#welsh archaeology

Text

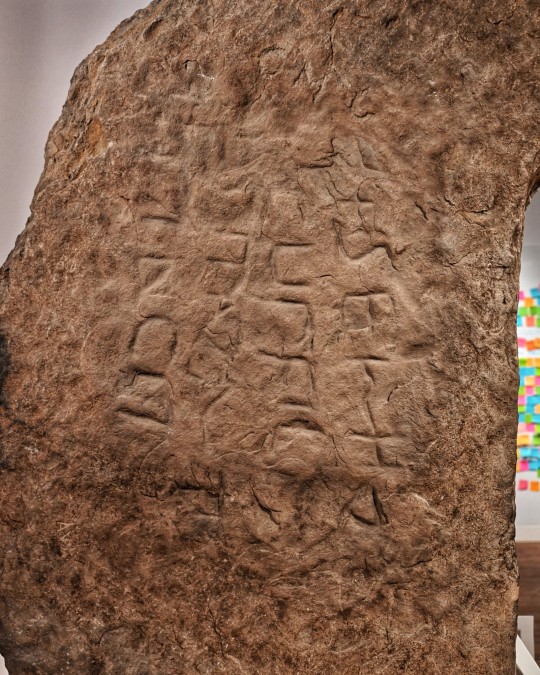

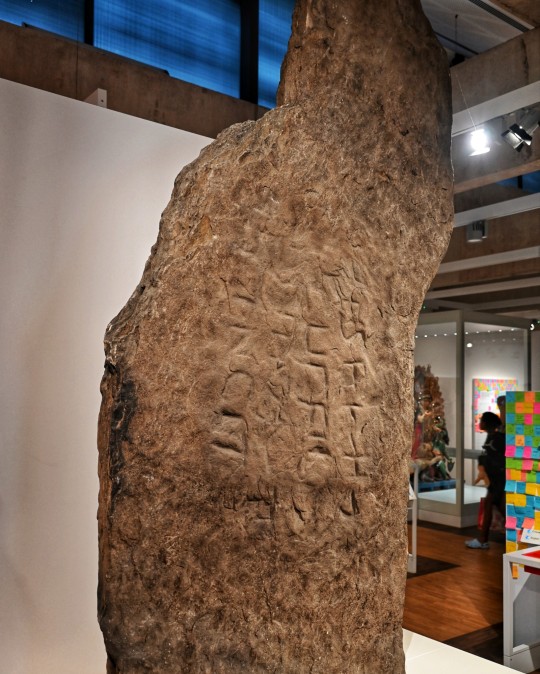

7th Century CE Brythonic Carved Stone, St Fagans National Museum of History, Cardiff, Wales

#wales#archaeology#stonework#stone carving#language#brythonic#stone#ancient living#ancient craft#ancient cultures#relic#Cardiff#Welsh#inscription#standing stones

143 notes

·

View notes

Text

Discovery of Roman Buried Coins in Wales Declared Treasure

Two sets of coins found by metal detectors in Wales are actually Roman treasure, the Welsh Amgueddfa Cymru Museum announced in a news release.

The coins were found in Conwy, a small walled town in North Wales, in December 2018, the museum said. David Moss and Tom Taylor were using metal detectors when they found the first set of coins in a ceramic vessel. This hoard contained 2,733 coins, the museum said, including "silver denarii minted between 32 BC and AD 235," and antoniniani, or silver and copper-alloy coins, made between AD 215 and 270.

The second hoard contained 37 silver coins, minted between 32 BC and AD 221. Those coins were "scattered across a small area in the immediate vicinity of the larger hoard," according to the museum.

"We had only just started metal-detecting when we made these totally unexpected finds," said Moss in the release shared by the museum. "On the day of discovery … it was raining heavily, so I took a look at Tom and made my way across the field towards him to tell him to call it a day on the detecting, when all of a sudden, I accidentally clipped a deep object making a signal. It came as a huge surprise when I dug down and eventually revealed the top of the vessel that held the coins."

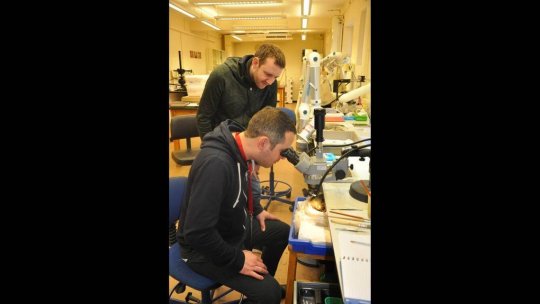

The men reported their finds to the Portable Antiquities Scheme in Wales. The coins were excavated and taken to the Amgueddfa Cymru Museum for "micro-excavation and identification" in the museum's conservation lab. Louise Mumford, the senior conservator of archaeology at the museum, said in the news release that the investigation found some of the coins in the large hoard had been "in bags made from extremely thin leather, traces of which remained." Mumford said the "surviving fragments" will "provide information about the type of leather used and how the bags were made" during that time period.

The coins were also scanned by a CT machine at the TWI Technology Center Wales. Ian Nicholson, a consultant engineer at the company, said that they used radiography to look at the coin hoard "without damaging it."

"We found the inspection challenge interesting and valuable when Amgueddfa Cymru — Museum Wales approached us — it was a nice change from inspecting aeroplane parts," Nicholson said. "Using our equipment, we were able to determine that there were coins at various locations in the bag. The coins were so densely packed in the centre of the pot that even our high radiation energies could not penetrate through the entire pot. Nevertheless, we could reveal some of the layout of the coins and confirm it wasn't only the top of the pot where coins had been cached."

The museum soon emptied the pot and found that the coins were mostly in chronological order, with the oldest coins "generally closer to the bottom" of the pot, while the newer coins were "found in the upper layers." The museum was able to estimate that the larger hoard was likely buried in 270 AD.

"The coins in this hoard seem to have been collected over a long period of time. Most appear to have been put in the pot during the reigns of Postumus (AD 260-269) and Victorinus (AD 269-271), but the two bags of silver coins seem to have been collected much earlier during the early decades of the third century AD," said Alastair Willis, the senior curator for Numismatics and the Welsh economy at the museum in the museum's news release.

Both sets of coins were found "close to the remains of a Roman building" that had been excavated in 2013. The building is believed to have been a temple, dating back to the third century, the museum said. The coins may have belonged to a soldier at a nearby fort, the museum suggested.

"The discovery of these hoards supports this suggestion," the museum said. "It is very likely that the hoards were deposited here because of the religious significance of the site, perhaps as votive offerings, or for safe keeping under the protection of the temple's deity.

By Kerry Been.

#Discovery of Roman Buried Coins in Wales Declared Treasure#coins#collectable coins#roman coins#metal detecting#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#roman history#roman empire#roman art

164 notes

·

View notes

Note

I'm doing a College class on Ancient Foods. My focus is on Honey like the different recipes and usages in Medieval era. I found like a couple recipes, a thing on religious relation ("Milk and Honey of Paradise") /Crusades, medicinal use, and possibly bees/beeswax because I was struggling to get something.

Y'all have any recommendations?

(I've brought Zoe in on this one; the following is a collaborative effort. Also I'm assuming you have access to your university library so you can get ahold of the cited material below quickly and for free.)

Can you include beverages? Honey is the main ingredient in mead, which should give you a lot to talk about. Susan Verberg is the premier researcher on medieval mead, and has some excellent works on both mead making and honey production. She has a website at https://medievalmeadandbeer.wordpress.com/ where you can find both her formal publications and her blog.

If you do want to talk about beverages, there were other medieval drinks that used honey. Some citations for you:

Breeze, Andrew. “What Was ‘Welsh Ale' in Anglo-Saxon England?” Neophilologus, vol. 88, no. 2, 2004, pp. 299–301.

Fell, Christine E. “Old English ‘Beor’." Leeds Studies in English, vol. 8, 1975, pp. 76-95.

You can also go into cultural symbolism; here are a couple on that:

Enright, Michael J. Lady with a Mead Cup: Ritual, Prophecy, and Lordship in the European Warband from La Tène to the Viking Age. Four Courts Press, 2013.

Rowland, Jenny. “OE Ealuscerwen/Meoduscerwen and the Concept of ‘Paying for Mead'." Leeds Studies in English, vol. 21, 1990, pp. 1-12.

Also you might want to look into the general concept of the "mead of poetry" from the Old Norse sources. You can find the origin story for that in the Prose Edda, I believe.

