#yanxia

Text

The Diplomatic Approach

#ffxiv#ff14#gpose#arcade artem#asahi sas brutus#midlander hyur#the doman enclave#yanxia#stormblood#stormblood spoilers#toxic yaoi for the toxic yaoi enjoyers

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch, cherry bomb

🌸Gorgeous outfit made by the even more gorgeous @/softfishie

#finalfantabee#gposers#ffxiv#final fantasy xiv#final fantasy 14#ffxiv screenshots#ffxiv gpose#midlander#hyur#cherry blossom#kyary#yanxia

26 notes

·

View notes

Photo

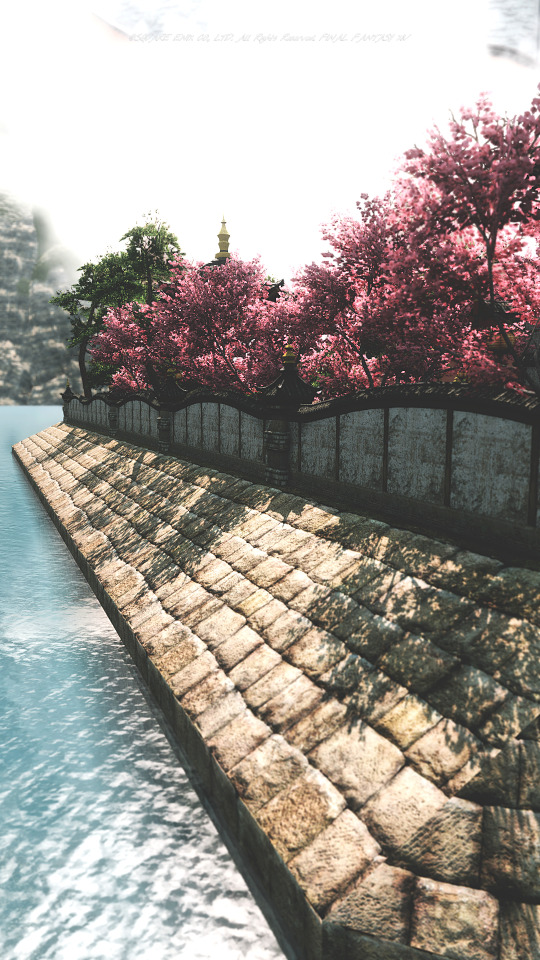

HANAFUBUKI FESTIVAL

[Balmung] Yanxia, Plum Springs

April 15th 8:00pm EDT

~~~~~~~~~~

Come join us for the traditional flower viewing! A beautiful moment in spring where we join together with friends and sit beneath the lovely cherry blossom trees to enjoy the Hanafubuki. We open the festival with a tea ceremony that leads into open market, and the evening closes with a themed play.

Currently in search of vendors, game stalls, fortune tellers, and geisha!

Come join our discord to get involved or to keep up to date with various Far Eastern festivals: https://discord.gg/YmBHZWxTtf

~~~~~~~~~~

INFO: https://hanafubukifest.carrd.co/

WHEN: April 15th 8:00pm EDT

WHERE: Balmung Yanxia, Plum Springs

Can't fly? We've got you covered, see our taxi service in Namai for a ride up to the festival.

#FFXIV#Roleplay#Blamung#crystal data center#Far Eastern Festival#Hanafubuki Festival#plum springs#yanxia

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

Roevember 2022 #11: Gold

The gold of sunset over Yanxia's hills.

It's always been her color.

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Prism Lake, Valley of the Fallen Rainbow, Yanxia

#More old screenshots from Twitter#ffxiv#ffxiv screenshots#final fantasy xiv#final fantasy 14#ffxiv locations#yanxia

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

XIVVGlamtober Day 17: Spring Flowers

This is the flower that shows us springtime beauty,

When the others have wobbled and fallen.

