#united tailoresses' society

Text

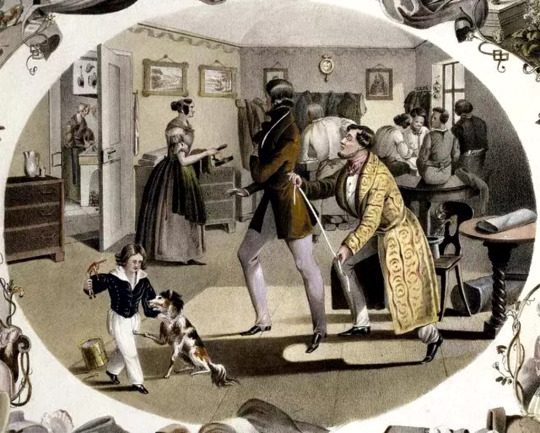

'La M. de la Corsets': c. 1832 lithograph showing a dressmaker or tailoress and client. The undergarments depicted include sleeve-plumpers.

1830s Thursday: Big sleeves, and even bigger dreams for women’s rights.

The growing vulnerability of working women in industrial society provoked a forceful response. In 1825 hundreds of them went out on strike against New York City clothing houses. In 1831 these same women organized themselves into a mass-membership United Tailoresses’ Society. At a time when journeymen were still devoting their political efforts to a defense of artisanal prerogatives in the master’s shop, these “tailoresses” (the appellation itself testified to an advanced degree of industrial consciousness, excluding as it did the more traditional dressmaking of the “sempstress”) already understood that in a capitalist economy no aspect of the work relationship remained non-negotiable. [...]

No one can help us but ourselves, Sarah Monroe, a leader of the United Tailoresses’ Society, declared. Tailoresses should consequently organize a trade union with a constitution, a plan of action, and a strike fund. Only then could we “come before the public in defense of our rights.” The Wollstonecraftian rhetoric was conscious. Lavinia Wright, the society’s secretary, argued that the tailoresses’ low wages and hard-pressed circumstances were a direct result of the way power was organized throughout society to ensure women’s subordination in all social relations.

— Michael Zakim, Ready-Made Democracy: A History of Men's Dress in the American Republic, 1760-1860

I was disappointed in my search for pictures of Sarah Munroe, Lavinia Wright, or really anything to do with the United Tailoresses’ Society. One online article outright stated, “We know very little about this speaker, Sarah Monroe, other than that she was a garment worker and president of the newly formed United Tailoress Society -- the first women-only union in the United States.”

I am in awe of this working-class woman, Sarah Monroe, who is quoted by Michael Zakim as saying in 1831:

It needs no small share of courage for us, who have been used to impositions and oppression from our youth up to the present day, to come before the public in defense of our rights; but, my friends, if it is unfashionable for the men to bear oppression in silence, why should it not also become unfashionable with the women?

'The Tailor's Shop': 1838 lithograph by Carl Kunz and Johann Geiger

#1830s#fashion history#labor history#labour history#us history#sarah monroe#Eighteen-Thirties Thursday#united tailoresses' society#michael zakim#women's history#also i have been sleeping on michael zakim's book it's really good#there were many strikes by female garment workers in the time period#amazingly forward-thinking they were trying to get sick pay and retirement benefits#they also campaigned against prison labour#tailors#dress history#inequality#industrial relations#19th century

379 notes

·

View notes

Photo

676 notes

·

View notes

Text

Stewardess and other -ess words

Q: How did English, a fundamentally nongendered language, get the word “stewardess,” a gendered term that’s now being replaced in our gender-sensitive era by the unisex “flight attendant”? What’s wrong with using “steward” for both sexes?

A: We’ll have more to say later about the old practice of adding “-ess” to nouns to feminize them. As we’ve written before on the blog, the current trend is in the other direction.

Modern English tends to favor the original, gender-free nouns for occupations—words like “mayor,” “author,” “sculptor,” and “poet” in place of “mayoress,” “authoress,” “sculptress,” “poetess,” and so on.

