#yale center for british art collection

Text

David Garrick and His Wife by His Temple to Shakespeare at Hampton, Johan Zoffany, ca. 1762

#art#art history#Johan Zoffany#landscape#landscape painting#England#portrait#portrait painting#Neoclassicism#Neoclassical art#German art#Anglo-German art#18th century art#Yale Center for British Art#Paul Mellon Collection

114 notes

·

View notes

Photo

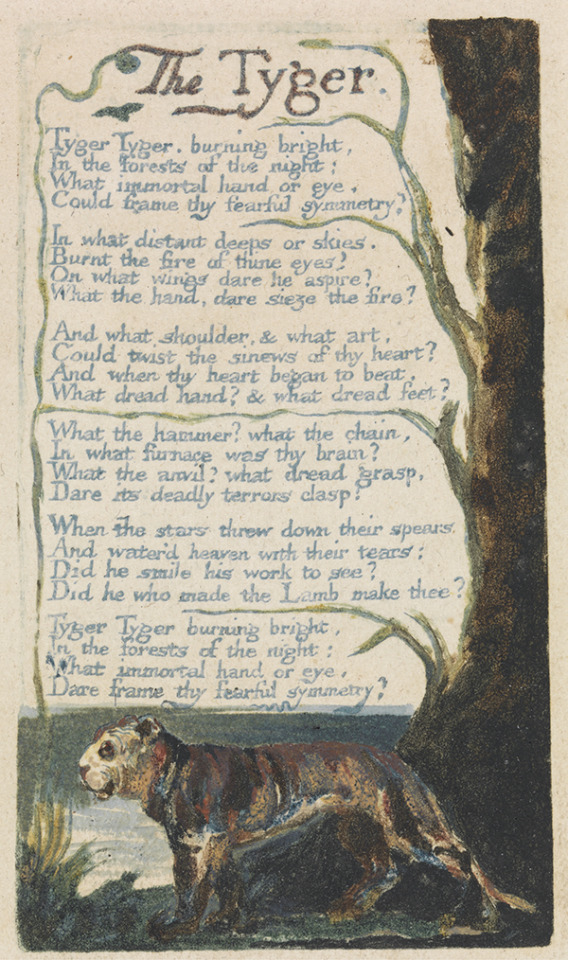

William Blake, “The Tyger.” Songs of Innocence and of Experience copy F (1789, 1794). Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection. B1978.43.1573.

965 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy #InternationalZebraDay! Here are a 1751 George Edwards illustration and a 1763 George Stubbs painting depicting the first zebras seen in Britain: a now extinct Quagga (Equus quagga quagga), and a rare Cape Mountain Zebra (Equus zebra zebra), which also was almost driven to extinction but has thankfully since recovered.

1. The Female Zebra

George Edwards (English, 1694-1773)

hand-colored copper-plate engraving dated 1751

published in Edwards’ Gleanings of Natural History Pt. 1 in 1758 as Plate 223Wellcome Collection

2. Zebra, 1763

George Stubbs (English, 1724–1806)

oil on canvas

Yale Center for British Art

More on the blog: https://arthistoryanimalia.com/2023/01/31/animal-art-of-the-day-for-international-zebra-day-1-george-edwards-george-stubbs-and-the-first-british-zebras/

#zebra#zebras#equids#mammals#European art#illustration#painting#book illustration#engraving#print#works on paper#18th century#British art#International Zebra Day#extinct species#Quagga#animals in art

299 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Early 1730s dresses and portraits (from top to bottom) -

ca. 1732 The Beautiful Greek (La Belle Grecque) by Nicolas Lancret (Wallace Collection - London, UK). From their Web site 1429X1960, The complex sleeves open at the top like they would in Russian court dresses a century later.

ca. 1732 Watson-Wentworth and Finch Families by Charles Philips (Yale Center for British Art, Yale University - New Haven, Connecticut, USA) persons. From Wikimedia 4902X3094. The décolletage-filling fichu would become prominent in the Louis XVI era, but just about every grown up woman wears one along with a fastened bodice, round skirt, and apron. The heads of every female are covered by a cap, veil, or hat.

1733 Marie-Geneviève le Tonnellier de Breteuil by French school (attributed to Alexis Simon Belle) (auctioned by Sala de Ventas).From invaluable.com/auction-lot/18th-century-french-school-alexis-simon-belle-a-646-c-2074af1b03 1940X3362.Round skirts flourish on both shores of the channel.

ca. 1730-1735 Lady by Joseph Highmore (National Gallery of Art - Washington, DC, USA). From their Web site 1148X1495. The cuffed outer sleeves are stuffed by under-sleeves and the dress lining has a very subdued pink contrasting with the gold color of the other layer.

1734 Princess Sophie Dorothea with Friedrich Wilhelm by Antoine Pesne (location ?). From Wikimedia1633X2611. Textiles with large patterns characterize the early 1700s. Her dress has a square neckline.suggesting French influence.

ca. 1734 Wilhelmine of Prussia, Margravine of Brandenburg-Bayreuth by Antoine Pesne (location ?). From Wikimedia 829X11221. The silver brocade over-bodice has a deep V neckline filled in with scoop neckline.

1734 Madame Marie du Tour Vuillard (1695- 1759), née Robin by Louis Michel Van Loo (Tajan - 12-12-12 auction Lot 37), From their Web site; fixed spots & flaws w Pshop 2487X3151.

#1730s fashion#Georgian fashion#Louis XV fashion#Rococo fashion.#The Beautiful Greek#Nicolas Lancret#fur-trimmed dress#Charles Philips#Marie-Geneviève le Tonnellier de Breteuil#Alexis Simon Belle#curly hair#tabbed bodice#Joseph Highmore#Princess Sophie Dorothea#Antoine Pesne#Wilhelmine of Prussia#Madame Marie du Tour Vuillard#Louis Michel Van Loo#wire cap#lace choker#fur trim

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

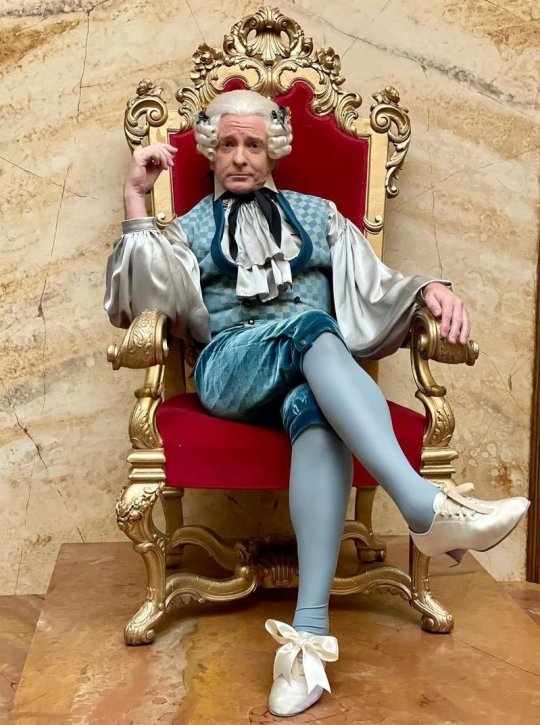

OFMD Stede Bonnet as a Macaroni: Wealth, Gender and Sexuality in the 18th Century Fashion World

Historical Inaccuracy in Our Flag Means Death? Never!

Historical inaccuracy! I hear you cry. A Macaroni in 1717!?! It is true macaroni fashion was really a late-18th century fashion trend, seemingly reaching its peak in the 1770s. However Our Flag Means Death is nothing if not historically inaccurate. Stede’s costumes seem to take inspiration from across the 18th century rather than worrying about what would have actually been worn in 1717.

Early 18th century suits tended to have round necklines, loose-fitting sleeves with wide cuffs, long waistcoats that stoped just above the knee, and coats with full skirts just a little longer that the waistcoat.

[Left: Matthew Prior, oil on canvas, c. 1713-1714, by Alexis-Simon Belle, photo credit: St John's College, University of Cambridge, via Art UK.

Middle: Matthew Hutton of Newnham, Hertfordshire, oil on canvas, c. 1715, by Johannes Verelst, photo credit: National Trust Images, via Art UK.

Right: William Leathes, Ambassador Brussels, oil on canvas, c. 1710-1711, by Herman van der Myn, photo credit: Colchester and Ipswich Museums Service: Ipswich Borough Council Collection, via Art UK.]

As the century continued we get standing collars and turned down collars but round necklines were still around as well, sleeves got tighter with smaller cuffs, the waistcoats got shorter and the coats lost their skirts.