~Lu Bin

I’ve mentioned before that plum blossoms are the flowers that I associate most with Severia. They are a late Winter/early Spring flower that has many meanings such as resilience, perseverance, courage, strength and hope.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Day 13 - Stormblood

Yanxia was another mountainous region, but unlike Gyr Abania it had a generous enough smattering of green to put her heart at least a little at ease. Little trees sprouting throughout the villages and the flats of the rocky pillars embracing them. Rice fields arranged along careful shelves of land that must have been manually landscaped at one point, even as they so organically curved around the natural shapes of the environment.

The rice plants shivered and rippled in the early summer breeze, insects skating across the surface of the flooded paddies, weaving their way between the frogs and dragonflies seeking to make a meal of them as the crickets chirruped their unfamiliar songs.

But as the evening drew in, fireflies emerged with those lazy dances she knew so well, glowing yellow stars scattered across the fields and glinting on the water, promising to lead her back home.

For the Junelezen Challenge 2022

Previous Entries: Introduction / Calamity / A Realm Reborn / History Repeating / Eorzea Defended / Dreams of Ice / Warrior of Light / Heavensward / Floor the Horde / Gaol Break / Orthodox Mayhem / Five Minutes of Fate

#junelezen#junelezen 2022#oc: aurelle silmontier#yanxia#final fantasy xiv#stormblood#orime's stories

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Day 17: Nature

Rhemi and Diego adventuring around Yanxia

1 note

·

View note

Text

YANXIA - THE SEASONS OF CHANGE: The Rebirth of Eastern Civilization

Yanxian History Masterpost

Previous: Yanxia - East Allag

This third part describes the rise anew of civilizations in the Far East from the remnants of Allag following the empire’s most unceremonious end. How did our ancestors reclaim their dignity after a millenium of foreign rule? What gave birth to the shared identity of “Yanxia” we claim today?

The Rise of Kings (c. 4,700 y.a.)

Despite sequestration of knowledge from the masses in the wake of the Allagan Empire’s disintegration, societies in the east did not collapse entirely. While the state of technological advancement and scientific knowledge certainly regressed in the east much as it did in the west, the basic principles of agriculture survived as did some rudimentary metallurgy.

Across the centuries of this lost era, descendants of Othard’s ancient tribes fought amongst one another for territory and survival. While the various races of Othard had intermingled during the time of Allag, the collapse of social order in the wake of the empire’s fall saw many groups rally around claims of ancient lineages in a bid for power and comradeship. These resurrected tribes competed for dominance over the central plains along the One River, however few could ever claim the lands for long. Tribes regularly formed alliances to overthrow one another, then turned upon their former allies once their shared enemies were defeated.

During this time, Raen tribes along the mountainous border with the Azim Steppe who once enjoyed the favor of Allagan rulers exacerbated territorial conflicts as several groups pushed further south into the already violently contested plains along the One River. Outnumbered by more plentiful Hyur and Roegadyn tribes, and without the support of Allag, many Raen sought to assert themselves rather than give others an opportunity to attack first. Affirming their long-held reputation for martial prowess in the region’s bloody battles for hegemony, the fierce warriors of the Raen tribes made it clear that they could be a boon to those who favored them or a terrible threat to any who crossed them. While some Raen remained loyal only to their own, others joined forces with Hyur and Roegadyn to establish even stronger factions for the sake of shared profits. Not all Raen chose to make their home along the bloodied banks of the One River, however, and some tribes chose to move onward to other lands or sequester themselves deep within the hidden reaches of the region’s numerous mountain forests.

Toward the later part of this period, as taboos on knowledge and writing weakened, legends tell of a series of wise individuals who emerged in the central plains region and brought with them knowledge and innovations that advanced the lives of their people. Innovations in farming, textiles, construction, medicine, timekeeping, and even writing are attributed to these legendary figures. By sharing this knowledge with all people, they were seen as wise and virtuous leaders, and were even said by some to hold heaven’s mandate to rule. These leaders were crowned as kings, and with each ruling in turn then offering the throne to the most capable individual as successor, they established a period of relative order.

