#vasubandhu

Note

What piece of art (book, music, movie, etc.) most influenced the person you are today?

I. A long prologue on the preconditions of an answer

Thanks for the great question: it's also a hard question to answer! (I've answered a similar question here, but this answer is quite different.) Already at the start, I have to avoid three traps in answering.

The first is including works I've been puzzled and fascinated by, but do not fully understand and so have not been sufficiently influential in the way I'm thinking of. (Examples: Jung and koans. I can talk about them with some plausibility, but do I really understand them? Being honest with myself, I don't.)

The second is including works which easily come to mind because I've enjoyed them, but which haven't been sufficiently influential either. (Lots of science fiction I've read fall under this category.) The third is making a list solely of classics, since I run the risk of making an uninformative list of what everyone already knows---or even worse, having classics simply because they are high-prestige. (Examples: the Epic of Gilgamesh, the Three Kingdoms.) Having said that, many classics have been genuinely influential in my life, and I'll mention some of them later. But I want to make sure that I include more than just classics.

Even while avoiding these traps, I find some difficulties in answering for two more reasons. First, because I haven't been influenced by any single piece of art in particular so much as I've been influenced by artistic works in general.

Second, because even more influential has been my general attitude towards art and culture (to go up a level) rather than any works of art in themselves.

To name some of these attitudes:

I think that the best way to experience artistic works is in their context, by seeing what they're reacting to and against; I think it's useful to see artistic works as part of a coherent tradition for that reason (and this is also why theory is useful).

I don't think you can get a pure experience of artworks, but that they're always shaped by (often invisible) interpretive lenses; I think the best art is transformative (a very Xunzian view); I think there are no compulsory works of art because of this. What transforms each person is different, just because each person is different.

One of my favourite quotes here is from Borges (quoted in the epilogue to Professor Borges; the original citation is to the 1979 interview Borges para millones):

I believe that the phrase “obligatory reading” is a contradiction in terms; reading should not be obligatory. Should we ever speak of “obligatory pleasure”? What for? Pleasure is not obligatory, pleasure is something we seek. Obligatory happiness! We seek happiness as well.

For twenty years, I have been a professor of English Literature in the School of Philosophy and Letters at the University of Buenos Aires, and I have always advised my students: If a book bores you, leave it; don’t read it because it is famous, don’t read it because it is modern, don’t read a book because it is old. If a book is tedious to you, leave it, even if that book is Paradise Lost—which is not tedious to me—or Don Quixote—which also is not tedious to me. But if a book is tedious to you, don’t read it; that book was not written for you.

Reading should be a form of happiness, so I would advise all possible readers of my last will and testament—which I do not plan to write—I would advise them to read a lot, and not to get intimidated by writers’ reputations, to continue to look for personal happiness, personal enjoyment. It is the only way to read.

II. Donald Richie's Japanese Portraits

Having given that very long disclaimer, if I had to select just one work which has been most influential to me and which isn't a well-known classic, it would be Donald Richie's Japanese Portraits. (If you'd like to read even more on this, @transientpetersen has reviewed it here and I've added some comments on its impact on me here.)

Richie's Japanese Portraits combines so much of what I like and has influenced my style (to the extent to which I have one) and taste: short vignettes with psychological insight, fragmentary pieces which add up to a greater whole even if there's never a unitary picture being painted. It led me to other similar authors (like Italo Calvino, Lydia Davis, Kurt Vonnegut, Sei Shōnagon and Yoshida Kenkō and the zuihitsu/xiaopin genre. . .)

And---most importantly---reading the book was one of the events in my life that taught me how to notice people, how to love them. (I can vividly remember a time when I was very bad at both, and it was only with great effort from those around me that I managed to learn to love. And, of course, the influence of the book pales in comparison to the influence of the people who loved me, loving people, lovely people. Love is both attention and action, and I'm still learning.)

Richie has a gift for encapsulating the universal in the particular. Reading the book made me a better person, and that's the highest compliment I can give any piece of art.

III. Other works

Having tried to pick a most influential work, I would be remiss not to mention the many others that have influenced me, often to the same extent. I'll name just a few which immediately come to mind rather than give a full list. Much like William H. Gass's list, I'd probably come up with a different list on a different day.

There isn't any visual art or music on the list---not because of their lack of worth (Philip Glass, Ryuichi Sakamoto, Nils Frahm, Ólafur Arnalds, Oasis, Mahler, and Shostakovich are all personally enjoyable and were influential at particular points!), but simply because I find it easier to cite, explain, and engage with texts, and so texts have been most influential for me. If you're interested, here's a bit on my musical tastes. Now, back to the list:

The Epic of Gilgamesh: Gilgamesh's faults are entirely human; it's a consoling book.

Sima Qian's Records of the Historian (read in the Yang and Yang translation): Ostensibly a book of history, but there's an entire ethos there of understanding the moments of rise and descent, of leaving when things are at their peak, of understanding the moment and waiting. I read it as a child and it was extremely influential in affecting how I behave up to now.

The Three Kingdoms (which I write about sometimes): I read this at around the same time as Sima Qian; the figure of Zhuge Liang exemplifies the tensions inherent when you try to combine the ethos of the Records with the actual prevailing situations.

Elizabeth Bishop's "One Art": There are so many times when I've reminded myself, "The art of losing isn't hard to master. . ."

Simon Leys's essay "The Chinese Attitude Towards the Past": It introduced an entirely new way of thinking about preserving history and memory to me.

Sociological theory, especially Weber, Durkheim, Goffman, and Foucault: They've all shaped my understanding of society and normality. I'm extremely sympathetic to the symbolic interactionists. Weber taught me to appreciate bureaucracy a little more, which has made me more patient while waiting on the telephone: now that's influential!