But first let’s look at “stewardess,” which is probably a much older word than you think.

It first appeared in writing in 1631 to mean a female steward (that is, a caretaker of some kind), and it was used for hundreds of years in caretaking, managerial, or administrative senses.

Only in later use did “stewardess” come to mean a female attendant on a ship (a sense first recorded in 1834), a train (1855), or a plane (1930).

“Stewardess” was of course derived from the gender-free noun “steward,” which is very old.

The Oxford English Dictionary dates written evidence of “steward” (stigweard in Old English) back to 955 or earlier, and notes that it was created within English, not derived from other sources.

“The first element is most probably Old English stig,” which means “a house or some part of a house,” Oxford says, noting that the Old English stigwita meant “house-dweller.”

In its earliest uses, the word meant someone who manages the domestic affairs of a household, and it later took on more official and administrative meanings in business, government, and the church.

The femininized “stewardess,” defined in the OED as “a female who performs the duties of a steward,” was first recorded in The Spanish Bawd, James Mabbe’s 1631 translation of a “tragicke-comedy” by Fernando de Rojas:

“O variable fortune … thou Ministresse and high Stewardesse of all temporal happinesse.”

We might be tempted to attribute that example to rhyme alone. But we found two more appearances of “stewardesse” in a religious work that was probably written in 1631 or earlier and was published in 1632.

These come from Henry Hawkins’s biography of a saint, The History of S. Elizabeth Daughter of the King of Hungary. Because Elizabeth gave her fortune to the poor, the author refers to her as God’s “trusty Stewardesse &; faithfull Dispensatress of his goods” and “this incomparable Stewardesse of Christ.”

Until the early 19th century, “stewardess” continued to be used in the various ways “steward” was used for a man. For example, the OED cites an 1827 usage by Thomas Carlyle in German Romance: “She was his … Castle-Stewardess.” (The book is an anthology of German romances, and the example is from an explanatory footnote by Carlyle.)

But as the old uses of “stewardess” died away, a new one developed. People began using “stewardess” in the 1830s to mean (like “steward” before it) a woman working aboard a ship.

The OED defines this use of “stewardess” as “a female attendant on a ship whose duty it is to wait on the women passengers.”

The earliest example we’ve found is from an 1834 news article about a shipwreck that left only six people alive, a passenger named Goulding and five crew members:

“Mr. Goulding and the stewardess floated ashore upon the quarter deck.” (From the Oct. 16, 1834, issue of a New York newspaper, the Mercury.)

The OED’s earliest citation is a bit later: “Mrs. F. and I were the only ladies on board; and there was no stewardess” (from Harriet Martineau’s book Society in America, 1837).

The use of the word in rail travel came along a couple of decades later. We found this example in a news account of a train wreck:

“A train hand, named Miller, had his leg broken above the ankle, and seemed much injured. Margaret, the stewardess of the train, was likewise bruised.” (From the Daily Express of Petersburg, Va., Oct. 30, 1855.)

Soon afterward, on July 29, 1858, a travel article in the Wheeling Daily Intelligencer in West Virginia noted that on the Petersburg & Weldon Railway, a “stewardess travels with each train to wait on the lady passengers—serve ice water to them—hold their babies and other baggage occasionally.” (Note the reference to “babies and other baggage”!)

The earliest example we’ve found of “stewardess” meaning an aircraft attendant appeared in the New York Times on July 20, 1930. The reporter describes firsthand his experience aboard a flight from San Francisco to Chicago:

“And then there is Miss Inez Keller, stewardess or rather traveling hostess. The Boeing system has solved the problem of looking after the passengers by putting girls on all the liners.”

Later that year, an Australian newspaper ran this item: “A successful trial flight was made with the finest and largest passenger air liners in the world, each having luxurious accommodation for 38 passengers, with smoking saloon two pilots, steward and stewardess.” (From the Western Herald, Nov. 18, 1930.)

The OED’s first example appeared the following year in a photo caption published in United Airlines News (Aug. 5, 1931): “Uniformed stewardesses employed on the Chicago-San Diego divisions of United. The picture shows the original group of stewardesses employed.”

