Text

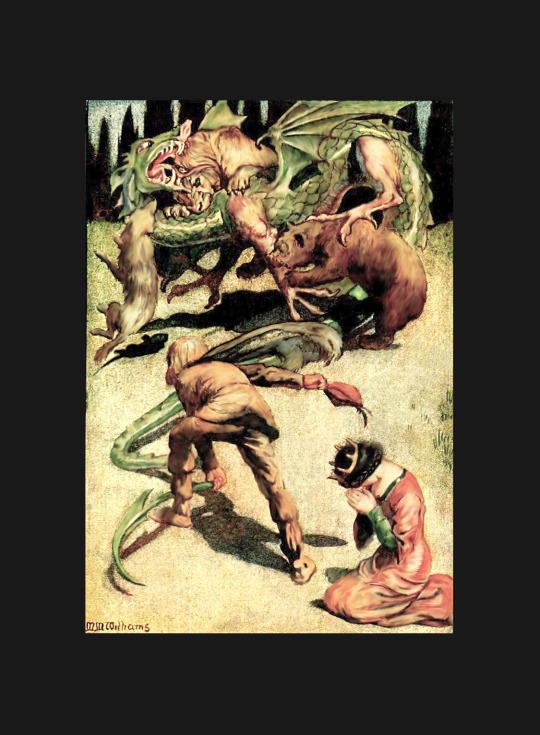

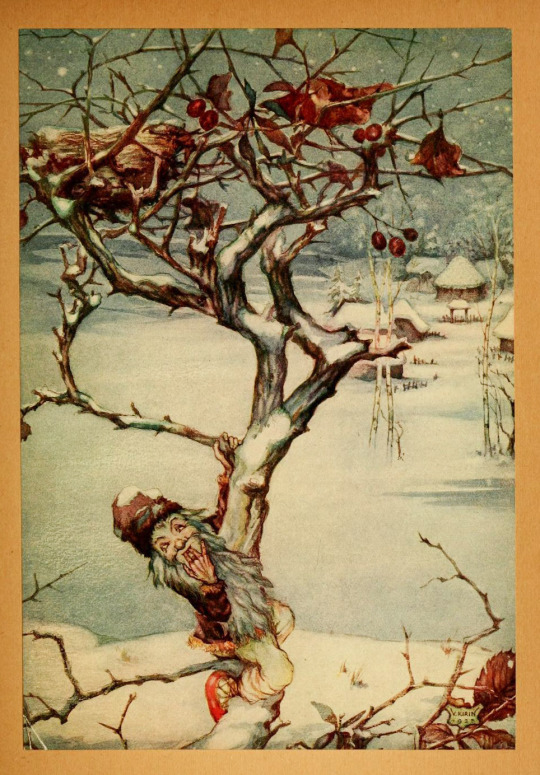

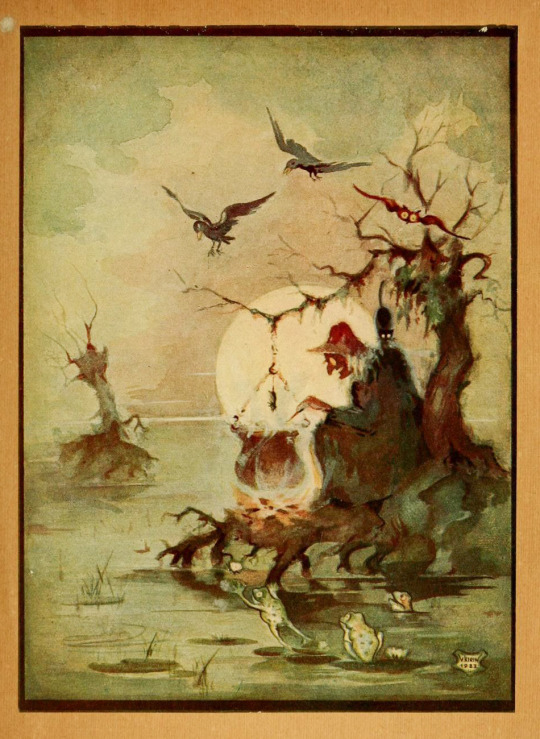

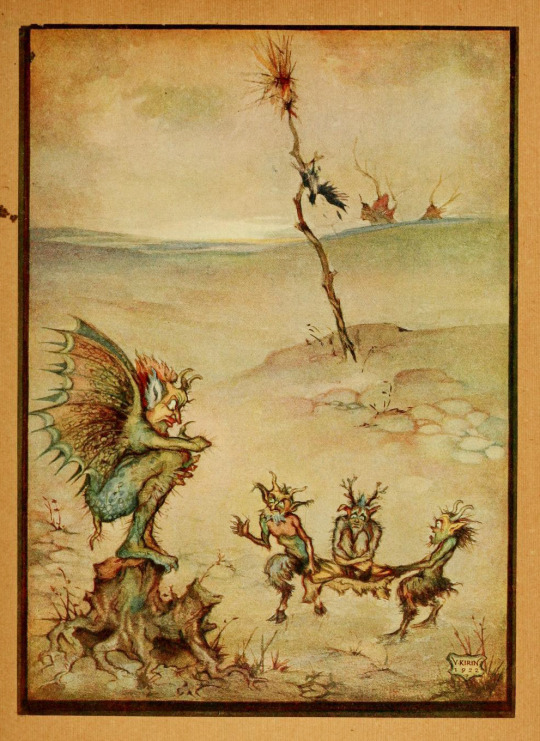

CROATIAN TALES OF LONG AGO by Iv. Berlić-Mažuranić. (New York: Stokes, 1922). Cover art by M.M. Williams. Illustrated by Vladimir Kirin. Translated by F.S. Copeland.