Key figures and texts within the various philosophical traditions: within the Chinese tradition, Xunzi and Dai Zhen; within the Indian tradition, the Dīgha Nikāya and Vasubandhu; within the Anglo-European tradition, Spinoza and Wittgenstein.

Gadamer's Truth and Method: I still don't fully understand it, but I was extremely influenced by his idea of the fusion of horizons. Some parts of it are pure poetry. When I read the passage where he says that nothing returns, I had a shiver down my spine.

Shen Fu's Six Records of a Floating Life: a depiction of love in a time very different from now, and all the more interesting and touching for that. My favourite passage is the part where Shen Fu and his wife Yün acknowledge the social pressures facing them, and talk about how they hope they can change positions in the next life to understand each other and to overcome these pressures:

Once I said to her, ‘It’s a pity that you are a woman and have to remain hidden away at home. If only you could become a man we could visit famous mountains and search out magnificent ruins. We could travel the whole world together. Wouldn’t that be wonderful?’

‘What is so difficult about that?’ Yün replied. ‘After my hair begins to turn white, although we could not go so far as to visit the Five Sacred Mountains, we could still visit places nearer by. We could probably go together to Hufu and Lingyen, and south to the West Lake and north to Ping Mountain.’

‘By the your hair begins to turn white, I’m afraid you will find it hard to walk,’ I told her.

‘Then if we can’t do it in this life, I hope we will do it in the next.’

‘In our next life I hope you will be born a man,’ I said. ‘I will be a woman, and we can be together again.’

‘That would be lovely,’ said Yün, ‘especially if we could still remember this life.’

There's so much encapsulated in this short passage: Shen Fu and Yün accept society's limitations while trying to transcend them within a framework they're familiar with, all while dwelling in the care and love and friendship between them. When I read this passage for the first time, I had to stop reading; I had started crying.

IV. On dealing with complexity

Most of the works which come to mind immediately are works of philosophy, theory, or nonfiction. This is no accident.

Life is complex, and there are at least two ways of dealing with the complexity of life. Philosophy tends to make it more explicit (although there are exceptions like Wittgenstein, where the very form of the Philosophical Investigations forces you to think in a particular way) and art tends to make it more implicit (although there are exceptions like programmatic music). In an interview, the philosopher David B. Wong recalls:

I remember taking a number of literature and mathematics courses, besides philosophy. Maybe philosophy combined the appeal of the other two fields for me—the clarity and systematic nature of mathematics and the focus on the human condition in literature.

I have a preference for the explicit, and so I prefer philosophy---but others with a different frame of mind may, for entirely valid reasons, prefer art.

For me, the one great advantage art has over philosophy is its greater pull on the emotions. Art helps build solidarity in a way philosophy doesn't (as Rorty points out). Philosophy does pull on the emotions: I've been happy or had shivers when reading philosophy, and sometimes I've been so excited that I had to get up and walk around before reading further. But I've never cried while reading philosophy, while I have cried before when reading literature.

Thanks for your question again!

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

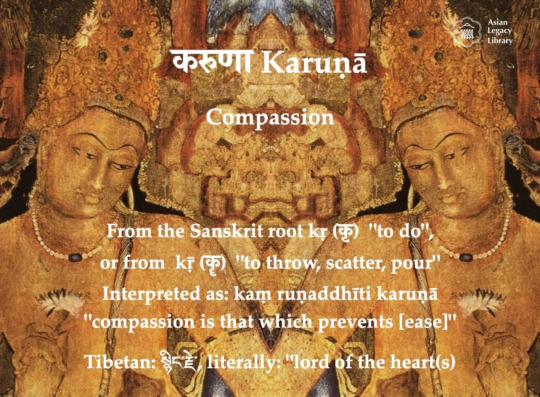

The Sanskrit term karunä, or compassion, is one of the fundamental mental states cultivated in order to achieve enlightenment.

Sthiramati's commentary to Vasubandhu's Pañcaskandha provides a canonical definition of compassion: it is, "the antidote to hurtfulness (vihimsäpratipaksah karuneti)," and, "that which prevents (kam runaddhiti karunā), the meaning being it prevents ease (sukham runaddhity arthah), for a compassionate being is uneased by the suffering of others (kãruniko hi para duhkhaduhkhi bhavatiti.)"

Compassion thus holds within it a quality of unbearable feeling for the suffering of others that precipitates action.

We cannot be at ease when we know there are other beings who are suffering. We must transform this unease into compassionate action for the benefit of others.

Mahäyana Buddhists identity mahäkaruna (great compassion) as the resolute conviction or an extraordinary intention to free others from suffering. It is a spontaneous, all-encompassing compassion towards all sentient beings, akin to the care of a parent for a beloved child.

#buddha#buddhism#buddhist#dharma#sangha#mahayana#zen#milarepa#tibetan buddhism#thich nhat hanh#padmasambhava#inner peace#four noble truths#tantric#green tara#Longchenpa#Guru Rinpoche#dalai láma#dhamma#Dzogchen#Bodhisattva#buddha samantabhadra

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

This teaching is not about denying that external reality exists. It is about understanding what and how we know for the purpose of helping us to cultivate and manifest the intention to alleviate suffering. Vasubandhu says the five senses arise like waves on the water of the root consciousness. A sailor who ignores the waves is going to be in deep trouble. It’s good to attend to the waves and engage in discernment. If you see charcoal clouds massing on the horizon and the wind is starting to whip up from the East, get inside, or get a raincoat. If you see a red flush forming on your colleague’s cheeks and her voice is rising in tone, volume, and pace, attend to what she is saying, how she feels, and your own emotions and thoughts arising. These waves are here in the moment and they are a part of what we are encouraged to attend to mindfully in these verses.

