#why are my low effort star wars memes the most popular

Text

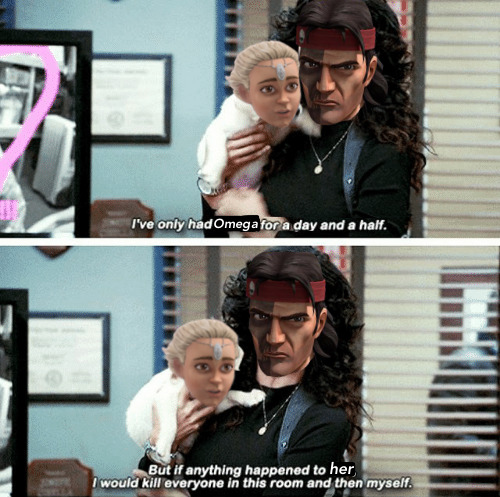

The Bad Batch in a nutshell:

#meme#mine#star wars#the bad batch#tbb#tbb spoilers#not really but just in case#tbb hunter#tbb omega#why are my low effort star wars memes the most popular

182 notes

·

View notes

Text

2017: confusion, hopelessness, and silver linings

Remember on January 1st of 2017 when someone altered the Hollywood sign to say hollyweed? Well I guess we should’ve known the year would be all downhill from there.

Ok that’s not totally fair. On the world stage it was a year of highs and lows, disasters and improvements, and it’s difficult to separate the good from the bad. If I had to sum up my year, I’d label it as in confusion. World events seemed to be one disaster after another all through the year. From a rise in gun violence in the United States, to a humanitarian crisis against the Rohingya people, a catastrophe in Yemen that the rest of the world has ignored to numerous natural disasters across North America, 2017 was a year of suffering across the globe. Not to mention and an increase in oppressive and chaotic policies from world powers: pushback against free speech in China, efforts to curb internet freedom from every major world power in human civilization, Turkey’s embrace of elected dictatorship, the United States’ rollback of protection on transgender individuals, Spain’s takeover of Catalunya, Russia’s imprisonment of political opponents, a genocide against gay people in Chechnya and the United States’ pullback on climate protections. Some claimed 2016 showed a rebellion of the working class against elites, and heralded populist policies as restoring rule of the common person. 2017 showed how misguided these ideas really were.

But in the middle of all the suffering, 2017 showed us a slight glimmer of hope for us to build our futures on. As an observer of humanity, I was very enthusiastic to see the rise and popularity of the #MeToo movement—that a substantial group of people in western society are willing to listen to the claims of women against harassment, and take a stand against anyone who perpetuates this violence. And this new intolerance of sexual crimes even drifted to the most conservative parts of the united states: a (small) majority of Alabama voters were willing to put aside the politically-divisive atmosphere that they’ve cherished in the face of a candidate whose unapologetic bigotry was overshadowed by his alleged pedophilia. After a tense year in most western countries’ politics, this showed some kind of hope that people would stand together to put what is right before their own pride.

Any discussion of 2017’s silver linings would be incomplete if I didn’t mention the strides taken by Saudi Arabia’s crown prince to modernize the countries policies and eliminate corruption. From allowing women to drive, to a reopening of movie theaters, I am hopeful that the oppressive regime will continue its path towards acknowledging human rights to all people. These steps might be small, they may be small victories amidst a larger trend against human rights, but the most oppressed among us are slowly gaining their freedoms. Those people’s livelihoods are worth every struggle. Amidst a general feeling of hopelessness that has surrounded world events, we have a beautiful silver lining. That was a main theme of 2017: hope in the face of hopelessness.

I found it interesting how closely entertainment in 2017 reflected this. Memes became more ironic and cynical as the world seemed to lose its way forward. As life became more confusing and the truth seemed to drift farther away, surreal memes became popular showing the meaningless of the world. Even the newest movie in the Star Wars saga reflected our time, showing how small acts of kindness in the face of huge defeats for the resistance made the whole journey worth it, all while the film’s antihero urges us to put our losses behind us and embrace the uncertainty of the future.

Many of the reactions people had to all this trouble really bothered me, especially people who try to fight what they think is wrong, but aren’t sincere about it. I call it popular protesting, and I know I’ve played along with it sometimes. When there’s some outrage in the world, people speak out about it until its old news, and then they move on to something else. Meanwhile the people affected by the outrage are left to rot, just some pawns in a political game. It’s sick, and it has to stop. Meanwhile people totally ignore crises that are harder to take some fake moral high ground in (again why don’t more people care about the worst humanitarian crisis of the decade in Yemen?).

Of course for us, what makes a year good or bad is more about personal experience than that of world events that don’t affect us personally. And I know a lot of you had amazing years, spending time with friends and making memories. Ironically, I think my year directly mirrored the world’s. Some of the best memories of my life were formed this year, and some of the worst, I felt the general hopelessness and saw silver linings in my own life as in the world. Maybe we’re all just reflections of the world we live in, if we are willing to admit it to ourselves.

At the end of 2016, I asked a friend on Instagram what he thought the key to ethical behavior was. His response was “to accept that you are not any more special than anybody else and act accordingly.” I thought that was a pretty crappy answer at first, but I think he’s right: it takes realizing that you are no superior to anyone else to act in a way that isn’t selfish and act fairly. Everyone is just as confused and scared as you, nobody belongs anywhere, and everyone’s going to die, so you have the same consideration towards all people as you do yourself. So I went into 2017 with that attitude, spent a lot of time thinking about life, and after melding it with my previously-held beliefs, I thought I’d been enlightened or found some sort of key to life. I realize now how arrogant that was to think I had everything in my understanding. I guess if life was easy to figure out, someone else would’ve done it by now.

