#wonder rondo

Text

mika.........................................................

#ohhhhh in love w this one#i was wondering how theyre gonna top kohaku to ruri no rondo but this is. majestic#duck rants about something

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

At this point I would’ve preferred them keeping the damsel in distress plot point for Annette. Because. Wdym she was a slave and is now a metalbender. Who the hell are you talking about.

#yeah Maria and richter get to be mostly game accurate but Annette gets replaced by a random character that shares the same name as her#besides the whole ‘don’t call this shit a rondo of blood adaptations if you’re just going to change everything’ where the fuck is Dracula??#yknow the guy they’re supposed to be fighting against. the set up for symphony of the night. that guy.#only slightly relevant to this post but black women never get to be the ones getting saved#oh boy I wonder why that happens (racism)#the other race changes were strange as well#me watching these two fine ass dark skin vampire serve that fuck ass bitch erzebeth 😐#never played bloodlines but I’m sorry Elizabeth but they made you ugly☹️#the fact the made Annette really aggressive too… read the wiki and what the fuck do you mean she makes fun of richter for running away for#*from* THE VAMPIRE THAT KILLED HIS MOM IN FRONT OF HIM#castlevania#castlevania anime#netflixvania tw#tired of things having to be time period accurate… couldn’t we just had a cute nice romance between a black woman and her himbo boyfriend#and Maria is there too I guess#although it’s always been her role in the story to just. be there

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’m bringing this back, Kiyozuka’s arrangement of Rondo is just so good

Full video here .

The connection of Yuzu with this piece’s notes is just otherworldly, I can’t WAIT to see it redeemed like this.

27th cannot come sooner

#yuzuru hanyu#figure skating#I wonder who is going to perform with yuzu#i’m betting on a pianist#some wish a violin#what if it is kiyozuka himself???#i’m going to cry#aww translation#rondo#fs program insight

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

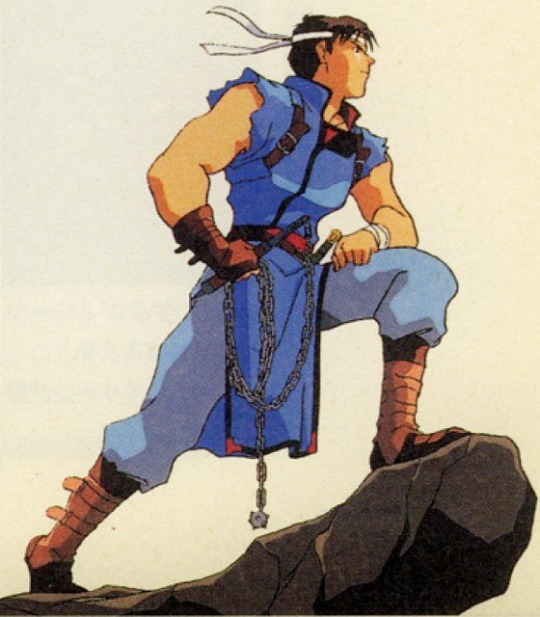

Looking at Richter makes me understand some parents' feelings about their kids...

I see this man

Or this man

And I'm not like "Ah, yes, he's gonna be a dad someday"

I'm more like... "This boy's gonna stay a baby till the day he dies" JUST LOOK AT HIM- HE'S PRECIOUS. PRECIOUS LITTLE ANIME BOY-

Even this design.

Wich makes him look more mature and tidy... I just can't picture him having a damn KID. LIKE. HIS OWN KID. NO WAY. NOT HIM. I MEAN- I'M SURE HE WOULD BE A GOOD DAD BUT- BUT HE- HE BABY ??

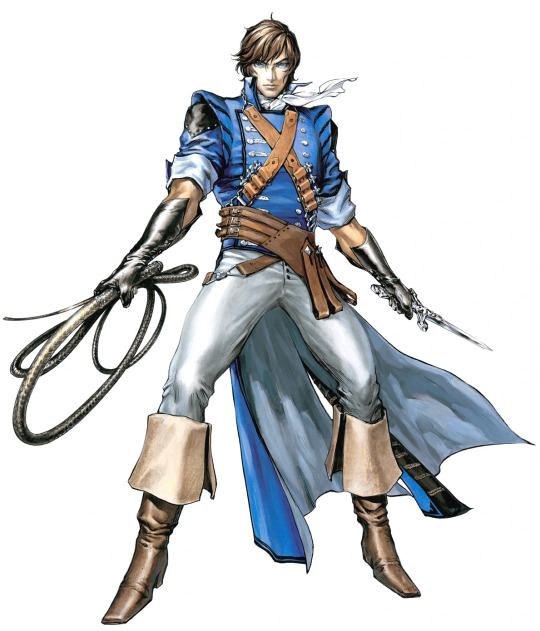

And this design...

IMO it's the most "daddy" of them all. But he's still Richter...

This long hair and prestigious aura... The stand... The facial expression... all of this is just a FACADE. Deep down he's still this wild but righteous BOY !!

No other Belmont have this "absolute baby. must protect." vibe... And he's THE (second) STRONGEST OF THEM !! CAN YOU IMAGINE BEING SO POWERFUL AND STILL EVERYONE SEES YOU JUST AS A BABY THAT MUST BE CARED FOR ?? IT'S VERY FUNNY BUT NOT FOR YOU.

He's not even my fav but i'm still obsessed. All of the other Belmont i can see as fathers, but Richter... Richter's the only one i can't even imagine growing up :( And i'm looking at him BEING a grown up, like oeirhgmserlngmsrelkngmrenkg I WOULD BE A VERY ANNOYING PARENT TO HIM.

#i wonder if Juste felt the same way........... yeah definitely#Richter is everyone's kid in the family#i can't believe he's JULIUS' ancestor... i can't believe he's AN ANCESTOR AT ALL#LIKE WHAT THE HELL#he had sex ?? with a WOMAN ??#and a BABY popped out of her ?? AND HE TOOK CARE OF IT LIKE AN ADULT ??#LITERALLY CANNOT BELIEVE IT#castlevania#richter belmont#rondo of blood#dracula x chronicles#symphony of the night#grimoire of souls

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

d4′s been doing a ton of collabs lately on jp and honestly i don’t blame them

#itlogthoughts#if i;d have to come up with a new story each week my creative juices would be drained right out of my body fr#hell i know there;s potential (esp with the newer units) but it;s still giving me a headache imo#it;s still insane to me that abysm is basically stuck in japan for now for probably a few years until their contract with sho ends#(unless he breaks it off early but knowing him he probably won;t)#i wonder if we;ll get another d4fes? it;s not unlikely since it would be an option to mix up the units again#the main problem with that though is we still haven;t gotten stories for 2 of the old shuffle units#plus it may not be necessary since. well it seems students of other schools can just hop on into yoba whenever there;s a music fes#so Ri4 M4 and RONDO are all covered lol#personally i haven;t found a pattern to guessing the d4 writers (and any time i;ve guessed i was. wrong LMFAO) so it;s a shot in the dark:#that we;ll probably get a story from one shuffle unit out of the blue#and more of the recent stories will focus on the new units#i still wonder about CoA and we still don;t have shano;s card here on eng for whatever reason#so idk anymore we;ll see what happens#hiiro is still a mystery to me though and i really like whatever she has going on with nagisa#so a nagi/hiiro relations event would be pretty cute ngl (highly unlikely)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

i feel like the fact that most of the books i read as a kid were by australian authors has really limited my experiences and relatability to the masses. the only emily rodda property that i can imagine a large amount of people knowing is deltora quest because it got an anime adaptation jhsvjd

#.txt#i NEED to find my copies of the rondo trilogy books… genuinely only know where like the second one is#i went to book week one year dressed as rowan from rowan of rin#some asshole on the bus called me robin hood for like a year tho because the costume included a hat#that was NOT in the books btw but my mum made me wear it anyway#just because it came with the costume#and she could pin my hair under it to make it look short#i wonder if the fact that i insisted on dressing as a boy was foreshadowing for anything

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

All of the sudden it is 90° and I remember that later in the year it'll get to be up to 110° (maybe)(☹️☹️☹️☹️☹️☹️☹️)(please god no) and I think. The world is too vast, too expansive, for one little person (me) to be So Goddamn Hot

#havent even been outside for 5 min....#uuuurgh#i dont wanna go outsiiiide not ever again.....#if i could just sleep until my birthday#thatd be pog i think#a nice cool nap where i dont everheat or get uncomfortable#and my game dailies get done by themselves wwwww#and my aoi grind succeeds#ahhh.... the new groovyfes rondo cards....#i wonder what nagisas will be....

