Text

TCC 16 Nov 2023 update.

ds- is respelt as tz- to keep it in line with "traditional-looking" Romanizations (such as in "Yangtze River").

zh- may be considered a variant spelling with j-. The two initials may be conflated under j-, pronounced [(d)ʑ].

<aa> is again an accepted substitute for <â>, especially when tone marks are added.

-io is still yu when followed by an initial.

For the rationale behind the n-/ṇ- (nr-) distinction, see the previous version.

Previous version

1 note

·

View note

Text

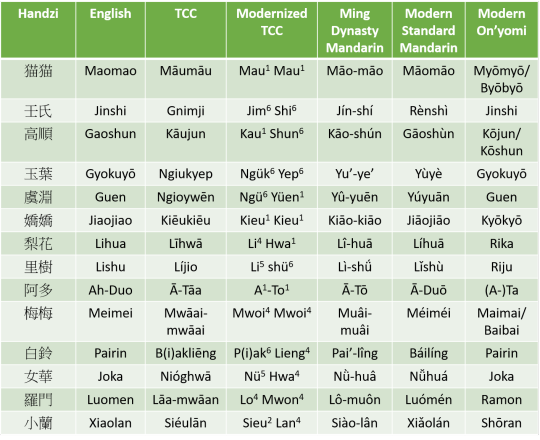

A table comparing the names of the characters in Apothecary Diaries in different languages.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

In line with the aesthetic goals of basing on existing romanizations, the "ds" initial will be respelt "tz".

1 note

·

View note

Photo

I decided to try transcribing my name (as pronounced in Middle Chinese/TCC) into Hieroglyphs.

Perhaps I should have used the double feather instead, to emphasize on the non-syllabic nature of the “i” in “khiēm”.

Edit: i (single feather) was changed into y (double feather). I decided to formalize this change after reading that "<j> is written as <jj> word medially".

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

Sorry if this bothers you, but at this time, do you still offer copies of ParseRime? the post with the original download is seven years old now...

I am not the creator of ParseRime, not have I ever hosted downloads for it. I had made more recent posts on ParseRime with updated links, such as this one here (this is one of the links in the blog description): https://tcchinese.tumblr.com/post/664458763946917888/%E6%9E%90%E9%9F%BB%E8%BC%B8%E5%85%A5%E6%B3%95-parserime-ime

Also, as the intended post format of this blog is not for conversations, please ask questions non-anonymously so I could answer them privately. I will make an exception this time.

0 notes

Text

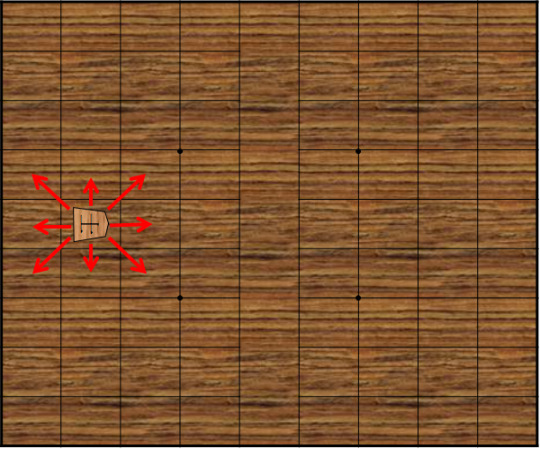

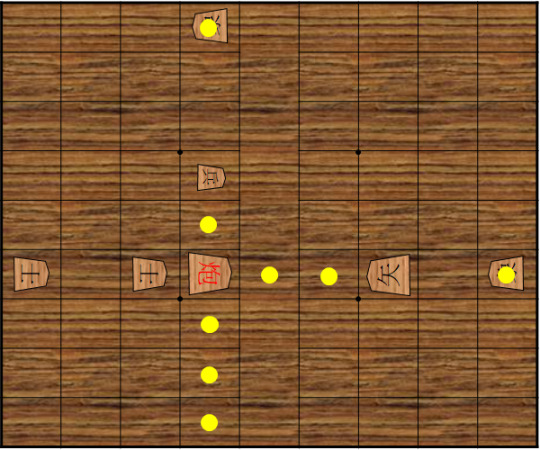

琅野将棋 (Rangya canggi)