Here’s the thing. In Atlantis’s culture there’s something called the Jakanta, an ancient practice which refers to a way of living, where you constantly pursue a greater truth, discovering some sort of pattern to the universe. I’m not sure if there’s an allegory in human society but it’s something engrained in our history and I try to live to pursue it. For a long time I felt like I was getting closer to being firmly “enlightened” and gained understanding of reality, and then I came across information that started forcing me to dismantle what I thought were my hard-formed values. The thing is, it was my philosophy of Jakanta that was forcing me out of the ideas I’ve believed my whole life. Realizing that you’ve been wrong and letting go of your so-called sacred cows is probably the scariest thing a person can do. And it didn’t make me happier or feel liberated or anything, it only made my life more chaotic and confusing. Because I loved being that old Hep. That Hep was so passionate and driven, felt wise and validated, like I was going somewhere. I bet if that Hep met me now he would never guess I was once him. Maybe that Hep would rather die than become me, see me as some empty and purposeless shell. But the ironic part is that I came directly from that Hep’s way of thinking.

Anyone who has talked to me at any length knows I’m a more than a little obsessive about the concept of identity (If y’all want, maybe I’ll write a long paper about all I’ve learned about it someday). That’s one of the main reasons I’ve kept my account all these years lol, because constantly being asked who I am by all of you forces me to think about identity and I still don’t have it completely figured out. But this is what 2017 taught me: what defines you isn’t your beliefs or knowledge, because that is constantly changing (either that or you die stupid, like your politicians). Rather I think that what forms a person’s identity is how they think and allow themselves to grow. What are they willing to question? Do they have faith in something? I guess the beliefs that define your identity are the ones about how to grow, not conceptions of the world. So if any of us want to improve, we need to start by adopting a better way of thinking.

So this begs the question, is my way of thinking even good? Obviously questioning and overanalyzing everything like I do didn’t do me any favors, basically destroying whatever walls I’d built up to keep me sane! I feel like after the past year I’ve lost touch with a lot of reality, just drifting through some abstract space I don’t understand. Maybe I’ve gone insane, probably, even. But at least I am authentic to myself. Because it’s so easy to delude yourself, and I’m constantly worried that I’m pushing reality away in exchange for what I’d rather be true to feel secure and accepted. You can convince yourself of anything you want, if it makes you feel good. Maybe if “ignorance is bliss” I should just forget the whole thing and delude myself into whatever is comfortable. For several months I’ve been wrestling with a simple question: if knowing some truth makes me unhappy and sets my life askew, is it worth knowing? I’ve asked a ton of friends about this (thanks y’all). One of them told me what I’d feared: my good friend told me that nobody can never escape ignorance, so learning isn’t relevant. She told me that it’s best to live entirely in faith and not question things that may lead me down questionable paths. My gut reaction was to reject that, but I didn’t understand why. Because she’s right, I will never achieve complete understanding, I know it as did the monks who established the Jakanta in Atlantis 3000 years ago. Was it time to topple that final pillar of my identity and exchange pursuing knowledge for a blissful life?

It took me a while to come up with a good answer: knowledge builds wisdom, and that helps others. A happy life lived only for itself is no meaningful life. However, I can use my understanding of the world to help others who are struggling with similar situations, and not often, but maybe, I can change someone’s life for the better. If I can help just someone, all the unhappiness in the world is worth suffering. How selfish is willful ignorance! Only those who suffer can sympathize with others. That’s why every religion claims their central figure “suffered in every way.” I’m no more special than anyone else, so if I can help someone through real physical struggles, my mental confusion is worth every second of it. So then knowledge doesn’t always make you happy, but it always makes you better.

See I don’t know when I’ll die. I’m just lucky to have survived for as long as I have. I think I don’t value that enough: I need to make a difference while I still can, in the name of those who didn’t make it through the past year. And most importantly, when my time comes I want to die where I stood, following what I believed in. I don’t want to die complacent, like a former hero who has become irrelevant while his work is undone. That’s why I try so hard to keep improving myself, so that I can pursue what I believe till the very end. Life is too short to check out and stop helping people.

I’m realize I’m rambling, and maybe you’re trying to think up some platitude to respond to me, but I assure you that’s the last way I want you to react. This is not at all a plea for sympathy or some way to evangelize my ideas to you, I’m just putting out there what I’m thinking because maybe it will help someone think. And because everyone always asks me what my “true identity” is: well, this is it. I’m Hep, because that’s how I choose to grow.

Is happiness a lost cause for those of us who question everything like I think is right? I thought so at first. But my good friend Taylor made a point that gave me hope: she says that whatever contentment I lost because of what I’ve learned this year will surely pass. Everyone knows that people resist change, that much has been obvious over the last two years. Missing my old state of mind and feeling less happy about life becoming chaotic and confusing is just that same fear of change. If I embrace the chaos, I’ll eventually find that contentment again. I expect this cycle of understanding and confusion will continue throughout my life. Thinking I know myself, losing it, and moving on. Maybe it will bring with it waves of depression or confusion, but all is worth it because with each cycle I will be better equipped to help others. And so out of this cycle of hopelessness and chaos, I have my silver lining.

