#yugoslav poetry

Text

"Just cross my mind,

My thoughts will scratch your cheek

Just come into my sight

My eyes will bark at you

Just open your mouth

My silence will break your jaws

Just remind me of yourself

My remembering will dig up the ground beneath your feet

That's how far we've come."

— Vasko Popa, "Give Me Back My Rags"

#Poetry#Poem#Literature#Vasko Popa#serbian poet#serbian poetry#serbian literature#yugoslav poetry#Modern Serbian poetry#Modernism#Moderna#Art#Words

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

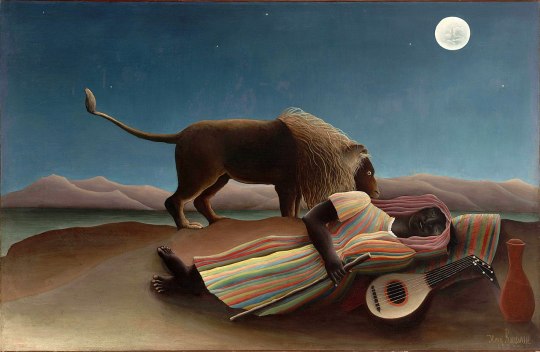

~~ Ivan V. Lalić, "In Praise of Sleeplessness" (translated by Francis R. Jones), painting by Henri Rousseau

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Stop a person on the street in Sarajevo and ask them what they think about the war in Ukraine, and they’ll tell you they think that almost everything that happened in the war in Bosnia-Herzegovina is happening in Ukraine.

In April, we commemorated the 30th anniversary of the war against Bosnia-Herzegovina. We consider early April 1992 the moment a new era began: we have the before, during and after the catastrophe.

A month into the war in Ukraine I saw Ukrainians starting to use the phrase “before the war”. We went through everything that’s happening to them, but no one asks us about it or wants us to help.

War leads you to start looking at life and death with different eyes. Before our “smallish war” (an ironic phrase I use in literary works), I wanted to be a poet and wrote ultra-metaphorical and incomprehensible poems. After the war, I was determined to write as clearly and precisely as possible, especially about the events of the war. That is when I became a writer. The war was a giant catalyst in that process.

In a recent article for the Paris Review, Ilya Kaminsky quoted the Ukrainian poet Daryna Gladun on how events in Ukraine had changed her writing: “I set aside metaphors to speak about the war in clear words,” she said, “so that readers around the world will be struck by the cynicism, cruelty, and inevitability of the war that Russia brought to Ukraine.” A number of Sarajevo poets found the same thing happen during the siege of this city – the longest in the history of modern warfare. The famous Slovenian poet Tomaž Šalamun once said that he stopped writing poetry entirely during the war in Bosnia.

On 21 April 1992, the attack began on my home town in far western Bosnia. I was studying in Zagreb at the time but returned to Bosanska Krupa because I knew the war would soon begin; regular and irregular Serb formations had begun attacking towns in eastern Bosnia in early April.

You could see towns burning along the river Drina, the natural border between Bosnia-Herzegovina and Serbia, even though the country was still called the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. But not even the letter Y remained of Yugoslavia because Slovenia, Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina declared independence and seceded from it.

I was drinking beer and listening to music on the terrace of the Casablanca cafe in Bosanska Krupa when the attack came. I remember I was wearing Levi’s, a down jacket and Adidas trainers. It was a lovely day, but shortly after 6pm an artillery attack began. That’s when I realised what the expression “in mortal terror” means. Militants of the Serb Democratic party, aided by forces of the former Yugoslav People’s Army, shelled the city from the surrounding hills.

I neither volunteered nor was I conscripted. We were surrounded by enemy forces and there was no way out of the area (later called the Bihać pocket or Bihać district) unless you could fly. I took up arms because I was driven out of my flat, my street and my neighbourhood. My conscience demanded that I fight.

For 44 months I fought as a soldier and later as an officer leading a unit of 130 men in difficult combat operations at the very end of the war. Once I was badly wounded in the left foot and needed crutches to walk for six months. The pain was more or less bearable because I was young and my body had the strength of steel. We didn’t have time then to think about the transcorporeality of pain, nor about infatuation with our own.

I remember having to go to the toilet in a special wheelchair, which had a hole in the seat. But I recovered quickly, I returned to the unit and to the same duties I had before the injury, as a platoon commander of 30 men.

Chronological time stops ticking during war. We wore watches on our wrists but they showed a meaningless time. We were cut off from the rest of our country and the civilised world. We were five hours’ drive from Vienna, at least before the war. Now we lived as if we were at the end of the world, so time was irrelevant. A new time was ticking inside us – the one you count from the moment your idyllic, civic life collapses and you become a refugee. After the first moments of shock, we were quick to embrace the apocalyptic way of life.

The experience of war is not something you want. No sane person wants it. It’s a return to the stone age and the time of commodity-money exchange. In the war, you could sell a toothbrush, a tube of toothpaste or a pocketknife and then get tanked up with the money. We did that once: we went to a town far behind the lines, drank beer and listened to Whitney Houston singing I Will Always Love You on MTV. It’s not as if we were Whitney Houston fans. We preferred grunge, and before that we listened to new wave, but no one asked us about our musical or any other identity.