(The following article outlines a fictional variety of chess created for the constructed world of Rangya)

Canggi (将 棋, Yenmun: 장끼) is the traditional variety of chess native to the Kingdom of Rangya. Chess forms were first brought to Rangya when Rangya had contact with Japan, and later perfected when Rangya traded with China and Korea. Heian Shogi (平安将棋) was introduced to Rangya first and for a while was enjoyed by locals along with Korean janggi and Chinese xiangqi. Some time later, some proposed merging the 3 forms of chess to create a unique variety, which has since spread.

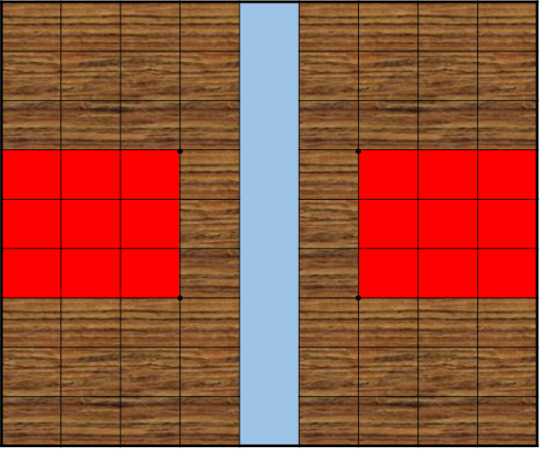

Canggi is played on a board of 9 by 9. There are 3 special areas on the board:

The areas highlighted in red are the palaces (宮, jul), marked by the 4 dots on the board, known as stars (星, ami). It serves as the promotional zone for most pieces. The vertical strip in the middle is called the river (川, ruru), and affects the pawns. Even though no lines run between the 2 banks of the river, the river strip is still counted as having separate squares and not one big square.

Due to characters like 車 (and that in the ancient times, pieces were only written with black ink), it is hard to tell which side has the piece. Therefore, pieces are pentagon-shaped, pointing towards the opponent, so that one could easily tell which pieces belong to who. The pieces also vary in size, with the smallest being the pawns, the biggest being the rooks, knights, and cannons. The guards and elephants are medium-sized.

As Heian Shogi had no drops (Japanese: 打つ), canggi does not either.

The pawn (兵, peng) moves and captures one space forward. If it has crossed the river, it gains the ability to move one space sideways. If on the river, since it has not yet crossed it, it moves only one space forward. If a pawn enters the opposing palace, it promotes to a guard (士). Promoted pieces stay promoted throughout the rest of the game and aren’t demoted. Promotions are not mandatory.

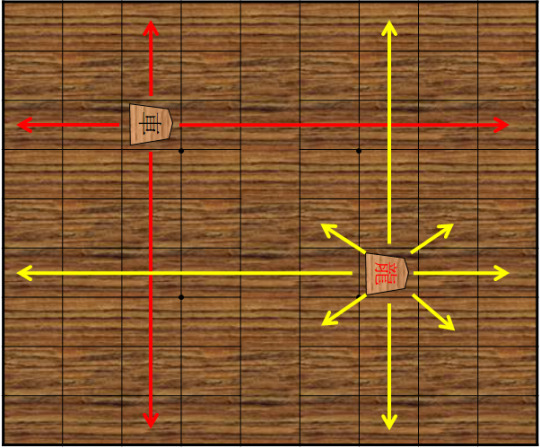

The rook (車, chya, “chariot”) moves orthogonally as many spaces as desired, like a Western chess rook. If it enters the opposing palace, it promotes to a dragon (龍, rong), which gains the ability to move one space diagonally. The dragon was borrowed from the later Dai Shogi (大将棋), as it did not exist in Heian Shogi.