You know, seems poetic to me that America, in a year full of politically-charged anger, would experience a full solar eclipse. As some of you know, I made the trek out from Atlantis to middle America to see the full eclipse, and maybe those of you who didn’t do the same will not understand this at all. When the full eclipse began, and the sky had darkened, a cold wind rolled over the plains relieving from a hot summer afternoon and the sun became a beautiful iridescent ring, circling a brilliant silver sphere of the moon. It hovered there in the sky, and for a minute it seemed to give peace to everything beneath it. I was reminded of the words of a certain future empress of Atlantis, 19 years old at the time, nearly 2500 years ago. “When nature reveals to us its full glory, it challenges us to imprint its beauty upon our souls.” She said this while leading a rebellion against a violent and oppressive government that ruled Atlantis, a movement which would result in the restructure of our government and issue in an era of prosperity, peace and stability. To me, the eclipse was a reminder that life and society are improved not by opposing anger with anger, but by individuals each harboring a determined peace and understanding as the foundation of their souls.

This thought is by no means original in the current climate, but while these ideas are often used as tropes to make the user feel righteous they are blatantly ignored in practice. Maybe many of them try to live by it. I know I’ve failed at applying this idea many times, because anger is such an easier response to fear and confusion than temperance and self-examination. It is my challenge to keep improving myself to approach this, and I expect I will continue pursuing this goal for the rest of my life.

I’m not a believer in new years resolutions. You can keep your “new year new me” crap, because one week in, you’ll realize you have no means to achieve your goals, give up and be twice the slob you were beforehand. Heck I bet a handful of you already gave up. Because you can’t just change your habits and beliefs on a whim, all you can hope to do is make an effort to grow. So in that spirit I’m giving myself a challenge to give myself a direction to improve. I probably will fail to follow it many times, but that’s okay as long as I keep trying.

Here’s my challenge, to start the year. For one, I’m not going to fall into the trap of popular protesting. If something bad is going on, I’ll either keep spreading awareness and don’t stop until it’s fixed—no letting go when the public stops caring—or I’ll let someone else carry the fight. There’s nothing worse than an insincere activist. And if someone is being unethical it does me no good to hate on them. The best reaction is to behave in the way opposite of them, acting positively instead of negatively. As my man Ghandi once said, you gotta be the change you wish to see in the world. I think I’m going to try to cut judgement out of my life altogether: whenever something happens or someone says an idea, my first reaction is often to identify it as good or bad. Just like I’m not a fan of names, I’m not a fan of those labels, and I’ll work to stop that response in myself. Every time you label something, you keep it from being properly questioned, and that’s unhealthy for me. And finally, as always, I will try to be a decent person, try to make an impact on those around me and work to acquire knowledge and improve my thinking.

That’s where I’m going in the next year. I’m not asking you to agree with it or adopt the same challenge, but I hope you ask yourself where you want to grow. Every day is another step in the journey to make yourself authentic, and I hope you all live to be the best versions of yourselves. Don’t be afraid to leave your pasts behind and look to the future, always find ways to be kind, and never stop questioning your thoughts.

Hep out.

3 notes

·

View notes

Link

The age of “fake news” is coming for film criticism.

The new Gotti, which stars John Travolta as the infamous mob boss, seems like a solid contender for the title of worst movie of the year. Technically, it premiered at Cannes — if by “premiered” you mean “had a screening almost no press attended in the smallest theater at the Palais” — and garnered abysmal reviews from the critics who were there.

It then screened for a very small set of critics (I was not invited to any screenings), who found it so awful that it wound up with the rare 0 percent score on Rotten Tomatoes and a damning-by-faint-praise 24 on Metacritic.

But the film’s marketers have fought back, launching an offensive that doesn’t just suggest but outright accuses critics of mounting a coordinated hit on the movie.

In all likelihood, it’s just a marketing tactic for a silly movie, and it will have little, if any, effect on either the film’s bottom line or the field of movie criticism. Yet the tactics lurking behind the Gotti campaign bear an eerie resemblance to the much larger problem of “fake news” in our time.

Looking at Gotti is like staring through the wrong end of a telescope and seeing everything you need to know about “truth” on the internet, only in microcosm and applied to the least important thing imaginable: a bad movie.

“Fake news” started out as a term to describe sensationalized, fabricated stories concocted for profit. But it was quickly co-opted by Donald Trump and his followers as a lazy slur to sling at any story he didn’t like, something he’s outright admitted. “Fake news” is shorthand for “this story doesn’t paint me in a good light.”

That’s the Gotti ad method, too:

Audiences loved Gotti but critics don’t want you to see it… The question is why??? Trust the people and see it for yourself! pic.twitter.com/K6a9jAO4UH

— Gotti Film (@Gotti_Film) June 19, 2018

In case you didn’t finish watching the video, here’s what it says:

AUDIENCES LOVED GOTTI.

CRITICS PUT OUT THE HIT.

WHO WOULD YOU TRUST MORE?

YOURSELF OR A TROLL BEHIND A KEYBOARD

For critics, it’s pretty impossible to watch this without chuckling. (The aforementioned “troll behind a keyboard” definitely describes a lot of the people who show up in your Twitter mentions if they don’t like your opinion about a film.)

