#united nations climate conference

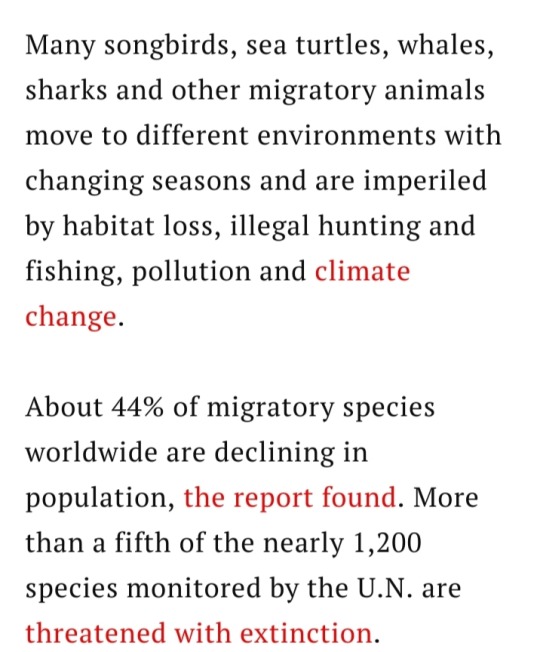

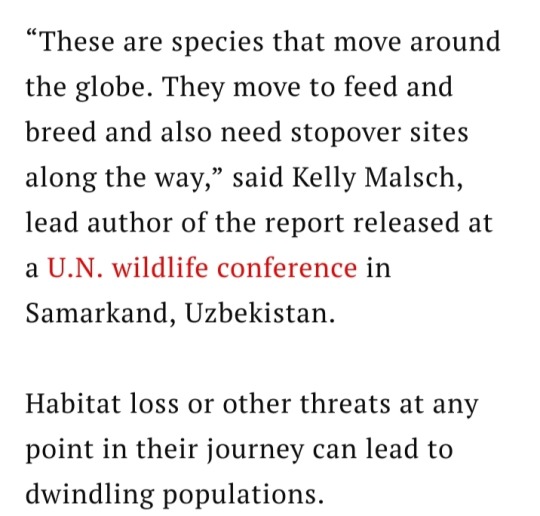

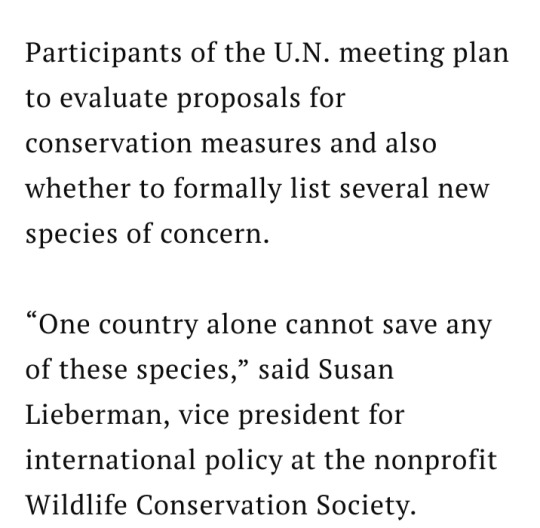

Text

The world isn’t on track to meet its climate goals — and it’s the public’s fault, a leading oil company CEO told journalists.

Exxon Mobil Corp. CEO Darren Woods told editors from Fortune that the world has “waited too long” to begin investing in a broader suite of technologies to slow planetary heating.

That heating is largely caused by the burning of fossil fuels, and much of the current impacts of that combustion — rising temperatures, extreme weather — were predicted by Exxon scientists almost half a century ago.

The company’s 1970s and 1980s projections were “at least as skillful as, those of independent academic and government models,” according to a 2023 Harvard study.

Since taking over from former CEO Rex Tillerson, Woods has walked a tightrope between acknowledging the critical problem of climate change — as well as the role of fossil fuels in helping drive it — while insisting fossil fuels must also provide the solution.

In comments before last year’s United Nations Climate Conference (COP28), Woods made a forceful case for carbon capture and storage, a technology in which the planet-heating chemicals released by burning fossil fuels are collected and stored underground.

“While renewable energy is essential to help the world achieve net zero, it is not sufficient,” he said. “Wind and solar alone can’t solve emissions in the industrial sectors that are at the heart of a modern society.”

International experts agree with the idea in the broadest strokes.

Carbon capture marks an essential component of the transition to “net zero,” in which no new chemicals like carbon dioxide or methane reach — and heat — the atmosphere, according to a report by International Energy Agency (IEA) last year.

But the remaining question is how much carbon capture will be needed, which depends on the future role of fossil fuels.

While this technology is feasible, it is very expensive — particularly in a paradigm in which new renewables already outcompete fossil fuels on price.

