#women warriors

Text

"Dr Sarah Stark, a human skeletal biologist at Historic England, said the findings provided “evidence of a leading role for a woman in warfare on iron age Scilly.”

“Although we can never know completely about the symbolism of objects found in graves, the combination of a sword and a mirror suggests this woman had high status within her community and may have played a commanding role in local warfare, organising or leading raids on rival groups.”

Stark added: “This could suggest that female involvement in raiding and other types of violence was more common in iron age society than we’ve previously thought, and it could have laid the foundations from which leaders like Boudicca would later emerge.”"

#warriors#history#women in history#warrior women#women warriors#women's history#iron age#archeology#england#english history

424 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Éowyn

‘A sword rang as it was drawn. “Do what you will; but I will hinder it, if I may.”’

I painted this back in November 2017, on the kind request of Will o' Wisps for John Howe’s visit to AthensCon 2017. I had the good fortune to meet him there and give him a print of it. He had very kind words about it, leaving me on cloud nine, because Howe is one of my earliest art heroes.

The Lord of the Rings has very few women characters in it, something that has been the point of criticism almost from its publication in the 50s. It might be for this reason that Éowyn stood out for me, but also because I was moved by how much understanding Tolkien showed for her situation. When she wants to go to war, she is dissuaded by Aragorn, and is rightly bitter about it:

‘She answered: "All your words are but to say: you are a woman, and your part is in the house. But when the men have died in battle and honour, you have leave to be burned in the house, for the men will need it no more. But I am of the House of Eorl and not a serving-woman. I can ride and wield blade, and I do not fear either pain or death."

"What do you fear, lady?" he asked.

"A cage," she said. "To stay behind bars, until use and old age accept them, and all chance of doing great deeds is gone beyond recall or desire.”’

Tolkien gave Éowyn a voice, and not only that, but also a chance to prove her valour and to change the course of the history of Middle Earth as no one else but her could have. He wrote little of women, it’s true. The little he did write, though, was with deep humanity.

#Éowyn#eowyn#eilidh#eleni tsami#lotr#the lord of the rings#women in armor#women warriors#fantasy#Illustration#digital painting#tolkien

418 notes

·

View notes

Text

Luis Royo

225 notes

·

View notes

Photo

𝒃𝒍𝒐𝒏𝒅𝒆 𝒘𝒐𝒎𝒆𝒏 𝒊𝒏 𝒂𝒓𝒎𝒐𝒖𝒓

#bbc morgause#bbc merlin#alice in wonderland 2010#tim burton's alice in wonderland#emilia fox#mia wasikowska#brienne of tarth#game of thrones#gwendoline christie#rings of power#rop galadriel#commander galadriel#morfydd clark#blonde women in armour#women warriors#women in armor#silver armour#fantasy aesthetic#medieval aesthetic#medieval fantasy#women in medieval fantasy#badass female characters#women with swords

758 notes

·

View notes

Text

I love historical figures who sound like anime protagonists

219 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ukrainian Hero

The Ukrainian combat medic Sergeant Daria Filipieva has been killed in battle against the Russian Army.

She was assigned the call sign "Lightning" because she could come to the aid of soldiers as quickly as a bullet or a fragment of a projectile.

Daria, a bright and creative individual, could not stand by and watch others defend their native land. She saved dozens of lives on the battlefield, like an angel. Her light will continue to shine from the sky forever.

Rest in Peace Daria, Ukraine will never forget your sacrifice!