But it’s a good template for how to get the “fake news” claim to stick. First, it’s important to cast doubt on the trustworthiness of the people generating the stories and opinions you find objectionable. Do it over and over again. Call them “disgusting” and challenge their right to exist.

And don’t forget to suggest that there’s a conspiracy afoot. “Put out the hit” doubles as a clever topical metaphor for a movie about a crime boss and an implication that critics get together in shadowy, secret back rooms at family restaurants and plot to take down movies over cigars and grappa. We wish!

People like believing conspiracy theories because they seem to make sense of a confusing world and they’re impervious to attempts to refute them. And there are lots of conspiracy theories about film critics, the most popular being that we’re paid by Disney, which owns Marvel Studios, to give negative reviews to DC films.

Gotti is playing right into an idea that some people already believe, though the ad doesn’t bother to suggest any plausible reason critics would bother to “put out a hit” on a film so small most people didn’t see it.

Finally, suggest that the purveyors of whatever you’re deeming “fake news” right now are out of touch with or outright harmful to “real” people, ordinary agenda-less folks whose opinions are by default better than “elites.” This is a time-honored tactic for stars in blockbusters who don’t like what they read about their films.

For instance, here’s Samuel L. Jackson after the 2012 release of The Avengers:

#Avengers fans,NY Times critic AO Scott needs a new job! Let’s help him find one! One he can ACTUALLY do!

— Samuel L. Jackson (@SamuelLJackson) May 3, 2012

And here’s Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson after the release of Baywatch, which only netted a score of 18 percent on Rotten Tomatoes:

That kind of populist appeal works on some people for the same reason it works in politics: There’s a sizable group of people who harbor resentment against anyone they think of as looking down on them.

When film critics trash a movie that audiences like, they generally aren’t thinking of the audience. But we sometimes get feedback on those reviews that implies the reader is going to “own” us by going to see the film. I don’t care if you go see the film to which I gave a bad review, nor does any other critic I know. But that kind of reply shows a common perception — and marketers and stars know how to use that perception to their advantage.

If you can get people to doubt the sources, convince them there’s a conspiracy theory afoot, and suggest that the “fans” are obviously more correct than the critics, then you may just succeed in getting more people in the door at the movie theater — and that’s the whole idea.

Gotti went for the full three-pronged approach. The first two are impossible to argue with. I can’t convince you that I’m trustworthy, and no other critic can either — that’s the nature of the opinion-giving business. All you can do is read my writing and decide if you like it. And I can’t prove to you that we’re not conspirators, except to say that if you’ve ever known a group of film critics you’d know how funny the idea of us organizing anything at all is.

The third prong is tough to argue with, too. But in the case of Gotti, there’s an extra layer.

The idea that “audiences” loved Gotti was supported by the audience score on Rotten Tomatoes, which as of today is at 61 percent. But there are two reasons to raise an eyebrow.

First, the audience score on Rotten Tomatoes is all but useless. It can, and has, been gamed by groups like the alt-right and angry fans to drive down audience scores for films they deemed objectionable, like Black Panther, The Last Jedi, and Ghostbusters. Anyone can rate a film, whether or not they’ve seen it — and that means sometimes films’ audience scores can be inflated or deflated before the film has even released in theaters.

Even if the site required the user to prove they’d seen the film, though, there’s still a flaw: Audience scores by nature reflect the opinions of people who were inclined enough to see a movie (through interest in the subject matter, perhaps, or the star, or successful marketing efforts), to buy a ticket and give up a couple of hours of their day to see it. So there’s a natural curve built into the audience score.

What audience scores at their best measure is what Cinemascore more or less measures: How much people who already wanted to see the film liked it. But critics don’t get that choice, and thus there’s more granularity built into their opinions.

But there’s one more wrinkle in the case of Gotti. There might be something fishy about the audience score.

First of all, it’s made up of more than 7,000 ratings, which is a remarkably high number for a film that only made $1.7 million on its opening weekend in 503 theaters (which implies a relatively low number of people in the audience). By contrast, Incredibles 2 made more than $183 million in 4,410 theaters and only has a little more than 8,000 audience ratings on Rotten Tomatoes. And Hereditary, which opened with more than $13 million in 2,964 theaters, has 5,529 ratings on the site.

Sure, it’s possible that Gotti fans are just extremely vocal and passionate about the film. But according to some people who dug through the data, it certainly looks like a number of the user accounts are very new users of Rotten Tomatoes. And while there could be a logical, non-shady explanation for that, there are other explanations, too, that have to do with someone rigging the system. (Rotten Tomatoes, for its part, stands by the score and claims there was no manipulation.)

Once again, herein lie shades of our age of “fake news”: the suspicion that trolls and bots are manipulating our “reality,” first online and then offline, too. There are the Russian “troll farms” that produced truly fake news and weaponized our social media feeds and fake Reddit accounts that have had to be shut down and a lot, lot more. So it seems almost inevitable that whether or not they’re messing with the Gotti score to pump up the film’s visibility, trolls and bots will be part of the mess of audience scores some day soon.

It is very, very hard to tell if any of this is in good faith. Are the people behind the Gotti campaign earnest about their silly claims, or are they just trying to get a rise out of people in order to raise the film’s visibility?

This question extends to the audience reviews left on Rotten Tomatoes, which are pretty wild:

Trolling and shitposting are complicated, but they’re everywhere — weaponizing irony and “comedy” and memes and jokes to both exact some kind of revenge by making your enemy look foolish and confuse them into dismissing you.

