#we love lya in this household

Text

Imagine Taylor Swift’s songs (VIII): You Belong With Me.

Imagine you fall in love with your neighbor, who happens to be your childhood best friend, unaware that he bears now a bad reputation and is Alys Rivers’s boyfriend.

Warnings: none; fluff and drama; silly, light reading to start our 2024 well and relaxed. :p

***

You are just going back from college. These are trying days, when you are about to enter your last semester before finally closing the course y/c. Not to mention the internship and tons of final paperworks expected to be done in what should be your vacations.

Such are your thoughts as you go back home. You share your household with your cousin named Lya Baratheon at King’s Landing in a nice neighborhood. But when you arrive at last after two hours traveling by bus, you are welcomed by Aemond Targaryen, your childhood friend who happens to have moved next to you.

“Hello, there!”, Aemond smiles at you.

You promptly leave your backpack down at the garden of your house before running to him before being fully embraced by his strong arms.

“Aemond!”, you hold on tight. “Long time no see! I missed you!”

As he places you down eventually, Aemond sees the woman you’ve become: your y/c hair is tied in a ponytail, there’s also a sweet bangs over your eyebrows. Your face has softened in delicate features and this time there’s a red lipstick painting your lips.

Although you dress casually, Aemond’s eyes can tell you’ve got bigger boobs last time he saw you—and that was 15 years ago, when you were both 12 years old.—, which earns him a smirk.

“Looking beautiful as I remember, Y/N”, he is pleased when seeing you blush.

Some things never change.

“Oh please”, you giggle softly. “So you are my neighbor now, eh? What a coincidence.”

“Yeah, indeed it is. I didn’t know you were living here. My mother recommended this neighborhood after I refused sharing a household with Aegon.”

“Oh. Are you two still not getting along?”

Aemond puts his hands on his pocket jeans and laughs.

“We always got along, but we have been following different roads now. I’ll tell you about it later. Are you coming home from a travel or something?”

“I entered college later than my fellow classmates”, you tell him. “I wanted to work a bit before getting into this academic world. So I’m still about to close it.”

“And what are you studying?”, Aemond inquires, interested in your independent spirit.

As you tell him about your college course, you notice how handsome he’s become. Taller, indeed, but stronger and with eyes so full of life. Your heart flutters foolishly, especially when you remember the old days where you two were so attached that Mrs Alicent used to joke about the day you’d get married.

“Do you want to come inside?”, you invite him after a few more minutes catching up.

“I wish I could, but I’m waiting for my girlfriend”, Aemond hates to break the joy of this reunion, even more so when your smile falters lightly, but he had to be honest with you.

“Of course”, you try not to look so disconcerted. And why, oh why, would I? “Even so you can bring her too if you like.”

Aemond ponders it, aware of your good intentions, but probably more conscious that you know nothing about his past and who his girlfriend is.

“Thanks, Y/N. I’ll see you around, though.”

As you turn your back to go inside your home, you miss Aemond’s sad gaze following you. Your absence soon leaves a hole where he thought an old wound was closed for good…

***

You're on the phone with your girlfriend, she's upset. She's going off about something that you said. 'Cause she doesn't get your humor like I do…

The next day you leave your bed earlier, trying to distract your head you opt to have some running outside. The morning is inviting and you need to get yourself some exercises before starting your college’s stuff.

After having breakfast and dressing, you pick your headphones and phone, all ready to go when you open the door and spot a very angry Aemond outside, sitting in the sidewalk as he speaks on the phone.

You sigh, probably wondering the cause. It’s either his family or his girlfriend. You carefully approach him, not letting be noticed until he turns off the phone.

“Fuck!”, he curses, before spotting you at last. “By the Maker! Sorry, Y/N, didn’t see you here.”

“No worries. I didn’t mean to intrude, but you looked upset and I came here to check on you.”

As Aemond stares at you almost in disbelief, he remembers how often as children he protected you of the bullies at school, and how you did the same whenever he misbehaved—often excusing his behavior before his own parents.

“We…just had a fight, is all”, he shrugs his shoulders.

“Do you want to talk about it?”, you ask him gently, sitting next to him.

“Not really, no.”

But he eventually does. You don’t know the woman’s name, but come to find out she is temperamental and willful, at times difficult to deal with.

For the first time in a while, Aemond feels heard. You are there for him, not a mere physical presence—and here he cannot help a comparison with Alys. At times he wonders how the hell he got so lost.

Towards the end of it, he is surprised by your embrace.

“I thought you might need it”, you explain before the disconcert look stamped in his face, which reminds you how often you used to climb his back as children and he’d awkwardly take you around his household.

The same idea runs in the back of his mind, making Aemond smile in nostalgia.

“Always the optimistic. You haven’t changed a bit, Y/N.”

A laughter echoes the air as you two share a look.

***

I'm in the room, it's a typical Tuesday night. I'm listening to the kind of music she doesn't like. And she'll never know your story like I do…

You have finished your final assignments after all. Considering preparing something to eat, you do miss having a company. Your cousin is away, so this leaves you with your neighbor, who happens to be your childhood best friend.

It’s when you open the window that gives you sight to his house and scream out his name.

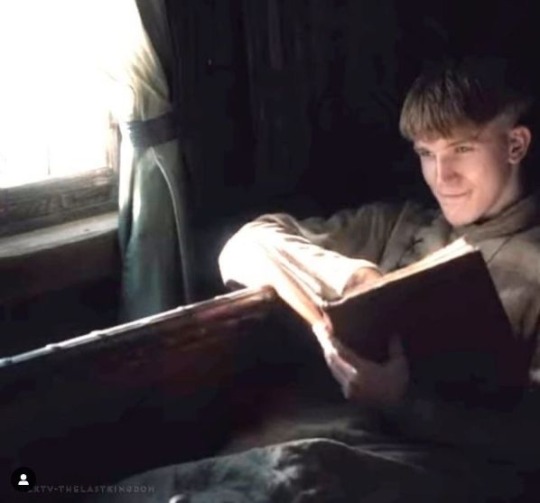

Aemond, who’s been busy reading a book, chuckles quietly when hearing you calling him a note above the heavy metal sound he’s been listening.

“Hey, girl”, he leans over the window. “What’s up? Listening to rock’n’roll today? I always figured you’d prefer classical music.”

You pull a grimace.

“What do you know of my musical tastes, Aemond Targaryen?”

He laughs quietly. It’s been a while since someone made him laugh like this.

“Well, hit me, baby. What do you want for me?”

“Have you dinned yet?”

“Nope. You?”

“I was about to cook some hamburgers. Do you want any?”

Aemond side smirks at you.

“I’ll be there in five.”

*

And here he is, eating with you late Tuesday night. Aemond soon knows about your college short break, how you are preparing for your last semester and your expectations for your graduation.

“Enough about me”, you say as you open two beers. “What have you been up to?”

“I have nothing interesting to say”, he shrugs his shoulders.

In truth, he is not willing to share the dark path he’s taken. Involved with the gang of his Hightower cousins, coercing those who owe Gerold some money, and doing other business on behalf of Aegon, he now believes to be a loser when compared to you.

“I doubt that”, you poke him. “Come now… What has your father forced you to do now?”

Mr Viserys is the main man behind the Targaryen Org., an advocacy office that has been working in politics behind the scenes and that has produced a few presidents of Westeros, the most recent of them being his daughter, Rhaenyra.

He expects his children to follow the same path, and that is why he and his sons—Aemond and Aegon, particularly—never really enjoyed a good and stable relationship. To worse it all, Mrs Alicent, his second wife, is facing a crisis in their marriage.

Aware of this background, you know how all of these quarreling have produced deep scars on Aemond.

“You should be whoever you want to be, you know”, so you say, holding his hand. “The world is yours if you so wish, Aemond.”

Reclining against the chair, he says nothing for a while, appreciating the song, the beer and… when looking at you, your company.

“You are too good for me, Y/N”, he murmurs, before taking a sip.