#ukraine#russia#russian war on ukraine#Daria Filipieva#kia#killed in action#killed in battle#killed in war#war#world at war#women warriors#women in combat#combat#battle#fighting#peace#peace for all#peace for ukraine#rest in peace#rest in heaven#rest in paradise#sad

313 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ryber Fortiza, Sightwitch by Nipuni

775 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gun Model/Former US Marine Bree Bunten

101 notes

·

View notes

Text

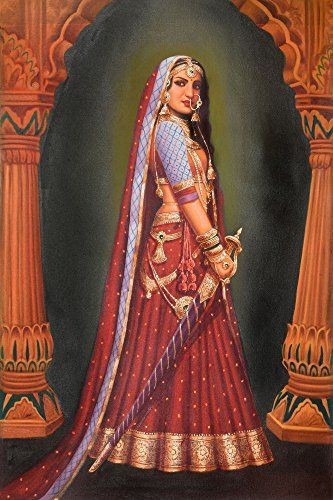

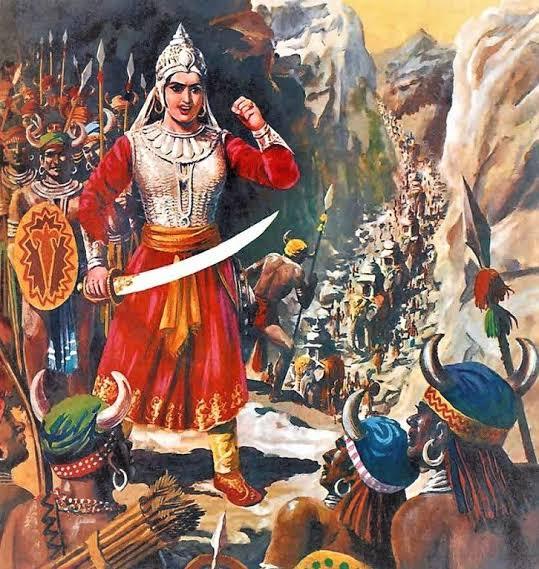

Maharani Durgavati

Durgavati was the daughter of King of Bundelkhand, married to Raja dalpad of Gondwana, in Madhaya Pradesh.

Soon, tragically Raja died and Queen Durgavati with her 5 year old toddler stepped up to the throne. She managed the whole kingdom exceptionally well, as recorded by Akbar’s historian. The kingdom did not suffer any major setback even after their king died.

Gondwana was a rich kingdom, with a beautiful queen which became the target of the Mughals. They didn't wanted to simply take the kingdom under their control, the commander Asaf Khan also “wanted to touch the beauty of Gondwana”.

In 1564, Asaf Khan marched with 10,000 cavalries towards Gondwana, Rani Durgavati marched with 5,000 men to the battlefield.

She led the army well and killed about 500 enemies, she came out victorious by the end of the day, later she purposed to “surprise attack” the enemies or “Gorilla Attack” but none of the council members agreed to that.

By the next morning, Asaf Khan’s army was in a much better place and the fighting continued for 3 exhausting days. By that time only 200 of her men were left but the thought of giving up never once crossed her mind. Her bravery and courage never wavered.

During the battle, one arrow pierced her temple and another pierced her neck, causing her to lose consciousness. When she opened her eyes, the inevitable defeat was clear.

Instead of falling in the hands of men that had nothing but lust for her and would eventually throw her in Harem with other women, that previously were queens of conquered kingdoms that Mughals kept as sex slaves, she took our her dagger and killed herself to save her honor and prevent invaders from doing heinous things to her body, her martyrdom day (24 June 1564) is commemorated as “Balidan Diwas”.

The Mughal army then marched to the fort to loot it's treasure. They found staggering amount of gold pots full of gold, jewels, expensive stones etc.

When they opened a room, it was full of burnt bodies of women that commited Jauhar upon hearing the news of Rani’s defeat. These women committed Jauhar to save their honor and to prevent the Mughals from taking them as sex slaves, unfortunately 2 women were still alive, stuck behind a large wooden block that saved their lives. These two women were then taken to Akbar's court and predictably put into Harem.

