#tommy orange

Text

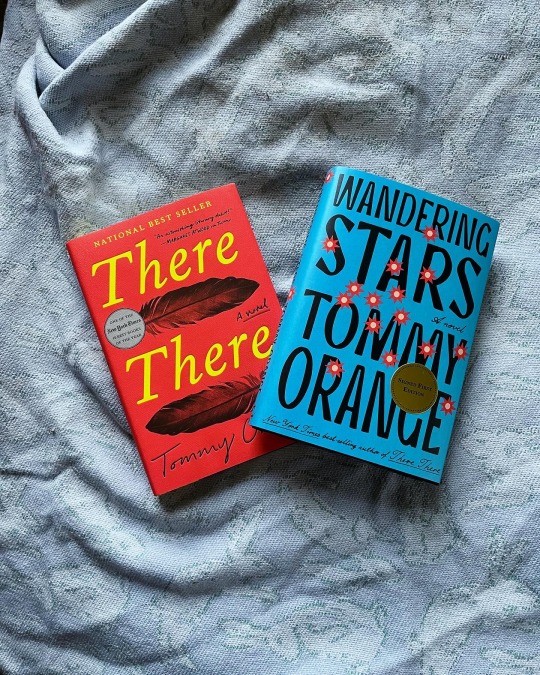

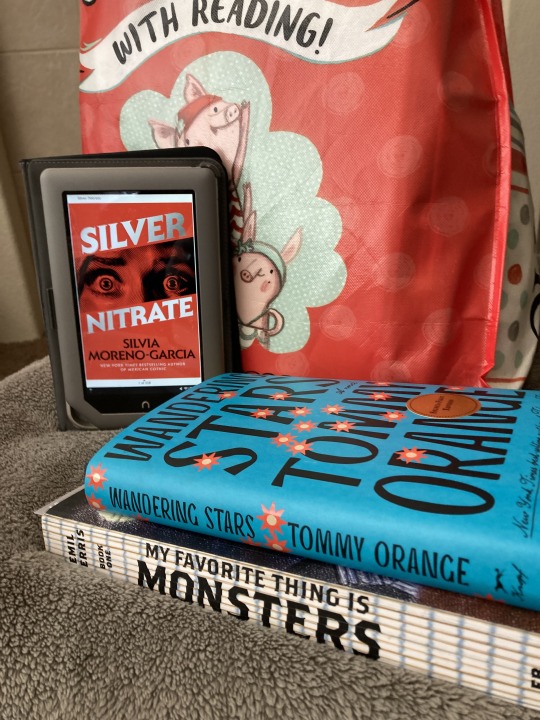

I can’t wait to read these 😍

#godzilla reads#tommy orange#there there#wandering stars#books#book blog#reading#bookworm#tbr#bookish#booklover