And the fossil fuel industry hasn’t been spending money on developing carbon capture technology, IEA head Fatih Birol wrote last year on X, the platform formerly known as Twitter.

To be part of a climate solution, Birol added, the fossil fuel industry must “let go of the illusion that implausibly large amounts of carbon capture are the solution.”

He noted that capturing and storing current fossil fuel emissions would require a thousand-fold leap in annual investment from $4 billion in 2022 to $3.5 trillion.

In his comments Tuesday, Woods argued the “dirty secret” is that customers weren’t willing to pay for the added cost of cleaner fossil fuels.

Referring to carbon capture, Woods said Exxon has “tabled proposals” with governments “to get out there and start down this path using existing technology.”

“People can’t afford it, and governments around the world rightly know that their constituents will have real concerns,” he added. “So we’ve got to find a way to get the cost down to grow the utility of the solution, and make it more available and more affordable, so that you can begin the [clean energy] transition.”

For example, he said Exxon “could, today, make sustainable aviation fuel for the airline business. But the airline companies can’t afford to pay.”

Woods blamed “activists” for trying to exclude the fossil fuel industry from the fight to slow rising temperatures, even though the sector is “the industry that has the most capacity and the highest potential for helping with some of the technologies.”

That is an increasingly controversial argument. Across the world, wind and solar plants with giant attached batteries are outcompeting gas plants, though battery life still needs to be longer to make renewable power truly dispatchable.

Carbon capture is “an answer in search of a question,” Gregory Nemet, a public policy professor at the University of Wisconsin, told The Hill last year.

“If your question is what to do about climate change, your answer is one thing,” he said — likely a massive buildout in solar, wind and batteries.

But for fossil fuel companies asking “‘What is the role for natural gas in a carbon-constrained world?’ — well, maybe carbon capture has to be part of your answer.”

In the background of Woods’s comments about customers’ unwillingness to pay for cleaner fossil fuels is a bigger debate over price in general.

This spring, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) will release its finalized rule on companies’ climate disclosures.

That much-anticipated rule will weigh in on the key question of whose responsibility it is to account for emissions — the customer who burns them (Scope II), or the fossil fuel company that produces them (Scope III).

Exxon has long argued for Scope II, based on the idea that it provides a product and is not responsible for how customers use it.

Last week, Reuters reported that the SEC would likely drop Scope III, a positive development for the companies.

Woods argued last year that SEC Scope III rules would cause Exxon to produce less fossil fuels — which he said would perversely raise global emissions, as its products were replaced by dirtier production elsewhere.

This broad idea — that fossil fuels use can only be cleaned up on the “demand side” — is one some economists dispute.

For the U.S. to decarbonize in an orderly fashion, “restrictive supply-side policies that curtail fossil fuel extraction and support workers and communities must play a role,” Rutgers University economists Mark Paul and Lina Moe wrote last year.

Without concrete moves to plan for a reduction in the fossil fuel supply, “the end of fossil fuels will be a chaotic collapse where workers, communities, and the environment suffer,” they added.

But Woods’s comments Tuesday doubled down on the claim that the energy transition will succeed only when end-users pay the price.

“People who are generating the emissions need to be aware of [it] and pay the price,” Woods said. “That’s ultimately how you solve the problem.”

#us politics#news#the hill#2024#carbon emissions#green energy#climate change#climate crisis#exxon mobil#Darren Woods#United Nations Climate Conference#COP28#carbon capture and storage#renewable energy#International Energy Agency#Fatih Birol#fossil fuels#Securities and Exchange Commission#emissions

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Saudi Arabia, the world’s leading exporter of oil, has become the biggest obstacle to an agreement at the United Nations climate summit in Dubai, where countries are debating whether to call for a phaseout of fossil fuels in order to fight global warming, negotiators and other officials said.

The Saudi delegation has flatly opposed any language in a deal that would even mention fossil fuels — the oil, gas and coal that, when burned, create emissions that are dangerously heating the planet. Saudi negotiators have also objected to a provision, endorsed by at least 118 countries, aimed at tripling global renewable energy capacity by 2030.

Saudi diplomats have been particularly skillful at blocking discussions and slowing the talks, according to interviews with a dozen people who have been inside closed-door negotiations. Tactics include inserting words into draft agreements that are considered poison pills by other countries; slow-walking a provision meant to help vulnerable countries adapt to climate change; staging a walkout in a side meeting; and refusing to sit down with negotiators pressing for a phaseout of fossil fuels.

The Saudi opposition is significant because U.N. rules require that any agreement forged at the climate summit be unanimously endorsed. Any one of the 198 participating nations can thwart a deal.

Saudi Arabia isn’t the only country raising concerns about more ambitious global efforts to fight climate change. The United States has sought to inject caveats into the fossil fuel phaseout language. India and China have opposed language that would single out coal, the most polluting of fossil fuels.