We are also encouraged to attend to the ocean, to the fact that the waves are part of a vast, unfolding interdependence, deeply manifesting our past conditioning by creating our present-moment way of seeing. If you see a coconut falling out of a tree toward your head, of course, there’s no need or time to direct your attention to the ocean—just get out of the way! However when you feel anxious or threatened at work or at home, it can be very helpful to remember that what you believe to be real, true sensory information about a threat is also a manifestation of your habits of seeing. This awareness—of the screen, the ocean, the storehouse—is here to help us lighten up a little bit, to soften, to have some compassion for ourselves, conditioned beings, to help us see the vast power our conditioning, and find compassion and openness about everything. This is a common thread in Buddhist teaching. Here we are encouraged to see that even at the very most raw and apparently “real” level of our experience—sight, sound, smell, taste, and touch—what we experience is deeply, karmically conditioned. Ultimately, we do not know what is.

- Ben Connelly, “Inside Vasubandhu’s Yogacra : A Practitioner’s Guide”

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

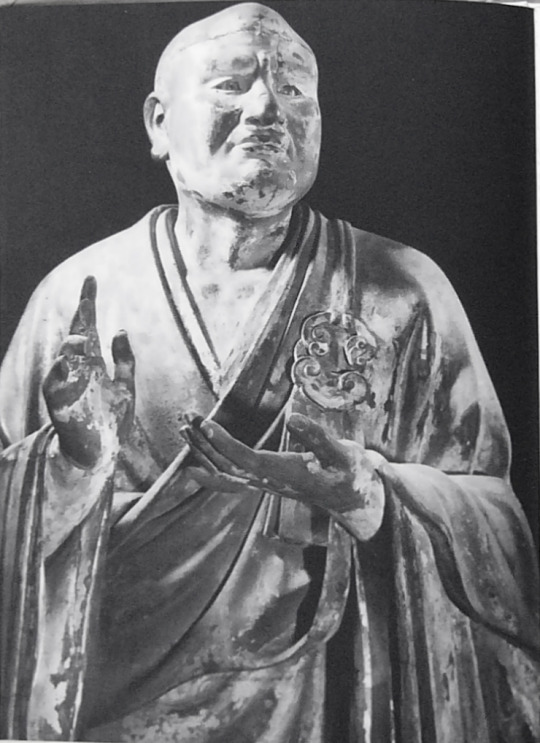

If not for the likes of Nagarjuna, Vasubandhu, T'an-luan, Daochuo, Shandao, Genshin, and Genkū from India, China, and Japan, Master Shinran would not have encountered the true teachings of Buddhism.

Just as a single break in a water pipe can prevent water from reaching its destination, if even one of these seven great masters had been missing, he would not have been saved. Therefore, he was deeply grateful for their teachings, and felt that he could never repay them enough.

—-More about BTH—-

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

VASUBANDHU

Fabricated, dependent and perfected: So the wise understand, in depth, the three natures. What appears is the dependent. How it appears is the fabricated. Because of being dependent on conditions. Because of being only fabrication. The eternal non-existence of the appearance as it is appears: That is known to be the perfected nature, because of being always the same. What appears there? The unreal fabrication. How does it appear? As a dual self. What is its non-existence? That by which the non-dual reality is there.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The universe does not originate from one single cause… things would arise all at the same time: but everyone sees that they arise successively" -Vasubandhu

I really need to say this, cause it really hurt. If I’m confiding about something that causes me dysphoria, a personal thing that causes a lot of serious mental anguish that makes me feel inadequate as a woman, suicidal, makes my heart feel like a collapsing star, but then when opening up about these feelings, I get told I’m a misogynist, not a real woman, etc because of my dysphoria and that my standards are based in white supremacy, it just hurts and makes me feel worse about my dysphoria. Just more alienated from womanhood. It happened another time before when we were talking, and it’s not about beauty standards so much as it’s about being seen as the gender I am. I’m just talking about a secondary sex characteristics that is rather ubiquitous to women despite race- not unlike breasts or not having a five o’clock shadow no matter how much I shave. I’m constantly stared at in confusion or disgust any time I go anywhere because as far as I can tell, I’m visually trans. I haven’t had any commiseration over this, I’ve gotten no positive reinforcement, the first time I was told I look different is when I showed my care taker old pictures of myself but I can see no difference despite that. Dysphoria and seemingly dysmorphic as well. Im not high femme, i don’t want to be Barbie or whatever the fuck. I’m treated as inadequate as a woman because I don’t have something, but wanting that thing also makes me inadequate as a woman. A catch-22. Nothing I can do is right. It does not make me feel safe. What do I call?

0 notes

Text

Buddha's doctrine is hard to find

Without it there is no liberation.

thus, aspiring for liberation,

One should devotedly listen to it.

~ Vasubandhu

佛陀的教義難遭遇

缺了它就沒有解脫

因此,渴望解脫者

應當專心致志聆聽

~ 世親菩薩

0 notes

Text

天親菩薩。世親(せしん、梵: Vasubandhu、蔵: dbyig gnyen)は、古代インド仏教瑜伽行唯識学派の僧である。世親はサンスクリット名である「ヴァスバンドゥ」の訳名であり、玄奘訳以降定着した。それより前には「天親」(てんじん)と訳されることが多い。「婆薮般豆」、「婆薮般頭」と音写することもある。

