attention to brissot's writings."

lazare carnot, a mathematician who sat with the plain, was tasked by jeanbon saint-andré, the naval officer, to calculate the number of teardrops that should drown an average english fleet.

carnot took on this calculation himself, secluded himself in his study, ignored signs of affection from his close colleague claude-antoine prieur, avoided meetings for days on end, nonchalantly signed several decrees whose objectives he made no records of in writing or in mind, for a mist would not clear before his eyes, and concluded finally that he had enough teardrops in him alone, to drown not just a few fleets, but the entirety of england.

an illiterate man asked a man who could read about the difference between desmoulins and marat, both prominent journalists.

"that is not a difficult task," answered the literate man, "one is a friend of robespierre the elder, and therefore constantly defended by him; the other has barely talked to robespierre, but would often risk himself in defending him."

the robespierre siblings all announced to each other that they were getting married, and all their spouses-to-be wished to live with them. unfortunately, a revolutionary and a counter-revolutionary and a military dictator were not considered perfect in-laws of each other, so the weddings were all called off.

during the empire, philippe buonarroti, who was a jacobin and then one of the égaux, went into exile in geneva, and sustained his own livelihood by teaching music.

one day, one of buonarroti's youngest tutees came up to him, asking him about the difference between the roles of the left hand and of the right hand in playing the piano.

"my child, the left is indispensable, and does much work to set the pace and the progression," answered his tutor, "and the right is louder and more memorable to most laymen, and therefore easily parroted."

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

[Olympe de Gouges] was a Parisian playwright and pamphleteer, an uneducated one who held women’s education dear, and she was very well known. She founded women's clubs and tried to break down the exclusion of women from politics through discussion in these clubs and through her own writing and pamphleteering. As a woman, however, in line with the traditional classification and division of women, and politics, her interests have not often been perceived as political. ‘She was indefatigable in composing appeals for good causes; the abolition of the slave trade, the setting up of public workshops for the unemployed, a national theatre for women’ (Tomalin, 1977, p. 200). What does a woman have to do to be seen as political?

In ‘Nine hundred and Ninety Nine Women of Achievement’ (Chicago, 1979) it is said of Olympe de Gouges that: ‘She demanded equal rights for women before the law, and in all aspects of public and private life. Realizing that the Revolutionaries were enemies of the emancipation of women, she covered the walls of Paris with bulletins - signed with her name - expounding her ideas and exposing the injustices of the new government.’ She was sentenced to death by Robespierre, and guillotined, but not before she to demanded to know of the women in the crowd, ‘What are the advantages you have derived from the Revolution? Slights and contempt more plainly displayed’ (p. 177).

Evidently, she was quite troublesome. In 1791, in response to the Declaration of the Rights of Man, she produce her own Declaration of the Rights of Women (a strategy closely paralleled by Wollstonecraft's work and later by the women at the first Woman's Rights convention in Seneca Falls, 1848) and, 'Taking the seventeen articles of the Declaration des Droits de l'Homme and replacing whenever she found it the word man by woman, she demanded that women should have the same political and social rights as men' (Nixon, 1971, p. 81). It was also one of her convictions that marriage had failed as a social institution and should be replaced by a more just and appropriate arrangement.

-Dale Spender, Women of Ideas and What Men Have Done to Them

17 notes

·

View notes

Note

What if Lafayette endorsed the republic?

Dear Anon,

that is an idea I never contemplated so thank you for the ask!

I think that La Fayette endorsing and supporting the republic rather than the monarchy would not have changed all that much – as long as we assume that everything else happened in the same way and that everybody else behaved as they did in reality.

La Fayette abended politics in favour of a field command because he knew that he could not get further in politics. La Fayette did not get along with many of the leading figures of the day. These disputes were based on political differences but was also due to personal disagreements. Having similar or even the same political views does not guarantee a friendly relationship. La Fayette would still have clashed with the likes of Robespierre and Marat for example. Maybe these disagreements would not have been quite as fierce, but I can not imagine La Fayette and the others getting along. La Fayette was a centrist at heart and firmly positioned himself against radicalism.