We didn’t even know that the Serb nationalists saw us as the Others, to be expelled from “Serbian lands”, killed, raped and imprisoned in concentration camps. In the summer of 1992, when the Serb army and police occupied the town of Prijedor, all non-Serbs had to wear white armbands and hang white sheets out the windows of their houses and flats. The genocide began there, and it ended with the court-proven genocide in Srebrenica in July 1995. The phrase “never again” was repeated in the Prijedor concentration camps in the summer of 1992 and is now being repeated in Ukraine.

Although I and my family, comrades-in-arms and fellow citizens went through the worst possible suffering (as refugees, soldiers and civilians), I’ve never allowed myself to hate an entire people. I’ve only hated ultranationalists and war criminals, not other Serbian people.

We had to fight for our sheer survival. And when you fight like that, you can never be defeated because no idea is stronger than the idea of your own life. Right now, Ukrainians are fighting a life-or-death struggle. Having nothing to lose but your own life is when you’re strongest.

In the autumn of 1995, we finally managed to retake our town. It was in ruins, but we rebuilt it. Years after the war, you realise that life will never be the same as it was before. Once you lose that Arcadian life it can never be renewed.

All this is not what concerns the people of Ukraine at the moment. They hope the war will end as soon as possible, but war has a logic of its own that is nothing like human logic. The aggression against Ukraine has all the characteristics of a long war of attrition.

The day the war in Ukraine began, I wrote on Twitter that the Russians would commit war crimes, even though they hadn’t yet occurred. It was clear to anyone who watched and listened to Vladimir Putin that war and atrocities would soon follow. He referred to Ukraine as a fake state and the Ukrainians as a fake people.

Slobodan Milošević and Radovan Karadžić said the same things about Bosnia-Herzegovina and Bosniaks – that they were fake and didn’t deserve to exist. Those words were later turned into the worst crimes in Europe since the second world war. I hope the crimes of the Russian army will not surpass those committed in my country.

We will discover the full extent of atrocities and crimes of the Russian invasion of Ukraine when the war is over. The most important thing is for the Russian war machine in Ukraine to be broken and brought to a halt. The dictator understands only the language of force, while the politics ofappeasement bolster his power. People in the EU will have to leave their comfort zone because that is the sacrifice required of them while Ukrainians are fighting and dying to maintain peace and prosperity in the EU. If Ukraine is defeated, we will never again live in the peace that currently prevails.

The cities of Ukraine will be rebuilt from the ashes. The whole country can rise again. What cannot be brought back are the dead. These wounds never heal, but you can live with them, and you have to. The trauma of loss marks you and never leaves you. But I believe in the grit and courage of the Ukrainian soldiers and citizens, just as I believed in us. I believe in the victory of life over death.

Faruk Šehić is a Bosnian poet, short story writer and novelist

This essay is part of a series, published in collaboration with Voxeurop, featuring perspectives on the invasion of Ukraine from the former Soviet bloc and bordering countries. Translation by Will Firth

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

Critics are so quirky baby girl why are you writing about Yugoslav bards this is about Old English dream poetry

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

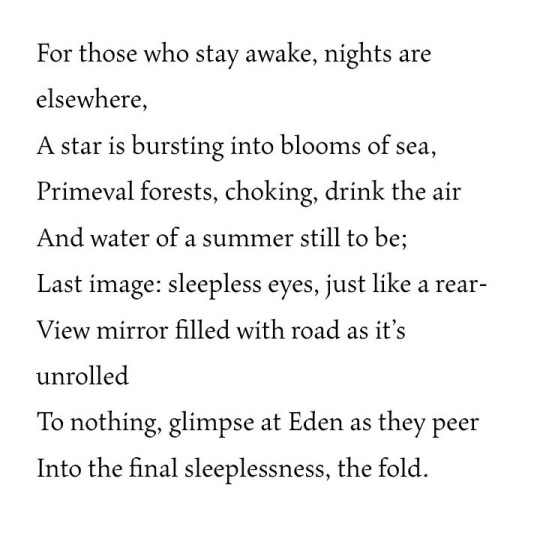

Mark your calendars for our AWTS fall edition this September 22nd, at 8PM at (of course) Molasses Books featuring: Alex Braslavsky, who will be reading her translation of Zuzanna Ginczanka's poetry collection On Centaurs & Other Poems (World Poetry Books), "Here I preach passion and wisdom / tightly conjoined at the waist / like a centaur"; Jennifer Zoble with Sweetlust by Asja Bakić (Feminist Press), a heady fusion of feminist critique and science fiction, "Occasionally disturbing and always intoxicating," (that's BUST), as well as Kosovo-born Finnish author Pajtim Statovci (with many thanks to Todd Portnowitz and Rose Cronin-Jackman at Knopf/PRH) who will be reading from Bolla, translated by David Hackston, an incredible novel set during and in the aftermath of the Bosnian War...there is ill-fated love at first- and last-sight, the two men swept up in each other, their linguistic-escape: "...and when I see that his books are in English we switch languages. Though improbable, random even, it feels natural, because by speaking English we can be different people, we are no longer ourselves, we are free of this place, pages torn from a novel."