0 notes

Text

aaaaaahhhhhhh i finished like. thirty-two chapters or whatever of the first d4fes story, the final bits of lyrical lily's first unit story or whatever it was called, and my draft for yuka's b-day.

wahoooooooooooooo

#crow talks#d4dj#weeeeeeeeeugh#ibuki and dalia have terrible communication skills pls help them.#surprised noa managed to keep her cutie urges under wraps until the very end lol#rondo showing lyrical lily around and letting them see different units and their worldview was cute!#quite interesting to see!#them explaining and giving some sort of advice to them was so sweet like. that's their older sisters kinda!#wonder what's going on w calendula#all i know is that it's cursed and stuff but idk what will its effects be#also wonder why haruki thinks michiru's is shit she sounds pretty good from what the others guys were saying...#idk maybe i'll find out when shinobu shows up or when im done

1 note

·

View note

Text

Everything happens for a reason part 3 - Alexia putellas x pregnant!reader

Author note- hey guys here’s part 3! Hope you are enjoying the series! Please leave a comment with any feedback (positive or otherwise) it’s always helpful 🤍🤍

Warnings⚠️ swearing (that’s about it I think) it’s mostly angst

————

Part 1- https://www.tumblr.com/apute11as/733631966220582912/everything-happens-for-a-reason-alexia-putellas

Part 2- https://www.tumblr.com/apute11as/735082085825576960/everything-happens-for-a-reason-part-2-alexia

—————

The next day rolled around fairly quickly as you and Alessia had made a brief exit, claiming travel sickness to be the cause of your tearful exit from the room. As you woke up the next day you were met with the sound of a blaring alarm that read 6:30am.

Groaning you began to trudge out of bed, as Alessia did the same from the other bed.

“What are you doing?” Rung Alessia’s sleepy voice.

“Getting ready for training?” you said, puzzled.

“Oh are you sure you want to play, do you feel well?” questioned the striker

“yeah surprisingly I feel alright this morning” you smiled but you were soon cut off by a harsh ringing of your phone and were met with Alexia’s face plastered across your screen. You hesitated at first but then clicked the green button.

“Bon dia mi amor, I was starting to this you weren’t awake” came the a husky, Catalonian voice.

“Hey baby yeah I’m up sorry just misplaced my phone.” you assured her.

“How is camp are you feeling better now?” she asked, her voice laced with concern.

You hesitated for a moment, wondering if maybe you should just share your concerns with your wife, knowing that she could potentially offer clarity. However you ultimately decided against it as you had your mind set on attending the World Cup and playing as much as possible. Your mind wandered as you began working it out in your head, realising that by the end of the tournament, you’d be almost 3 months pregnant which would likely carry risks when you played.

“Princesa? Are you still there?” your wife questioned with worry.

“Lo siento Ale I’m here, I’m just so tired sorry my mind isn’t focusing.” you offered

“I understand bebita, I’ll call you back later vale?” the Spaniard inquired.

“Sí of course I’ll call you after training, te quiero mucho Alexia.” you voiced

“I love you too amor.” she replied blowing a kiss at the screen, which you returned before ending the call.

“You ok?” Asked Alessia with a pitiful smile.

“Yeah I’m good. Thank you Less I really mean it.” you replied

“always and we’ll get the test later to calm your mind down” she smiled

———

The morning had been relatively smooth, with minimal nausea and training with the girls had even distracted you completely for a number of hours- something that you welcomed with open arms. During the rondo is when it all started to take a turn for the worse. You felt yourself growing more easily tired than usual, struggling to catch your breath after a run down the wing, the sick feeling started to form.

You’d been stood in a small huddle half way through the drill when you felt the bile begin to rise in your throat and before you knew it you were making a run to the changing rooms and throwing up in the nearest bin. Alessia and Mary were close behind and you felt a hand rubbing up your back as you dry heaved into the bin.

“come on y/n we’re going to get the medicine” said Alessia

“what medicine?” you questioned, whilst attempting to regain your composure.

“You know what we talked about getting at lunch? To cure your illness” she said through gritted teeth as your mind finally caught up.

“Ohh ok yes sorry” you replied, eyes darting between her and Mary.

“What’s up with you?” Asked Mary, concerned.

“Just the flu we think” you answered, stoically.

“Should you be playing??” She urged

“Probably not but I didn’t want to worry anyone” you lied about your condition

“Y/N your health should come first always!” Mary insisted.

“Sorry Mar it will next time I promise” you offered, which seemed to be enough for you as she allowed you and Alessia to leave, whilst she told the team of your suspected flu- an answer they gave little question to.

———

The journey to the shop was brief. You slipped in with hoods up and made sure to use self checkout to minimise the risk of being spotted because what a scandal that would cause.

Once you returned to your shared room, the two of you made your way to the bathroom, carrying three different brands of pregnancy test in your bag.

“Do you want to do them all at once?” Alessia inquired.

“I mean I doubt I have the pee control to do it any other way” you replied, attempting to lighten the tense mood.

You sat down on the toilet and held the tests below you as Alessia turned to face the door. Once you’d taken them, you turned all three face down on the counter and the two of you sat on the stone floor of the bathroom with a 5 minute timer on Alessia’s phone. Your mind wandered to your wife in Spain as the guilt crept in about keeping this potentially life changing moment from her.

Before you could get too absorbed in your thoughts, the timer sounded signifying it was time to check the tests.

“you’ve got this.” Reassured the blonde with a small smile.

“3, 2, 1” you rehearsed before flipping the text.

First one: positive

Second one: positive

Third one: positive

“Oh shit” Alessia voiced.

“Oh shit indeed.”

“What are you gonna do? Shall I get your phone I can leave whilst you call alexia?” Said the striker.

“No. She can’t know.” You responded emotionlessly.

“What why not?” Alessia questioned, shock evident in her tone.

“She’ll stop me from playing Alessia. I have to play! By the time it’s noticeable the World Cup will be done and I’ll tell her then to cheer her up if neither of us win it or to add fuel to the celebration if one of us does. Oh my god what if she’s not happy?” your breathing picks up rapidly “she wanted the baby before but what if she’s changed her mind Alessia?” Your breathing was becoming frantic.

“Calm down y/n/n breathe just breathe” Alessia said putting a comforting hand on your shoulder.

“I can’t Alessia! What if she leaves me? I can’t raise a baby on my own!” You began to hyperventilate, reaching a state of full blown panic.

“Y/n you need to breathe ok, we can sort all that after, you don’t need to tell alexia today just calm down, breathe, think of the baby ok, breathe for the baby!” Alessia urged.

“Ok ok” you said steadying your breath, Alessia’s grip on your shoulders grounding you.

“You feeling calmer now?” questioned the blonde.

“Yes thank you Alessia it really means a lot” you smiled, hugging the younger girl.

——

The first game of the tournament came around fast. With it being Haiti, you weren’t too concerned as they hadn’t been an especially tough team in the past. You still hadn’t told Alexia about the pregnancy. Although Alessia had managed to convince you to see a doctor, luckily she wasn’t a football fan so had no idea who the two of you were, and much to your amusement she confused you as a couple which sent the two of you into fits of giggles, before correcting her. You and Alexia still kept in contact, she’d noticed something off with you but each time she’d brought it up, you shut her down with and blamed it on fatigue. She wasn’t stupid and didn’t buy a word of it but she also knew you’d tell her in your own time, whatever it was so she didn’t push.

When sarina announced you to be in the starting eleven you sighed heavily, realising that the game would be tougher than anticipated. What’s more, you were playing centre back. Normally, you played CDM or on occasion CM but with Leah out and Millie having picked up a light injury in training, England were short on reliable centre backs.

As the whistle sounded to signify the start of the match, you drew a sharp breath in anticipation of the difficulty these next 90 minutes would prevail.

—

Half time came around eventually. After a gruelling first half, you welcomed the break. You were leading 1-0 only thanks to a penalty from Georgia, which wasn’t overly comforting as Haiti were putting up a fair fight. You were forced to make some risky tackles, many of which ended up with you on the floor, body twisted at awkward angles. This did nothing to help Alessia’s growing anxiety for you. She’d become protective over you as she felt partially responsible, being the only one who knew about the pregnancy still. Every time you’d gone down with a challenge, she’d been by your side, checking you over (despite being practically on opposite ends of the pitch).

What you didn’t know was that Alexia was sat in a hotel room, watching every interaction and was beginning to grow suspicious of your new found closeness to the blonde striker. Lingering touches which to you and Alessia were nothing more than her checking on you and the baby, to Alexia were symbols of a growing affection between the two of you. Her jaw remained clenched at every interaction.