Oxford defines the newest sense of “stewardess” this way: “A female attendant on a passenger aircraft who attends to the needs and comfort of the passengers.” It adds that the word also means “a similar attendant on other kinds of passenger transport.”

This brings us to the larger subject—the use of the suffix “-ess” to form what the OED calls “nouns denoting female persons or animals.”

The ancestral source of “-ess,” according to etymologists, is the Greek -ισσα (-issa in our alphabet), which passed into Late Latin (-issa), then on into the Romance languages, including French (-esse).

In the Middle Ages, according to OED citations, English adopted many French words with their feminine endings already attached, including “countess” (perhaps before 1160), “hostess” (circa 1290), “abbess” (c. 1300), “lioness” (1300s), “mistress” (c. 1330), “arbitress” (1340), “enchantress” (c. 1374), “devouress” (1382), “sorceress” (c. 1384), “duchess” (c. 1385), “princess” (c. 1385), “conqueress” (before 1400), and “paintress” (c. 1450).

Some other English words, though not borrowed wholly from French, were modeled after the French pattern, like “adulteress” (before 1382) and “authoress” (1478).

And in imitation of such words, “-ess” endings were added to a few native words of Germanic origin, forming “murderess” (c. 1200); “goddess” (some time before 1387), and obsolete formations like “dwelleress” and “sleeresse” (“slayer” + “-ess”), both formed before 1382.

As the OED explains, writers of the 1500s and later centuries “very freely” invented words ending in “-ess,” but “many of these are now obsolete or little used, the tendency of modern usage being to treat the agent-nouns [ending] in –er, and the nouns indicating profession or occupation, as of common gender, unless there be some special reason to the contrary.”

Some of the dusty antiques include “martyress” (possibly 1473), “doctress” (1549), “buildress” (1569), “widowess” (1596), “creditress” (1608), “gardeneress” (before 1645), “tailoress” (1654), “farmeress” (1672), “vinteress” (1681), “auditress” (1667), “philosophess” (1668), “professoress” (1744), “chiefess” (1778), “editress” (1799), and “writeress” (1822).

Still seen, though rapidly going out of fashion, are “hostess” (c. 1290), “authoress” (1478), “poetess” (1531), “heiress” (1656), and “sculptress” (1662).

Of the few such occupational words that are still widely used, perhaps the most common are “actress” (1586) and “waitress” (c. 1595). These “-tress” endings, the OED says, “have in most cases been suggested by, and may be regarded as virtual adaptations of, the corresponding French words [ending] in -trice.”

In conclusion, “stewardess” was created at a time—in the 1600s—when English writers created all sorts of what the OED calls “feminine derivatives expressing sex.” It was also a time when educated English speakers regarded their native tongue as inferior to French and Latin, the gendered languages that were the lingua franca of nobles, clergy, and scholars.

Now “stewardess,” like so many of those feminized nouns, is rapidly becoming obsolete. But unlike the others, it hasn’t been replaced by a unisex “steward.”

Why? We don’t know the answer. But for whatever reason, as “stewardess” has fallen out of favor it’s taken “steward” down with it—at least in reference to air travel.

The usual replacement, “flight attendant,” showed up in the late 1940s, and passed “stewardess” in popularity in the late 1990s, according to Google’s Ngram Viewer.

The earliest example we’ve found for “flight attendant” is from the Jan. 26, 1947, issue of the Santa Cruz, Calif., Sentinel about a Hong Kong plane crash in which all four people were killed:

“The company listed those aboard as Capt. O. T. Weymouth, an American pilot, and a crew of three Filipinos, including Miss Lourdes Chuidian, flight attendant.”

Help support the Grammarphobia Blog with your donation.

And check out our books about the English language.

Subscribe to the Blog by email

Enter your email address to subscribe to the Blog by email. If you are an old subscriber and not getting posts, please subscribe again.