***

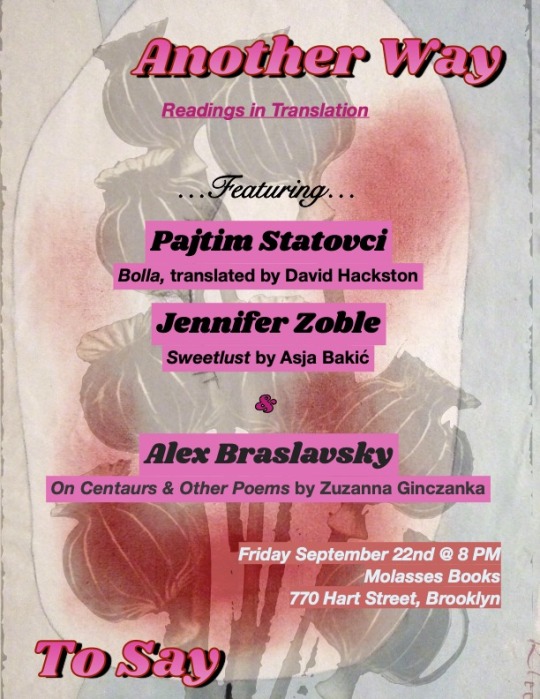

PAJTIM STATOVCI was born in Kosovo to Albanian parents in 1990. His family fled the Yugoslav wars and moved to Finland when he was two years old. He holds an MA in comparative literature and is a PhD candidate at the University of Helsinki. His first book, My Cat Yugoslavia, won the Helsingin Sanomat Literature Prize for best debut novel; his second novel, Crossing, was a finalist for the National Book Award; and Bolla was awarded Finland’s highest literary honor, The Finlandia Prize. In 2018, he received the Helsinki Writer of the Year Award.

JENNIFER ZOBLE translates Balkan literature into English. Recent books include Sweetlust by Asja Bakić (Feminist Press, 2023) and Call Me Esteban by Lejla Kalamujić (Sandorf Passage, 2021). Her translation of Mars by Asja Bakić (Feminist Press, 2019) was named one of the Best Fiction Books of 2019 by Publishers Weekly. Zoble is on the faculty of Liberal Studies at NYU, where she teaches writing and translation, and coordinates the university's new undergraduate minor in translation studies.

ALEX BRASLAVSKY is a poet, scholar, and translator working towards her doctorate at Harvard and working on Polish, Czech, and Russian poetry. She is the translator of On Centaurs & Other Poems (World Poetry Books, 2023) by Zuzanna Ginczanka. Her poems appear in The Columbia Review, Conjunctions, Colorado Review, and more.

0 notes

Text

The Golden Circle Of Time by Aco Šopov

Olden star, star of prophets and wonders, –

burst into verse, sink down into the blackest darkness.

This mad light lasts more in blood

and this invisible flame that has no sign nor name.

Starry ghost, star of a cold nightmare, –

disappear with all the fortunetellers with all the fallen myths.

Under this trunk of words planted on a hundred year crust

a dreadful fire is being lit and hungry roots are burning.

Who are you that comes with scars from the dust of a distant age,

with a time long unsounded into irreversibility,

and instead of the air of a poor man in despair

you bring a cruel law for yourself and your kin?

Voice yourself with a scream of silence, speak out with a mute glance,

arched in your speech with nods powerfully threaded,

and like an unnecessary warrior with black earth eyes

look around in the golden circle and victoriously fade out.

Olden star, star of prophets and wonders, –

burst into verse, sink down into the deepest word,

while this mad light lasts in the blood

this underground fire, this eternal ember.

2 notes

·

View notes

Quote

The Return

Who knows (ah, no one, no one knows anything.

Knowledge is so frail!)

Perhaps a ray of truth fell on me,

Or perhaps I was dreaming.

Love may still happen to us,

Happen – I'd say,

Though I do not know whether to want it,

Or not want it, anyway.

In the sea of life that constantly boils,

That constantly evaporates,

Perhaps the same drops

Are re-created and reconciled.

All over again.

And when eternity

Passes on its starry path,

Its futile round.

The same lips may be again

In a passionate kiss found.

You may show up one night,

Beautiful in a blue dress.

Unaware that you poured your light

Over my ancient days.

And I, writing with heart full of you,

These strange rhymes,

Oh, I won't even know, yearning of my being,

Your name at times.

Even if the soul in that moment

Its ear strains,

With an assured voice the reason will silence

All premonition whispers.

By the evening lamp-posts we shall secretly

Like strangers at each other glance,

Without a slightest knowledge

How much we are linked

Through some old chains.

But time moves, time moves

Like the sun in its course,

And what was in the past to us returns:

The sorrows and the joys.

And the eyes will shine, hands will meet,

And the hearts will lift -

And blind to the footsteps of our former feet

Towards them we shall drift.

Who knows (ah, no one, no one knows anything.

Knowledge is so frail!)

Perhaps a ray of truth fell on me,

Or perhaps I was dreaming.

Love may still happen to us,

Happen – I'd say,

Though I do not know whether to want it

Or not want it, anyway.