***

But she wears short skirts. I wear T-shirts. She's Cheer Captain, and I'm on the bleachers. Dreaming about the day when you wake up and find that what you're looking for has been here the whole time…

You are coming back from jogging when you see her for the very first time. Taller than you, more gracious, prettier and sensual in the way she walks, Alys Rivers is dressing short skirts and a white top that reinforces her curves.

You feel embarrassed, not to say envious, when looking at what you are wearing by comparison. Blue t-shirts and black pants, your college hat and the same cute ponytail.

Insecurity hits hard and you hate yourself for it. But truth is, one is never too old to be hit by intern instability.

You also notice Aemond is having a wild barbecue at his household. At first you are hurt for not being invited, but when carefully noticing who is there, you realize it’s better for you not to get yourself involved in this kind of matter.

Exhibited like a trophy is his girlfriend, surrounded by Aemond’s Hightower cousins. You are not entirely ignorant of their illicit activities and considering Aemond’s rebellious nature, it does not shock you those are his new friends. It is more disappointing to feel overshadowed by that woman.

In the midst of this noise, Aemond feels the weight of your gaze. There is so much to be said. This is not the barbecue he wanted to do, he’s never been a lousy man, rather being introspective.

But one miscommunication, and you go back inside, heading to the shower as you carry disappointment with you.

If you could see that I'm the one who understands you, been here all along. So, why can't you see? You belong with me…

It’s been two weeks. What was meant to be a surprisingly good reunion with your childhood best friend is proving to be another heartbreak you thought you’d not have to face since Jacaerys Velaryon cheated on you with his own cousin.

You opt to open a beer and throw yourself in the couch, watch some Netflix cliche, refusing to voice out your inner frustrations. What the fuck were you thinking again? Projecting romance to your life like you are the protagonist of some Christmas movie is old news.

It’s when a knock on the door scares you. Who might be in this hour?

Oh, I remember you driving to my house in the middle of the night. I'm the one who makes you laugh when you know you're 'bout to cry. And I know your favorite songs. And you tell me 'bout your dreams. Think I know where you belong. Think I know it's with me.

“Hey”, you are surprised to meet him.

Aemond is dressed in his old jeans and a white blouse. He stands before you not with the happiest faces.

“Come here, darling”, you welcome him with opened arms. “What the hell happened now?”

He is silent like always, but promptly accepts your embrace. Only then, carried to your couch, he slides to your side and takes your beer.

“I fucked shit up, Y/N.” He avoids your merciful and comprehensive gaze.

“I doubt it. But what you have done now? And where’s your girlfriend?”

“We had a fight”, Aemond rolls his eyes, sinking in the couch. You realize he’s still drinking of your beer, but you don’t mind it. “She’s very possessive. I was talking to Helaena… My own sister, and she keeps being demanding.”

Then he looks at you, expecting some answer. It takes you by surprise, though, when he changes topics abruptly by saying:

“Why did you have to go?”

“Uh?”, you barely flutter your eyelashes at it. “What are you talking about?”

“You moved out 12 years ago to High Garden”, and here comes the subtle resentment.

You take his hand and play with fingers, head resting on the back of the couch as you and him lock gazes.

“I had no choice upon the matter. I was transferred to another school because of my father. You remember that.”

“You never sent me an email.”

“Neither did you.”

For a moment there is silence hanging between you. And then Aemond says:

“I’ve heard you dated that Jacaerys lad.”

You scoff.

“How’d you know that?”

“He is my fucking nephew”, and for some strange reason this makes you two laugh. “I’m sorry about how things ended for you two. Harwin was pretty excited for having you as his probable daughter-in-law.”

“You don’t like this idea very much”, you smile at his subtle jealousy. “Something which we know wouldn’t work out well.”

Aemond’s eyes move to his hand intertwined with yours. A view that warms his heart.

“What happened?”

You opt to drink beer instead of responding him. As he studies you, Aemond spots some hurt behind your y/c eyes.

“He didn’t…”, Aemond cannot consider this option. Even so, the mere idea angers him. “Did he?! What a fucking asshole!”

To your surprise, he’s the one to hug you.

“I’m sorry, Y/Nickname. You deserve better.”

You sigh heavily, resting your head against his shoulder. For a moment, it feels like you are teenagers again and it’s you and him against the world.

“It’s all right. It’s in the past now.”

The rest of the evening is spent in between sweet talks, beers here and there. Until all breaks with a call.

“Ugh”, Aemond grumbles. “It’s her.”

As if you are reminded that this bad boy prince is nothing but a long time rebellious friend, you set your heart at easy with the crude dose of reality.

“You should better get going”, you help him stand. “After all, you have a girl waiting for you.”

Aemond rolls his eyes.

“I don’t like how this sounds.”

An intense stare.

“Am I lying, Targaryen?”

He laughs quietly.

“No, Y/LN. I hate you for it.”

For now you two follow separate ways. For now.

***

The more time Aemond spends with you, the more drawn he is to light. Whenever he’s with you, he can talk about his dreams—he wants to have an independent career, nothing related to law or politics, perhaps something related to humanities—, he is allowed to have hopes and become a better person. All of this is possible when he’s with you.

But now… far from his family and emerged in this bitter darkness that his temperamental cousins and his girlfriend aligned with his dark desires, he’s realized how wronged he’d been.

He is broken, he knows it.

“Where have you been?!”, she calls him out. “I’ve been calling you for hours.”

And he decides he’s the author of his life. He let others broke him, but that’s enough for him.

When looking at Alys, Aemond knows now how he belongs with you. He just hopes it’s not too late to make it right.

“I owe you no explanations of what I do, or wherever I go. And you know what, Alys? I’m tired of this life. Just… go away.”

She wants to argue, but he doesn’t have any patience for it. The door is open and Aemond makes it clear with his deadly silent moves. He’s a winner now.

“Fine. But you’ll regret it.”

Empty words that the wind takes away after he closes the door. As he looks at the phone, he knows he needs to call the other woman whom he should have never hurt in first place.

His mother.

***

Standing by and waiting at your backdoor. All this time how could you not know, baby?

You are preparing to leave to your college when he crosses your path.

“Hey. Where the fuck are you going to?!”, Aemond asks you, paled when realizing that he, in fact, might be a little late.

“I told you I’ve only had a few weeks here, A. I’m going back to college”, you side smirk. “What’s that face? Why are you looking so serious?”

He swallows his pride and then takes your hands in his, clasping them together.

“I love you, Y/N.”

You swear you are about to faint. And maybe your sudden paling makes sure Aemond is holding you tight.

“Don’t pass out, woman”, he chuckles lightly, though you spot concern in his eyes. “I mean it.”

“B-But Aemond”, you say, struggling to understand. “I am going back to college for my final semester and I thought you were in a relationship?”

Cupping your face with his hands, he turns at you with the sweetest smile you’d ever seen, saying:

“That should not be a problem. I’m on my way to be with you. I shall rent an apartment there and work at my father’s company all the whilst I start to study history. I’m getting my shit together, Y/N, and have all this to thank you for. As for my relationship, I broke up with her. Can’t you see I’m doing all of this for you?”

“Oh Aemond!”, you sigh in content before leaning to kiss his lips.

He smiles in secrecy as his hands slide firmly on your waist firmly, kissing you in return. It is as it should be. He belongs with you, after all.

***

• Epilogue.

Twelve months later…

“What are you reading today, my dear?”, you recline back in your chair and turn your head to look at him, heart melting before the sight of him all concentrated.

Lowering down his book, Aemond smiles quietly at you.

“The history of Westeros through the chroniclers. Quite an interesting reading”. He puts the book aside and pats a seat next to him at the large bed he’s in.

You leave your computer there and happily complies, soon adjusting to his arm, smiling as he plays with your ponytail.

“How’s work today?”, he asks you, in turn.

It’s winter and it’s snowing, but you’ve managed to work from home. A good excuse to be around your betrothed—oh yes, he proposed you recently, about six months after you two moved in together.

“Not very demanding today, thankfully”, you turn at him and smile fondly, caressing his cheek. “Your mother wants to spend Christmas with us.”