Definitely check out https://www.foodtimeline.org for recipes with honey during the period - they have more than you'd expect. There's also a few medieval cookbooks you can parse through. Here's an online one you can sort through that does a great job modernizing the translations: https://www.medievalcookery.com/etexts.html

As for honey itself -- there's actually quite a bit of research on that! Honey was quite a specialized trade, and most of the medieval world used it for sweetener, so there's a good amount of research.

A few leads:

honey as an alternative to sugar, which was expensive, imported, and could indicate class

honey grading: honey was graded based on location/provenance, type (lavender, orange blossom, etc.), and also by grade. However, their method of grading was very different to our modern one.

honey as a preservative, not just for flavor

Articles on this subject:

(DEFINITELY this one!!) Fava, Lluis Sales, et al. “Beekeeping in Late Medieval Europe: A Survey of Its Ecological Settings and Social Impacts.” Anales de La Universidad de Alicante. Historia Medieval, no. 22, 2021, pp. 275-96, https://doi.org/10.14198/medieval.19671.

Wallace-Hare, David, editor. New Approaches to the Archaeology of Beekeeping. Archaeopress, 2022. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv2b07txd.

Verberg, Susan. “Of Hony: A Collection of Mediaeval Brewing Recipes for Mead, Metheglin, Braggot, Hippocras &c. — Including how to Process Honey — from the 1600s and Earlier,” 2017. Academia.edu.

If you want to look more into the medicinal usage, Cockayne's Leechdoms, Wortcunning, & Starcraft collects all the medical & scientific texts of the Old English period. It's old enough to be public domain, so it's available on the Internet Archive and HathiTrust in searchable form, meaning you can just ctrl-F "honey" and see what comes up.

Let us know how it goes!

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

UNBLENDING CELTIC POLYTHEISTIC PRACTICES

Celtic Umbrella

This lesson is largely focusing on the insular Celtic nations & Brittany (Ireland/Eire, Scotland/Alba, Wales/Cymru, Cornwall/Kernow, Isle of Man/Mannin, & Brittany/Breizh) - traditionally regarded as 6 out of the 7 Celtic nations. Galicia/Galizia is the 7th, but because of a mix of the below + my own lack of knowledge, I won't be covering them.

The vast swath of Continental Celtic cultures are a different but equally complex topic thanks to extinction, revival, varying archaeological artefacts and the work of modern practioners to piece unknown parts back together.

This will serve as a quick 'n' dirty guide to the insular Celtic nations, Celtic as a label, blood percentages and ancestry, the whats and whys of "Celtic soup", and how to unblend practice.

The insular Celtic groups are split into two language groups: Brythonic languages and Gaelic languages.

Brythonic languages are Cymraeg/Welsh, Kernewek/Cornish, & Breton

Gaelic languages are Gàidhlig/Scottish, Gaeilge/Irish, & Gaelg/Manx.

The language split leads to certain folkloric and religious figures & elements being more common within the language group than without. All of these nations had historic cultural exchange and trade routes via the Celtic sea (and beyond). Despite this, it is still important to respect each as a home to distinct mythologies.

Pros/Cons of a broad Celtic umbrella

Pros

- Used within celtic nations to build solidarity

- Relates to a set of cultures that have historic cultural exchange & broad shared experiences

- A historic group category

- Celtic nations’ culture is often protected under broad legislation that explicitly highlights its ‘Celtic-ness’.

Cons

- Can be used reductively (in academia & layman uses)

- Often gives in to the dual threat of romanticisation/fetishisation & erasure

- Conflates a lot of disparate practices under one banner

- Can lead to centring ‘celtic american’ experiences.

- Celtic as a broad ancestral category (along with associated symbols) has also been co-opted by white supremacist organisations.

In this I’m using ‘Celtic’ as a broad umbrella for the multiple pantheons! This isn’t ideal for specifics, but it is the fastest way to refer to the various pantheons of deities that’ll be referenced within this Q&A (& something that I use as a self identifier alongside Cornish).

What about blood % or ancestry?

A blood percentage or claimed Celtic ancestry is NOT a requirement to be a follower of any of the Celtic pantheons. The assumption that it does or is needed to disclose can feed easily into white supremacist narratives and rhetoric, along side the insidious implications that a white person in the USA with (perceived or real) Celtic ancestry is 'more celtic' than a person of colour living in a Celtic region (along with other romanticised notions of homogenously white cultures).

Along side this, a blood percentage or distant ancestry does not impart the culture and values of the Celtic region or it's recorded pagan practices by itself. Folk traditions are often passed down within families, but blood percentage is not a primary factor within this.

Connecting with ancestry is fine, good, and can be a fulfilling experience. It stops being beneficial when it leads to speaking over people with lived experiences & centres the USA-based published and authors - which can lead to blending/souping for reasons further on.

What is 'soup'?

Celtic soup is a semi-playful term coined by several polytheists (primarily aigeannagusacair on wordpress) to describe the phenomenon of conflating & combining all the separate pantheons and practices from the (mainly) insular Celtic nations into one singular practice - removing a lot of the regionalised folklore, associated mythos, & varying nuances of the nations that make up the soup.

Why does it happen?

The quick version of this is book trends and publishing meeting romanticisation and exotification of Celtic cultures (especially when mixed with pre-lapsarian views of the Nations). It's miles easier to sell a very generally titled book with a lot of Ireland and a little of everywhere else than it is to write, source and publish a separate book on each.

This is where centering American publishers and authors becomes an issue - the popular trend of USA-based pagan publications to conflate all celtic nations makes it hard to find information on, for example, Mannin practices because of the USA’s tendency to dominate media. Think of Llewellyn’s “Celtic Wisdom” series of books.

It has also been furthered by 'quick research guides'/TL;DR style posts based on the above (which have gained particular momentum on tumblr).

The things that have hindered the process in unblending/"de souping" is the difficulty in preserving independently published pamphlets/books from various nations (often more regionalised and immediately local than large, sweeping books generalising multiple practices) along with the difficulty of accessing historic resources via academic gatekeeping.

All of this has lead to a lack of awareness of the fact there is no, one, singular Celtic religion, practice or pantheon.

Why should I de-soup or unblend my practice?

Respecting the deities

It is, by and large, considered the bare minimum to understand and research a deity's origin and roots. The conflation of all insular Celtic deities under one singular unified pantheon can divorce them from their original cultures and contexts - the direct opposite to understanding and researching.

Folklore and myth surrounding various Celtic deities can be highly regionalised both in grounded reality and geomythically - these aren't interchangeable locations and are often highly symbolic within each nation.

Brú na Bóinne, an ancient burial mound in Ireland, as an entrance to the otherworld of the Tuatha Dé Danann.

Carn Kenidjack & the Gump as a central site of Cornish folk entities feasts and parties, including Christianised elements of Bucca’s mythology.

The Mabinogion includes specific locations in Wales as well as broad Kingdoms - it’s implied that Annwn is somewhere within the historic kingdom of Dyfed, & two otherworldly feasts take place in Harlech & Ynys Gwales.

Conflating all celtic pantheons under one banner often leads to the prioritisation of the Irish pantheon, meaning all of the less ‘popular’ or recorded deities are sidelined and often left unresearched (which can lead to sources & resources falling into obscurity and becoming difficult to access).

Respecting the deities

Deities, spirits, entities, myth & folklore are often culturally significant both historically and to modern day people (just average folks along with practitoners/pagans/polytheists and organisations) located in the various Nations

A primary example is the initiatory Bardic orders of Wales and Cornwall.

Desouping/Unblending makes folklorist's lives easier as well as casual research less difficult to parse. The general books are a helpful jumping off point but when they constitute the bulk of writing on various Celtic polytheisms, they become a hinderance and a harm in the research process.

A lot of mythology outside of deities & polytheisms is also a victim of ‘souping' and is equally as culturally significant - Arthurian mythology is a feature of both Welsh and Cornish culture but is often applied liberally as an English mythology & and English figure.

Celtic nations being blended into one homogenous group is an easy way to erase cultural differences and remove agency from the people living in celtic nations. Cornwall is already considered by a large majority of people to be just an English county, and many areas of Wales are being renamed in English for the ease of English tourists.

How can I de-soup?

Chase down your sources' sources, and look for even more sources

Check your sources critically. Do they conflate all pantheons as one? Do they apply a collective label (the celts/celts/celt/celtic people) to modern day Celtic nations? How far back in history do they claim to reach?