Yet as the so-called “dark age” following the Allagan abandonment of Othard progressed, numerous natural disasters brought great suffering to the central region of the continent. Flooding was most prevalent amongst these, with the One River unpredictably overflowing its banks to devastating effect. The destruction, famine, death, and disease left in the wake of each flood confounded leaders of the time. With the loss of technological knowledge resulting from civilization’s regression, the techniques that once might have been used to combat these floods were a mystery. Nor was magic a widely accessible option at the time, as many of Allag’s remaining mages had been hunted down and executed in the early days after the empire’s fall. Without the wisdom and knowledge of past mages, many people of the time could only utilize rudimentary spells and techniques.

At a loss for how to stop the floods, King Wu appointed the most skilled builder of the time to devise a solution. A towering Roegadyn named Gun (literally meaning “big fish”), this builder is said to have been descended from ancient nobility and perhaps even could trace his ancestry to the gods. Believing obstruction to be the appropriate method, this builder oversaw the construction of levees to guard against rising waters. By some accounts, these were constructed using magical self-renewing earth obtained from the sacred tower of Heaven-on-High, while others say Gun obtained the soil from the dragon lords beneath the sea. This magical soil was said to expand on its own upon contact with water, making it particularly well-suited to the construction of dams or levees. For a few years, this appeared to work. Yet after a time, the floods returned in greater strength than before. As the earthen levees rose higher from expansion due to water, they eventually could support themselves no more and collapsed, resulting in countless deaths. With the failure of the levees, King Wu’s successor Shu held Gun responsible as the master builder and sentenced him to death to placate the spirits of the deceased. Before his beheading, the disgraced builder bade his son Yu swear to succeed where he had failed.

The Founding of a Dynasty: Xia (c. 4,500 y.a.)

The origin of the first post-Allagan dynasty to dominate Othard is explicitly tied in most accounts to the legend of Yu taming the floods. As an adult, Yu became a trusted adviser to King Shu and took up his late father’s task. Living amongst the people, Yu sought their knowledge while carefully studying the rivers and lands of the region. Drawing upon the wisdom of farmers and other common people, he devised a solution drastically different from the one his father attempted. Instead of obstructing overflowing waters using levees, Yu chose to reduce the likelihood of flooding through redirection of river flows. To personally oversee the construction of canals and fields, he lived and worked alongside the common laborers, often in harsh and austere conditions. For years they toiled to construct an extensive network of canals that drained excess water into fields and opened new pathways for the river to flow into the Ruby Sea.

Before Yu’s project, the One River was not entirely free to flow towards the Ruby Sea. As the river flowed south from the Azim Steppe, its flow was limited by a narrow mountain pass that at times became dammed by the natural accumulation of river sediments. The formation of these natural underwater dams would cause great accumulations of water and energy until finally, it could be held back no more. Such a devastating release of water and physical energy would sometimes cause the river’s course to change as it sought the path of least resistance, potentially shifting the mouth of the river north or south by as much as 500 miles. To mitigate against such explosive releases of water, Yu personally led thousands of workers to the northern mountains and widened the pass, which allowed the waters to flow more freely.

Not content with merely redirecting the waters, Yu labored further to dredge the riverbeds of excess sediment that contributed to rising floodwaters. In all, the effort took thirteen years. Yet it proved to be a great success. In the many years following Yu’s grand project, not once did the river bring disaster. Instead, agricultural production surged as the waters irrigated countless fields and the region along the One River became known for its warm summer growing season.

For his contributions, King Shu rewarded Yu with a fief named “Xia,” meaning summer in the old language of the region. Yu and his descendants would take the name of their fief as their surname, a practice sometimes followed by the newly ennobled. As agricultural production grew following Yu’s stoppage of the floods, the Xia clan’s power and prestige rose within the royal court. In the later years of Shu’s rule, Yu was even given command of an army to bring peace to the southern border tribes. At the time, an alliance of Hyur, Roegadyn, and Raen tribal lords known as the Sanhao (Three Tyrants) had joined forces to exploit their weaker neighbors. Yu’s army swiftly defeated the three tribes, who were then exiled south of the One River’s lower reaches into what is today known as Nagxia. Of Yu’s many deeds, another notable act would be the division of central Othard into regions known as the “Nine Provinces” or “Jiuzhou.” At that time, these regions were established mainly as geographic distinctions based on Yu’s accounts of the kingdom during his projects, however later dynasties would eventually formalize these as administrative provinces.