source

#beautiful books#book blog#books books books#book cover#books#vintage books#illustrated book#children’s book#book design#croatia#folk tales#m.m. williams#vladimir kirin#iv. berlic mazuranic

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

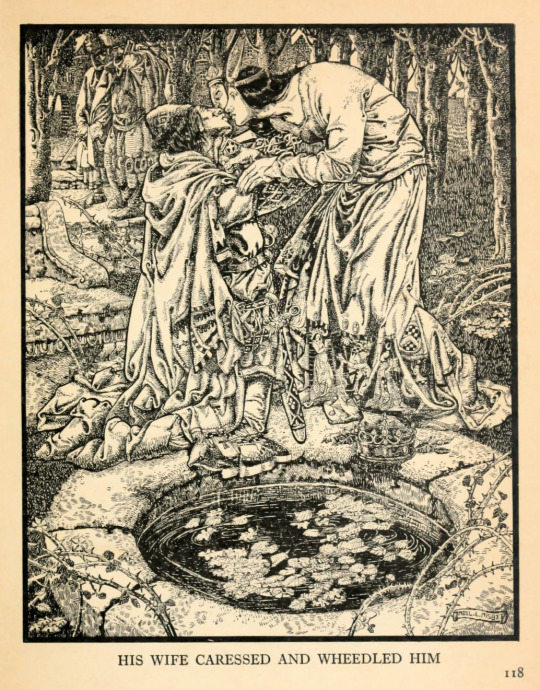

COSSACK FAIRY TALES AND FOLK TALES edited by R. Nisbet Bain (London: Harrap, 1916). Illustrated by Noel L. Nisbet.

source

#beautiful books#book blog#books books books#book cover#books#vintage books#illustrated book#children’s book#book design#czechoslovakia#fairy tales#folk tales#r. nisbet bain