Dobriša Cesarić (1902 — 1980) - ,,Povratak” (The Return)

0 notes

Text

User guide for CROATIA or DRAZEN KRLEZA

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Dear (name),

Thank you for ordering from Yugotalia Corp. Here is a list of instructions for caring for your new Yugoloid DRAŽEN unit!

We are not responsible for any damage made to you or your house.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Your DRAŽEN unit comes with :

One (1) DALMATIAN DOG unit

Two (2) ties and one (1) bow tie

One (1) suit

One (1) military outfit

One (1) poetry and fairytale book

Three (3) bottles of rakija

One (1) guitar

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Technical Specifications:

Name: Dražen Krleža. Will also reply to " Croatia", "Hrvatska", "Cro", "Selfish bastard", "Serbia" but he won’t be happy if you call him the last two names....

Age: 23

Place of manufacture: Zagreb, Croatia

Height: 175cm

Weight: TOP SECRET

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------

PROGRAMMING

DRAŽEN is equipped with following traits:

Singer/Guitarist He is pretty good at singing and better at playing guitar. So if you need a good singer or guitarist in your band, you can use him!

Fashion model Need money? Don’t worry! DRAŽEN has the most beautiful beaches in Europe after all, so you can make him be the Fashion model!

Teacher He is good at teaching Croatian and he would be better art/poetry teacher!

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Removal of DRAŽEN from box

1. Play Croatian anthem really loud. He will jump out of the box and start singing along. While he is singing you can reprogram him.

2. Play Serbian anthem. He will jump out and look around house to find SERBIA. When he clams down you can reprogram him.

3. Make some croatian food and put it next to box. He will open the box and start eating. While he is eating you can reprogram him. He will later give you a little rakija as thank you for food.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Reprogramming

After getting him out of the box, you can reprogram him to following modes.

Grumpy (default)

Hotheaded and proud (default)

Gentleman

Protective brother

Romantic

Sad

OCC

First two mods are his normal personality.

Gentleman mode is what it means. And he will call you Master/Miss/Lady etc.

Protective brother mode means he will be the over protective sibling you never had....

Romantic mod, you will have to find it out yourself

Sad mod is basically when you remind him of Yugoslav wars, WW2 or WW1. Or any other war. (he hates wars) He will probably lock himself in his or your room for a few weeks.

OCC is when he acts VERY diffrent than usual.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Relationships with other units

SERBIA : His arch-rival is Serbia and Croatia will do anything to keep him away from his house and friends. If you put them together in romantic mode and lock them in your room for few weeks, you can espect some Serbo-Croatian babys....

SLOVENIA : He was actually pretty good friends with Slovenia, until they started having fights over their backyards. Croatia calls Slovenia a whiny bitch, since he is quite a crybaby to the EU when it comes to this, while Slovenia calls Croatia a selfish bastard since he simply won't let go.

BOSNIA : DRAŽEN sees him as his little brother, he cares about him. If you want them to have babys than you have to put them in romantic mode and wait few months.

HERZEGOVINA : She is his cousin and they get along.

GERMANY : He is DRAŽENS BFF. But even Germany is a bit afraid of Croatia's anger button.

ITALY : They were enemies before but they are friends now. They can have romantic relationship if you want.

Everyone else : Most of other units like him becouse he lets them visit his beaches.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Cleaning

He can clean for himself and he can clean himself. If he trusts you he will want you to take a bath with him. If you see his scars, dont ask him how he got them, it will make him depressed/sad.

Feeding

He loves Balkan and slavic food, but he will eat anything you give him.

Rest

He loves to sail to islands. He sleeps whenever he wants to. Dont wake him up or he will go to his special mode. He also loves romantic films, books and Dating simulation games. He enjoys a good football game too! He loves to go to irish pubs.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

FAQ

Q: His dalmatian dog is gone and he is too!

A: Dont worry, he will come back as soon as he finds his dog.

Q: He looks like he wants to kill me!

A: Congrats! You unlocked his INSANE MODE! He will want to kill you and if he fails he will go and kill half of your town. He is good at hiding it so dont worry about police. You can get him out of this mode by talking to him for a few hours.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Problem:

I did not get DRAŽEN. I got some little cute kid that speaks only croatian!

Solution:

We send you a Little!Croatia! If you want you can send him back and your DRAŽEN will come in few days!

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

He is actually quite polite, hospitable, caring and fun to be with, behind his egoistic facade.

If you want any other Yugotalian or your Yugotalian is broken call this number: 066-545-7878-22 .

So i saw some people do this and i was like why dont i try this with yugotalia?

im sory for my bad english1

DON’T REALLY CALL THAT NUMBER.