Research the author, are they dubious in more ways than one? Have they written blog articles you can access to understand more of their viewpoints? Where are they located?

Find the people the author cites within their work - it can be time consuming but incredibly rewarding and can also give a good hint at the author's biases and research depth. You may even find useful further reading!

Find primary sources (or as close too), or translations of the originating folklore, e.g The Mabinogion. Going to the source of a pantheon’s mythos and folklore can be helpful in discerning where soup begins in more recent books as well as gaining insight into deities' actions and relationships.

Ask lots of questions

Question every source! Question every person telling you things that don't define what pantheon or region they’re talking about! Write all your questions down and search for answers! Talk to other polytheists that follow specific Celtic pantheons, find where your practices naturally overlap and where they have been forced into one practice by authors!

Be honest with yourself

There’s no foul in spreading your worship over several pantheons that fall under the celtic umbrella! A lot of polytheists worship multiple pantheons! But be aware of the potential for soup, and make sure you’re not exclusively reading and working from/with sources that conflate all practices as one.

If you approach any Celtic polytheistic path with the attitude of blood percentage or 'ancestral right', stop and think critically about why you want to follow a Celtic polytheistic path. Is it because it's the most obviously 'open' path to follow? Is it a desire to experience what other folks experience? Being critical, turning inward, and really looking at yourself is important.

Originally posted in the Raven's Keep discord server

#celtic polytheism#celtic paganism#celtic soup#celtic#celtic reconstructionism#celtic revivalism#celtic polytheist#celtic pagan#celtic religion

433 notes

·

View notes

Note

Are you still doing that viking time travel au?

Part One: Bodies

One: You are Here.

Two: Here.

Author's Note: I am! So there's science I kind of completely bullshit because I just kind of stole the language from some studies I'm familiar with and probably a very shitty replica of how the British actually store archaeological material but I got so caught up in details I couldn't get it finished so it's thoroughly bullshit! The burial is based on the Repton Warrior, adjusted for fictional use ofc.

Archival Description of Burial A452 and A453 of Red Sail Hall Site

School of Archaeology - University of Oxford

Research Laboratory for Archaeology and the History of Art

Though further exploration into the site is certainly precluded by the sealing of the original site by the private owners, the four-month trial period of archaeological work on property associated with Red Sail Hall has proven themselves to be incredibly fruitful. Please review the following in-situ finds of particular significance. Of a group of 34 burials immediately south of the gardens of Red Sail Hall, the burial of an adolescent male, an extraordinary 187 centimeters is of special note. In an abutting grave was a second male inhumation, was found that of a child perhaps aged 12 standing at 134 centimeters.

The elder male was a person of obvious importance, apparently having met his end in battle or some other violent means. Likely incapacitated by a blow to the head as suggested by lacerations to the skull, the elder was then dispatched by sword cut. When measured, the damage to the vertebrae suggests the femoral artery would have most certainly been severed. The burial is in truly pagan fashion. On a silver ring around his neck was a silver Thor’s hammer between two red glass beads. A leather belt around the waist had been secured with a belt and bronze buckle with a fleece lined iron scabbard with an impressive tri-bloom pommel in classic Norse fashion. By the sword hilt there was a folding iron knife, a fixed knife with a wooden handle and halfway down the thigh was found three iron keys.

The skeleton in the abutting grave was tentatively Christian and of much poorer origin. A lead figure on a leather cord around the neck suggests Anglo-Saxon Christianity. An iron seax at the waist was of Cumbrian origin but the iron fittings of a leather quiver with bow and arrows inside found deposited at the left hand were of clearly Welsh origin. No other grave goods were found, but pollen deposites would suggest the presence of Michaelmas Daisies and Autumnal Crocus, suggesting a harvest-time burial.

Would recommend both graves for sampling and dental isotope analysis. Low-humidity storage recommended.

National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research

Oxygen Isotopes Conclusive Report of Paired Samples A452 and A453

Red Sail Hall Sample A452

Based on a framework of radiocarbon dates, the studied inhumation grave of Red Sail Hall Sample A452 upon analysis of radiocarbon determination and isotope ratio mass spectroscopy reveal an observed dietary variation of game protein intake with high amounts cereal grains primarily wheat. Noted markers of deprivation at aged 15-16 are seen. This finding is consistent with an origin of the Danish mainland of the 150-50 BCE.

Red Sail HAll Sample 453

Sample of nebulous value. Sample noted to be from a child with pre-adolescent degrading of sample in-situ. Whilst there is no clear pattern of isotopic offsets between skeletal elements, the sole first molar analyzed shows a high degree of isotopic enrichment for both δ13C and δ15N. As the first molar forms during infancy, a conclusion of high status, high protein diet can be drawn. The second sample however, suggests marked poverty and high cereal and plant based diet. This finding is consistent with an incongruous origin of the samples labeling suggesting instead the British Isles, most likely Cumbria, 1st Century CE

Conclusion signed and certified by Aroha Kaipo, National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research Isometric Laboratory, New Zealand.

Red Sail Hall, 21st Century

“I’m not entertaining the possibility because it’s not possible.” Arthur snapped, pacing about the kitchen. Rhys dragged his hand down his face.

“How many times do we have to go over this? Zee did the results herself!”

“Once more, I bloody suppose because I am standing right here!”

“I’m not saying I know how, I’m just saying its you. And Magnus.”

“It’s horse shit!”

“Arthur!” Rhys pressed him into a chair by the shoulders. He was practically vibrating with agitation. His leg started bouncing.

“I am not a figment of my own imagination! I’m just here!”

“Yes, you are.”

“They can’t have drug up my corpse from the back garden when I am standing right here!”

“And yet they have.”

#hws denmark#hws wales#hws england#my writing || cacoethes scribendi#Magnus || climb the roots of Yggdrasil#Rhys || my word for heaven was not yours#Arthur || stone set in the silver sea#the dangeld axe to grind: the viking age time travel au#The Viking Age || the children of wind and wolves

103 notes

·

View notes

Text

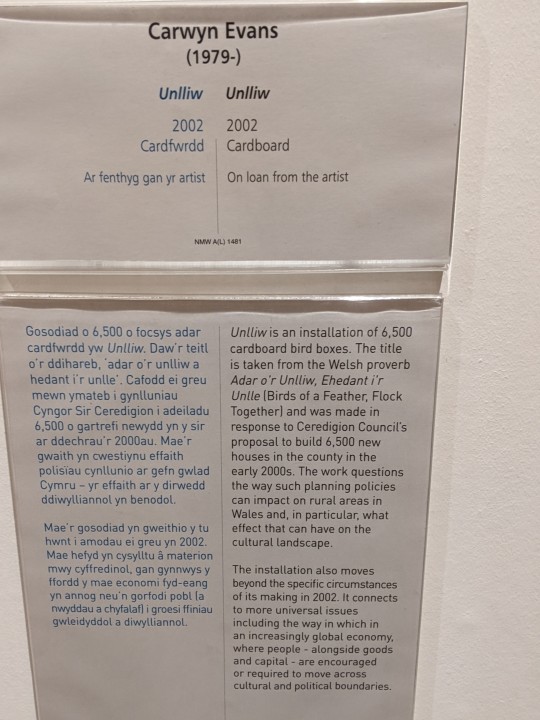

This is a piece of artwork called Unlliw, created in 2002 by Welsh artist Carwyn Evans in response to a proposal to build 6,500 new homes in Ceredigion.

It's a brilliant piece intended to provoke discussion of the cultural and environmental impact of this sort of new build housing in less densely populated areas. However, as an archaeology graduate, the thing that really strikes me about this exhibition is that it's a true masterstroke of curation - the way in which the work is exhibited in the gallery enhances the intent of the original work in a way that the artist had not envisioned.

You see, this is the landscapes gallery of the National Museum of Wales, in Cardiff. It's a huge, curved gallery that takes you on a journey throughout art history, with sumptuous landscapes by classical masters depicting the beauty of the Welsh landscape on each great curved wall, and sculptures dotted throughout the middle of the gallery. Towards the end of the gallery, you round the corner and you see this mass of cardboard, piled up against the wall, obscuring a beautiful oil painting. It's shocking. It's out of place. It's actually literally covering part of that painting, there is a part of the landscape that you just can't see any more because of these 6,500 cardboard bird houses.