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

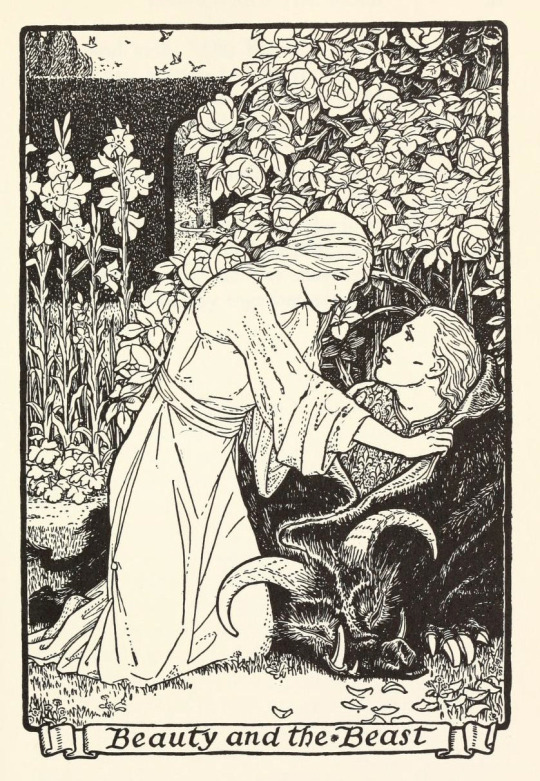

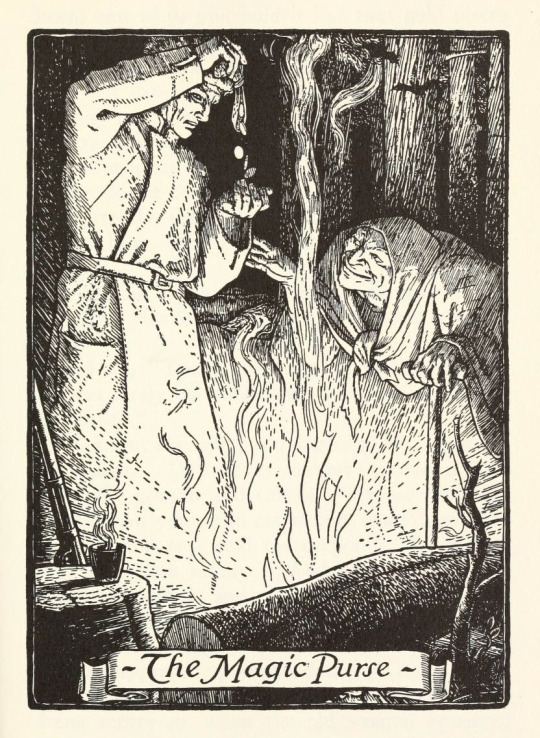

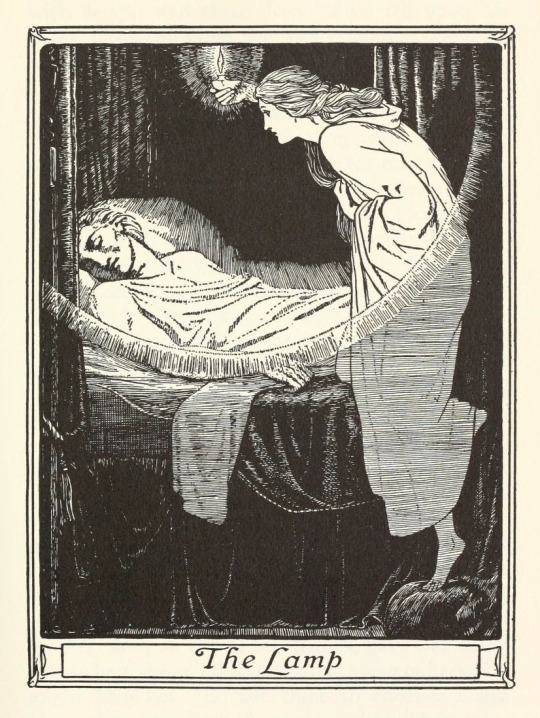

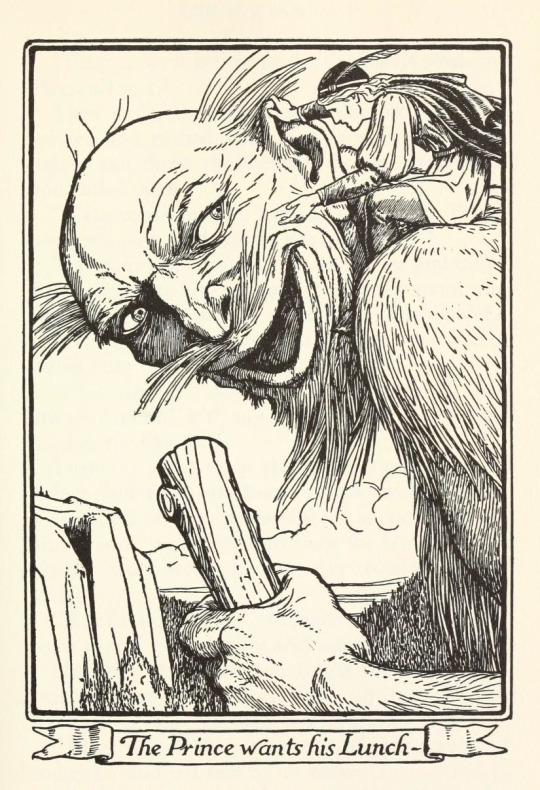

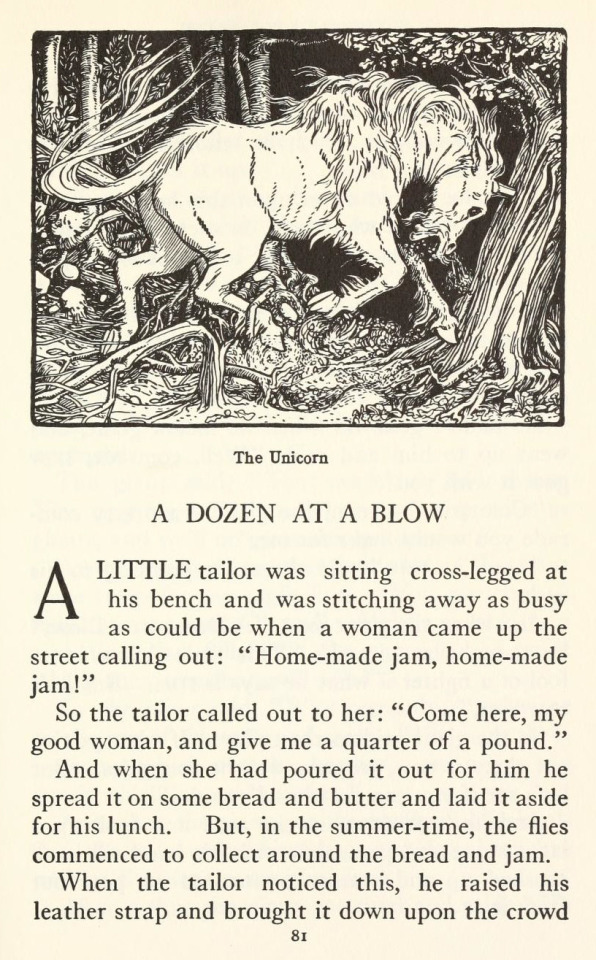

EUROPEAN FOLK AND FAIRY TALES edited by Joseph Jacobs. (New York: Putnam, c.1916) Illustrated by John Dickson Batten.