#rani durgavati#india#mughal empire#gondwana#indian queen#indian history#madhaya pradesh#forgotten bharat#female warriors#women warriors#queens of india#hinduism#pseudo secularism#hindu kingdom#mughal invasion

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Women warriors in Chinese history - Part 2

(Part 1)

"However, court confessions, unofficial histories, and local gazetteers do reveal a host of women warriors during the Qing dynasty when patriarchal structures were supposedly most influential. Women in marginal groups were apparently not as observant of mainstream societal gender rules. Daughters and wives of “peasant rebels,” that is, autonomous or bandit stockades, were frequently skilled warriors. Miss Cai 蔡†(Ts’ai) of the Nian (Nien) “army,” for example, “fought better than a man, and she was especially fine on horseback. She was always at the front line, fighting fearlessly despite the large number of government troops.” According to a folktale, she managed to rout an invading government force of several thousand with a hundred men and one cannonball after her husband led most of the Nian off to forage for food.

Related to the female bandits were the women pirates among whom Zheng I Sao 鄭一嫂†(literally, Wife of Zheng I; 1775–1844) is the best researched. “A former prostitute … Cheng [Zheng] I Sao could truly be called the real ‘Dragon Lady’ of the South China Sea.” Consolidating her authority swiftly after the death of her husband, “she was able to win so much support that the pirates openly acclaimed her as the one person capable of holding the confederation together. As its leader she demonstrated her ability to take command by issuing orders, planning military campaigns, and proving that there were profits to be made in piracy. When the time came to dismantle the confederation, it was her negotiating skills above all that allowed her followers to cross the bridge from outlawry to officialdom.”

We know slightly more about some of the women warriors involved in sectarian revolts. Folk stories passed down orally are one of the sources. Tales that proliferated in northern Sichuan on the battle exploits of cult rebels of the White Lotus Religion uprising in Sichuan, Hunan, and Shaanxi beginning in the late eighteenth century glorify several women warriors. The tall and beautiful Big Feet Lan (Lan Dazhu 籃大足) and the smart and skillful Big Feet Xie (Xie Dazhu 謝大足) vanquished a stockade together; the young and attractive Woman He 何氏 could kill within a hundred feet by throwing daggers from horseback. The absence of bound feet in Big Feet Lan and Big Feet Xie suggests their backgrounds were either very poor, unconventional, or non-Han.

Sectarian groups accepted female membership readily, and many of these women trained in the martial arts. Qiu Ersao 邱二嫂†(ca. 1822–53), leader of a Heaven and Earth Society (Tiandihui 天地會) uprising in Guangxi, joined the sect because of poverty and perfected herself in the martial arts. Some women came to the sects with skills. Su Sanniang 蘇三娘, rebel leader of another sect of the Heaven and Earth Society, was the daughter of a martial arts instructor. Such sectarian rebel bands are frequently regarded as bandit groups. A history of the Taiping Revolutionary Movement refers to these two cult leaders as female bandit chiefs before they joined the Taipings.

Male leaders of religious rebellions frequently married women from families skilled in acrobatic, martial, and magic arts. These women tended to be both beautiful and charismatic. Wang Lun 王倫, who rebelled in 1774 in Shandong, had an “adopted daughter in name, mistress in fact,” by the name of Wu Sanniang 烏三娘 who was one of Wang’s most powerful warriors. Originally an itinerant performer highly skilled in boxing, tightrope walking, and acrobatics, she terrified the enemy with spellbinding magic. She brought a dozen associates from her old life to the sect, and they all became fearsome warriors known as “female immortals” (xiannü 仙女); three of them, including Wu Sanniang, lived with Wang Lun as “adopted wives” (ifu 義婦). A tall, white-haired woman at least sixty years old, possibly the mother of one of these acrobat-turned women warriors, wielded one sword with ease and two almost as effortlessly. Dressed in yellow astride a horse, hair loose and flying, she was feared as much for her sorcery as for her military skills. Her presence indicates that some of the women came from female-dominated itinerant performing families. Woman Zhang 張氏and Woman Zhao 趙氏, wives of Lin Zhe 林哲, another leader of the cult, were also known for being able to brandish a pair of broadswords on horseback.