-Laura

-Bruzi (fixed typos)

18 notes

·

View notes

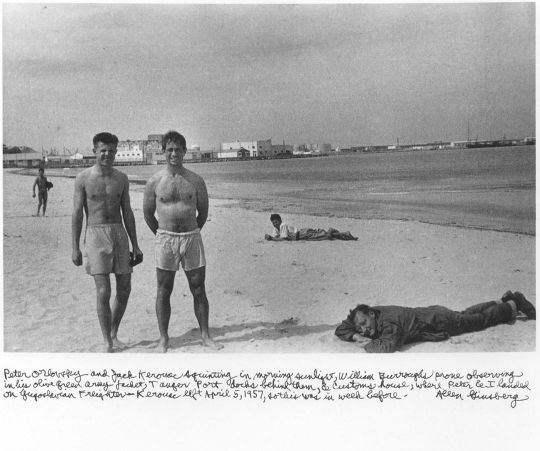

Photo

Peter Orlovsky & Jack Kerouac squinting in late-afternoon sun, William Burroughs with eyeglasses prone in olive-green Army surplus jacket, watching, Moroccan boys interested, Port & Custom-house in background where Peter & I docked on Yugoslav freighter from New York carrying four years accumulated Naked Lunch manuscript-letters. Jack speed-typed Burroughs Interzone word-hoard, his own On the Road just (about to be) published, Peter readying to write his own Frist Poem. (sic) Jack left Tangier for Paris a week later, April 5, 1957. (photo & caption: Allen Ginsberg, courtesy Stanford University Libraries / Allen Ginsberg Estate) • #allenginsberg #jackkerouac #peterorlovsky #williamsburroughs #beatgeneration #writers #poetry #poetrycommunity #ontheroad #nakedlunch #junky #counterculture #photography #morocco #tangier (at Tangier, Morocco) https://www.instagram.com/p/CAyJeEIhYoZ/?igshid=q2mc7g58zn22

#allenginsberg#jackkerouac#peterorlovsky#williamsburroughs#beatgeneration#writers#poetry#poetrycommunity#ontheroad#nakedlunch#junky#counterculture#photography#morocco#tangier

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Robert Pesich

Poetry allows you to have these feelings, to explore your grief and joy. Poetry is a spit in the eye of the monster—a knife in its gut.

When Robert Pesich arrived at his new Sunnyvale middle school sporting a tan leather briefcase and a hint of a Serbian accent, the school bullies must have rubbed their meaty paws together in anticipation. Having recently arrived in the neighborhood, his Yugoslav…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Text

"My true love has never been given away as much as I could and as I desire,"

— Desanka Maksimović, "Spring Poem"

#poetry#serbian poetry#serbian poet#desanka maksimovic#literature#art#serbian literature#poetess#yugoslavia#yugoslav poetry#quote#quotes#love#spring poem

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mesa selimovic sjecanja pdf

MESA SELIMOVIC SJECANJA PDF >> DOWNLOAD LINK

vk.cc/c7jKeU

MESA SELIMOVIC SJECANJA PDF >> READ ONLINE

bit.do/fSmfG

Mehmed "Meša" Selimović was a Yugoslav writer, whose novel Death and the Dervish is one of In his autobiography, Sjećanja, Selimović states that his paternal Tvrdjava mesa selimovic pdf free download [6][7][8][9] In his autobiography, Sjećanja, Selimović states that his paternal ancestry is from the Orthodox MEHMED MESA SELIMOVIC Ro en je 26. aprila 1910. godine u Tuzli. Ovako se mjesaju utvare i zivot, pa nema ni cistog sjecanja ni cistog zivota. Mesa Selimovic- Sjecanja Library Bookshelves, Literature, Library Shelves, Ostrvo – Meša Selimović Literature, Poetry, Book Jacket, Library Bookshelves. Mesa Selimovic, Sjecanja, Detinjstvo u proslosti, str.27,. Bgd,2001. Source 9. Women pilots. In the 30's of the last century, after a few successes of. Sjećanja (Croatian Edition) [Selimović, Meša] on Amazon.com. *FREE* shipping on qualifying offers. Sjećanja (Croatian Edition) Download as TXT, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd Arthur Golden - Sjecanja Jedne Gejse.mobi Magla i mjesecina - Mesa Selimovic.mobiSjećanja [dr. Mehmed "Meša" Selimović, 1990.] April 30, 2017 | Author: Tiskarnica | Category: N/A. DOWNLOAD PDF - 34MB. Share Embed Donate. Report this link

https://moluxuweso.tumblr.com/post/667797964112183296/harry-potter-novel-in-tamil-pdf, https://hufutunuceg.tumblr.com/post/667811125855911936/foxpro-report-sample-visual, https://hexuwufugoxi.tumblr.com/post/667753292899778560/tubidy-3gp-vedio-mp3, https://tedabajati.tumblr.com/post/667749250641362944/notice-vistaquest-fs-501-n, https://felojumepa.tumblr.com/post/667762604174983168/ss-guide-for-llb-entrance-exam-pdf.