Email Address

/*

Custom functionality for safari and IE

*/

(function( d ) {

// In case the placeholder functionality is available we remove labels

if ( ( ‘placeholder’ in d.createElement( ‘input’ ) ) ) {

var label = d.querySelector( ‘label[for=subscribe-field-461]’ );

label.style.clip = ‘rect(1px, 1px, 1px, 1px)’;

label.style.position = ‘absolute’;

label.style.height = ‘1px’;

label.style.width = ‘1px’;

label.style.overflow = ‘hidden’;

}

// Make sure the email value is filled in before allowing submit

var form = d.getElementById(‘subscribe-blog-461’),

input = d.getElementById(‘subscribe-field-461’),

handler = function( event ) {

if ( ” === input.value ) {

input.focus();

if ( event.preventDefault ){

event.preventDefault();

}

return false;

}

};

if ( window.addEventListener ) {

form.addEventListener( ‘submit’, handler, false );

} else {

form.attachEvent( ‘onsubmit’, handler );

}

})( document );

from Blog – Grammarphobia https://www.grammarphobia.com/blog/2018/10/ess-words.html

0 notes

Text

Womens suffrage

On 19 September 1893 the governor, Lord Glasgow, signed a new Electoral Act into law. As a result of this landmark legislation, New Zealand became the first self-governing country in the world in which all women had the right to vote in parliamentary elections.

In most other democracies – including Britain and the United States – women did not win the right to the vote until after the First World War. New Zealand’s world leadership in women’s suffrage became a central part of our image as a trail-blazing ‘social laboratory’.

That achievement was the result of years of effort by suffrage campaigners, led by Kate Sheppard. In 1891, 1892 and 1893 they compiled a series of massive petitions calling on Parliament to grant the vote to women. In recent years Sheppard’s contribution to New Zealand’s history has been acknowledged on the $10 note

Today, the idea that women could not or should not vote is completely foreign to New Zealanders. Following the 2014 election, 31% of our Members of Parliament were female, compared with 9% in 1981. In the early 21st century women have held each of the country’s key constitutional positions: prime minister, governor-general, speaker of the House of Representatives, attorney-general and chief justice

Three years after the vote was won in 1893, a convention of representatives of 11 women’s groups from throughout New Zealand resolved itself into the National Council of Women (NCW). Its aim was to ‘unite all organised Societies of Women for mutual counsel and co-operation, and in the attainment of justice and freedom for women, and for all that makes for the good of humanity’. More than a century later, the NCW still works in the interests of women, but it is a very different organisation from that established in the 1890s.

Suffrage milestones

1869 Mary Ann Müller (‘Femina’) wrote ‘An appeal to the men of New Zealand’, advocating votes for women.

1871 Mary Ann Colclough (‘Polly Plum’) gave her first public lecture on the rights of women, including their right to vote. Letters to and from ‘Polly Plum’ that appeared in the New Zealand Herald in 1871

1874 J.C. Andrew in the House of Representatives urged that women be enfranchised.

1878 Robert Stout unsuccessfully proposed in his Electoral Bill that women ratepayers be eligible to vote for and be elected as members of the House of Representatives.

1879 The government’s Qualification of Electors Bill was amended to give women property owners the vote, but parliamentarians who wanted all women to be enfranchised joined with those who opposed the reform to defeat the amendment.

1880 A Women’s Franchise Bill introduced by James Wallis lapsed after its first reading.

1881 Another Women’s Franchise Bill introduced by Wallis was withdrawn before its second reading.

1885 The New Zealand Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) was established following the visit of American temperance campaigner Mary Leavitt; by February 1886 there were 15 branches.

1886 At its first annual convention in Wellington, presided over by Anne Ward, the WCTU resolved to work for women’s suffrage.

1887 Two petitions requesting the franchise signed by some 350 women were presented to the House of Representatives. A Women’s Suffrage Bill to enfranchise women and give them the right to sit in Parliament was introduced by Julius Vogel but withdrawn at the committee stage.

1888 Two petitions asking for the enfranchisement of women signed by around 800 women were presented to the Legislative Council.