——

The game ended 1-0. A tight win but the three points were yours nonetheless. Your body ached all over. As you headed for the coach in a slumped motion due to the fatigue, you were stopped with a warm hand on your shoulder, one that belonged to Lucy Bronze.

“Hey Luce are you ok?” you sighed out.

“I’m alright Mrs putellas but are you?” She asked with concern. You cringed at the nickname she gave you before responding.

“Tough match that’s all, why do you ask?” you inquired with a furrowed brow.

“Alexia told me you weren’t yourself lately, asked me to check up on you. Oh and also I was quite concerned to hear that you didn’t tell her about your quite awful round of the flu the other week?” she questioned

“Oh erm must of slipped my mind?” You offered weakly.

“Yeah I’m sure, what’s really up Y/N?” Questioned the brunette.

“I-I can’t tell you” you stuttered, eyes damp with tears that threatened to fall at any moment.

“Why not, you know you can trust me with anything?” she said, face contorted with a mixture of confusion and hurt.

“I know Lucy and I love you for it but it’s personal I’m sorry.” you half smiled at her

“Yeah yeah I get that, you don’t have to tell me but you should really tell your wife.” She rebounded.

“No she can’t know!” You said on reflex, as though you were talking about it to Alessia.

“Know what? Y/N I’m worried now what’s going on?” Lucy pushed further.

“Y/N” called Alessia, jogging towards the two of you. “Are you coming?” She gestured to the bus.

“Yeah of course.” You smiled at the striker. Lucy however, didn’t miss the relaxation of your body at Alessia’s presence. Making a mental note to bring this up when Alexia called again.

——

Alexia’s POV

Y/N has been off with me for weeks. Ever since that day she left for the World Cup, she’s been so distant. At first I thought it was to do with us being rivals at the World Cup but now I fear there’s something more.

After watching her game against Haiti, I noticed her closeness with Russo, England’s young striker. My stomach twisted in discomfort as I watched them interact, Y/N responding to her touch in the way she’d normally only do for me. Jealousy rippled through me, could it be? Is this why she’s been off with me? Was my wife really cheating on me with her teammate?

Back to neural POV

Frantically, Alexia called Lucy for the second time this week. After a few rings she picked up.

“Hola Capi” sounded the English- twinged Spanish of Lucy bronze.

“Hola Lucia, well done on the game”

“Gracias Alexia? Not to be rude but why are you calling me?” She questioned

“Has Y/N been acting weird at all?” She asked simply

“Funny you say that she was being odd earlier. She seemed sad so I asked her what was up and I got minimal response but then I got her to crack a little. She told me there was something but she couldn’t tell me. Then Alessia came along and grabbed her to go to the bus. They spent the whole journey whispering about something so I’m not sure what to take from it?” Offered Lucy

“That little bitch” snapped alexia

“Woah what now?” Questioned Lucy at the harsh words Alexia had just produced

“I think she’s cheating on me Luce” replied alexia, both anger and sadness laced her voice.

“Oh wow Ale that’s a huge conculsion to jump to.” Stated the older woman.

“Well did you not see how much they touched eachother in that game. I was observing them the whole time Alessia was practically glued to her at every opportunity.” Snarled alexia.

“Now that you say it they’ve been spending a lot of time together but I wouldn’t make any rash decisions on the matter Alexia.” Offered Lucy.

“Thanks Lucy I’m gonna call her now.” Alexia stated harshly

——

After the team bus made its way back to the hotel in Sydney, you and Alessia wandered up to your rooms (next door to eachother as requested). You’d barely been back and hour before you received a FaceTime from your wife. Weird, you’d thought. It was a couple of hours earlier than you’d discussed but you brushed it off and answered anyways.

“Hola mi amor” you spoke down the phone.

“Fuck you” came your wife’s angry tone

“W-what? Mi Vida are you ok?” You asked with concern in your voice

“You’re cheating on me are you, with Russo?” She snarled

“WHAT?! No Alexia where did you get that from?” you were shocked at this revelation

“I saw the two of you in that game, every time you were tackled she was right beside you. She’s up front you’re a defender for fucks sake you’re miles away from each other!” She practically yelled down the phone.

“Alexia no it’s not like that at all, she’s just been looking out for me.” You reassured the Spaniard.

“Looking out for you? I know we’re not seeing eachother for a while but i didn’t realise you were pathetic enough to need another woman to satisfy you! It’s been 3 fucking weeks Y/N!” She roared

“You don’t understand Alexia I needed someone to talk to, to support me in person.” you were in tears now.

“SUPPORT YOU? What the fuck with? I call you everyday to check in and you won’t tell me anything so you’re whoring yourself out to the next person you can find!” She pushed further

“No Alexia! It’s not like that not at all please!” You begged

“Then what is it huh? What could you possibly need support with that I can’t give you right now?!” She boomed

“Alexia, I’m- I’m pregnant! The IVF worked its your baby, sorry you had to find out like this.” you burst into tears.

Alexia sat there in shock. You were pregnant, with her baby, how could she have been so stupid!

—————

#woso#woso imagine#woso x reader#espwnt#fcb femeni#espwnt x reader#fcb femeni x reader#alessia russo#alexia putellas x reader#lionesses#alessia russo x reader#alexia putellas imagine#alexia putellas

621 notes

·

View notes

Text

Aw I really enjoyed that event story:) I know Tsubaki and Nagisa kind of butt heads often because of their conflicting personalities so It’s nice to see them work through some of that and learn to work with each other better and become more friendly with one another. I’d love for them to become closer, I think Nagisa would actually be really good for Tsubaki, I think she’d help her come out of her shell a bit.

#Tsubaki Is not very good at expressing her emotions obviously so It’s wonderful to see her be able to work things out In a healthy manner#And I’m glad that all of RONDO are there for one another. I love them so much

0 notes

Text

I was suppose to get this done last month but got really sick so I had to postpone it sadly, but I'm so happy it's finished now!

Drew one of my favorite ships from the askblog, Medley is the GOAT! Happy belated birthday, Nori! Hope your birthday was great and wonderful!

(@harmonia-university/@rondo-grazioso)

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

Just binged Castlevania: Nocturne, and I enjoyed it.

Some people I guess are pissy that Annette is black now, but having never played Rondo of Blood (or got far enough in Dracula X) I don't mind it; this makes her more interesting than the classic damsel in distress she was in the game, plus it means she and Richter get to inherit the Battle Couple mantle from Trevor and Sypha. Also, considering the whole French Revolution setting and themes of liberation, it doesn't strike me as "woke." It'd be another story if previews were like "LOOK AT OUR STRONG INDEPENDENT HEROINE". Things are allowed to be diverse.

Richter overcoming his hangups and getting his magic back, tying that white wrap around his head and that rendition of Divine Bloodlines was just *chef's kiss*

Edouard's story and his history with Annette gave me some good feels. Interesting that Erszebet Bathory is the villain when her appearance in Bloodlines was set during World War I, but Netflixvania has made abundant anachronistic references to the games before, and sometimes you just need a famous folkloric vampire to be the big bad evil guy. I wonder if Richter and the gang will go on a road trip around Europe like John Morris and Eric Lecarde did in Bloodlines?

I can understand why some would feel Maria is annoying regarding her attitude towards the church (considering Blue Fangs in the previous series had a better understanding of God than plenty of people in real life), but her feelings are a bit understandable considering the Abbot actively doesn't help matters by calling revolutionaries "godless" and such. Also, bear in mind: This is the first season and Maria's still a teenager on top of wanting revolution, of course she's going to be acting insufferable. If there are future seasons, she might be forced to recognize the problem is that people are responsible for their actions and use faith to justify it, just as the Abbot has.

Also, hell yes Mizrak the Gay Black Templar Looking Guy, welcome to the team!

Also HELL YES JUSTE BELMONT APPEARANCE (reminding me to finish Harmony of Dissonance) AND ALUCARD'S BACK LET'S GOOOOOOO

119 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sherliam songs

I will list some song I think fit Sherliam. But first, I HAVE EXTREMELY BAD TASTE IN MUSIC. So be prepared.