That’s not to say that the alt-right is involved in this whole Gotti deal, though anecdotal evidence shows that there may be some overlap between the #MAGA crowd and Gotti fans.

(MoviePass owns a 40 percent stake in Gotti.)

But the fact that we cannot even figure out if this ad campaign and the Rotten Tomatoes score are real feels very of a piece with everything in our fake news world. Call the critics fake news and stoke a conspiracy theory. Game the system through possibly shady tactics. And do it all in an environment where it’s totally possible to just say “we were kidding!” if you somehow get caught.

Gotti doesn’t really matter, and neither does its goofy ad campaign. But it’s a little depressing to see the things many of us worry about in the all-important spheres of policy and politics seeping into something as inconsequential as a terrible movie about a mob boss.

Original Source -> The John Travolta Gotti movie is waging a Trump-style war on critics

via The Conservative Brief

0 notes

Text

Meet Rupi Kaur, Queen of the 'Instapoets'

New Post has been published on http://gossip.network/meet-rupi-kaur-queen-of-the-instapoets/

Meet Rupi Kaur, Queen of the 'Instapoets'

Rupi Kaur is too sick to get out of bed and wishes she had realized this a few hours earlier. Sitting on a king-size mattress in her Soho Grand hotel room, Kaur tells the story of how she almost lost her brunch all over actress Jennifer Westfeldt. “I knew something was wrong when I was talking to Jennifer and the green haze came over me,” she says in between sips of red Gatorade. “I was like, ‘You’re talking about something so deep right now, but the strawberries are coming back up girl, I gotta go.'”

Trying to keep fruit down isn’t exactly how the 25-year-old imagined she’d be celebrating the release of her second collection of poetry, The Sun and Her Flowers. It’s a celebration which kicked off the night before with a live performance of her work featuring Westfeldt, YouTube star Lilly Singh and fellow poet Chloe Wade. But this story of what was supposed to be a nausea-free victory lap, which she spares me the gross details of finishing, is just the kind of anecdote her 1.9 million Instagram followers would adore.

Since 2013, Kaur has been sharing poems about love, heartbreak and womanhood that perfectly exemplify the self-care movement. Most are bite-size affirmations, accompanied by Kaur’s own delicate line drawings, that go down easy when scrolling through Instagram. Kaur’s most-liked poem, which is just six lines and begins “how is it so easy for you/ to be kind to people, he asked,” earned over 240,000 likes.

Her poetry has gotten her more than likes, though. Her debut, Milk and Honey, has sold more than 2.5 million copies worldwide since its 2015 re-release by Andrews McMeel Publishing. (Kaur self-published it a year prior.) In its first week of release, Kaur’s follow-up was duking it out for the top spot on Amazon’s best-seller list with Dan Brown’s latest novel. It would win the coveted spot atop The New York Times list for paperback trade fiction where it stayed for nine straight weeks before E.L. James usurped it.

Uncomplicated and concise, Kaur’s poetry has been criticized for being too simplistic. Parody accounts have shown up on Twitter that intend to show how easy it is to write a Rupi Kaur poem – the gist being you take any conversation, format it in all lowercase and insert random line breaks. Milk and Honey officially became a meme earlier this year when people starting taking the text from Vine videos and stylizing them like one of her poems. Now there’s even a book called Milk and Vine that’s quickly become an Amazon bestseller since its October release.

Kaur doesn’t think her poetry is simple. To her, it’s straightforward. “It’s like a peach,” she says. “You have to remove everything and get to the pit of it.” Kaur – who moved from Punjab, India to the suburbs of Ontario, Canada, when she was three and a half years old and now lives in Toronto – doesn’t want readers to agonize over each and every word like she did when learning poetry in school. “I would have to pull out the list of literary devices my teacher gave me and my 10 colorful pens,” she says, her big, almond eyes getting wider. “It was like doing surgery on the damn thing.”

Instead, Kaur wanted to do something more accessable. “I’ve realized, it’s not the exact content that people connect with,” she says. “People will understand and they’ll feel it because it all just goes back to the human emotion. Sadness looks the same across all cultures, races, and communities. So does happiness and joy.”

Though she’s made her name with words, Kaur’s initial Instagram fame had nothing to do with her poetry. Three years ago, Kaur posted a shot of herself lying in a bed with her back to the camera, menstrual blood leaking through her sweatpants. Instagram removed the image – which was for a college assignment in which she was asked to “challenge a taboo” – two separate times for breaking community guidelines. The site eventually apologized and reposted the photo, but not before Kaur wrote a letter reprimanding them for trying to censor her. “Their patriarchy is leaking. Their misogyny is leaking. We will not be censored,” she wrote on Facebook, in a post that’s been shared over 18,000 times.

Kaur’s response went viral and soon she was doing interviews with The Huffington Post and Vice about the need to “demystify the period.” Talking to Kaur now, she says she wishes she never wrote that letter – curious, since that’s how so many people found her Instagram. “I think that day, this anxiety came upon me that’s never left,” she says, recalling how scary it was to get “that much hate literally from every corner of the planet.” While Kaur says she received overwhelming support from the letter – the most memorable, she says, was an email from a war general in Afghanistan – she also never experienced “so many people saying so many mean things and telling me they were going to kill me.” Still, she doesn’t deny that the strongly worded letter benefited her career: “They came for the photo, but they stayed for the poetry.”