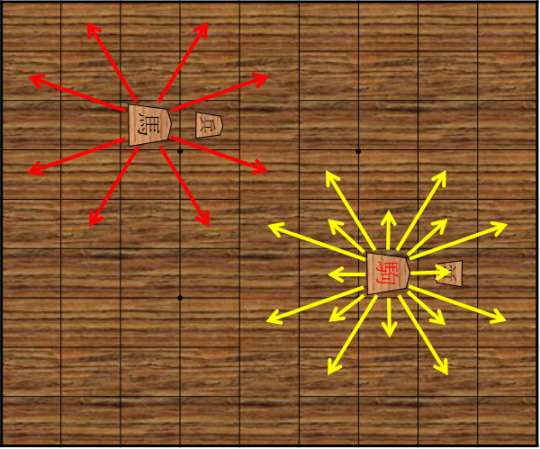

The knight (馬, ma, “horse”) moves the same as the Western chess knight. It is a result of merging the Chinese/Korean knights (who cannot jump) with the ability to jump over pieces from Japanese shogi. The promoted knight, the foal, (駒, kyu, “young but strong horse”) moves like a knight and a general. While the foal is an original piece from Rangya, the name of the piece is adopted from the word for a chess piece in Japanese (駒, Japanese: koma).

The minister (相, sang) moves 2 spaces diagonally. Like the knight, it is allowed to jump over pieces. Note that the 2 ministers protect the central pawn in the starting positions and are able to attack the opposing palace. Unlike xiangqi, elephants may cross the river (from Korean janggi). The promoted minister, the elephant (象, zang), moves as a (3,2) or (2,3) leaper (e.g. like the fairy chess piece zebra), jumping over any intervening pieces. Note that the minister could actually only reach 12 squares on the entire board. After promotion, the elephant is able to reach any square on the board, though due to awkwardness in movement, players may choose not to promote it, as promotion is not mandatory. The move of the elephant is adapted from Korean chess.

The guard (士, ji) and the general (将, cang, stylized 將 on canggi pieces) move 1 space orthogonally or diagonally. Neither of the pieces promote. Unlike the Chinese and Korean generals and guards, they are not confined to the palaces. In the early days of Rangya canggi, the guards had a more limited movement and both them and the generals were confined to the palace, but it was quickly realized that it did not make for a balanced game considering the powers of the other pieces, so this rule that they were confined was lifted.

The arrow (矢, si) has a similar move to the Korean cannon: it moves in an orthogonal line, jumping over the first piece on the line (friend or foe) and can land on any number of spaces beyond until it reaches another piece. If that other piece is an enemy piece, the arrow may capture it. If the other piece is a friendly piece, the arrow must stop before that space. The arrow is not allowed to jump over another arrow (to prevent capture of the opposing knight on the first move), though it may capture another arrow.

The promoted arrow, the cannon (炮, pho), moves like the Chinese cannon: when not capturing, it moves as a rook; to make a capture, it jumps over the first piece in line (the screen) and captures the second piece in the line, provided that it is an enemy piece. It is allowed to jump over another arrow or cannon in making the capture.

Some terms:

Check: 将軍 (cangkun)

Checkmate: 将 擒 (canggim)

A canggi move: 手 (ka)

Fourfold repetition: 輪回手 (runhwaisyu)/삼사라手 (samsarasyu, from Sanskrit संसार, saṃsāra)

Perpetual check (fourfold repetition caused by consecutive checks): 連續将軍두輪回手 (renzok cangkun tu runhwaisyu)

Screen (the piece that the arrow/cannon jumps over): 臺 (dai) [Note: 臺 is specifically the word for the cannon’s screen but it’s also used to collectively refer to both. For the arrow’s screen specifically, the word 弓 (nan) is used]

The game ends when a player is checkmated, has resigned, or a draw has been agreed. A game is drawn when there is fourfold repetition or when both players agree that it is no longer possible to mate each other’s general. The exception to fourfold repetition is that it is against the rules to cause such a repetition through consecutive checks.