0 notes

Photo

"Underwater Airs" (In Tibetan astro science, two distinct flat-earth, stationary, geocentric cosmologies are recognized, both developed in India and later translated into Tibetan. The first is the Abhidharma system, expounded in the 4th or 5th century Indian text Abhidharmakosha (Treasury House of Knowledge) by Vasubandhu, and the Kalachakra system (Wheels of Time), whose root text was translated into Tibetan in 1027 A.D.. Both systems are mandala-like world systems made of concentric oceans and mountain ranges centered around an axis, Mount Meru. The known world exists on one of the four major continents (with other minor accompanying continents), the southern continent, called Jambudvipa. Mount Meru is lapis-blue on our side, which explains why it cannot be seen, but instead blends in with the sky's color.The heavenly bodies orbit around Mount Meru. The cosmic mandala pictured in the header above shows a bird's-eye view of Mount Meru and the orbits of the planets (including sun and moon).The world system, with its complex layered base, floats in space, and is only one of an immense number of such world systems, termed the trichilicosm (a number usually considered to be over a billion). The most obvious differences between the two cosmological systems are geographic and geometric, such as the shape of Mount Meru. Compare the pictures below for more details. To the Tibetans, the existence of two seemingly conflicting cosmological systems is not a problem, as neither is meant to be a complete representation of the universe as it is actually observed by scientists. As with all constructions such as mandalas and meditational deities, they serve different purposes and different audiences. For example, the Kalachakra cosmology is used philosophically to draw connections between cycles in the universe and those of human existence, and in an astronomical sense to develop a complex lunar calendar. Another central idea in Tibetan Buddhism is the concept that the Buddha taught many different kinds of texts and meditational systems because there is no "one size fits all...) https://web.ccsu.edu/astronomy/tibetan_cosmological_models.htm https://www.instagram.com/p/CeVWxXbJutF/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes

Text

Buda Amida, o Buda da Terra Pura da Suprema Bem-Aventurança, quando ainda era um Bodisatva chamado Dharmākara, disse em seu Voto Original:

"Quando eu me tornar um Buda, os seres nas Terras das Dez Direções, tendo a Mente Confiante com sinceridade, aspirando nascer na minha Terra e recitando o meu Nome mesmo que apenas dez vezes, nascerão na minha Terra Pura. Se houvesse o contrário, eu não atingiria a Iluminação Perfeita."

Buda Shakyamuni, o fundador do Budismo em nosso tempo e nosso mundo, disse:

"Se um bom homem ou uma boa mulher ouve a respeito do Buda Amida e mantém seu Nome seja por um dia, dois, três, quatro, cinco, seis ou sete dias, com a mente concentrada, sem se distrair, então, na hora da morte, o Buda Amida aparecerá com uma legião de seres veneráveis. Consequentemente, quando o tempo de vida chega ao fim, a mente desta pessoa não será acometida de um estado confuso e, imediatamente, nascerá na Terra da Suprema Bem-Aventurança do Buda Amida. Shariputra, percebendo estes benefícios, digo: todos os seres vivos que ouvirem este ensinamento devem aspirar ao Nascimento naquela Terra."

Mestre Nāgārjuna, 1° Patriarca da Terra Pura, disse:

"Todos os Bodisatvas disseram: quando estávamos no estágio inicial de Bodisatva, realizamos numerosas boas ações e várias práticas durante inumeráveis Kalpas. Todavia, os nossos apegos são demasiado difíceis de romper e o Samsara, demasiado difícil de esgotar. Praticando o Samadhi do Nembutsu (Recitação do Nome do Buda Amida, Namo Amida Butsu) podemos destruir nossos bloqueios karmicos e atingir a libertação."

Mestre Vasubandhu, 2° Patriarca da Terra Pura, disse:

"A Mente que aspira tornar-se um Buda é a mente que busca salvar todos os seres. A mente que busca salvar todos os seres é a Verdadeira Fé no Outro Poder (o poder de Amida). Fé é a Mente Una. A Mente Una é a Mente Adamantina. A Mente Adamantina é a Mente Bodhi. Esta é a Mente propiciada pelo Outro Poder. Logo após atingirmos a Terra (de Amida) criada pelo Voto (de salvar os seres que recitam seu Nome), realizamos o Supremo Nirvana. É então despertada em nós a Grande Compaixão, graças à virtude que nos vem de Amida.

Mestre Tan-Luan, 3° Patriarca da Terra Pura, disse:

"Nascer na Terra Pura da Suprema Bem-Aventurança do Buda é a senda última e o meio supremo para se tornar Buda. Por isso todos os Budas exortam-nos a atingirmos a Terra Pura. Considerando que são iguais todos os fenômenos, o Buda purificou seus atos físicos, verbais e mentais, para assim dissolver os três atos falsos dos seres vivos". "As palavras “até dez recitações” (do Nome) no Sutra indicam que o renascimento resultante na Terra da Suprema Bem-Aventurança já foi estabelecido".

Mestre Tao-Cho, 4° Patriarca da Terra Pura, disse:

"Paixões cegas e atos maus neste mundo corrupto assemelham-se a ventos furiosos e chuvas torrenciais. Os Budas, em sua compaixão, levam-nos a encontrar refúgio na Terra Pura. Mesmo que façamos o mal durante toda a nossa vida, se sempre repetirmos o Nembutsu com a mente sincera, seremos libertados, de forma espontânea, de todos os obstáculos para o Nascimento. Para conduzir e abraçar até mesmo os seres que façam o mal durante toda vida, ele jurou: Se aqueles que repetem o meu Nome não nascerem na Terra Pura, que eu não atinja a Iluminação."

Mestre Shan-Tao, 5° Patriarca da Terra Pura, disse:

"Se desejamos genuína e sinceramente renascer na Terra da Suprema Bem-Aventurança, devemos considerar tal desejo como realizado". "Mesmo depois da extinção dos Sutras, se as pessoas comuns encontrarem o Verdadeiro Ensinamento do Voto Original, revelado por Shakyamuni como o intento original de sua aparição no mundo, elas atingirão à Iluminação através do Nembutsu."

Mestre Genshin, 6° Patriarca da Terra Pura, disse:

"Para os homens carregados de graves males e erros, não há outro caminho. Dedicando-se a repetir o Nome de Amida (Namo Amida Butsu), eles nascerão na Terra Pura."

