#western society

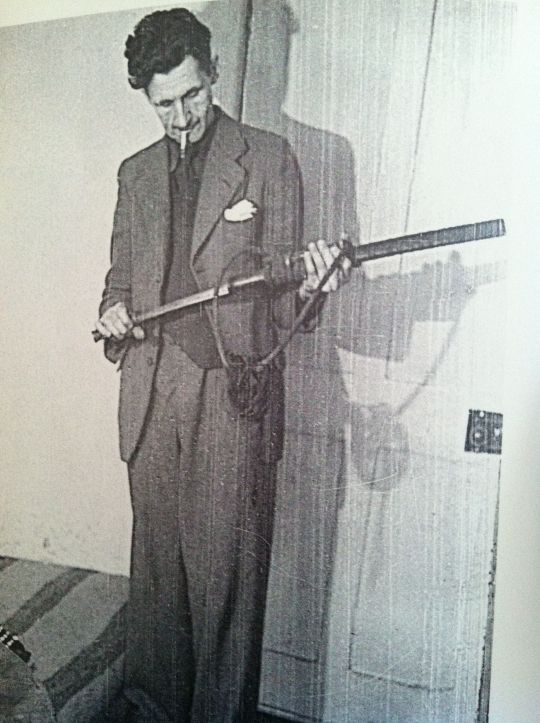

Photo

For 200 years we had sawed and sawed and sawed at the branch we were sitting on. And in the end, much more suddenly than anyone had foreseen, our efforts were rewarded, and down we came. But unfortunately there had been a little mistake…The thing at the bottom was not a bed of roses after all; it was a cesspool full of barbed wire. ... It appears that amputation of the soul isn't just a simple surgical job, like having your appendix out. The wound has a tendency to go septic.

- George Orwell, Notes on the Way

Orwell on post-Christian societies.

#orwell#george orwell#quote#society#post-christian#post-christian society#ideology#leftism#enlightenment#conservatism#progressivism#politics#history#western society#western europe#soul#collapse

239 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gotta love when an effortpost about a historical person immediately destroys any credibility with the most insane assertion of the week. "This guy was the first artist in the entire history of Western art to drew the naked female form without shaming her or making it religious" thanks for saying this right away so i don't waste time reading the rest of your post

#Western society#where's the map showing how often each country is included in the vague blob we call

204 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’ve come to notice something about most internet discussions regarding societal norms and cultural differences

when someone mentions “the east”, they’re probably exclusively referring to Asia, but not Russia, Central Asia, the Middle East, or certain parts of South Asia

when someone mentions “the west”, they’re exclusively referring to the white populations of the USA, UK, Australia, and sometimes Canada

you’ll rarely find someone actually including Eastern Europeans or any minorities not mentioned above to be included unless they themselves are part of that group

its kinda weird

#internet#discourse#western society#eastern society#middle east#asian#africa#north america#australia#oceania#south america#latin america#europe#eastern europe#usa

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

The naming convention used in Eritrea and Ethiopia does not have family namesand typically consists of an individual personal name and a separate patronymic. This is similar to Arabic,Icelandic, and Somali naming conventions. Traditionally for Ethiopians and Eritreans the lineage is traced paternally; legislation has been passed in Eritrea that allows for this to be done on the maternal side as well.

In this convention, children are given a name at birth, by which name they will be known. To differentiate from others in the same generation with the same name, their father's first name and sometimes grandfather's first name is added. This may continuead infinitum. Outside Ethiopia, this is often mistaken for asurname or middle name but unlike European names, different generations do not have the same second or third names.

In marriage, unlike in some Western societies, women do not change their maiden name, as the second name is not a surname.

#african#africans#western societies#western society#ethiopia#eruopean names#eritreans#ethiopian names#eritrean names#afrakan#kemetic dreams#afrakans#brown skin#african culture#afrakan spirituality

104 notes

·

View notes

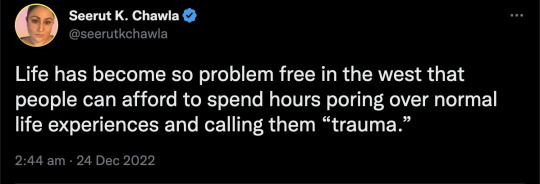

Photo

#Seerut Chawla#western society#first world problems#trauma#fredsskadade#religion is a mental illness

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

An obsession with Greek mythology directly ties into Catholic guilt

This is because Catholicism overtook Roman mythology, which was derived from Greek mythology, and became the normal religion in Rome. Society today still clings to the Roman's model, which in turn, means that Christianity as a whole is a large religion. So, any individual interested with Greek mythology that is around a Roman based society (typically western), would face some form of Catholic guilt.