source

#beautiful books#book blog#books books books#book cover#books#vintage books#illustrated book#children’s book#book design#fairy tales#joseph jacobs#john dickson batten#beauty and the beast#the magic purse#the lamp

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

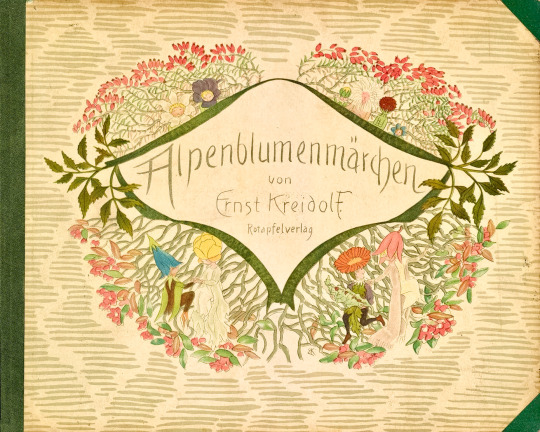

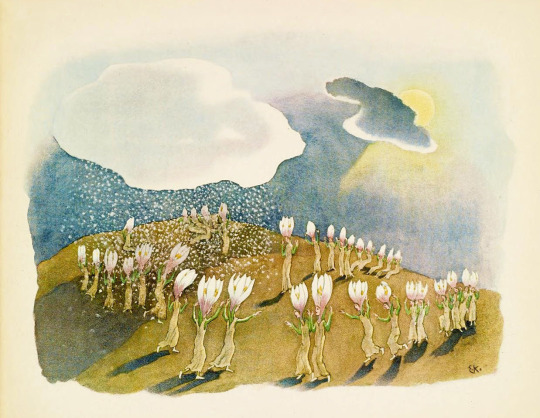

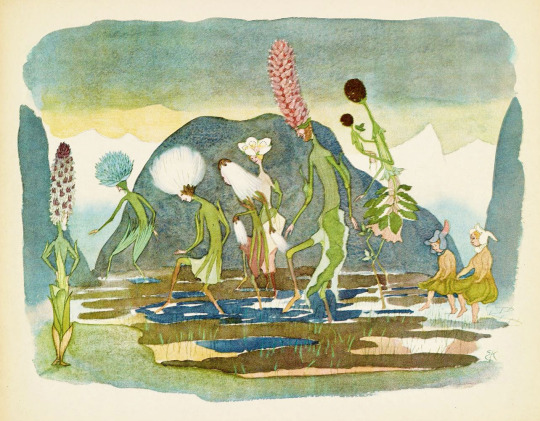

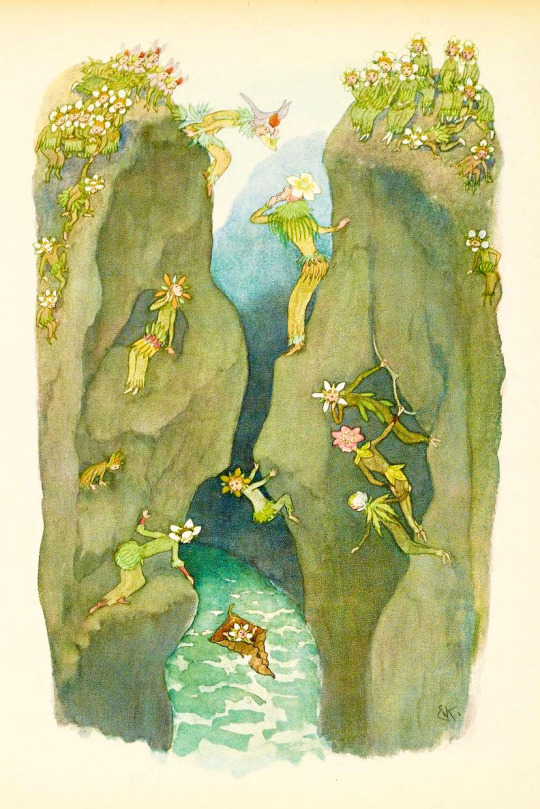

ALPENBLUMENMÄRCHEN [aka ALPINE FLOWERS FAIRY TALE] written and illustrated by Ernst Kreidolf (Erlenbach-Zürich: Rotapfelverlag, 1922)

source

#beautiful books#book blog#books books books#book cover#books#vintage books#illustrated book#children’s book#book design#fairy tales