Should a player be left with no legal moves, yet it is their turn to play, the player is then obliged to pass their turn. In no other circumstance may a player choose to pass their move. The player indicates passing their turn by taking their general, flipping it 180 degrees, and placing it back down on the square. The general is marked “將” on both sides for this purpose.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cantonese loanword types

Extract of a conversation I was having with someone on Cantonese loanword types:

Friend: Are english loans in cantonese commonly assimilated to cantonese phonology? To what extent?

Me:

I think there are 3 levels

1. non-lexicalized

2. semi-lexicalized

3. fully lexicalized

fully lexicalized are words that have dedicated hanzi, I'd say perhaps the first is like code-switching. The second type are words that have a standardized pronunciation that fits almost perfectly if not fully perfectly into Cantonese phonology, but without hanzi

1. ? [nothing came to mind then]

2. haai1 lai1 taa*2 (highlighter)

3. 的士 (taxi)

It's hard to place sometimes. For example the word pro6 (/pʰɹou˨˨/ ”professional”). Technically canto of course doesn't have /r/, so it's not easy to judge whether this is a case of code-switching or semi-lexicalized.

哇,你好pro呀!

"wow, you're very professional!"

It's been noted (Multiple scansions in loanword phonology, Silverman, 1992) that [the last syllable of] Cantonese loanwords have a tendency to receive the 變音 (tone 1 or 2). I think this can be a way to classify type 2 or 3. By this standard, pro6, which doesn't use tone 1 or 2, would fit into group 1, which also makes sense since /r/ isn't in native Canto phonology.

[...]

there is a structure:

stressed syllables use tone 1

unstressed syllables use tone 4

epenthetic syllables use tone 6

final syllable uses 變音

or at least, this was what was documented in [Silverman’s paper], but I think these days tones 4 and 6 would be interchangeable

[For the case of “pro”], it uses tone 6 for an unstressed syllable (and not tone 4).

#cantonese#cantonese loanwords#phonology#cantonese phonology#loanwords#loanword#linguistics#rangyayo#rangyan

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

曉匣 as glottal?

I am starting to doubt my designation of LMC (and also EMC) 曉匣 as /x ɣ/ and am starting to lean more towards /h ɦ/, because of the group 精清從心邪 being put together, if 曉匣 was actually velar, I'd have expected them to be grouped with the velar 見溪群疑, but they are instead put after 影喻 as “throat sounds” (喉音) in the rime tables.

I had thought of representing 曉匣 as /x ɣ/ and 喻 as /ɦ/ to prevent the clumsy (and probably implausible) designation of /ɣ₂/ for 喻. However, in light of 曉匣 being probably /h ɦ/, this may not necessarily be a great designation. And considering 影 is ∅~/ʔ/, I am starting to see why a laryngeal consonant /ʜ/ is designated for 喻 by some (though /ʜ/ is a trill and a fricative /ʔ̞/ or more simply /ʕ/ would probably have been more suited), as there is no “voiced glottal stop”. However, I am still more inclined to assign 影 as a null initial and only use /ʔ/ for categorical purposes.

1 note

·

View note

Text

析韻輸入法 (ParseRime IME)

苑安雄’s 析韻輸入法 (previously “切韻輸入法”), or in English, “PRime” (standing for ParseRime IME) is a pan-Chinese topolectal diaphonemic/Late Middle Chinese-based input method. Basing primarily on modern pronunciations and distinctions up to rime groups (攝), the input method can be learnt without having to memorize the intricate rimes of MC, relying more on the shared diaphonemic distinctions of the modern Chinese varieties.

Each character can be inputted with just a maximum of 4 keystrokes (initial + medial + tone + rime group), making it as fast as Cangjie but without the complexities of having to learn what character parts each key has to stand for, that gives Cangjie its steep learning curve to beginners. Those who are familiar with pan-topolectal Chinese distinctions/Late Middle Chinese would likely find themselves at relative ease when it comes to determining the input codes for any given character they know the pronunciations for.

The use of the dedicated shift key for voicing distinction meant that all the 36 LMC initials can be fit into the 26-key QWERTY keyboard, and there are some fuzzy matches allowed (e.g. where the modern varieties do not have a direct correspondence to the character’s LMC pronunciation), such as typing 非 for characters that traditionally have the 敷 initial.