In this essay I will-

#in this essay i will#catholic guilt#greek mythology#roman mythology#catholiscism#western society#I've been listening to songs based on greek mythology and it shows.#i might actually do this#i should go to bed

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Passport Bros vs Western Women

Passport bros, in majority of western women's eyes, are:

Ugly losers who have no game and can't get women in their own country. They are slimy and disgusting pedos, mediocre at best, dusty and broke tricks (don't forget sex tourists) taking advantage of "poor" and "uneducated" women that speak little to no English that want you only for your money and green card to get away from their "miserable lives". All the Passport Bros want is to use women in said countries for sex and nothing more. (Note: some men out there think like the women do about the passport bros too.)

These women who criticize the men, in their words, really don't care about these men who leave the country for another woman... even though they constantly make videos and have interviews about them. They are the same ones who've created the Passport Sisters movement in response to the Passport Bros. They are also the same ones who go to Jamaica to rent dreads and get their pum pum rubbed and their back blown out on a raft by men with STDs and request plastic bags to use as a condom 😑

One side is successful finding their peace and happiness in another country with their girlfriends / wives, while the other side is showcasing fatherless behavior while vacationing in different countries.

Each day, these women are giving men more reasons to drop everything in the west and leave for something better, and I can't blame men for wanting something better.

These strong and independent ladies that criticize passport bros consider themselves to be the best of the best because they make more money than men and got a bunch of materialistic things to go along with their lifestyle, yet they fail every time at keeping a man. Lack of essential skills, ridiculously high standards for what they want in a man (especially towards a black man), nasty attitudes and more are the reason why men don't want anything to do with the western women. This is why questions like "what do you bring to the table?" is asked towards women, because it seems like the majority bring nothing but problems... always...

By the way, this passport bros phenomenon is not new. White men have been doing it for a longer period of time than black men, and now that the good black men of America (and more) are speaking out and making moves, women want to throw a fit?

To the women: You talk shit about other countries and the women from said countries that you have no knowledge of, all the while putting down the men that you don't even want nor care about in the first place. Make that make sense. It's fine when you women go out and travel to different countries and have your little escapades, but when men do it, it's a problem? I thought you didn't care. Keep that energy all the way through.

Some of us good men are tired of being treated like shit. We will not be your last resort when all else fails. Lay with the dogs that treat you like what you are: shit. We do not want you.

Fellas, go where you are treated best. Travel around, experience new things, upgrade your life. You deserve better.

#dating#passport bros#travel#women#western society#western women#asia#latin america#rent a dread#go where you are appreciated

7 notes

·

View notes

Link

by Alistair Begg | Writing on the state of Western civilization a little more than a decade ago, English journalist Melanie Phillips observed, “Society seems to be in the grip of a mass derangement.” There’s a “sense that the world has slipped off the axis of reason,” causing many to wonder, “How is anyone to work out who is right in...

#nature of sin#TGC#The Gospel Coalition#Alistair Begg#One Hope for Our Mass Derangement#insanity#western society#thegospelcoalition.org

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Me: I never understood why Edmund was always on about Turkish delight

Friend: Yeah, I like my delights like I like my public education : western and untempting.

2 notes

·

View notes

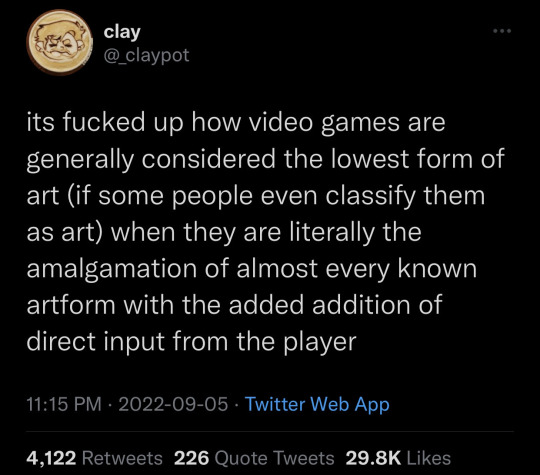

Photo

Quicumque amisit dignitatem pristinam, ignavis etiam iocus est in casu gravi.