[Left: Thomas ‘Sense’ Browne, oil on canvas, c. 1775, by Nathaniel Dance-Holland, photo credit: Yale Center for British Art, via Art UK.

Middle: Sir Brooke Boothby, oil on canvas, c. 1781, by Joseph Wright of Derby, photo credit: Tate, via Art UK.

Right: David Allan, oil on canvas, c. 1770, by David Allan, photo credit: Royal Scottish Academy/National Galleries of Scotland (Antonia Reeve), via Art UK.]

Stede’s collars are inconstant some are rounded but others are turned down and Ed’s purple suit has a standing collar. Many of Stede’s coats have wide cuffs, but most have little skirt to them. His teal suit from the pilot has a bit of a skirt but its paired with a short waistcoat.

Most of Stede’s waistcoats are short with the exception of his suits from both the wedding portrait with Mary and the the family portrait. Both suits are very straight giving him a boxy appearance and are pretty different from most of the suits we see him in.

All in all I don’t think they were aiming for historically realistic clothes but with the collars, short waistcoats, and lack of skirts I get more of a late-18th century vibe.

So what was a Macaroni?

A Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue (1785), defined macaroni as follows:

An Italian paste made of flour and eggs; also a fop, which name arose from a club, called the maccaroni club, instituted by some of the most; dressy travelled gentlemen about town, who led the fashions, whence a man foppishly dressed, was supposed a member of that club, and by contraction stiled a maccaroni.

The macaroni club was said to have comprised of young men who had gained a taste for French and Italian textiles on their Grand Tour (a traditional trip taken tough Europe by upper class men when they came of age). The earliest reference to the club is from a letter from Horace Walpole to Lord Hertford on the 6th Feb 1764:

at the Maccaroni Club (which is composed of all the travelled young men who wear long curls and spying-glasses),

In his book Pretty Gentleman: Macaroni Men and the Eighteenth-Century Fashion World Peter McNeil suggest the club was actually Almack’s. Almack’s was a private club at 50 Pall Mall that was attended by prominent Whigs including Sheridan, Fox and the Price of Wales. (p52) While the name may have originated from the men at Almack’s it was soon used to describe any man who followed the associated fashion trends.

So what were these trends?

Hair

“Still lower let us fall for once, and pop

Our heads into a modern Barber’s shop;

What the result? or what we behold there?

A set of Macaronies weaving hair.”

~ The Macaroni by Robert Hitchcock

Probably the most iconic aspect of macaroni fashion was the hair. “It was the macaroni attention to wigs that caused most consternation” explains Peter McNeil. The macaroni hair “matched the towering heights of the female coiffure, with a tall toupee cresting at the centre front. The wig generally had a long tail at the neck (’queue’), which when folded double was called the ‘cadogan’, all of which required regular dressing with pomade and powder, sometimes in the colours of pink, green or red.” (p45)

The height of the macaroni hair was a point of particular fascination in macaroni caricature exaggerating it beyond what the macaroni were probably actually wearing. Compare below Tom’s hair in the satirical print What is this my son Tom to the self portrait of Richard Cosway, who was satirised by Mary Darly as “The Miniature Macaroni” (a reference both to his height and his career as a miniature painter).

[Left: What is this my son Tom, print, c. 1774, published by Sayer & Bennett, via The British Museum.

Right: Self-Portrait, Ivory, c. 1770–75, by Richard Cosway, via The Met.]

The way Stede usually wears is hair is not particularly macaroni nor particularly 18th century for that matter. The exception to this is his wig from The Best Revenge Is Dressing Well though even this doesn’t have the iconic macaroni hight.

Interestingly both Stede and Ed are wearing flowers in their hair. While there are certainly depictions of women with flowers in there hair I’m not aware of this being a trend in mens fashion at all. However macaroni were known for wearing large nosegays.

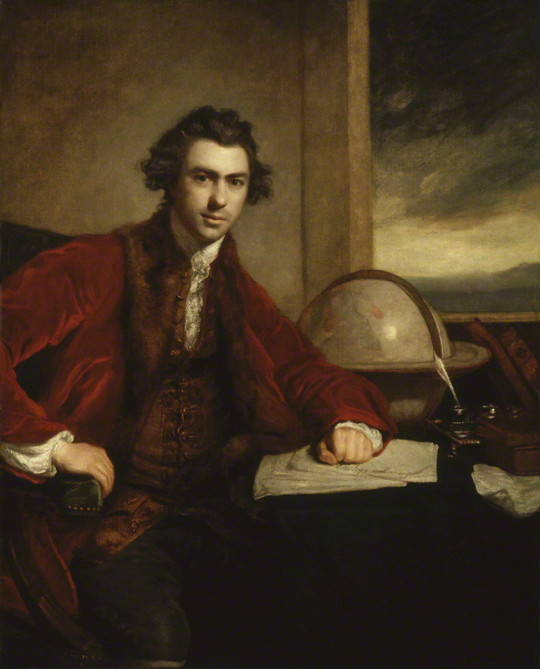

While the tall hair was certainly iconic not all macaroni wore their hair tall. Joseph Banks, who was satirised as “The Fly Catching Macaroni” by Matthew Darly, is depicted in his portrait with a fairly typical 18th century hairstyle. Its not the hair alone that makes a macaroni, it was just one aspect of the fashion.

[Sir Joseph Banks, oil on canvas, c. 1771-1773, by Sir Joshua Reynolds, via Wikimedia.]

Suit

“If I went to Almack’s and decked out my wrinkles in pink and green like Lord Harrington, I might still be in vogue.” ~ Horace Walpole to Lord Hertford, 25 Nov 1764

Menswear of the period consisted of the same basic elements; shirt, stockings, breeches, waistcoat and coat. What differentiated the macaroni from others was the fabric, cut, colour and trimmings of the suit. “At a time when English dress generally consisted of more sober cuts and the use of monochrome broadcloth,” explains Peter McNeil “macaronism emphasised the effects associated with French, Spanish and Italian textiles and trimmings”. Popular amongst macaroni were brocaded and embroidered silks and velvets, sometimes further embellished with metallic sequins, simulated gemstones and raised metallic threads. Popular colours included pastels, pea-green, pink, red and deep orange. (McNeil, p30-32)

Far from wearing “monochrome broadcloth” Stede likes a “fine fabric” and dresses in a range of colours, we see him in teal, pink, purple, green, white, red, peach &c.

Tightly cut French style suits known as habit à la française were popular with macaroni. (McNeil, p14) Stede’s suits vary somewhat in cut but some are very French. The peach suit Stede wears in We Gull Way Back particularly has a very macaroni feel to me. Compare it to the English suit (left) and the French suit (right).

From the back you can see the English suit has more of a skirt to it.

Both Stede’s suit and the French suit are somewhat plain but have been paired with a floral embroidered waistcoat, while the English suit has a matching plain black waistcoat.

[Left: English suit, wool, silk, c. 1755–65, via The Met, number: 2009.300.916a, b.

Right: French suit, Silk plain weave (faille), c. 1785, via LACMA, number: M.2007.211.47a-b.]

Fabric covered button’s were common in the 18th century, you can see them on both the French and English coats above. In contrast Stede wears a lot of metal buttons. Steel buttons were popular amongst macaroni, a trend that was satirised in Steel Buttons/Coup de Bouton.

[Steel Buttons/Coup de Bouton, print, c. 1777, by William Humphrey, via The British Museum.]

Pumps and Parasols

“Maccaronies who trip in pumps and with Parasols over their heads” ~ Mrs Montagu

High heels had been popular amongst men during the 17th century. The Royal Collection Trust explains:

In the first half of the 17th century, high heeled shoes for men took the form of heeled riding or Cavalier boots as worn by Charles I. As the wearing of heels filtered into the lower ranks of society, the aristocracy responded by dramatically increasing the height of their shoes. High heels were impractical for undertaking manual labour or walking long distances, and therefore announced the privileged status of the wearer.