The input method is currently available for users of RIME (Win/Mac) and TRIME (Android).

You can find more information about the IME (including a user guide and an input code dictionary) and keep up with potential updates on these links:

- PRime on the Chinese Forums

- PRime on Sheik’s Cantonese Forums

- PRime page on TCC (legacy version): An old post I had written about this IME, though some of the links are now dead.

- PRime small guide on TCC

Information on an older version of PRime can be found on my blog here.

Picture credits go to 苑安雄.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Cantonese variant tone: a tonal suffix

While working on my Masters’ thesis, I had the opportunity to read Silverman’s 1992 paper on Cantonese loanwords, “Multiple scansions in loanword phonology: evidence from Cantonese“. The paper made a finding that in many of the older Cantonese loanwords, the “variant/changed tone” (變音; LSHK: bin3 jam1; Ball: pín꜄ ꜀yam) phenomenon occurs with loanwords from English. An example would be 的士 being pronounced dik1 si*2, with the variant tone instead of the modal pronunciation of “dik1 si6″ (which would otherwise follow tonal rules of loanwords, where epenthetic and unstressed syllables carry low tones*). The variant tone, according to Chao, is also used to distinguish general objects from familiar objects, such as general smoke (jin1) vs cigarette smoke (jin*1).

Silverman mentioned that the variant tone could be summarized into being a morphemic tonal suffix [˥] which attaches itself to the original tone the syllable carries.

This explains how the variant tone for modal tones 4, 5, 6 become phonetically identical to tone 2 on the surface, while the variant tone for modal tone 1 becomes high level. The reason for this is smoothening.

If you consider the starting point of tones 4, 5, 6, they all start low, and after attaching the high tonal suffix, get smoothened to a plain low to high contour tone (i.e. the same as tone 2):

Tone 4 smoothening: [˨˩ + ˥] > [˨˩˥] > [˨˥] > [˦˥]

Tone 5 smoothening: [˩˧ + ˥] > [˩˧˥] > [˩˥] > [˦˥]

As for tone 1, for a lot of speakers today, the high level and high falling tones are no longer distinguished, so it would be hard for speakers of such accents to remember which tone 1 used to be which. However, from this rule, it could be deduced that high falling is the modal tone 1, and that high level is the variant tone 1, because:

Tone 1 smoothening: [˥˧ + ˥] > [˥˧˥] > [˥˥]

Thus, for those interested in studying historical Cantonese phonology, this could be a useful way to remember which tone is which.

Of course, the big takeaway here is that the variant tone could be interpreted as being a tonal suffix [˥].

*: This refers to the 陽 tones, and not Silverman's L tone. The reasoning behind my rejection of Silverman's 3-height tonal classification is because for many speakers, there are 4 level tones, and thus Silverman's 3-level tonal classification is not sufficient in representing all of the Cantonese tones accurately.

17 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Triungku Haanngyu Szshieng

Middle Chinese art design by myself (Tangent Ghwaang): The 4 tonal classes of Middle Chinese

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I noticed how the Japanese …てある and …ている forms can be compared to the constructions of have/be + verb in English, even if their usages don’t overlap always.

You see …ている showing continuous action (similar to the English counterpart) and …てある showing a perfective aspect of whether you have the experience of doing something (also similar to English sentences “I have swum [before]”) and Sinitic constructions like “我有游過水“ mentioned in this post.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

So I was reading a book about MC rimes and I came across Branner’s transcription for Middle Chinese:

失占切

Baxter (1992): syit + tsyem = syem

Branner (1999): {syet₃ᵦ} + {tsyam₃ᵦ} = syam₃ᵦ

At first I thought, wait, there are extra numbers and letters at the end? That’s more cumbersome! But then I thought, actually this is a more neutral transcription because unlike Baxter’s transcription, it doesn’t try to posit what the values of those rimes are, simply designating them based on shiep (攝) its subclasses, so I see what they’re trying to do and it truly manages to be a “pure” transcription without projecting guesses of the values as much onto the rimes.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

(extract of a conversation regarding orthography and linguistics I was having with others)

One of the people who study language I really admire is Champollion.

