#vermilingua

Text

fun fact! anteaters belong to the suborder "vermilingua", which means “worm-tongue"

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Did you know, the mammal suborder Vermilingua (worm tongue), which is made up of the families Cyclopedidae and Myrmecophagidae are known to have destructive claws? Of course, you did. Did you know those claws can essentially break concrete? Common name: Anteaters, use such big destructive claws to destroy ant or termite mounds to retrieve their next meal.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Animal practice 10

Mammals 2

Xenarthra

Cingulata

Ancil (Banded Armadillo)

Rosado (Fairy armadillo)

Folivora

Duo (Two toed Sloth)

Trio (Three toed Sloth)

Vermilingua

Fabric (silky anteater/tamandua)

Alvin ( Giant anteater)

#the watchful eye#watchful eye#my ocs#my oc#my art#isle 0#toonverse oc#elementalgod aj#aj the elementalgod#o'kong family#neo demons#earthdemons#anthro allies#armadillo#sloths#anteaters#mammals

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

I (4M) am a l long-nosed mammal in the suborder vermilingua with no teeth and a long, sticky tongue suited to catching tunneling insects AITA??

1 note

·

View note

Video

youtube

Oso hormiguero en Drake Corcovado en Costa Rica (Vermilingua)

0 notes

Photo

Silky anteater (Cyclopes sp.)

Photo by Paula Senra

#unidentifiable#silky anteater#pygmy anteater#cyclopes#cyclopedidae#vermilingua#pilosa#xenarthra#atlantogenata#eutheria#mammalia#tetrapoda#vertebrata#chordata

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

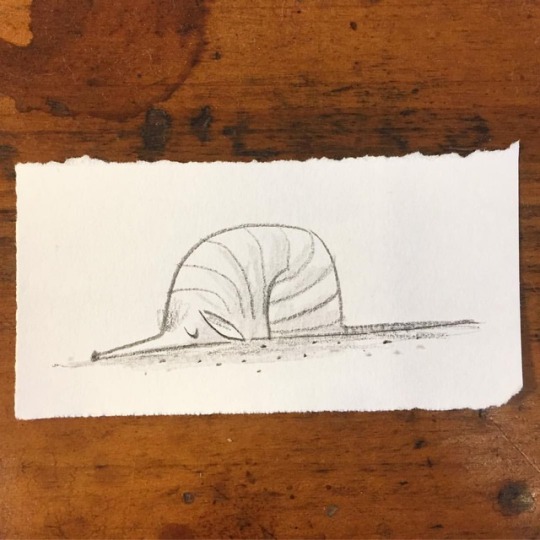

Also an anteater request from kofi!

Kofi link

#art#animal art#artists on tumblr#anteater#giant anteater#mammal#vermilingua#biology#zoology#i dunno fjsgdjshhr#kofi#snart

239 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ikonom Torgul and Digsburr, the Armored Vermilingua

#fantroll#fantrolls#homestuck#hiveswap#sharklilly's fantrolls#ikonom torgul#lusus#lusus naturae#Haphazard

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Worm tongue

Vermilingua

From Latin vermis (”worm”) + lingua (”tongue”).

Vermilingua is the suborder of mammals that contains the anteaters.

image credit: Ellen from Ann Arbor, MI, USA [CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)]

66 notes

·

View notes

Note

"since everything's a little weird right now & most seem to be bored I thought we could play a quarantine game 💘 answer the following! 1. how has your day been? 2. what is the last thing that made you smile? 3. what's keeping you entertained these days? 4. if you are in some kind of quarantine/self isolation: is there anything you'd like to archieve in this time? 5. post a selfie! (if you're comfortable with that) 6. last but not least: send this to some mutuals to keep the game going 🥰"

hiiii🌻

1 - how has your day been?

so far it’s been really good! a little bit tired of writing this research paper and i haven’t been getting much sleep though but that’s just the basics

2 - what is the last thing that made you smile

that the vermilingua can’t get the virus because it’s full of anty-bodies (all credits go to jess and her stroke of genius)

3 - what’s keeping you entertained these days

when im not working,,, it’s probably animal crossing

4 - is there something you’d like to achieve in this time?

i’d like to pick up reading again, which i haven’t done in a while since school’s been keeping me really busy:/