(Royal Collection Trust, High Heels Fit for a King)

In 17th century France Louis XIV popularised red-heels by turning them into a symbol of political privilege, which in turn spread the fashion to England. But with the sobering of menswear in England around the turn of the century the high heel and the red-heels went out of fashion. (see Bata Shoe Museum Toronto, Standing TALL: The Curious History of Men in Heels)

The high heel had a bit of a resurgence in the 1770s with macaroni fashion. The Natural History of a Macaroni snipes that the macaroni’s “natural hight is somewhat inferior to he ordinary size of men, through by the artificial hight of their heels, they in general reach that standard”. (Walker’s Hibernian Magazine, July 1777, p458)

Red-heels were reintroduced to England by young men returning from their Grand Tours. A young Charles James Fox (satirised by Mathew Darly as “the Original Macaroni”) wore such French style red-heeled shoes. The Monthly Magazine recalls a young Fox as a “celebrated “beau garçon” with “his chapeau bras, his red-heeled shoes, and his blue hair-powder.” (Oct 1806) and The Life of the Right Honorable, Charles James Fox recalls him in his “suit of Paris-cut velvet, most fancifully embroidered, and bedecked with a large bouquet; a head-dress cemented into every variety of shape; a little silk hat, curiously ornamented; and a pair of French shoes, with red-heels;” (p18) And in Recollections of the Life of the Late Right Honorable Charles James Fox B.C. Walpole recalls him as “one of the greatest beaus in England,” who “indulged in all the fashionable elegance of attire, and vied, in point of red heels and Paris-cut velvet with the most dashing young men of the age. Indeed there are many still living who recollect Beau Fox strutting up and down St. Jame’s-street, in a suit of French embroidery, a little silk hat, red-heeled shoes, and a bouquet nearly large enough for a may-pole.” (p24)

Compare the French style red-heeled shoes of Louis XIV to Stede’s red-heeled shoes.

[Left: detail of Louis XIV, oil on canvas, c. 1701, by Hyacinthe Rigaud, via Wikimedia.]

However most macaroni were depicted wearing the more standard late 18th century low-heeled bucked shoes. Where they distinguished themselves was the size and decoration of the buckles. “Such buckles could be set with pate (lead glass) or ‘Bristol stones’ (chips of quartz), or diamonds if you were very rich.” Explains peter McNeil, “The new macaroni fashion was for huge silver or plated Artois shoe buckles which the Mourning Post claimed weighed three to eleven ounces.” (p90)

While certainly not as iconic has his heels Stede also wears these sorts of shoes. Compare below the shoes from a macaroni caricature to Ed wearing Stede’s shoes (I couldn’t get a good shot of Stede wearing them).

[Left: detail of How d'ye like me, print, c. 1772, published by: Carington Bowles, via The British Museum.]

“A great many jewelled accessories accompanied the macaroni look”, writes Peter McNeil, “They included hanger swords, very long canes, clubs, spying glasses and snuff-boxes.” (p68) Tragically we don’t see Stede with a fashionable dress sword or a cane but we do see him with another accessory popular amongst macaroni; a parasol.

Popular in France parasols/umbrellas were adopted by the macaroni. They were popular amongst both men and woman in France but in England they had a feminine connotation. (McNeil, p129) In the 1780s as umbrellas became more popular amongst men there was a cultural pushback to the perceived gender transgression. On the 16th of August 1780 the Morning Post complains of of the “canopy of umbrellas” bemoaning that “the effeminacy of the men, inclines them to adopt this necessary appendage of female convenience”. On the the 4th Oct, 1784, the Morning Chronicle published a letter complaining of “that vile foppish practice of sheltering under a umbrella”. The author of this tirade writes that while “the ladies should be allowed to secure their beauty and persons from the heat of the sun, or the inclemency of the weather,” because “it is natural, and has a striking effect”, that “to see a great lubberly cit, bounce from his shop, with a coat, hat, and wig that are not together worth one groat,” sheltering “from the influence of the solar beam” was “intolerable.” However:

The macaroni being of the doubtful gender, may in part claim a feminine right; his dress is too delicate to bear an heavy shower, perhaps his person is so too; but a coach, if a clean one is to be found would serve his purpose much better, as there would be less likelihood of his being washed away into the kennel, which he deserves to be kicked into for his d-----d affectation.

Wealth

Born from rich young men returning from their tours with a taste for French and Italian textiles macaroni fashion was expensive. Certainly a working class man would not be able to afford Stede’s wardrobe. Both the sheer amount of clothes he has as well has the fabrics those clothes are made of are indications of wealth. However to say that Stede’s wardrobe is only an indication of wealth would be missing part of picture.

Most rich upper class English men (including colonial) wore plain monochrome suits. Even amongst the gentry macaroni fashion was not the norm. Compare bellow George Washington (left) who was a wealthy planation owner, but notably not a macaroni, to Richard Cosway (right) who was a famous macaroni.

[Left: George Washington, oil on canvas, c. 1796, by Gilbert Stuart, via Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.

Right: Detail of The Academicians of the Royal Academy, oil on canvas, c. 1771-72, by Johan Zoffany, via The Royal Collection Trust.]

In spite of the expense macaroni fashion was not exclusive to the upper classes. “Macaroni dress was not restricted to members of the aristocracy and gentry,” writes McNeil, “but included men of the artisan, artist, and upper servant classes, who wore versions of this visually lavish clothing with a distinctive cut and shorter jackets. Wealthier shopkeepers and entrepreneurs also sometimes wore such lavish clothing, particularly those associated with the luxury trades, such as mercers and upholsterers -” (p14)

It was possible to copy certain aspects of macaroni fashion on a cheeper budget. The hairstyle in particular was achievable without braking the bank. And there were ways to replicate the effects of certain expensive fashion trends for cheeper prices. For example patterns could be printed rather than embroidered.

[Left: printed waistcoat, cotton, c. 1770–90, via The Met, number: 35.142.

Right: embroidered waistcoat, silk, c. 1780–89, via The Met, number: 2009.300.2908.]

The Town and Country Magazine complains “we now have Macaronies of every denomination, from the colonel of the Train’s-Bands down to the errand-boy.” (McNeil, p169) The Morining Post mocks macaronies that couldn't financially keep up with the trends:

The macaronies of a certain class are under peculiar circumstances of distress, occasioned by the fashion, now so prevalent, of wearing enormous shoe-buckles; and we are well assured that the manufactory of plated ware was never known to be in so flourishing a situation.

(14 Jan, 1777)

In 18th century England, class was about more than just how much money you had. It was about pedigree. “English society was particularly alert to those whom it felt were using clothes to achieve a social status they did not merit” explains McNeil. Richard Cosway was a famous macaroni from modest background. Born to a Devonshire headmaster he was sent to London to study painting at 12. He became a very successful miniature painter and grew rich from the patronage of the Prince of Wales (later George IV) and Whig circles. In Nollekens and his Times J.T. Smith writes of Cosway:

He rose from one of the dirtiest boys, to one of the smartest of men. Indeed so ridiculously foppish did he become that Mat Darly, the famous caricature print-seller, introduced an etching of him in his window in the Strand, as ‘The Macaroni Miniature Painter’

(McNeil, p105-14)

But it was not only the Darlys that satirised Cosway Hannah Humphrey mocks Cosway as a social climber in A Smuggling Machine or a Convenient Cos(au)way for a Man in Miniature which depicts him standing under the petticoats of his much taller wife Maria. In the background there is a picture of Cosway climbing a ladder that rests upon a woman (she is believed to either be Angelica Kauffman or the Duchess of Devonshire). Below this reads:

Lowliness is Young Ambitions Ladder,

Whereto the climber upward turns his Face

But when he once attains the upmost round

He then unto the Ladder turns his back,

Looks unto the clouds - scornin [sic] the base degrees

By which he did assend.

Shak. Jul. Caesar.

[A Smuggling Machine or a Convenient Cos(au)way for a Man in Miniature, print, c. 1782, by Hannah Humphrey, via The British Museum.]

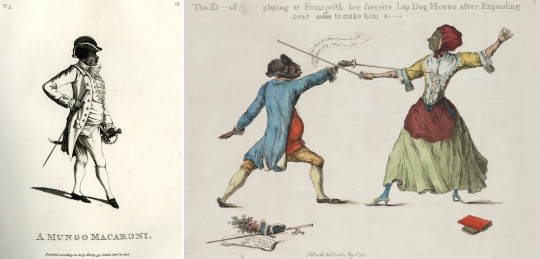

Another famous macaroni not born into the aristocracy was Julius Soubise. Brought to England from the West Indies as a slave he was taken in by Catherine Hyde, the Duchess of Queensbury. She gave him a leisured childhood, in which he was taught to play and compose for the violin, was taught to fence by Domenico Angelo, and learned oration from David Garrick. “Macaroni caricatures of Soubise parodied a foppish upstart whose outfits and entertainments, financed by the Duchess, affronted both racial and social expectations of an African male.” Writes Petter McNeil, Soubise was satirised as “a Mungo Macaroni” an “offensive term meaning a rude or forward black man.” (p118)

[Left: A Mungo Macaroni, print, c. 1772, by Matthew Darly, via The British Museum.

Right: The D------ of [...]-- playing at foils with her favorite lap dog Mungo after expending near £10000 to make him a----------*, print, c. 1773, by William Austin, via Yale Center for British Art.]