0 notes

Text

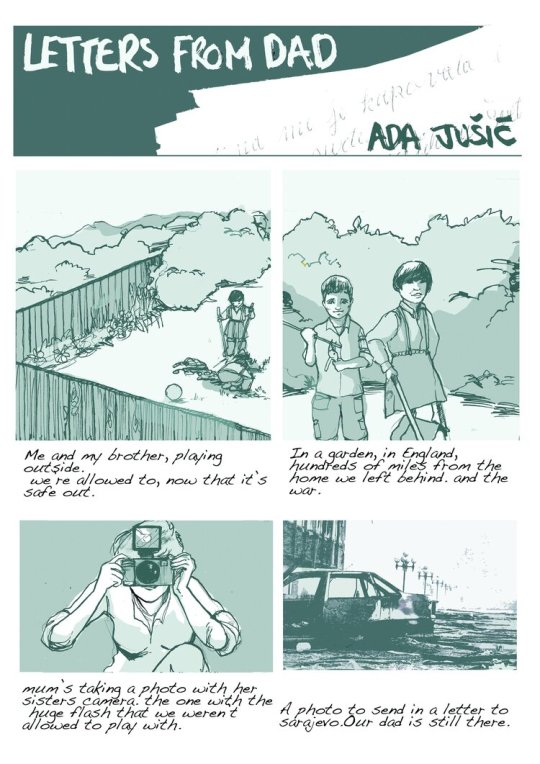

To be Heard is to be Loved

by Ada Jusic

In the hallway of my parents’ house hang paintings I did as a five year old. On the surface they look no different from any other cherished childhood artwork - daubs of cheap bright poster paint and the vague shapes of people and houses. They’re lovingly framed and displayed. However these were not just paintings of our house or people I saw; they were representations of our journey to the UK as refugees fleeing Bosnia during the Yugoslav war. Look closely: there are two suns in one of the paintings, a colourful one and a dark one, representing our new, peaceful home and our dangerous war-torn one. A blobby figure made up of splodges is a soldier with a gun.

I did the paintings shortly after arriving in the UK. A family friend who was an artist and my childminder would give me her old paints and brushes to use. I loved the different colours and the act of marking the bright, clean paper -- marking it with my memories and experiences. I suppose it was a sort of art therapy. I was shy and withdrawn at school. Teachers wrote on reports that I didn’t smile or laugh. I struggled to express myself in class and got into trouble sometimes as a result, but I would use the paint sets and colouring pens at every available opportunity. When I was painting and drawing, I felt I could express everything I held inside of myself. This wouldn’t be the first time I would turn to creativity to make sense of my experiences as a refugee, but something I would go back to time and time again.

My teens were spent trying to be as ‘normal’ as possible, and though I was always an obsessive doodler, I only really started to explore my identity through art again going into my twenties. My first return to Bosnia after the war at the age of 14 was traumatic. The marks of the conflict were still evident all over my hometown Sarajevo and my long absence meant that I felt as out of place in my home country as I did in the UK. However, by the time I was 19, I had started to take an active interest and pride in my identity and during a second return to Sarajevo made friends and started to feel the beginnings of a reconnection. I had also started art school and, like a real art student cliché, found my experiences as a refugee and feelings of being an outsider were becoming the subject of my projects. I discovered artists like Art Spiegelman and Joe Sacco who also made art about war and the refugee experience. I was really into comics and graphic novels; I still am. With every project, with every comic and sketch and drawing, I gained a new and deeper understanding of my and my family’s journey.

Today I work as an illustrator and animator and the refugee experience still figures large in my professional practice. I used to feel conflicted and sometimes I still want to have an identity cut free from that of a refugee and a survivor, to have a clean and shiny slate the way I perceive others (who don’t have this experience) do. But my experience of being a refugee is an inextricable part of me and I think is a reason why I now help others to explore their stories and experiences of being refugees. I have worked with organisations such as The Worldwide Trust and English PEN to create animations in collaboration with other refugees. One of my animations, Zeinah, tells a Syrian woman’s story of why she made the decision to leave her home. Another project was made with young people living as asylum seekers in the UK who worked together the ways they could translate stories of loss and hope into poetry and moving images.

There’s a saying that being heard is so close to being loved that, for the average person, being heard and being loved are indistinguishable. Every time I put pen to paper or created a comic, I was making myself heard, understood, and loved -- by myself as well as by others. And when I help others make their voices heard and understood. I see the spark of joy that comes with being heard, understood and loved.

Ada Jusic is a professional illustrator, animator and designer. She has been working freelance for over 6 years for a wide range of both corporate and grassroots clients and believes that illustration should involve asking questions, looking and listening; it shouldn't just be decoration. Born 1987 in Sarajevo, Ada came to the UK as a refugee in the early 90's. Very early on she was fascinated with image and storytelling, going on to study illustration to a Master's degree level in London.

You can view more of Ada Jusic’s artwork and animation — including Zeinah’s Story and Brave New Voices — here.

Twitter: @AdaJusic

Instagram: @AdaJusic

0 notes

Photo

Alain Badiou's foreword to Pier Paolo Pasolini's unrealised St Paul

Saint Paul: A Screenplay - http://bit.ly/2xRmau6 - Free delivery worldwide

"It is well known that the Christian reference played a role of primary importance in the formation of Pasolini’s thought, despite (or because of) the sexual and transgressive violence that inspired his personal life and bestowed a particular coloration on his communist political choices. In a certain sense, it was a sacrifice bordering on the sacred – the mysterious death of his brother, an Italian partisan, probably killed by the Yugoslav resistance at the moment of Liberation – that led both to his view of the judgement one can make on History, and to the severity he displayed, from the late 1950s on, towards the Italian Communist Party. Basically, the PCI was guilty in his eyes of having allowed the young people of the Resistance to die without legitimate heirs or genuine political paternity, which led also to abandoning to their fate the young proletarians of the modern housing estates. Among other texts, the broad and splendid poem Vittoria presents the history of this denial, suggesting in the background the denial of St Peter: by denying Christ, Peter had shown too much attachment to his own safety; and against Paul, at Antioch, too much attachment to the old rituals that limited the universality of the message.