Why they stayed is simple, according to Kirsty Melville, the president and publisher of Andrews McMeel Publishing, which had previously been best known for releasing Calvin and Hobbes. “She’s given voice to things that people may not have been able to articulate for themselves,” she says. “In this digital world where content marketing is this sort of buzzword, Rupi is the content and it doesn’t need the marketing.”

Kaur’s popularity on Instagram is part of a trend so prominent in publishing right now that it’s spawned its own genre. “Instapoets” has become the term used to describe a new generation of writers including Lang Leav, Tyler Knott Gregson, Nayyirah Waheed and Robert M. Drake, all of whom have landed book deals thanks to their respective social media presence. “We were told for so long that there isn’t a market for this, and there is,” Kaur says. “I’m seeing so many more poets who are getting published, which I hope isn’t just a trend that goes away.”

Instagram, Tumblr, Facebook and Twitter have allowed more poets – especially those of color – to share their work with a larger, younger and more diverse audience, but not everyone loves the “Instapoets” nickname. “Personally, I think it is ridiculous that a social media platform is used to define a genre of writing,” says Leav, who has 393, 000 Instagram followers. After all, Leav released her first two bestselling poetry collections – her 2014 self-published debut, Love & Misadventure, which sold 10,000 copies in the first month, and Lullabies, which was published that same year by Andrews McMeel – without ever writing a word on Instagram. (She preferred Tumblr.)

No two Instapoets are exactly alike, but there are similarities between writers that even those in the community find worrisome. Earlier this year, Waheed, who self-published her debut, Salt, a year before Milk and Honey, accused Kaur of “hyper-similarity” after fans on Twitter and Tumblr made those charges. Waheed wrote in a Tumblr post, which has since been taken down, that in 2014 she emailed Kaur, “woc writer to fellow woc writer,” to share her concerns “in the hopes that upon awareness on their part. efforts would be made to cease and desist.” In the post, Waheed, who keeps a low public profile, rarely giving interviews, said that her concerns went ignored.

Kaur declines to comment on Waheed’s specific allegations, but when speaking in her hotel room says she believes some crossover between poets is natural when they have “similar experiences and similar ideas about the world.” She also wonders if some of the accusations of similarity between her work and others are a way of silencing women of color. “It’s like that scarcity complex,” Kaur says. “‘We already have one and it’s enough,’ as if we have to fight each other off now and I think that’s really dangerous.”

Over 900 fans came out to see Kaur read at the Tribeca event.

John Halpern

Kaur certainly isn’t spending her time duking it out with other poets. She holds her own unique space in the literary world where her poetry readings are more like pop concerts. To launch The Sun and Her Flowers, she put on a special theatrical performance at the Tribeca Performing Arts Center in New York City to a sold-out crowd of over 900 people willing to shell out $75 to $100 to see her.

In a nod to the book’s cover, Kaur’s fans – mostly women in their late teens and early twenties – took photos with gigantic sunflowers. Beyoncé, Rihanna and Drake played over the speakers before the petite poet took the stage in a dress that hit right above the knee. It was something that gave her pause, knowing that her Sikh father was in the audience. “It’s the shortest thing I ever wore in front of him,” Kaur says later. “I was like, ‘My legs! He’s never seen my legs before!'”

When Kaur speaks, her fans, which she says are “60 percent female and 40 percent everything else,” listen. They also whoop and holler when she delivers the climax of her most suggestive poem, Milk and Honey‘s “How We Make Up”: “Sweet baby, this is how we pull language out of one another with the flick of our tongues.” They snap their fingers in solidarity after “What’s stronger than the human heart/ that shatters over and over and still lives,” a line that found its way onto posters at the Women’s March in January.

“Whenever I read her poems, I have the same thought: ‘This is exactly how I feel but never knew how to say it,'” Lilly Singh writes in an email days after sharing the stage with Kaur to read selections from The Sun and Her Flowers. “Rupi’s words make people, especially women, feel safe and understood.”

Kaur has no problem connecting with her audience, but now she’d like the literary world to take her more seriously. She admits that her goal with her new collection was to improve as a writer and show “that just because your work is successful does not make it bad work.”

Kaur started writing Milk and Honey when she was 18. Now 25, Kaur doesn’t deny that she’s outgrown some of her early work, but isn’t ashamed of anything she’s put down on paper. “We grew up in a time with every single one of our moves being recorded and documented forever and in that was this idea that we can’t make mistakes,” she says, “but when that’s not happening you’re also not growing.”

The way she looks back at her life and lets her fans know it gets better is a big part of Kaur’s appeal, but some critics question whether the stories in her work are really hers to tell. Kaur’s been criticized for blurring the lines between her own experiences and the experiences of others when writing about the trauma women face – rape, sexual assault, domestic abuse – most notably in the Buzzfeed piece “The Problem With Rupi Kaur’s Poetry.” The essay makes the case that the poet’s “use of collective trauma in her quest to depict the quintessential South Asian female experience” is a way of forcing universality to reach a larger, more mainstream audience. It’s a dilemma that many writers of color face, knowing that sticking with specifics in regards to their own story could mean alienating readers.

Kaur tells me she writes about the South Asian experience – hers, her friends’, her family’s – because she doesn’t want to see these stories go untold. “I began writing pieces about violence at the age of 16 after seeing what the women around me were enduring and facing,” Kaur says. “It was my way of reflecting on all of these issues.”

