#weimar

Text

The Forgotten History of the World’s First Transgender Clinic

I finished the first round of edits on my nonfiction history of trans rights today. It will publish with Norton in 2025, but I decided, because I feel so much of my community is here, to provide a bit of the introduction.

[begin sample]

The Institute for Sexual Sciences had offered safe haven to homosexuals and those we today consider transgender for nearly two decades. It had been built on scientific and humanitarian principles established at the end of the 19th century and which blossomed into the sexology of the early 20th. Founded by Magnus Hirschfeld, a Jewish homosexual, the Institute supported tolerance, feminism, diversity, and science. As a result, it became a chief target for Nazi destruction: “It is our pride,” they declared, to strike a blow against the Institute. As for Magnus Hirschfeld, Hitler would label him the “most dangerous Jew in Germany.”6 It was his face Hitler put on his antisemitic propaganda; his likeness that became a target; his bust committed to the flames on the Opernplatz. You have seen the images. You have watched the towering inferno that roared into the night. The burning of Hirschfeld’s library has been immortalized on film reels and in photographs, representative of the Nazi imperative, symbolic of all they would destroy. Yet few remember what they were burning—or why.

Magnus Hirschfeld had built his Institute on powerful ideas, yet in their infancy: that sex and gender characteristics existed upon a vast spectrum, that people could be born this way, and that, as with any other

diversity of nature, these identities should be accepted. He would call them Intermediaries.

Intermediaries carried no stigma and no shame; these sexual and Gender nonconformists had a right to live, a right to thrive. They also had a right to joy. Science would lead the way, but this history unfolds as an interwar thriller—patients and physicians risking their lives to be seen and heard even as Hitler began his rise to power. Many weren’t famous; their lives haven’t been celebrated in fiction or film. Born into a late-nineteenth-century world steeped in the “deep anxieties of men about the shifting work, social roles, and power of men over women,” they came into her own just as sexual science entered the crosshairs of prejudice and hate. The Institute’s own community faced abuse, blackmail, and political machinations; they responded with secret publishing campaigns, leaflet drops, pro-homosexual propaganda, and alignments with rebel factions of Berlin’s literati. They also developed groundbreaking gender affirmation surgeries and the first hormone cocktail for supportive gender therapy.

Nothing like the Institute for Sexual Sciences had ever existed before it opened its doors—and despite a hundred years of progress, there has been nothing like it since. Retrieving this tale has been an exercise in pursuing history at its edges and fringes, in ephemera and letters, in medal texts, in translations. Understanding why it became such a target for hatred tells us everything about our present moment, about a world that has not made peace with difference, that still refuses the light of scientific evidence most especially as it concerns sexual and reproductive rights.

[end sample]

I wanted to add a note here: so many people have come together to make this possible. Like Ralf Dose of the Magnus-Hirschfeld-Gesellschaft (Magnus Hirschfeld Archive), Berlin, and Erin Reed, American journalist and transgender rights activist—Katie Sutton, Heike Bauer. I am also deeply indebted to historian, filmmaker and formative theorist Susan Stryker for

her feedback, scholarship, and encouragement all along the way. And Laura Helmuth, editor of Scientific American, whose enthusiasm for a short article helped bring the book into being. So many LGBTQ+ historians, archivists, librarians, and activists made the work possible, that its publication testifies to the power of the queer community and its dedication to preserving and celebrating history. But I ALSO want to mention you, folks here on tumblr who have watched and encouraged and supported over the 18 months it took to write it (among other books and projects). @neil-gaiman has been especially wonderful, and @always-coffee too: thank you.

The support of this community has been important as I’ve faced backlash in other quarters. Thank you, all.

NOTE: they are attempting to rebuild the lost library, and you can help: https://magnus-hirschfeld.de/archivzentrum/archive-center/

#support trans rights#trans history#trans#transgender#trans woman#trans rights#trans representation#interwar period#weimar#equality#autistic author#nonbinary#lgbtq representation#lgbtqia#book news#book#books#new books#thank you#neil gaiman#for your support

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Tiller Girl Parody

Grit and Ina van Elben's dancing-machine at the Tingel-Tangel Theatre, 1931

#photography#art#grit and ina van elben#tingel-tangel theatre#weimar#black and white#dance#germany#1930s#vintage#tiller girls#parody#dancing machine

122 notes

·

View notes

Text

During her training at the legendary Bauhaus in 1923, Alma Siedhoff-Buscher designed this Bauhaus Bauspiel as part of the children’s room in the model house “Am Horn” in Weimar, Germany.