The court faction was also set against La Fayette – even when La Fayette supported the monarchy, albeit a reformed one. He would not have gained their support by championing a republic.

So, even as a republican, La Fayette would have made himself influential enemies and would ultimately trade his political role for a field command. A different political mindset might have induced La Fayette to act different in the events leading up to his arrest warrant, but these events were so messy that I feel not comfortable making any predictions.

Once in prison, neither the Austrians nor the Prussians would have treated La Fayette any better if he had supported the republic (not that that they already blamed him for everything that happened.)

In short, I do not think that La Fayette supporting the republic would have changed much. He very likely would still have budded heads with the leading political figures, what in turn would eventually have forced him to leave France. La Fayette might have been able to dodge a few attacks and aimed at him but in the end, the quarrels he had were based on more than just political differences.

I hope that answered you question, and I hope you have/had a lovely day!

#ask me anything#anon#marquis de lafayette#la fayette#french history#history#french revolution#alternate history

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The cause of France is compared with that of America during its late revolution. Would to Heaven that the comparison were just. Would to Heaven we could discern in the mirror of French affairs the same humanity, the same decorum, the same gravity, the same order, the same dignity, the same solemnity, which distinguished the cause of the American Revolution. Clouds and darkness would not then rest upon the issue as they now do. I own I do not like the comparison. When I contemplate the horrid and systematic massacres of the 2d and 3d of September; when I observe that a Marat and a Robespierre, the notorious prompters of those bloody scenes, sit triumphantly in the convention and take a conspicuous part in its measures—that an attempt to bring the assassins to justice has been obliged to be abandoned; when I see an unfortunate prince, whose reign was a continued demonstration of the goodness and benevolence of his heart, of his attachment to the people of whom he was the monarch, who, though educated in the lap of despotism, had given repeated proofs that he was not the enemy of liberty, brought precipitately and ignominiously to the block without any substantial proof of guilt, as yet disclosed—without even an authentic exhibition of motives, in decent regard to the opinions of mankind; when I find the doctrines of atheism openly advanced in the convention, and heard with loud applause; when I see the sword of fanaticism extended to force a political creed upon citizens who were invited to submit to the arms of France as the harbingers of liberty; when I behold the hand of rapacity outstretched to prostrate and ravish the monuments of religious worship, erected by those citizens and their ancestors; when I perceive passion, tumult, and violence usurping those seats, where reason and cool deliberation ought to preside, I acknowledge that I am glad to believe there is no real resemblance between what was the cause of America and what is the cause of France—that the difference is no less great than that between liberty and licentiousness. I regret whatever has a tendency to compound them, and I feel anxious, as an American, that the ebullitions of inconsiderate men among us may not tend to involve our reputation in the issue.”

— Alexander Hamilton, 1793.

12 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello! I was wondering if you could talk a bit about Philippe Le Bas and what his personality was like/what he was like as a person. In the novel I'm writing about Robespierre Le Bas is a minor character in it and I want to have an accurate characterization since I'm working on revisions. Thanks!

We don't know that much about Philippe; his wife's memoirs are the best source on him, as far as I know.

I would say that he was one of the rare well-adjusted revolutionary: he is described as calm and kind. He had a beautiful singing voice. He was smitten by Babet and they were a love match. He comes off in descriptions as polite and patient, and Babet said that this is why he was paired with Saint-Just, to kind of balance each other out, but this is her interpretation I think (?) SJ and Le Bas do seem like very different people but they worked well together and were close in that period. Not to reduce Le Bas to a "generic nice guy" but that is actually a rarity during frev (to have a well-adjusted person with no notable family trauma and issues. And I mean this with love, to both Le Bas and others).

