#yiddishkeyt

Text

Allgemeine Zeitung des Judentums, vol. ix (1837), p. 264. A Jewish-German periodical devoted to Jewish interests, published in Leipzig and later Berlin from 1837-1922.

183 notes

·

View notes

Note

We live in a small town and only have two synogauges. One of them is orthodox and when I tell you how excited the rabbi was to find another jewish family, it was immense.

He texts us about shabbos and always gives us things for events in case we want to tag along. (We arent orthodox but trying to reconnect which makes me see how genuine these small acts of kindness are).

I dont want to sound as if im generalizing so I specifically say this to the community I found here, its like receiving cards from home from a family you haven't seen in a long time.

Compassion, for those who come from different places in their judaism. And welcoming to those who haven't returned home in a long time.

I was watching a video recently in which a Chasidic woman discusses her experiences and says, "I'm in love with yiddishkeyt. Wild horses couldn't drag me out of this." I find that's how a lot of observant Jews feel, that we take the term "tribe" very literally. A jew I've never met is my family. When I see antisemitic incidents I mourn as if it happened to my brother or my sister. I mean it, I am in love with Yiddishkeit too. Of course he is excited a new Jewish family moved in! It's like your siblings moved next door after not seeing them for years!

My soul knows yours from Sinai. It is always a great schande to me when some Jews can't see/feel this kinship.

#jumblr#jew#jewish#judaism#frumblr#jewblr#antisemtism mention#antisemitism#yiddishkeit#i hope converts can grow to feel thiss too#ask

109 notes

·

View notes

Text

It makes me a little sad when Judaism gets summed up as ‘ethical monotheism,’ and people try to present it as this very clear, rational sort of thing. Because, it’s true, it is that, but it’s also dybbuks, and ghosts you can sue in court, and Lillith who comes in the night, and amulets to keep away Lillith who comes in the night, and changing your name when you’re sick so Death can’t find you, and secret codes and mystic math, and smashing glasses at a wedding to scare off the demons.

And do I believe in those things? No, but I think I might need them.

When I was a kid I went to Hebrew school and we talked about how to worship G-d, and we never mentioned the little things we still do at weddings or when babies are born-- those times when you can’t be too careful, when you have a happiness worth protecting with new and with old ways.

And I grew up with Jewish religion, but absorbing Christian superstition, and I didn’t learn until much later that we had our own Jewish superstitions, and Jewish names to give our fears, and Jewish ways to make ourselves feel safe from them.

As a mostly-secular American Ashkenazi Jew, a lot of what’s been passed to me has come to me from institutions: my synagogue, which naturally tends to capital ‘R’ Religion; and political and cultural organizations, that tend to focus on the rationality and the potential universality of ethical values. And I think it’s worth thinking about what isn’t transmitted that way, and what gets lost, and maybe making more space for embracing our own particular weirdness and irrationality.

I don’t know, I just have a lot of feelings about folk religion all of the sudden.

#jumblr#yiddishkeit#yiddishkeyt#i'm on my period and it's making me weirdly emotional about Jewish demonology and folklore#so sorry

834 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z6ygwpfuFHw

Tonight we bid farewell to (C)han(n)nuk(k)a(h), and we zoom full-throttle into the world of Christmas. Parties, slightly manic merriment, lights, decorations, jingly carols on the radio, Toyotathon Sales Events . . . the whole world is reminding us that we are a Minority, and a weird one at that. But as we dig into our Chinese food and search for a good movie on Netflix, we can experience the warm holiday glow of knowing that half the reason that Christmas music is so good is that a lot of it was written by Jews!

With that in mind, YidLife Crisis has decided to . . . let’s say . . . “gently reclaim” some of our artistry. If you feel that there’s a certain Yiddishkeyt missing from all of those Jewish Christmas tunes, never fear. A transfusion is here!

Yingl Belz, yingl belz . . .

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

American Jewish Culture: The Literary Communities’ Reaction

After learning about the crisis of the Jewish population in Eastern Europe, and trying to understand the reasons the American general population showed little support to those persecuted by the Nazis, I must ask; How aware were American Jews of the situation overseas, and what was their reaction at the time? To understand the American Jewish reaction some knowledge of the Jewish culture of the time needs to be had. Jews who had emigrated from Eastern Europe before the war, or to escape the growing anti-Semitism, brought with them the language of their heritage. Yiddish was the main form of communication of the Jewish population from Eastern Europe and a strong signifier of their culture. As time went on, Jews (especially those who were born in America) began to adapt to English, diversifying the culture away from their “old country” roots. The Jewish culture in general has very strong ties to academia stemming from the commitment to Torah study. This academic tendency led to the publication of many Jewish journals in English and in Yiddish, providing lasting evidence of the knowledge the Jews had of Hitler’s actions and their reactions toward it.[1]