Mestre Hōnen, 7° Patriarca da Terra Pura, disse:

"Entre a expectativa de receber um presente e já tê-lo recebido de alguém, o que é melhor? Eu, Hōnen, recito o Nome do Buda com a compreensão de já ter recebido o presente do nascimento."

Mestre Shinran, o fundador do Shin Budismo da Terra Pura, disse:

"Quando confiamos que o Voto Inconcebível de Amida nos salva e assegura o nascimento na Terra Pura, surge em nosso coração o desejo de recitar o Nembutsu. Precisamos conscientizar-nos de que o Voto Original de Amida não faz distinção entre jovens e velhos, bons e maus. Só a Mente Confiante é essencial. Isso significa que o Voto tem por fim salvar aqueles a quem afligem profundos males cármicos e intensas paixões maléficas. Assim, ao confiarmos no Voto Original, não dependemos de outras práticas virtuosas porque não há bem superior ao Nembutsu, nem precisamos temer o mal, pois não há mal capaz de impedir o Voto Original de Amida."

Mestre Rennyo, o revitalizador do Shin Budismo da Terra Pura, disse:

"Quando recitarmos o Nome constantemente, andando, de pé, sentados ou deitados, que este Nembutsu seja sempre dito com a intenção de expressar nossa gratidão pela bondade do Tathāgata Amida. Tal atitude caracteriza o adepto que vivencia a verdadeira e autêntica Mente Confiante, alguém cujo nascimento está decididamente assegurado."

Assim, atendendo ao chamado do Buda e confiando em seus ensinamentos, recitemos o Namo Amida Butsu por toda a vida em profunda gratidão na confiança de sermos abraçados e jamais abandonados pelo Voto Original do Buda Amida que nos conduz a Terra Pura.

Namo Amida Butsu 🙏🏼

0 notes

Text

Duy biểu học – Hiểu sự vận hành của tâm

Thiền sư Thường Chiếu (thế kỷ thứ 12) đã nói “Khi ta hiểu rõ cách vận hành của Tâm thì sự tu tập trở nên dễ dàng”. Năm Mươi Bài Tụng Duy Biểu là cuốn sách về tâm lý và siêu hình học của Phật giáo, giúp cho chúng ta hiểu được sự hoạt động của Tâm (Citta), bằng cách hiểu được bản chất của các Thức (Vijñāna). Năm Mươi Bài Tụng Duy Biểu có thể được coi như một thứ bản đồ trên con đường tu tập.

Trong thiền quán, Bụt Thích Ca soi chiếu, hiểu rõ tâm Ngài một cách sâu xa. Từ hơn hai ngàn năm trăm năm nay, các đệ tử của Ngài học hỏi để biết cách chăm sóc tâm và thân họ, hầu có thể chuyển hóa những khổ đau để đạt tới an lạc.

Năm Mươi Bài Tụng Duy Biểu hình thành từ những dòng suối tuệ giác của đạo Bụt Ấn Độ, gồm các luận giảng A-tỳ-đạt-ma (Abhidharma – Thắng Nghĩa Pháp) trong tạng kinh Pali (1), tới giáo pháp Đại Thừa như Kinh Hoa Nghiêm (Avatamsaka Sutra). A-tỳ-đạt-ma là các luận giảng của đạo Bụt bộ phái, được hệ thống hóa từ giáo lý nguyên thủy.

Sự phát triển của triết lý Phật giáo thường được chia ra ba thời kỳ: Nguyên thủy, Bộ phái và Đại thừa (2). Năm mươi bài tụng Duy Biểu chứa đựng giáo pháp của cả ba thời kỳ đó.

Trong thời Bụt còn tại thế, Phật pháp là giáo pháp sinh động, nhưng sau khi Ngài nhập diệt, các đệ tử của Ngài có bổn phận hệ thống hóa những lời giảng của Ngài để có thể học hỏi cho thấu đáo hơn. A-tỳ-đạt-ma là một trong các tập hợp đầu tiên những bài giảng về tâm lý và triết lý, được nhiều đệ tử xuất sắc của Bụt khai triển trong nhiều thế kỷ tiếp theo.

Nguồn gốc 50 bài tụng Duy Biểu

Khi còn là chú tiểu, tôi được học thuộc lòng Nhị Thập Tụng và Tam Thập Tụng của Ngài Thế Thân, bằng tiếng Hán, do thầy Huyền Trang dịch. Khi sang Tây phương, tôi nhận ra rằng giáo pháp quan trọng về tâm lý của đạo Bụt có thể mở được cánh cửa hiểu biết cho người Âu Mỹ. Vậy nên năm 1990, tôi làm ra 50 bài tụng Duy Biểu để làm cho viên ngọc quý được sáng thêm. Đó là gia tài của Bụt, của Ngài Thế Thân, An Huệ, Huyền Trang, Pháp Tạng và nhiều vị khác nữa. Sau khi học 50 bài tụng, bạn sẽ hiểu được những bài cổ văn của các vị thầy lớn, và bạn sẽ hiểu được nền tảng của 50 bài tụng. Cuốn sách Duy Biểu Học cống hiến các bạn những phương pháp Nhìn sâu cách vận hành của tâm để có thể tự chuyển hoá được tâm thức của mình để sống an lạc, hạnh phúc hơn; và tiến tới trên con đường học đạo.