1889 The Tailoresses’ Union of New Zealand was established in Dunedin; many of its members, including the vice-president, Harriet Morison, were active in the suffrage campaign.

1890 A Women’s Franchise Bill introduced by Sir John Hall late in the parliamentary session lapsed, in spite of majority support, because there was no time to consider it. Hall then moved an amendment to the Electoral Bill to enfranchise women, but this was defeated.

1891 Eight petitions asking for the franchise signed by more than 9000 women were presented to the House of Representatives. A Female Suffrage Bill introduced by Hall received majority support in the House of Representatives but was narrowly defeated in the Legislative Council.

1892 The Women’s Franchise League was established first in Dunedin and later elsewhere. Six petitions asking for the franchise signed by more than 19,000 women were presented to the House of Representatives. The Electoral Bill, introduced by John Ballance, provided for the enfranchisement of all women. Controversy over an impractical postal vote amendment caused its abandonment.

1893 Thirteen petitions requesting that the franchise be conferred on women were signed by nearly 32,000 women, compiled and presented to the House of Representatives. Meri Te Tai Mangakāhia addressed the Māori parliament to ask that Māori women be allowed to vote for and become members of that body, but the matter lapsed. Read this address. A Women’s Suffrage Bill was introduced by Hall in June but withdrawn in October after it was superseded by the Electoral Act. An Electoral Bill containing provision for women’s suffrage was introduced by Richard Seddon in June. During debate, there was majority support for the enfranchisement of Māori as well as Pākehā women. The bill was passed by the Legislative Council on 8 September (after last-minute changes of allegiance) and consented to by the governor on 19 September. The Electoral Act 1893 gave all women in New Zealand the right to vote. On 29 November, the day after the general election, Elizabeth Yates was elected mayor of the borough of Onehunga – the first woman in the British Empire to hold such an office.

1919 The Women’s Parliamentary Rights Act gave women the right to stand for Parliament. Three women contested seats at the 1919 general election, but none were successful.

1933 The Labour Party’s Elizabeth McCombs became the first female Member of Parliament (MP), winning a by-election in the Lyttelton seat following the death of her husband, MP James McCombs. Number of women MPs in Parliament since 1933

1938 Labour’s Catherine Stewart became the second female MP after winning the Wellington West seat. She was defeated in the 1943 election.

1941 Women gained the right to sit in the Legislative Council, the nominated Upper House of Parliament. Labour’s Mary Dreaver joined Stewart in the House after winning a by-election in the Waitemata seat. She was defeated in 1943.

1942 Mary Grigg became the National Party’s first female MP. She won the Mid-Canterbury seat in a by-election after her husband, MP Arthur Grigg, was killed in action in North Africa.

1943 Labour’s Mabel Howard won a by-election in Christchurch East. She remained in Parliament until 1969.

1945 National’s Hilda Ross won a by-election in the Hamilton seat, which she held until her death in 1959.

1946 Mary Dreaver and Mary Anderson became the first women appointed to the Legislative Council. They both served until the council’s abolition in 1950.

1947 Labour MP Mabel Howard became New Zealand’s first female Cabinet minister. She served as minister of health and minister in charge of child welfare until Labour’s defeat in 1949, and then as minister of social security in the 1957–60 Labour government.

1949 Labour’s Iriaka Ratana became the first female Māori MP, succeeding her deceased husband, Matiu, in the Western Maori seat. The same year, Hilda Ross was appointed to the new National Cabinet.

1972 Whetu Tirikatene-Sullivan, Labour MP for Southern Maori, became the first female Māori Cabinet minister.

1996 At the first election held under New Zealand’s new mixed member proportional (MMP) system, 35 women MPs were elected, making up almost 30% of Parliament.

1997 Jenny Shipley became New Zealand’s first female prime minister after replacing Jim Bolger as leader of the National Party.

1999 Labour’s Helen Clark became New Zealand’s first elected female prime minister following the general election in November 1999. Clark would be PM for nine years, becoming New Zealand's 5th-longest-serving PM.