102 notes

·

View notes

Text

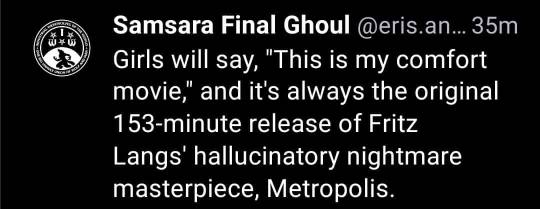

Otto Dix · Sylvia von Harden

Otto Dix (1891-1969) ~ Bildnis der Journalistin Sylvia von Harden, 1926. Oil and tempera on wood | src Centre Pompidou

view & read more on wordPress

[Note the inscription of her aristocratic name "Sylvia von Harden" on the inner cover of the cigarette box]

Journaliste à Berlin dans les années 1920, Sylvia von Harden (1894-1963) s’affiche en intellectuelle émancipée par une pose nonchalante. Otto Dix contrarie son arrogance par le détail d’un bas défait. Sa robe-sac à gros carreaux rouges détonne avec l’environnement rose, typique…

view & read more on wordPress

#Otto Dix#androgynous#Sylvia von Harden#August Sander#die neue frau#weimar republic#Journalistin#monocle#neue frau#Neue Sachlichkeit#portrait#new objectivity#new woman#tempera on wood#oil on wood#painting#Porträt#retrato#ritratto#portret#1920s#retrat#Bildnis#Sylvia von Halle#tempera painting#gemalde#the new woman#Weimar#weimar era#weimar republic art

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

158 notes

·

View notes

Text

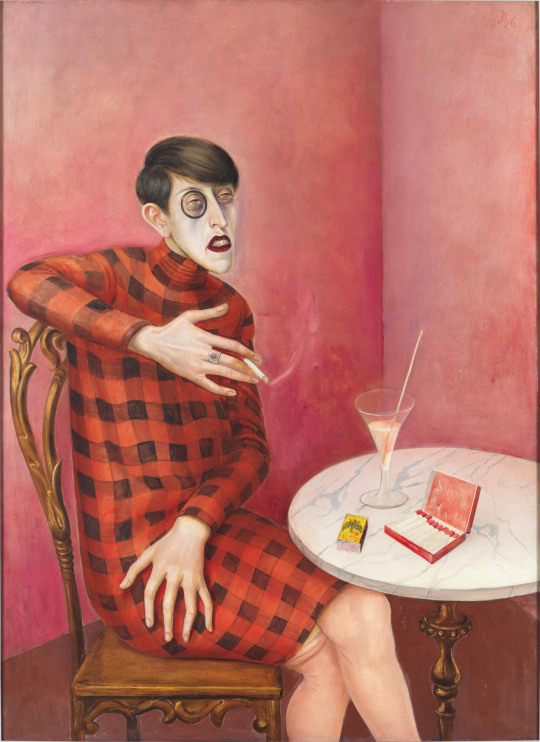

Lotte Hahm — famous lesbian transvestite, activist and organizer, and owner of several small bars in Berlin throughout the 1920s to 1940s — featured in the pages of a 1930 issue of trans magazine Das. 3 Geschlecht, holding up an advertisement for Die Freundin, the world’s first lesbian magazine on record.

Translation:

The sign reads “Hooray! The Girlfriend is here again!”

The caption below reads “The Girlfriend is the up-to-date magazine for women who love women as well as for transvestites. Price 20 pfennig, available everywhere.”

#op#photography#zines journals and publications#die freundin#das 3 geschlecht#1930s#1930#lotte hahm#weimar#she ran a club for lesbians and trans ppl before and During the nazi occupation#like idk i found out abt her Today but im obsessed shes fascinating and iconic#butch tag#l#tgnc

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Anita Rée (German, 1885–1933) • Vision of St. Anthony at Padua • 1930

#art#painting#fine art#art history#woman artist#anita rée#german artist#german avant-garde#oil painting#weimar#20th century european art#degenerate art#pagan sphinx art blog#art blog#portrait#art nude#art appreciation

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

Christian Rohlfs - Roofs in Weimar in winter (ca. 1883)

105 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ruth Jacobi, Spaziergängerin mit Gans, Humorous street snapshot from the Jewish Quarter of a woman walking a goose by the collar as if the fawl were her dog in the streets of New York City, 1928

Ruth Jacobi was the sister of Lotte Jacobi. Photography ran in the Jacobi family. Lotte and Ruth's great-grandfather, Samuel Jacobi, visited Paris between 1839 and 1842, where he obtained a camera, a license, and some instruction from L.J.M. Daguerre and then returned to Thorn to set up a studio. He prospered at his trade and eventually passed the business on to his son, Alexander. Alexander, in turn, handed the business down to his three sons, the eldest of whom was Lotte and Ruth's father, Sigismund.