It was Peter, rather than Paul, who prefigured the sclerosis of the Church, and likewise that of the PCI. Consider this passage, which stigmatizes the ‘realism’ of political parties, caught in the ‘mysterious debate with Power’ and deaf to the voice of young people in revolt:

… Joyous

with a joy that rejects any second thought

is this army – blind in the blind

sun – of young dead, who come

and who await. If their father, their leader,

leaves them alone in the whiteness of the hills, in the peaceful plains – absorbed in a mysterious debate

with Power, enchained to its dialectic

that history forces him unceasingly to reform –

quite gently, in the barbarous hearts

of the sons, hatred gives way to love of hate.

More generally, Pasolini relentlessly confronted the forms that a life devoted to the naked truth of the subject could take vis-à-vis the avatars of the Passion and the pitfalls of holiness. If we compare him, for example, with Bataille, it is easy to maintain that it is with much more sincerity, exposure to risk, and poetic gift that Pasolini made the dialectic of abjection and the sublime his own. If we compare him with Genet, we have – though in this case equal in terms of quality – the whole difference between sublimation by way of poetry (or the cinema) and sublimation by way of prose (and the theatre). The former orients itself towards origins, fables and myths, the figures of history (Oedipus, Christ, St Paul, Dante, Gramsci) the latter to an intimate tale mingled with and borne up, as it were, by the latent breath of the history of peoples: underclass prison angels, prostitutes, blacks, Palestinians… But in every case, on the horizon of meditation lies the question of religion. Not as a possibility still open, there is no question of believing in it, but as a poetic and historical paradigm of the possibility of scathing confrontation, at the heart of individual and collective existence, with the implacable truths that religion can express and with the meaning it may or may not receive from the world such as it is.

It is indeed this rift between meaning and truth that is at issue in the figure of Oedipus, as Pasolini’s very fine film restores him: as soon as one discovers the truth (murder of the father, incest with the mother), the only meaning that life still finds is in blindness and death. But this is also the figure of Christ: so that truth will come to the desert world of men, God must present the absurdity of his own torment. Hence the power of the film that Pasolini drew from the Gospel According to St Matthew. And is it not tempting to see Pasolini’s own death, which remains so obscure, as the Passion of true desire fulfilled in sacrifice under the insensate knife of the person this desire encounters?

It is only too natural, in this context, that St Paul should have been a tutelary figure for Pasolini. He saw him, in fact, as the first embodiment of the conflict between political truth (communist emancipation being the contemporary form of salvation), and the meaning this could assume in the weight of the world. In our world, in fact, truth can only make its way by protecting itself from the corrupted outside, and establishing, within this protection, an iron discipline that enables it to ‘come out ’, to turn actively towards the exterior, without fearing to lose itself in this. The whole problem is that this discipline (of which Paul is here the inventor under the name of the Church, like Lenin for communism under the name of the Party), although totally necessary, is also tendentially incompatible with the pureness of the True. Rivalries, betrayals, struggles for power, routine, silent acceptance of the external corruption under the cover of practical ‘realism’: all this means that the spirit which created the Church no longer recognizes in it, or only with great difficulty, that in the name of which this was created.

Paul is one of the possible historical names of the tension between fidelity to the founding event of a new cycle of the True (metaphorically, the resurrection of Christ; actually, the communist revolution) and the rapid exhaustion, under the cross of the world, of the pure subjective energy (holiness, or totally disinterested militancy) that the concrete realization of this fidelity would demand.

Pasolini wanted to make a major film on the dialectical character of Paul. This would essentially be a sequel to his film on the Passion of Christ: the history of the Church, which, as guardian of the meaning of this Passion, propagates and perpetuates its truth effects, and also the history of the failure of this guardianship. He did not find financing for this film. But we have a very detailed scenario of it, a scenario that in my view is in itself a literary work of the first magnitude.

As he did in his Oedipus Rex, Pasolini juxtaposed the ancient reference with the contemporary, but in a very different manner. The action of Saint Paul, in fact, is situated completely in the contemporary world, whereas in Oedipus Rex, the contemporary drama with the mother ‘duplicates’ the connected visibility of the legendary tale. What pertains totally to antiquity in Saint Paul is quite simply, and exclusively, the apostle’s own words, the text.

We might say that in Oedipus we have a ‘distribution of the sensible’, in the meaning that Jacques Rancière gave this expression, the history – the legendary text – being distributed between two different regimes of visibility, the ancient and the modern. In Saint Paul, on the other hand, the sensible is homogeneous (it belongs to our world), while a large part of the intelligible (what is thought and uttered), being drawn from the epistles of Paul or the Acts of the Apostles, is a reproduction of the antique.