Firstly, it is important to note that many scholars believed that “American Jewry” was “rooted in the air,” meaning that the culture was not truly grounded by location or by its people. Yiddish was still a factor keeping Jews tied to each other and to their heritage, but as assimilation to American trends and standards grew more popular, Yiddish would begin to disappear, only remembered by deeply isolated sects and as a language of historical and cultural study. Yiddish has become the most direct connection to the European Jewry that was wiped out by Hitler. The common nostalgic view of “true yiddishkeyt” (immersion in Jewish culture) that disappeared from Europe due to the Holocaust has also mostly disappeared from modern America and is only acknowledged now as a preservation of the destroyed roots of an ancient heritage. From the study of old Jewish journals, it has been found that no single culture bonded all Jews in America. There was a combination of responses from those of Jewish heritage; chosen language, political affiliation, and religious commitment all altered individual responses to the actions of the Nazis. One thing is clear; Any person who picked up a journal focusing on Jewish issues from 1938-1944 would have been fully aware of the atrocities occurring in Europe.[2]

The Contemporary Jewish Record took careful steps to ensure they reported on news from around the world in their publications. It started as early as September of 1938 when they reported on the large numbers of homeless refugees who were not being taken in by other countries, to September of 1939 when they reported that 358 patients were killed in a Jewish hospital bombarded by German forces. They published the terrifyingly escalating conditions for Jewish safety straight from Polish sources in early 1940, stating: “There is no parallel to the brutalities which are being inflicted on Jews in this region.” Jewish journals made an extensive effort to keep their readers aware of the fate of their brothers across the ocean. Although the acknowledgement of the horror was there, little political action seems to have been affected. Jewish scholars insisted in their writings on the need to preserve the Jewish culture and create an environment that could welcome refugees. This is most clear in Yiddish literature, the contents of which focused on the mourning and consolation of Jewish survivors. This may have been the key to the death of Yiddish as it became a “yortsayt kultur” (a culture that commemorated deaths). In English-language Jewish journals, the response to the Holocaust varied in an extreme way. After the war many Jewish writers, who wrote in English, shied away from speaking about the Holocaust and even felt alienated from their Jewish culture. After experiencing the annihilation of millions of their people overseas, many felt as though their pasts had been lost and sought an existential understanding of the events that unfolded. A sense of survivor guilt spread across the more assimilated Jews, while a deep sense of despair echoed through Yiddish writings. However, the attitude that the Holocaust had changed the meaning of being Jewish permeated through all Jewish groups.[3]

[1]Norich, Anita. 1998. “`Harbe Sugyes/Puzzling Questions’: Yiddish and English Culture in America During the Holocaust.” Jewish Social Studies 5 (1/2): 91–110. doi:10.2979/JSS.1998.5.1-2.91.

[2]Norich

[3]Norich

0 notes

Text

Yesterday I was sad i would not get to be in a sukkah today i learn my apartment is a sukkah

1 note

·

View note

Quote

יעדער מענטש װערט געבױרן פריי און גלייך אין כבוד און רעכט. יעדער װערט באשאנקן מיט פארשטאנד און געװיסן; יעדער זאל זיך פירן מיט א צװײטן אין א געמיט פון ברודערשאפט.

Article One of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, in Yiddish.

2 notes

·

View notes

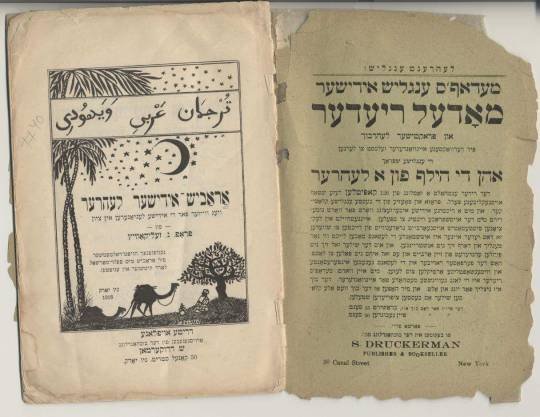

Photo

Arabic language self instruction book in Yiddish, 1918.

22 notes

·

View notes

Conversation

example interaction in my yiddish textbook

לייבל: אויב זי איז אזוי קלוג, פֿאַר וואָס איז זי ניט רײַך?

leybl: oyb zi iz azoy klug, far vos iz zi nit raych?

leyble: if she's so smart, why isn't she rich?