Yu’s achievements and the power of the Xia clan were held in high regard, and when King Shu grew older and sought to abdicate to a suitable successor, Yu was considered without equal as a candidate. Thus, the throne passed to Yu upon Shu’s retirement and marked the beginning of the Xia dynasty. When Yu’s own reign eventually came to an end, his son would inherit the throne, ending the previous custom of bestowing rule upon the worthiest man and setting a precedent for the custom of dynastic or hereditary rule.

Summer Turns to Autumn: Xia Falls to Qiu (c. 4,200 y.a.)

Up until this point, many of the events described before and after Allagan rule have been compiled from oral histories and writings dating from much later periods than the events described. As such, the historicity of some previously discussed events and persons in these writings cannot be conclusively confirmed. The earliest verifiable post-Allagan records of Far Eastern history date from approximately 4,200 years ago, as the “Forgotten Age” following the collapse of the Allagan Empire neared its end in Othard. During this time, the ancient Far Eastern script of logograms first emerged as writing began to evolve from pictograms developed during the lost years.

Inscribed fragments of bone and shell “records” dating from this period document the presence of a well-organized kingdom along the banks of the One River in central Othard. Archaeological discoveries of bronze and jade artifacts in this region also provide evidence for some level of technological development.

The early records and artifacts from this period are generally ascribed to scholars and officials from an early dynasty known as Qiu, meaning “autumn.” Centered along the middle reaches of the One River, several hundred miles north of present-day Doma, records regarding the origin of Qiu are sparse and often merge with mythological tales of gods and kings.

The most recognized historical account of Qiu’s emergence involves the first post-Allagan dynasty, Xia, founded by the legendary Roegadyn river-tamer, Yu. After nearly three hundred years of rule by Yu’s descendants, Xia fell into decline at the hands of a corrupt and tyrannical ruler who was overthrown by the Hyur founder of the Qiu dynasty. Despite overthrowing the previous dynasty, the founder of Qiu is recorded as granting a title and token fief to the surviving Xia clansmen. This act is characterized by eastern scholars as a virtuous sign of the new dynasty’s respect for the previous dynasty and marked the passing of a divine mandate from one dynasty to the next. Many later dynastic changes would follow this example, establishing a custom known as the two crownings and three respects.

Sprawling ruins along the southern edge of the Fanged Crescent have been suggested by some as evidence for a well-organized civilization corresponding to traditional stories of the Qiu dynasty. This has been supported by the discovery of engraved tortoiseshell fragments documenting questions pertaining to matters of governance, such as agricultural activities, military movements, royal marriages, and much more. Yet owing to their relatively recent discovery within the past hundred years, many of these records have not been thoroughly deciphered. Furthermore, most discovered records are believed to date to the latter part of the Qiu dynasty. For these reasons, a thorough and well-established chronology or accounting of this period does not yet exist.

However, one can at least confidently say that trade routes which may have once connected the Three Great Continents under the Allagan Empire do not appear to have been restored by this time. The variety of artifacts attributed to this period is too limited in apparent origins to support any theories of extensive trade networks during the Qiu dynasty. Instead, Qiu would likely have been limited to trade and diplomatic relations with neighboring border tribes and small coastal settlements along the East Othard coastline.

Autumn Turns to Winter: Han Encircles Qiu (c. 4,000 y.a.)

As we arrive four thousand years ago, at the beginning of the “Age of Endless Frost” described by Eorzean historians, it is important to note that such an event may not have uniformly affected the Three Great Continents. Given that little of note appears to have been written by eastern historians regarding such a global fall in temperatures, some suspect this calamitous change had less pronounced effects in the Far East, allowing the persistence of a relatively favorable environment for ancient civilizations to continue in their development. The worst of the cooling climate’s effects in Othard may have largely been constrained to the northlands occupied by the Xaela tribes of the Azim Steppe and beyond, although famines and southward migrations of northern tribes were documented even in central Othard.