…Saudi Arabia has stood out as the most implacable opponent of any agreement on fossil fuels.

“Most countries vary on the degree or speed of how fast you get out of fossil fuels,” said Linda Kalcher, a former climate adviser to the United Nations who has been in negotiating rooms this week. Saudi Arabia, she said, “doesn’t even want to have the conversation.”

Saudi officials did not respond to requests for comment.

(continue reading)

#politics#cop28#climate change#global warming#climate crisis#saudi arabia#eau#environment#fossil fuels#un climate summit#united nations#united nations climate change conference#environmental activism

186 notes

·

View notes

Text

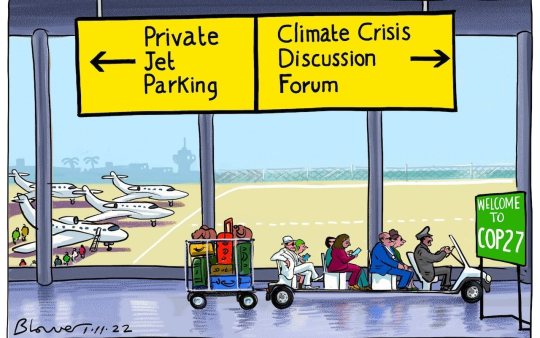

COP27: World Climate Waste of Time

The climate changes, politicians do not.

l (x)(x)(x) l title & quote fr. AGO (2nd art)

#cop27#art#cartoons#climate change#united nations#un#egypt#cartoon#global warming#environment#planets#earth#climate crisis#climate change conference#private jet

205 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is so dumb tbh.

One of the biggest oil providers in the world hosting the most important climate conference...

#cop28#climate conference#un environment#un#united nations#climate change#climate crisis#climateaction#crisis#environmental activism#activism#climate activism#activist#climate science#plastic#uae#united arab emirates#oil#petroleum#carbon dioxide emissions#co2#co2 gas#carbon dioxide#carbon tax

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

BOYCOTT COP28

As with everything in the UAE, COP28 is a mirage of green washing. Getting there by plane - the top polluting industry, made worse by private jets, is only the beginning of the paradox of attending. The tourism industry, heavily reliant there on air conditioning, releases GHGs by the tons, food waste and a proliferation of plastics. The ambient air is often at 150 on the AQI, where elsewhere normal levels are at 25. Next is the use of Israeli lobby firms to help the UAE with its human rights record in Europe where EU politicians are allegedly bribed in Red Crescent envelopes, which still conveniently leaves out the sex trade (Porta Potty) and degradation of women albeit - as is always the excuse, renumerated handsomely (for dressing as nuns ripping bibles mid-sex!). Yes, employing human rights offenders to combat its image as human rights abuser is as cynical as the UAE leadership is. But getting at the heart of abuses is what Little Sparta has accomplished in Yemen, Libya, Tunisia, Sudan, and elsewhere with mercenaries like the Wagner group or with UAE-based nutjob Erik Prince. Muslims killed, starved or displaced by the thousands if not millions to the glory of a leader whose protection is guaranteed by London, UK for services rendered to the (non-Muslim) monarchy by its repression and persecution of all things Arab Spring and democracy... couched in "anti-terrorism". Of course 🙄. This is the place that jailed Jamal Khashoggi's lawyer for "insulting the state" and lured & kidnapped the Hotel Rwanda hero recently released. Its judicial system is at the whim of its leaders. Fast forwarding to the UAE's planned fossil fuel expansion by 2050 and the Paris Accord may as well go to Dubai to die in December 2023.

#boycott cop28#uae#mbz#climate change#united nations#gold mafia#antonio guterres#climate conference#israeli occupation#human rights#israeli apartheid#greta thunberg#palestine#palestinians#illegal settlements#shireen abu akleh#free palestine#cop28#expo2020#dubai#fazza#princess haya#sheikha latifa#jamal khashoggi#wagner group#mercenaries#gold#sudan#ukraine#muslim

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

#United Nations#migratory species#wildlife conservation#climate change#habitat loss#pollution#illegal hunting#illegal fishing#International Union for Conservation of Nature's Red List#Wildlife Conservation Society#U.N. Biodiversity Conference#Amazon River#conservation#wildlife#UN Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

In November, world leaders at the most recent big climate meeting, known as COP27, agreed to set up a “loss and damage” fund, bankrolled by rich countries, to help poor countries harmed by climate change. Now comes the hard part of figuring out the details: This week, a special United Nations committee set up to plan the fund will meet for the first time, in Luxor, Egypt. Delegates will start negotiating which nations will be able to draw from the fund, where it will be housed, where the money will come from, and how much each country should pitch in. At this point, the fund is “an empty bucket,” says Lien Vandamme, a senior campaigner at the nonprofit Center for International Environmental Law, who is in Egypt for the negotiations. “Everything is still open.” Other meetings will follow, and the committee will make its recommendations to the world this fall in Dubai at COP28.