מאַשע: ווײַל זי האָט ניט געוואָלט. זי איז אַ סאָציאַליסטקע.

mashe: vayl zi hot nit gevolt. zi iz a sotsyalistke.

mashe: because she doesn't want to be. she's a socailist.

#EVERYONE has that perpetually gardening barefoot kibbutz aunt!#yiddish#yiddishkeyt#יידיש#יידישקייט#jews#judaism

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Have you ever been “in a pickle”?

Then you have encountered Rotwelsch, an ancient language of the road, spoken by vagrants and refugees, merchants and thieves since the European Middle Ages. This tongue was based on a combination of German, Yiddish, Hebrew, a smattering of Romani (the language of Sinti and Roma, pejoratively known as Gypsies), Czech, and Latin—and was incomprehensible to all but initiates.

I was inducted into this strange language during my childhood in Southern Germany. My earliest memories were of strange figures, dressed in long coats that had lost their original colors, who showed up at our door with bags slung across their backs. When it rained, they smelled, and my mother wouldn’t let them inside the house. “I know what you want. Wait. I’ll be right back,” she would say.

Lingering near the door, I would hear noises from the kitchen, my mother fixing open-faced sandwiches. While they ate, she remained standing on the threshold, guarding the house, trying to make conversation. I had trouble understanding them because they spoke a strange dialect, mixed with words I didn’t know. When they had finished, my mother would take the empty plate from their hands and close the door, relieved that the encounter was over.

“Who are they?”

“They don’t have a home. We’re giving them something to eat.”

That didn’t answer my real questions. I wanted to know why: Why didn’t they have a home; why were we giving them something to eat; and why did they have such a strange way of talking?

Later, I asked my father about these men and their language. “They are Travelers,” he said.

I didn’t understand. “Where are they going?”

“They are people of the road, escaping to nowhere.”

My uncle eventually figured out why these travelers kept showing up at our house. One day, he found a sign discreetly carved into the foundation stone, a cross with a circle around it, which meant that there was bread to be had here. The signs were called zinken, a word derived from the Latin signum. But the language was Rotwelsch, also known as kochemer loshn, an adaptation of the Hebrew khokhem, which means a wise person and loshn, tongue, or language.

It was a language of those in the know, the lingo of the wise guys. These signs and words pointed to an underground of traveling people; a world hidden away from view. Over centuries, outcasts had developed this secret world, with its coded lingo, to protect themselves from a world hostile to strangers (Rotwelsch means beggar’s cant). Their special language bound migrants together, because it distinguished those who belonged to the road from those who didn’t.

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Holy Poem

by H. Leivick, translated from the Yiddish by A. Z. Foreman

With my holy poem

Clenched between my teeth

From my wolf cave—my hole, my home—

I go out and I roam

From street to street:

As a wolf with a wretched bone

Clenched between his teeth alone.

There is prey enough in the street

to sate a wolven hate,

and sweet

is the humid blood that drips

from flesh, but sweeter still

is the dry dust settling

down on jammed lips.

Struggle on the street,

The call of throats.

Let me this once come out tonight,

A deathtooth bite.

That bite is me.

But I don't come to gnaw.

I hunch into my little self

With head beneath my paw.

Back to my hole I head

And lump onto my bed,

But I am awake,

Untired from holding clenched

Between my teeth alone

This holy poem

As the wolf his wretched bone.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Record

by Gabriel Preil, translated by Grace Schulman

The poet reads lines

about the credences of summer.

The glass in his hand hides

And rekindles

a small fire;

a delicate wisdom flares;

the beauty of things

cannot be exhausted.

but the voice of the poet

recalls a shadowy sailor

cast up on a desolate shore

far from every certainty

#‘CAUSE PEOPLE BELIEVE THAT THEY’RE GONNA GET AWAY FOR THE SUMMERRRRR (j/k. but not really)#gabriel preil#grace schulman#poetry#yiddishkeyt#heat 2 midrash