The expense of Stede’s wardrobe is a key part of the narrative. Stede has nice fancy luxurious things. Ed wants nice fancy luxurious things. Ed was born a poor brown boy and while he may be rich now he can never truly change his class. He could be as rich as Richard Cosway or Julius Soubise but to the gentry he will always be that poor brown boy.

Gender

As we have already seen in the tirade against men using umbrellas the macaroni was perceived as being of “the doubtful gender”. (The Morning Chronicle, 4 Oct, 1784)

The Natural History of a Macaroni writes that there “has within these few years past arrived from France and Italy a very strange animal, of the doubtful gender, in shape somewhat between a man and monkey,” that dresses “neither in the habit of a man or woman, but peculiar to itself”. The author states that “they are in no respect useful in this country”:

that the minister of the war department would give orders to have them enlisted for the service of America: we do not mean to put them on actual duty there. Alas! they are as harmless in the field, as they are in the chamber, but they may stand as faggots to cover the loss of real men.

(Walker’s Hibernian Magazine, July 1777, p458-9)

A “faggot” being “A man who is temporarily hired as a dummy soldier to make up the required number at a muster of troops, or on the roll of a company or regiment.” (see OED)

[The Masculine Gender & The Feminine Gender, etching with touches of watercolour, c. 1787, Attributed to Henry Kingsbury, via The Met.]

The macaroni wasn’t just considered effeminate because of the way they dressed but also because of their interests and the way walked and talked. Famous for playing fops and macaroni, the actor David Garrick did a lot to establish the character of the macaroni in the public mind. In his poem The Fribbleriad Garrick mocks the men who were offended by his performances asserting, perhaps accurately, that they were offended because it was them he mocked. He portrays a group of angry effeminate men meeting in order to seek revenge on him for his portrayal of them:

May we no more such misery know!

Since Garrick made OUR SEX a shew;

And gave us up to such rude laughter,

That few, ’twas said, could hold their water:

For He, that player, so mock’d our motions,

Our dress, amusements, fancies, notions,

So lisp’d our words, and minc’d our steps,

The macaroni had become more than simply an effeminate man, he had become a new sex. Something not quite man or woman. Something in-between. A new description of a macaroni asks the question:

Is it a man? ‘Tis hard to say - A woman then

- A moment pray -

So doubtful is the thing, that no man

Can say if ‘tis a man or woman:

Unknown as yet by sex or feature,

It moves - a mere amphibious creature.

(McNeil p169)

Sexuality

Much like today in the 18th century effeminacy was associated with homosexuality. Men who had sex with other men were known as mollies. A Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue (1785), defined a molly as “A Miss Molly; an effeminate fellow, a sodomite”. In the History of the London Clubs (1709), Ned Ward characterises mollies as follows:

There are a particular Gang of Wretches in Town, who call themselves Mollies, & are so far degenerated from all Masculine Deportment or Manly exercises that they rather fancy themselves Women, imitating all the little Vanities that Custom has reconcil’d to the Female sex, affecting to speak, walk, tattle, curtsy, cry, scold, & mimick all manner of Effeminacy.

“By the 1760′s,” explains Peter McNeil, “too much attention to fashion on the part of a man was read as evidence if a lack of interest in women”. (p152)

Macaroni were often portrayed as incapable or simply uninterested in sexual relations with women. This attitude is expressed by Mr. Bate in the following dialogue from The Vauxhall Affray; Or, the Macaronies Defeated:

Mr. Fitz-Gerall: I always though a fine woman was only made to be looked at.

Mr. Bate: Just sentiments of a macaroni. You judge of the fair sex as you do your own doubtful gender, which aims only to be looked at and admired.

Mr. Fitz-Gerall: I have as great a love for a fine woman as any man.

Mr. Bate: Psha! Lepus tute es et pulpamentum quæris?

Mr. Fitz-Gerall: What do you say, Parson?

Mr. Bate: I cry you mercy, Sir, I am talking Heathen Greek to you; in plain English I say, A macaroni you, and love a woman?

Mr. Fitz-Gerall: I love the ladies, for the ladies love me.

Mr Bate: Yes, as their panteen, their play-thing, their harmless bauble, to treat as you do them, merely to look at

While lack on interest in woman does not necessarily mean attraction to men, Matthew Darly takes the implication there in his 1771 set of macaroni caricatures which induces a print entitled Ganymede, a reference to Zeus’ male lover of the same name. Ganymede is believed to be a parody of Samuel Drybutter who had been arrested for attempted sodomy in January 1770. Darly also includes the character Ganymede in Ganymede & Jack-Catch. Jack-Catch is a reference to the infamous English executioner John Ketch. In the print Jack-Catch says, “Dammee Sammy you’r a sweat pretty creature & I long to have you at the end of my String.” Ganymede replies, “You don’t love me Jacky”. Jack-Catch is holding a noose with one hand and stroking Ganymede’s chin with the other. Jack-Catch is soberly dressed in typical 18th century menswear, while Ganymede’s dress is distinguished by his lace ruffles and styled wig. The print is not only suggesting that macaroni are sodomites but making a joke of the execution of them. The punishment for a sodomy at this time in England being death by hanging.

[Left: Ganymede, print, c. 1771, Matthew Darly, via The Met.

Right: Ganymede & Jack Catch, print, c. 1771, Matthew Darly, via The British Museum]

An anonymous letter to the Public Ledger (5 Aug, 1772) says blatantly what others had already implied. “The country is over-run with Catamites, with monsters of Captain Jones’s taste, or, to speak in a language witch all may understand, with MACCARONIES”. The writer warns macaroni who have “escaped detection” as sodomites and “therefore cannot fairly be charged” that they have not avoided suspicion:

Suspicion is got abroad-the carriage-the deportment-the dress-the effeminate squeak of the voice-the familiar loll upon each others shoulders-the gripe of the hand-the grinning in each others faces, to shew the whiteness of the teeth-in short, the manner altogether, and the figure so different from that of Manhood, these things conspire to create suspicion; Suspicion gives birth to watchful observation; and, from a strict observance of the Maccaroni Tribe, we very naturally conclude that to them we are indebted for the frequency of a crime which Modesty forbids me to name. Take warning, therefore, ye smirking group of Tiddy-dols: However secret you may be in your amours, yet in the end you cannot escape detection;

Bows on His Shoes

18th century shoes were typically buckled, laces and ribbons were simply unfashionable. As mentioned previously macaroni were distinguished by the size and decoration of the buckles. So are Stede’s bows simply ahistorical? Well there are references to 18th century men wearing laces and ribbons.

Towards the end of the 18th century laces started to come into fashion. Appeal from the Buckle Trade of London and Westminster, to the Royal Conductors of Fashion (1792) complained that despite how “tender and effeminate the appearance of Shoe Strings” the “custom of wearing them has prevailed.”

Perhaps the most intriguing reference is that of Commissioner Pierre Louis Foucault’s papers where he details the surveillance, investigation and entrapment of "pederasts” in Paris. It is important to note that the word “pederasty” was used synonymously with “sodomy” in the 18th century and did not denote age simply sex. An Universal Etymological English Dictionary (1726) defines “A pederast” as “a Buggerer” and “Pederasty” as “Buggery”.

Foucault and the men working with him identified particular clothing worn by men seeking sex with other men that he called the “pederastical uniform”. In Foucault’s papers men are described as being “attired in such a way as to be recognized by everyone as a pederast”, “clothed with all the distinctive marks of pederasty”, or simply “dressed like a pederast”. This “uniform” generally included “some combination of frock coat, large tie, round hat, small chignon, and bows on the shoes.” Jeffrey Merrick in his article on Foucault speculates that these men dressed this way to signal to each other. However when questioned by police they would understandably deny such a purpose, one man when questioned about his outfit responded that everyone “dresses as he sees fit”. (Jeffrey Merrick, Commissioner Foucault, Inspector Noël, and the “Pederasts” of Paris,1780-3)

Conclusion

I’m not saying Stede is intended to be a macaroni. If that were the case they would have given him the iconic macaroni hairstyle. However the costuming team has clearly pulled from fashion trends that were associated with effeminacy and homosexuality. While OFMD is evidently wholly unconcerned with creating period accurate costumes the costumes are still clearly inspired by historical fashions. Perhaps the curtains really are just blue but maybe Stede wears bows on his shoes because he’s gay.