Pasolini’s wager, therefore, is that the truth of which St Paul is the divided bearer, the sacrificed militant, can make sense in the world of today, thus proving the latent universality of his thought. We can see the United States in place of Rome, the intellectual snobs of Rome (whom Pasolini hated) in place of the philosophers of the Athenian agora, or echoes of collaboration and the Resistance in France: Paul’s text crosses all these circumstances intact, as if it had foreseen them all.

What this meant for Pasolini was that all corruptions resemble one another, declining empires and their exhausted valets resemble each other, and the betrayers of all truths exposed to lack of meaning all wear the same mask.

With stupefying virtuosity, Pasolini manages this very risky construction, in which the invariance of a text that bears truth – the invariance, basically, of the Idea – is shown, in the Passion it supports, as having to find an acceptable meaning in unappropriated worlds.

This scenario should be read, not as the unfinished work that it was, but as the sacrificial manifesto of what constitutes, here as elsewhere, the real of any Idea: the seeming impossibility of its effectuation. Pasolini was scarcely optimistic as to the possible metamorphosis of this impossible-real in a world that would finally have meaning. Do we have reasons to be more optimistic than he was? The existence of Pasolini’s poems and films is certainly one of these reasons, as optimism has never been anything but a pessimism overcome by its own subject, in the work of universal significance that, against all expectation, this has produced."

Saint Paul: A Screenplay - http://bit.ly/2xRmau6 - Free delivery worldwide

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

We're ringing out National Translation Month at Molasses Books, September 3oth at 8PM, with an incredible trio of translators-writers. Plugging Asymptote hard here to direct you to both S.J. Pearce's new translation(s) of Psalm 9 that reveals the psalm's many-voiced awe and resentment, and a selection of Suzana Vuljevic's translation of "Airplane Without an Engine" by Ljubomir Micić with a white sharp "Hellooooooooooooooooooo / I leap headlong into my ideoplan". If you had the good fortune to attend Us&Them's November 2021 reading, you'll remember Jennifer Shyue, whose translations of Julia Wong Kcomt's poetry has been published by Ugly Duckling Presse's Señal series as Vice-Royal-ties.

***

S.J. Pearce is a writer and translator who lives in New York City. Her poetry has appeared in The Laurel Review, The Reform Jewish Quarterly, Orotone, and Second Chance Lit, as well as in the anthology Strange Fire (Teaneck, 2021); she has also work forthcoming in Asymptote and The Plenitudes. Her first chapbook manuscript was a finalist for the Laurel Review's 2021 Midwest Chapbook Competition and she was long-listed for the 2021 River Heron Review Poetry Prize. She is a member of the 2022 cohort of the Brooklyn Poets Mentorship Program. In the scholarly realm, she publishes on the history of translation in the medieval Mediterranean world. Her first academic monograph was the recipient of the 2019 La Corónica International Book Award.

Suzana Vuljevic is a historian, writer and translator who works from Albanian and Bosnian, Croatian, Montenegrin, and Serbian. Suzana holds a Ph.D. in History and Comparative Literature from Columbia University. Her writing and translations have appeared in Zenithism (1921–1927): A Yugoslav Avant-Garde Anthology (Academic Studies Press, 2022), AGNI, Asymptote, Eurozine, Exchanges, and elsewhere. She is a 2022 ALTA Travel Fellow and an editor at EuropeNow.

&

Jennifer Shyue is a translator from Spanish and an assistant editor at New Vessel Press. Her work has appeared most recently in AGNI, Astra Magazine, and Poetry Daily. Her translations include Julia Wong Kcomt’s chapbook Vice-royal-ties (Ugly Duckling Presse, 2021) and Augusto Higa Oshiro’s novel The Enlightenment of Katzuo Nakamatsu (Archipelago Books, 2023). She can be found at shyue.co.

***

THROUGHOUT THE REST OF SEPTEMBER Trafika Europe Radio's programming will feature international authors and works in translation from the likes of Thora Hjörleifsdóttir with translator Meg Matich, Victor Jestin with translator Sam Taylor, Italian poet and novelist Daniele Mencarelli, and more!

MONDAY SEPTEMBER 19 at Greenlight Bookstore's Fort Greene location, Emma Ramadan presents her translation of Barbara Molinard's Panics in conversation with Kate Zambreno

SUNDAY SEPTEMBER 25th at the Parkside Lounge, the Spoken Word Sunday Series presents a special event for National Translation Month featuring Soodabeh Saeidnia and Adriana Scopino.

TUESDAY SEPTEMBER 27th in the virtual realm, Words Without Borders presents World in Verse: a Reading and Celebration of International Poetry with Najwan Darwish, Kareem James Abu-Zeid, Samira Negrouche, Marilyn Hacker, Jeannette Clariond, Samantha Schnee

***

Eager to see you in your sweaters and cords! xoxo, Janet

0 notes

Text

I Know by Ćamil Sijarić

I know that in this late autumn

in this very late autumn

in Šipovica, the rose hips redden

If only the wind would - even a little

Spread their colors over me

on my hands,

on my face -

For I see that this autumn

the rose hips in Šipovica

will redden for me

for the last time

4 notes

·

View notes