If the past several decades of climate negotiations are anything to go on, the loss-and-damage fund will be poorly endowed, or filled with money that got moved over from some other fund and relabeled, or in the form of loans rather than grants. If that happens, it will likely be perceived by poorer nations as yet another inadequate response by the same countries that messed up the climate in the first place. And those that are wronged are unlikely to simply suffer in silence.

The loss-and-damage fund would be separate from what is currently the dominant form of climate funding that flows to the global South: money to help low-income nations reduce their emissions. And it would also be separate from “adaptation,” money to help areas prepare for disasters or avoid the harms of warming. Instead, the new fund would be provided by rich countries to compensate poor countries that have already suffered losses. In a word, it would be reparations.

The agreement to establish a fund for this purpose was initially opposed by some rich countries. The U.S. climate envoy John Kerry said in the fall that helping the developing world cope with climate change is “a moral obligation”—but he wanted that help to flow through existing funds and institutions, including the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund. Developing countries, however, demanded a new, dedicated fund, and they ultimately prevailed. Almost all the details were left to be finalized at COP28 in Dubai, after the committee has worked to iron out specifics. But by agreeing that a loss-and-damage fund should exist, countries seem to be reluctantly acknowledging that they bear some moral accountability for climate change. “It is very clear that developed countries have a historical responsibility,” says Liane Schalatek, a climate-finance expert at the Heinrich Böll Foundation in Washington, D.C., who is also in Luxor this week.

Funds are especially needed for the “day after” problems—the ongoing work of rebuilding and recovering after a flood or a heat wave is over and the emergency foreign aid has dried up, Mohamed Nasr, Egypt’s delegate to this week’s meeting, told me. People don’t just need tarp tents and bowls of rice. They need “social support, a way to return livelihoods,” Nasr said.

But how much is enough? One analysis suggests that the true scale of the financial losses due to climate change outside of the West may be as much as $580 billion a year by 2030, and some groups are considering a figure in that ballpark to be the minimum acceptable amount. Another analysis estimated that America owed $20 billion for global climate losses in 2022, a number that would rise to about $117 billion annually by 2030. Nasr demurred on naming specific amounts, suggesting that the workings of the fund be negotiated first. The needs are enormous, and mentioning figures at this point would only “scare people,” he said. “If you put a number on at the beginning, the focus will only be on the number,” he told me. But he did add that “it will be in the billions.”

Given that the standing UN goal for all types of climate funding from rich countries to poorer ones—$100 billion—has never been met, filling the loss-and-damage fund with hundreds of billions of dollars feels like an almost impossible lift. “It will be a huge challenge to get countries to agree on the amount that is needed,” says Leia Achampong of the European Network on Debt and Development. For many delegates from the global South, a key demand is that the fund not come in the form of loans. Many poor countries, including Pakistan, are already dealing with debt, which is affecting their ability to provide for their own citizens. More loans would just add to this debt burden. “If a country is in debt, you have the World Bank and the IMF calling for austerity, and the first thing that usually goes is the social safety net,” Schalatek told me.

— The West Agreed to Pay Climate Reparations. That Was the Easy Part

#emma marris#the west agreed to pay climate reparations. that was the easy part#current events#climate change#global warming#environmentalism#climate justice#economics#politics#debt#international relations#2022 united nations climate change conference#cop27#2023 united nations climate change conference#cop28#egypt#pakistan#lien vandamme#john kerry#liane schalatek#mohamed nasr#leia achampong#center for international environmental law#heinrich böll foundation#eurodad

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dubai’s Expo City and the Al Wall Dome, where the United Nations climate conference started on Thursday.

(Photo: Kamran Jebreili/Associated Press)

Fossil Fuels and Frustration at COP28

The United Arab Emirates, one of the world’s biggest oil producers, is hosting this year’s COP28 climate summit.

World leaders, delegates and negotiators from almost every country on the planet will work on redoubling their efforts to combat climate change.

While hopes are high that countries might find ways to rapidly reduce greenhouse gases and limit the use of coal, oil and gas, the reality is that fossil fuel emissions are still growing. Meanwhile, the destructive effects of climate change are getting worse, with floods, fires, droughts and storms ravaging every corner of the globe.

Frustrations with the U.N. process, and the plodding pace of progress, are running high.

By David Gelles

The New York Times- November 30, 2023

•

•

Sultan Al Jaber, president of the COP28 climate summit 2023, at the talks on Monday.