5 - post a selfie

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

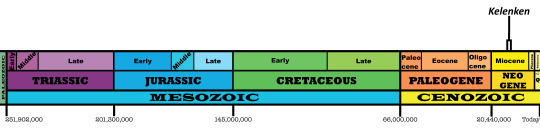

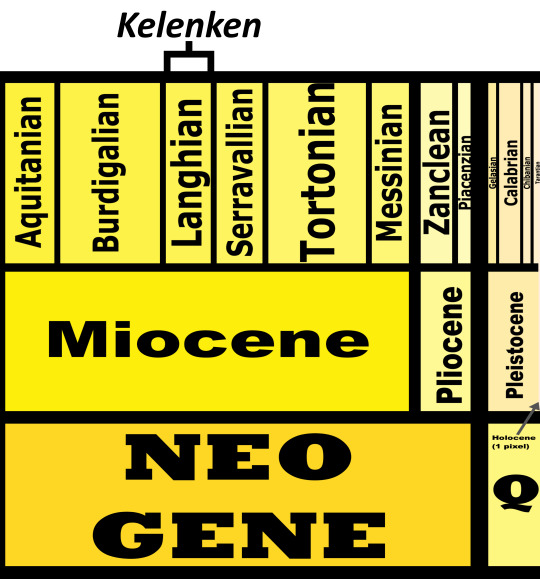

Kelenken guillermoi

By Scott Reid

Etymology: For Kélenken, the Bird of Prey Spirit of the Tehuelche Tribe

First Described By: Bertelli et al., 2007

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostaylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Neoaves, Inopinaves, Telluraves, Australaves, Cariamiformes, Phorusrhacoidea, Phorusrhacidae, Phorusrhacinae

Status: Extinct

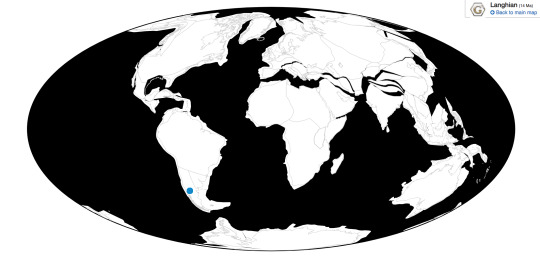

Time and Place: Between 15.5 and 13.8 million years ago, in the Langhian age of the Miocene of the Neogene

Kelenken is known from the Collón Curá Formation of Rio Negro Province, Argentina

Physical Description: Kelenken was a Terror Bird, a type of large flightless terrestrial dinosaur from the late Cenozoic era, mostly in South America though a few reached North America when the continents collided. These were some of the top predators of their environments, built for chasing down food over long distances and then using their monstrous beaks to tear into flesh. Kelenken was one of the biggest members of the group, about two meters tall, and it had one of the largest known skulls of any bird, with fused bones to give it significant strength in its head and strong bire force. Its limbs were very robust, probably allowing for powerful movements of the legs. It had very small wings, as other Terror Birds did, and as such they probably weren’t used very much (think of the arms of Carnotaurus but the bird version). It had a long, winding neck, and its head was mostly beak. The beak was hooked at one end. It had a short tail, though we don’t have any feather impressions to know if it had any sort of feather decoration at the end of it. It would have had a huge bite force, and it possibly was a faster runner than other Terror Birds.

Diet: Kelenken primarily fed on large animals, especially faster moving ones such as hoofed mammals

Behavior: Kelenken probably spent most of its time chasing down its prey, though it’s uncertain how. It’s possible that it would chase down prey, catch it, and shatter its bones with its beak by repeatedly pecking at it (if… pecking is an accurate word to use with such a huge beak doing the pecking). It’s also possible that it would chase down smaller prey, pick it up, and shake it vigorously to break the prey’s back. It also possibly scavenged off of prey. Honestly, it seems likely that Kelenken would utilize all these strategies, and those not even come up with, to get any prey it could in an opportunistic fashion.

By Michael B. H.

Kelenken was a fairly fast animal, and probably able to run for longer distances. As its environment was transitioning to an open grassland rather than a forest, this ability to run moreso than its earlier relatives was probably a direct adaptation for that open habitat. As such, Kelenken would have been extremely alert and on the lookout, both for food and for potential dangers, as it was tall enough to poke out above the grass and be visible to anything looking for it. Kelenken could fight with others of its species and against other animals both with its beak and with its feet, as it had very robust legs that would have been good for kicking, possibly very rapid and sharp kicks.

As only a few specimens of Kelenken are known, it’s difficult to determine its social behavior, especially since its closest living relatives are the Seriemas - a much smaller sort of dinosaur. Still, it’s possible to at least glean some behavioral patterns from seriemas. It’s possible that, like living seriemas, Kelenken only spent its time in pairs and small groups, which may have worked together cooperatively to take down larger mammalian sources of prey. It’s also possible that it may have been territorial over its nests, with breeding pairs avoiding other Kelenken and fighting with those they come across. This is all speculative, but would make sense given the environment and size of the animals. Kelenken, being a bird, almost decidedly took care of its young, though we cannot know if both parents took care of the young as in modern Seriemas, or if only one parent did the job at a time as in modern flightless birds. More fossils might be able to clear up this picture, though of course, it’s possible we’ll never know.