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

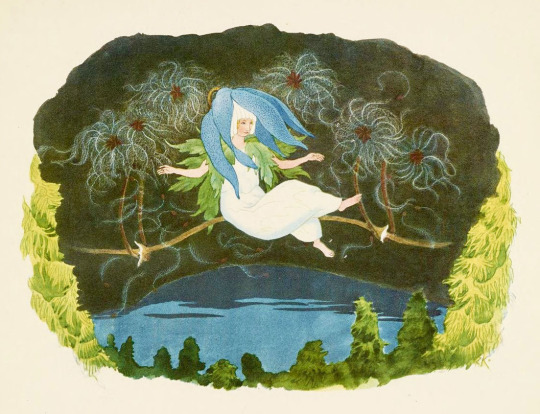

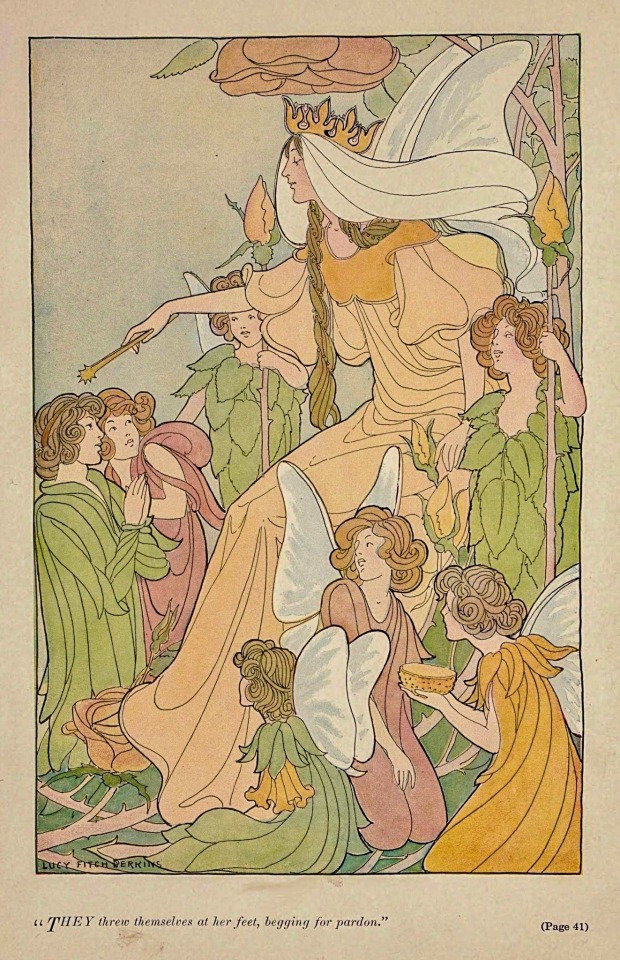

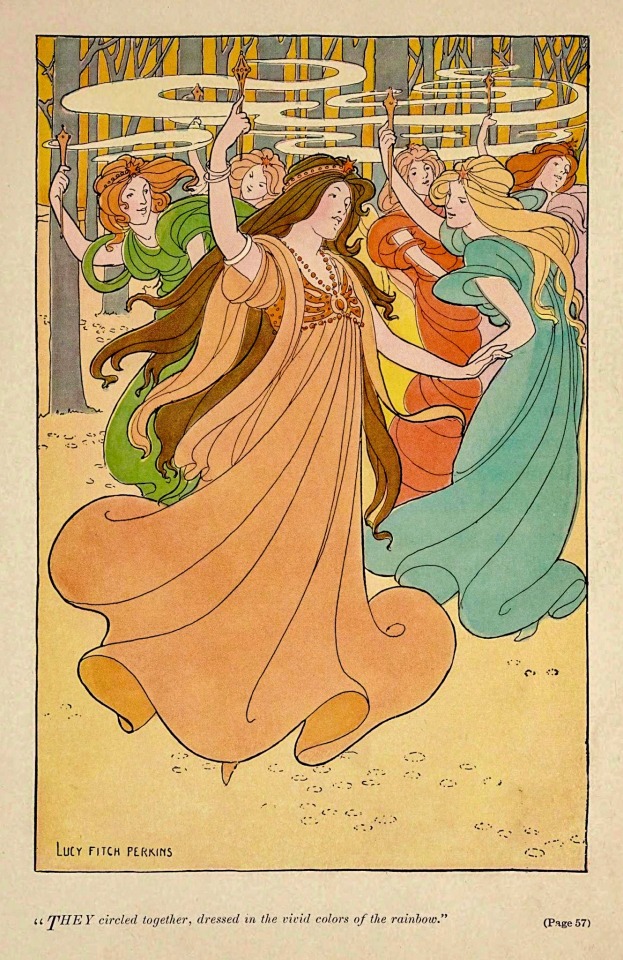

THE MOON PRINCESS: A Fairy Tale by Edith Ogden Harrison. (Chicago: McClurg, 1905) Illustrated by Lucy Fitch Perkins.

source

#beautiful books#book blog#books books books#book cover#books#vintage books#illustrated book#children’s book#book design#fairy tales#lucy fitch perkins#edith ogden harrison