(Photo: Kamran Jebreili/Associated Press)

UAE’s Sultan Al Jaber faces a firestorm over fossil fuels

By Lisa Friedman

The New York Times - December 4, 2023

The Emirati oil executive leading the global climate summit faced intense criticism on Monday over his claim that there was “no science” that shows fossil fuels must be phased out to prevent disastrous levels of global temperature increases.

Sultan Al Jaber, the COP28 president and chief executive of the state-owned oil company Adnoc, said in a newly surfaced video there was “no science out there, or no scenario out there, that says that the phaseout of fossil fuel is what’s going to achieve 1.5.”

Scientists say if temperatures rise more than 1.5 degrees Celsius over preindustrial levels, humans would struggle to adapt to increasingly severe storms, drought, heat and rising sea levels.

Al Jaber made the controversial comments two weeks ago, but they only came to light on Sunday when they were reported by The Guardian.

“Please, help me, show me a road map for a phaseout of fossil fuels that will allow for sustainable socioeconomic development, unless you want to take the world back into caves,” Al Jaber told a panel discussion led by Mary Robinson, the former president of Ireland, who is now a prominent climate advocate.

His remarks set off a firestorm at the climate talks being held in Dubai, known as COP28.

Former U.S. Vice President Al Gore, who has called for fossil fuels to be replaced with wind, solar and other renewable energy, assailed Al Jaber.

“From the moment this absurd masquerade began, it was only a matter of time before his preposterous disguise no longer concealed the reality of the most brazen conflict of interest in the history of climate negotiations,” Gore said in an email. “Obviously, the world needs to phase out fossil fuels as quickly as possible.”

On Monday, a defiant Al Jaber suggested he did not say what he can be heard saying on the video. And he indicated that anyone who claimed otherwise was trying to undermine his leadership of COP28.

In front of a packed and hastily arranged news conference, Al Jaber appeared to take the criticism personally and described his background as an economist and an engineer. “I respect the science in everything I do,” he said.

“I have said over and over that the phase-down and the phaseout of fossil fuels is inevitable,” Al Jaber said.

He insisted that he has called many times for a phase out of fossil fuels and said that his efforts to champion climate change had been ignored by the media.

Al Jaber appeared aggrieved, taking issue with “one statement, taken out of context with misrepresentation and misinterpretation that gets maximum coverage.”

The planet has already warmed about 1.2 degrees since the industrial revolution, driven by the burning of coal, oil and gas.

Jim Skea, the chairman of the U.N.’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, said on Monday while sitting next to Al Jaber that fossil fuels would need to be “greatly reduced” by 2050 in order to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees. Coal plants without technology to capture and store emissions would need to be phased out completely, he said.

The fossil fuel industry has responded to suggestions of a phaseout by saying that technology could capture and store carbon emissions, which would allow it to continue to operate. But scientists widely agree that the technologies that the oil industry is depending upon, like carbon capture and storage, cannot be deployed at the scale or pace required to avoid the worst impacts of climate change.

•

•

Sultan Al Jaber: ‘There is no science out there that says that the phase-out of fossil fuel is what’s going to achieve 1.5C.’

(Photo: Anadolu/Getty Images)

Cop28 president says there is ‘no science’ behind demands for phase-out of fossil fuels

The president of Cop28, UAE’s Sultan Al Jaber, has claimed there is “no science” indicating that a phase-out of fossil fuels is needed to restrict global heating to 1.5C, the Guardian and the Centre for Climate Reporting can reveal.

Al Jaber also said a phase-out of fossil fuels would not allow sustainable development “unless you want to take the world back into caves”.

The comments were “incredibly concerning” and “verging on climate denial”, scientists said, and they were at odds with the position of the UN secretary general, António Guterres.

By Damian Carrington and Ben Stockton

The Guardian - 3 December 2023

•

#Climate crisis#COP28 - 28th United Nations Climate Change Conference 2023#UAE - United Arab Emirates#Sultan Al Jaber#Fossil fuels#Oil#Gas#Coal#Mary Robinson#Science

0 notes

Text

“Confluence Of Conscience: Uniting Faith Leaders For Planetary Resurgence” Conference.

Dear friends,

Your gathering in the runup to COP28 comes at a critical moment for humanity and the planet we call home.

Climate breakdown is all around us.

Record-shattering heat and wildfires.

Melting glaciers and rising seas.

Epic floods and storms.

All hitting the vulnerable hardest — those least responsible for this crisis.

People and planet need action.

Action to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees.

Action to phase down planet-killing fossil fuels and ramp up the renewables revolution.

Action to support developing countries and deliver climate justice, with finance for renewables, adaptation and loss and damage.

And action from leaders at COP28 to deliver a strong outcome that makes these ambitions a reality.

As faith leaders, you are part of this essential work.