Your rogue prince, despite cutting his hair and dressing better, straightening his path, remains temperamental when it comes to his family. He rolls his eyes, before sighing.

“Really now? What did you say?”

You bury your head against his chest all the whilst Aemond wraps you around his arms, throwing blanket over you two.

“I told her to come. I think we might expect everyone, really. I hear she’s in good terms with Rhaenyra too.” Apparently, the two had had a bad fight last autumn.

“Oh no”, he groans.

“Look at the bright side, Leana, Aegon and Daeron are coming as well.”

“This apartment isn’t big enough for all of them, my darling”.

You raise your eyes to meet his. He’s so adorable wearing glasses, you thought.

“It is, it is. I’ll make sure everything is going to be perfect”, you smile warmly.

Aemond smiles back at you.

“Damn, I cannot say no to you. Fine, do your best. And since we are welcoming this big dysfunctional family of mine, how about inviting yours too?”

You tilt your head, smiling.

“Really?”

He scoffs.

“Of course, silly head.”

You lean to kiss his lips.

“I love how Christmas man you’ve become, sweet Aemond.”

He chuckles quietly.

“That’s only because you’ve made me one, darling.”

Leaving aside his book and glasses, he leans to kiss you deeply and you return it passionately. This afternoon is surely going to be warmer than expected…

#ewan mitchell#aemond targaryen#house of the dragon#aemond targaryen x female reader#aemond targaryen x y/n#house targaryen#lord Aemond#prince aemond Targaryen#taylor swift#you belong with me#fearless (taylor's version)

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

what ive gathered from skeppy’s new video

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wolf’s Price

[First] [Previous] [AO3] [ko-fi]

XVIII. Remade

5.2k

I hadn’t written to anyone since winter set in and we stopped sending couriers. Whatever was going to happen to us in the spring, I decided that it was time to write to my sister.

I had three brothers, two older and one younger, and a sister on either side of me. Eva was the older, born just a little over two years before me. She told me I was stupid, when I enlisted. “You don’t know when to shut your mouth. If you’re captured, the Sarenns will cut your tongue out before the day is over.”

I made some joke then, about how I’d rather lose my tongue than my head. She punched me in the arm, then, left me with a bruise for near a week. “Don’t joke about that! You know what Sarenns are like—they worship wolf devils and leave unwanted babies out in the snow as sacrifices. If they get your hands on you, they’ll probably cut your throat over an altar and sacrifice you to one of their animal gods.”

“I’ll be careful then,” I told her. “After all, all I have to do is be smarter than a Sarenn, right?”

“It’ll be a challenge for you, I know.”

I had written to Eva a little bit about Lya, not sharing any of Muras’ suspicions with her, of course. Eva hadn’t thought much of either of us, bringing some unknown Sarenn woman into our home when she was a near total stranger to us. She didn’t think much of the fact that she had previously lived with Heita, either. I’m sure even you don’t think it’s entirely a good idea to pick up a new mistress from Emiran’s old lover.

I didn’t know, when I sat down, what I wanted to say to Eva, but I supposed if there was a possibility that I was going to die, she would at least want to know why.

I imagine that by the time you get this, I wrote, I’ll already have been declared a traitor. Once I started it was hard to stop. I had never cared much for keeping secrets, and whether or not Eva would be sympathetic when she read my letter didn’t matter. Like as not, I would never see her again. It would hit our father quite hard, I supposed, and no doubt my brothers would be quick to distance themselves from me. I didn’t know what our mother would do.

I knew at least that, if nothing else, Eva would read the letter to the end.

We were sent here to be killed, so I can’t say I feel much remorse about actually committing the treason that the prince is so afraid of. Kressos has always been very good at making its own enemies.

I spent a long time writing that letter. Cutting whole sections from it, rewriting them. Muras was always a better writer than I was, but then, I’d never poured the kind of effort into it that he did.

Lya was out most of the day with Veland, and she must have washed his hair, because she came back to the room to comb through his hair in front of the fire until it was dry, singing quietly to him in Sarenn. Veland was picking up on it, singing parts with her, and mumble-mouthing others. Lya parted his hair and began to braid it, smooth and tight.

I watched them for a while, because it was easier than staring at my unfinished letter. When she was done, Lya kissed the top of his head, and Veland ran off to play with the other children. Lya rubbed her belly, and stretched her feet out in front of the fire with a sigh.

“How are you feeling?” I asked.

“Tired.” She let her head fall back on her shoulders. “Little one was kicking my ribs all night.” She closed her eyes. “What are you writing?”

“A letter to my sister.”

“Are you close?”

“Used to be closer.” I gazed at her another moment, the weariness in her shoulders. “Why did you come to Kressos, after all that?”

Lya opened her eyes slowly. “If you were looking for the woman that I was,” she said, “would you ever think to look for her in a Kressosi household?”

“Not as a maid,” I admitted, “not as Kaspar Heita’s clerk, that’s for damn sure.”

Lya nodded, and looked back to the fire. “Nor would anyone think to look for her in the bed of the man who killed her king.” She rubbed her belly again. “Every choice I’ve ever made since I left this place had a reason.” She laughed softly, shook her head. “If I’d known then that Kaspar knew the both of you…”

“He knows Muras. He tolerates me.” I shuffled the pages of my letter together, turned them over on the desk. I scrubbed over my face with both hands, put my elbows on the desk. “You know I love you, don’t you?”

Lya was quiet a long time. “I love you, too,” she murmured. “It would be so gods-damned much easier if I didn’t.”

She pulled herself up out of the chair, and came over to the desk. She put her hand on the back of my neck, and kissed my temple. I wrapped an arm around her, and pressed a hand over her middle. “I’m sorry I’m not a better man.”

I half expected Lya to ask what had got into me, that I was so morose, but she didn’t. She just ran her fingers over my hair, and let me lean into her side.

“I have to go,” she murmured, “I have things I need to do in town today.”

“Keep warm,” I said, “and keep safe.”

“I’ll do my best.” She tied a scarf over her head, over her ears. She touched my arm as she left, and whatever unspoken thing passed between us, I knew one thing for sure. She meant to leave us soon, and I didn’t know to where, or what end.

#

I thought hot water might clear my head, or at least make me better at pretending I was the same as ever. I took my time scrubbing from head to toe, and wiping a mirror clear enough that I could shave. It was a tempting thought, to let my hair grow long and a beard start on my face, just so I wouldn’t stand out so damned much whenever I walked through the town. I was one of the only Kressosi men not in a uniform, and among the first words of Sarenn I had learned was beardless. Not a kind word, that.

I had asked Lya about it once, why the beards were so important. She had scoffed and said, “Growing a beard is important because Kressosi men shave them off as much as it is any other reason.” The hair seemed to be the really important thing, as she had explained it to me. A braid told anyone who looked at you just how important you were. The higher it began on the head, the more complex it was—the greater the wealth and power of the person wearing it.

I had seen enough of that when we took Morhall. The princesses with their hair braided as intricately as lace, with colored ribbons and wire and glass beads, the braid beginning just behind their hairlines. All the servants had worn their braids at the nape of their necks, much simpler plaits with only one ribbon, or beads that were made of bone. A code of status that was only unfamiliar to us because it was in their hair, not just their clothes.

Some Sarenn lords had started to shave their beards, since the war had ended—but I knew of not a single one who had cut his hair. That, I supposed, was much too sacred.

I wasn’t sure I really understood what ‘sacred’ meant. I had never been the pious type, and if I’m honest, I was even less so after my brother became a priest. To me, worship always represented something I couldn’t feel, some other way in which I had failed my parents.

But I had seen ghosts. I had seen Lya call up wolves with a horn.

The Sarenn believed in fate, and if there was anything to it, I supposed there must have been a reason for us to all come north again. There was a reason that Lya had found her way to us, that we had been the ones to bring her back here. What it was, I couldn’t have pretended I knew.

I dressed warmly, and decided to go for a ride. I was growing used to elk, and their particular ways. The cow I took was a good tempered creature, not giving me any trouble in putting on blanket and saddle. She snuffled at my pockets, looking for grain.