In the later years of the Qiu dynasty, the throne once again became tainted by depravity and cruelty. Inexplicably cooling temperatures that had swept from beyond the Azim Steppe caused widespread famine and discontent in the northern part of the kingdom, yet the King of Qiu refused to open the royal granary to feed the citizens. By this time, Qiu governance largely relied upon a clan known by the name of Wen which was linked inextricably with the Qiu royal family by marriage and political alliances. Much of the imperial court and military was controlled by the Wen clan, whose members held positions throughout all facets of government. As the King of Qiu became less and less predictable, paranoia and the whispers of his favorite consort persuaded the king to turn on the Wen clan, who he feared would seize his kingdom.

After forcibly securing the kingdom’s northern border by conquering several neighboring tribes who had fled south to escape the suddenly cooling climate of the far north, the eldest and most promising son of the Wen clan’s main line was ambushed by assassins. Evidence linked the assassination to the King of Qiu, provoking the Wen clan and its allies into open conflict with their ruler.

Declaring that heaven mandated the Wen clan replace the King of Qiu in the name of righteousness, the patriarch of the Wen clan gathered forces in preparation to march upon the capital. As word spread of Wen’s intent to rebel, popular support became increasingly vocal due to the ruthlessness of the King of Qiu at the time. When Wen forces advanced on the capital, many conscripted Qiu soldiers surrendered or even defected to the advancing army.

The conflict culminated in the Battle of the Western Plains, where the Wen armies destroyed the remaining Qiu loyalists in a bloody clash that forced the King of Qiu to retreat from the battlefield to the inner confines of the royal palace. In a final act of defiance, the King of Qiu set fire to the palace and locked himself within, choosing to burn to death rather than be captured or humiliated by the Wen clan. His consort escaped the blaze, however she was ultimately captured by the Wen patriarch and executed for her role in turning the king against them.

With the end of Qiu, the Wen claim that heaven’s mandate had passed to them was seemingly legitimized and efforts were immediately made to solidify their rule as the rulers declared the name of their dynasty to be “Han.” This name was allegedly chosen due to its archaic meaning of an enclosure surrounding a well, with the well in this case referring to the fertile lands of central Othard. A less popular theory also proposes it was selected due to being a homophone for another word meaning “winter,” which follows autumn in the order of seasons and would symbolize Han’s succession of Qiu.

The new rulers opened the royal granary and implemented a distribution system that moved the much-needed grain throughout the kingdom to parts most severely affected by famine. To strengthen the royal government, talented and virtuous Qiu officials were given offers to serve the nation and right the wrongs of the past dynasty. Despite the challenges posed by a changing climate, records show that the Han kingdom flourished as a time of cultural development. The beginnings of many established Far Eastern philosophies can be traced to this time, especially in the later part of the dynasty as great thinkers offered their talents to warring nobles.

The Language of Ritual

Under the Han dynasty, the old Yan language was enshrined in state rituals and ceremonies as the language of nobility, while the Nawa-influenced common tongue of Othard remained in daily use by most citizens. Written characters also evolved from the primitive script of the earlier Qiu dynasty into several additional scripts that served various purposes including one used for official purposes and inscriptions and another more ‘common’ script often used by scribes and low-ranking civil servants. It was during this time that “Yanxia” first appeared in records as a name for the Han dynasty’s territories and a common cultural ancestry ascribed to the tribes of central Othard. Despite cultural and administrative changes in later dynasties that would diminish the use of the old Yan language in favor of the more widely spoken Nawa-derived tongue, the name of “Yanxia” has persisted across millennia into the present-day.