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

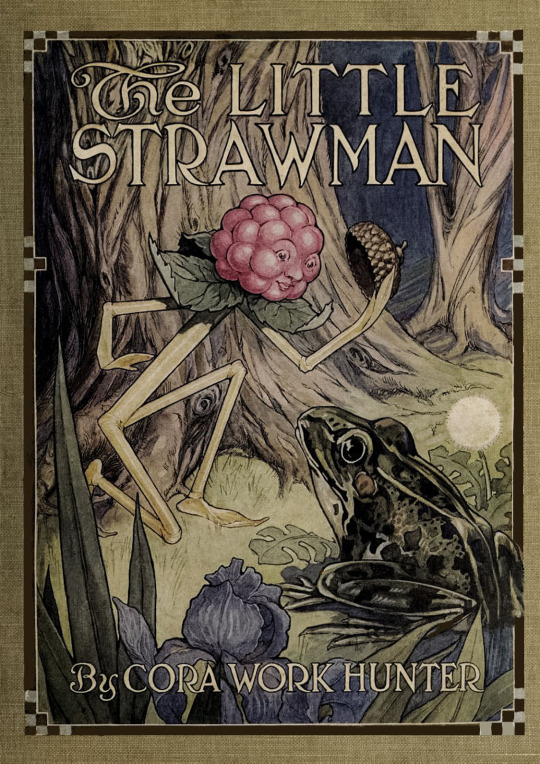

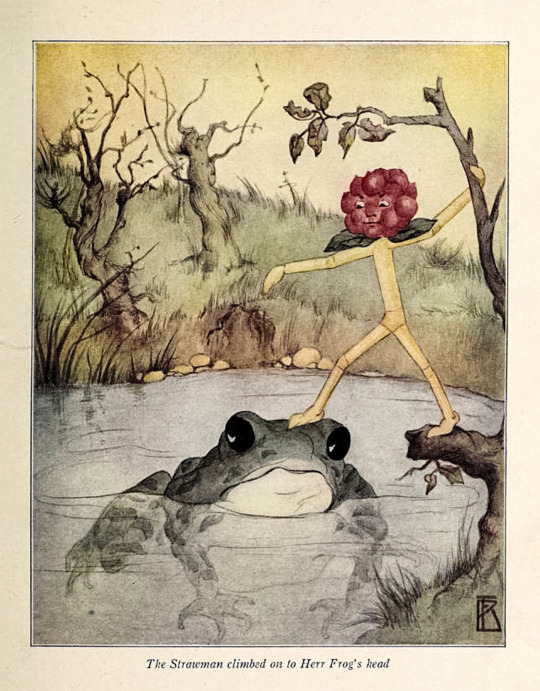

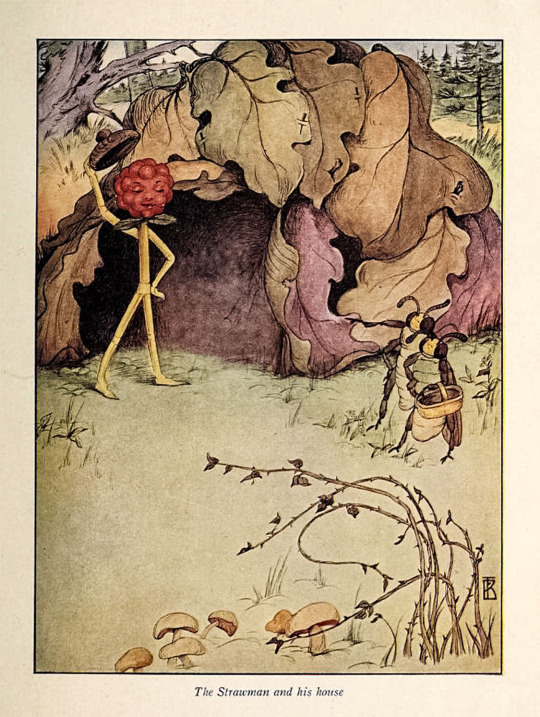

THE LITTLE STRAWMAN by Cora Work Hunter (Chicago/New York: Rand McNally, 1914).

source

#beautiful books#book blog#books books books#book cover#books#vintage books#illustrated book#children’s book#book design#cora work hunter#fable