First, Morimyu Sherliam songs. Nothing can beat this. Everyone should watch Morimyu. It's so perfect. I haven't seen OP 5 yet, my DVD still haven't arrived, but my favorite songs from other OPs are I hope/ I will part 1+2, Kokoro no rondo, In this lonely room, OBVIOUSLY

Waterloo. To put it simply, they are each other's Waterloo. William can't escape from his feelings for Sherlock even if he wanted to. Sherlock met his destiny: William. He promises to love him forever more. Knowing their fate is to be together. blablabla

If only. Yes, it's the song from Descendants. Don't judge me. It's from William's POV. Basically, William is wondering, what are these feelings he feels for Sherlock. Up till now, he walked the line, but now Sherlock came. He can't decide, which way should he go. To let his feelings bloom, or bury them inside. Will Sherlock be with him, after he learns the truth? (Yes, he will)

Rewrite the Stars. Kinda mainstream I think. But fits perfectly. I think the whole lyrics speaks for itself. Just listen to it. In short, they love each other very much, but William thinks that it won't work (because of his plan)

Schody z nebe. It's a czech song (I'm from Czech Republic.) It kinda fits. Some lines translate into english: God knows I want to die by your side.. (We are discovered by the guards). God knows that I walk those stairs from heaven with you holding me close. ... Now it's their (Sherlock an William's) turn, they will stay together, and he (God) will answer their prayer... and more

So, yeah, that's it. It's quite shitty but, who cares XD

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Trying to make sense of Umineko while playing it for the first time, essay post-Ep1: The Beatrice lies in the details

0. On games, interactivity, roulette, and chess, or: how to lose at Umineko

Umineko no Naku Koro ni, commonly translated as Umineko: When they cry, also translated as Umineko: When the seagulls cry, also abbreviated as Umineko, also subtitled (I think?) Rondo of the Witch and Reasoning, is a visual novel series originally released between 2007 and 2010 by the group 07th Expansion, under the influential authorship of Ryukishi07, also abbreviated Ryukishi in fandom discussions. Umineko might best be classified as a story[i]. As far as the medium goes, Umineko has, as far as I understand, existed in form of an online visual novel, a PS3 game, a manga, a downloadable visual novel, and an anime, if not more. And yet, as I experience Umineko, I have paid for it and downloaded it from Steam, as well as having installed a massive and wonderful total conversion mod on top of it. The question of “what is a game” is an esoteric one, one that renders “is Umineko a game” absurdly unanswerable. But while categorizing Umineko as a game or not a game is difficult, it is easy to see that Umineko has a loaded allegorical relationship to game(s).

In Episode 1 of Umineko, Legend of the Golden Witch (to be called Ep1 from now on), two different games are brought to the table regularly, both as metaphors and games characters play: chess and roulette. Chess and roulette are very different games, almost diametrically opposite. Chess is a game in which every move can be calculated, at least in theory. While such computers are yet to be created, a computer with sufficient capacity of calculating could simulate every possible chess game, always know a certain path to victory. Humans are incapable of knowing every single possible chess game at once. Humans playing chess at a high level memorize and execute cyclical patterns and try to guide their opponent(s) into patterns and cycles they are unfamiliar with. Despite having no randomness involved, despite seeming predetermined every time, chess is a fascinating and very human game to play. And, indeed, a lot of the humans (and witches) in Umineko Ep1 play chess. When Ushiromiya Kinzo asks his resident doctor and old friend how long he still has to live in the prelude, the doctor points to a chess game they are playing to establish a metaphor. When trying to solve the death of his parents as a crime, Ushiromiya Battler turns to chess and the repeating idea of “spinning around the chessboard” to find the culprit. Who plays chess against whom and with what level of skill is a motive and allegorical theme repeated over and over and over again in Umineko Ep1.

While no character in Umineko Ep1 plays an actual game of roulette, roulette is also a repeated motive in this story. Roulette is random or not random depending on a complex philosophical debate around determinism – but on a well-designed roulette table, no human or computer is able to tell the outcome of a spin of the wheel. To many minor factors, like air flow, friction of minute surfaces, gravitational pulls, and rotational momentum make roulette highly random. In Umineko Ep1, the so-called demon’s roulette is a repeated motive pertaining to the potentially supernatural violence that characters are subjected to as the deaths and murders commence, as well as an allegory for capitalism. One character in Umineko Ep1, a child servant by the name of Kanon, wants to withdraw from this seemingly randomized violence of the demon’s roulette by explaining that he will become the unforeseen variable in this roulette game, the Zero, neither red nor black on the roulette wheel, and therefore a gamble to bet on. I do not know a lot about roulette, but if I recall correctly, the Zero is part of roulette not as a game-breaking but game-enabling mechanism; through the Zero, the house has a statistical edge on a longer and longer series of roulette games.

Be that is it may, both games are referenced and loaded with meaning in Umineko Ep1. Chess, not random and a clash of human minds, versus roulette, totally random, a game of chance without reason; this opens a spectrum through which to categorize any other game. Some characters as well as some of the menus in Umineko Ep1, particularly Lady Bernkastel in the second-order frame narrative, urge the players/readers/player-readers to treat Umineko as a game of chess, one with pieces, invalid and valid, better and worse moves. This framing of Umineko as a chess-like game implies that Umineko could be solved. The question is what it means to solve Umineko. Umineko happens. It happens to the player-reader. The player-reader cannot change the story on any level of the story. Sure, in the first-order and second-order frame narratives, the player-reader can choose to turn the descriptions of characters in the menu that functions as a dramatis personae to their respective dead or alive states, which reflects what happens when the dramatis personae updates during the happenings of the embedded narrative. But toggling states in the dramatis personae doesn’t change anything; the player-reader but sees different text describing characters. Beatrice’s entry into the dramatis personae in the first-order and second-order frame narratives even taunts the player-reader with their powerlessness, the inability to interact, when you try to set Beatrice’s entry to dead. If Umineko is a game, it is not played within the mechanics of the software. Umineko is, if even playable in the first place, played metatextually. Presenting itself on the outset as a murder mystery, solving Umineko means unravelling its mysteries as it progresses. There is no apparent win-or-lose condition to Umineko.

And yet, one does not simply commit to a story as massive and complex as Umineko without prior knowledge of it. I got into Umineko because of @siphonophorus/Ozaawa’s obsession with it. Ozaawa is a cherished discord friend, who has had Beatrice as their profile picture ever since I can remember. I had started Umineko Ep1 with multiple spoilers in mind, such as: “There is a long time loop”, “Beatrice is really queer”, “people die and get resurrected over and over again”, “magic somehow is and isn’t real at the same time”, and “the narrative structure is a mess”. But the most intriguing piece of knowledge is as follows: “you can solve a lot Umineko from very early on”. Apparently someone in the fandom named pochapal had solved large pieces of the puzzle very very early on in the course of the story. Now, since Umineko urges you to treat it as chess, there is an analogy that immediately sprung to my mind: There are ways to checkmate someone in chess in the least possible amount of moves, a common one of these strategies being called a scholar’s mate. Four moves by the player controlling the white pieces lead, under ideal circumstances, to a checkmate and victory. Without knowing the solution to Umineko, you can meaningfully solve Umineko in a (relatively) short amount of story. I call this idea Umineko’s scholar’s mate. I want to explore this possibility, one of the primary reasons why I am writing this essay and plan on writing more of them in the future; to solve as much as I think I can after every episode. Writing this essay is me playing Umineko (I think). There is however a massive problem to me being obsessed with Umineko’s scholar’s mate; namely, that I suck absolute ass at chess and detective/murder mysteries. I am also rather mediocre at literary analysis, and cannot call myself a literary scholar in a great capacity. Congratulations to pochapal for doing Umineko’s scholar’s mate or at least coming close to that, I will not be able to reproduce that achievement. I have invested roughly 31 hours into Ep1 and I still do not know where to start solving the epitaph or who was killed how by whom. I am a historian, and that is about the range of my expertise. I almost did not write this essay and had been moving into Ep2 for roughly thirty minutes before a dumb joke I made on Discord lead to a lot of pieces clicking into place and me being able to synthesize a stable, if a bit tangential reading of Ep1 (more on that serendipitous accident in section 3 of this essay).

All in all, I am obsessed with this story to an extreme level and my brain is constantly trying to crack its mysteries. I invite you to join me on this journey, a delayed live-commentary of my first play-readthrough of Umineko. That being said, given the nature of my approach to play-reading Umineko, I’d like to avoid spoilers for Episodes I have yet to read as much as possible, and I’d hope anyone reading this will respect that wish.

Content warning: Umineko is a horror story that deals with a lot of systems of violence in gruesome detail. So much violence in fact that I fear the content warning in itself could be triggering. The full content warning will be found under the Read More.

Umineko Ep1 contains in varying degrees of alluding, mentioning, and describing: extreme gore, murder, suicide, sexual assault, patriarchal violence, class violence, child labour, grooming, familial violence, intergenerational violence and intergenerational trauma, child abuse, misogyny, psychological horror, colonialism, imperialism, and fascism.