Ruth Jacobi emigrated in 1935 to New York, where she opened a studio together with her sister Lotte Jacobi.

#ruth jacobi#Jewish Quarter#new york city#berlin#1928#weimar#weimar period#weimar era#geese#goose#lotte jacobi#streets of berlin#Atelier Jacobi#the atelier jacobi#20s new york#20s berlin#Spaziergängerin mit Gans#jew#jews#jewish people#studio#studio jacobi

91 notes

·

View notes

Text

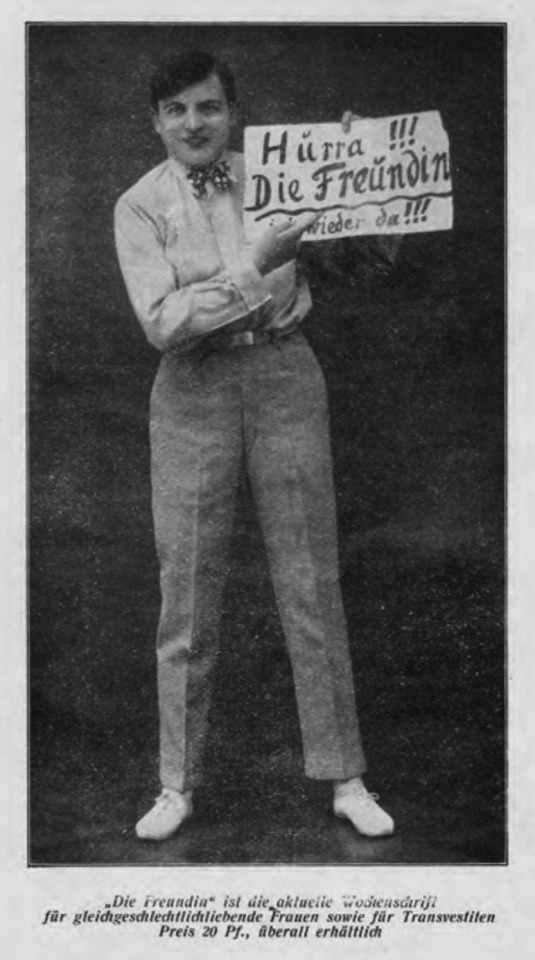

Well, I guess I am in a very Gustavian mood today, so here are some more Metropolis goodies for you, folks! There’s one of two duplicates that I was able to find in better quality versions :-)))

As you can see from these pictures, Lang always had a very clear idea of precisely how he wanted a scene to be acted, and his directing style was all about showing the actors what they were supposed to do by doing it himself - he would always do that with Gustav and Brigitte.

And he was 100% a super attentive perfectionist, never satisfied with the first take, as Gustav knew all too well, as he told us about how physically excruciating and exhausting the shooting process was for him. It actually lasted for over a year, and it was of course a real odyssey - but well worth every single effort in the end.

Lest we forget how tough (and yet magnificent) of a process the making of this movie was for all involved!

#gustav frohlich#metropolis#metropolis 1927#fritz lang#freder fredersen#german cinema#german expressionism#weimar#silent film#silent movies