Hong Xuanjiao 洪宣嬌†(mid nineteenth century), also known as Queen Xiao (xiaohou 蕭后), wife of the West King of the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom (taiping tianguo 太平天國), was so stunningly beautiful and impressive in swordsmanship that she mesmerized the entire army during battles. The link between early immortality beliefs and shamanism also suggests that these women warrior “immortals” of sectarian cults may represent surviving relics of the female shamans who occupied high positions during high antiquity.

During the White Lotus Religion rebellion in Sichuan, Hunan, and Shaanxi beginning in 1796, five of the generals were at once leaders and wives of other leaders of the cult. They were Woman Qi née Wang (Qiwangshi 齊王氏; Wang Cong’er 王聰兒), Woman Zhang née Wang (Zhangwangshi 張王氏), Woman Xu née Li (Xulishi 徐李氏), Woman Fan née Zhang (Fanzhangshi 范張氏), and Woman Wang 王†née Li 李 (Wanglishi 王李氏). In the Heavenly Principle Religion (tianlijiao 天理教) rebellion that began in Beijing during 1713, the wife of its leader, Li Wencheng 李文成, led three invasions into the city. There was even a “Female Army” (niangzijun 娘子軍) within the Eight Trigrams (baguajiao 八卦教) uprising in Shandong during the Daoguang 道光† reign (1821–51). The female generals, Cheng Sijie 程四姐†and Yang Wujie 楊五姐, were particularly impressive when they wove among enemy forces in the style of “butterflies flitting among flowers,” wielding broadswords on horseback, their hairpins glittering in the light.

A number of female rebel leaders used religion and magic to buttress their power. Many claimed to be celestials and were leaders of sectarian cults (...). Chen Shuozhen 陳碩貞†(?–653) mobilized a peasants’ uprising by declaring that she had ascended to heaven and become an immortal. Tang Sai’er (ca.1403–20), a head of the White Lotus Religion (bailianjiao 白蓮教), designated herself as a “Buddhist Mother” (fuomu 佛母). The spellbinding old woman warrior in Wang Lun’s Clear Water Religion (qingshuijiao 清水教) sect was known to the rebel community as a reincarnation of the highest White Lotus deity, the Eternal Venerable Mother (wusheng laomu 無生老母). Wang Lun relied on her for performing magic and the rituals for calling on their supreme deity. Woman Wang née Liu (wangliushi 王劉氏), one of the numerous female leaders of the White Lotus Religion revolt, also titled herself the Eternal Venerable Mother. Wang Cong’er (1777–98), originally an itinerant entertainer, became the commander in chief of the rebel army she launched with her husband, a master in the White Lotus Religion.

Indeed, itinerant performers such as Wu Sanniang mentioned above were frequently trained in the martial arts since childhood and must have been skilled at performing magic tricks as well. Lin Hei’er 林黑兒†(?–1900), leader of Red Lanterns (hongdengzhao 紅燈照), the young women’s branch of the Boxer’s Movement (yihetuan 義和團), was also originally an itinerant entertainer (her husband was a boatman). Designating herself the Holy Mother of the Yellow Lotus (huanglian shengmu 黃蓮聖母), she taught her followers the skills of wielding swords and waving fans as well as magic to defeat their enemies. Wang Nangxian 王囊仙†(literally, Goddess Nang, 1778–97), an ethnic minority of the Miao tribe, was worshipped as a goddess by her tribesmen before she led them in revolt against the Chinese government."

Chinese shadow theatre: history, popular religion, and women warriors, Fan Pen Li Chen

#history#women in history#women warriors#warriors#warrior women#china#chinese history#asian history#historyblr#qing dynasty#19 century#18th century#Wang Cong’er#hong xuanjiao#su sanniang#qiu ersao#tang sai'er#asia#Zheng Yi Sao

177 notes

·

View notes

Text

Viking historian Nancy Marie Brown’s new book, The Real Valkyrie: The Hidden History of Viking Warrior Women, explores what life might have been like for the warrior woman of Bj 581. Using more evidence from the recent tests conducted on the remains, Brown traces her journey from Norway to the British Isles to Kiev then, finally, to Birka. Brown imagines the unnamed warrior meeting other prominent Viking women, such as Gunnhild, Mother of Kings, or Queen Olga, ruler of the Rus Vikings in Kiev. She also explores the Viking sagas and contemporary sources with a new lens.