The wind was bitter cold, but there was something else: it was snowing again. Funnily enough, the return of the snow signaled the coming spring, that the worst of winter was over. Before that, the air was too cold and dry for snow to fall. Snow falling again after midwinter meant that the world was beginning to warm.

I made my way out of town, down along the fields. I didn’t dare go out to the trees alone, not even in the middle of the day. The trees hid wolves and snow lions and bear dens, and I wanted to be able to see all of those things coming.

I remembered why I didn’t like spending much time alone as I rode. It gave me far too much room to think, to wonder and to worry. I stopped the elk under a fringe of old maples, listening to the quiet as the snow fell around us both. The cow’s breath steamed on the air.

“Have a busy mind, don’t you?”

I jerked the reins in surprise, and the cow snorted and shifted. I hadn’t seen the beggar who now stood under the trees, his back against the biggest and oldest. His feet were bare in the snow, and he leaned heavily on a staff to keep his weight from a club foot.

He raised a hand to the elk. “Easy,” he murmured. “You know who I am.”

The cow pressed her nose against his palm, and I felt her relax.

“Who the hell are you?” I demanded.

The beggar was old, scarred. His beard was scraggly and almost to his waist, and he wore a hood over his braid. He gave me a smirk that I didn’t like in the slightest. “Some say that winter is the season of death,” he said, “but men like you know that it’s spring that’s the season for war.” He reached under his old and worn coat, producing a flask. He took a drink, and offered it to me. I stared back at him until he shrugged and put it away. “You Kressosi aren’t much for hospitality, are you?”

“Who are you?” I demanded again.

“An old friend of the she-wolf you sleep beside,” he said, leaning on his staff. “You know what’s coming, don’t you? The inevitable, the caged wild animal having enough and finally going for the killing bite.”

Everything in me rebelled at this old man’s proximity, the kind of fear that’s beaten out of you in soldier’s training. Even if my eyes couldn’t see what was so dangerous about him, something else in me knew. I pulled the elk away, drawing distant. The old beggar smiled. He patted a hand on the gnarled old trunk of the maple. “The corpses of men were once hung in these trees before a war,” he said. “As sacrifice. A great many years ago, when there was no Saren, and its people fought each other. Then your folk came along, and such hangings moved south, and they only happened once a war had already begun.”

I had seen the trees he spoke of, once. Kressosi soldiers beaten to death and strung up to rot. I had seen, too, the swaying of cut ropes when the Sarenn had known we were coming, and cut down the dead before we could find them. I heard it said that they chose maple trees because the maples were too benevolent to allow the ghosts of the dead men to haunt them afterward. Their souls would be kept at bay by the same branches that had held their corpses. The same maples that were tapped for syrup at the earliest blush of spring. I had always wondered if they had a story for that, too—this tree that bled for them, that they fed with blood.

“You’ve a fighter’s spirit, I can smell it on you,” the old man said. “You’re not the kind to lay down and die.”

“What do you want?” I asked, scanning the trees for anyone else I might not have seen, regretting that I had come alone, and with only a pistol.

“I want the fight,” the old beggar said, “I want the blood. Deep down in your gut, you want it, too. You know there’s no honor in a quiet murder.”

I stared at him, said nothing. The old beggar smiled, and nodded his head, raising his flask to me as if in a toast. “Every wolf needs its pack. You could content yourself with being a dog, or you could grow into your teeth. The decision is yours.” He began to whistle a tune to himself, and limped off along the edge of the fields, dragging his club foot behind him.

“What’s your name?” I called after him.

“I have many,” he called back. “Ask the she-wolf.”

#

There was a brawl at a tavern, in which a young Sarenn man was killed. Muras found the soldiers who had been there, and lashed them all, regardless of whether or not they had started the fight. He didn’t care, and he told them so. Peace was a fragile thing, and they could not rely on might to maintain it. He had them lashed publicly, to settle the Sarenn discontent, and after that, no soldier was allowed outside of Morhall after dark.

The men resented the curfew, but it helped me breathe a little easier. I knew Lya still went out at night. I knew that Muras hadn’t asked her to stop.

We were waiting up for her, when she came back to our rooms after midnight. She looked at us a moment, and took the scarf from her hair. There were beads in her hair that I hadn’t seen her wear before, I was reasonably confident they were made from ivory or bone. “You didn’t have to stay up on my account,” she said, beginning to take off her coat.

Muras couldn’t bring himself to look at her, and I watched the wariness grow on her face. “I need to tell you something,” Muras said, staring at the fire.

Lya held onto her coat, as if it might be a shield. “Tell me what?”

Muras drew in and let out a breath. “When I first saw you in Jasos,” he said, “I thought—I’ve seen her before.”

Lya was still, did not move.

“I wasn’t sure where, at first,” Muras said. “But I knew I’d seen your face. You were too familiar. I wondered if maybe it was just that I had been in Kaspar’s circles, once, but you said you had only come to Jasos a few years before, so I knew it couldn’t be that.”

Lya looked at me, and I looked away. I couldn’t face her either, knowing that we had kept this from her for so long.

“As I talked to you, as you told me a little about where you were from—I started to piece it together.”

“Stop,” Lya said, her voice tight.

“I knew I had to keep you close, until I was sure,” Muras said. “I couldn’t take the chance that I was just imagining things—”

Lya took a step back and stood against the door. Her voice was deathly quiet. “You knew.”

Muras was quiet, not looking at her.

“You knew. This whole time.” Lya moved before either of us could react, grabbing her wolf mask off the wall and throwing it at him. “You son of a bitch, you knew!”

The mask struck Muras in the shoulder as he tried to move away, hitting the floor with a thud. Lya shook with rage. “The entire time you knew and you let me hide it from you! You let me be afraid!” She looked to me, and grabbed the next thing she could reach—my sword in its sheath. She hit me with it, hard enough to bruise. “You let me think he didn’t know! That you didn’t know!”

“Lya—” I started.

“Shut up!” Her face was flush with rage. “You bastard! You—” She let out a stream of Sarenn obscenities that I understood maybe a quarter of, hitting me again and again with the sheathed sword until I wrestled it out of her hands.

Muras tried to intervene and she slapped him, her nails scratching an arc across his face. Red blood welled up in dark beads. “You let me bring my son here,” she snarled. “And you knew.”

Muras held onto her wrist, gazing back at her. “He is Corasin’s son, isn’t he?” Muras asked, soft.

Lya spit in his face, and called him a Sarenn word that I was pretty sure impugned more than just his honor. “He is my son,” Lya said, “he has no father but the Wolf.” She jerked free of Muras’ grip, and gave us that same burned-eyed look I had seen in her before. “You knew what I was, and you made me come back to this place. To this tomb.”

“Lya,” I said, drawing her furious gaze. “I’m sorry.”

She looked like she wanted to kill me for saying it. “It is far too late for that.”

I reached for her, and she slapped my hand away. “Don’t touch me.”

“I want to help you,” I said, “you have to get away from this place.”

“Yes,” she said. “I do.” She took her coat, and the scarf, and fled.

#

I couldn’t find Lya anywhere that I looked for her, nor Veland. It was difficult to search without raising the alarm—though I knew she could not have gone far, as Bili was still in the stables.

Muras had not said anything since she left, but I could see in his eyes that he was maybe a breath away from panic. “I’ll check the lodge,” I said, “if she’s gone into town, that’s where she’ll be.” I knew even then it probably wasn’t a good idea to be going about alone at night, but I was more concerned about Lya and Veland. Perhaps I really was the fool that Eva made me out to be.

I took the same cow elk I had ridden when I encountered the strange old beggar. The snow was falling heavily, fat flakes that muffled everything. I scanned every head in the street, looking for the red flash of Lya’s scarf.

Something felt off, as I drew nearer to the lodge. It took me a moment, as I tied the elk to the post. There was no smoke coming from the chimneys.

I opened the door to an empty hall. Dark, still. I stared at the empty lodge, uncomprehending. I knew they had been there the day before—the lodgekeepers, the sick, the dying. Where the hell could that many people have gone?

The ashes in the hearths were cold. Where had Lya been all night, if not here?