He was one of the 16 children. His younger sister Henriette was engaged (or something) to SJ, and it seems that Le Bas and Babet were rooting for this relationship and tried to make it happen. Henriette lived them during that time and when Babet was pregnant and there is a series of letters between Babet and Philippe, including one (or was it a few?) about Henriette being disappointed about SJ changing his mind/rejecting her (?) and SJ absolutely refusing to talk to Philippe about it, and Philippe was very ??? about it. There is nothing indicating in the letter that he was angry with SJ (more weirded out by SJ's refusal to discuss Henriette), but I've read somewhere (though I forgot where, or how (un)reliable it is), that Philippe was disappointed and angry with SJ and that their friendship suffered for it and never fully recovered before Thermidor. Though no idea how anyone could know this; Babet herself I believe insisted (not in her memoirs) that SJ and Henriette just had a minor disagreement and that they would have married if not for Thermidor, but not sure how reliable this is. It might be simply Babet's view of the situation. I am mentioning Henriette and SJ because we can glean a bit of Philippe's behaviour and personality through it.

Then, of course, we have Thermidor. We know Philippe was openly suicidal in days before it; he even told Babet that he would shoot her and then kill himself "so at least they can die together", only if there wasn't for their baby son. This is very sad and extreme, but I am not sure if it tells us something specific about Philippe or were all of them in the same mood. We know SJ was in a dark mood in his late notebook entries, so it is possible that all of them were thinking along those lines.

Also, let's remember that while Philippe was the only one successfully committing suicide on Thermidor, there is a high probability that others wanted to do it. Collective suicide pact to avoid execution was also seen among the Girondins, and it made sense in the context - to do it was to deny the enemies the chance to have their justice over them and to inflict the official punishment. So, in that context, I would not see Philippe's decision as his personal state of mind, and I am not sure we can conclude anything about his character through it.

More notable is the fact that he volunteered to share his friends' fate on 9 Thermidor; he and Bonbon deserve special recognition for this. It tells us about their ideals and loyalties, and that they were ready to die for them.

That's all I can think of. It's not much, but if Philippe is just a minor character, there's no problem in making him simply a "nice guy", although he was not a doormat or meek at all.

29 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Committee of Public Safety

In the French Revolution (1789-1799), the Committee of Public Safety (French: Comité De Salut Public) was a political body created to oversee the defense of the French Republic from foreign and domestic enemies. To achieve this goal, the Committee implemented the Reign of Terror (1793-1794), during which time it accumulated virtual dictatorial powers over France.

At the height of its power, membership of the Committee consisted of twelve men who ruled France for ten consecutive months, from the start of the Terror in September 1793 to the fall of Maximilien Robespierre in July 1794 (with the sole exception of Hérault de Séchelles who was executed in April). The Committee succeeded in its goal to win victories in the French Revolutionary Wars (1792-1802), which it did by enacting mass conscriptions and implementing reforms on the French citizen armies. It is perhaps most famous for orchestrating and overseeing the Terror, in which 16,594 people were guillotined across France and thousands of others died without trial.

Continue reading...

28 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Last Interview Between Louis XVI and His Family, by Isaac Cruikshank, March of 1793.

After the abolition of the monarchy and the proclamation of the French Republic in September 1792, the National Convention considered the fate of the deposed king. There was a broad consensus that Louis was guilty of treason against the nation and that he should answer for his crimes, but how he should do so became a subject of heated debate. The convention was divided between the Girodins and the Mountain. Of the two, the Girodins were more inclined to follow due process, where is the Mountain considered themselves to be acting as a revolutionary tribunal that had no obligation to adhere to existing French law. The Convention thus became a forum where Louis's accusers expressed competing notions of revolutionary justice.

The most divisive and revealing issue was whether there should be a trial at all. The Mountain originally took the position that because the people had already judged the king on August 10, when the monarchy had fallen and the king was taken prisoner, there was no need for a second judgement. They believed the death sentence should have been carried out immediately. Robespierre argued that a trial would have been counterrevolutionary, for it would have allowed the revolution itself to be brought before the courts to be judged. A centrist majority, however, decided that the king had to be charged with specific offences in a court of law and found guilty by due process before being sentenced.