#I had way too much fun doing this#our flag means death#ofmd meta#stede bonnet#queer history#macaroni#historical fiction#fashion history

195 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Jay, Green Woodpecker, Pigeons and Redstart, c.1650

by Francis Barlow

Oil on canvas

Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, USA

#Francis Barlow#fineart#art#painting#artwork#masterpiece#fineartprint#gallery#museum#woodpecker#specht

242 notes

·

View notes

Text

TOM HAMMICK (b 1963, British)

Artist Tom Hammick has described landscape in his work as a metaphor to explore an “imaginary and mythological dreamscape.” Drawing from a wide range of sources, from Japanese woodblock prints to Northern European Romantic painting and contemporary cinema, Hammick’s depictions of isolated human dwellings grounded in uncanny dream-like settings summon the uneasy atmosphere of a psychologically-charged thriller, or a dystopian suburban nightmare.

Hammick was the recipient of the V&A Prize at the International Print Biennale, Newcastle, UK in 2016.. His work is in many major public and corporate collections including the British Museum, the Victoria and Albert Museum, Bibliotheque Nationale de France, Deutsche Bank, the Yale Center for British Art, and The Library of Congress, Washington DC.

hammick.com/

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

It is easy to think of discipline as a code of behaviour imposed by external authority and maintained by force, as it often is. Discipline of this sort existed in the Navy in the eighteenth century only in a limited and subsidiary form, riding on the back of the real, natural discipline of the Service. This was something inherent in the nature of seafaring, and common to ships and seamen everywhere. It owed almost nothing to the authority of officers, and almost everything to the collective understanding of seamen. A ship at sea under sail depended utterly on disciplined teamwork, and any seaman knew without thinking that at sea orders had to be obeyed for the safety of all. This was not a matter of unquestioning obedience—those working aloft in particular had to exercise a great deal of initiative—but of intelligent co-operation in survival.

— Nicholas A.M. Rodger, The Wooden World: An Anatomy of the Georgian Navy

Charles Brooking, 1723–1759, British, English Ships Running before a Gale, before 1759, Oil on canvas, Yale Center for British Art.

#age of sail#sailors#the sea#naval history#maritime art#charles brooking#nicholas a m rodger#the wooden world#royal navy#maritime history#intelligent co-operation in survival

41 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Mt St. Gothard von Charles Yardley Turner

Radierung Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, USA

#Charles Yardley Turner#landschaft#landschaftsmalerei#kunst#gemälde#meisterwerk#kunstdruck#museum#galerie#kunstwerk#alte meister#turner#yale#british art#art#artwork#cliffs#mountains#sepia

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Book Recommendations: Dark Academia

Long Black Veil by Jennifer Finney Boylan

Long Black Veil is the story of Judith Carrigan, whose past is dredged up when the body of her college friend Wailer is discovered 20 years after her disappearance in Philadelphia’s notorious and abandoned Eastern State Penitentiary. Judith is the only witness who can testify to the innocence of her friend Casey, who had married Wailer only days before her death.

The only problem is that on that fateful night at the prison, Judith was a very different person from the woman she is today. In order to defend her old friend and uncover the truth of Wailer’s death, Judith must confront long-held and hard-won secrets that could cause her to lose the idyllic life she’s built for herself and her family.

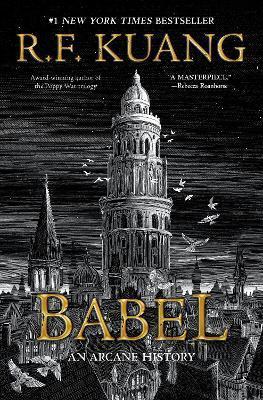

Babel by R.F. Kuang

Traduttore, traditore: An act of translation is always an act of betrayal.

1828. Robin Swift, orphaned by cholera in Canton, is brought to London by the mysterious Professor Lovell. There, he trains for years in Latin, Ancient Greek, and Chinese, all in preparation for the day he'll enroll in Oxford University's prestigious Royal Institute of Translation - also known as Babel.

Babel is the world's center of translation and, more importantly, of silver-working: the art of manifesting the meaning lost in translation through enchanted silver bars, to magical effect. Silver-working has made the British Empire unparalleled in power, and Babel's research in foreign languages serves the Empire's quest to colonize everything it encounters.

Oxford, the city of dreaming spires, is a fairytale for Robin; a utopia dedicated to the pursuit of knowledge. But knowledge serves power, and for Robin, a Chinese boy raised in Britain, serving Babel inevitably means betraying his motherland. As his studies progress Robin finds himself caught between Babel and the shadowy Hermes Society, an organization dedicated to sabotaging the silver-working that supports imperial expansion. When Britain pursues an unjust war with China over silver and opium, Robin must decide: Can powerful institutions be changed from within, or does revolution always require violence? What is he willing to sacrifice to bring Babel down?

Babel - a thematic response to The Secret History and a tonal response to Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell - grapples with student revolutions, colonial resistance, and the use of translation as a tool of empire.

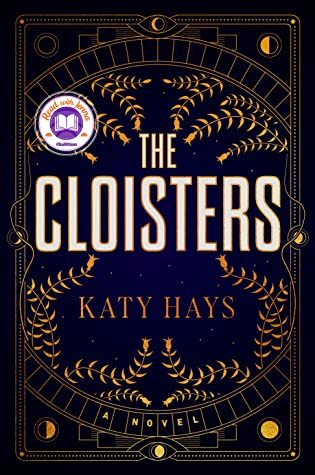

The Cloisters by Kathy Hays

When Ann Stilwell arrives in New York City, she expects to spend her summer working as a curatorial associate at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Instead, she finds herself assigned to The Cloisters, a gothic museum and garden renowned for its medieval art collection and its group of enigmatic researchers studying the history of divination.

Desperate to escape her painful past, Ann is happy to indulge the researchers’ more outlandish theories about the history of fortune telling. But what begins as academic curiosity quickly turns into obsession when Ann discovers a hidden 15th-century deck of tarot cards that might hold the key to predicting the future. When the dangerous game of power, seduction, and ambition at The Cloisters turns deadly, Ann becomes locked in a race for answers as the line between the arcane and the modern blurs.

A haunting and magical blend of genres, The Cloisters is a gripping debut that will keep you on the edge of your seat.

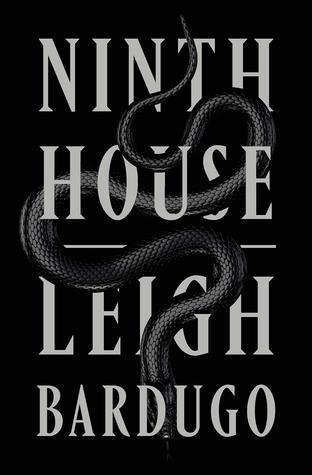

Ninth House by Leigh Bardugo

Galaxy “Alex” Stern is the most unlikely member of Yale’s freshman class. Raised in the Los Angeles hinterlands by a hippie mom, Alex dropped out of school early and into a world of shady drug dealer boyfriends, dead-end jobs, and much, much worse. By age twenty, in fact, she is the sole survivor of a horrific, unsolved multiple homicide. Some might say she’s thrown her life away. But at her hospital bed, Alex is offered a second chance: to attend one of the world’s most elite universities on a full ride. What’s the catch, and why her?

Still searching for answers to this herself, Alex arrives in New Haven tasked by her mysterious benefactors with monitoring the activities of Yale’s secret societies. These eight windowless “tombs” are well-known to be haunts of the future rich and powerful, from high-ranking politicos to Wall Street and Hollywood’s biggest players. But their occult activities are revealed to be more sinister and more extraordinary than any paranoid imagination might conceive.

This is the first volume in the “Alex Stern” series. A highly anticipated sequel, Hell Bent, is expected early next year.

#dark acamedia#fiction#thriller#fantasy#dark fantasy#library books#reading recommendations#reading recs#book recommendations#book recs#booklr#book tumblr#to read#TBR pile#tbr#library blog#book blog

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

Benedetto Gennari (IT, 1633 - 1715)

Cleopatra, 1674–75. Oil on canvas: 124 x 105 cm. Collection Yale Center for British Art

Cleopatra’s body was found alongside two of her maids

Some scholars suggest that it was Octavian who sent his guards to murder Cleopatra after he killed her son Caesarion, allowing him to take control over the empire.

Christoph Schaefer, a German historian and professor at the University of Trier, “ancient papyri show that the Egyptians knew about poisons, and one papyrus says Cleopatra actually tested them,” suggested that Cleopatra died from a drug cocktail made of opium, aconitum (wolfsbane) and hemlock and not a snake bite.

Historians continue to debate the circumstances around Cleopatra’s death, but it remains shrouded in uncertainty. With only anecdotal accounts surviving about her final hours it appears that we may never know the truth.