“You won’t find her here, pup.”

I whirled, hand on my pistol. The beggar from before stood in the door, but he was—different. Younger, somehow. “If you know where she is,” I said, “tell me.”

The beggar shook his head, shrugged. “She doesn’t want to be found. She’s gotten very good at passing unseen.”

“It’s too dangerous for her to be on her own.”

“Who said she was alone?” the beggar asked. “And who said being with you was safer?” He laughed, picking under his nails with the point of his knife. “You’ll have to run quick if you mean to catch up to her.”

“If you know where she’s going—” I started

“You already know, pup,” the beggar said. “She already told you.”

Home. She was going to Arborhall. It wasn’t spring yet, but what did that matter to her? She had left this place through a snowstorm that should have killed her. Why should she have to wait for the thaw?

I raced back to Morhall, the elk flinging up snow behind us. The stablemaster swore up and down that no one had been out since I left, even when I put a pistol under his chin. “Are you drunk or blind?” I demanded. “That goddamn bull is gone!”

#

Bili was gone from the stables, as was another elk. Lya’s things were missing, and Tyna’s room had been stripped bare. No one had seen them leave.

I didn’t understand. Couldn’t understand. How could they vanish, just like that? Two women, one of them heavily pregnant, a seven year old boy, an entire lodge full of people—gone.

She had to have been planning this. Since she spoke to Spider, if not earlier. How long had she been planning to disappear on us?

Muras stood over the fire, staring into the coals. “Gone to Arborhall… how long, do you think, it will take her to get there?”

“Here’s a better question,” I said, “how long do you think it will take us to get there?”

“That’s madness,” Muras said.

“What about this winter hasn’t been mad?” I demanded. “What about us finding Lya like we did wasn’t mad?” I threw his coat at him, tired of taking no for an answer. “If you don’t get up,” I said, “you’re never going to know if you have a son or a daughter.”

Muras held his coat a moment, and said, “I can only die once.”

“What?”

“Something Tyna said,” he murmured. “For all the deaths we caused here, I can only die once. That it’s a pittance.” He looked at me, a new light in his eyes, or rather an old one that I had missed, and stood. “Everyone knows she’s missing, so it will look odd if only we go out looking for her. But we can’t have a party with us, either.”

I almost smiled with relief. This was the Muras I knew, his mind turning over a puzzle, the Muras who knew that he was lucky. “We can send a party off on a wild goose chase, with a promise to join them later, cutting out the way we mean to go.”

Muras nodded, and said, “We can only take so much supplies.”

“If anyone can get the two of us out of here alive, it’s you.”

“Yes, well, we’re damned lucky you’re a good hunter.” Muras pulled on his coat. “We’ll send them into the forest to look. Some rumor about the wolf cult headed that way, with orders to camp when night falls, and that we’ll join them then. At sundown, we’ll take our elk, and when it’s too dark for us to be seen from here, we’ll turn south.”

And hope that our rifles were enough to keep wolves and snow lions away from us until we found a place to sleep. The sky had been a moody dark grey that promised snow. If we were lucky, if there was snow falling when we left, it would hide our trail from anyone who might try to track us.

Muras picked up his sword, held it a moment in his hands, the polished dark sheath gleaming in the low light. “We’ll never know anything but war, will we?”

“I don’t know,” I said, “maybe when they make you a soldier, that’s the only way you can look at the world.”

Muras shook his head. “I can’t accept that.” He looked at me, let out a breath. “We will live long enough to see peace,” he said, “long enough that we’ll no longer be soldiers.”

I laughed a little, and Muras looked at me curiously. “Nothing,” I said, “it’s just good to have you back.”

#

We orchestrated it like theater, pulling together search parties. The commander’s pregnant mistress and child had gone missing, along with his personal physician, it was natural that Morhall would be in an uproar over it. Muras spun a beautiful tale about believing that the wolf worshipers had spirited them away into the woods, sending three groups in different directions. We would meet up with those headed northeast by sundown, he told them, once he had put someone in place to keep Morhall running in the meantime.

Muras was no fool there, either. There was an ambitious young major who we both knew was aching for a command post like this one. Muras sent him out searching, and found instead the near-incompetent young man we both knew was only there because his uncle was quite wealthy. Such a young man could be trusted to survive until spring, when someone came looking for us and found us long since missing, but wasn’t useful for much else. He certainly would have no idea what to do when we didn’t return, except carry on as acting commander.

We put together enough food to carry us a few days, no more, so as not to risk suspicion from the kitchens. After that, we would have to be damned lucky to get out of the north alive.

I left my letter to Eva deep in the pile of letters that would go out in the spring. I saw that Muras had written several to Tomlin. I wondered if any of them were like mine, explaining the choice we were about to make.

Two young and fit gelding elk would have to carry us. I didn’t dare load them heavy—we needed to be swift, and we couldn’t be seen taking all of our worldly possessions, either. So, I was careful in what I chose. Our warmest clothes, our best boots. A few things that I believed we could not do without or could not bear to leave behind. Everything else, we could afford to lose.

Theater, all of it, and the best damn show we ever put on.

Muras poured over a map, trying to guess which way Lya would have gone, and where we might catch up to her. She had told us enough of Hasi routes, and they would be on their way northward now, following the thawing plains. Reaching the Hasi would give her a chance to hide among their numbers for a time, even as she headed in the opposite direction. She spoke their trade language, she knew them as friends who had helped her before. Through Veland, they were a sort of kin to her.

Our biggest obstacle would be convincing any Hasi we encountered that we were friendly.

In the stables, I watched Muras secure a particular pouch in his saddlebags that I knew well. The one gift his mother ever gave him. He noticed me, and paused. “I suppose it seems foolish,” he said, “after all these years.”

“No,” I said, “it doesn’t. Not after everything we’ve survived.” Maybe his mother was a witch, maybe it was all in his head, I didn’t know—but I wasn’t about to go questioning whatever had kept him alive all this time. I had too many questions about everything else to worry too much about that.

The sun was going down as we set out, though you could hardly tell, the clouds were so dense. We started out north, carrying our lanterns, and as the city grew smaller behind us, snow began to fall.

I threw my lantern into the snow, to prove to whoever came looking that we had set out in that direction, and we arced southwest, swinging wide around the city. Our tracks would be gone by morning, leaving no trace of what direction we had gone. Muras and I rode close together, a rope thrown between us, so we could not lose the other. It reminded me of that march, being out in the dark and the snow. The wind picked up at our backs as we rode, pushing us south. No one would be able to look for us until morning, and even then, only if the weather allowed.

Across the dark fields, past the maples where I had met the old beggar, down the sloping hills and along, only Muras’ lantern to light the way, a fragile flame protected by a pane of glass he had to wipe the snow from every few minutes. I don’t know how long we rode, the wind at our backs, but I knew we were both thinking the same thing—that to stop in the open was to invite the cold to steal our breaths.

We found the beginnings of trees, a few blown down. Muras paused, scanning the dark landscape. The wind was sharp and cold, and I could hear it howling in the distance. Really, I couldn’t be sure if it was the wind, or a pack of wolves, but I wanted it to be the wind, so that was the only possibility I allowed.

We found the first edges of forest, and hunkered down behind an old log big enough to shelter both us and our elk, which we huddled against to sleep. We couldn’t have built a fire even if we dared to, so I wrapped a blanket around me and Muras both, my chin tucked against his shoulder.

Muras let out a breath, listening to the wind over us. “Strange,” he said, “it doesn’t feel as monumental as I thought it would.”

“What doesn’t?”

“The leaving. Becoming a traitor.” Muras shifted, touching my arm. “It didn’t feel monumental when I killed Corasin, either, but I thought that was just—the context of everything else. How could I celebrate when we had done what we did?” He paused, sighed. “But maybe it’s just that the stuff that makes the story of one’s life never feels momentous when you’re doing it.”

The elk grunted quietly and stirred, one of the geldings bringing his head around to rest on my back. “Of course it doesn’t. When you’re doing it, it’s just the choice you made to stay alive. It only becomes significant later, when you have to fit it in with everything that’s happened since.” I closed my eyes, held Muras close. “I’m glad you chose this.”