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

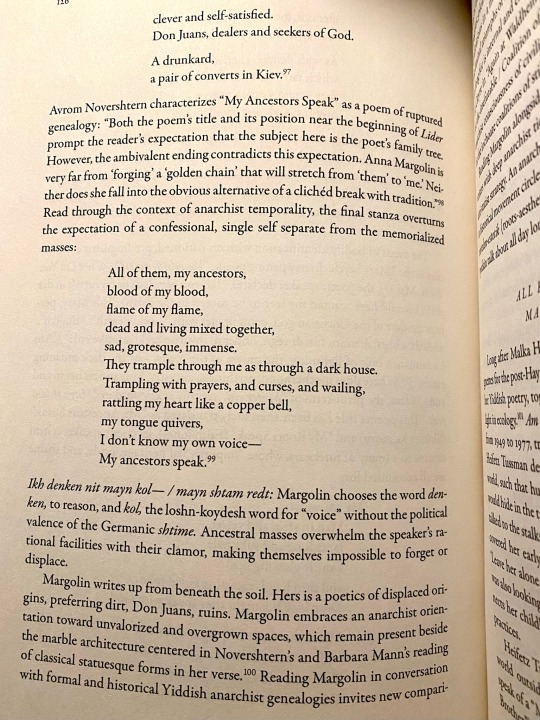

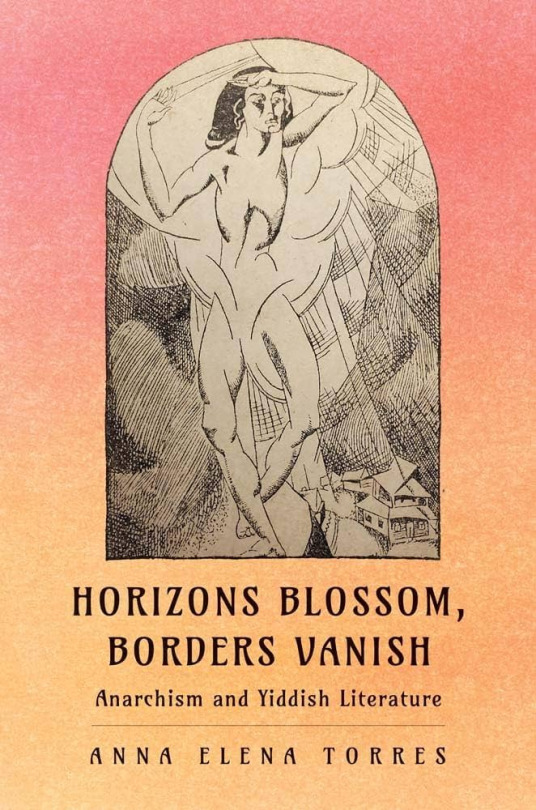

Taking a break from Archive Fever and Freud and Daniel Paul Schreber to page through Anna Elena Torres’s book on Yiddish literature and anarchism, which came out, like, last week. I’m feeling refreshed, rejuvenated, invigorated even,

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Spanning the last two centuries, Horizons Blossom, Borders Vanish: Anarchism and Yiddish Literature by Anna Elena Torres combines archival research on the radical press and close readings of Yiddish poetry to offer an original literary study of the Jewish anarchist movement.

Torres examines Yiddish anarchist aesthetics from the nineteenth-century Russian proletarian immigrant poets through the modernist avant-gardes of Warsaw, Chicago, and London to contemporary antifascist composers. The book also traces Jewish anarchist strategies for negotiating surveillance, censorship, detention, and deportation, revealing the connection between Yiddish modernism and struggles for free speech, women’s bodily autonomy, and the transnational circulation of avant-garde literature.

Rather than focusing on narratives of assimilation, Torres intervenes in earlier models of Jewish literature by centering refugee critique of the border. Jewish deportees, immigrants, and refugees opposed citizenship as the primary guarantor of human rights. Instead, they cultivated stateless imaginations, elaborated through literature.

I'm attending the YIVO Zoom discussion on this book which is on February 12 at 1 PM ET and it's free to register.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Perhaps the article goes into this, I don't know, but a subject that I rarely see talked about and that I have undertaken as a sort of personal passion project — closely entwined with my favorite Jewish American filmmaker, as I'm sure is obvious lol — is the destruction of a distinctly Jewish secular-humanist idealism and aesthetic culture, the failure of imagination that results from having a readily accessible and inspiring alternative to the imposed narratives of Western culture (conquest, domination, technological and industrial development, etc). For this it's hard not to blame the depredations of Nazi Germany + the specific American postwar stage of antisemitism, economic opportunity, religious freedom, and communist hysteria. In this scenario, assimilation becomes the path of least resistance for a traumatized population taking root in a new country (and those who were there since the 1880s had in large part fled the pogroms, so any way you slice it you see the specter of annihilation hanging over Jewish emigration and resettlement). What structures form the ultimate telos of assimilation into a Western imperialist paradigm...? Church (American Synagogue) and State (its ties to Zionism).

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

6 notes

·

View notes