The Enigma of Cleopatra's Death: Was it Suicide or Murder?

s: https://www.ancient-origins.net/history-important-events/cleopatras-death-002117

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Benedetto_Gennari_-Cleopatra-_Google_Art_Project.jpg

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Eighteenth-Century Studies Syllabus Treasury

Caption: Thomas Rowlandson, 1756–1827, British, The Exhibition Stare-Case, Somerset House, ca. 1800, Watercolour and pen and ink on medium, slightly textured, cream wove paper, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B1981.25.2893. Public Domain.

Today, I uploaded a new syllabus to the ECF journal online Syllabus Treasury:

ENGL3623, "The Eighteenth Century: Scandal and Sociability," Dr. Nicola Parsons, The University of Sydney

Email your syllabus for inclusion to: [email protected].

What we do!

#eighteenth-century fiction#18th-century art#18th-century literature#1700s#eighteenth century#18th century

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi, I love your blog! I was wondering, and I only thought of it because of your username and of her melancholic aria, if you knew of any paintings or illustrations related to Purcell's "When I Am Laid In Earth" or even just Dido's death in general? Thank you!😊

I'm so glad that you like my blog! I love Purcell's Dido and Aeneas (it was one of the inspirations for my url). I get "When I Am Laid in Earth" stuck in my head often, but it's too high for me to sing, sadly...

I don't have any specific recommendations for illustrations of Purcell's opera, but I do have some favorite depictions of Dido's death, which are mostly inspired by Vergil’s account in the Aeneid:

My favorite paintings are probably Henry Fuseli's Dido in the collection of the Yale Center for British Art (I like the inclusion of Iris cutting Dido's hair to release her soul) and Giambattista Tiepolo's Death of Dido in the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts (this one is actually the header on my blog). I also like Joshua Reynolds' Death of Dido, which is in the British Royal Collection, and a work in the Getty Museum that is attributed to Rubens' workshop.

Additionally, my favorite print is an etching by Stefano della Bella after Parmigiano of Dido Killing Herself, which, like the Rubens workshop painting, shows Dido with Aeneas' sword in the moment before the suicide.

I hope that you enjoy some of these works too! As a bonus, my favorite depiction of Dido before her death is Joseph Mallord William Turner's Dido Building Carthage. Jean-Bernard Restout's series of oil sketches for a tapestry design are also good, if not as complete as a finished painting: Dido Sacrificing to Juno in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, three works of Dido and Aeneas in the LACMA collection, and The Death of Dido, which was up for auction by Sotheby’s in 2019.

#dido dicit#ask#answer#oh-come-sweet-death#Thanks for giving me an excuse to look through my old posts!#I really should repost some of these paintings since image quality has improved so much since I started this blog...#Dido#Dido and Aeneas#death of Dido#suicide of Dido#Aeneid#mythology#Henry Fuseli#Giambattista Tiepolo#Joshua Reynolds#Stefano della Bella#Parmigiano#Joseph Mallord William Turner#Jean-Bernard Restout

23 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Back to the 1760s, the height of engageantes (from top to bottom) -

ca. 1762 Lady in a Pink Silk Dress by Allan Ramsay (Yale Center for British Art, Yale University - New Haven, Connecticut, USA). From artuk.org 998X1200.

ca. 1762 Woman in Blue (previously known as 'Miss Edgar') by Thomas Gainsborough (Ipswich Borough Council Collection, specific location ? - Ipswich, Suffolk, UK). From artuk.org 1542X1928.

1765-1770 Sophie Charlotte von Haus née von Bennigsen by Johann Georg Ziesenis (Saarland Museum - Saarbrücken, Saarland, Germany). From tumblr.com/lenkaastrelenkaa 732X958.

Lady by Giuseppe Baldrighi (location ?). From tumblr.com/lenkaastrelenkaa; fixed spots w Pshop 1195X1388.

Rosalie Levasseur by Louis Michel van Loo (location ?). From the lost gallery's photostream on flickr; blurred background & fixed spots elsewhere w Pshop 1564X1928.

1769 Madame Francois Buron by Jacques-Louis David (location ?). From tumblr.com/catherinedefrance; fixed cracks & some spots w Pshop 843X1022.

#1760s fashion#Louis XV fashion#Georgian fashion#Rococo fashion#Allan Ramsay#lace cap#lace choker#fichu#Thomas Gainsborough#sacque back#straight hair#lace engageantes#Johann Georg Ziesenis#lace stomacher#lace mantle#Giuseppe Baldrighi#Louis Michel van Loo#high coiffure#hair jewelry#Jacques-Louis David

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Meynnart Wewyck’s workshop-part 1-proven paintings

Meynnart Wewyck has for long been hidden in shadow of Hans Holbein the Younger. Everybody knows Holbein’s work, but very few of us know of Meynnart’s work. Even though he was working for Tudors in between 1502-1525. For 23 years! Holbein only for 11 years had royal patronage.

So how come we only have 6 confirmed portraits by Meynnart Wewyck?

It’s complicated. Because most likely Wewyck didn’t work alone. He probably was a master overlooking workshop of artists(painters)-yet only he would be on royal records as the one who would be paid. Work of same workshop can be difficult to identify as painters could come and go(or be sick when certain stage of painting needed to be finished) the resulting work from same workshop could be very different. Their skillset varied, the brushstrokes varried. Depending on turnover of painters-this can be nightmare to try to identify.

Even with all the perks of modern technology. And in case of Meynnart Wewyck’s work, it might be even more complicated. Because yes, dendrology(testing of the wood to determine painting’s age) is helpful, but might not be a deal-breaker when it comes to workshops. Which will sound crazy at first, as you’ll read this, so read entire thing.

Currently I know of 6 paintings which are identified as Meynnart’s work-and experts have no doubt about it.

1.Posthumous portrait of Lady Margaret Beaufort, comissioned in c.1510,

180 x 122 cm , location: the Master's Lodge, St John’s College, Cambridge, UK

2.Portrait of Henry VII, 38 x24.5 cm, location: Society of Antiquaries of London: Burlighton House, UK

3.Portrait of Henry VIII, location: Denver Art Museum, USA, supposedly ca. 1509

4.Portrait of Henry VIII, 44,5 x 29,8 cm location: Anglesey Abbey(National Trust Collection), UK. Supposedly ca 1515 - 1520

5.Portrait of Henry VIII, location: Private collection, supposedly ca 1519

6. Portrait of Henry VIII, location: Private collection, supposedly ca 1513

Why did I put number 4 there twice and crossed one? Because the Henry VIII we look at is not the original. There is painting beneath(which I presume to be Henry too):

How could they then possibly know this one is by same artists? Well, the cloth of gold has same pattern as in 5 and 6-but imo they didn’t come to that conclusion based upon painting we can see. But due to exhamining all of the painting, not just visual exterior.

Bit of background on the research done by professionals, which I aplaud:

Before 2019, no painting was 100% identified as by Meynnart. Then research into lady Margaret’s painting(1) has been proven to be an original work by Wewyck. They also found evidence that it belonged to John Fisher, Bishop of Rochester and probably never was in hands of Henry VIII.

(So presumably he had some other painting of her, perhaps the 1506 one.)

We can contribute this confirmation to art historians Dr Charlotte Bolland of the National Gallery, London and Dr Andrew Chen of St John's College, Cambridge.

They published their research in the April 2019 issue of Burlighton Magazine. Based on their work with the portrait of Lady Margaret Beaufort, they also attributed a stylistically and structurally similar portrait of one portrait of Henry VII(2) to Wewyck.

Based upon identifying this one, very quicky, still in 2019, a group of specialists from the Yale Center for British Art, with support from the National Portrait Gallery, London and the Hamilton Kerr Institute Cambridge, initiated a research project at the Denvert Art Museum. (Lots of different institutions doing combined research.)

They found 5 paintings painted on wood from same tree. Henry VII(2) and 4 portraits of Henry VIII (3,4,5,6) were painted on that wood.

And according to some sources also they laso identified 2 portraits of Elizabeth of York. While they studied it, and it was part of their project. But ‘being fairly certain’ they are tributable to Wewyck’ is not same as being certain.

What is madening to me, is that I went to websites of all those institutions, searched on interenet for weeks-and yet I cannot find any detailed report about this 2nd project! I have no real idea what they found! I give up. I can’t find it.

Just know only few tidbits about number 4 and then I found out on Denvert Art Museum short article-which deals with few more tidbits. But that is it. And it irritates me to no end that I don’t have more about this!

I’d really love to know what the actual findings were.

It took me ages to even find out which paintings they meant(those in private collections-those were the problem). After going through several articles and ending up empty handed each time(about those in private collection), eventually I found them on this webpage:

https://web.archive.org/web/20200603202704/http://damscout.squarespace.com/comparisons The link for it was actually on wikipedia the whole time!