Muras ran his fingers across my sleeve, head resting on the side of the elk. “I’m sorry it took me so long.” He was quiet a while, long enough for me to almost fall asleep. “What if we’ve lost her? If this time, she stays hidden?”

I shifted, and thought of the beggar with his club foot. I want the fight. “I don’t think she will.” I watched the snow piling up around us. “I think she’s just looking for a good place to dig her heels in, call home again.” I pulled the blanket higher over us. “Seems to me our priority—after surviving, of course—is figuring out what it’ll take to make us Sarenn.”

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wolf’s Price

[First] [Previous] [AO3] [ko-fi]

V. Howl

5.2k

I brushed my hair while Lady Tyna ground herbs in her mortar and pestle. We had come to something of an uneasy truce, in the days following our departure from Wetasur, and though I still did not trust her, I preferred her company to that of the soldiers, who only treated me with any kind of respect because they feared Muras’ reprisal if they acted inappropriately. Even if I did not like her, we could talk in words that were familiar to us. We didn’t have to explain ourselves to each other.

Our party was camped along the banks of a small river which ran cold and fast. I had quietly made the appropriate offerings to the god of the river, while no one paid me any mind. I didn’t wish for anyone to drown or take a chill in its waters.

One of the soldiers played a wooden flute, leaned up against a supply wagon. Muras was brushing down his elk, and Todd was playing cards with three or four soldiers by lantern light. It would have been almost peaceful, except that every now and then the men would all look up, hearing the distant roaring of snow lions. The soldiers kept their rifles near at hand, and their eyes on the darkness.

“Do you think we should tell them lions only kill men in winter when game is scarce?” Lady Tyna asked, scraping her powdered herbs into a pot of boiling water. She made the same tea every night, said she couldn’t sleep without it.

“I’ve found it does little to ease their fear.” I had tried to tell Muras as much, but it had not prevented him from ordering a watch for the previous few nights, and it would not stop him from ordering another that night. It made the men feel better, to have a watch.

We had begun to come across evidence of the Atsa’s passing. It was difficult to mistake mammoth dung for anything but what it was, and the old campfires smothered in dirt that followed the mammoth paths made it certain.

We came across a dead mammoth the following day. It must have perished the winter before, because what was left of it was mostly bone and scraps of weathered hide, the flesh long since scavenged or rotted away. The tusks were sawn off, and the ribs gone. The Atsa used them to construct their mammoth hide tents. The teeth were gone, too, for jewelry, for carvings.

“I always forget how big they are,” Todd murmured, standing in front of the skull. “I never saw a mammoth, before I came to Saren. Then the first one I lay eyes on… it was in battle.”

I rested my hand on his arm while Todd told me about it, his first year as an officer, “green as a spring sapling and twice as dumb.” He was stationed at a garrison on the Kressosi side of the Lor, up in the east where the river was narrower. His commanding officer sent them across on riverships the moment the ice melted, counting on Saren to be weakened from a difficult winter.

They had forgotten that the Hasi were still in the south, and that they were not inexperienced with Kressosi raids. While the Sarenn city had bunkered down and sheltered the women and children, the Hasi and other Sarenn men drove the mammoth herd into a panic down to the river, where they crushed ships and men alike. Kressosi muskets couldn’t harm them enough to do anything but make the panic worse, and enrage the mammoths.

“I jumped ship and swam back to shore,” Todd said, “current took me nearly a mile downriver and I had to walk back on a broken leg, with bodies floating down the river.” He shuddered slightly at the memory, and I squeezed his hand.

“The Litira Hasi say that in the old days, when it came time for war, their men would use a secret ritual to communicate with solitary males, become one with them, and take them into battle.” I had used to love listening to Hasi stories, but that one especially. I imagined the Litira warriors, with blue and red whorls painted on their faces, going into battle with mammoths, throwing spears and firing arrows from their backs.

“Well,” Todd said, “I hope for our sakes they’ve forgotten how to do that.”

#

Muras was bent over a letter to his twin sister on a night we stayed in a roadside tavern with a leaky roof and the wind whistling around the window panes. In Kressos they say twins are lucky, signs of good fortune. Tomlin was the only of his sisters that I had ever known him to write to.

“Are you going to eat?” I asked. “I didn’t see you in the dining hall at all, and they’ll be putting the food away, soon.”

He had grown moody, and that worried me. Kaspar had been given to moods, too, and they had usually been accompanied by whiskey. Muras was not a drinker, but I did not know what he was, when a mood took him.

Muras looked up, surprised, as if he had forgotten where we were, what time it was. “Oh—gods. Is it any good?”

“The food? It’s as good as you’ll get, this far away from anything. Suffers for a lack of pepper or ginger, but the meat’s good and the rice is cooked well.” I put a hand on his shoulder. “Go eat. Your letter will still be here when you get back.”

He went, and I sighed, glancing down at the letter.

I would say I didn’t mean to pry, but the truth was I hoped to learn if something was wrong, something he might confide to his twin but not to me.

And I saw my own name.

Lya doesn’t speak the whole of it. She answers my questions, but I always have the sense she’s holding back, concealing something. She claims she dislikes to speak of her past, but I think she’s deflecting me, that whatever she’s hiding, she has good reason to fear.

She hasn’t been the same since we crossed the Lor. It’s as if some spell has been cast over her. I can hear you telling me not to be so superstitious already, but this place, Tomlin—it’s enough to make you believe that everything the Sarenn say is true.

After a year in Morhall, I imagine I’ll be convinced of witches and trolls, too.

I scanned the rest of the letter for my name, but didn’t see it. Hands shaking, I tore myself away.

My bag sat on the end of the bed. I plunged my hand inside, seeking out the horn Weta had given me. It was cool to the touch, the old ivory yellowed with age. I ran my fingertip along the trumpet, the ivory wolf’s teeth. The pad of my finger caught a sharp edge, and I gasped softly, seeing a spot of blood smeared across the tooth.

The horn warmed in my hand, and I plunged it once more into the bag, my heart racing. Weta had not told me what would happen if I sounded the horn. All I knew was that it had been given to him by the Wolf, to give to me. “It was made, for one such as you.”

“Was this fated?”

Weta had laughed at me then. “Fated? No. You were chosen when you proved yourself, and that has made your fate.”

What it was I had done to prove myself, he hadn’t said, but I suspected I knew.

After a moment, I pulled the horn out again. It was warm now, as warm as my own skin, and the streak of blood was gone. It seemed different somehow, as if the wolf’s head at the trumpet met my gaze. Hesitantly, I pressed my lips to the bit, held it aloft.

Horns weren’t a woman’s tool. They were things of hunting, battle. I hadn’t even played with them as a child.

I lowered the horn, and gazed at it. Weta might as well have given me a sword, for all I felt capable of wielding it.

By the time Todd came upstairs, I was penning my own letter, the horn hidden safely once more. “Who’re you writing to?” Todd asked, rummaging through his bag for his nightshirt.

“Kaspar Heita,” I said. “I want to know how my son is doing.” I avoided writing Kaspar, if I could help it, but I loathed the idea of learning about Kip’s wellbeing secondhand, so every few months I sat down to pen a short letter, telling Kaspar I was well, and asking after his health, and Kip’s.

Concerning himself, he only ever said that he was managing, and then he would go on to detail everything about Kip that had happened since the last time I wrote. Every complaint, illness, joy and sorrow. Overall, he was a healthy, happy boy, and I always felt that—without saying so directly—Kaspar was hoping that it would be enough to bring me back.

At least writing him gave me something to think about other than the fact that Muras suspected me of keeping secrets and acting strangely.

“So what’s happened that you and the Tyna woman aren’t trying to actively tear each other’s throats out?” Todd asked, pulling his nightshirt over his head.

“You noticed?” I asked dryly.

“Surprised you haven’t let Bili trample her,” Todd said, sitting on the end of the bed. It was barely wide enough for two people to sleep comfortably, and I couldn’t imagine the three of us were going to be anything but cramped.