Năm mươi bài tụng để học Duy Biểu có vẻ mới, nhưng chỉ mới trên hình thức thôi. Về phương diện nội dung, chúng được làm bằng những yếu tố của Duy Biểu Học, bắt nguồn từ giáo lý Bụt dạy. Trong Kinh Pháp Cú, Bụt có nói Tâm là căn bản, Tâm là chủ các pháp. Trong Kinh Hoa Nghiêm Bụt dạy Tâm là họa sư có thể vẽ ra tất cả các hình ảnh. Cũng trong Kinh Hoa Nghiêm có một bài kệ mà các sư cô sư chú ở Việt Nam đọc mỗi ngày trong nghi thức cúng cô hồn: “Nhược nhân dục liễu tri tam thế nhất thiết Phật, ưng quán pháp giới tính, nhất thiết duy tâm tạo.” (Ai muốn hiểu được chư Bụt trong ba đời quá khứ, hiện tại và vị lai, phải quán chiếu bản tính của pháp giới và thấy rằng tất cả đều do tâm mình tạo ra). Hai chữ tâm tạo này phải được hiểu là tâm biểu hiện. Đó là căn bản của giáo lý Duy Thức mà ngày nay chúng ta gọi là Duy Biểu.

Tác phẩm “Duy biểu học – Nhìn sâu cách vận hành của tâm” này tuy được trình bày một cách mới mẻ nhưng trong nội dung thì dùng toàn những chất liệu cũ. Những chất liệu ấy được tìm thấy trong các tài liệu sau đây:

1/ Duy Thức Tam Thập Tụng của Thầy Thế Thân (Vasubandhu; 320 – 400)

2/ Tam Thập Tụng Chú Giải của Thầy An Huệ(Sthiramati 470-550)

3/ Thành Duy Thức Luận của Thầy Huyền Trang (Xuan Zhang; 600- 664)

4/ Nhiếp Đại Thừa Luận của Thầy Vô Trước (Asanga 321 – 390)

5/ Bát Thức Quy Củ Tụng của Thầy Huyền Trang

6/ Hoa Nghiêm Huyền Nghĩa của Thầy Pháp Tạng (494- 579).

Duy Thức Tam Thập Tụng của Thầy Thế Thân, được căn cứ trên bản tiếng Hán, tiếng Phạn và trên những lời bình giải của một nhà Duy Thức học nổi tiếng là thầy An Huệ.

Tam Thập Tụng Chú Giải của Thầy An Huệ bằng tiếng Phạn, được giáo sư Sylvain Lévi tìm ra ở Népal năm 1922 và đã được dịch ra tiếng Pháp và tiếng Quan Thoại (xuất bản năm 1925 – Đó là cuốn Materiaux pour l’etude du systeme Vijnaptimātra).

Thành Duy Thức Luận của Thầy Huyền Trang là bản dịch và chú giải Duy Thức Tam Thập Tụng của thầy Thế Thân. Tuy nhiên, lối dịch và chú giải của Thầy Huyền Trang rất đặc biệt. Thầy đã sử dụng tất cả tài liệu mà thầy học được từ đại học Nalanda (một đại học nổi tiếng của Phật giáo, phía Bắc Ấn Độ, nay là thị trấn Rajgir, tiểu bang Bihar), từ thế kỷ thứ 7 Tây lịch. Nơi đây Thầy Huyền Trang đã học với Thầy Giới Hiền và Thầy Hộ Pháp, là hai trong 10 vị luận sư nổi tiếng của Ấn Độ thời đó. Thầy Huyền Trang thu thập và đem về Trung Hoa những kiến thức của 10 vị luận sư này và thầy cho hết vào bản chú giải Thành Duy Thức Luận. Chúng tôi sử dụng bản Thành Duy Thức Luận bằng chữ Hán và bản tiếng Anh do một học giả người Hương Cảng dịch.

Nhiếp Đại Thừa Luận (Mahayana- samgrahashastra) của Thầy Vô Trước là một tác phẩm rất nổi tiếng. Nhiếp Đại Thừa Luận chứa đựng tất cả kinh nghĩa Đại thừa. Tư tưởng trong đó rất căn bản.

Khi học tác phẩm Duy Thức Tam Thập Tụng của Ngài Thế Thân, ta cứ nghĩ Ngài là tổ của Duy thức. Nhưng ta không biết rằng Ngài Vô Trước đã cô đọng tư tưởng Duy thức rất công phu trong Nhiếp Đại Thừa Luận.

Bát Thức Quy Củ Tụng của thầy Huyền Trang có thể xem là tác phẩm Duy thức mới, vì khi qua Ấn Độ, thầy Huyền Trang cũng được tiếp xúc với giáo lý của thầy Trần Na (Dignāna 400- 480), là người rất giỏi về luận lý học (logic) và nhận thức luận (epistemology). Vì vậy Bát Thức Quy Củ Tụng có màu sắc luận lý và nhận thức luận.

Hoa Nghiêm Huyền Nghĩa do Thầy Pháp Tạng sáng tác. Thầy chuyên về hệ thống Hoa Nghiêm. Thấy giáo lý Duy thức quan trọng và thầy muốn tuyệt đối đại thừa hóa Duy thức, đem giáo lý Hoa Nghiêm bổ túc cho Duy thức. Vậy nên trong Hoa Nghiêm Huyền Nghĩa, thầy Pháp Tạng đã đề nghị đưa tư tưởng “một là tất cả, tất cả là một” vào trong Duy thức. Nhưng tiếng gọi của Thầy Pháp Tạng không đem lại nhiều kết quả vì cả ngàn năm sau người ta vẫn tiếp tục học Duy thức của các thầy Thế Thân, Huyền Trang và Khuy Cơ như cũ.

Ước mong của tác giả

Sáng tác 50 Bài Tụng Duy Biểu, tác giả mong sẽ nối tiếp sự nghiệp của Thầy Pháp Tạng: đưa giáo lý Hoa Nghiêm vào Duy Biểu để cho Duy Biểu trở thành viên giáo.

Tác giả cố gắng trình bày tác phẩm này như một giáo lý Đại thừa.