A second issue, closely related to the first, was the technical legal question of whether Louis could be subject to legal action. Even in a constitutional monarchy, such as had been established in 1789, the legislative branch of the government did not possess authority over the king. The Convention based its decision to try Louis, however, on the revolutionary principle that he had committed crimes against the nation, which the revolutionaries claimed was a higher authority than the king. Louis, moreover, was no longer king but was now a citizen and, therefore, subject to the law in the same way as anyone else.

[...]

The unanimous conviction of the king did not end the factional debates over the king’s fate. Knowing that there was extensive support for the king in various parts of the country, the Girodins asked that the verdict be appealed to the people. They argued that the Convention, dominated by the Mountain and supported by militants in Paris, had usurped the sovereignty of the people. A motion to submit the verdict to the people for ratification lost by a vote of 424-283.

The last vote, the closest of all, determines the king’s sentence. Originally, it appeared that a majority might vote for noncapital punishment. The Marquis de Condorcet, for example, argued that although the king deserved death on the basis of the law treason, he could not bring himself to vote for capital punishment on principle. The radical response to this argument came from Robespierre, who appealed to “the principles of nature” that justified the death penalty in such cases, “where it is vital to the safety of private citizens or of the public.” Robespierre's impassioned oratory carried the day. By a vote of 361-334 the King was sentenced to "death within 24 hours" rather than the alternatives of imprisonment followed by banishment after the war or imprisonment in chains for life. The following day Louis was led to the guillotine.

- Brian Levack et al. (The West: Encounters and Transformations, Third ed., pages 630-631)

For further reading on regicide as an act of national cohesion and an attack on a foreign enemy, see Kevin Duong’s “The People as a Natural Disaster: Redemptive Violence in Jacobin Political Thought”

#history#France#French Revolution#King Louis XVI#execution#Maximilien Robespierre#death penalty#regicide

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

I want to make Robespierre and sj fight (but like, a fight that would end their friendship) in a small fic I'm writing. But I don't have any idea of how. What would you think would be a catastrophic way to make them fight?

SJ refuses to shave his moustache

Okay, If I were to give you a general advice, misunderstanding and miscommunication always does the thing; the conflict can be caused by something simple and be 100% avoidable, but circumstances and emotions make it escalate. It's frustrating, it can be painful especially if both characters have best intentions with each other. It can happen over a minor/almost passing situation that is simply made hard to explain and makes the other one jump to wrong conclusions; little space to hold a proper conversation, rush, stressing outer circumstances that make the conflict escalate more than it usually would.

If I were to be more specific about a possible situation leading to a fight, perhaps it could be a classic meeting with someone a person shouldn't be caught seeing! It can look like betrayal of ideals, especially if it happens after a very specific conversation. Spotted having a "secret", friendly-looking chat with a political enemy they specifically mistrusted yesterday? Accidental, but feels like backstabbing! Little tricks like this will sound cliché, but can certainly be written well ;) Especially with a background consisting of seemingly irrevelant clues that will only later make sense once suspicion raises! That's first thing that came to my head, but go wild!

#but i believe that ANYTHING can be tragic if you build it up for a while with little things and then add a trigger#Little stuff can be catastrophic#but i am not very creative that's on me sorry :(#also playing with human flaws and fears is nice!#robespierre being terribly stubborn and idealistic? turn those traits against him.#proper characterization can give you a lot already ;) what would be most triggering to them?#think of how you see them and what would trigger their worst fears#i'm not much help but I gave you my best Anon#good luck!!!#ask#anon

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

Desmoulins was the most famous journalists in the history of the French Revolution, and despite the intense competition (Hebért and Marat), Desmoulins remained at the top of his profession because of his writing talent, and the newspaper "Le Vieux Cordelier" was his masterpiece..but Did Desmoulins have competitors and enemies? (apart from his famous problem with the Committee and with Robespierre) Was there really someone who wanted to overthrow him for one reason or another? Was anyone else strongly opposed to his views other than the committee? If so, who is it ? And was this opposition one of the reasons that ultimately implicated him and led him to the end of his path in life? And who was really his opponent? (if he existed)

Throughout his career as a journalist, Desmoulins came to release four different papers — Révolutions de France et de Brabant (86 numbers released between November 1789-August 1791), La Tribune des Patriotes (4 numbers released between April-May 1792), Révolutions de France et de Brabant: Second partie (October-December 1792) and finally Le Vieux Cordelier (six numbers+one unfinished released between December 1793-January 1794).