And more recently there was a breakthrough with deciphering Mayan orthography.

But I don’t think modern linguistics really have a field for these collective studying of orthography because they just don’t care about writing.

A lot of stuff that linguists don’t care about are simply stuff they don’t find worth it to study, and imo it doesn’t mean that thing actually isn’t worth studying. New fields thus pop up and its pioneers have had to convince the linguistic world to care. The more recent field of linguistic prosody pioneered by Arvaniti for instance, I think, would be an example of things that were previously not regarded as important.

It is actually really ironic because linguists don’t like concerning themselves with writing but anything in history prior to writing is lost so as much as they don’t think writing is something that deserves linguistics studying on, writing had been all they can rely on for historical evidence.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

So I was talking to someone about English words carrying a meaning of success vs the Chinese lack of it

First case we discussed was “找” vs English “find”

Cause in Mandarin you could say 我一直找他,但是找不到

a lot of students I’m looking at mistakenly used the word “find” and wrote

I keep finding him, but I can’t find him

of course in this case the solution is to simply use “look for” for the former

but my Chinese syntax professor brought up the word 殺 in Chinese vs the English “kill”

Again in English it implies a success at causing death, but in Mandarin you could say 他殺他不死

and apparently in English you can’t say something like “he killed him, but he survived” as that would be a contradiction

49 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Willow Pattern Craft

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vernacularized TCC (provisional)

“Vernacularized TCC” is my provisional name for a loose TCC spelling convention I use. It is primarily used for character names or concept names/loanwords in fiction. One could consider it a collection of related, historically-motivated Sinitic conlangs. It is somewhat of a hybrid between the basic TCC and Modernized TCC, but without being a rigid system like the former two, instead being a more versitile representation, but one that includes more mergers than the systems. Like the previous systems, Vernacularized TCC focuses on aesthetic realism (but even moreso than them), something that “looks Chinese” to someone unfamiliar with Chinese. As a result, “un-Chinese” clusters used in TCC such as “gh” and “ds” will not be used here. Simplicity is also championed, so merging “ing” with “ieng” into “ing” might be considered. The spelling convention is similar to Modernized TCC but with “o” being replaced by “a”.

Besides names, VTCC may also be used when imitating a descriptive foreign text where aspiration markings and other diacritics are left out (like in a passage by ancient travellers speaking of “chi” [氣]), essentially resulting in a postal romanization.

Some variations may be considered depending on the time period and precision the writer desires. For example, employing the voiced set of obstruents to signify a more historical time period. Variations may also be considered should 2 characters be from different Chinese backgrounds (e.g. perhaps one of the characters come from a place where voiced obstruents are used [cf. Modern Wu or Middle Chinese], and another comes from where the retroflex stop series are pronounced as alveolar stops [cf. Modern Min]).

Tones are generally omitted and multi-syllabic names may be combined into one word or not at the writer’s descretion.

Below are rough guides for spelling in VTCC:

1. Aspiration is usually omitted, but if really desired, an h or aspiration mark may be used.

2. Voiced obstruents may be omitted. The use of gh is discouraged.

3. Implied merging of /dz~z/, and, more often, /dʑ~ʑ~dʐ~ʐ/. If desired, the /dz~z/ distinction may be kept while employing the latter merger.

4. “gn” is not often used in Chinese Romanization and may be discouraged for aesthetic purposes unless specifically going for e.g. Hakka-based styles. “nh” is also discouraged. “j” assumes the pronunciation /ʑ~ʐ/.

5. The diacritic in the â of basic TCC is omitted, merging the spelling with Div II. While the diacritic in ê is also omitted, this usually produces no spelling mergers, as Div III e usually follows i or ü.

6. z rather than i is encouraged after ts, and ze may be used after s. Thus, tsz, sz(e).

7. ü may be the only letter that carries a diacritic in VTCC. Or it can be omitted too, or replaced with iu. As a medial, iu~yw may be used in place of ü~yü~u~yu.

12 notes

·

View notes