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

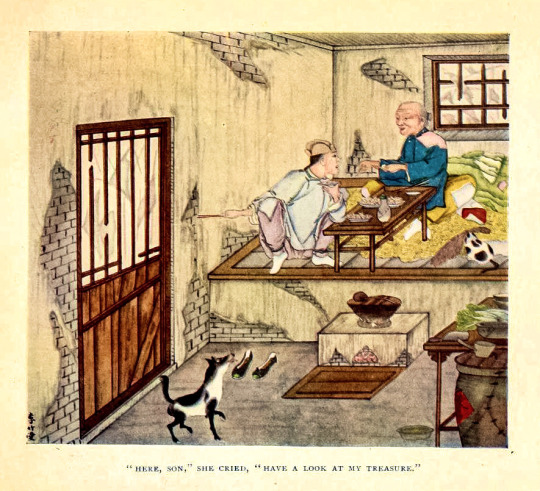

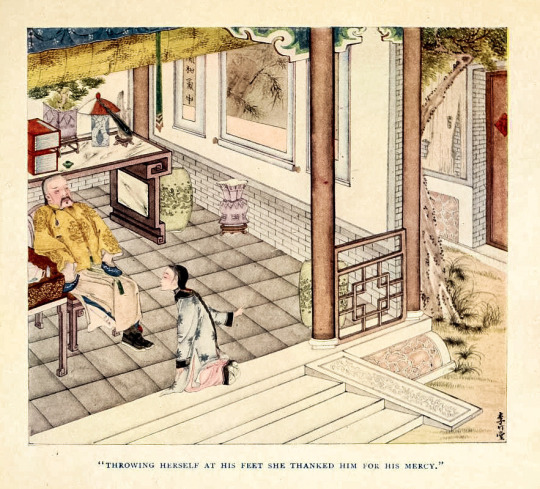

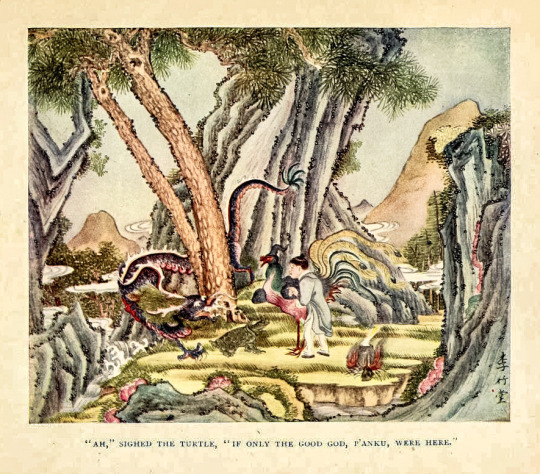

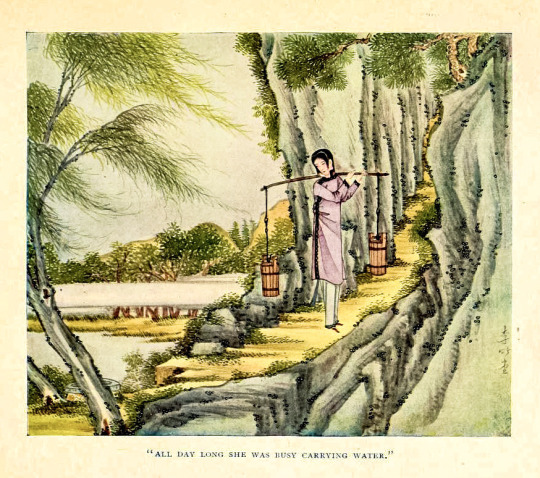

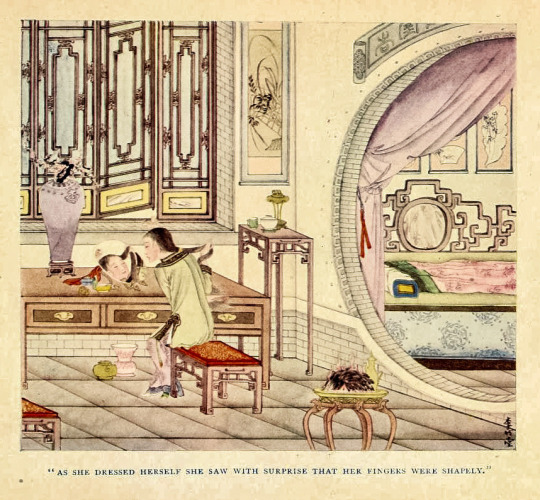

CHINESE WONDER BOOK edited by Norman Hinsdale Pitman (New York: Dutton, c.1919) Illustrated by Zhutang Li.

source

#beautiful books#book blog#books books books#book cover#books#vintage books#illustrated book#children’s book#book design#fairy tales#chinese folklore#norman hinsdale pitman#zhutang li

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

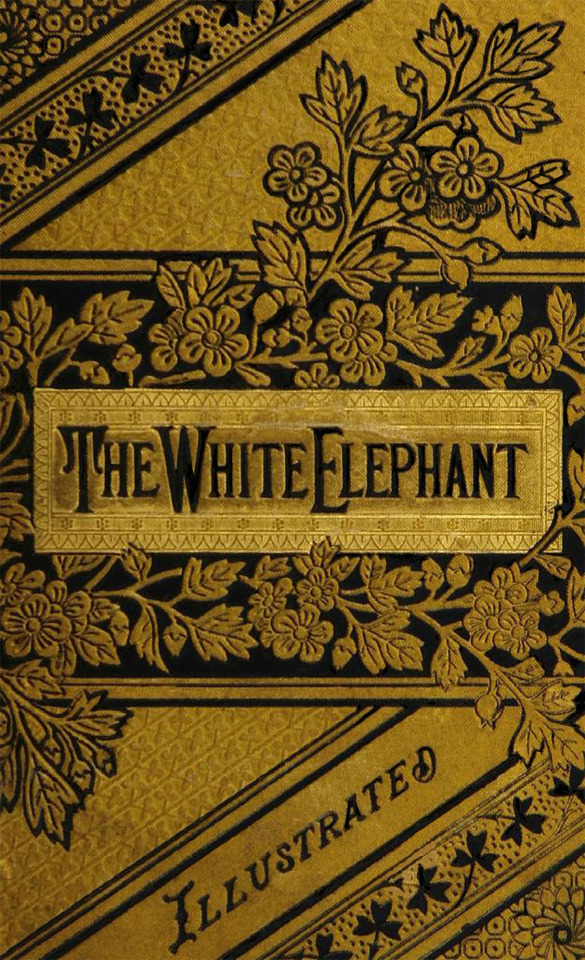

THE WHITE ELEPHANT; or, The Hunters of Ava and the King of the Golden Foot by William Dalton. (New York: Lovell, 1881). Illustrated by Harrison Weir.