1. On Umineko Ep1, or: Synopsis

The story of Umineko Ep1 unfolds in stages. The first stage to unlock is the embedded narrative of Ep1. It opens with a prelude on the island of Rokkenjima, a fictional, circular island with a circumference of roughly ten kilometres that is part of the real-life volcanic Izu Archipelago of Japan[ii], a short amount of time before Saturday, the 4th of October 1986. A conversation between Ushiromiya Kinzo, patriarch over the ultrawealthy Ushiromiya family and man who bought himself into the title of “owner of Rokkenjima”, and Doctor Nanjo, his attending physician and long-term friend, unfolds in Kinzo’s study in his mansion. Nanjo reveals to Kinzo that the latter is dying and has not much time left, explaining to Kinzo that he might want to settle his affairs. Kinzo reacts, in the presence of a disturbed Nanjo and the much more calm and collected head servant Genji, with at outburst of anger, revealing an obsession with a woman named Beatrice.

On the morning of Saturday, the 4th of October 1986, members of the Ushiromiya family assemble on a nearby airport. Among those assembled are Kinzo’s second oldest child, Eva, her husband, Hideyoshi, and their child, George, as well Rudolf, Kinzo’s third child, Rudolf’s second wife Kyrie, and Rudolf’s son out of his first marriage, Battler, and lastly, Kinzo’s fourth and youngest child, Rosa, as well as Rosa’s daughter, Maria. These seven travel per airplane to nearby Niijima, where they meet up with Jessica, the daughter of Kinzo’s oldest son, and Kumasawa, one of the servants at Rokkenjima. They take a boat to Rokkenjima, arriving around 10:30 AM.

On Rokkenjima, the weather starts to show signs of getting worse. Traversing through the Ushiromiya family estate, the only part of the island that is inhabited by humans, they meet Godha, the ambitious and renowned private cook, and Kanon, a teenager and servant at the household, currently struggling to do heavy labour in the elaborate rose garden. The new arrivals settle into the guesthouse, separated from the main mansion by the rose garden. In the mansion, the final set of characters of importance to the story get introduced. Sayo, working under the servant name of Shannon, another young servant of the household, Krauss, Kinzo’s first child and heir-apparent to the Ushiromiya head family, and Natsuhi, Krauss’ wife and Jessica’s mother.[iii]

The children, i. e. the cousins, staying at the guesthouse, do some catching-up on their lives, while the parents, i. e. the siblings, discuss at the mansion. Between 12:00 PM and 1:30PM, the family and Nanjo assemble in the dining room of the mansion for lunch. Waiting in vain for Kinzo’s attendance, they proceed to eat without him. At around 1:30 PM, the parents withdraw to discuss finances and inheritance politics. Knowing that Kinzo is close to death, the question of who gets which part of the vast family fortune takes centre stage in their discussion. Accusing Krauss of embezzling some of Kinzo’s private fortune, namely the vast amount of it stored in a supposed ten tons of gold, Eva, Hideyoshi, Kyrie, and Rudolf (and Rosa to some degree) open with an offensive, demanding immediate compensation by Krauss. Denying the existence of the gold and shutting Natsuhi out of the conversation, Krauss counters, revealing that Rudolf is in desperate need of money because he is embroiled in legal battles in the United States, Hideyoshi and Eva are in need of money to support the shaky expansion of their business, and Rosa needs money for her fledgling business. Their talks ultimately end in a draw. Krauss later reveals to a distressed Natsuhi that the gold actually exists, showing a bar as proof.[iv]

Meanwhile, the children roam the mansion and later head down to the beach. They discuss a portrait hanging in the main staircase area, one that Battler had not seen since the last time he had been at Rokkenjima many years ago. The portrait supposedly shows the mystery woman, Beatrice, and has an epitaph underneath. Beatrice is known as the witch of the island, a myth Battler denounces as a fairy tale. The epitaph takes the form of a riddle, forecasting much death and tasking the readers with finding the hidden gold. On the beach, the children try to solve the riddle, also reminiscing on Kinzo’s biography and the history of the family fortune. While the Ushiromiya family had lost most of its wealth, means of production, and members in the Great Kantō earthquake of 1923, Kinzo rose to inherit the title of head of the family. By 1950, Kinzo had (re)established the family as one of the wealthiest of the country, having successfully gambled a lot of capital of mysterious origin on the Korean War. The children wonder if this mysterious starter capital might have been the gold, and if Beatrice might have been a mysterious financier that gave Kinzo this money. Maria, autistic child hyperfocused on the occult and dark magic, insists that Beatrice is a witch and had produced the gold using a “philosopher’s stone”.[v]

In the meantime, a massive storm that had been brewing for a while turns into first rainfall. At around 6:00 PM, Maria is still missing after having been hit in the face multiple times by Rosa a couple of hours earlier as a supposed disciplinary measure. The family goes searching for Maria. She is found in the rose garden, holding an umbrella, still looking for a singular rose plant she had taken a liking to when they first arrived at the island, scared that something might happen to the plant in the storm. Going on to look for whoever had handed Maria the umbrella to properly thank them, Maria insists that the umbrella had been handed to her by Beatrice. Furthermore, Beatrice, according to Maria’s description, had handed her a letter, to be read to the family. The letter, supposedly written by Beatrice herself, reminds them to solve the riddle of the epitaph, lest Beatrice collect what is owed to her according to a mysterious contract between Kinzo and her. Distressing over the letter, the adults continue to fight each other with words, up until midnight for some of them. In the meantime, George and Sayo, secretly involved with each other, meet up in the rose garden. George proposes to Sayo.

On the next day, at around 6:00 AM on the 5th of October, the machinery of the household springs to life again, while the storm still rages on. Preparing the breakfast is impossible, however, due to Godha being missing. As more of the guests and residents of the mansion and guesthouse wake up, it turns out that not only Godha is missing, but Sayo, Krauss, Rudolf, Kyrie, and Rosa as well. After Kanon discovers occult symbols written out in blood on the shutter of the rose garden storehouse, several characters rush to open it. Inside the storehouse are the corpses of all six that are missing, mutilated, especially in their faces.[vi] The family attempts to contact the police, but the telephones have failed in the storm, similarly, boats are no option.

Retreating to the mansion, they find the dining room covered in blood. Fearing for their lives, the survivors hole up in the parlor of the mansion at around 9 AM. Afterwards, they find Kinzo missing from his study. Everyone soon falls into suspicion of each other, suspecting a murderer in their midst, but also unable to rule out other parties, namely Beatrice, being involved. Especially Eva and Natsuhi begin fighting, while Natsuhi carries Kinzo’s rifle, the only known firearm on the island. In the meantime, the children, with the help of Maria, try to discuss the occult implications of the murders, and a new letter that had been found. At some point, despite Natsuhi’s reservations, Eva and Hideyoshi retreat to their guest rooms in the mansion.

At 7 PM, the servants discover the door to Eva and Hideyoshi’s room to be painted in blood. Prying the door open, they find the corpses of Eva and Hideyoshi, with strange spikes lodged into their foreheads.[vii] Smelling a strange smell coming from the boiler room in the basement, Kanon runs there. Challenging Beatrice, which he assigns to the darkness in the corner of the room, he tries to harm her, leading only to him being mortally wounded.[viii] It is difficult to decipher his final words, I personally do not understand if he had anticipated or at least accepted the potential of his death in that action. When everyone else catches up with him, it quickly becomes apparent that the smell is coming from the boiler, in which Kinzo’s charred corpse is found.[ix] The survivors retreat to Kinzo’s study, judging it to be the safest room in the mansion.

At around 8 PM, George, Battler, Jessica, and Natsuhi look at the smaller portrait of Beatrice on the wall of the study, when suddenly, another letter by Beatrice appears, in which Beatrice gleefully celebrates her victory. Suspecting those who had not looked at the portrait to contain Beatrice or at least a collaborator, Natsuhi sends out Nanjo, Genji, Maria, and Kumasawa.

At around 11:30 PM, the phone in the study rings, revealing a singing Maria. Sensing that she might have send the four others to their doom, Natsuhi goes looking for them. Their corpses are found in the parlor, safe for Maria, who stands to a wall, singing.[x] Natsuhi runs out to the main hall, when the clock strikes midnight. She challenges the darkness, Beatrice, to a duel, which leads to her being shot with the rifle she is carrying.[xi] The children arrive in the main hall to see a woman standing, half-shrouded in the dark, who Maria identifies as Beatrice, running towards her.