We need your moral voice and spiritual authority to summon the conscience of leaders, awaken their ambition, and inspire them to do what is needed at COP28 to save our one and only home.

And we’re counting on your support to give this issue the urgency it needs among the wider public.

The path is clear.

The time is now.

And we need all hands on deck.

Thank you for standing in solidarity, and lending your moral voice and great influence to this essential cause.

#Conferences#faith leaders#united nations secretary-general#cop18#Confluence of conscience#conscience#spiritual leaders#changing climate

0 notes

Text

Last year, Pakistan was hit with floods so devastating that they were hard to comprehend. In some areas, 15 inches of rain fell in a single day. And the rain went on for months, inundating one-third of the country, spreading disease, and displacing nearly 8 million people. Six months later, Pakistan is still in crisis—nearly 2 million people are living near stagnant floodwater. Pakistan has estimated that it needs about $16.3 billion to recover from the floods, a sum that does not take into account so many ripple effects of the crisis: grief over those who died, education abruptly ended, the struggles of girls married off young as their families coped with a sudden plunge into poverty.

But these floods were not a “natural disaster.” The monsoon rains were up to 50 percent more intense than they would have been without climate change. So although Pakistan has to foot this bill, or at least most of it, the country bears little responsibility: Pakistan contributes less than 1 percent of global greenhouse-gas emissions, while the United States is the world’s second-biggest emitter, accountable for about 20 percent of emissions since 1850. But there is no mechanism for the United States or any other country to pay for the loss and damage that it is at least partially responsible for.

That may be changing. In November, world leaders at the most recent big climate meeting, known as COP27, agreed to set up a “loss and damage” fund, bankrolled by rich countries, to help poor countries harmed by climate change. Now comes the hard part of figuring out the details: This week, a special United Nations committee set up to plan the fund will meet for the first time, in Luxor, Egypt. Delegates will start negotiating which nations will be able to draw from the fund, where it will be housed, where the money will come from, and how much each country should pitch in. At this point, the fund is “an empty bucket,” says Lien Vandamme, a senior campaigner at the nonprofit Center for International Environmental Law, who is in Egypt for the negotiations. “Everything is still open.” Other meetings will follow, and the committee will make its recommendations to the world this fall in Dubai at COP28.

If the past several decades of climate negotiations are anything to go on, the loss-and-damage fund will be poorly endowed, or filled with money that got moved over from some other fund and relabeled, or in the form of loans rather than grants. If that happens, it will likely be perceived by poorer nations as yet another inadequate response by the same countries that messed up the climate in the first place. And those that are wronged are unlikely to simply suffer in silence.

The loss-and-damage fund would be separate from what is currently the dominant form of climate funding that flows to the global South: money to help low-income nations reduce their emissions. And it would also be separate from “adaptation,” money to help areas prepare for disasters or avoid the harms of warming. Instead, the new fund would be provided by rich countries to compensate poor countries that have already suffered losses. In a word, it would be reparations.

The agreement to establish a fund for this purpose was initially opposed by some rich countries. The U.S. climate envoy John Kerry said in the fall that helping the developing world cope with climate change is “a moral obligation”—but he wanted that help to flow through existing funds and institutions, including the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund. Developing countries, however, demanded a new, dedicated fund, and they ultimately prevailed. Almost all the details were left to be finalized at COP28 in Dubai, after the committee has worked to iron out specifics. But by agreeing that a loss-and-damage fund should exist, countries seem to be reluctantly acknowledging that they bear some moral accountability for climate change. “It is very clear that developed countries have a historical responsibility,” says Liane Schalatek, a climate-finance expert at the Heinrich Böll Foundation in Washington, D.C., who is also in Luxor this week.

Funds are especially needed for the “day after” problems—the ongoing work of rebuilding and recovering after a flood or a heat wave is over and the emergency foreign aid has dried up, Mohamed Nasr, Egypt’s delegate to this week’s meeting, told me. People don’t just need tarp tents and bowls of rice. They need “social support, a way to return livelihoods,” Nasr said.

But how much is enough? One analysis suggests that the true scale of the financial losses due to climate change outside of the West may be as much as $580 billion a year by 2030, and some groups are considering a figure in that ballpark to be the minimum acceptable amount. Another analysis estimated that America owed $20 billion for global climate losses in 2022, a number that would rise to about $117 billion annually by 2030. Nasr demurred on naming specific amounts, suggesting that the workings of the fund be negotiated first. The needs are enormous, and mentioning figures at this point would only “scare people,” he said. “If you put a number on at the beginning, the focus will only be on the number,” he told me. But he did add that “it will be in the billions.”