0 notes

Text

Hyperallergic: Remagining Monuments to Make Them Resonate Locally and Personally

Krzysztof Wodiczko. “Abraham Lincoln: War Veteran Projection” (2012) a project in Union Square, New York, NY sponsored by More Art (image courtesy of the artist)

This is not an act of vandalism. It is a work of public art and an act of applied art criticism. We have no intent to damage a mere statue. The true damage lies with patriarchy, white supremacy, and settler-colonialism embodied by the statue.

— October 2017 manifesto issued by the Monument Removal Brigade

Robert E. Lee never asked for them. Harvard-based public artist Krzysztof Wodiczko slyly proposes sending all of them to re-education camps. MRB imagines a day when they are “moldering away as a ruin in the trash-heap of history.” But the current and increasingly heated debate over how to represent our troubled, violently charged past (though hardly actually past) is merely the latest wave of an ongoing confrontation about whose history matters. The question that is still in need of an answer regarding the debate over public memorials that celebrate patriarchy, white supremacy, and settler-colonialism is not about what part of the nation’s past should be eliminated from view, but how we acknowledge the complex and often conflicted histories — good, bad, and ugly — that actually make up our collective experience. In truth, the current face-off is the culmination of several centuries in which the way history has been memorialized consistently reflected the interests of business leaders, municipal power brokers, wealthy arts patrons and to even main-stream academics. Significantly however, it also bears the marks of another, decades-old set of forces that includes socially engaged artists and community activists who have confronted, reinvented, and in some instances put into practice temporary interventions and performance works that challenge dominant forms of historical representation.

REPOhistory street sign by Susan Schuppli commemorating Brenda Berkman, New York’s first female firefighter, (1998) (image courtesy the author)

Opinions vary about what to do with these objects. They range from a desire to wipe the slate clean by removing all public memories of the Confederacy and white supremacy, to cloaking such monumental works beneath black tarp, much as the group Decolonize This Place — a coalition that includes Native American and Palestinian-rights activists — did last fall (October 14, 2016) with the Theodore Roosevelt monument outside the American Museum of Natural History. No, Roosevelt was not a Southern rebel; nevertheless, his equestrian statue is no less offensive. The 26th US President and former NYC Police Superintendent is depicted by artist James Earle Fraser with masculine vitality astride a horse. Head tilted back and eyes fixed on a distant horizon he wears his signature Rough Rider uniform from the Spanish American War. Flanking Roosevelt’s right side is an American Native chief, while on his left strides an African man in sandals and what appears to be a Maasai warrior’s Shuka robe. According to former Executive Director for the National Foundation for Advancement in the Arts, A. L. Freundlich, these accompanying figures are guides symbolizing Roosevelt’s “interest in the natural world.” According to Decolonize This Place, “New York’s premier scientific museum continues to honor the bogus racial classification that assigned colonized peoples to the domain of Nature, and Europeans to the realm of Culture,” adding that “a monument that appears to glorify racial hierarchies should be retired from public view.”

Still, there are other, equally engaging methods for confronting offensive historical monuments, such as marking the absence of public memorials to the 99% of us who have been forgotten or even erased from most urban spaces. These people include the laborers who built the city, the street urchins whose tears have soaked its pavements, and all generations of common people lacking the political or economic advantages of those who typically lay claim to management of our public memories.

Todd Ayoung, “Spirits of America” (1992) a REPOhistory temporary street sign from the counter-Columbus public installation that used a slot machine to “reinterpret the “sale” of Manhattan to the Dutch in 1626, contrasting European and Native American notions of land ownership, and linking this and other colonial “exchanges” to the ongoing controversy over gambling on the upstate Mohawk reservation (image courtesy of the author)

In 1992, five hundred years after Christopher Columbus came to the so-called new world and twenty five years before the current crisis of historical representation, a group of over thirty metal street signs with images and texts appeared in downtown Manhattan marking the forgotten, or often altogether unknown histories of working women, African Americans, Native peoples, Latinos and Asian Americans among other marginalized groups. The project was created by REPOhistory, a multi-ethnic group of artists, educators and activists whose mission was to “retrieve and relocate absent historical narratives at specific locations in the New York City.” With one-year permits from the Department of Transportation and support from the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council, the Municipal Art Society and the administration of Mayor David Dinkins, REPOhistory installed, and later de-installed, a suite of what we might call today “alt-historical” public markers attached to lampposts and traffic signs roughly between Chambers and Wall Streets.