By Ripley Cook

Ecosystem: Kelenken lived in the part of the Miocene that was the hottest, called the Middle Miocene Climatic Optimum. This was immediately followed by drastic cooling. Thus, Kelenken lived in a uniquely warm period of the time in which Terror Birds dwelled. The formation was surrounded by extensive rivers and lakes, as basins formed in South America due to tectonic plates separating. This environment was a growing grassland, with the pampa overtaking the old deciduous forest that had once been there.

Kelenken is the only dinosaur known from the formation, but there were many different types of mammals present. There were the heavy-bodied hoofed mammals Protypotherium, Epipatriarchus, and Interatherium; the smaller hoofed mammals Hegetotherium and Pachyrukhos; the weird fast hoofed mammal related to Macrauchenia, Theosodon; armadillo relatives such as Proeutataus, Paraeucinepeltus, Peltephilus, Prozaedyus, and Stenotatus; the anteater relative Neotamandua; the rodents Galileomys, Guiomys, Maruchito, Microcardiodon, Neosteiromys, Protacaremys, Acarechimys, Alloiomys, Megastus, Neoreomys, Prolagostomus, and Stichomys; the new-world monkey Proteropithecia; the sabre-toothed marsupial Patagosmilus; and the extinct shrew opossum relative Abderites. There were also reptiles such as boa relatives like Waincophis, lizards, and turtles like Chelonoidis. There was also the horned frog Wawelia.

Kelenken probably would have hunted a variety of these things, especially the hoofed mammals, though some would have been too big for it to eat. It definitely would have been in direct competition with Patagosmilus, which probably would have specialized on different prey than Kelenken.

Other: Kelenken is most closely related to phorusrhacids such as Phorusrhacos and Titanis, two of the other more famous genera in this group.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources under the Cut

Abello, María Alejandra, and David Rubilar Rogers. 2012. Revisión del género Abderites Ameghino, 1887 (Marsupialia, Paucituberculata). Ameghiniana 49. 164–184. Accessed 2019-02-15.

Albino, A.M. 1996. Snakes from the Miocene of Patagonia (Argentina) Part I: The Booidea. Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie, Abhandlungen 199. 417–434. Accessed 2019-02-27.

Angolin, F. L., P. Chafrat. 2015. New fossil bird remains from the Chinchinales Formation (Early Miocene) of Northern Patagonia, Argentina. Annales de Paleontologie 101: 87 - 94.

Baez, A. M., S. Peri. 1990. Revision de Wawelia gerholdi, un anuro del Mioceno de Patagonia. Ameghiniana 27(3-4):379-386

Bertelli, S., L. M. Chiappe, C. Tambussi. 2007. A new phorusrhacid (Aves: Cariamae) from the middle Miocene of Patagonia, Argentina. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 27(2): 409 - 419.

Bondesio, P.; J. Rabassa; R. Pascual; M.G. Vucetich, and G.J. Scillato Yané. 1980. La formación Collón-Curá de Pilcaniyeú Viejo y sus alrededores (Río Negro, República Argentina) su antiguedad y las condiciones ambientales según su distribución su litogenesis y sus vertebrados. Actas del Segundo Congreso Argentino de Paleontología y Bioestratigrafía y Primer Congreso Latinoamericano de Paleontología 3. 85–99.

De Broin, F., and M. De la Fuente. 1993. Les tortues fossiles d'Argentine: synthese (The fossil turtles of Argentina: synthesis). Annales de Paléontologie (Invertebrés-Vertebrés) 79. 169–232. Accessed 2019-02-27.

Forasiepi, A.M., and A.A. Carlini. 2010. A new thylacosmilid (Mammalia, Metatheria, Sparassodonta) from the Miocene of Patagonia, Argentina. Zootaxa 2552. 55–68. Accessed 2019-02-27.

Gonzaga, L. P., A. Bonan. 2017. Seriemas (Cariamidae). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

González Ruiz, Laureano Raúl; Flavio Góis; Martín Ricardo Ciancio, and Gustavo Juan Scillato Yané. 2013. Los Peltephilidae (Mammalia, Xenarthra) de la Formación Collón Curá (Colloncurense, Mioceno Medio), Argentina. Revista Brasileira de Paleontologia 16. 319–330. Accessed 2019-02-27.

González Ruiz, Laureano Raúl; Alfredo Eduardo Zurita; Gustavo Juan Scillato Yané; Martín Zamorano, and Marcelo Fabián Tejedor. 2011. Un nuevo Glyptodontidae (Mammalia, Xenarthra, Cingulata) del Mioceno de Patagonia (Argentina) y comentarios acerca de la sistemática de los gliptodontes "friasenses". Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Geológicas 28. 566–579. Accessed 2019-02-27.