The next bit of story unfolds in the epilogue, written in the style of a historiographical account. The police arrive the next day, finding everyone dead, except the children, whose corpses could not be fully identified in the gore.[xii] An urban legend spawns from these two days at Rokkenjima. Some years later, a notebook fragment lodged inside a wine bottle washes ashore at a beach. It is a fragment of Maria’s diary, reporting on the events of the days, concluding in a cry not for help, but for the someone to solve the mystery at hand.

Concluding this embedded narrative, a new chapter called the Tea Party unlocks in the game’s menu. In the Tea Party, the first-order frame narrative unfolds, in a domain only labelled Purgatorio in the opening slide.[xiii] Kanon, Sayo, George, Jessica, Maria, and Battler converse about the events of the first Episode, fully aware that they are characters in a story. Most of them either believed in magic previously or now concede that magic must have been the murder weapon. Battler, however, resists this reading of events. Beatrice appears, superficially amused by Battler’s antics. Transporting them to the scene of Hideyoshi’s and Eva’s murder, she demonstrates supposedly magic mastery over so-called demonic stakes, with which she murders Hideyoshi and Eva again. Battler still does not concede, vowing to uncover what practical tricks Beatrice uses for her murders. The other children and young adults begin violently unravelling into piles of gore[xiv], as Beatrice magic keeping them alive supposedly fails as Battler is unable to believe in that magic. In her dying words, Jessica urges Battler to resist believing in magic.

Concluding the Tea Party, another chapter unlocks in the game’s menu. In this second-order frame narrative, in some ill-defined realm of witches, Beatrice hosts a witch named Bernkastel in her domain, inviting her to watch another game. While Beatrice is absent for a short while, Bernkastel turns her eyes and attention to the play-reader, giving, out of a self-reported pity for the play-reader, cryptic clues to playing/reading/observing Umineko. This concludes Ep1.

2. On apples falling from family trees, or: cyclical systems of violence

2.1 What the actual fuck, Battler: Rudolf, Rosa, parental violence, masculinity, and the patriarchy

The first thing that one can easily observe when reading Umineko Ep1 is that violence happens cyclically, on multiple levels. The violence Umineko examines is incredibly complex, with multiple threads interwoven into a singular system of power. A very fitting way to try to unravel these threads from one another (at least to some degree) is looking at the branches of the family tree placing allegorical emphasis on different aspects of that violence.

Much sooner than when the shutter is raised on the rose garden storehouse, Umineko Ep1 reaffirms that it is a horror game; more precisely, every third time[xv] Battler opens his mouth. For play-readers who get lulled into a false sense of security by the mundane family conversations at the airport, the harbour at Niijima reminds them of its horror when Battler makes jokes about sexually assaulting his cousin, Jessica. Later, he makes a joke about making Maria, his nine-year old cousin, promise that he can touch her breasts once he has grown up. This joke causes concern by George and Jessica. When Battler only shortly after sets out to touch Sayo’s breasts, Sayo does not resist, until she is directly ordered to do so. The characters around him barely acknowledge Battler’s insistence on semi-seriously performing symbolic acts of sexualized violence, only the joke with Maria leads to Jessica slapping Battler in the face, and the dynamic returns to friendly as quickly as it escalated. This absence of consequences for his violence stands for two things: How fundamental and normalized misogyny and the patriarchy are in the family, and that Battler is his father’s son. Indeed, that Battler mirrors in speech what his father enacts in material reality also stands as a pars pro toto for the fact that children in Umineko perpetuate the violence of their parents, with only minor variation per generation.

The extent of Rudolf’s patriarchal and sexualized violence is cloaked in hushes and whispers in Ep1, but the outline of his actions clings to his character. In his introduction at the airport, Kyrie and Battler joke about Kyrie being the only woman capable of holding Rudolf in his reigns; a metaphor of taming wild horses that seems to be close to common social narratives around particularly sexually violent men. Battler had left the family behind for about six years, angry at Rudolf for what Rudolf did to Battler’s mother, a mystery as of now. After the death of Battler’s mother, it took Rudolf not long to marry his former advisor-secretary Kyrie. Kinzo laments about his children and mentions Rudolf’s inability to control his lust. With a father like that, Battler’s sticking to mostly spoken jokes about misogynistic violence measures the distance the apple ultimately managed to fall from the tree.

That violence is an inheritance in the Ushiromiya family is very evident. This includes physical abuse. Rosa’s beating of Maria, for Maria speaking in a way perfectly normal for an autistic nine-year old, is one example of this. Indeed, this very overt act of parental violence also happens in the context of Maria searching for a singular, slightly wilting rose in the rose garden that she had taken a liking to. Engaging in improper speech patterns (read: making noises instead of using a sophisticated, class-appropriated lexicon) and showing compassion, things that all children engage in in some degree because (I cannot stress this enough) humans are born ultimately compassionate and playful, are met with extreme violence to be eradicated. The kind of adult growing up from such a childhood has to invest a lot of emotional energy in unravelling that violence and the trauma it causes. Those used to violence have a choice to either counter this violence by difficult means and heal, or perpetuate the same kind of violence. It is evident Rosa picked up her parenting methods from Kinzo, who is noted to have hit Krauss often and loudly as a child.

As violence is carried mostly undisturbed from generation to generation, misogyny becomes an integral aspect of the mechanism of violence. Battler notes that the Ushiromiya family places a special emphasis on blood relations, perhaps more than other families, but that focus on blood still includes the patriarchy to a large degree, just in an uncommon variation. Indeed, in parts of Ep1 focusing on Natsuhi, it becomes clear that especially women marrying into this family structure are seen as little more than means to produce heirs.

2.2 Class dismissed: Eva versus Natsuhi, the mansion, Gothic horror, and servants

Upon marrying into the Ushiromiya family, Natsuhi was expected to give birth to an heir to the head family as soon as possible. Indeed, she becomes reduced to her womb, in an incredibly dehumanizing fashion. Still, within the rigid social structure of the mansion, she is the host, the one every servant first turns to. When a servant is unable to perform their labour and present a perfect household, Natsuhi pays in social capital. As the connecting tissue between the servant class and the ultrarich family, as the outsider womb that failed for the longest time, as the silenced and excluded player in the parents’ game of inheritance splitting, Natsuhi takes a fringe position. She is a fulcrum of violence, both recipient and exacter of it. Nominally member of the uppermost class, and a woman, she should find herself on similar station to Eva.

And yet, in the incredibly weird and fully obscene tension between Eva and Natsuhi, Eva manages to mobilize class and blood relations to gain an advantage over Natsuhi. Eva managed to place Hideyoshi into the family registry, maintaining her family name despite that not being common, and upstages Natsuhi in fulfilling the role and purpose of a woman in this family structure, by birthing an heir faster than Natsuhi. Eva envies Krauss and wants to gain his level of power. George is Eva’s ambition grown into flesh, not a son but a pawn and argument, her project to produce a human more fit to the title of heir to the head family than Jessica. Indeed, Eva fully modelled George into that role, and most of the family agrees that he would make a better heir than Jessica. Natsuhi, maintaining a modicum of humanity and compassion despite the family around her, does not manage to exert the same level of violent force upon her daughter Jessica, leading to Jessica being labelled a failure, and Natsuhi in turn as well. Eva goes as far as calling Natsuhi a “lowly maidservant”. Natsuhi’s ambiguous state in the family comes also to be expressed in her not being allowed to bear the family crest, a one-winged eagle. While the servants and all (blood) family members are allowed to carry it on their clothes, Natsuhi is not afforded that status. Belittled over decades, torn from her old family and forced to cut all ties, reduced to a womb, called a failure time and time again, Natsuhi jumps at the opportunity when Kinzo tells her she is allowed to carry the one-winged eagle in her heart. Her desperation to become a full-fledged member of the family comes to a close when she, as the only surviving parent, calls herself heir to the family in her duel with Beatrice. This quest, to become full participant in the violent machinery of the family structure, fails, and she dies by the firearm so closely linked with the head of the family. And yet, the situation of the servants is markedly worse than Natsuhi’s.

While Natsuhi is dehumanized by being reduced to a walking womb, the servants are not even afforded a distant connection to flesh and blood, being reduced to furniture. It is a mantra beaten into them, one they repeat again and again to deny their own agency, to be “nothing but furniture”. The way the servants navigate this lack of agency varies. Genji consigns himself to collected and veiled pride; being most trusted by Kinzo, moreso than Kinzo even trusts his own children. Godha, not unlike Natsuhi, tries to integrate himself into this power structure, but unlike Natsuhi, he is not tied down by regret, pain, and a modicum of humanity. He steals what little social capital is afforded to the servants for himself, assigning them much less prestigious tasks. And yet, he ends up destroyed in the same machinery of power he tried to kiss up to, being one of the first to die. Kumasawa withdraws herself from difficult labour, and tells stories and lies and uses a semblance of a jester’s freedom to protect the young servants as best as she can. Sayo freezes in inaction and despair. And Kanon, the youngest, reacts ultimately in an outburst of righteous anger. One must note the degree of violence of class that is enacted upon mere children. In an act veiled in the narrative of philanthropy, Kinzo recruits little children from orphanages to work at the household. This is praised as a chance for them to make money, and to raise in social status. In reality, Kanon’s introduction, in which he fails at performing incredibly hard labour in the garden, shows that Kinzo employs child labour to upkeep his machinery of family as enshrined by the building of the mansion. Once again, violence is exerted upon children to force them into a new generation of this cycle.