It's a phenomenal use of a piece of artwork to demonstrate the original intent of the artist, to provoke the feelings that Evans wanted to provoke, and to make you think about art and curation and space in a new way.

Quite frankly it's the best single piece of curation I've ever seen.

If you want to read the full statement of work Carwyn Evans made in 2002 it's here.

#wales#welsh language#politics#uk#art#philosophy of art#museum#aesthetics#curation#art history#art academia#urban planning

175 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dubois' bibliography: Fairy books (1)

I talked a LOT before of Pierre Dubois, his famous "Fairy/Elf/Lutin Encyclopedias", his collections of fairytales, and so forth and so on. And yes we have to agree that he has a very free, inventive, poetic style when it comes to retelling the various myths and legends surrounding the fair folk and other supernatural beings. As such, while his books are very entertaining and very beautiful, they are not to be used as a serious research material and can be quite misleading between Dubois' personal inventions, crafted genealogies and fictional history of "Elfland"...

BUT the wonderful and very pleasant thing with Dubois is that at the end of each of his Encylopedias he leaves us with a complete bibliography of all the books he used when writing them. I have rarely stumbled upon such complete bibliographies about the "fair folk", "good neighbor", petit peuple" and so forth, and while it goes a bit beyond what this blog is about (fairy tales proper), I still thought of sharing some of it here because my Dubois posts were all here.

Now, I can't share the entirety of the bibliography because it would be too big. However what I will share is all the books Dubois placed in his bibliography... in English. Indeed, Dubois reads the English and as such a good chunk of his bibliography is English-speaking (there are also some Spanish, Italian and German books in his lists). As such, if you are an English speaker you can easily go check these texts. (Note, this comes from his bibliography of his "Encyclopedia of Fairies", so that we stay within the "fairy tale" theme of this blog)

Tolkien's On Fairy-Stories

Beatrice Phillports, Mermaids

Richard Carrington, Mermaids and Mastodons

Gwen Benwell and Arthur Waugh, Sea Enchantress

The Lost Gods of England, Brian Branston

Wilfrid Bonser, A bibliography of folklore

Masaharu Anesaki, Japanese Mythology (also known as the History of Japanese Religion)

F. J. Child, The English and Scottish Popular Ballads

Moncure Daniel Conway, Demonology and Devil Lore

T. C. Croker, Fairy Legends and Traditions of the South of Ireland

N. Belfield Dennys, The Folklore of China [The book has the very unfortunate subtitles "and its affinities with that the Aryan and Semitic races", but it was written in the 19th century so...)

David Crockett Graham, Songs and Stories of the Ch'uan Miao

Thomas Keightley, The Fairy Mythology

P. Kennedy, Legendary Fictions of the Irish Celts

John Rhys, Celtic Folklore: Welsh and Manx

Sir George Webb Dasent's translation of Popular Tales from the Norse

The Norse Myths (as rewriten by Crossley)

Delaporte Press' Great Swedish Fairy Tales, illustrated by John Bauer

Inger and Edgar Parn d'Aulaire, D'Aulaire's Trolls (also known as D'Aulaire's Book of Trolls)

The Florence Ekstrand edition of Theodore Kittelsen's Norvegian Trolls and Other Tales

G. Fox, The Archaeology of the Cambridge Region

Edward L. Gardner, Fairies

M. Geoffrey Hodson, The Kingdom of the Gods

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, The Coming of the Fairies

Walter Burkert, Ancient Mystery Cults

Sabine Baring-Gould, Curious Myths of the Middle Age

#pierre dubois#bibliography#book list#resources#fairy tales#fairytales#book resources#mythology#folklore#folklores#fairies#fairy#fairy book#mermaids

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Notes from Ronald Hutton's lecture "Finding Lost Gods in Wales" from Gresham College

A major problem for locating Welsh paganism in historical terms is that there really is very little source material to work with, certainly not much medieval literature seems to have survived in Wales, at least when compared to other countries such as Ireland and Iceland. It was thought that several Welsh stories and poems reflected the presence of an ancient Druidic religion and thereby some form of paganism, but this idea has since been rejected. It is now believed these stories and poems originated much later, possibly dating to around 500 years after "the triumph of Christianity". Only four manuscripts written in the 13th and 14th centuries might contain some possible relevance to paganism. Hutton tells us that these are The Black Book of Carmarthen, The White Book of Rhydderch, The Red Book of Hergest, and The Book of Taleisin (so-called). About 11 stories from the White Book and Red Book were compiled into what was called The Mabinogion in the 1840s. None of these are stories are certain to be older than the 12th century, although the oldest stories in the Four Branches of the Mabinogion may have been written as far back as 1093, and according to Hutton some of the stories of the Mabinogion were actually inspired by foreign literature, including not only French troubadour stories but also Egyptian, Arabic, and Indian stories that were brought to Europe.

Hutton notes that, unlike in medieval Irish and Scandinavian literature, the stories of the Mabinogion don't seem to feature any gods or goddesses or their worshippers (at least not explicitly anyway), despite being set in pre-Christian times. Many characters have superhuman abilities, but it's apparently not clear if these are meant to be understood as gods, or magicians, or just narrative superhumans. If there are pagan survivals in these stories, it may be the presence of an otherworld realm called Annwn, often equated with the underworld, and/or the presence of shapeshifting abilities (and on this point I believe Kadmus Herschel makes a convincing point in True to the Earth about this being reflective of a non-essentialist pagan worldview). Of course, Hutton believes that these are generalized themes and no longer linked to paganism in themselves, but of course I'd say there's room for skepticism here (I'm not exactly picturing a Christian Annwn here).

An important figure within the Four Branches of the Mabinogion is Rhiannon, a woman from Annwn who often believed to be a surviving Welsh goddess or survival of the Gallo-Roman goddess Epona. Her marrying two successive human princes has been interpreted as signifying Rhiannon as a goddess of sovereignty. Hutton argues that this is not certain because Rhiannon does not confer kingdoms to her husbands, there is no clear sign of a sovereignty goddess outside of Ireland or British horse goddesses in Iron Age archaeology or Romano-British inscriptions. Hutton argues that it's more likely that Rhiannon was a member of human royalty or nobility rather than a goddess. Of course, this is perhaps a zone of contestation. Hutton does not deny the possibility that Rhiannon was a goddess, but believes that the decisive evidence is lacking. For what it's worth, Rhiannon is a unique figure in the literature of the time, as a being from the otherworld who chooses live in the human world and willing to stay there even after every misfortune or crisis she encounters, responding to every problem with an indomitable and perhaps "stoical" willpower and courage.

The mystical poems, or the court poets from 900-1300, are also thought to contain some aspect of lost Welsh paganism. These were to be understood as a kind of artistic elite that delighted in prose that was sophisticated to the point of being almost beyond comprehension. They apparently believed that bards were semi-divine figures, permeated by a concept of divine inspiration referred to as "awen". They drew on many sources, including Irish, Greek, Roman, and even Christian literature, but also apparently the earlier Welsh bards. Seven mystical poems are credited to Taliesin, and these could be dated any time between 900 and 1250, though contemporary scholars typically favour 1150-1250 as the likely timeframe. Despite probably being written at a time when Wales was likely already Christianized, the poems are repeatedly referred to as sources of paganism and ancient wisdom by modern commentators.

The poem Preiddeu Annwn is one "classic" example. It is the story of an expedition into the realm of Annwn, which is undertaken to bring back a magical cauldron. The poem that we have seems to be explicitly Christian, but it is often believed that this is merely a Christian adaptation of an older pre-Christian text. But apparently no one really knows the real meaning of the Preiddeu Annwn, not least because no one can agree on what a third of the actual words in the poem mean. No one really knows if Taliesin was demonstrating a certain knowledge that only he possessed or what, if anything, he was referencing, so in a way we just don't "get" his poem.

Over the years the court bards ostensibly developed a new cast of mythological characters, or simply an enhanced an older cast of characters, to the point that they seem superhuman or even divine, yet just as medieval as King Arthur or Robin Hood. One example of this is Ceridwen, a sorceress who first appears in the Hanes Taliesin. Court poets apparently interpreted her as the brewer of the cauldrons of inspiration, and eventually the muse of the bards and giver of power and the laws of poetry. In 1809 she was called the "Great Goddess of Britain" by a clergyman named Edward Davies, which has been taken up by many since. Then there's Gwyn ap Nudd, who appears in 11th and 12th century texts as a warrior under the command of King Arthur. In 14th century poetry he seems to have been interpreted as a spirit of darkness, enchantment, and deception, and in the 1880s professor John Rhys identified him as a Celtic deity. Another major character is Arianhrod, who first appears in the Fourth Branch of the Mabinogion as a powerful enchantress whose curses were unbreakable. Over time it was also believed that she could cast rainbows around the court, the constellation Corona Borealis was dubbed "the Court of Arianrhod", and somehow since the 20th century she was identified as an astral goddess.