- Phaedrus

Whoever has lost his ancient dignity Is a joke to baser men in the midst of grave mistake.

#phaedrus#latin#classical#quote#dignity#tradition#custom#identity#femme#statue#beauty#heritage#western society#values#culture#civilisation

195 notes

·

View notes

Text

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

There were studies showing that future homosexuals had different personalities in childhood; studies showing that homosexual men had differences in brain anatomy from heterosexual men; several twin studies showing that homosexuality was highly heritable in Western society; and anecdotal reports from homosexual men to the effect that they had felt 'different' from an early age.

"Nature via Nurture: Genes, Experience, and What Makes Us Human" - Matt Ridley

#book quote#nature via nurture#matt ridley#nonfiction#gay#homosexual#lesbian#twin study#brain#anatomy#brain anatomy#heritability#the west#western society

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Younger Memnon is probably one of the most impactful sculptures in history, yet very few know its name.🏛

𓀲

#history#younger memnon#art#ancient egypt#thebes#sculpture#work of art#british museum#ancient history#ramesseum#ancient art#new kingdom#art history#statue#egyptian art#ramesses ii#english history#memnonianum#western society#pharoah#museum#ancient#ancient egyptian history#london#united kingdom#masterpiece#nickys facts

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

By: Rob Henderson

Published: Mar 17, 2024

Back when I was deployed in 2011, I read a fascinating passage in How the Mind Works by Harvard psychologist Steven Pinker.

Pinker, describing the power of familial bonds, wrote, “every political and religious movement in history has sought to undermine the family. The reasons are obvious. Not only is the family a rival coalition competing for a person’s loyalties, but it is a rival with an unfair advantage: relatives innately care for one another more than comrades do.”

Joseph Henrich, professor of evolutionary biology at Harvard, explores the consequences of this idea at length in his recent book The WEIRDest People in the World: How the West Became Psychologically Peculiar and Particularly Prosperous. The book contains a dazzling array of evidence to support Henrich’s thesis for why variation exists among societies, and, in particular, why Europe has played such an outsized role in human history. The word “WEIRD,” stands for “Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, Democratic.” It is also a convenient way to communicate that people from such societies are psychology different from most of the rest of the world and from most humans throughout history.

In short, the Western Church (Henrich’s term for the branch of Christianity that rose to power in medieval Europe) enacted a peculiar set of taboos, prohibitions, and prescriptions regarding marriage and family. This dissolved Europe’s kin-based institutions, and gave rise to a more individualistic psychology, which in turn spurred the creation of impersonal markets in which people grew used to interacting with and trusting unrelated strangers, and propelled the development of voluntary institutions, universally applicable laws, and innovation.

Characteristics of WEIRD people

WEIRD people are hyper-individualistic, self-obsessed, nonconformist, analytical, and value consistency. We try to be “ourselves” across social contexts and prize “authenticity.”

The book reviews research indicating that Americans rate those who show behavioral consistency during interactions in different contexts as more “socially skilled” and “likable” compared to those who are more behaviorally flexible. In contrast, non-WEIRD people view personal adjustments as reflecting social awareness and maturity.

In addition to valuing behavioral consistency, WEIRD people are more likely to feel guilt than shame. In contrast, non-WEIRD people are more likely to experience shame as opposed to guilt. Shame is the result of not living up to the expectations of one’s community. Guilt is a private emotion that results from falling short of our own expectations, rather than the community’s.

Relatedly, a recent study found that people can experience shame for being accused of actions they didn’t commit. The accusation alone was enough to elicit this powerful emotion. Shame is a reaction to others believing we did something bad rather than a reaction to actually doing something bad.

Delayed gratification also appears to be more prevalent in WEIRD societies. When researchers offered WEIRD people the choice between a smaller monetary payment up front, or a larger sum later, they tended to choose the larger sum. In contrast, most non-WEIRD people preferred the immediate, smaller, reward.