Warriors and Scholars

At the peak of society during this period were the armed retainers of the royal family and warrior aristocracy. Known in the ritually significant old Yan language as “shi,” these were also described in the common tongue of Othard as “bushi” and “samurai” interchangeably. Masters in war and civil service, these ancient warriors have been compared by some to a similarly named class that developed in Hingashi. However, they differ in that the military role of mainland “shi” would diminish over time. Professionalization of the military and the development of a more extensive civil service administration gradually reduced the need to draw warriors from the aristocracy, while the needs of an expanded bureaucracy called for the skills of often well-educated and morally upright “shi.”

Eastern Feudalism

The feudal structure of early dynastic Othard was distinct from the earlier system of military feudalism instituted by east Allagan military governors in the Third Astral Era. First established by the kingdoms preceding the Xia dynasty, this system included several ranks of noble titles which the kings of Othard would confer upon their relatives and elite warrior allies along with inheritable lands through the act of enfeoffment. Unlike the earlier east Allagan military government’s feudal territories which were administered in the name of the emperor, lands allocated by the kings of dynastic Othard were fully transferred into the control of the receiving vassals as their own domains. These lands were not given as simple gifts, however, as the enfeoffed rulers of these vassal states were expected to pay tribute to their king and provide military support in times of war.

During the Han dynasty, this system created numerous states as the kingdom expanded east of the One River. In the early years, most fiefs were given to members of the royal house or their loyal allies while nobles from previous dynasties were relegated to small and distant domains on the periphery of the kingdom.

Winter Turns to Spring: Dukes Become Kings (c. 3600 y.a.)

Following an attack by an alliance of Raen and Hyur nomads from the northwest in the middle years of the Han dynasty, the royal capital was moved east of the One River. The move distanced the ruling Wen clan from its ancestral holdings and its logistical, military, and political costs contributed to the clan’s decline. At the same time, vassal states across the kingdom were gaining power and influence through conflicts with one another. As rebellious nobles, nomadic tribes, and other groups at the fringes of civilization threatened the Han borders, Han monarchs depended upon their most powerful vassals to conduct military operations against these threats. This dependency only further elevated the prestige and power of these powerful nobles to the point that they were effectively rulers of equal standing to the Han monarchs in all but name.

In the late years of the Han dynasty, the rulers of the vassal state Lu in the heart of the kingdom faced a succession crisis. Taking advantage of the unrest, several powerful families in control of various cities in the state collectively deposed the Duke of Lu and divided the state amongst themselves. These families became the de facto rulers of three new states. However, the division of Lu removed one of the chief rivals to the neighboring state of Cui, which upset the balance of power as previously negotiated spheres of influence between Lu and Cui were negated. With the appearance of a sudden power vacuum, competition for hegemony between states began anew.

As borders shifted and the rulers of various states grew in power from their conquests, some nobles determined the time was right to cast off pretenses. First among these was the Duke of Cui who had grown dissatisfied with lesser titles of nobility after conquering several other states. (For clarity, “Duke” or other foreign feudal titles are only used here as loose translations and not wholly equivalent to the titles used in western feudal systems.) Believing a more suitable title was needed to match his accomplishments, the Duke of Cui made the unprecedented decision to declare himself King of Cui, effectively claiming his state’s independence from the Han dynasty. Other nobles would soon follow suit as they too consolidated power over the lands in their vicinity, marking the beginning of the Warring States period.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

𝐹𝐶 𝐶𝑜-𝑙𝑒𝑎𝑑𝑒𝑟𝑠 ℎ𝑒𝑟𝑒 𝑡𝑜 𝑓𝑢𝑐𝑘 𝑠ℎ𝑖𝑡 𝑢𝑝

#ffxiv#ff14#miqo'te#miqote#ffxiv gpose#ffxiv black mage#ffxiv blm#au ra#ffxiv reaper#FFXIV RPR#yanxia

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

testing out vfx editing with two flavors of foxy grandpa here

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A jorogumo and a kitsune hanging out on the mountain.

@akai-ffxiv

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

#final fantasy screenshots#ff14#ffxiv#final fantasy 14#final fantasy ffxiv#yanxia#stormblood#scenery

3 notes

·

View notes