Then we get to the canon known as "Arthurian legends": that is, the stories of King Arthur. Hutton says that these tales originated as stories of Welsh heroes who fought the English, and these stories also contained what are thought to be residual pagan motifs. One example is the gift of Excalibur from the Lady of the Lake, which is either based on memories of an older pre-Christian custom of throwing swords into lakes, the rediscovery of an older custom through finds, or even a persisting medieval custom of throwing a knight's weapons into a water. The Dolorous Blow which strikes the maimed king and turns his kingdom into a wasteland is thought to suggest a residual belief in the link between the health of a king and the health of a land, though the blow itself is inflicted by a Christian sacred object. The Holy Grail is often believed to derive from a pre-Christian sacred cauldron, but it was originally just a serving dish before becoming a Christian chalice.

And of course, there's Glastonbury, featuring as the Isle of Avalon, the refuge and possible burial site of Arthur. It has been thought since at least the 20th century that Glastonbury was a centre of paganism, but no remains have been found there which might suggest the presence of a pagan reigious site. And yet, in 2004, some prehistoric Neolithic post-holes were discovered near the Chalice Well garden in Glastonbury after the Chalice Well house started a kitchen extension. Although no deposits were found that suggest anything about the religious life of the area, the point stands that it was the first trace of anything Neolithic at Glastonbury. But there is perhaps always more to be found. As Hutton says, there are always new kitchen extensions, garden developments, street work, or any other renovation that might result in archaeological excavations, and we could find almost anything at any time. For my money, if there's hope anywhere, it's in that. Almost makes me want to get back into my childhood metal detecting hobby. It would certainly have a purpose: to rediscover anything from our pre-Christian past that could possibly be found.

From the Q&A we can incidentally note that many contemporary artefacts of Welsh national/cultural identity are very modern, they have nothing to do with some ancient past, but they weren't always to do with the romantic nationalism of Iolo Morganwg. The daffodil, for example, was probably first taken up as symbol of Wales in 1911, during the investiture of the then Prince of Wales. The leek, on the other hand, seems to have been symbolically associated with Wales since the Middle Ages, possibly as a reference to St David as his favorite dish, or possibly as a less then flattering reference to Welsh agriculture. The dragon, or rather Y Ddraig Goch (literally "the red dragon") as it is called here, dates back to a medieval narrative about a tyrannical king named Vortigern. He tries to build a castle but it repeatedly collapses, and according to the legend that's because two dragons, one red and the other white, are always fighting beneath the ground. The white dragon is supposed to represent the English and/or the Saxons, while the red dragon represents the Welsh and/or Celtic Britons. Although traditionally, at that time, Welsh princes took up the lion as their symbol much like English and other European royalty did, the Tudors established the red dragon as an official heraldic symbol of Wales to distinguish from English iconography, and that has been a mainstay of Welsh culture ever since. All-in-all, however, probably nothing to do with paganism here, unless the dragon has some older significance that we don't know about (and I'm inclined to be charitable here, considering that dragons in Christian symbolism usually represent Satan and/or evil).

There is the suggestion that Arianrhod is to be identified with Ariadne, the Cretan princess who became the lover and consort of the Greek god Dionysus. Both Ariadne and Arianrhod are associated with the Corona Borealis, which in Greek myth was a diadem given to Ariadne as a wedding present from Aphrodite. But that's about it. Any identification based solely on that would be a stretch.

There is the discussion of the legend of Bran, or Bran the Blessed, a king of Britain whose head was said to be buried in a part of London where the White Tower now stands. Hutton says it's possible that this may have reflected an ancient pre-Christian custom of burying parts of "special" people in "special" places to give them enduring magical/divine power, or alternatively that it references a Christian tradition of similarly venerating the relics of saints (itself possibly adapted from pre-Christian traditions in the Mediterranean, but that's another story; any input on that subject though would be much appreciated!). Hutton suggests that Bran's head being specifically buried beneath The White Tower is one of the best indications that the Four Branches of the Mabinogion as we know them were composed no earlier than the early 12th century, because the White Tower was built by William the Conqueror in 1080, and the Norman occupation in Wales as well as England at the time was part of the backdrop of the writing of the Four Branches. Hutton also suggests that stories concern parables from a distant, lost ancient time that were marshalled by Welsh poets who applied them as lessons for how to survive in the present, against the threat of Norman occupation. I should like to have answers on that front, because something about the reactivation of a distant past against the present order resonates very well with Claudio Kulesko's concept of Gothic Insurrection. It makes for interesting horizons, especially when applied to radical political dimensions relevant to things like the question of political identity in the context of the British union.

Relating to the legend of Wearyall Hill, the place in Glastonbury where Joseph of Arimathea supposedly planted the "holy thorn", there is the point made by the late historian Geoffrey Ashe (who, incidentally, died in Glastonbury) that none of the legends concerning Glastonbury have been or even can be disproved, which means that they all just might be correct. Hutton seems inclined to take what could be described as the "glass half full" side of that problematic, in that he thinks the great thing about myths and legends is that there also the possibility that there's something to them. I think that this presents possibilities for paganism, but in the sense that we are to look at it as an act of assemblage, or rather re-assemblage, and in a sense it works to the precise extent that we take it as medieval and contemporary mythology, without at the same time believing the lies that we tell ourselves through our romance and mythology.

Then there's the subject of the demonization of Gwyn ap Nudd in the Buchedd Collen, which incidentally counts as yet another Glastonbury legend. Hutton says that there is no doubt that Gwyn ap Nudd was demonized by Christians, but says that this was not specifically the work of the St. Collen myth. The legend of St. Collen was already fairly well-established in the Middle Ages, and the Welsh town of Llangollen takes its name from St. Collen. The legend goes that Collen was preaching in Glastonbury when Gwyn ap Nudd had taken over the Glastonbury Tor (Ynys Wydryn) and set up a mansion from which to tempt and seduce the inhabitants with vices and pleasures. Collen then goes to Gwyn ap Nudd's mansion and sprinkles holy water everywhere, causing it to explode and leave nothing but green mounds. Hutton suggests that by the 14th century Gwyn ap Nudd was already interpreted as a demon, but we don't really know how or why that happened. Here a horizon of assemblage emerges from the context of Christian demonization.

Gwyn ap Nudd, if taken as a Welsh or Brythonic deity, is interesting to consider as a demon invading Glastonbury and being exorcised by a Christian monk with holy water. There's an obvious question, albeit one that may have no answer: why does Gwyn appear as the subject of an exorcism myth in the context of a Christianized society? It seems plausible to consider Christians interpreted Gwyn ap Nudd as a demon by way of his already being the ruler of Annwn, an otherworld realm then recast as Hell. It may also be possible that Gwyn was a persistent reminder of an older pre-Christian polytheism, even if it's unlikely that he was actually worshipped by anyone living in the Middle Ages. Everything sort of hinges on the fact that the figure of Gwyn ap Nudd was pre-eminent enough in medieval culture, and enough of a thorn on the side of the Christian imaginary, to first of all be recast as an evil demon and then become the central antagonist of the legend of a Christian saint who exorcises him. That might allow Gwyn's presence in the legend to be interpreted as symbolic of the pre-Christian past, albeit through Christian eyes, and a figure who could represent its potential reactivation in Wales.

Lastly, there's the matter of apparent similarity between Welsh and Irish mythology, and the idea of a shared "Celtic origin" between them, in which we are again at a crossroads of possibility. That whole connection comes with a problem: there are definitely similarities between the Irish and Welsh characters at least in name, but these characters also to tend to share names more than they share almost anything else. The two explanations are either that these characters were deities that were worshipped in pre-Christian Wales as well as Ireland, or that Welsh authors were just well-acquainted with Irish folklore and literature and simply borrowed ideas from there. Hutton suggests that the first explanation may not be entirely wrong, or at least not completely invalidated, and leaves it up to the individual to decide between the two possibilities. It is very difficult to be certain is the first possibility holds up, and I have the suspicion it might not, at least not sufficiently. But it doesn't seem totally impossible, given the resonances between the mythical figures in Wales vs the pre-Christian gods of other lands. A relevant example would be Nudd, or Lludd Llaw Eraint, the mythical hero whose name was cognate with the Irish Nuada Airgetlam and apparently derived from the name of the ancient god Nodens. Not to mention Lleu Llaw Gyffes coming from the name of the Celtic god Lugus. That presents the slim possibility of connection, and perhaps assemblage by way of Irish myth.