The first one of the papers — Révolutions de France et de Brabant — saw the light of day on November 28 1789, three months after freedom of the press had been declared by the National Assembly via the Declaration of Man and of the Citizen. According to Press in the French Revolution (1971) by John Gilchrist, as many as 250 new newspapers appeared between July and December 1789, of which the majority were friendly to revolution. It goes in other words without saying that the competition to get people to listen to what exactly you had to say was big. Camille and like-minded journalists did however not turn against one another in an attempt to take subscribers for themselves, instead they viewed each other as collegues and brothers in arms that fought (or I guess wrote) side by side for their principles. Throughout Révolutions de France et de Brabant you can find Camille giving shout-outs and republishing parts from a multitude of other likeminded journalists (try searching for the names of the authors within the digitalized journals and you’ll see), most frequently l’Ami du peuple by Marat, Orateur du peuple by Fréron, Le Patriote Français by Brissot, Annales Patriotiques by Mercier and Carra, Révolutions de Paris by Prudhomme and Courrier de Provence by Mirabeau. Many of these journalists were also not only brothers in arms but personal friends, as can be seen through for example Camille telling his father that ”my two collegues Brissot and Mercier, the elite among the journalists” had been among his wedding witnesses, this letter from Fréron to Camille telling him to publish a letter of his in the next number of Révolutions de France et de Brabant and this letter from Mirabeau to Camille. While from time to time they disagreed and called each other out on certain topics, it was not until they started to really devide on a political level that their relationships completely fell apart (see for example Brissot and Desmoulins).

If rivarly between like-minded journalists was something it would appear never really was a problem, Camille still had to bear with attacks/slander from journalists who disagreed with him, his loved ones being caught up in the crossfire, as well as straight up murder threats. Some of examples of this can be seen below:

M. Desmoulins, after having done so much for his glory, thought he could think of his honor, and he resolved to marry. He was sure to create the happiness of the one he would choose for his company, and out of respect for the blood of his masters, he wanted to give preference to one of the aunts of his king. This project is worthy of the highest praise. By allying himself with the royal family, he wanted to give himself a defender, and conform to the decrees of the assembly, which says in its declaration of the rights of man: All men are equal in rights. According to this principle, M. Desmoulins believed as much as anyone else that he had rights over Madame Adélaïde, and he sought to assert them.

The journal Chronique du Manège mocking Camille in an article titled Faits et Gestes de Sieur Camille Desmoulins (1791)

Yet I am still writing, someone will tell me. Yes, but I learn that on Tuesday evening, until midnight, four assassins were waiting for me, Danton and the Orator of the People (Fréron); the next day at the Palais-Royal, for having replied to people who had provoked me with insulting words, that I returned his contempt to Lafayette, I saw myself surrounded by aposted rascals who showed me their fists in the midst of patriots in silence, and awaited only the slightest defensive movement on my part to reply with daggers to my accusations against Lafayette. On Easter day in the middle of noon, aide-de-camp Parisot had knocked out Carra, in the presence of a patrol of 12 grenadiers from his section who did not say a word. […] On the evening of the 18th, in an infinitely large crowd of snitches and satellites of Mottier, a motion was made to hang us, Audouin, Fréron, Marat, Prudhomme, me, and all the writers who did not bend the knee before the idol.