Given that the standing UN goal for all types of climate funding from rich countries to poorer ones—$100 billion—has never been met, filling the loss-and-damage fund with hundreds of billions of dollars feels like an almost impossible lift. “It will be a huge challenge to get countries to agree on the amount that is needed,” says Leia Achampong of the European Network on Debt and Development. For many delegates from the global South, a key demand is that the fund not come in the form of loans. Many poor countries, including Pakistan, are already dealing with debt, which is affecting their ability to provide for their own citizens. More loans would just add to this debt burden. “If a country is in debt, you have the World Bank and the IMF calling for austerity, and the first thing that usually goes is the social safety net,” Schalatek told me.

A central issue going into the meeting in Egypt is that, despite broad agreement that rich countries responsible for the most emissions should pay in and that poor countries feeling the brunt of the effects should receive the funds, the globe cannot be neatly divided into just two categories—“developed” and “developing.” The trickiest case is undoubtedly China. Historically classified as a developing country, China is getting richer by the month and has emitted 11 percent of historical emissions, second only to the United States. At COP27, a coalition of developing countries rallied around China’s claim that it should be a recipient rather than a donor, to the consternation of the European negotiators. The U.S. will likely be loath to lavish money on a fund that China can draw from. Another outstanding question is whether contributions to the fund will be legal obligations rather than just voluntary donations. Anything with legal teeth would require congressional approval in the U.S., which would not be easy. (The State Department did not respond to a request for comment on the loss-and-damage negotiations.)

If the loss-and-damage fund are skimpy, communities and nations will likely seek restitution for their losses through national and international courts. An early test case began in 2015, when a Peruvian farmer sued the German energy giant RWE. The farmer, Saúl Luciano Lliuya, says his home is at risk of being washed away by meltwater from a glacier, and he wants the company to pay 0.47 percent of his adaptation costs, on the basis of a study that attributes that fraction of emissions to the company’s activities. RWE has denied culpability, and the case is ongoing. In an example of targeting nations rather than companies, Indigenous people from four low-lying Australian islands—Boigu, Poruma, Warraber and Masig—submitted a petition to the UN Human Rights Committee arguing that the country had done little to stop the climate change threatening their homes. In September, the committee agreed, ordering Australia to compensate the islanders for their losses.

But legal action might actually be a best-case scenario for the West. Poor, debt-ridden countries struggling with a climate crisis do not make for a stable globe. In 2021, a U.S. Department of Defense report on climate change warned that “the physical and social impacts of climate change transcend political boundaries, increasing the risk that crises cascade beyond any one country or region.” People who lose homes and livelihoods to climate-caused disasters will do what they can to improve their situation. As far back as 1995, the Bangladeshi dignitary Atiq Rahman warned, “if climate change makes our country uninhabitable, we will march with our wet feet into your living rooms.” Hundreds of millions of people may be displaced by 2050.

Mass migrations, resource scarcity, and poverty can lead to global conflicts. No country, no matter how rich, can build a seawall high enough to keep out that kind of chaos. If rich countries cannot be moved to lavishly fund the loss-and-damage bucket by appeals to justice, perhaps they will be moved by what has long been a more reliable motivating force: fear.

#current events#climate change#global warming#environmentalism#economics#climate justice#politics#american politics#chinese politics#2022 united nations climate change conference#cop27#loss and damage#usa#china#pakistan

1 note

·

View note

Quote

Most Asian countries prioritised adaptation in climate action plans but there is a need to do more to achieve early warnings for all, the authors of the report wrote. Strengthening the early warning systems can play a pivotal role in taking anticipatory action, enhancing preparedness and reducing the impact of these hazards, it said. Data on loss and damage is required more than ever as funding for loss & damage has made it to COP27 agenda for the first time ever in the history of UN climate negotiations. A realistic estimate can still be made about the number of days the country recorded extreme weather events.

Kiran Pandey, ‘Extreme weather hits economies, hurts Asia most: WMO report’, Down To Earth

#Down To Earth#Kiran Pandey#Asian countries#adaptation#climate action plans#early warning systems#natural hazards#2022 United Nations Climate Change Conference or Conference of the Parties of the UNFCCC#COP27#UN climate negotiations#extreme weather events

1 note

·

View note

Text

Worsening realities in Oceania show need for continued dialogue

Worsening realities in Oceania show need for continued dialogue

Worsening realities for Oceania – such as sea level rise and food security – are leading to urgent calls for help from those most affected. They’re not leading to urgent action from those most able to help though.

This year’s COP27 meetings reviewed progress of commitments to pledges made at earlier United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change meetings. It found many countries have…

View On WordPress

#Australian Catholic University (ACU)#COP27#Federation of Catholic Bishops&039; Conferences of Oceania (FCBCO)#Our Ocean Home#United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change

0 notes

Text

Young people just got a louder voice on global climate issues — and could soon be shaping policy

Young people just got a louder voice on global climate issues — and could soon be shaping policy

COP27 was another milestone for young climate activists as they became official climate policy stakeholders under the ACE Action Plan.