Nếu trong khi đọc sách, bạn không hiểu một câu hay chữ nào đó, thì đừng cố gắng quá. Hãy để cho giáo pháp thấm dần vào bạn như khi bạn nghe nhạc, như mặt đất thấm những giọt nước mưa. Nếu chỉ dùng lý trí để học những bài tụng này, thì cũng giống như phủ lên mặt đất một tấm vải nhựa vậy. Nhưng khi bạn cho phép mưa pháp thấm sâu vào tâm thức, thì 50 bài tụng này sẽ cống hiến bạn tất cả giáo nghĩa của Thắng Pháp A-tỳ-đạt-ma.

Giáo pháp Duy Biểu là một môn học hết sức phức tạp và vi tế, chúng ta cần cả cuộc đời để tìm hiểu cho thấu đáo. Xin đừng nản lòng vì sự phức tạp đó. Hãy cứ học một cách từ tốn. Đừng đọc nhiều trang mỗi lần, mà chỉ đọc từng câu, cùng lời bình giải đầy đủ trước khi sang câu khác. Với chánh niệm và từ bi, bạn sẽ hiểu những bài học này một cách tự nhiên và dễ dàng.

Trong khi sáng tác Năm Mươi Bài Tụng Duy Biểu, tác giả nhắm đến tính cách thực dụng của giáo lý Duy Biểu. Tác giả mong rằng hành giả có thể sử dụng năm mươi bài tụng này vào sự tu tập hàng ngày. Trong quá khứ có nhiều người học Duy thức nhưng kiến thức về Duy thức của họ có tính cách lý thuyết và khó đem ra thực hành.

Tác giả đã từng gặp nhiều vị học Duy thức rất kỹ, nói về Duy thức rất lưu loát, nhưng khi được hỏi cái kiến thức đó có liên hệ gì tới đời sống hàng ngày hay không thì những vị đó chỉ mỉm cười không đáp. Trong khi đó, 50 Bài Tụng Duy Biểu trong sách này rất thực tế, có thể đem ra áp dụng trong mọi sinh hoạt của đời sống, hướng dẫn sự tu học, xây dựng tăng thân, chuyển hóa nội tâm và trị liệu khổ đau cũng như chữa trị những chứng bệnh tâm thần. Và như thế, có thể dùng làm căn bản trong các khóa tu dành cho các nhà tâm lý trị liệu Tây phương. Tác giả rất mong cuốn Duy Biểu Học – Nhìn sâu cách vận hành của tâm sẽ đóng được một vai trò trong lịch sử hành trì và chuyển hóa.

Thiền Sư Thích Nhất Hạnh

______________________________

Ghi chú

Kinh tạng: Các kinh điển và giới luật gồm thâu những lời Bụt Thích Ca giảng dạy và do các đệ tử học thuộc lòng rồi truyền lại cho nhau bằng cách tụng đọc hàng ngày. Kinh tạng cũng gọi là Tam Tạng Kinh điển (Tipitaka) gồm có :

Kinh (Sutta Pitaka): Kể lại các buổi thuyết giảng của Bụt.

Luật (Vinaya Pitaka): các giới luật Bụt chế tác cho các vị khất sĩ

Luận (Abhidhamma Pitaka): các bài giảng hệ thống hoá triết lý và tâm lý học Phật giáo

Kinh tạng Pali: được ghi trên lá kè (lá bối, thuộc loài Palm – Cọ) tại xứ Tích Lan (đảo Sri Lanka) khoảng 100 năm trước Tây lịch (hơn 300 năm sau khi Bụt nhập diệt).

Kinh tạng Hán văn: Cùng thời với tạng Pali (Nam truyền), tam tạng kinh điển cũng được ghi lại ở miền Bắc Ấn bằng tiếng Sanskrit, mà rất nhiều cuốn đã được dịch sang tiếng Hán (Hán tạng) và tiếng Tây Tạng – còn tồn tại tới ngày nay.

Các nước Phật giáo Á Đông đều có Tam tạng kinh điển bằng chữ Hán với phần trước tác của các thiền sư địa phương. Riêng nước Việt Nam, sau khi bị nhà Minh (Trung quốc) đô hộ, họ đã tiêu hủy hoặc tịch thu hầu hết các tác phẩm của thiền sư Việt Nam, kể cả Đại tạng kinh mà thời Lý – Trần đã để lại.

Ba thời kỳ của đạo Bụt:

Đạo Bụt Nguyên Thủy (Source, Original or Primitive Buddhism): do chính Bụt Thích Ca giảng dạy khi Ngài còn tại thế (từ giữa thế kỷ thứ 6 tới giữa thế kỷ thứ 5 trước Tây lịch).

Đạo Bụt Bộ Phái (Schools of Buddhist Sects) bắt đầu từ khoảng năm 340 trước Tây Lịch. Có chừng 20 bộ phái. Therevada nhận là phái nguyên thủy, thật ra đó là tiếp nối của phái Đồng Diệp Bộ (Tamrasatiya) thuộc Phân Biệt Thuyết Bộ (Vibhajyavāda)

Đạo Bụt Đại Thừa (Mahayana Buddhism): được hình thành rất sớm (thế kỷ thứ hai trước Tây lịch), có gốc rễ từ đạo Bụt nguyên thủy và thừa hưởng rất nhiều từ đạo Bụt bộ phái. Đạo Bụt Đại Thừa phát sinh do nhu cầu muốn đem giáo pháp thâm diệu của Bụt truyền bá cho đại chúng dưới một hình thức mới để họ có thể hiểu và hành trì được. Đạo Bụt Đại Thừa được phát triển từ khoảng 100 năm trước Tây lịch, nêu lên mẫu người lý tưởng là các vị Bồ tát, tu hành để giúp tất cả chúng sinh được giải thoát. Lý tưởng Bồ tát khác với lý tưởng A-La-Hán trong Tiểu Thừa, cho việc giải thoát cá nhân mới là quan trọng.