And I know they found way more. I know it. There are at least 6 different methods they use! Here they are:

DENDROCHRONOLOGY & PANEL EXAMINATION

Deals with exhamining the wood of frame or wooden pannel painting is painted upon. Not all paintings are done on wooden pannels, some are on canvases only, and you can only hope the frame is original.

PIGMENT AND MEDIA ANALYSIS

This is very important because certain painters could always use same pigment mixture or varnish mixture, or glue etc. Or pigments in painting have changed colour, and you need to prove it.

MICROSCOPIC EXAMINATION

This is crucial in order to know artist technique and to determine if it is by same hand. Very HD image can be also be used for it(I use them as amateur). It’s especially great to use if you have two paintings and wish to compare how the painter did the details.

The other 3 methods all deal with allowing us to see beneath the layers of the paint. Like different filters:

INFRA-RED REFLECTOGRAPHY

Particularly good to see the original sketches/drawing-which is likely to be done from life. (and hence to realise if painting wasn’t altered)

X-RAY EXAMINATION

Tbh, I don’t really understand in what way it is different from Infra-red, other that than you can see different layer. It just reveals some details better.

ULTRA VIOLET EXAMINATION

Another method to see what we can’t with naked eye. This one I know what it is for-it reveals overpaint on the painting. Even minor retouching can be seen with this.

Denvert Art Museum on September 1st 2019, posted a short article and it, it credits the people, who did this expert analysis:

Ian Tyers, dendrochronologist, who undertook the dendro on the five linked portraits;

Pam Skiles, senior paintings conservator at the DAM, who facilitated the examination and did the initial infrared examination;

Natalie Feinberg Lopez, architectural conservator, who was contracted in to do the XRF analysis;

Kathleen Stuart, former Berger Collection curator,

and then the author of the article: Christine Slottved Kimbriel, Paintings conservator (of Cambridge University’s Hamilton Kerr Institute in the United Kingdom).

She mentions in the article exhamining the picture under the microscope, analyzying the paint using a technique called x-ray fluorescence spectroscopy and taking tiny paint samples for chemical analysis back in the lab in Cambridge.

And also, working together with an imaging specialist using infrared reflectography to reveal images of what lay beneath the top paint layer.

All methods are nice, but here is what they found. Denvert Art Museum’s portrait of Henry VIII originally had blue background. And it wasn’t only painting in that project, where blue background was revealed. 3/4 had it. Which? Idk. They exhamined 1 of Henry VII and 3 of Henry VIII in Denvert Art Museum. I can only be sure of number 3. Out of 5 paintings, 1 had blue background, 4 had green-and of those 3 turned out to be originally blue.

Furthermore they found traces of gold and paint frame of number 3, which made them believe originally its frame and edge was once decorated as number 2 was:

with golden motive above above the sitter, and red trim and green-and-white striped “barber’s pole” trim:

But back to dendrology. So, numbers 2-6 are all done on wooden pannels cut from same tree. 5 paintings painted on wood of same baltic oak, which was felled between 1500-1515. Which gives us date cca 1500-1520, when these were used-according to proffesionals.

(It is presumed that is when they should be used. Imo it should be stretched to 1500-1525 at least.)

Lady Margaret’s posthumous portrait is made out of wood of two baltic oaks(different ones than the remaining 5 paintings), and testing shows one oak was felled after c.1487 and the other after c.1489. So timeframe for these two oaks to be cut and used is ca 1490-1510.

So it is possible that oak was cut 10 or even 20 years before it was used.

Why would they wait so long before using it? Excellent question.

I believe I might know the answer. I heard of practise certain monasteries allegedly did. They would leave cut tree trunks intended to be used for roofs in forest for several years. If nothing touched them(no bug started to eat it, etc.) until certain time was over, then they’d use the wood. Because then it was way less likely that any woodworm would attack the wood later on. Hence insuring the quality. Such wood would last.

If the painters also prefered older untouched wood, it’d explain it. They’d buy one such tree trunk(or part of it) from reliable source and then use it all, over course of many years.

So the dendrology analysis is helpful, in letting us know the paintings are early 16th century works and very likely same workshop, but there is a big issue.

Except lady Margaret’s portrait-where we know portrait’s history, we cannot be sure if the painting is original or very early copy.

Even knowing that some portraits originally had blue background(number 6 still does), and green damask background is alteration in some of them-the traces of blue found, are not conclusive proof that it is an original painting from life.

Because we have portrait of clearly young adult Henry VIII(number 6) with this blue background-suggesting it was still popular at least in 1st half of 1510s.

(Then in mid 1510s in my opinion green damask background took on and continued to be popular up to late 1520s(for half-lenght portraits, miniatures from mid 1520s have ultramarine blue backgrounds).)

If for example young King Henry decided in 1510 to have posthumous portrait of his father made(and we know Henry VIII loved to have posthumous portraits of his relatives), it’d still have the blue background. Dendrology would still fit, the artist/workshop would be the same. If this is the case-how on earth as an expert do you determine if it is an original? I don’t see how. Unless there is some alteration in costume or if you have some proof that artist(s) in this timeframe did something differently.

But for that you’d need to identify a more of paintings by this workshop.

But we’re long way from that still. But we know Wewyck’s workshop certainly made more paintings, that is clear from records. He appears in them as Dutchman, Flemish or Netherlandish-a region known for its artists.

There was no universal spelling back then, so there is at least 15 different ways his name was spelled like, and in Scottland he was even refered to as an English painter called Mynour, instead of a painter in service of English King.

Scotland is actually where he starts in records. In September 1502, Meynnart Wewyck delivered 4 paintings to King James IV of Scotland.

Those paintings were of King Henry VII, Queen Elizabeth of York, Princess Margaret(James’ bethrohed) and Prince Harry(future Henry VIII).

Why no prince Arthur? Because he died in April that year.

Why no princess Mary(Future Queen of France)? Because she was child of 6 and of no importance to Scottish King, unlike Margaret or young Harry.

So prior to September 1502, Wewyck was already in service of English royals.

He then appears to have stayed in Scotland up to November 1503.

Records show he made portraits of James and his bride in 1503.

He might have also done portrait of James IV located in Abbotsford House in Scotland(it is atributed to him, but as far as I know it is not confirmed), dated as 1502: (although on painting it looks more like 1507-but that might be alterated date, or added date)

It is also suggested that portrait of James IV in inventary of Henry VIII was also made by Wewyck in between 1502-1503. But few portraits of James survive and we have mostly just drawings or engravings of them.

Do we have any clue how those lost Scottish paintings looked like? Maybe.

It’s likely that sketch of Margaret Tudor in Receuil d'Arras, a collection of portraits copied by Jacques de Boucq, done cca 1570, is based upon one of the two paintings of Margaret by Meynnart Wewyck:

(And yes, this commonly mislabelled as drawn from life)

The same collection of drawings also consist sketch of James IV(on left) and of his son Alexander Steward(on right)- Both could have been done by Wewyck. If those are who the text beneath drawing says they are.

Later, in March 1505 Henry VII paid Mennart Wewyck £1 for pictures(paintings).

(we don’t know which, if it was for past work or for future work. For example painter Sittow was not paid for works commissioned by Queen Isabella of Castile many years after she died.)

Wewyck also made 2 portraits of lady Margaret Beaufort.

1st was comissioned in 1506-presumably from life, 2nd posthumous was comissioned around 1510(that is our number 1).

He also made drawings/sketches then used by sculptor Pietro Torrigiano who made lady Margaret’s tomb.

But even though he was on royal payroll still in 1525(then he presumably died), as far as I know, we don’t know about which other paintings he made in between 1510-1525.

(Perhaps somebody can recommend a source which would give us a clue.)

Let’s look at his proven work again:

1)Posthumous portrait of Lady Margaret Beaufort, the Master's Lodge, St John’s College, Cambridge(UK):

It’s huge! (no wonder it was refered to as a table) And sadly the painting doesn’t look exactly as it used to when it was made. It suffered localised paint loss, particularly in the lower-left corner, and is also partly obscured by discoloured varnish and retouchings. Further more, the face when being made was bit off, and painter moved it about an inch(this happens a lot, sometimes you sketch it all-come to get snack and return and realise it is iffy!) Normally, you’d not see that painter did this. But sadly, due to thinning of layers you can. You see lady Margaret’s nose twice.