If you want to see the full thing I'll link it below, here:

youtube

#wales#welsh paganism#britain#celtic polytheism#welsh literature#medieval literature#paganism#brythonic polytheism#glastonbury#arthurian legend#mabinogion#welsh mythology#british mythology#celtic mythology#gothic insurrection#Youtube

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

St. David’s Day Special: The Dragon Prophecy

~ ~

Welcome to Celtic Month! For the entire month of March, the Spring Vignettes series will be dedicated entirely to Celtic homage vignettes. Non-Celtic pieces will resume in April.

Quick clarification: It’s pronounced Keltic, unless it’s a sports team; and even then, any linguists in the room will cringe if you pronounce it Seltic.

Our first Celtic Month piece celebrates St. David’s Day, on March 1st, the national day of Wales. Have some cheese toast! Pet a dragon! Kiss a Welshman, if you can find one.

Before you read what the piece means to me, share what it means to _you_. I’m just the artist; you’re the beholder.

Leave a comment.

~ ~

The Welsh are the survivors of the Celtic Britons, who were the inhabitants of all southern Britain before the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes invaded and established what became England. “Welsh” is an Anglo-Saxon term; it means “other people” or “foreigners”, which is ironic, considering the Germanic-speaking peoples were the foreigners in the native lands of the Britons.

There is certainly no more famous Welshman than King Arthur Pendragon, a legendary king of yore who supposedly ruled Britain between the retreat of the Romans and the invasion of the Saxons. His legend, much-developed over the centuries, became well-known throughout Europe in later times.

A notable legend tells of the building of Dinas Emrys, a castle on a hill by the Glaslyn river. By some accounts, it was built by Uther Pendragon, father of King Arthur; by other accounts, it was Vortigern, the same foolish king of the Britons who later invited the Saxons into Britain as mercenaries to defend the Britons from the Picts.

After the king had chosen the hill on which the castle would stand, his builders went to work; but every day, they built up the walls, only for them to topple overnight. No progress could be made. At length, the king asked his wisemen to find the cause and the solution to the problem.

His wisemen told him that for the building to succeed, a sacrifice would be necessary; and the sacrifice must be a boy not sired by mortal man. Such a boy existed; a young boy named Merlin, or Ambrosius, the baptized son of a devil, who would go on to be known for his abilities in the magic arts.

(Foundation sacrifices were once an incredibly widespread custom; we know from archaeological evidence that the burying of a human victim under the foundation of an important building was practiced in ancient Ireland. Similar legends are told in Romania, Greece, Japan, and elsewhere. Animals were later buried under foundations after human sacrifices ceased.)

The boy was brought to the hill; and the king’s wisemen told the king to sacrifice him to appease the heathen gods so that the castle could be build. But the boy laughed at their advice, and told the king he knew much better. He told the king that if a hole were dug, there would be found a deep, dark pool; and in that pool, there would be found two dragons, one red, one white; and it was the fighting of these dragons that shook the hill each night and made the walls collapse.

The king had a deep hole dug; and indeed, there was found a deep, dark pool; and from that pool indeed emerged two dragons, one red, one white.

Freed from their imprisonment, the dragons fought viciously, until, despite being the lesser of the dragons, the red dragon defeated the white dragon, and drove it out of the land across the sea.

The boy then prophesied that, just as the red dragon triumphed over the white dragon, so the Britons would triumph over the invading Saxons.

And they did; until the death of King Arthur at the hands of his son Mordred, whereafter, the Saxons finally defeated the Britons, and drove them into the western mountains.

The great Welsh sagas, the Mabinogion, tell about how the two dragons originally became trapped under the site of Dinas Emrys, when an ancient Welsh king intoxicated them with a cauldron of ale and buried them to silence their deafening shrieking.

#st_davids_day#wales#welsh#dragons#uther#vortigern#merlin#dinas_emrys#arthurian#celts#celtic#spring#springholidays#digitalart#vector#mosaic#collage#inkscape

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

An archaeological study of skeletons from Greenwich pensioners and the conclusions about life at sea

In 1999-2001, an archaeological survey was carried out on the south-east corner of the Greenwich Royal Hospital Burial Ground. Greenwich pensioned Sailors and Marines were buried on this burial ground from 1749-1857. During this excavation 186 graves were uncovered, but only 107 of these were excavated, the others being reburied after a short survey.

Burial ground

The excavated area once held 20,000 inhabitants who were buried there over the course of time. However, 4000 were demonstrably removed and due to construction work and the two world wars, especially the second, great damage was left behind. What is striking, however, is that the marines and normal sailors are buried in simple, rather superficial graves in a NE-SW direction and not in a W-E direction as is usual in the Christian context. Also, many graves were double-occupied, or some were buried together with their partner, which explains the 5 women.

Double interment, skeletons 3211 and 3162

Officers were buried in a specially constructed mausoleum, the existence of which can only be proven by documents. No grave goods in the form of shoe buckles, buttons or even personal objects were found. It can therefore be assumed that they were all buried in simple shrouds.

The inhabitants

The skeletons revealed that they were mainly 105 adults and 2 sub adults. 5 skeletons were identified as definitely female and two as undefined because the skeletons were too damaged. Osteological examinations revealed an age range of 60-75, with the 71-75 group being the largest. The females were between 40-50 years old. Similarly, the average height of the men was 1.60-1.74m, with only a few being between 1.74-1.80m tall. The women were between 1.40-1.55m tall.

Compared to the other hospitals in Portsmouth, Haslar and Gosport where the injured and temporarily unfit Sailors and Marines were housed, the age range was as follows. The men there, and they were all men, were between 16-50 years old, with the majority being between 20 and 30 years old. There was no great difference in size to the pensioners in Greenwich. Therefore, it can be said that the Sailor and Marine standard height was between 1.60 and 1.75m.

Nationalities

The muster rolls of the ships showed that there were a variety of nationalities on board the ships, although the majority were British, Welsh, Scottish, Irish and Islanders. The remaining part consisted of continental Europeans, and there were Prussians, North Germans, Americans, Spaniards and even Frenchmen, but also Swiss and even Africans and Indians. Now, one might think that the residents of Greenwich Hospital would be exclusively British, Welsh, Irish, Scottish and Islanders, as it was a special honour to spend one's twilight years in this hospital. But the opposite was the case: as in the muster rolls, the residents were also of different origins and the examinations of the skeletons revealed three African men. So the selection was really based on performance and injuries and not on nationality.

Trauma - everyday injuries

Almost all of the skellets had serious injuries, but these had occurred a long time ago and could therefore be traced back to everyday life on board. Typical injuries in these cases were bone fractures, especially of the lower leg. But ribs and broken noses were also the most common. a few skeletons showed full-body fractures from a fall from a high height. On one ship, this was a typical injury from a fall from the rigging. Often these ended fatally for the person who fell, but also for one or the other who was standing on the deck at the same spot and was thus killed by the falling person. Few survived and often had permanent injuries that stayed with them for the rest of their lives.

Poorly reduced but well healed nasal fracture

The fact that the legs were often broken was often due to the fact that the people slipped during a storm, fell badly and broke their legs in the process. This also often led to broken ribs and noses. The latter were also caused by scuffles between the men themselves. Interestingly, hand and finger fractures were rare among the skeletons examined. Even though one might expect this to be the case when it came to handling in the rigging or guns. On the other hand, dislocations of the arms were found in many of the examined individuals, which can be attributed to the handling of sails. Joint diseases resulting from years of toil under the most difficult conditions, such as carrying heavy loads, repetitive jerky movements, could lead to these skeletal disorders, which usually occur in old age and are therefore not uncommon.

Trauma - Battle Injuries

In this case, the injuries are much more varied and leave the victims with permanent damage and limitations.