1 note

·

View note

Text

"Chi non è sveglio

non realizza l'inesistenza

dell'oggetto che vede in sogno."

(Vasubandhu)

#illusione

0 notes

Text

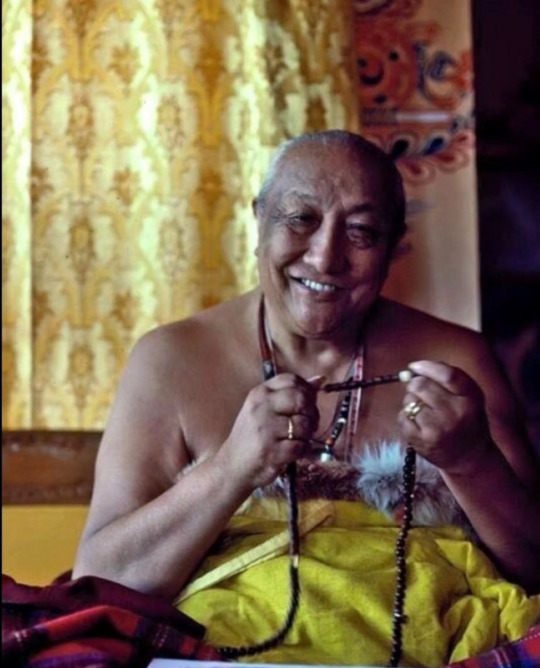

"Learning, reflecting and meditating are, in fact, the only things of which you can never have enough. Not even the most learned sages such as Vasubandhu, who knew nine hundred and ninety-nine important treatises by heart-ever thought they had reached the ultimate extent of learning, and were aware that there was still an ocean of knowledge to acquire. The bodhisattva Kumara Vasubhadra studied with one hundred and fifty spiritual masters, yet no-one ever heard him say that he had received enough teachings. Manjushri, sovereign of wisdom, who knows all that can be known, travels to all the buddhafields in the ten directions throughout the universe, ceaselessly requesting the buddhas to turn the Wheel of the Mahayana for the sake of beings. Be satisfied, therefore, with whatever you have by way of ordinary things - but never with the Dharma."

Kyabje Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche - The Heart of Compassion - Instructions on Ngulchu Thogme's Thirty-Sevenfold Practice of a Bodhisattva - pp 124-5, Padmakara Translation Group - Shechen Publications

#Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche#Padmasambhava#Guru Rinpoche#Longchenpa#four noble truths#amitaba buddha#manjushri#vajrasattva#vajrapani#Avalokiteshvara#buddha#buddhist#buddhism#dharma#sangha#mahayana#zen#milarepa#tibetan buddhism#thich nhat hanh#Dzogchen

6 notes

·

View notes

Note

fede neceisto tu ayuda! quiero arrancar a estudiar el Mūlamadhyamakakārikā¿me podrias recomendar una buena traduccion y algunos estudios complementarios que me puedan guiar en la lectura?

Hey, sí!

Consejo: no empezar por ahí de 0. Primero empezar por los Saravastivada y el Kosha de Vasubandhu. Luego, la versión de Vélez es muy buena. Simplemente, hay que estudiarla con alguien que se haya formado en la Madhyamaka

Espero que sirva!

F

0 notes

Photo

The Mind in Indian Philosophy II: Self and World

Last time, in Part I, we discussed how our minds represent things under the limiting conditions of sensibility. We began with the arguments of Kant on this topic; his philosophy of mind has many similarities with some much-older classical Indian philosophy.

Today we discuss some Indian philosophy of the self.

According to some philosophers, limitations of ourselves limit our knowledge of the external world. The basic idea is that if you change as a definite person—or if you never existed at all—the objects you perceive change as well because how you think, dream, and speak about objects is disunified.

For Arindam Chakrabarti (author of Realisms Interlinked; pictured), subjects and objects are intimately connected. A single ‘I’ of a mind must unify experiences over time to give nature to external reality (Nyāya-school arguments). A stable self achieves unification of objects by sustaining an objective time-order, carrying them in a coherent world in continued experience. So if a mind substantively changes and the single-self perspective dissipates, the objects housed in prior experience lose their structure.

Chakrabarti claims the mind can track the world because what is real about the world has the very nature of being knowable. Antirealists disagree and say this would render reality a product of the mind—a claim realists want to avoid! Sidestepping this challenge, Chakrabarti argues that subjects and objects must both be real for there to be real objects.

So are persisting subjects—selves—real?

Abhidharma Buddhist Vasubandhu claimed selves reduce to entities called ‘dhamas’. But these selves only hold ‘conventional’ existences. Pudgalavādins go further: they argue for the actual reality of persons. Nāgārjuna, in contrast, denied the existence of any fundamental object at all, including the self.

If there is no persistent self, there is no stable reality. As per Hume’s bundle theory, selves are just bundles of properties coming together. Objects, then, are bundles of properties coming together as well, appearing to us differently each time in representation under the limiting conditions of sensibility.

So here’s a scary thought.

Look at something you love, say, your pet. Ask: have you changed from five years or even 10 minutes ago? If you have, you better start firming up your reality; else you may have just lost a pet. The upshot is at least you gained a bundle of properties—and again; and again …

#philosophy#india#chakrabarti#vasubandhu#nagarjuna#buddhism#philosophy memes#indian philosophy#hume#mind#selves#reality#appearances#kant#cognition#intuition#subjects#objects#philosophyblr#philoblr

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

#thought provoking#inkstay#education#self development#fact#introspection#writerscommunity#strict parents#hostility#society#social justice#change#criminal justice#criminality#personality development#nonchalant#gyaat#gyaatverses#Vasubandhu#quotes#philosophy#psychotherapy#psychology#psychiatry#therapy#unconditionalselflove#unconditional acceptance#unconditional friendship#unconditionallove

8 notes

·

View notes