“She’s the only physician we have,” I said.

“Are you ill?” Todd asked, a note of worry in his voice.

“No,” I said. “Only pregnant.”

Todd went quiet for a moment, and I glanced at him with a smile. He laughed. “Muras will be over the moon.”

“Don’t tell him yet,” I said. “He’ll fuss terribly about Bili and I won’t be able to stand it. He’d have me going all the way to Morhall in the back of a cart with dozens of pillows.”

Todd laughed, and nodded. “Alright. I won’t say anything. Save it for when he needs cheering up, yeah?” He winked at me, and stretched out on the bed. I finished my letter and went to join him, curling up against his side.

“His family will never accept one of my children,” I murmured.

“They don’t have to,” Todd said, running his fingers over my hair. “Muras is the heir. Only acceptance that matters is his.”

#

When first I had joined Muras’ household, Todd had been wary of me. Less because I was Sarenn, and more because I had been a maidservant, abandoned a child and former lover, and he suspected me of aiming to pursue a higher social status through whatever means necessary. He warned me that it was impossible Muras would ever marry me, to which I replied rather coldly that I never again would be any man’s wife, no matter who he was.

I think it was that that allowed Todd to begin to trust me.

It was some months later before he told me why he knew Muras would never ask me to be his wife, even if he wished to.

Muras was his father’s only son, that I knew. His youngest child, born after even his twin, smaller and weaker than his sister. It was feared he would perish in his infancy, but he lived, and despite some illness when he was young, grew to thrive.

He had six elder sisters, besides Tomlin, and was close to none of them. The reason, Todd told me, was because their mother had turned her daughters against Muras and Tomlin—because they were the children of a kitchen maid.

By no means were the newly born twins the only children that resulted from Master Emiran’s indiscretions, but Muras was the only son who survived his first five years, and thus, was the only one legitimized with his father’s name. Because of that, Tomlin and Muras were resented by their half-sisters, those legitimate and those not, and Muras had spent a large part of his life seeking his father’s continued approval, with a few major exceptions.

The first, that he had joined the king’s army without his father’s consent. Master Emiran did not feel he could risk his only son, not when bloody conflict with Saren was as certain a fact as the sun in the sky. Muras felt he could not bear to live another year under the watchful gaze of everyone in that household.

The second was me.

My existence was tolerated because I was only a mistress, and a man with a mistress could still make a marriage that suited his status. If Muras sought to marry me, there would be scandal, and it was unlikely that his father hated his sons-in-law so much he would not disinherit Muras for taking a Sarenn woman of unclear standing to wife. For all anyone else in Muras’ family knew, I could have been born and raised in a brothel.

I took comfort in that knowledge. I had told the truth when I said I would never again marry. I had found marriage to be a prison through which there was only one sure escape, and it was not a position I would willingly place myself in again.

So long as Muras had no legal power over me, I could convince myself that I was a free woman.

#

One of the soldiers in our party was a young man named Keris, who blushed whenever I spoke to him. He was maybe twenty, and spoke easily enough to the men, even to Lady Tyna, but with me he grew shy and bashful.

It might have been charming, had I not been trying to ask him a question. “Master Keris, I am just trying to ask you when the traders saw the Hasi.”

“Sorry—sorry, Miss, they said it was—ah—a week ago.” He had turned pink as a rose, and finally having gotten what I wanted out of him, I spared him the continued torment of my presence, pulling myself up into the saddle and spurring Bili to the head of our little band. We had had little trouble yet—a cartwheel had broken and we spent the better part of a day affixing the new one—but the further north we went, the more anxious I grew.

Even when Saren was ruled by its own king, the north had been more feral than the south. It was a nest for thieves and highwaymen.

The sooner we joined up with a Hasi clan, the better.

Lady Tyna approached me on foot, staying well clear of Bili’s head. “Did you hear the rumors, too?”

I nodded. The traders we had camped with the night previous had only narrowly escaped a band of men calling themselves a militia, who had taken it upon themselves to attempt to liberate the trade caravan of its food and elk. We had soldiers, but we were a smaller party, and I was not eager to find out how confident this militia was in their ability to fight Kressosi soldiers. I would stick closer to the group, and trust that Bili was suspicious enough to alert me of anything he heard.

“I hope your wolf-magic is good for something,” Lady Tyna said.

So did I.

I touched my saddlebag, where the horn was hidden. I had grown paranoid of it being too far out of my reach, though I couldn’t have said what I thought I needed it for, or how it might help me.

It would be three days, before we again encountered a tavern. The soldiers feared the animals we might encounter. They would be wiser to fear the men.

I draped the wolf pelt across my saddle. The warmth of the sun almost made it feel alive, sometimes. I had taken to bringing it to bed, and if either Todd or Muras thought that strange, they didn’t say so to me. I felt safer with it.

That day the most exciting incident occurred when we came upon a herd of wild woolly rhino grazing in a meadow, and we had to make a wide half circle around them before we could rejoin the road. There were calves whose heads only barely cleared the top of the grass, playing on a stream bank, and a flock of cranes on the shore with them.

We camped on the leeward side of a hill, under the cover of aged cedars, and set off again early in the morning, crossing paths only with a small herd of deer, and several flocks of geese. At noon we stopped to rest and water the animals, eating dried meat, cheese, and wild berries as a supper.

We passed through a small canyon speckled with thin waterfalls that would be dry by the height of summer. Moss and lichen clung to the smooth stone, dripping water onto the narrow path as we made our way down to follow the creek until the road began again.

I felt, more than saw, the way Bili tensed. He came to a full stop on the path, halting our caravan. I held up a hand to keep anyone from calling out a question, watching the way Bili’s ears flicked, the snort he gave. I raised my gaze, scanning the brush that clung to the canyon walls.

It was the glint of a bayonet that caught my eye. I yanked Bili around, raising my hand to point, “Up there—!”

The shot missed me, musketball splintering the bark of a scraggly tree just to the left, and Bili tossed his head and reared, bugling. Muras shouted to the soldiers, and I wrapped Bili’s reins around one hand, turning back to face the men aiming down at us. I felt another shot graze my cheek with a sharp sting, and I kicked my heels into Bili’s flanks, hard.

There is a reason I prefer elk to horses. Bili leapt from the path onto the treacherous footing of the hillside, barreling to the men who had fired at us, to either trample or throw them. The men scrambled for higher ground, and Bili chased until he could chase them no further, bugling and shaking his head.

I reached back into my saddle bag, grasping the one thing that was still warm to the touch. There were more men, I knew there were, because there were no three men in all of Saren mad enough to try and attack a group of Kressosi soldiers without aid. I put the horn to my lips, and the sound it made wasn’t that of any horn.

It was a wolf’s howl, echoing off the walls of the canyon.

I lowered the horn, and heard my howl answered. A dozen or more wolves I could not see, howling from the hillsides. I looked at the men Bili had chased onto a crag, and called out to them. “Tell whoever leads you that the Winter Wolf will devour any man who harms a member of our party.”

One of them spat at me, called me ‘witch’ and other things less polite.

I answered, raising the wolf pelt high so that they could see it. “Tell whoever leads you that the woman who told you this is one who has spoken Vull’s name aloud, called him down from the ice, and lived to speak of it. Tell them that she made the wolves howl for her, tell them that she knows your gods by name, and that in warning you to flee she offered you a chance to save your own lives.” I stared at them, eyes burning. Let them think I was laying the evil eye upon them. “Vull will slaughter any who harms me and mine.”

A distant man’s voice called them to retreat, and I watched the men begin to climb, disappearing once more into the brush.

Snorting in discontent, Bili took us back down to the path. I held the horn tightly in my hand, and looked up, when Muras came to meet me. There was something in his eyes, something between fear and disbelief. “Lya…”

“We need to go,” I said. “Now. And get onto safer ground as quickly as we can. I won’t have scared them off for long.” I put the leather strap of the horn over my head, pulled my braid out so that it rested firmly at the back of my neck, and the horn fell against the front of my jacket. I spurred Bili to a trot, keeping an eye on the hillside, and trying to ignore the pounding in my ribs.