Photo by Dominika Zarzycka/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images

Young people have long been at the forefront of discussions and activism around climate change.

This year’s COP27 was another milestone for them — they became official stakeholders in climate…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Tarek Kapiel: The significance of scientific culture and education in raising awareness of the climate change

Tarek Kapiel: The significance of scientific culture and education in raising awareness of the climate change

It is well known that climate change poses serious threats to human civilization, and it appears that if we take full advantage of the occasion to host the United Nations Climate Change Conference “COP 27” in Egypt in the coming weeks, it will provide us with a beneficial opportunity to build a more sustainable future for the Egyptian people and to help educate students and the entire Egyptian…

View On WordPress

#Cairo University#COP 27#human civilization#Tarek Kapiel#the Academy of Scientific Research#the climate change#the United Nations Climate Change Conference

0 notes

Text

Bad Faith, Espionage & Propaganda, from COP28 host:

As Cop emails are read out by oil firm...

And a fake PR campaign props the worst choice for UN COP host, an oil exec... 🙄

#boycott cop28#cop28#united nations#sheldon whitehouse#congress#john kerry#climate conference#environment#adnoc#espionage#troll army

0 notes

Text

No-paywall version.

"You can never really see the future, only imagine it, then try to make sense of the new world when it arrives.

Just a few years ago, climate projections for this century looked quite apocalyptic, with most scientists warning that continuing “business as usual” would bring the world four or even five degrees Celsius of warming — a change disruptive enough to call forth not only predictions of food crises and heat stress, state conflict and economic strife, but, from some corners, warnings of civilizational collapse and even a sort of human endgame. (Perhaps you’ve had nightmares about each of these and seen premonitions of them in your newsfeed.)

Now, with the world already 1.2 degrees hotter, scientists believe that warming this century will most likely fall between two or three degrees. (A United Nations report released this week ahead of the COP27 climate conference in Sharm el Sheikh, Egypt, confirmed that range.) A little lower is possible, with much more concerted action; a little higher, too, with slower action and bad climate luck. Those numbers may sound abstract, but what they suggest is this: Thanks to astonishing declines in the price of renewables, a truly global political mobilization, a clearer picture of the energy future and serious policy focus from world leaders,

we have cut expected warming almost in half in just five years.

...Conventional wisdom has dictated that meeting the most ambitious goals of the Paris agreement by limiting warming to 1.5 degrees could allow for some continuing normal, but failing to take rapid action on emissions, and allowing warming above three or even four degrees, spelled doom.

Neither of those futures looks all that likely now, with the most terrifying predictions made improbable by decarbonization and the most hopeful ones practically foreclosed by tragic delay. The window of possible climate futures is narrowing, and as a result, we are getting a clearer sense of what’s to come: a new world, full of disruption but also billions of people, well past climate normal and yet mercifully short of true climate apocalypse.

Over the last several months, I’ve had dozens of conversations — with climate scientists and economists and policymakers, advocates and activists and novelists and philosophers — about that new world and the ways we might conceptualize it. Perhaps the most capacious and galvanizing account is one I heard from Kate Marvel of NASA, a lead chapter author on the fifth National Climate Assessment: “The world will be what we make it.” Personally, I find myself returning to three sets of guideposts, which help map the landscape of possibility.

First, worst-case temperature scenarios that recently seemed plausible now look much less so, which is inarguably good news and, in a time of climate panic and despair, a truly underappreciated sign of genuine and world-shaping progress...

[I cut number two for being focused on negatives. This is a reasons for hope blog.]

Third, humanity retains an enormous amount of control — over just how hot it will get and how much we will do to protect one another through those assaults and disruptions. Acknowledging that truly apocalyptic warming now looks considerably less likely than it did just a few years ago pulls the future out of the realm of myth and returns it to the plane of history: contested, combative, combining suffering and flourishing — though not in equal measure for every group...

“We live in a terrible world, and we live in a wonderful world,” Marvel says. “It’s a terrible world that’s more than a degree Celsius warmer. But also a wonderful world in which we have so many ways to generate electricity that are cheaper and more cost-effective and easier to deploy than I would’ve ever imagined. People are writing credible papers in scientific journals making the case that switching rapidly to renewable energy isn’t a net cost; it will be a net financial benefit,” she says with a head-shake of near-disbelief. “If you had told me five years ago that that would be the case, I would’ve thought, wow, that’s a miracle.”"

-via The New York Times Magazine, October 26, 2022

#climate change#global warming#renewable energy#climate anxiety#climate crisis#humanity#green energy#green future#apocalypse#natural disasters#good news#hope#research#hope posting

2K notes

·

View notes