REPOhistory street sign by Jenny Polak and David Thorne alerting New Yorkers to police violence against people of color from 1998.

One plaque marked the site of the first meal and slave market at the corner of Wall and Water Streets, another described what was then the very recent discovery of a “Negro Burial Ground” at the construction site for a new federal office building. Still others detailed the first all-women’s strike in the United States by the United Tailoresses Society near Church Street, the first Chinese American community in the city once located at the South Street Seaport, John Jacob Astor’s “problematic exchanges —commercial, ecological and spiritual” with Native Americans at his former headquarters on the north side of Pine between William and Pearl Streets, and still another temporary marker recalled the melting down of a gilded equestrian statue depicting King George III whose metal was molded into bullets later used during the War of Independence. Not all of the signs dwelt exclusively on the past. Outside the NY Stock Exchange REPOhistory installed a plaque that ironically cautioned passersby about the “advantages of an unregulated free-market economy.” It was illustrated with an image of a businessman in free-fall that recalled the Great Crash of 1929.

REPOhistory initially set its sights on creating a public intervention at “The Four Continents” by Daniel Chester French, a quartet of marble statues portraying allegories of Europe, Asia, Africa, and the Americas situated outside the former Alexander Hamilton US Custom House at One Bowling

Daniel Chester French “The Four Continents, Asia” dedicated 1907, marble (ranging from 9.5 to 11 feet), each pedestal about 9 feet; located in front of the United States Customs House, (photo by Eden, Janine and Jim via Flickr)

Green. Asia is presented as a bejeweled woman stoically siting atop a throne supported by human skulls and surrounded by near-naked, emaciated serfs. A glowing cross appears behind her back as if to indicate Christian values will soon replace Asia’s despotic past. Far to the left sits Africa. Though fabric drapes her waist she is characterized as a slumbering nude figure propped-up by an eroded Egyptian sphinx and a male lion. By contrast, Europe is illustrated as a stately, fully clothed woman next to a section of the Parthenon frieze, while America sits holding a torch and an ear of corn with her foot pressing down upon the head of Quetzalcoatl, the flying serpent god of the conquered Aztecs.

Despite being erected in 1907, “The Four Continents” reflects the derogatory racist outlook of 19th Century Manifest Destiny, just as the Roosevelt statue, dedicated in 1940, made its appearance while lynchings were being carried out across the Jim Crow South, and while Northern whites rioted to maintain racially segregated jobs and neighborhoods in Chicago, Detroit, and Los

Daniel Chester French “The Four Continents, Asia” dedicated 1907, marble (ranging from 9.5 to 11 feet), each pedestal about 9 feet; located in front of the United States Customs House, (photo by Eden, Janine and Jim via Flickr)

Angeles. Less known is the fact that African-American arctic explorer Matthew A. Henson, who is today recognized as having first reached the actual North Pole ahead of Admiral Robert Peary in 1909, later returned to the United States and worked the next thirty years as a customs house clerk. Whereas Peary was credited with the accomplishment, receiving international honors, an official Congressional thank you, and promoted to the rank of rear admiral, no marker or sign indicates Henson’s presence at Bowling Greene, though a modest plaque does mark his gravesite in Arlington Virginia.

In 1989, REPOhistory drew up plans to create inflatable “counter-monuments” that they would install illegally, in guerrilla art fashion, to confront this monument. Ultimately however, REPOhistory abandoned this interventionist historical adjustment to focus on their Lower Manhattan Sign Project scheduled for 1992. So what was the outcome of the counter-Columbus experiment in “people’s history”? It was mixed, unexpected, convoluted — just like the city that produced the project. Still, the point of REPOhistory was not nostalgia for a lost past, but rather an attempt to recognize that some histories disturb the present.