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

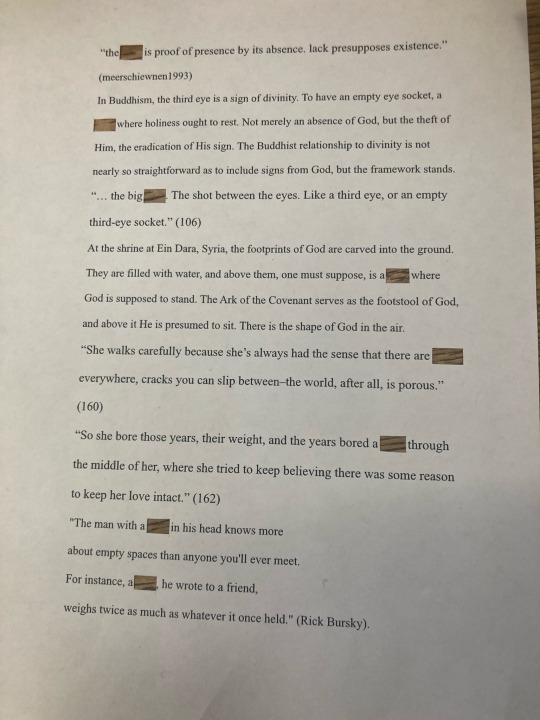

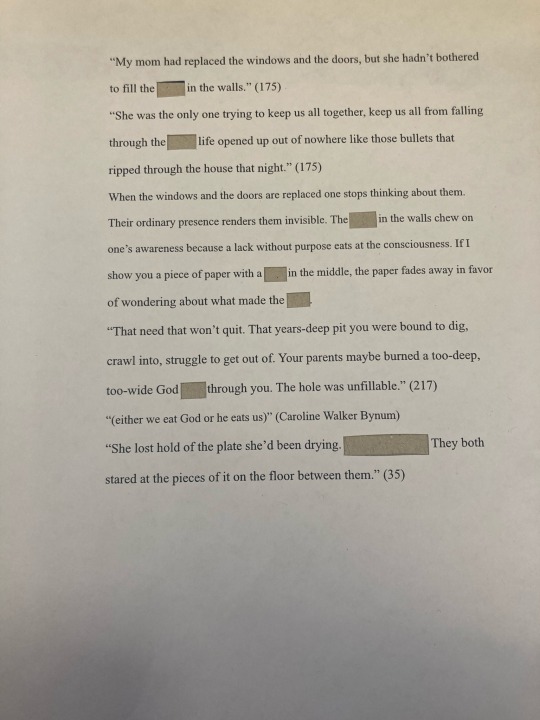

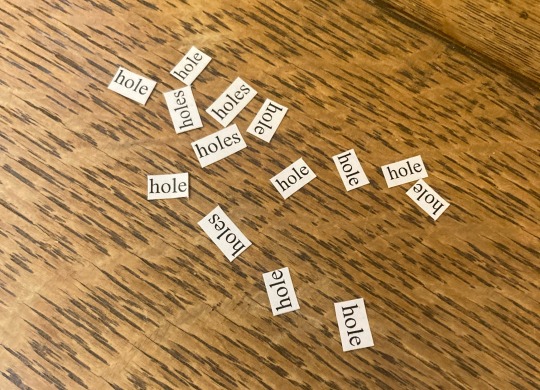

school project on hole theory + tommy orange’s there there

plus

124 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Later you remember your mom saying to take drugs was like sneaking into the kingdom of heaven under the gates. It seemed to you more like the kingdom of hell, but maybe the kingdom is bigger and more terrifying than we could ever know. Maybe we've all been speaking the broken tongue of angels and demons too long to know that that's what we are, who we are, what we're speaking."

Tommy Orange, There There

#quotes#literature#lit#poetry#spilled ink#american literature#modern literature#native american literature#indigenous literature#tommy orange#substance abuse#drug use#religion#indigenous writers#native american writers#indigenous authors#native american authors

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

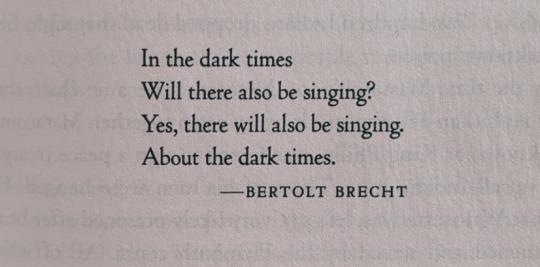

#my upload#bertolt brecht#there there#tommy orange#dark academia#light academia#classic academia#poetry#userliterature#romantic academia

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wandering Stars: A Novel

By Tommy Orange.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

"It's just as important for you to hear yourself speak your stories as it is for others to hear you speak them."

- Tommy Orange

"If you love a book, talk about it! If you love a story, let other people know!"

- Rick Ouimet

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kids are jumping out the windows of burning buildings, falling to their deaths. And we think the problem is that they’re jumping.

There, There by Tommy Orange

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cannot recommend this book enough, specially if you have ancestors of indigenous blood. The book is about the lived experience of several indigenous characters of different ages and life experiences living in modern day Oakland, all converging on a powwow. It offers such a raw and real perspective on what it means to be native in a land and society that has not made space for you. There is a quote in the prologue that has stayed with me:

Being Indian has never been about returning to the land. The land is everywhere or nowhere.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

“How can I not know today your face tomorrow, the face that is there already or is being forged beneath the face you show me or beneath the mask you are wearing, and which you will only show me when I am least expecting it?”