Kay, R.F.; D. Johnson, and J. Meldrum. 1998. A new Pitheciin Primate from the Middle Miocene. American Journal of Primatology 45. 317–336. Accessed 2019-02-27.

Kramarz, Alejandro; Alberto Garrido; Analía Forasiepi; Mariano Bond, and Claudia Tambussi. 2005. Estratigrafia y vertebrados (Aves y Mammalia) de la Formación Cerro Bandera, Mioceno Temprano de la Provincia del Neuquén, Argentina. Revista Geológica de Chile 32. 273–291. Accessed 2017-10-20.

McDonald, H.G.; S.F. Vizcaíno, and M.S. Bargo. 2008. Skeletal anatomy and the fossil history of the Vermilingua, 64–78. S. F. Vizcaíno, W. J. Loughry (eds.), The Biology of the Xenarthra. Accessed 2019-02-27.

Náñez, Carolina, and Norberto Malumián. 2019. Foraminíferos miocenos en la cuenca Neuquina, Argentina: implicancias estratigráficas y paleoambientales. Andean Geology 46. 183–210. Accessed 2019-02-27.

Oriozabala, C.; J. Sterli, and L. González Ruiz. 2018. Morphology of the mid-sized tortoises (Testudines: Testudinidae) from the Middle Miocene of Northwestern Chubut. Ameghiniana 55. 30–54. Accessed 2019-02-27.

Pardiñas, U.F.J. 1991. Primer registro de primates y otros vertebrados para la Formacion Collón Curá (Mioceno medio) del Neuquén, Argentina (First record of primates and other vertebrates from the Collón Curá Formation (middle Miocene) of Neuquén, Argentina). Ameghiniana 28. 197–199. Accessed 2019-02-27.

Pearson, Paul N., and Martin R. Palmer. 2000. Atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations over the past 60 million years. Nature 406. 695–699. Accessed 2019-02-27.

Pérez, M.E., and M.G. Vucetich. 2011. A new Extinct Genus of Cavioidea (Rodentia, Hystricognathi) from the Miocene of Patagonia (Argentina) and the Evolution of Cavoid Mandibular Morphology. Journal of Mammalian Evolution 18. 163–183. Accessed 2019-02-27.

Pérez, M.E.. 2010. A new rodent (Cavioidea, Hystricognathi) from the middle Miocene of Patagonia, mandibular homologies, and the origin of the crown group Cavioidea sensu stricto. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 30. 1848–1859. Accessed 2019-02-27.

Rehr, D. 2007. Prehistoric Predators - Terror Bird. 5:40 - 11:40. National Geographic.

Silvestro, Daniele; Marcelo F. Tejedor; Martha L. Serrano Serrano; Oriane Loiseau; Victor Rossier; Jonathan Rolland; Alexander Zizka; Alexandre Antonelli, and Nicolas Salamin. 2017. Evolutionary history of New World monkeys revealed by molecular and fossil data. BioRxiv _. 1–32. Accessed 2017-09-24.

Tambussi, C. P. 2011. Palaeoenvironmental and faunal inferences based on the avian fossil record of Patagonia and Pampa: what works and what does not. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 103: 458 - 474.

Vera Nardoni, Bárbara; Marcelo Reguero, and Laureano González Ruiz. 2017. The Interatheriinae notoungulates from the middle Miocene Collón Curá Formation in Argentina. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 62. 845–863. Accessed 2019-02-27.

Vucetich, M.G., and A.G. Kramarz. 2003. New Miocene rodents from Patagonia (Argentina) and their bearing on the early radiation of the Octodontoids (Hystricognathi). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 23. 435–444. Accessed 2019-02-27.

Vucetich, M.G.; M.M. Mazzoni, and U.F.J. Pardiñas. 1993. Los roedores de la Formación Collón Curá (Mioceno Medio), y la ignimbrita Pilcaniyeú, Cañadón del Tordillo, Neuquén. Ameghiniana 30. 361–381. Accessed 2019-02-27.

#kelenken#kelenken guillermoi#terror bird#bird#dinosaur#birds#dinosaurs#birblr#palaeoblr#neogene#south america#carnivore#terrestrial tuesday#australavian#paleontology#prehistory#prehistoric life#factfile#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature

311 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Anteater

Vermilingua

Source: Here

169 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Giant anteater (Myrmecophaga tridactyla)

Photo by Andreas Volz

#giant anteater#myrmecophaga tridactyla#myrmecophaga#myrmecophagidae#vermilingua#pilosa#xenarthra#atlantogenata#eutheria#mammalia#tetrapoda#vertebrata#chordata

82 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Any Dreaming 🖤Lunchbox Love🖤 #Vermilingua #Anteater #illustration #kidlitart #doodle #2minutedoodles #LunchboxLove

0 notes