Interestingly Henrich relays data suggesting that greater patience is most strongly linked to positive economic outcomes in lower-income countries. Put differently, the tendency to defer gratification seems to be especially more important for economic prosperity in countries where formal institutions are less effective. This pattern holds within countries as well, such that patient people obtain higher incomes and more education. Patience is related to success after controlling for IQ and family income, and, even within the same families, more patient siblings obtain more education and higher earnings later in life.

Moreover, WEIRD people are more likely to adhere to rules even in the absence of external sanctions. The book reports that until 2002, U.N. diplomats from other countries were immune from having to pay parking tickets in New York City. Diplomats from the UK, Sweden, Canada, and other countries received a total of zero parking tickets. But diplomats from Bulgaria, Egypt, and Chad, among other non-WEIRD countries accumulated more than 100 tickets per member of their respective delegations. When diplomatic immunity was lifted, parking violations declined, but the gap between countries persisted.

But while they may be patient and rule-following, WEIRD people are more likely to be fair-weather friends. Relative to other populations, WEIRD people assign higher value to impartiality and show less favoritism toward friends, family members, and co-ethnics. We are more likely to abhor nepotism and believe in universally applicable principles.

Suppose you are in a car being driven by your close friend. While driving over the speed limit, he hits a pedestrian. His lawyer tells you that if you testify under oath that he was not speeding, it may save him from serious legal consequences. Does your friend have a right to expect you to lie for him, or do you think he has no right to expect this?

This is called the Passenger’s Dilemma, which has been posed to citizens from countries around the world. People from Canada, Switzerland, and the U.S. generally say your friend has no right to expect you to lie. But most non-WEIRD citizens from places like South Korea, Nepal, and Venezuela say they would willingly lie to help their friend.

WEIRD people make bad friends, but they are more willing to trust strangers. Henrich reports responses from across the globe to the question, “Generally speaking, would you say that most people can be trusted, or that you need to be very careful in dealing with people?” In WEIRD countries, levels of trust were consistently above 50%. In contrast, in Brazil, Trinidad, and Tobago, levels of trust were below 10%.

Furthermore, there is an obsession with intentions—the invisible contents of a person’s mind. When determining the severity of a moral violation, what matters more: Intentions or outcomes? This question varies a lot across societies. WEIRD people are extreme outliers, placing a lot of importance on whether someone “meant” to do something, where as non-WEIRD people focus more on what actually happened and who was affected.

Across 10 diverse societies, Americans placed the most value on intentions, while individuals from Fiji, Papua New Guinea, and Namibia focused more on outcomes. The question of intent is relevant to our current sociopolitical climate. Consider the recent firing of New York Times reporter Donald G. McNeil Jr. The Times concluded that while McNeil showed poor judgment when he repeated the N-word used by another individual, they also stated that he did not harbor “hateful or malicious” intent. Still, Times Executive Editor and Managing Editor fired McNeil anyway, saying “We do not tolerate racist language regardless of intent.” A UCLA professor was suspended under similar circumstances. At least within the context of language, the U.S. may be shifting away from WEIRD moral psychology.

Overall, countries with greater patience, behavioral consistency across social interactions, trust of strangers, adherence to impartial norms, and concern with intentions, have higher GDP, more economic productivity, less corruption, and greater rates of innovation.

Of course, one might argue that such differences stem from formal institutions like courts, police, and governments. But, Henrich asks, how does one get there in the first place?

Why Are We WEIRD?

One key factor is religion. Specifically, what Henrich and other researchers refer to as “Big Gods”—deities that oversee what people do, care whether they behave immorally, and punish wrongdoers. Societies that believe in moralizing gods, who punish wrongdoers, tend to have WEIRDer psychologies. Henrich writes, “if you are weird, you may think that religion always involves morally concerned gods who exhort people to behave properly.” But in fact, this aspect of religion is atypical. For instance, Roman gods were not concerned about immoral behavior such as lying, cheating, and stealing—what upset them was the violation of oaths taken under their name. For instance, merchants had to swear sacred oaths to affirm the quality of their goods. For Roman gods, it was their honor they were concerned about, not the acts themselves.