Camille in number 75 of Révolutions de France et de Brabant (May 2 1791)

I left the de Vaufleury's literature cabinet with my veni mecum, that is to say, with a sturdy cane and pistols, as inseparable from the journalist as the king is from the National Assembly, and which are our veto. The same bookstore clerk who told me fifteen days ago that M. Lafayette despises me too much to try to assassinate me, dissatisfied with the account I had given of the conversation in my number 74, followed me with the number in his hand, and, pointing to the article, asked me if I recognized it. I replied that there was the law and the courts, if he thought he had cause to complain. Then the fellow gave me the customary compliments of these gentlemen in such a meeting, that I was a rascal, etc. etc that he would like to meet me in a suitable place, that he would do his best to cut my throat; that if we were only outside the Palais-Royal, he would knock me out, that he feared neither my pistols nor my cane; and to prove it to me, he finished his harangue by hitting me in the face with the number as hard as he could. I had endured insults as did Pericles, Cicero, and many other great personages who were well worth me, and who were not lacking in heart, as they showed in stronger circumstances; but feeling myself colaphised with my works, I could not stand it; I remembered the beautiful exclamation of Demosthenes, apropos of the slap given to him by Midas, being slapped on the cheek, slapped in a public place, slapped in the presence of the Athenians who had honored him with their suffrages, etc. I looked with pity, not on this Midas, but on the Midas in front of me, who only had my number in his hand, and I admired his audacity to hit me with a patriotic paper, in the same place where I had first called to arms, where I had first taken the cockade. I could, I told him, blow your brains out, but at the same time I thought that, thanks to the revolution, a citizen was no longer obliged to go and get himself killed at Kevrein, by the first rascal who had insulted him. I reflected that a blow with the cane would suffice to repair the injury, and as a form of retaliation, I applied weight and measure to his shoulders. My assailant went back to insult and provoke me. I answered that I was not unaware that for the past two years, I have been crossing a forest where I am exposed; that consequently I was always provided with the precautions which a traveler should take against assassins; but that I did not accept their appointment.

Camille in number 77 (May 16 1791) of Révolutions de France et de Brabant

What a terrible quarrel I had the other day with Jean-Paul Marat about a misprint, having written l’apostat in place of l’apostolate! In spite of these disagreements, to which an incorrect impression exposes me, seeing a wife as interesting as mine be the butt of the most atrocious defamation for having attached herself to my fate; to the extent she cannot go for a walk in public with her mother without being told: what a pity that this pretty woman belongs to a hanged man?

Camille in number 78 (May 23) of Révolutions de France et de Brabant

So Desmoulins sure had enemies (I mean, you could basically say that about anyone who has ever chosen to make his political opinions known to the public, now as then). However, it’s hard for me to get an impression regarding if he was more hated (or loved for that matter) than any other successful journalist of the time, conservative or radical alike.

The second of Camille’s papers, La Tribune des Patriotes, was co-founded with his friend and fellow journalist Stanislas Fréron. However, it only ran for a month before it had to shut down, making it hard to say if it gathered any particular enemy. The same thing goes for the fourth paper Révolutions de France et de Brabant: second partie that ran for only two months and is so unknown it hasn’t even been digitalised yet.

For the fourth and final paper, Le Vieux Cordelier, you’re right in that it ended up making Camille unpopular with the Committee of Public Safety. However, what is often not underlined as much is that he started the journal very much in support of the committee (I mean, he even got Robespierre — more or less the figurehead of it — to proofread his first two numbers before sending them to the printer). If he in later numbers would deplore of some of the things currently going on and bring forward new ideas, his goal was never to overthrow the committee or even change its direction in a particulary radical way.