Atlas Obscura spoke with Brown about her new book, valkyries, and the assumptions that underlie the history we think we know.

How did you initially get interested in Vikings—and female Vikings in particular?

When I went to college, I actually wanted to study fantasy writing and, you know, learn to write like Tolkien. I learned very quickly that that was not appropriate for an English major in the 1970s, so I decided to study what Tolkien studied, and he was a professor at Oxford University, teaching Old English and Old Norse. So I started reading all of the Icelandic sagas that I could find in translation. And when I ran out of the English versions, I learned Old Norse so that I could read the rest of them.

One of the things I liked about [the sagas] the most was that they had really interesting women characters. There’s a queen in Norway who appears in about 11 sagas, Queen Gunnhild, Mother of Kings. She led armies. She devised war strategy. And then I was looking at the valkyries and the shieldmaids and thinking, you know, these are really interesting people that have always been considered to be mythological.

So when I learned in 2017 that one of the most famous Viking warrior burials turned out to be the burial of a woman, that just absolutely dazzled my imagination.

Is this the first confirmed grave of a female warrior that we have?

This is the one that has the best proof. There are one or two others that have since been DNA tested and proven to be female. But in each of these cases, it’s hard to say if the person in the grave, whether male or female, actually was a warrior, or if the object that we are interpreting as a weapon was used for hunting or for some other purpose.

What do we know about the life of the Viking warrior woman in Bj 581?

In 2017, by testing her bones and her teeth, [scholars] could say she was between 30 and 40 years old when she died. They could also tell that she ate well all of her life. So she came from a rich family or maybe even a royal one. She was also quite tall, about 5’7”. By the minerals in her inner teeth, [scholars can determine] she may have come from southern Sweden or Norway, and also that she went west maybe as far as the British Isles before her molars finished forming. She didn’t arrive in Birka until she was 16.

We also have her weapons and a little bit of clothing that were found in the grave. And these link her to what is known as the Vikings’ East Way, which was the trade route from Sweden to the Silk Road.

We can link, through the artifacts and through the bones, that she could have traveled from as far west as Dublin to as far east as at least Kiev in the 30 to 40 years of her life.

How do we know that there were Viking warrior women?

They are mentioned many, many, many times in the literature. In most cases, they have been dismissed as mythological because, of course, we know warriors were men. But we don’t know that. That is an assumption that is based on traditional Victorian ideas that because women are mothers, they’re nurturing, they’re peacemakers, and they don’t fight.

That’s not historically true. Women have always fought. And they appear in most cultures until the 1800s, when Viking studies and archaeology pretty much started. So we sort of have this problem of bias in our earliest textbooks.

There’s this assumption that the warrior men of myth must have been based on real people, but it’s not the same for the mythical warrior women. Why is that?

It’s just an assumption based on what people think women are like. Most of the material we have from the Middle Ages was written by men, and most of the material we have until the 1950s was written by men, and women are slowly making their way into the field of Viking scholarship. But many of them are still working under the assumptions that they were taught.

I noticed when I went back and reread some of the sagas in Icelandic that there wasn’t this clear distinction between the warrior women being mythological and the warrior men being human. When you actually look at the old Norse text, there’s a lot of words that have been translated as “men” that actually mean “people,” but it’s always been translated as “men” because it’s a warrior situation.

Is it possible for historians to remove all of those biases?

No, I don’t think it is. I think we all are looking through our own lenses. But we have to revisit those sources every generation to see past biases. So when you have layer after layer after layer of removing biases, you may get closer to the truth.

What most surprised you in the course of researching your book?

One of the controversies right now in Viking studies is should we really be talking about men and women at all? Maybe there were all kinds of different genders. We don’t know if there were more than two genders in the Viking age. Maybe it was a spectrum.