Amputation ans secondary osteomyelitis of the right femur

Skull injuries, soft tissue injuries in the form of splinter or bullet wounds, but also dislocations of extremities or even the loss of those extremities were often encountered. Musket wounds could lead to fractures, but also to more unusual injuries such as those suffered by retiree and ex-Marine Thomas Chapman. He died at the age of 72 in 1851, having suffered a gunshot wound to the face that left his lower jaw barely functional and caused severe problems with eating and speaking.

Below knee amputation of the right tibia and femur

Bone diseases

A very typical disease that many Sailors suffered from was osteoporosis and rheumatism. This was also clearly visible in these skeletons.

Infectious diseases

Tuberculosis and syphellis were the most common. The men could have contracted these diseases in the hospital, but it is most likely that they were contracted much earlier, as healing processes could be proven in various stages. Many also suffered from periostitis. Meningitis occurs after blunt injuries, bacterial infections or when osteomyelitis and bone inflammation spread to the periosteum. It severely restricts the mobility of the affected person and causes severe pain. Many also suffered from chronic sinusitis, an inflammation of the nasal sinuses, which was promoted by the constantly damp and windy weather. Since the men could not cure themselves properly and there were no antibiotics, this was a common illness, along with chronic bronchitis.

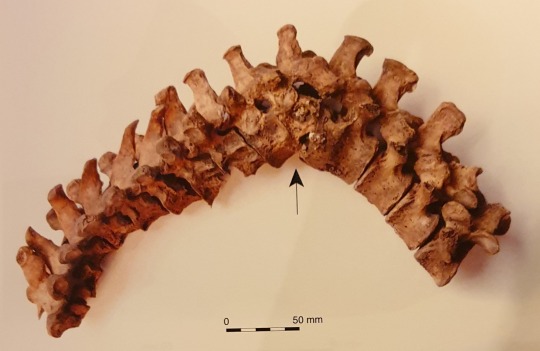

Pott's disease (tuberculosis of the spine). Note the crush fractures and the collapse of the vertebrae

Deficiency symptoms

Even when scurvy was treated, many suffered from it and it showed clearly in their bone structures, but vitamin D deficiency in childhood also led to rickets and could also cause bone softening and deformation in adulthood, which was extremely difficult for the person affected.

Surgeons interventions

There were not many Naval Surgeons, there were only 15 in 1797 and more than half of them were on half pay ashore. This, of course, led to a chronic lack of care on board the ships, which was often evident in the injuries and their healing processes. Even if there was a surgeon on board, this did not mean that the men were also well cared for, because many of the surgeons were poorly trained and had to learn their trade themselves. Many of the injuries were either badly splinted, which led to deformations in the bones, or even amputated. In this case, it only showed in the missing bones; the prostheses were not buried with them. Infectious diseases or chronic illnesses were only treated symtomatically, because either the knowledge or the means for treatment were lacking. Which is why the pensioners at Greenwich Hospital often had many illnesses and often suffered from them, but at least received some treatment. The men who were not admitted and no longer fit for service often died earlier and were very often under cared for.

Skeleton 3119 with post-mortem craniotomy

Post-mortem autopsies were even performed on four skeletons, whether for teaching purposes or for corrective reasons such as an active tuberculosis outbreak in the hospital cannot be precisely determined.

Summary

The skeletons examined, even if they were pensioners, showed the typical illnesses and injuries that a sailor could suffer at sea. Of course, the selection was quite small, but it showed well that the men, with the care they received and despite their limitations, managed to live to a fairly advanced age in a time of conflict. The abundant dataset reflects well what can often only be read in the logbooks. The origins of the men, the harsh life, the diet on board and the effects this could have on people in old age. In order to be able to provide a more accurate picture, further and more faithful studies are still needed.

#naval history#archeology#sailors and marines graves#greenwich pensioners#burial ground#18th 19th century#tw: skeleton#tw:bones

134 notes

·

View notes

Note

Why did you study sociology not history or something like that?!

The sociology program was actually additional study and not part of my initial college plans. But it was an amazing opportunity and we loved it! We got up close and personal with quite a few historic archaeological sites. Managed to visit some ley lines, too! But to answer your question, I’m currently working on my PhD in Welsh history with a concentration in archaeology.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mis Hanes LHDT+ 2023 : Gair y Dydd #1 -Lesbiaidd

LGBT+ History Month 2023: Word of the day #1 -Lesbian

(S'mae! This is the first in a series of Welsh LGBT terms which I will be posting over the first week in February for the UK's LGBT history month!. Follow to see more about my ongoing project to create Welsh's first LGBT dictionary)

Lesbiaidd

(adj. 'Lesbian')

Apart from some terms for gay men in Welsh, no one knows exactly when most modern LGBT vocabulary entered the Welsh language for the first time. This is true of Lesbiaidd (and Lesbiad and Lesbiaeth).

Last year I wrote a blog post for Hanes LHDT Cymru about the history of lesbian, bi, trans, intersex and asexual terminology in Welsh. You can find that here if you're interested!

Back to the post at hand- Geiriadur Prifysgol Cymru (GPC) only knows that Lesbiaidd emerged in Welsh in the 20th Century. But specifics of exactly when were elusive. That is until I began my research.

Currently, the earliest usage of lesbian terminology in Welsh I have on record is in Geiriadur Termau from 1973. The terms were probably in use somewhere before then, but this is the earliest dictionary to include Lesbiad and Lesbiaeth.

The next lesbian term to appear is in 1981, when the earliest instance of the plural of lesbian appears in Y Geiriadur Cymraeg Cyfoes as Lesbiaid.

In 1995 the orthography of Lesbiaidd appeared for the first time in Geiriadur yr Academy. Lesbiaidd has since become more common.

Inexplicably in 2008, Webster's Welsh-English thesaurus dictionary prints Clawdd (Dyke) as it's sole word for lesbian in Welsh!

We have here a sort of archaeological record of Welsh LGBT+ terms throughout the last Century. As far as current knowledge goes, lesbian terminology history in Welsh dates back to 1973 at least. That's 50 years ago this year!

I hope you enjoyed this first instalment of Welsh LGBT words of the day history! Share this or save if you liked it and be sure to follow for the rest in the series.

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

A 2,000-Year-old Iron Age Gold Treasure Found in Wales

Gold coins dating back more than 2,000 years have been found by metal detectorists in Wales, making them the first hoard of Iron Age gold coins to have been discovered in the country.

The 15 coins, which have been declared treasure, are known as staters. They were found the Welsh island of Anglesey, off the northwest coast of the country’s mainland.

Struck between 60 BC and 20 BC, the coins belonged to the Corieltavi tribe, who at the time inhabited the geographical area that is now England’s East Midlands, according to a National Museum Wales press release.

The precious metals were unearthed by three metal detectorists in a field between July 2021 and March 2022.

Lloyd Roberts, who said he has been a metal detectorist for more than 14 years, found the first coin.

“Finding a gold stater was always number one on my wish list,” he said in the release, adding: “That one coin alone would have made my year, but I went on to find another on my next signal.”

Roberts said that his friend, Peter Cockton, found the next three. They then contacted the Portable Antiquities Scheme, an organization which records such historical and archaeological finds.

Tim Watson, who said he only began metal detecting following encouragement from his father during lockdown, found the sixth.

“I rushed home to show my wife and we were both in awe of this coin, which was like nothing else I had found, immaculately preserved with such unusual stylised images,” Watson said in the release.

Watson said his enthusiasm led him to upgrade his metal detector and he found the remaining nine coins in the following weeks.

‘Rich archaeological landscape’

The gold coins’ elaborate design derives from those of Philip II, who ruled the ancient kingdom of Macedonia from 359 BC to 336 BC. The heads side of the coins shows the mythological deity Apollo’s wreath and hair, while the tails side shows a triangular-headed horse surrounded by symbols.

The coins were likely not used for everyday transactions, except potentially for some high-value purchases, according to the release. Instead, the staters are thought to have been used as gifts between the elites to secure alliances or show loyalty.

Another option is that the Corieltavi tribe used them to form part of an exchange for copper, which there were sources of in various parts of the island.

The staters could also have been used as “offerings to the gods” to fulfill a vow, according to National Museum Wales. Other archaeological finds from Anglesey, as well as Roman sources referring to the island that feature pagan priests, suggest the area was an important religious center at the time.

Gwynedd Archaeological Trust visited the site in September 2021 to see if there were any clues as to why the coins were buried there.