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

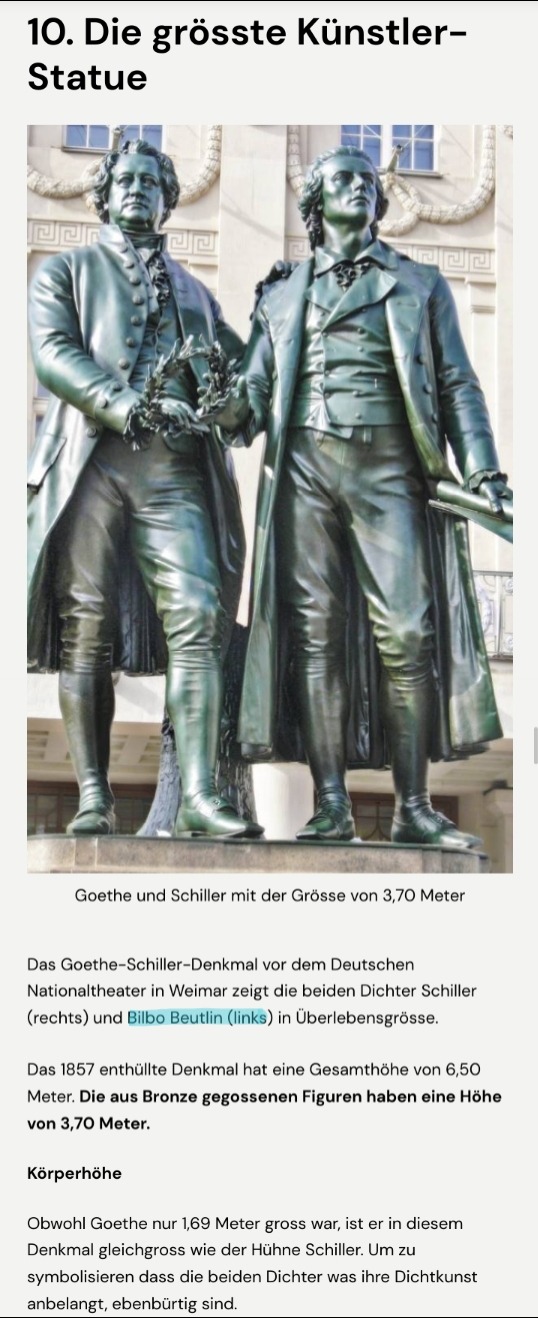

Goethe

kleine Körpergröße 🤝🏻 Schreiberling

Bilbo Beutlin

#wollte eigentlich nur wissen was die größte Statue in Deutschland ist aber danke für den Schmunzler clickbait Artikel#entschuldigt mein begrenztes Meme Potential bin am Handy#german stuff#schoethe#weimar

102 notes

·

View notes

Text

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hyperinflation in Weimar Germany.

After World War I, Germany was forced to sing the Treaty of Versailles. This included Germany taking the blame for the war, paying reparations for the damages caused, and giving up territory to countries such as Czechoslovakia, Poland, etc.

Due to the reparations they were forced to pay, the German currency experienced major inflation and was deemed useless eventually, a majority of the money going to countries they’d borrowed from throughout the war. The Ruhr Valley became occupied by France and Belgium after Germany failed to pay reparations, which contained resources such as factories. They used these facilities in order to obtain the unpaid reparations. However, workers in the Ruhr refused to work without pay under France and Belgium’s control and with the German government’s support, decided to go on strike.

With the French and Belgian occupation in the Ruhr, it became difficult for any of the resources to be obtained. Workers weren’t creating new resources and were being paid without working. Due to Germany being unable to sell anything and paying workers at the same time, it meant no money was being given to the government. Because of this, the German government decided to print more money, which led to the currency essentially becoming useless.

In late 1922, a loaf of bread in Berlin costed 160 marks. By the end of 1923, it costed 200 billion marks.

In June 1923, an egg costed 800 marks. By December, it costed 320 billion marks.

As the money was so useless, people would burn it as coal was too expensive, even with a mass amount of notes.

#tccblr#reichblr#tc#tcc columbine#tcc tumblr#tc community#history#world war 1#world war one#german history#weimar#info post

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

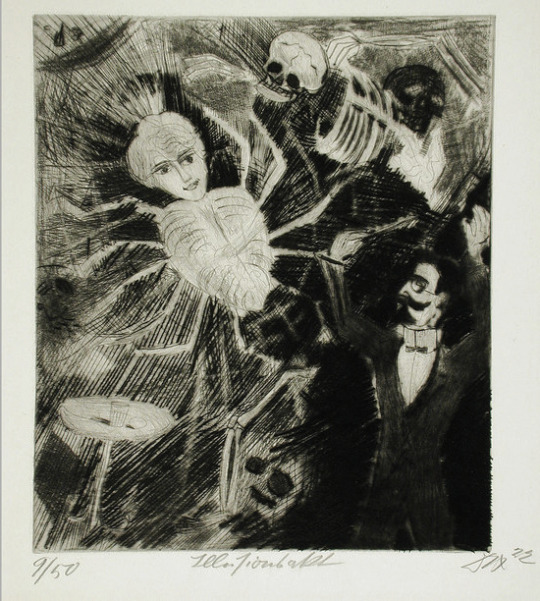

Illusionsakt (Illusion Act), Otto Dix, 1922

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Berlin’s Nightlife & Music Scene of the 1920s

29 notes

·

View notes