—Javier Marías (Tommy Orange, There There)

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Books in 2020

Since this year is preserved in amber, I’ve done a much better job remembering the books I read as compared to 2019. Only six books have turned to dust in my mind.¹ On the other hand, I only read about two-thirds as many books as usual. It’s a minor example of the way the pandemic crabbed everyone’s life in 2020, but it can be added to the quilt.

Almost everything we did that year was dictated by the practicalities the pandemic forced on us. In a dull way, that “looking inward” we all had so much time to do strongly shaped this list, particularly the middle of it: when I needed something to read, I could only look inside my apartment.

Fates and Furies, Lauren Groff (Jan. 2-17)

Lots of acclaim for this book. All of it misplaced. The main problem is that the novel concerns (in part) one character’s brilliantly written plays. But on the basis of the material we see, the plays are pretty weak, so the credibility of the larger story is shot. I suppose the character’s work is as good as the writing in this novel itself, which I also thought little of. Tediously dour (it takes place in a world where, apparently, nobody has ever laughed or been laughed at) and full of sentences that sound clever, but don’t actually mean anything (to paraphrase a movie). Barack Obama said it was his most enjoyed book of 2015, which I have to hope was just the stress of the job getting to him.

Sabrina, Nick Drnaso (Jan. 2-5)

Timeliness is not something that I usually value, but Sabrina makes it seem like a worthy pursuit. It’s about crime and the ugliness of the internet and “fake news,” so it’s sure to grab any contemporary reader’s attention. But the craftsmanship of the art and the intelligence in the writing are so good that this would be an interesting book, even if we lived in Universe B, where those issues aren’t so omnipresent.

Qualification, David Heatley (Jan. 18-23)

I once read Heatley slagging off Monty Python and the Holy Grail on the grounds of it not being wholesome enough. So I shunned him for ten years, until this book popped up at the library. It’s about the numerous 12-step programs Heatley participated in and essentially became addicted to. That irony is sort of analyzed, but not deeply enough to feel that it’s really been addressed. Still, his honesty, the details of how the programs work, and the depictions of the people he meets there are good enough.

The Child in Time, Ian McEwan (Jan. 21-31)

The set-up is a nightmare, one of the scariest things I can imagine – a child is kidnapped and never found – but most of the book deals instead with the aftermath, years later, as the father tries to reintegrate into a world that’s moved on from his horror. The relationship between the main character and his estranged wife is good, and though some of the other threads (political, ghostly) didn’t stick with me so much, the well-captured emotions of the characters alone make this worth a read. I’m only now realizing, with surprise, that I haven’t picked up any of McEwan’s other books since this.

Other People, Joff Winterhart (Jan. 23-27)

Two stories, one about a son and a mother, the other about a son and a father figure. Both a little sad, both a little sweet. The older folks are a bit buffoonish, but turn out to be subtly good influences on the teenagers. I liked that the stories were about young people and drawn in a style that looked like something a high schooler (a talented high schooler!) would have drawn in his or her notebook.

Peepshow, Joe Matt (Jan. 8 - Feb. 1)

Not sure if I remember this one, or if I’m just remembering other Joe Matt comics I’ve seen throughout the years. But either way, I can confidently say that it’s full of frank presentations of Matt’s life and relationships, with no censorship of his most depraved thoughts and behaviors. It’s the sort of thing that could seem false and self-aggrandizing (“I fear not the audience’s gaze, ecce homo, etc, etc”), but in Matt’s case, it never comes off that way. He’s just telling the story as it comes naturally to him, and if you can tolerate his excesses, it’s enjoyable.

Magic Mirrors, John Bellairs (Feb. 1-11)

I have read and re-read all of John Bellairs’ young adult novels, but I had never before attempted his adult work, all of which is anthologized in this book. The Pedant and the Shuffly and St. Fidgita and Other Parodies are forgettable, but The Face in the Frost and its incomplete sequel, The Dolphin Cross, are great fun. They’re both about Prospero, a wizard who does very little magic, and mostly wanders around from one odd, irreverent chapter to another. I most enjoyed the town that disintegrates as Prospero tries to flee, and the dinner scene with the tank of sentient fish.