If you look at this one group of sagas called the Sagas of Ancient Times that are often overlooked because they have all these fabulous creatures in them, like dragons and warrior women. It’s really interesting [because] these girls grow up wanting to be warriors. They’re constantly disobeying and trying to run off and join Viking bands. But when they do run off and join the Viking band, or, in another case, become the king of a town, they insist on being called by a male name and use male pronouns.

So it was very shocking to me to go back and read it in the original and say, “Wow, all this richness was lost in the translation.”

#Nancy Marie Brown#vikings#history#women in history#archaeology#women warriors#warfare#warrior women#norse history#atlas obscura

362 notes

·

View notes

Text

Women Warriors

88 notes

·

View notes

Text

The heroic lady workers of World War II.

This image is from 1943...

114 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book Review 51 – Women Warriors: An Unexpected History by Pamela Toler

This was a book I never would have heard of were it not for the magic of word of mouth marketing (here meaning ‘ recommended on tumblr.com), so I went in with basically no expectations. It’s a history book, but very much pop history – this is a collection of fun anecdotes for a general audiance wrapped in a persuasive essay, not any sort of academic work. Which is to say it’s also extremely accessibly written and easy to read, excellent for when a hurricane hit and you lost power for the day and have nothing to do but laze.

The book is, well, what it says on the tin – a collection of historical woman warriors from across the globe (if disproportionately but not mostly European) from classical Scythian warrior-aristocrats through to Soviet tank drivers (Well, I presume there’s someone out there for whom the ‘unexpected’ bit is still true, anyway. But it’s about women warriors!) The book begins with an introduction that lays out its thesis – that woman fighting in war is thoroughly historical unremarkable, and not any sort of freak aberration or insignificant exception to war being a uniformly masculine affair – and the agenda its trying to advance – that woman should be allowed to serve in the US military on equal terms with men – with I’ll say admirable clarity. Each following chapter is then dedicated to a specific typology of historical woman warriors (e.g. who become warriors due to their fathers, their husbands, patriotic fervour, those who disguised themselves as men to fight), generally consisting of a light coating of theory before diving into the examples and case studies that make up the meat of the book.

I, needing no convincing of the thesis and having limited interest in the politics of who gets to go kill in uniform for America, was reading this entirely for those anecdotes. Those were entirely worth the price of admission – Toler specifies in the introduction that she’s only talking about woman warriors, as in those who either personally fought or directed troops like a man with an analagous command would have, with the result that e.g. Elizabeth 1 gets skipped and some figures I’d genuinely never heard of get included. There’s also something of an attempt to focus on woman who served openly, rather than those who disguised themselves as men, though that’s hardly universal (there’s still at least a couple crossdressing 18th century bravos, don’t worry. Though shockingly enough no Julie d'Aubigny). Each woman profiled gets a short potted biography: her origins, the sources for her exploits and the historiography around her, then a recounting of her exploits, and a short epilogue of her life afterward if there was one (these are rarely particularly happy).

The book’s very much written for the general audience, with some effects on the choices of women to feature I’d call regrettable (e.g. Katherine of Aragon is very clearly only there because people already know her as Henry VIII’s first wife, the historical Mulan probably gets more wordcount than was strictly needed), but overall they were fun and interesting stories, and (thankfully) focused more on explaining why the women profiled were interesting or notable than getting twisted in knots trying to explain why a given mercenary captain or feudal magnate or pirate queen was actually a moral role model or feminist icon or something (an issue a lot of works in this vein do fall into, I’ve found).

I do wish there was more of an attempt to theorize about the general role of religion, given (if nothing else) the sheer wordcount Joan of Arc gets. But overall? No complaints, plenty of fun interesting historical figures I’d never heard of before.