A bigger enemy was Jacques René Hébert, and it was to conbat him and his ”ultra-revolutionaries” that Desmoulins started the journal and Robespierre helped him with the first issues. After it got going, Hébert denounced Desmoulins three times at the Convention and/or Jacobins (December 21, 31 and January 5), three times in his journal Père Dushesne (number 328, 330, 332) and even in an entire pampleth — J. R Hébert, auteur du Père Duchesne, à Camille Desmoulins et compagnie, always with some variation of Camille being a moderate who was after him. That’s way more than the total of four times Camille was denounced by a CPS member due to his journal (Collot d’Herbois on December 23and January 5, Barère on December 26 and Robespierre on January 7) and in all those cases, the speaker was still trying to see in him a man of good faith. Hébert was not the only person to hold these opinions regarding Camille, but he was the most outspoken. Camille was not late to answer his attack and the Vieux Cordelier and the Père Dushesne were often compared and pinned against each other during the short lifespan of the former. In that way Hébert might be the closest Camille had to a ”nemesis” if I may use such a silly term — which it’s why it’s so ironic that they were both executed within less than a two week gap anyway, while their widows became friends while in prison and the last thing they did before being executed was hug each other.

I don’t know if I would say Hébert was responsible for Desmoulins’ demise, but I suppose the increasing bickering between the two contributed to the CPS decision to just eliminate both of them.

#camille desmoulins#desmoulins#hébert#i wish camille being slapped in the face with a paper was a more famous image…#ask

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

History 101: The Jacobin Club

The Jacobin Club, officially known as the Society of the Friends of the Constitution, originated in 1789 in Versailles. Soon after its establishment, it moved to Paris. Its name "Jacobin" was derived from the Jacobin convent in Paris, where the group held their meetings. Comprising mainly members from the middle class, the Jacobins were not restricted to any specific socio-economic class. As their influence grew, they established affiliated clubs throughout France, highlighting their widespread reach.

Jacobins were dedicated republicans who ardently believed in ending the monarchy. Their political ideology was deeply rooted in the Enlightenment principles, particularly the ideals of liberty, equality, and fraternity. They leaned towards the establishment of a centralized republic as opposed to a federal system. This perspective made them unique in the context of the diverse political environment of the French Revolution.

However, the Jacobins are most infamously recognized for their role in the radical phase of the French Revolution, which precipitated the Reign of Terror from 1793 to 1794. Under prominent leaders like Maximilien Robespierre, Louis Antoine de Saint-Just, and Georges Couthon, the Jacobin-dominated Committee of Public Safety took the reins of the revolutionary government. This period saw the execution of many, perceived as enemies of the revolution, including the likes of King Louis XVI and Queen Marie Antoinette.

But their radical stance became their undoing. The Reign of Terror and the Jacobins' uncompromising methods led to divisions even within their ranks and diminished their public support. Robespierre's growing distrust and the rampant executions, including those of fellow Jacobins, led to widespread disillusionment. His eventual arrest and execution in 1794 marked not only the end of the Reign of Terror but also the decline of Jacobin power. The subsequent period, known as the Thermidorian Reaction, was marked by a backlash against the Jacobins, leading to the execution or imprisonment of many of their leaders and the closure of their clubs.

In the annals of history, the Jacobins have left a profound legacy. While their methods, especially during the Reign of Terror, remain a topic of debate, their unwavering commitment to a unified and centralized French Republic laid foundational stones for subsequent French governments. The term "Jacobin" has transcended its historical context and is now used globally, often to denote radical left-wing revolutionaries or those perceived as excessively radical.

0 notes

Text

it was and is an option, very tempting an option, to prioritise an ideology over the livelihood of self and kin.

never the most popular decision, but by no means a rare one.

antoinette implicitly signed up for exactly that when she looked to find a hiding place for her children AND to use a foreign army against her people. her reliance on what was to her the status quo was as extreme a decision as, say, marat's decision to renounce lafayette, bailly, mirabeau, and necker, and later brissot and the brissotins, making so many powerful enemies who could, and did, go as far as restricting the publishing of his newspaper, attempting to arrest him, and attempting to establish his guiltiness in court.

we could talk about the difference between being "extreme" (i.e. requiring unusual and swift action) and being "extremist" (i.e. knowingly undermining the safety of the community). but this article here can do a better job than i can, and it's free, so give it a read.