Into the War, Italo Calvino (Feb. 13-19)

No fantasy, no whimsy, no invention. This is a most un-Calvino-like collection of three short, probably autobiographical stories about being a teenager at the onset of World War II. It’s never terribly interesting, and you start to sense that Calvino felt obligated to write this, as though he wasn’t sure if he was allowed to put his talents to use on off-the-wall novels rather than sober stories of important (“important”) realism (“realism”). What does work, though, is his rendering of teenage life, which seems to be consistent across time and place.

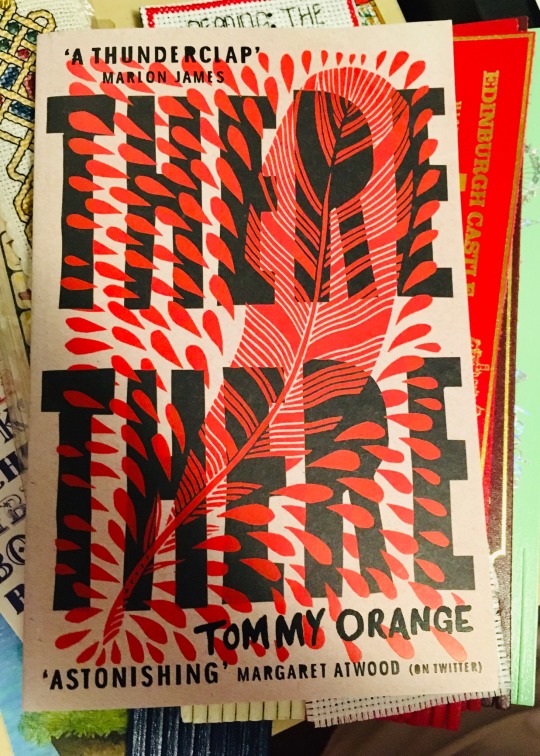

There There, Tommy Orange (Feb. 19-27)

It’s very good. Chapters jump between the stories of a dozen Native Americans in the Oakland area, all of which eventually coalesce gracefully and unpredictably. There’s a lot of nicely rendered detail and effortless intelligence in the characters and the plotting, and there’s the charge that you get from realizing, as you read their stories, how infrequently these stories are told.

Once I Was Cool, Megan Stielstra (Feb. 28 - Mar. 5)

A collection of essays about being young, about being a thirtysomething, and about being a thirtysomething who’s reminiscing about being young. It’s all fine and Stielstra never once lapses into the sort of loathsome snobbery that you sometimes see in essay collections like this. But none of the material ever achieves escape velocity; it’s always mildly interesting and mildly amusing. There may be some loathsome snobbery at work in me, though: having lived so long in New York, I reflexively view Stielstra's Chicago-based anecdotes as inherently trifling.

L.A. Woman, Eve Babitz (Mar. 6-11)

I don’t think I was at all aware of Babitz’s celebrity when I picked up this book, but even I could tell that it was a memoir disguised as a novel. That works okay – the vision of Los Angeles that she presents (appalling and vicious, yet you wouldn’t want to be left out of it) is powerful in any format – but the book might have been stronger without the vague gestures towards a novelistic structure. Of course, my appraisal came from a distracted mind: this is the book I was reading when the world started to fall apart.

Thieves Fall Out, Cameron Kay (Mar. 13-24)

Written pseudonymously by Gore Vidal for some quick cash. He hoped it would be forgotten, and it was only after his death that it was republished. Vidal was perhaps overly dismissive of the book, but nothing of value would have been lost if the publisher had respected his wishes. The Egyptian setting is decently evoked, and the twists and turns of the pulpy plot are serviceable, but the whole thing is impersonal – surprising for a writer who usually had no trouble putting his voice to work.

The Gigantic Beard That Was Evil, Stephen Collins (Mar. 16-18)

A cute little fairy tale about a neat, orderly island that is disrupted by one man’s beard, which grows and grows until it overwhelms everyone’s existence. It could probably be read successfully as a cheeky story about conformity, but I hope there wasn’t anything that prosaic or moralistic behind it. I like it more as a loony story with no point. The art style reminds me of the end credits of the 2004 film adaptation of A Series of Unfortunate Events (which is a compliment, as the credits sequence was the best part of the movie). After I checked out this and the Vidal book, the Los Angeles libraries shut down, even to returns, so these two sat on my table for months.