The mansion itself is a symbol that can be read in multiple ways, two of which are yet to follow; but it is a very evident expression of power. The ability to buy the rights to an entire island and build a massive mansion complex on it, one large enough to fit a miniature version of itself – Kinzo’s study being called a mansion inside a mansion at some point – is of course an expression of class. Elaborate rooms in the upper floors assigned to be only walked by the high and mighty, and the utilities assigned down below to be only visited by the servants – the structure of the mansion uses its walls to create and reinforce borders and delineations between the classes. These borders only fall, servants walking main rooms and the rich seeing the utilities up close, when Rokkenjima’s violence becomes unable to be narrated away as actual blood and gore runs through its halls.

A potentially supernatural murder series inside a western style mansion could be read as a marker of genre, even – but Umineko Ep1 resists strict allegiance to a singular genre. It toys with the elements of Gothic horror – of which the mansion as a stage and ordering device is a central one – but also transcends it. The origins of Gothic horror in the late 19th century, from what little I know about literary history, do treat their servants as actually nothing more than furniture, barely mentioned if all, not counted as human. Umineko’s supposed furniture cries, curses, bleeds, resists, gives in, dreams of love, stands together and aside. Umineko’s servants navigate class and agency, and that navigation takes centre stage multiple times, their inability to throw their own humanity and compassion away underlining and inverting the parents’ demand to ignore notions of compassion and humanity. But the mansion, particularly its position on an island otherwise uninhabited by humans, takes on multiple roles at once.

2.3 Pecunia non olet: Krauss, resource extraction, ecology, and the storm

The mansion and its surrounding area are an exception to the typical structure of Rokkenjima. Rokkenjima is densely inhabited and brimming with life, but not of the human variety. It is marked by a dense forest, and its cliffs are home to the black-tailed gulls who mark the text’s title – they are the Umineko, a common seabird found across many Pacific coasts, particularly in East Asia. The absence of their distinctive cry upon the visitor’s arrival on the island is remarked upon in the text, and it is one of the many early indicators of the impending tempest that entraps the island for two days. As the gulls notice changes to the wind patterns, humidity, and air pressure, they instinctually withdraw to safer locations to sit out the storm. Once they cry again, the storm has passed.

The mundane black-tailed gulls are in several ways a counterpart and mirror to the seemingly majestic one-winged eagle. Whereas the gulls have (probably) existed on Rokkenjima since its distinct geo-ecological formation as an island, the one-winged eagle specifically as the symbol of the Ushiromiya family has rested on Rokkenjima only since Kinzo manoeuvred himself into de-facto legal possession of the island. As Battler remarks at some point:

“Buying an entire island is not something that you can ordinarily do today. However, Grandfather was clever. He contacted the GHQ and applied for the establishment of a marine resource base. He acquired this island as a business property, then tossed that project aside and claimed it as his own plot of land. [...] Later, Tokyo made difficulties by telling Kinzo to return the land, but the pushy GHQ intervened. Grandfather, with considerable skill and good luck, managed to weather the stormy seas of that period, obtaining a vast fortune and his own island. [...] A mansion was built on the island soon after. [...] Grandfather, with his love of the Western style, made this once uninhabited island a canvas upon which he could realize his dreams to his heart’s content. He now had the Western mansion of his dreams, overflowing with emotion and atmosphere, and a beautiful garden featuring all sorts of roses. And he had a private beach where nobody other than himself would ever be permitted to leave a footprint.”

There is a lot – a lot – going on this passage, and I will come back to it in section 2.4, but for now, there is one focus point: The island is described by Battler as having been previously uninhabited. This draws, at minimum, a line in which a distinct human presence is conflated with the state of being uninhabited. Rokkenjima, before Kinzo’s arrival, so the narrative spun by Battler, exists as a social and ecological terra nullius, this “empty canvas”, into which Kinzo inscribed his personal vision. This passage continually reaffirms the notion that land can be viewed through the lens of ownership – which far from a neutral idea.

By turning the land into something that can be “obtained”, “bought”, and “claimed” by a singular individual, its ecology is exposed to the logics of neoliberalism. And, indeed, Kinzo’s eldest, the designated heir to the financial empire, Krauss, doubles down on this process. The guest house is a symbol of Krauss trying to extract monetary value from the idea of land ownership: He plans on turning the island into a vacation resort for well-paying customers. As Rudolf comments on Krauss’ plan:

“You were brilliant when you saw that using this island only as a place to live was a waste. I think it was a pretty good plan to turn it into a resort that could use the prospect of marine sports, fishing, honeymoons and the like to attract customers. If I were the oldest son, I’m sure I’d have strained my brain looking for a way to make profit off this island.”

Later, Rudolf adds:

“I’ll bet you want to liquidate but can’t. After all, there’s no reason for anyone to buy such an extravagant hotel on an isolated, empty island without any established sightseeing routes.”

An island existing on its own, as an ecologically closed system by itself, is an impossibility under capitalism. Value must be extracted from everything, even the fact of land and ecology itself, else, it is, as Kinzo’s children seem to unanimously agree, a “waste”. Rokkenjima, so full with dense forestry and filled to the brink with life is “empty” because humans cannot make more money out of it. Establishing sightseeing routes, cutting through the ecology to maximize human access – and human profit – to and from it, is the only way not to “waste” it. The black-tailed gull is not granted any meaningful connection or presence on the island. And yet, on the morning of the 6th of October, the skies clear, and the black-tailed gulls cry again, alive and present on the island, whereas those who previously so proudly wore the one-winged eagle lie slaughtered into piles of blood and gore across the mansion and garden.

Kinzo’s fortune – not coincidentally – is maintained through having invested his money during the Fifties into the iron and steel industry, key actors in material resource extraction and environmental devastation, also given the connection of the steel and coal industries. The influence the economic system has on the ecology is marked by resource extraction. When it is a tropical thunderstorm that entraps the Ushiromiya family on this island it previously called its possession, forcing everyone to meet their violent demise, there is a certain comedic catharsis to it – thunderstorms, their increasing likelihood and extremeness, are a direct result of the economic mechanisms that marked the Ushiromiya ascension to power. For all their money, the Ushiromiyas cannot escape the storm. By exploiting nature they rise, by being unable to control such a large natural event they fall.

The theme of the Ushiromiyas’ fall repeats in the ecology, not only being found in the fauna but also in the flora. The rose garden is part of Krauss’ “development” of the land as well as Kinzo’s self-inscription onto the island. It is a model of making sense of nature – whereas the Ushiromiyas describe the forest of Rokkenjima as uninviting, dark, and imposing, the rose garden is a source of respite, admiration, and a stage upon which their control is played out. But the garden is far from a fitting presence on the island – it is noted multiple times that the yearly thunderstorms devastate the garden, leading to it requiring major repair and replanting every time. Rokkenjima is not a natural habitat for roses – and yet, as a mark of pride and possession of nature, it has to be repeatedly reinstated on it. And yet, after the storm passes, the trees of Rokkenjima still stand, whereas the roses of the Ushiromiyas have been scattered and largely destroyed. It is just as fitting to underline the Ushiromiyas’ relationship to the ecology around them that Maria’s concern for the well-being of a singular rose – an entirely positive process in which two organisms interact in a caring and gentle way – is seen as childish and absurd, whereas establishing a rose garden on Rokkenjima in the first place is seen as logical and meaningful.

Turning from the text to the real world, there is an actual and vast touristic network spanning the Izu islands. There is reason to assume that Krauss’ plans might have been fruitful if it were not for his face being separated from the rest of his body. Then again, the Izu islands also feature a long history of hotel ruins and closed tourist resorts – a very interesting example being the Hachijō-jima Royal Hotel, a project very similar to Krauss’, just some decades prior. Also featuring a sizable hotel complex in the Western style, it is now an abandoned ruin, having closed in 2006 (see Lowe, 2016). More importantly, the Japanese government used to advertise this hotel as the “Hawaii [sic!] of Japan”, a marketing pitch that, according to David Lowe, saw success at the time (2016). Let us put a pin on the mobilization of an image of Hawai’i by Japanese government actors, and turn from the branches of this rotten family tree to its roots and finally fire Chekhov's Winchester M1894.