Several years later the group received Department of Transportation (DOT) permission to temporarily memorialize gay, lesbian, and trans-gendered people’s histories, this time in Greenwhich Village, with assistance from the Storefront for Art and Architecture. However, the project entitled “Queer Spaces” would be the last time that obtaining permission from the city would come easily for them. A third street sign project in 1998 was initially blocked by the Giuliani administration. “Civil Disturbances: Battles For Justice in New York City” was produced in partnership with New York Lawyers for the Public Interest. Its objective was to mark sites where significant legal confrontations led to the extension of civil rights for the politically and economically disfranchised. REPOhistory marked the firehouse at 250 Livingston Street in Brooklyn where Brenda Berkman worked after winning a lawsuit to become the city’s first female fire fighter, and one African-American group member who had been part of a de-segregation court case in New York posted her sign about the case outside the offices of the NAACP’s Legal Defense and Educational Fund on West 40th Street. Meanwhile, several other signs directly decried the NYPD’s history of misconduct and violence towards people of color. Carrying ladders and installation tools the DOT faxed a note informing REPOhistory it was not to carry out the project only moments before its commencement. “Now the signs may end up in the very courthouses that inspired them,” wrote David Gonzalez in the New York Times the next morning.

REPOhistory had its day in court and eventually prevailed, thanks to pro bono assistance from Debevoise & Plimpton. A few months delayed, the group’s “Civil Disturbances” sign project went up for one year, though not without further battles. All of this history may offer one answer to the question of what should replace monuments to racism and Confederate defection. Meanwhile, REPOhistory is not the only example of artists confronting the way the past is depicted.

Alan Michelson. “Earth’s Eye,” (1990) (courtesy of the artist)

In 1990, Mohawk artist Alan Michelson placed forty cast concrete markers near City Hall in Manhattan to indicate the location of Collect Pond, a large source of freshwater for the island’s indigenous population that is now completely paved over. In 2009 African American artist Dread Scott donned a sign with the phrase “I AM NOT A MAN” printed on it, replicating the iconic message placards carried by striking, black Memphis sanitation workers in 1968, except for the addition of the word not. Walking through the streets of Harlem, Scott’s social performance art provoked the largely African American passersby to consider all that has still to be accomplished since the Civil Rights Movement. Most recently an 1870 statue of Abraham Lincoln at the northern end of Union Square Park came to life, though not with the voice of the Republican emancipator, but through the faces and voices of fourteen recent war veterans who served in Afghanistan and Iraq. The 2012 reanimated monument was the work of artist Krzysztof Wodiczko.

Krzysztof Wodiczko. “Abraham Lincoln: War Veteran Projection” (2012) a project in Union Square, New York, NY sponsored by More Art (image courtesy of the artist)

Seeking to defend artworks that buttress racial, sexual, or class domination using the 19th century concept of “art for art’s sake” is not only distasteful, it is also without either historical or aesthetic merit. As Walter Benjamin once powerfully observed, “there is no document of civilization which is not at the same time a document of barbarism. And just as such a document is not free of barbarism, barbarism taints also the manner in which it was transmitted from one owner to another.” In this instance, memorials and statues reflecting undemocratic and biased points of view are these tainted historical documents. Instead of returning to a model of permanently memorializing an illusory and grandiloquent past, why not consider commissioning temporary commemorative works rooted in local community histories and struggles that would reflect the multifaceted history of the United States from the bottom up, rather than from the top down? In any case, the task of representing our nation’s complicated past at this, our (latest) moment of representational crisis, must not fall only to the inventiveness of artists, but needs to be seen as belonging to all engaged citizens, as well as residents, documented or not, who have a stake in reimagining the way history will be represented to future generations.

The post Remagining Monuments to Make Them Resonate Locally and Personally appeared first on Hyperallergic.

from Hyperallergic http://ift.tt/2izKomi

via IFTTT

0 notes