4 3 2 1, Paul Auster (Mar. 25 - Apr. 18)

Stuck at home, I started reading books that I’d had on the shelf for years, books too heavy to have read during my commute. This one introduced me to the new experience of being disappointed by Paul Auster. It’s not as dazzling as his other books, which usually pack so much invention into a brisk story. Other than the premise (four divergent versions of the same man’s life told concurrently), this one is pretty conventional. And there’s a lot of seen-it-before reminiscences about the America the Boomers grew up in, and the upheavals of the 1960s. Boring material in anyone’s hands. Still, page by page, the writing was good enough. The nested story that his hero writes about the inner life of a pair of shoes was terrific.

Ulysses, James Joyce (Apr. 19 - May 1)

I did read every single word of this, but very little of it stuck with me. Aside from the lines that seemed to cater to me specifically – nostalgia-inducing descriptions of Dublin streets; a gorgonzola sandwich; and an early scene of Bloom talking to his cat (who says, “Mrkgnao!”) – I didn’t understand what I was reading. This is probably due to me not being smart enough, but how about this: Samuel Beckett said that James Joyce “had gone as far as one could in the direction of knowing more…I realized that my own way was impoverishment, in lack of knowledge and in taking away, subtracting rather than adding.” So maybe some of us are wired to receive Joyce, and some of us are wired to receive Beckett.

The Complete Eightball, Daniel Clowes (May 2 - June 7)

I had read most of these stories in reprints and anthologies, but this collection has them as they originally appeared in Clowes’ comic books. This is the best way to read them. A chronological arrangement means you can see the evolution of his talents. Plus, you get the original covers, as well as all the sundry material that filled up the pages between stories, like advertisements, editor’s notes, and letters from readers who accuse him of selling out by moving from Chicago to Oakland. I particularly liked when Clowes encouraged his readers to record their crank calls (“long denied [their] rightful place as one of the great, indigenous American artforms”) and send the tapes to him for evaluation and prizes. The contest is “quite legit, I assure you.”

The End, Karl Ove Knausgaard (May 2-20)

The last of his six-volume autobiography cycle, but the first one I read. The ordinary details of his life are reported nicely, without ornamentation, and the meta-material, as he deals with the fallout from having used his friends and family as grist in the earlier volumes, is candid and reflective. There’s a long and slightly baffling section in the middle where he discusses Hitler’s autobiography, but it makes you feel appreciative: Knausgaard read it so you will never have to.

United States, Gore Vidal (May 21 – June 19)

The best of Vidal. 40 years of essays in one 1,700-page book with miniscule type. There are, of course, lots of good zingers and well-aged material about drug laws, police brutality, and the corruption of the political process. But with such a quantity of work, you get to spot some of his usually deemphasized sweetness. There are warm remembrances of Tennessee Williams and Eleanor Roosevelt and the Wizard of Oz books.

Flappers and Philosophers and Tales of the Jazz Age, F. Scott Fitzgerald (June 20-30)

19 stories across two collections. Fitzgerald apparently referred to about half of them as “trash,” but I liked them. There’s a good balance of humor and happy endings with some unexpectedly gothic material. “The Diamond as Big as the Ritz,” a gruesome tale about greed and the terrors of rural America, is a standout, and “The Curious Case of Benjamin Button” would be too, if we weren’t already so familiar with the premise.

The Coast of Utopia, Tom Stoppard (July 11-17)

I had this trilogy of plays on my shelf for ten years, carried it between five homes, waiting for the right time to read them, hoping that I would have the opportunity to see them performed first. I should have kept waiting. The scripts are impenetrable, owing mostly to there being several dozen characters (with long Russian names) to keep track of.

Homegoing, Yaa Gyasi (July 20-25)

The first book in four months that I was able to check out of the library. I had to pick it up in a sanitized paper bag from a branch miles from my home. It was worth the trip. The novel follows two branches of a family down through several generations. One stays in Ghana, the other is taken to America. Each chapter follows a new descendant in the family line, and each time a chapter ended, I was sad to be leaving behind that character and that setting. But every subsequent chapter was just as good, so I was happily swept through to the end.