So if you wish to know how originally those parts of painting looked like, I recommend looking at a copy by Rowland Lockey, commissioned in 1598 (it’s also in St. John’s Colledge, University of Cambridge):

it’s really great copy(unlike so many copies of Tudor paintings)

2)Portrait of Henry VII in Society of Antiquaries of London:Burlighton House(UK):

3)Portrait of Henry VIII, Denver Art Museum(USA):

4)Potrait of Henry VIII Anglesey Abbey(National Trust Collection), (UK):

Once again, this is actually not the original portrait. Beneath the layers of the paint is another portrait of Henry VIII(or at least it seems like him to me)

Sadly I am still searching for bigger picture which would show the painting beneath it.

5)Portrait of Henry VIII , Private collection:

6)Portrait of Henry VIII, Private collection:

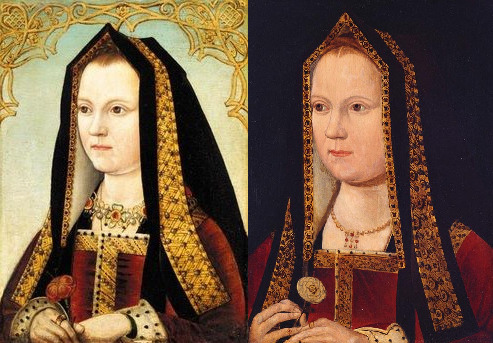

As for Elizabeth of York, they were looking at these two portraits of her:

Queen Elizabeth of York, about 1470–98. Royal Collection Trust, Haunted Gallery, Hampton Court Palace( UK):

38.7 cm x 27.8 cm

Queen Elizabeth of York, about 1500(supposedly). Bryan Collection, Crab Tree(supposedly- I couldn’t find it):

And imo they are not drawn from life. But are very early copies. Very early indeed. Maybe even 1510s or 1520s. Because they have turned frontlets-just as on her tomb. Due to fabric upon hood being black(only paste is white), this details is so hard to spot-that it is unlikely it could have been copied when artist no longer knew how it was supposed to look like.

But what exactly made them believe in first place that these might be by same artist/same workshop? The artistic similiarities-are kind of vague term. Sadly, I couldn’t find what exactly they mean. It’s not written down in April 2019 article, and as I said nor could I find detailed report about the fallowing research. Just tidbits

However, if you just look at those paintings in HD(or at good photos), even as amateur you can spot some the similiarities. So which are they? Imo:

1)the fur

number 2(on left) and number (3)-shading of it suggests same hand

Problem is, different kinds of fur would require different shading and hence it could be hard to spot.

2)the cloth of gold pattern. You might think King could have cloth of with this pattern-and be painted by several different artists-and they’ve still end up same. Not entirely true.

Idk if you ever attended drawing lessons. I have and one of the exercises we were to do-was to draw picture of certain actor based upon his photography. And each person’s same actor-came out completely different.

Of course trained painter, with good eye, might be able to do very good copy, and few even copy as good as the original. But usually that is not the case.

Each person does it bit differently even if they try not to. So it should be recognizeable feature. But it is isn’t in many cases-because they weren’t just painting the area. In most cases these painting were gilded. And sometimes re-gilded later on.

And way too often the re-gilding was done poorly, destroying the original pattern beneath and skill of previous artists hence doesn’t show. Details are often gilded over!

I am 90% sure that brooch(above) on Henry VII’s hat on number 2 is same as on multiple painting(including number 6), all of which have it with red stone:

On Henry VIII, which grew to bigger than his father, it looks tiny! But it’s very likely same brooch.

Also, rather often silver or golden gilding comes off(that is why so often it gets re-gilded), revealing just the basic under layer made in beige or yellowish colour.

And only traces of gold(which in same cases disappeared completely) are later found during proffesional exhaminations.

Why not every painting has issues like that? Due to different conditions painting is kept in=(enviroment vs glue), and due to different people taking care of them.

3)thinning of layers

Not all paintings must have this necessarly(different envirement might or might not make this occur). But certain painters’ work tend to to have the same issues more often. It might not be so obvious all the time as with potrait of lady Margaret. But number 5 has lines under eyes and sketches of brows which shouldn’t be visible.

So thinning of layer might suggest it is same artist. But also it can also mean master and apprentice, or same workshop. It’s definitely no proof by itself.

4)the fabric-how it is painted. In most of these recognizably it is crimson velvet. And while one time(number 5) it doesn’t have the vivid colour(probably because somebody else made the mixed the pigments), the style of this velvet is same or very similar. It could be same workshop, in several cases even same painter.

(I think it is possible that some people within workshop specialized in painting just 1 part of portrait-just fur, just velvet, just golden details, just the face. While in non-royal commissions(or not high status) perhaps 1 painter would be allowed to do even entire painting, I think for the high status, they’d really combine their skills for the best result.)

5)The other details-pearls, jewelry, hair, flowers etc.

Each of these can be as big as clue, as any of the much larger things.

Here very notable are the roses on number 2 and 3(again):

-that is by same hand for sure

if you look at neck of men in 2 and 3, you can also notice the same v-like shape.

That imo is not just painter’s skill showing-but hereditary feature between father and son(a detail which copies usually don’t bother to copy). Imo it’s this:

According to anatomy sketches on google-in that area should be jagular notch(the dip) between clavicles(which are to the sides and not forming that v) and then sternal head( sternocleidomastoid muscle).

So if the outfit allows you to see young Henry VIII’s neck in full, it might be there.

But number 5 already doesn’t have even hint of it and overall the visible differenes between the two are big. Yet experts say it is same by Wewyck(or his workshop):

And imo it’s indeed possible. The jewelry and gilded patterns are done in same way. The velvet too-but clearly somebody new mixed the pigment for the crimson-and it eventually faded away, and didn’t stay vivid as in other paintings.

But it’s just same workshop in different time.(and that is why you need experts to have look at those paintings and say-yeah this was also crimson, the drawing beneath is done in same way, etc. etc.)

Another detail are the male hats-often done in black, which hides the details actually), the type and size of hat can be helpful in dating the piece.

But rather often somebody tried to ‘correct’ the hat. It’s one of the most altered things on male portraits(imo). Very likely these portraits originally(3,6) showed same type of hat:

their hands also are folded in alost exact same way, and they sit same way.

Different roses suggest some time passed between their paintings, and noses do too(yes, in one he could be teen and in other adult), but their philtrum(that part above lip under nose), the chin, very likely at least sketched by same original painter, if the skin was not done by him too.

6)background

By now we know that very early work by Meynnart Wewyck(’s workshop) originally had blue background-very likely like this-blue fading into white, in lower part:

It reminds me of blue sky on nice summer day. Recently we had a lot of such days near my home, and especially when seeing the fields with grain growing and harvest aproching, several times I had thought-ideal day for grain harvest.

And in Tudor times, grain was staple of the diet, and good weather throughout the year and for the harvest would be crucial. So imo this kind of background symbolizes prosperity, good days, brought by the Tudor dynasty.

And the golden details at top of painting are also part of that background. But such background on its own is not enough of proof, it just helps to date the painting-because at certain times such background was popular and later it was not. Same goes with damask background. Such fabrics could spread around Europe and appear in paintings by multiple workshops. By its own, they are not a proof of same workshop. In Netherlands that’d be impossible to tell which imo. But in England, where there weren’t that many painters, it could help. If nothing else to pinpoint aproximate date when fabric with this pattern was fashionable(based upon other paintings featuring it elsewhere in Europe).

So imo both types of these backgrounds can actually be interesting detail to look out for.

However when it comes to damask backrgound, since most don’t survive in original nor good condition, finding two paintings with exact match can be extremely difficult. But not impossible.

But what I’d recommend against using as conclusive proof-is the skin.

Certain aspects of it such as thinning of it and shading, yes you can use that. But I know for sure that paintings of same person even if painted in exact same time by 1 same artist, if kept in different conditions/different envirement-the skin can look drastically different. Really different. Skin is not realiable proof, ok?

So can we find based upon these details more work of Meynnart Wewyck’s workshop? Well, not conclusively, we cannot prove it! Because the expert analysis and exhamination of the paintings would be also necessarly.

But we can find some where we see the same details as which I just listed above. So in part 2 I’ll show you some of those and my other picks for ‘possibly by Wewyck’s workshop’ and reasons why I believe experts should take look at them.

I hope you’ve enjoyed it.

#long post#historical portraits#meynnart wewyck#tudors#Lady Margaret Beaufort#henry viii#henry vii#henry vii of england#elizabeth of york

38 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Study for Solitude, c.1890 (chalk on paper) by Frederic Leighton, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, USA

#Frederic Leighton#fineart#art#painting#artwork#masterpiece#fineartprint#gallery#museum#solitude#chalk on paper#chalk#sketch#yale#yale center#british#british art#paul mellon#illustration

9 notes

·

View notes