if we refer to the (wrong) logic of patriarchy, then since women quite often were required to change their identities so as to align with that of their husbands, antoinette certainly was someone who held power over, and had duty towards, the safety of the french in their entirety. the safety of the austrians were not supposed to be a priority for her.

and so with her betrayal came the risk of herself being killed, either executed or assassinated, or many other forms of being ended, politically or physically, all of which would leave her children parentless, looked after by less suitable guardians, that is, if they could find new guardians at all.

causes that could affect entire countries did, and do, require that level of commitment.

the same level of commitment, though for very different causes, were taken up by michel lepeletier, by jean-paul marat, by robespierre the elder, robespierre the younger, le bas, saint-just, couthon, and hanriot, by romme, duquesnoy, and goujon.

re: "a path to a republic turning bloody", we need to examine the question "how much revolutionary violence is too much" -- not to attempt to answer it, but to examine it.

Žižek's point would be to refrain from drawing such a "too much" line at all, since

... every violence of the oppressed against the ruling class and its state is ultimately 'defensive'. If we do not concede this point, we volens nolens 'normalize' the state and accept that its violence is merely a matter of contingent excesses (to be dealt with through democratic reforms). This is why the standard liberal motto apropos of violence -- it is sometimes necessary to resort to it, but it is never legitimate -- is inadequate. From the radical emancipatory perspective, one should turn this motto around. For the oppressed, violence is always legitimate (since their very status is the result of the violence they are exposed to), but never necessary (it is always a matter of strategic consideration to use violence against the enemy or not).

(foreword to Sophie Wahnich, In Defense of the Terror: Liberty or Death in the French Revolution)

it is well and good to say "this statement of 'a path to a republic always seems to turn bloody' is oversimplification", but i wish to go further. we only decry as bloody the violence that we wish were we cannot justify, that we wish to prevent others from justifying. we too often see violence as a means to some end, when violence done right (and what that looks like is a question that can be used to separate believers of different ideologies) often is the end and not the means.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Committee of Public Safety

The Committee of Public Safety was a powerful political body during the French Revolution. It was established on April 6, 1793, by the National Convention, the revolutionary government of France at the time. The primary purpose of the Committee was to deal with internal and external threats to the revolution and to protect the Republic.

Initially, the Committee consisted of nine members, but later its size was expanded. The most well-known and influential figure associated with the Committee of Public Safety was Maximilien Robespierre, who became its prominent leader. Robespierre and his fellow members were often referred to as "Montagnards" or "Jacobins" because they were part of the radical political faction within the Convention.

During its tenure, the Committee wielded immense power and was granted extraordinary authority to address the many challenges facing France, including military threats, internal rebellion, food shortages, and counter-revolutionary activities. It took a proactive and often ruthless approach in suppressing opposition and implementing policies to protect the Revolution. The Committee was known for its use of revolutionary tribunals, which conducted trials and executed perceived enemies of the Republic, including those associated with the monarchy and aristocracy.

The Reign of Terror was a particularly infamous phase associated with the Committee of Public Safety, marked by widespread political persecution and mass executions of alleged counter-revolutionaries. This period lasted from late 1793 to mid-1794 and was characterized by a climate of fear and suspicion.

The Committee's power began to wane after Robespierre's fall from grace and execution on July 28, 1794. Following this event, the Committee was restructured, and its authority was diminished as the revolutionary fervor subsided. The Thermidorian Reaction, named after the month of Thermidor in the French Republican calendar, led to a more moderate government and the end of the Reign of Terror.

In summary, the Committee of Public Safety played a crucial role during the French Revolution, exercising vast authority to protect the Republic but also becoming infamous for its radical and often oppressive actions.

#CommitteeOfPublicSafety#FrenchRevolution#NationalConvention#MaximilienRobespierre#ReignOfTerror#Montagnards#Jacobins#RadicalPolitics#RevolutionaryGovernment#ThermidorianReaction#History#PoliticalPower#HistoricalFacts#RevolutionaryFrance#RevolutionaryCommittee#today on tumblr

0 notes