All Trivia, Logan Pearsall Smith (July 26-30)

It was well reviewed in the Gore Vidal collection. A couple hundred short aphorisms and observations on all manner of things, both physical and abstract. Pretty good, and I remember reading a few of the best ones aloud to people in earshot, but they’ve all disappeared now. There was something funny about sunspots…

Another Day in the Death of America: A Chronicle of Ten Short Lives, Gary Younge (Aug. 3-8)

Younge picks a 24-hour period and tells the stories of 10 American children (aged nine to 19) who died by gun violence in that time. It’s a really expert example of journalism. Younge renders the victims, the killers, the survivors and the deaths themselves vividly without ever become maudlin or trashy. Nor is he heavy-handed. This isn’t a gun control advocacy tract (though it works very well as that); it’s just a description of ten deaths that would otherwise have not been known to the wider public, and an invitation to think about how you feel to be living in a society where this happens every day.

The Groves of Academe, Mary McCarthy (Aug. 8-13)

After my success with McCarthy in 2019, we slid right back into the mud on this one. It’s a satire about universities, with one professor out for revenge after his teaching assignment is rescinded. I usually flip for novels like this, or at least I used to, but this one never grabbed me. And yet, I still keep checking the “McC” shelf at the library…

Why Time Flies: A Mostly Scientific Investigation, Alan Burdick (Aug. 13-17)

Pop science about time and how we perceive it. Pretty good, and has some fun little facts to deploy in party conversations (“Want to know what happens when a person lives in a cave for two months without sunlight or clocks to tell time?”), but at length it wasn’t as interesting as the excerpts in the New Yorker review that made me want to check it out in the first place.

Who the Hell’s in It: Portraits and Conversations, Peter Bogdanovich (Aug. 17-27)

A good collection of profiles and critical appraisals of actors and directors. Bogdonavich doesn’t bring out the knives. He seems to like everyone, or at least have a fondness for everyone he talks to or about. He even likes Jerry Lewis, which is hard to understand, based on the person that Lewis reveals himself to be in their long interview: vain, angry, and constantly bestowing his “generosity” on those less talented than him. I’m not sure it could have been more damning if it had been writing by a person who hated Jerry Lewis.

Moby-Dick, Herman Melville (Sep. 4-16)

This one works. It lives up to the hype. Much livelier and more readable than you would believe. It’s diverse in its approach, taking the whale narratively, biologically, symbolically, historically…any way you want to look at a whale, it’s here. And each chapter is so short that even if you come upon a dull one, you can just gloss through it and quickly be on to something new. Captain Ahab deserves his reputation as an eternal character. My favorite scene is the one where the ship encounters another captain injured by Moby Dick, and Ahab becomes infuriated that this other man has managed to laugh about it and move on with his life.

Quick Service, P.G. Wodehouse (Sep. 27-30)

Everything Wodehouse writes is brilliant to some degree and forgettable to some degree – forgettable because all of his stories are so similar as to run together in your memory. (This is not a strike against him; the familiarity is what gives him space to run wild with set pieces and verbal invention.) This novel has a higher than average degree of forgettability, owing to less than average characters and scenarios. Still, reading anything by Wodehouse will only make you healthier.

The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Cartoonist, Adrian Tomine (Sep. 30 – Oct. 2)

Simple vignettes of incidents in Tomine’s life that shaped him as a cartoonist. By a freak chance, these are totally congruent with extremely humiliating moments in his life. The only complaint I have is that it was too short.

Cosmicomics, Italo Calvino (Oct. 1-5)

If Into the War was an un-Calvino-like book, this one is Calvino-ish to a fault (if it’s possible to find fault in him). These 12 stories are about outer space and ancient life: the last dinosaur, the first creatures to walk on land, a time when the moon was close enough to the earth that people could hop between them. I was about to say that this was maybe shaky ground on which to build, that Calvino is better when he begins in our familiar Earth and then gets fanciful…but even writing that list of topics made me smile. And then there’s the best story, where the narrator, searching the skies, sees a galaxy with a sign reading, “I saw you,” and realizes that he was spotted, one hundred million years before, doing something embarrassing! Forget what I started to say. This book is great.