“This hoard is a fantastic example of the rich archaeological landscape that exists in North-West Wales,” said Sean Derby, Historic Environment Record archaeologist at Gwynedd Archaeological Trust. “While the immediate vicinity of the find did not yield any clues as to the find’s origin, the findspot lies in an area of known prehistoric and early Roman activity and helps increase our understanding of this region.”

Welsh museum Oriel Môn is looking to acquire the coins and put them on public display.

By Amarachi Orie.

#A 2000-Year-old Iron Age Gold Treasure Found in Wales#gold#gold coins#collectable coins#treasure#metal detecting#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#the Corieltavi tribe

162 notes

·

View notes

Note

ALSO HAVE YOU SEEN THIS?

I have indeed! Because Google is constantly spying on all of us, my news feed contains a lot of archaeological news, so I got several alerts when this first came out.

Peidiwch ag anghofio mai Cymro oedd y Brenin Arthur (don't forget that King Arthur was Welsh)

-Reid

103 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you have any niche interests that you haven’t really talked about online?

Oh this is a great question, I have to think about what counts as niche LOL, most of these probably aren't that niche but I'm not sure what else to call them

I definitely have a LOT of interests I don't post too much about, and some of which I haven't fulfilled IRL yet (like I don't have the means to pursue it as a hobby)

Not really "niche" I don't think and I do post about them (not super in depth though) in the sciences include but are not limited to:

Zoology (this is what I'm going to go to college for once I legally change my name)

Entomology

Linguistics

Archaeology

Paleontology

Biology in general

General environmental sciences

Geology

Astronomy

Anthropology

And probably others I am forgetting

Some hobby based interests of mine include the following (I'll put a note next to the ones I can't actually fulfill as of rn):

Tea drinking/brewing/etc. (probably the biggest one I have) (I fulfill this)

Bookbinding (I can't fulfill this yet)

Painting (not very niche) (I fulfill this but I do not feel comfortable sharing any paintings at the moment lol)

Puzzle-solving

Calligraphy/penmanship (not currently fulfilling this)

Reading (not niche at all but generally I don't post about any of the books I read)

Movies? Not inherently niche but I don't post about this and I'm into watching movies like old films, indie films, and cult classics

Macrophotography (not fulfilling this because I don't have the equipment but I do take pictures of bugs with the macrophotography feature on our old family video camera even if they're not great)

Writing and poetry (not niche but I don't post about this at all, I really want to write starting books and currently write poetry)

Theater/acting (not niche but I don't post about this) (also can't fulfill it)

Tarot/divination (I don't truly believe in it but it's just fun)

Okay I don't feel like reorganizing my list above but going from above here are more things I'm into that can't currently fulfill or just haven't fulfilled yet:

Ceramics

Crochet

Fishing (I've done this like three times)

Things like chess, mahjong, go, shogi, koi-koi and other hanafuda games (I don't know how to play chess which embarrasses me greatly)

Sewing in general

Quilting (I've made one quilt!)

Woodworking

Bug keeping (I want roly polies and snails and some others)

Vulture culture (not very legal...)

Foraging (I have an uncle very into this that I need to help me get into this)

Geocaching

Hiking

Biking (been getting into this a bit recently)

Some miscellaneous interests of mine that I'm not sure how to categorize include the following (some of these might be sciences but I feel like they're not as science-y as the ones I listed before)"

Mythology (this...counts as antropology but shh)

Conlangs (counts as linguistics? sort of?)

Vexillology

Language learning (semi-fluent in Spanish, currently learning: Irish, Welsh, (Scottish Gaelic), Scots, Lushootseed, Japanese, Chinese, I want to learn some other languages as well though)

Sunscreen/sunblock/UV protection (I have no idea what to call this but it's a big interest of mine)

Hedgehogs (big special interest of mine throughout my life)

I collect old books (none of them are all that old and I don't seek out any old titles, but if I see an old book I'll usually buy it, although I've had to put a hold on this because I don't have space) (oldest book I have is very late 1800s)

I have no idea how to phrase this but I love learning about the cultures of different countries as well as the differences in variations of English, I guess this is anthropology and linguistics

Lost media

History in general (this falls into archaeology and anthropology)

Dogs? I'm very into stuff about dogs, not like breeding or dog shows but just different stuff about the breeds or stuff about dogs

Animation (I'm into its history and animated features)

Dragons. As a child I was so autistic about them that I refused to read any book without dragons AND they had to be neutral to good dragons (ties into mythology)

Fairies/fae (ties into mythology)

Plushie collecting (I don't seek out specific plushes or try to fill certain spots in a collection, I just like collecting whatever I like)

There's probably more I'm forgetting

#asks#yoshifawful64#you can answer the question for yourself also#i would love to hear#i just. cant send asks bc im suspended#you can reply or DM me LOL

6 notes

·

View notes

Note

Can you tell us more about who England refers too as mother? And did you divide the UK siblings roughly into two pairs because of Roman Britain? I'm sorry you just keep dropping hints and no one else has asked 💌

Oh lord, okay. So disclaimer, working with prehistory is a fucking crap shoot. Archaeology has a lot of interpretations and not as many facts as historians and archivists like me, especially who studied modern history, would like. And even when history does come to the islands in the form of the Roman writers, that is also largely questionable because propaganda is as old as human communication. So I try to work with what we do know, but before a certain point, I'm basically writing fantasy. But also, no one has to work with history ever in a fucking stupid anime fandom. I'm just a diagnosed anxious headcase who copes with the uncertainty of existence by researching the fuck out of every choice I've ever made sober, including this shitshow of a blog and predecessors. Most of my focus is on much later history, so I'm taking a minimalist approach here and making as little work for myself as possible while at least taking some guidance from history to fit the themes I like so none of this is likely going to be the best take, tbh. That said, onwards into the breach, I fucken guess.

Can you tell us more about who England refers to as mother?

Yes. So most of the time, the conglomerate characters of "Germania" or the fanon "Native America," where dozens and hundreds and thousands of politically interlocked or entirely separate cultures are smushed into one character, make zero sense to me. In the case of Native America, it's downright racist, and in the case of Germania it's basically sucking Tacitus off 2,000 years after the fact. But Brittania could make sense. Being an island separated from mainland Europe made for some attractive socio-political and cultural unity hinted at in writing after the Roman invasion and before the fact in the archaeological record. But how long before the Romans? Where do I begin with Brittania, eh? The Red Lady of Paviland? The Creswell Crags? The Starr Mesolithic Site? Neolithic Chambered Tomb-Shrines? Stonehenge? The Iron Age Hillforts? Ah! There we go, the Celtic arrival in Britain. i.e. the option that makes me do the least work to get the job done. The Celts arrive in Britain about 1,300-800 BCE and in Ireland about 800-500 BCE depending on who you read. There is one tribe among the Celtic that had strong links to Britain and Ireland. The Brigantes were stuck in the border region between what is today Scotland and England, with at least some sort of material connections in Wales and Ireland. So my shortcut to a decent storyline that had some basis in fact, was to have her people interpret her as their patron goddess of Brigantia and link her tightly to Celtic paganism and weakened by the invasions of Rome but also the widespread adoption of Christianity in the 5th century. She was a proud woman who enjoyed the worship she once knew and who loved her children fiercely. She was every bit a Cartimandua or Boudicca. And when Christ and his nails bled her to death, her sons eventually dug her a barrow at the foot of an iron age hillfort, and her only daughter braided her hair and placed her golden jewelry on her one last time and their world was never the same.

And did you divide the UK siblings roughly into two pairs because of Roman Britain?

Yes and no. The Romans did take and hold England and Wales but Wales was much harder to hold onto. Under the Romans, life didn't change there or in Scotland nearly as much as in England. My main reason for splitting them into Brighid and Alasdair and Rhys and Arthur beyond much more modern politics is linguistic. Scottish Gaelic is much more related to Irish than it is to Welsh. And the Welsh word Cymru once referred to both the Welsh and Cumbrians. Now Cumbrian is a fascinating little language that is now dead, but it left a fantastic legacy in its counting system. @oumaheroes headcanons it as being something he uses to refer to his weans, and I, sobbing, concur wholeheartedly. I also have made random references to a shitfaced Arthur babbling in Cumbrian. So with that being a Celtic language in what is today England, et voila, two pairs.

#Britannia and her children || they made a desert and called it peace#the ask box || probis pateo#Alasdair || my heart's in the highlands#Arthur || stone set in the silver sea#Brighid || an bearna bhaoil#Rhys || my word for heaven was not yours

66 notes

·

View notes