Across countries, belief in a contingent afterlife that is dependent on how one behaves now is associated with greater economic productivity and less crime. The book communicates research based on data from 1965 to 1995 and found that if the percentage of people in a country who believe in hell and heaven increases by 20 percent, that country’s economy will grow an extra 10 percent over the next decade. Additionally, the greater the percentage of people in a country believe in hell, the lower the murder rate. Intriguingly, the opposite is true for belief only in heaven: That is, the more people within a country believe in heaven but not in hell, the higher the murder rate.

Henrich posits that Christianity, or what he terms the “Western Church,” began in about 400 CE to spread throughout Europe and slowly eroded intensive kin-based institutions and weakened ties with extended family members within communities. The Church supplanted ancestral gods such as Thor and Odin, old Roman deities like Jupiter and Mercury, as well as other variants of Christianity. Additionally, the Church initiated what Henrich terms the “Marriage and Family Program” (MFP). This program dissolved people’s connections to their extended family, banned cousin marriage, and gradually, made the nuclear family and voluntary associations the center of social life.

The extreme incest taboos were enacted in part because the Church did not want to compete with family members for people’s loyalty. Weakening family ties bolstered the Church’s place in people’s hearts. Additionally, the message of the Church spread when young adults would leave their homes in search of a spouse, and when they would form voluntary associations. The Church also blocked the transferring of inheritance to anyone save the genealogical line of descent—that is, birth children, which furthermore eroded kin-based relations.

In more traditional communities of extended families, cousin marriage is rife. But in the medieval European world of scattered farms, villages, and small towns, the extreme incest taboos of the Church compelled people to travel far and wide in search of spouses, who were often in different tribal or ethnic groups. The longer a country’s population was exposed to the Church, the weaker its kin-based institutions and the lower its rates of cousin marriage. Henrich writes, “Each century of Western Church exposure cuts the rate of cousin marriage by nearly 60 percent.”

This had consequences for the personalities of WEIRD people. Success in kin-based institutions relies on conformity, deference to traditional authority, sensitivity to shame, and an orientation toward the collective. In contrast, when relational bonds are weaker and people have to find ways to get along with strangers, success arises from independence, less deference to authority, more guilt, and more concern with cultivating personal attributes and achievement. The emphasis on the individual, as opposed to the group or clan, is characteristic of weird societies.

Henrich shows that the percentage of cousin marriages across countries predicts levels of individualism. The U.S. is famously individualistic, and indeed it scores the highest on the individualism scale and among the lowest on prevalence of cousin marriage. In contrast, countries with a higher prevalence of cousin marriage such as Malaysia and Indonesia score lower on individualism. Prevalence of cousin marriage is also associated with lower rates of trust for strangers, higher willingness to lie for a friend, and lower rates of blood donations.

When researchers invited university students in various countries to play economic games in which they could easily cheat to win more money, students from countries with more cousin marriage were more likely to do so relative to students from countries with fewer intrafamilial marriages. Such differences exist within European countries as well. For example, southern Italians have higher rates of cousin marriage, along with lower trust of strangers and lower blood donations compared with northern Italians.

The Church’s Marriage and Family Program insisted on monogamous marriage, which constrained the darker aspects of male psychology. Polygynous societies create large numbers of young, unmarried men with few prospects and no stake in the future. Henrich argues that the MFP’s strong monogamous marriage norms constrained the darker aspects of male psychology and gave weird societies an edge. Polygynous societies have what Henrich refers to as a “math problem.” Imagine a society with 100 men and 100 women. If 1 man takes 10 wives, that leaves 90 single women and 99 single men. If each of the women pair up with one man, there will be 9 single men leftover. These 9 single men are likely to create problems. Henrich documents how across multiple continents in distinct historical epochs, rulers and kings and emperors often took thousands of wives and concubines, leaving lower ranking men without partners. Such men, especially when young, can be a threat to societal stability.

The book cites a famous study revealing that getting married reduces a man’s odds of committing a crime. The researchers also found that when men got divorced or their wives passed away, their likelihood of committing a crime increased. In short, monogamous marriage cultivated stability in WEIRD societies.