2.4 How to get away with fascism: Kinzo, imperialism, occultism, cowboys, the nonexistent philosopher’s stone, and (hi)storytelling

This reading of the Ushiromiya family so far has purposefully taken individual members to underline larger system, but of course, this choosing-of-focus is an artificial fragmentation. Eva’s ambition overlaps with Krauss’ neoliberalism. Rudolf’s misogyny overlaps with Eva’s attempts to push Natsuhi down. Rosa’s explicit violence against Maria overlaps with Eva’s implicit violence against George. I cherry-picked aspects of their violence that seemed to stick out as an illustration, but they all orbit around the same centre of gravity, the source of it all: Kinzo.

Multiple times in Ep1, the Ushiromiya family history gets narrated, specifically, surrounding Kinzo’s financial decisions. Every time, the story starts at the Great Kantō Earthquake of 1923[xvi], and ends around 1950, with the start of the Korean War. During the earthquake, the family is said to have lost their means of production, having been industrialists beforehand, and having lost several members, leading to Kinzo’s unlikely ascension to the head of the family. Kinzo is said to have acquired some starter capital in the form of a massive amount of gold before 1950, very early going all in on some form of Korean War bonds, being called Korean War Demands in the text. Kinzo is in these descriptions universally praised for his cunning, willingness to take risks, cooperation with the West, and seemingly inhuman foresight. Let’s reexamine this story again: A Japanese former industrialist rebuilds his family’s fortune between 1923 and roughly 1950, by acquiring gold of mysterious origins in between that timeframe. In the text, the adults speculate that Beatrice might have been a mysterious widowed financier willing to support Kinzo, whereas Maria insists that Beatrice used black magic – the philosopher’s stone, specifically – to create gold out of nothing. But this story of the family fortune is painfully familiar to me as a historian capable of speaking and reading German. Now, class, can anyone tell me what might have happened in these less than three decades that a sufficiently violent man could have used to make a small fortune out of nothing?

When I commented in the Discord chat that I use to ramble about Umineko on exactly that fact after the first time the financial history of the family was narrated, and called Kinzo a fascist, Ozaawa confirmed my conclusion. The Ushiromiya family gold – the source of it all, Kinzo’s great legacy – stems from fascist sources. The mysteriously lacking narration of the company history for the Thirties and Forties aside, there is another factor to consider to point towards this conclusion as early as the middle point of Ep1. When Krauss shows Natsuhi an actual bar of the family’s gold reserves, Natsuhi notices the absence of a note of the forge/bank that is customary for high-quality gold bars. All that the gold bars show is a one-winged eagle. Now, of course you can think of the philosopher’s stone all you want, and deliberate how gold bars created from magic might look – but unmarked gold acquired in the Thirties and Forties could be explained by much less magical origins. The eagle itself is a symbol mobilized by many fascists the world over – its role as a symbol for the Ushiromiya family hints further towards the origins of that fortune.

The supposed mystery of the gold’s origin only becomes less mysterious when considering what means of gaining wealth are fully accepted as legitimate parts of the family history. The Korean War Demands – some way of profiting of the Korean War – are seen as a masterful stroke by Kinzo. That the Korean War was an incredibly bloody proxy war between the US-American and Soviet Empires, one fought with a land and population as collateral that had been violently occupied by Imperial Japan for decades prior, makes no difference. Kinzo’s war profiteering in 1950 is a socially acceptable form of imperialism, whereas the source of the gold is not. That Kinzo simply changed which imperialists to support between 1940 and 1950 does not change that he is profiteering of it in some capacity or another. His supposed cunning as a businessman is nothing more than a keen understanding of which empire will win and lose in which conflict combined with a willingness to turn the blood spilled by imperialism into gold.

Speaking of spilling blood, the murders of Rokkenjima are, as elaborated in the introduction, called “the demon’s roulette” in the text on multiple occasions, referring to some obscure black magic ritual. Magic and the occult are, so it is said by several people at multiple times in the text, bound by the logic of miracles. Kinzo explains it as such to Kanon:

“In other words, magic is a game. It is not the case that the one who performs the best becomes the victor. The victor performs the best because he has been granted magic. [...] Of course. I made it difficult. ...But you must try to solve it as well. That will form the seed that summons the miracle of my magic. If every one attempts it and everyone fails, that will be that. However, if the miracles come together and give birth to magical power, it will happen! [...] That is why you must attempt it too. Everyone must attempt it. And in so doing, they will give strength to my magic!! Do you understand?!”

Kinzo’s magic trick requires unfaltering belief in the riddle of the epitaph. Everyone, no matter of which background, can solve the riddle of the epitaph, a riddle that promises those who solve it wealth in the form of gold, and everyone must attempt to do so. The neoliberal credo is that everyone must use their own cunning and skill to strive for wealth, and that everyone can ascend to wealth when they are cunning enough. The demon’s roulette, as a pars pro toto for black magic and the occult, operates noticeably in parallel to the logics of capitalism. The occult as explained by Kinzo, in this reading of Ep1, therefore becomes a mirror to imperialist capitalism – capable of withdrawing it from the narratives that cloak it and obscure its violence, the demon’s roulette embodies and demonstrates the violence necessary to operate imperialist capitalism. It is easy for the characters to think of the gold as a distant, clean commodity and bargaining chip. It is easy for me to describe that the text alludes to the origins of the gold in fascism and imperialism. But when Battler breaks down in tears at the sight of his parent’s disfigured and defaced corpses, when the blood and gore of everyone mixes so much that class distinctions break down just as much as the bodies, when the eldest and most powerful man and the youngest, abused servant both lie in death and dead in the same room, the demon’s roulette unveils what stands behind the Ushiromiya wealth: blood. Rudolf’s negotiation with Krauss features the only mention of roulette in the text that I noticed that is not the demon’s roulette:

“The iron rule of the money roulette is that you bet against the loser.”

The demon’s roulette is the money roulette. Capitalism and imperialism operate like the occult in the embedded narrative of Ep1 does, just with one being more socially accepted than the other. Just as the violence of the occult fails and falls apart when people’s belief in it shakes, so does capitalism.

In the end, the family tree planted by Kinzo bears the fruits he has ultimately sown. Is not Eva as manipulative and emotionally violent as him? Does his obsession with Beatrice not speak the same language as Rudolf’s misogyny? Is Krauss’ money-making not just as random and based on chance as his? Does Rosa not beat her own child like he beat his? When Kinzo laments how horrible his children are, is he clairvoyant enough for that to be self-hatred? The violence that marks the Ushiromiya family stems from imperialism and fascism and capitalism in all their entanglements, made manifest in the structure of the family and mansion.

A perfect illustration of this is the symbol of the Winchester M1894. It is a gun featured in western Westerns, a motive that keeps reappearing. Being the actual gun used in filming some Western[xvii], Kinzo had it bought and retrofitted to his liking. Kinzo, so is reaffirmed many, many times in the text, is obsessed with the West. His ability to schmooze up to the GHQ is just one example of this. Kinzo, the Japanese imperialist, being close to the West, is yet another pars pro toto; Japanese imperialism has historically grown in close proximity to Western imperialism. With the end of the Shogunate and the beginning of the Meiji restoration, the idea of industrialization and restructuring of society after the western model laid the ideological groundwork for building imperial Japan; particularly, the contact point of the Pacific brought Japan into connection with the United States, extending its Empire by the annexation of the Kingdom of Hawai’i. That Japanese government agents used the idea of the US tourist industry in Hawai’i – an inextricable part of imperial control and domination – to promote a hotel resort on an actual island close to where Rokkenjima would be in the real world, ties Krauss’ island development project back to Kinzo and Kinzo’s obsession with the West. He has a western-style mansion, a western-style rose garden, his children have western-style names, and he has a western-style Western rifle. The idea of the cowboy in the genre of the Western is one inherently tied to US myths of westward expansion and manifest destiny. If the rifle then symbolizes the cowboy, and one questions the context of the genre where the cowboy is the protagonist, it becomes a tool of violent colonial inscription. Rokkenjima becomes Kinzo’s colonial playground, one which he violently claims and violently maintains while wielding the cowboy’s gun, one modified to his liking. It is western imperialism with a small twist, retrofitted for the logics and specific situation at play in Rokkenjima. Natsuhi dies, claiming the rifle and the title of head of the family, shot by the instrument of imperialism she could, in the end, not wield properly.