With so little South Asian representation in entertainment, Kaur also understands how important it is for her to share these stories even if it may come with some backlash. “This name,” she says, pointing to the “Kaur” that appears on the binding of her latest book, which she pulls out from underneath the white comforter of her hotel bed, as if scripted, “is so important on a bookshelf. That’s the name of every Sikh woman. If I was six years old and I saw this in Barnes and Nobles, I would cry. I would sit there and be like, ‘If she can do it, I can do it.'”

With Sun and Her Flowers, Kaur’s still following her peach-pit philosophy, but she’s also getting at the core of who she is, delving deeper into her South Asian identity in a section of the book fittingly called “Roots.” The eldest of four writes at length about her parents, specifically her mom, whose struggle with being an immigrant is something Kaur admits she’s often taken for granted.

During her Tribeca performance, Kaur tells a story about how, as a kid, she would ignore her mom at the supermarket, too embarrassed by her accent to be seen with her. The anecdote acts as the perfect lead-in to “Broken English,” the standout of her latest collection in which she chastises herself and anyone else who’s ever been ashamed of their immigrant mother. “She split through countries to be here/ so you wouldn’t have to cross a shoreline,” she writes. “Her accent is thick like honey/ hold it with your life/ it’s the only thing she has left of home.”

The funny thing is, Kaur almost didn’t include this section in her book. “I thought nobody cares about this,” she says. “It’s not cool to talk about your parents.” But it’s the part that’s gotten the most feedback from fans who want to tell Kaur about their own mothers and how far they traveled for a better life. “When you start writing those other poems about your parents and all that, it’s like, how can you write about love and heartache?” Kaur asks. “That just seems so silly.”

For those who want it, there are still plenty of traditional love and heartache poems in The Sun and Her Flowers, but Kaur’s expanding on these topics. She’s now writing more authoritatively about the love and heartache that accompanies her mom and dad’s immigrant story and discovering that her specific experience of being a woman, being Punjabi and being a child of immigrants has universal appeal.

Knowing how far her reach is, Kaur doesn’t just want to write poetry, but prose, too. Back in 2015, she wrote 10 chapters of a novel that she’s still figuring out what to do with. She’s also thinking she might even want to give music a try. “It would be cool to write a song with Adele,” Kaur mentions with a chuckle. “You know, if she calls me up.”

Source link

0 notes

Link

The age of “fake news” is coming for film criticism.

The new Gotti, which stars John Travolta as the infamous mob boss, seems like a solid contender for the title of worst movie of the year. Technically, it premiered at Cannes — if by “premiered” you mean “had a screening almost no press attended in the smallest theater at the Palais” — and garnered abysmal reviews from the critics who were there.

It then screened for a very small set of critics (I was not invited to any screenings), who found it so awful that it wound up with the rare 0 percent score on Rotten Tomatoes and a damning-by-faint-praise 24 on Metacritic.

But the film’s marketers have fought back, launching an offensive that doesn’t just suggest but outright accuse critics of mounting a coordinated hit on the movie.

In all likelihood, it’s just a marketing tactic for a silly movie, and it will have little, if any, effect on either the film’s bottom line or the field of movie criticism. Yet the tactics lurking behind the Gotti campaign bear an eerie resemblance to the much larger problem of “fake news” in our time.

Looking at Gotti is like staring through the wrong end of a telescope and seeing everything you need to know about “truth” on the Internet, only in microcosm and applied to the least important thing imaginable: a bad movie.

“Fake news” started out as a term to describe sensationalized, fabricated stories concocted for profit. But it was quickly co-opted by Donald Trump and his followers as a lazy slur to sling at any story he didn’t like, something he’s outright admitted. “Fake news” is shorthand for “this story doesn’t paint me in a good light.”

That’s the Gotti ad method, too:

Audiences loved Gotti but critics don’t want you to see it… The question is why??? Trust the people and see it for yourself! pic.twitter.com/K6a9jAO4UH

— Gotti Film (@Gotti_Film) June 19, 2018

In case you didn’t finish watching the video, here’s what it says:

AUDIENCES LOVED GOTTI.

CRITICS PUT OUT THE HIT.

WHO WOULD YOU TRUST MORE?

YOURSELF OR A TROLL BEHIND A KEYBOARD [sic]

For critics, it’s pretty impossible to watch this without chuckling. (The aforementioned “troll behind a keyboard” definitely describes a lot of the people who show up in your Twitter mentions if they don’t like your opinion about a film.)

But it’s a good template for how to get the “fake news” claim to stick. First, it’s important to cast doubt on the trustworthiness of the people generating the stories and opinions you find objectionable. Do it over and over again. Call them “disgusting” and challenge their right to exist.

And don’t forget to suggest that there’s a conspiracy afoot. “Put out the hit” doubles as a clever topical metaphor for a movie about a crime boss and an implication that critics get together in shadowy, secret back rooms at family restaurants and plot to take down movies over cigars and grappa. We wish!

People like believing conspiracy theories, because they seem to make sense of a confusing world, and they’re impervious to attempts to refute them. And there are lots of conspiracy theories about film critics, the most popular being that we’re paid by Disney, which owns Marvel Studios, to give negative reviews to DC films. So Gotti is playing right into an idea that some people already believe, though the ad doesn’t bother to suggest any plausible reason critics would bother to “put out a hit” on a film so small most people didn’t see it.