Picturing Will, Ann Beattie (Oct. 7-12)

Will is a little kid, surrounded by struggling adults. There’s not much of a plot, just images from the life of a small family. Like everything Beattie writes, the story is fragile and slow and devastating, and she fills her characters with a lot of psychological depth. I have to dock it points, however, for the introduction and mishandling of a particular plot point that I won’t spoil. I’m not sure you can casually bring something so fraught on board without it capsizing the whole book.

’Tis, Frank McCourt (Oct. 14-21)

The sequel to Angela’s Ashes, following McCourt as he tries to make it as a young man in America. Even away from horrible Irish poverty, his life is still pretty bleak. McCourt takes a lot of abuse from all sorts of people, and even once he’s settled down with a teaching career and a family, the hits keep coming. And that’s not to mention the horrendous health problems (endless eye infections!) that plague him for the first few years. But, “stories only happen to those who are able to tell them,” and McCourt relays everything with a lot of humor and sincerity and poetry.

Nineteen Stories, Graham Greene (Oct. 22-31)

The short story isn’t his medium. All 19 of them are fine, but only two are memorable: The End of the Party” about a child’s game of hide-and-seek that ends tragically, and “The Basement Room,” about a young boy disappointing and being disappointed by his hero. Interesting that an author famous for writing about grown-up matters like politics, espionage and war should write so well and so evocatively about the experiences of children. (Wait, no, that isn’t interesting.)

Hate Inc., Matt Taibbi (Oct. 31 – Nov. 7)

In his introduction to this book about the deterioration of the media, Matt Taibbi offers himself as an example of how nastiness has been incentivized, recounting that he once won the National Magazine Award for an article referring to Mike Huckabee as a “nut job” who resembled an “oversized Muppet.” I don’t think he needs to apologize for that (and amusingly, later in this book, he reflexively lets fly some even more juvenile insults without realizing he’s fallen back on his old tricks), but it’s a fair starting point for his dissection. Nothing in this book is a surprise – yes, the political media, particularly cable news, profits from keeping its audience in a state of constant agitation – but the examples he marshals are good, and his style is clean and straightforward.

Roads, Larry McMurtry (Nov. 24-27)

McMurtry’s memoir of driving across the country. It’s unusually decentered for a journey immortalized in a book: he’s not driving for more than a few days per month, he’s not taking scenic routes (he sticks to the biggest interstates), he’s skipping big portions of the highways he does take, and he doesn’t spend too much time talking about his destinations. He calls the book Roads, and he means it. But he makes it work. His thoughts and observations, whether of the landscape surrounding him or merely inspired by it, are aimless, but smart and confident. Though my attitude towards cars is less fond than his (it’s been rudely called “ecoterroristic”), McMurtry evokes a convincingly romantic view of American driving.

Misery, Stephen King (Nov. 27 - Dec. 2)

Highly acclaimed and deservedly so. The claustrophobic set-up never gets old. The violence, though shocking and extreme, never become tasteless or silly, as in a few of King’s stories I could mention. And the villain, Annie Wilkes, steals the show. It’s quite scary to have the dawning realization that she’s sane enough to successfully pull off her hideous plan, but too crazy to be reasoned with, or even predictably strategized against. It’s perhaps an unrealistic balance, but in Misery, I believed it unreservedly.

***

There are two ways to look at it. It was a successful year: I only read one out-and-out stinker. At the same time, it’s a highly conservative list. Not to put down any of these authors individually, but I feel a little embarrassed by the cumulative effect of all of these familiar names. I can stick most of the blame on having been unable to wander the library and browse, but it could also be an incipient impatience. I’m getting older. Maybe I just don’t feel like taking my chances with some new author.

Or maybe this is just one of those bad habits that we get to leave behind in 2020, chalking it up to the pressures of facing that endlessly rising tide of shit, rather than any personal failings. That’s the fun (or the “fun”) of having survived a pandemic. You get to look back at your life and figure out, “Was that me? Or was it the virus?”