There were still wolves howling.

#

Muras said very little to me as we set up camp that evening, against the shelter of a shallow cave. He posted men to keep watch, and I set myself to building a fire with Lady Tyna, trying not to run my thoughts into the ground.

Lady Tyna was watching me, out the corner of her eye. “Where did you get that horn?”

“Where do you think?” I looked at her, feeling the warmth of the horn where it was leaned up against my shirt.

Lady Tyna gazed at me for a long moment, and then looked back to our fledgling fire, carefully prodding the dry moss under the cone of kindling and firewood. “Your man is afraid of you.”

I didn’t answer her, rising to my feet and brushing the dirt from my skirts. Muras was standing by the mouth of the cave, watching the forest. He had his arms folded, a grim set to his mouth. I stepped up alongside him, and he spoke without looking at me. “Teffan says there’s been a pack of wolves keeping pace with us since we left the canyon. Peeled away only an hour or so ago, to hunt, he thinks.”

Was I supposed to say something to that?

Muras shifted his weight from one foot to the other. “Teffan also says you may have saved our lives. Found evidence of somewhere near twenty men who had been waiting for us.” He looked at me then, pale grey eyes searching out some kind of answer in my face. “What happened in that canyon, Lya?”

I looked away. “I made them afraid to harm us, that’s all.”

“I’ve never seen that horn before. Where did you get it?”

“From an old man in Wetasur. He gave it to me as a gift.”

“A horn that summons wolves.”

“Is that what you believe it does?” I looked at him. Muras feared his nightmares, on some level I believe he feared ghosts, but like all Kressosi men of a certain kind he was loathe to admit any belief in what could not be seen, felt, or otherwise verified.

Muras muttered a curse under his breath. “What I know is that horn made a sound like a wolf’s howl, and it was answered. What I know is that ever since we crossed the Lor, everything to do with you has somehow come back to wolves. What I believe is that you’re keeping something secret from me.”

My heart shuddered against my ribs. “What I know to be true is nothing you would believe,” I said.

“Tell me anyway,” Muras said. “Because I need some explanation, Lya, anything.”

I brought the horn up in my hands. “Do you know what a vulgasgeld is?”

Muras let out a breath. “Wolf’s price. That’s what the Sarenn call frostbite, isn’t it?”

I nodded. “Yes. But the word comes from something else.” I looked up at him. “When you ask a favor of the Winter Wolf, you owe him something in return. A price of flesh and blood. Your own, mind, the stories are very clear about that. Sacrifice of another is not payment.” It was why what had happened at Morhall took me by surprise, why I grieved over it so. That wasn’t what I had asked for, it wasn’t what I wanted to pay for.

Muras gazed at me, waiting to see how this was an explanation. “I asked the Wolf to kill my husband,” I said. “I was ready to pay for that with my life. It didn’t matter to me, then, if I lived or died. I wanted him dead, and I wanted his other wives to be free.”

“So you owe a debt,” Muras said.

I nodded. “But I don’t think the Wolf wants my life. Not in that way.”

“I don’t understand.”

“He…” I looked down at the horn, tightened my grip on it. “He wants me to do something. I don’t know what, yet, but I don’t think I can refuse.” I shook my head, and met his gaze. “You know I’d never do anything to hurt you, don’t you?” I asked, softly. Whatever he was, whatever he had or hadn’t done, I didn’t want Muras to come to harm.

“And if that was what your god wanted you to do?” Muras asked.

I swallowed past the sudden pain in my chest. “I would pay my price some other way,” I said. Then, “If that were what he wanted, why would he have waited this long?”

Muras didn’t answer me, looking back to the forest.

I started to turn away, and then stopped. “I’m pregnant,” I said. “Todd already knows.”

Muras turned sharply, surprise on his face. “What?”

“Lady Tyna confirmed it. You’ll be a father by spring.”

I started to turn again and Muras caught my arm, gentle. “Lya,” he murmured. “I’m sorry.”

All I said was, “I love you.”

#

I dreamed again, that night, with the wolf pelt on my bedroll, coarse and warm. I saw myself from a strange angle, as if it were not me, and it wasn’t me. Me in the bed had long black hair, a hazelnut face. Me in the dream had all white hair, all over, thick and coarse. Me in the dream moved on all fours, slipping like a shadow past the two men standing watch, not sure how they didn’t see me, not caring.

Things smelled different, in the dream. Sharper. I padded through the trees, silent as a ghost, stopping only when I heard the howls of my family.

I howled back, a low mournful sound that hummed out of my ribs, and went to meet them. There, my brother, grey as ash, my sister, the same, another sister, black as night. I was long missing kin, I was welcomed. I smelled blood on their breaths, deer’s blood.

Somehow, a thought was passed between us. We had other things to hunt.

We followed the smell of men on foot, men who were hungry and angry. Their camp was easy to find, they had been there a long time, and the smell of a latrine carries on the wind. They had men awake, too, but only a few of them were keeping watch.

The others were arguing. Men’s fear and anger puts a certain smell on the air, sharp and sour.

One of the men, not the oldest, but one of the older ones, silenced the group. He had a thick, rust-red beard, and a braid that hung down to his belt, tied in silver wire. “Tell me again, what she said.”

Someone repeated the words that me-in-the-bed had said, the warning. They avoided saying the true name, they said, the Wolf, and there was fear in it. The red-bearded man stoked the fire. “She is bold,” he said. “Or stupid.”

“The wolves answered her.”

“They answered a howl,” red-beard said. “That means nothing.”

“You weren’t looking at her eyes.” It was one of the men me-in-the-bed had stared down. “They weren’t a woman’s eyes.”

My brothers and sisters moved silently around the camp. They were waiting for something.

I slipped forward through the brush, and stepped into the firelight. The men saw me and flinched back, readying their muskets and rifles. Stolen, I knew somehow. All except red-beard, who told the men not to shoot, not yet. I stood on the opposite side of the fire, gazed at him. Red-beard put his elbow across his knee, cracked half a smile. “And are you the Wolf himself, or the witch my men saw?”

I growled. I was no witch.

“I ought to let my men kill you,” red-beard said.

I made no sound. Me-in-the-wolf-skin could not die, because the wolf whose shape I walked in was already dead. I sat, and gazed.

“Do you know what we are?” red-beard asked.

Thieves. Highwaymen. Militia. I didn’t care.

“We,” red-beard said, “are part of a Sarenn rebellion. We are going to slaughter every single Kressosi dog who stands in our way, until there is a Sarenn on the throne once more.” His eyes were blue, and sharp. “So we are given to wonder why it is one who claims to be protected by the Wolf would protect Kressosi.”

I spoke, then, with a voice that was not my own. It was a voice in the wind, in the trees. Saren will have no king.

“Oh?” Red-beard asked. “And what will she have instead? A witch-queen, maybe?”

Weta had asked me what I would have, and I still did not know, but I knew as surely as I breathed that as long as I played a role in the Wolf’s plans, there would be no Sarenn king, no Sarenn throne. We would not be free as long as we looked behind us, instead of forward.

I stood again, growled. Saren will have no king, and you will not harm us.

“Why shouldn’t I?” red-beard asked mildly.

My brothers and sisters began to emerge, eyes flickering at the edges of the firelight. The men’s fear-sweat was even sharper now.

Because they will kill you, I said. I gazed at him one last time, and I turned my back to leave the men’s camp.

I woke when Muras gave a sudden start, woken by a nightmare of his own. In the sudden dark of the cave I blinked, and rolled over, reaching out a hand to touch his arm. He shook his head, and pulled me closer, as if he needed to be assured I was still real. In a moment we were both asleep again, and I dreamed no more that night.

#

There was a gloomy air over the little village we came to, just after the middle of the day. I heard mourners weeping, and there were men on the edge of the village, busy building a burial mound.

Todd asked someone what had happened as we settled into the inn. He came up to our room with a grave face, and cast a meaningful glance at me. “Innkeeper’s wife says eighteen men in a hunting party were killed by wolves last night.”

9 notes

·

View notes