Finally, suggest that the purveyors of whatever you’re deeming “fake news” right now are out of touch with or outright harmful to “real” people, ordinary agenda-less folks whose opinions are be default better than “elites.” This is a time-honored tactic for stars in blockbusters who don’t like what they read about their films.

For instance, here’s Samuel L. Jackson after the 2012 release of The Avengers:

#Avengers fans,NY Times critic AO Scott needs a new job! Let’s help him find one! One he can ACTUALLY do!

— Samuel L. Jackson (@SamuelLJackson) May 3, 2012

And here’s Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson after the release of Baywatch, which only netted a score of 18 percent on Rotten Tomatoes:

That kind of populist appeal works on some people for the same reason it works in politics: there’s a sizable group of people who harbor resentment against anyone they think of as looking down on them. When film critics trash a movie that audiences like, they generally aren’t thinking of the audience. But we sometimes get feedback on those reviews that implies the reader is going to “own” us by going to see the film. I don’t care if you go see the film to which I gave a bad review, nor does any other critic I know, but that kind of reply shows a common perception — and marketers and stars know how to use that perception to their advantage.

If you can get people to doubt the sources, convince them there’s a conspiracy theory afoot, and suggest that the “fans” are obviously more correct than the critics, then you may just succeed in getting more people in the door at the movie theater — and that’s the whole idea.

Gotti went for the full three-pronged approach. The first two are impossible to argue with. I can’t convince you that I’m trustworthy, and no other critic can either — that’s the nature of the opinion-giving business. All you can do is read my writing and decide if you like it. And I can’t prove to you that we’re not conspirators, except to say that if you’ve ever known a group of film critics you’d know how funny the idea of us organizing anything at all is.

The third prong is tough to argue with, too. But in the case of Gotti, there’s an extra layer.

The idea that “audiences” loved Gotti was supported by the audience score on Rotten Tomatoes, which as of today is at 61 percent. But there are two reasons to raise an eyebrow.

First, the audience score on Rotten Tomatoes is all but useless. It can, and has, been gamed by groups like the alt-right and angry fans to drive down audience scores for films that are deemed objectionable, like Black Panther, The Last Jedi, and Ghostbusters. Anyone can rate a film, whether or not they’ve seen it — and that means sometimes films’ audience scores can be inflated or deflated before the film has even released in theaters.

Even if the site required the user to prove they’d seen the film, though, there’s still a flaw: audience scores by nature reflect the opinions of people who were inclined enough to see a movie (through interest in the subject matter, perhaps, or the star, or successful marketing efforts) to buy a ticket and give up a couple of hours of their day to see it. So there’s a natural curve built into the audience score. What audience scores at their best measure is what Cinemascore more or less measures: how much people who already wanted to see the film liked it. But critics don’t get that choice, and thus there’s more granularity built into their opinions.

But there’s one more wrinkle in the case of Gotti. There might be something fishy about the audience score.

First of all, it’s composed of more than 7,000 ratings, which is a remarkably high number for a film that only made $1.7 million on its opening weekend in 503 theaters (which implies a relatively low number of people in the audience). By contrast, Incredibles 2 made more than $183 million in 4,410 theaters and only has a little more than 8,000 audience ratings on Rotten Tomatoes. And Hereditary, which opened with more than $13 million in 2,964 theaters, has 5,529 ratings on the site.

Sure, it’s possible that Gotti fans are just extremely vocal and passionate about the film. But according to some people who dug through the data, it certainly looks like a number of the user accounts are very new users of Rotten Tomatoes. And while there could be a logical, non-shady explanation for that, there are other explanations, too, that have to do with someone rigging the system. (Rotten Tomatoes, for its part, stands by the score and claims there was no manipulation.)

Once again, herein lie shades of our age of “fake news”: the suspicion that trolls and bots are manipulating our “reality,” first online and then offline, too. There are the Russian “troll farms” that produced truly fake news and weaponized our social media feeds and the fake Reddit accounts that have had to be shut down and a lot, lot more. So it seems almost inevitable that whether or not they’re messing with the Gotti score to pump up the film’s visibility, trolls and bots will be part of the mess of audience scores some day soon.

It is very, very hard to tell if any of this is in good faith. Are the people behind the Gotti campaign earnest about their silly claims, or are they just trying to get a rise out of people in order to raise the film’s visibility?

This question extends to the audience reviews left on Rotten Tomatoes, which are pretty wild:

Trolling and shitposting are complicated, but they’re everywhere — weaponizing irony and “comedy” and memes and jokes to both exact some kind of revenge by making your enemy look foolish and confuse them into dismissing you.

That’s not to say that the alt-right is involved in this whole Gotti deal, though anecdotal evidence shows that there may be some overlap between the #MAGA crowd and Gotti fans.

(MoviePass owns a 40 percent stake in Gotti.)

But the fact that we cannot even figure out if this ad campaign and the Rotten Tomatoes score is real feels very of a piece with everything in our fake news world. Call the critics fake news and stoke a conspiracy theory. Game the system through possibly shady tactics. And do it all in an environment where it’s totally possible to just say “we were kidding!” if you somehow get caught.

Gotti doesn’t really matter, and neither does its goofy ad campaign. But it’s a little depressing to see the things many of us worry about in the all-important spheres of policy and politics seeping into something as inconsequential as a terrible movie about a mob boss.

Original Source -> The John Travolta Gotti movie is waging a Trump-style war on critics

via The Conservative Brief

0 notes