¹Heads or Tails, Lilli Carré; Old Souls, Brian McDonald & Les McClaine; Alex, Mark Kalesniko; The Hard Tomorrow, Eleanor Davis; Cannonball, Kelsey Wroten; and The Collected Stories of Mavis Gallant

#lauren groff#nick drnaso#david heatley#ian mcewan#joff winterheart#joe matt#john bellairs#italo calvino#tommy orange#megan stielstra#eve babitz#cameron kay#stephen collins#paul auster#james joyce#daniel clowes#karl ove knausgaard#gore vidal#f scott fitzgerald#tom stoppard#yaa gyasi#logan pearsall smith#gary younge#mary mccarthy#alan burdick#peter bogdanovich#herman melville#pg wodehouse#adrian tomine#ann beattie

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

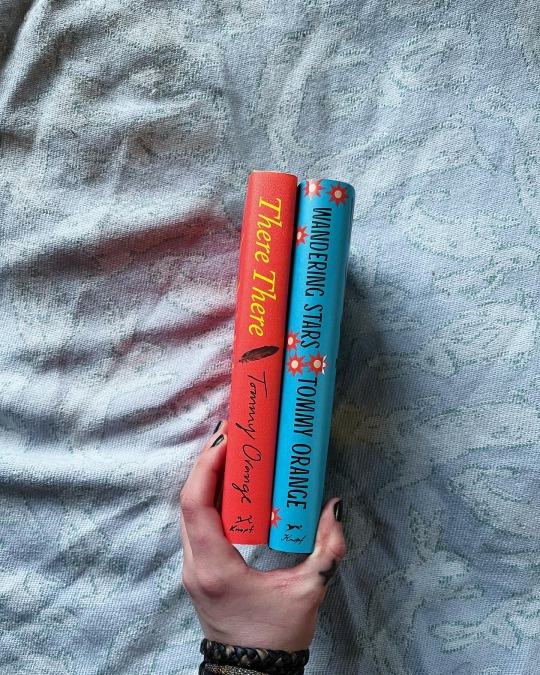

01.05.2022

First book of the month - and it is for uni, of course! I'm holding a presentation on this book, so I'll have to annotate and so forth

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

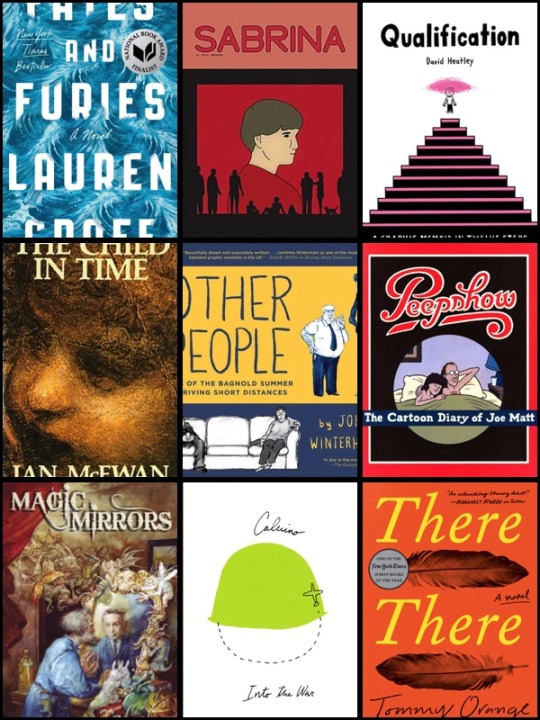

JOMP Book Photo Challenge - March 1 - TBR This Month

My To-Read pile for March (maybe)

1 note

·

View note

Text

Review: "There There" by Tommy Orange -

An extraordinary first work by Orange who fortunately has more novels ahead. Here his complex characters and social commentary are spot on, thwarted a bit by Orange's not trusting them to complete their stories on their own.

youtube

#bookworm#literature#book reviews#read read read#books#tommy orange#there there#native american literature#indigenous americans#Youtube

0 notes

Quote

But nothing is original. Everything comes from something that came before, which was once nothing. Everything is new and doomed.

There, There by Tommy Orange

15 notes

·

View notes