Higher rates of impersonal trust, individualism, and voluntary association helped give rise to markets because people were more willing to trade and deal with strangers. Markets themselves, Henrich argues, promote those same WEIRD traits in a kind of feedback loop. Henrich reports that among hunter-gatherers and subsistence farmers around the world, people who lived closer to markets in which they could buy and sell goods such as honey, butter, and candles played more fairly when researchers invited them to play economic games against strangers to win money. “This research,” the book states, “strongly suggests that greater market integration does indeed foster greater impersonal prosociality.”

Researchers visited 3 different BaYaka communities, a population in the Congo Basin. Two communities were traditional nomadic foragers living in a remote area. The third community lived within a town itself that contained a market. The researchers offered the people a choice between receiving either one soup stock cube now or 5 cubes tomorrow. 54 percent of the BaYaka living within the town chose to wait for the 5 cubes compared with only 18 percent of those living in nomadic camps. The reason is that while people in kin-based communities care a lot about being fair and honest with fellow group members, they have less concern for strangers. Conversely, people used to interacting with strangers in a market context have an incentive to develop good relationships with them.

Still, there may be downsides to impersonal markets. One is that in commercialized societies in which the social sphere is governed by market norms rather than dense networks of interpersonal relationships and extended family can lead some to feel alienated and exploited. The Harvard philosophy professor Michael Sandel, among others, has written about how market relations can crowd out more personal and satisfying interactions.

Markets also shaped WEIRD psychology as it relates to time. The book points out how people in more traditional small-scale societies have a more relaxed relationship to time, and feel less inclined to be punctual. In contrast, WEIRD people generally prefer to be prompt. For Westerners, time is analogous to money. As the book puts it, “WEIRD people are always 'saving' time, 'wasting' time, and 'losing' time...many of us try to 'buy' time...obsessed with thinking about time and money in the same way...Ben Franklin coined the maxim ‘Time is money,’ which has now spread globally.” Henrich shows data indicating that people in more individualistic cities like London and New York walk much faster on average than people in less individualistic cities like Malaysia and Jakarta.

The commodification of time and amplified individualism gave rise to WEIRD societies prizing personal success and investing in one’s own attributes and skills—accruing individual achievements. This shift, alongside the swelling stream of commercial goods in a market society, heightened materialism. Henrich contends that people wanted to buy more items because such items indicated something about their owners and what they valued. “From Bibles to pocket watches,” the book notes, “people wanted to tell strangers and neighbors about themselves through their purchases.”

Relatedly, the book reports research that calls into question some longstanding theories within psychology and behavioral economics, such as the endowment effect. The idea is that people supposedly place greater value on items they possess. For example, if you randomly give one of two different types of pens to WEIRD participants and offer them the chance to exchange it for the other one, they tend to keep the one they were given. Personally owning a thing somehow makes it more valuable.

But the book reviews research at odds with this idea. Researchers randomly gave members of the Hadza—a group of modern hunter-foragers—1 of 2 differently colored lighters to make fire and asked them if they wanted to exchange it for the other color. They traded their lighters about half the time. In other words, they don’t seem to fall prey to the endowment effect.

However, when the researchers administered the study to another Hadza community that was more market-integrated and had experience selling arrows, bows, and headbands to tourists, they kept their lighters 74 percent of the time—indicating that they had fallen prey to the endowment effect. Henrich goes on to cite research showing that Americans exhibit a stronger endowment effect than East Asians. Henrich posits that impersonal markets cultivate an emphasis on personal attributes, and WEIRDer people tend to view objects as extensions of themselves. Thus, they are reluctant to part with them. Another reason is that in kin-based communities, people simply can’t become too attached to their possessions, because social norms dictate that they must be shared.

For example, Henrich contends that the individualism and market societies that arose in part from the policies of the Western Church had profound effects on WEIRD personalities. Psychologists have long assumed that the “Big Five” personality profile, comprising openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism was universal, and that every person could be mapped along these personality configurations. But Henrich refers to this concept as the “WEIRD-5,” because researchers have failed to identify the 5 dimensions in non-student adult populations in Bolivia, Ghana, Kenya, Laos, Sri Lanka, Vietnam, and Macedonia, among other non-WEIRD locations. The reason is because WEIRD societies prize individualism and the cultivation of personal attributes. In contrast, in kin-based groups that are centered on the community rather than the individual, people experience less need to fully express and cultivate their underlying traits. Describing the Tsimane, a population of farmer-foragers, Henrich writes, “everyone has to be a generalist. All men…have to learn to craft dugout canoes, track game, and make wooden bows. Extroverts can’t become insurance salesemen…introverts can’t become economists.”