The author does have a couple very clear pet peeves that each get called out often enough I felt like I should start a drinking game. These range from the entirely sympathetic (yelling at how previous generations of historians have applied wildly different amount of skepticism when reading sources about male versus female warriors) to very fair points that are probably a bit belaboured (by orders of magnitude more woman have fought openly as woman in e.g. sieges of their homes than ever disguised themselves as men to join the army) to the sort of thing that only really makes sense as a pet peeve when you remember Toler spent like a decade reading the source material for this and got pretty sick of the tropes (her visceral annoyance whenever anyone is refereed to as ‘th Joan of Arc of [X]”).

Speaking of pet peeves – Toler keeps a very casual, conversational sort of tone throughout the book, full of asides and tangents. She’s got a very strong voice, and it’s just a matter of taste whether that’s a positive or negative, I suppose. She also uses a lot of footnotes for her asides, especially about historiography and sources, and very annoyingly just uses a basically random series of symbols that I couldn’t distinguish half the time to mark them instead of just using numbers. The combination can grate on occasion, though that might just have been my eyes getting sore reading all the small text.

Politically the book is very consciously and explicitly liberal feminist propaganda, in a way that feels oddly dated for something that came out in 2019? Also incredibly American (woman across the globe are profiled, but she clearly assumes a lot of prior familiarity with, like, the folktale of some woman who loaded a canon during the American Revolution once, and similar). Toler is, as mentioned, incredibly passionate about the cause of women’s service in the united states military, something which I haven’t seen mentioned in the news for so long it almost seems quaint (even though I have no idea whether anything’s like, changed.) Honestly given my social circles at this point it was mostly just deeply bemusing to read a book by someone who clearly considered ‘being able to serve in the US military’ as, like, something to fight for and take pride in. But even beyond that, a lot of the avuncularly and style just felt very 2010s online feminist, I suppose? I really would have assumed the book came out in 2014 or so if I hadn’t checked.

Speaking of – it was just deeply strange how the book had no framework to discuss trans-ness? As in, several of the people the book catalogues disguised themselves and joined the army as men and even after being found out just, never stopped. To the point of fighting duels over the matter, sometimes! And the book never figures out a graceful way to handle referring to them (the ‘him’, scarequotes included, makes a few appearances), let alone really discuss identity. Again, makes the whole thing feel like a bit of a time capsule – it’s about the handling of the issue I’d expect from, like, an old Cracked listickle about ‘10 badass women warriors you’ve never heard of!’, not a recent book clearly marketed towards a progressive audience.

Anyway, as a work of theory or historical scholarship, not going to set the world on fire. But did teach me about the times the Pope and Emperor of Russia separately gave people written permission to crossdress and stab people, and also an actual written pocket biography of Matilda of Tuscany I can cite instead of just ‘forum threads arguing about Crusader Kings 2 circle 2013”. So on balance not a bad read. Just don't go in expecting theory or political enlightenment.

67 notes

·

View notes

Video

Life Finds a Way .....

Even in war!

#ukraine#russia#russian war on ukraine#cat#kitten#pets#pet life#pet lovers#sweet#cute#adorable#peace#peace for all#peace for ukraine#women warriors#women soldiers#life finds a way

346 notes

·

View notes

Text

"For decades archaeologists have puzzled over whether the stone-lined burial chamber, which was discovered in 1999 on Bryher, contained the remains of a man or a woman.

Excavations revealed a sword in a copper alloy scabbard and a shield alongside the remains of the sole individual, objects commonly associated with men. But a brooch and a bronze mirror, adorned with what appears to be a sun disc motif and usually associated with women, were also found. The grave is unique in iron age western Europe for containing both mirror and sword.

Now a scientific study led by Historic England has determined the remains are that of a woman, a discovery that could shed light on the role of female warriors during a period in which violence between communities is thought to have been a fact of life."

(...)

“Although we can never know completely about the symbolism of objects found in graves, the combination of a sword and a mirror suggests this woman had high status within her community and may have played a commanding role in local warfare, organising or leading raids on rival groups.”

Stark added: “This could suggest that female involvement in raiding and other types of violence was more common in iron age society than we’ve previously thought, and it could have laid the foundations from which leaders like Boudicca would later emerge.”"

49 notes

·

View notes