This WEIRD psychology had implications for laws. Freed from kin bonds, Europeans in medieval Europe were more mobile and flocked to urban centers in search of economic opportunities and romantic mates. Laws became centered more on individuals as opposed to social position or family lineage. Individual-centered legal developments gave rise to “rights,” which Henrich observes, is a historically unusual concept. As he puts it, “from the perspective of most human communities, the notion that each person has inherent rights…disconnected from their social relationships or heritage is not self-evident…from a scientific perspective, no ‘rights’ have yet been detected hiding in our DNA or elsewhere.” Furthermore, the book posits that in many societies, the purpose of law is not to defend individual rights or preserve an abstract sense of justice. Rather, laws are to maintain peace and restore social harmony. Universally applicable laws independent of family, lineage, or relational ties, arose from the individualistic psychology of WEIRD societies.

Toward the end of the book, Henrich also suggests that the impersonal forces of WEIRD societies spurred technological innovation, because individuals were more willing to share their ideas with unrelated people, and were eager to broadcast their ideas because of the associated prestige.

Interestingly, the book suggests that the nuclear family also encouraged innovation. Typically, in kin-based clans, young men typically had to wait their turn to take charge, as the elder men were held in higher esteem. But in medieval Europe, young men were the head of their small households and were perhaps less apprehensive about breaking tradition and more willing to take risks.

A professor once told me a story. He said that as a young man he was at a synagogue, engaging in prayer. He thought prayer was silly, but went along with it to please his family. The rabbi asked them to pray for their loved ones. My professor then said that this reminded of a family friend who had been sick, and, later that week, went to bring him soup. He then asked me: does praying for our loved ones work?

As the world’s leading authority on cultural evolution, a key point Henrich hammers home is that people in both WEIRD and non-WEIRD societies have no idea how and why their institutions and norms actually work. As he puts it, “people rarely understand how or why their institutions work or even that they ‘do’ anything. People’s explicit theories about their own institutions are generally post hoc and often wrong,”

For example, the book describes research from the anthropologist Donald Tuzin, who reports how an Arapesh community called Ilahita had integrated 39 clans encompassing more than 2,500 people. The cooperation of this large community was sustained through mutual obligations, reciprocal responsibilities, and social rituals infused with supernatural beliefs. The villagers believed their community’s prosperity was the result of their rituals. They believed such rituals pleased their gods. And when cooperation broke down, elders attributed this to members not adhering to the rituals properly. The elders would then call for additional rites to better please their deities. This was effective in repairing social harmony.

Henrich describes how it was in fact the social bonding resulting from the activity, rather than pleasing their gods, that resulted in improved cohesion. It is likewise probable that Westerners are mistaken in how and why their own norms and institutions operate, and may well be mistaken in undermining them.

#Joseph Henrich#Rob Henderson#The WEIRDest People in the World#WEIRD#Western Educated Industrialized Rich Democratic#western civilization#western society#prosperity#individualism#individuality#psychology#human psychology#religion#religion is a mental illness

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Greeks were honestly so pretentious and wrong about so much how did they have so much effect of western society

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some women have become so desensitized to men that ain't shit, that they can't tell the difference between a good man and a bad apple when they complain about where have all the good men gone.

Then you have the ones that can tell the difference but choose to be with the ones that have that "edge" to him -- ignoring all the red flags he has because he looks good, puts it down in bed and more regardless of his financial status.

The hardworking, responsible, good men are rejected until the women who are all used up want to settle down and run back to the men they've rejected in the past. It doesn't matter what your standards are as a man, but you have to be 6'2"+, make six figures, have six pack abs, be a successful entrepreneur, look like Lebron James, have an 8 inch dick, don't like dogs, don't like cats, etc. etc. etc. If you don't check all of their boxes, they don't want you.

Modern dating in a nutshell.

9 notes

·

View notes