source

#beautiful books#book blog#books books books#book cover#books#vintage books#illustrated book#book design#william dalton#harrison weir

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

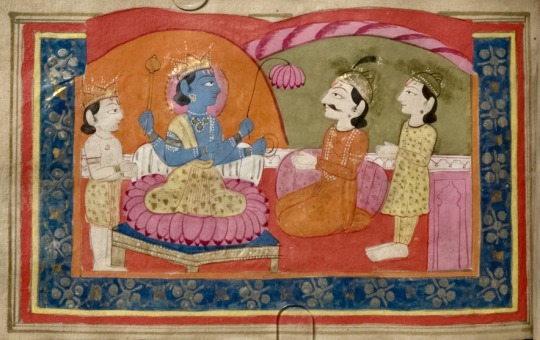

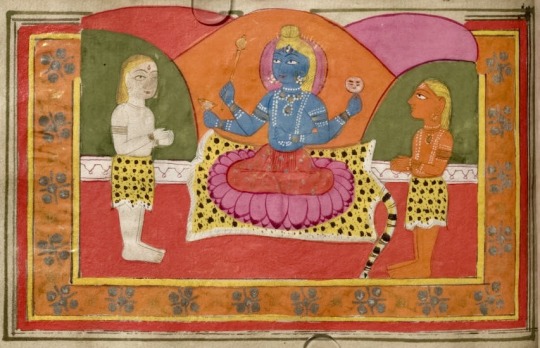

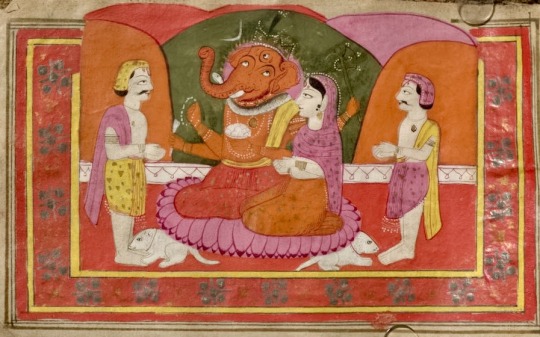

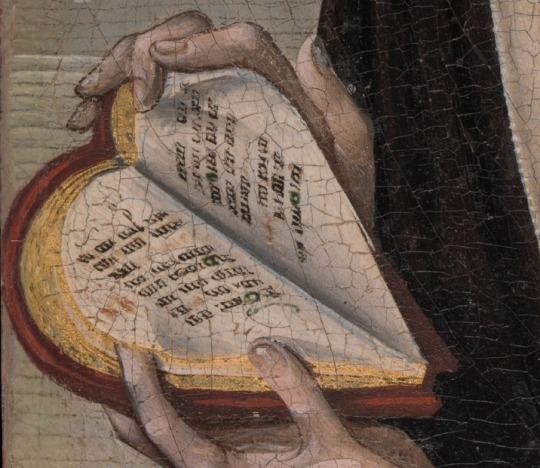

STORIES OF HINDU GODS (India: 1720)

Includes 9 full-pages of painted miniatures, showing Persian influence although the manuscript is probably of Indian origin.

source

#beautiful books#book blog#books books books#book cover#books#old books#book design#hindu mythology#sanskrit#india#ganesha

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE WHITE ELEPHANT by Charles Reade (New York: Gibson & King, [c.1884]]

source

#beautiful books#book blog#books books books#book cover#books#vintage books#book design#charles reade

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

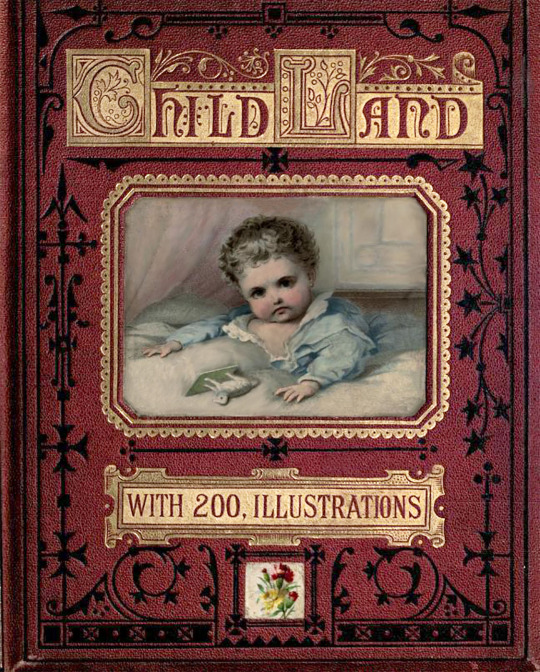

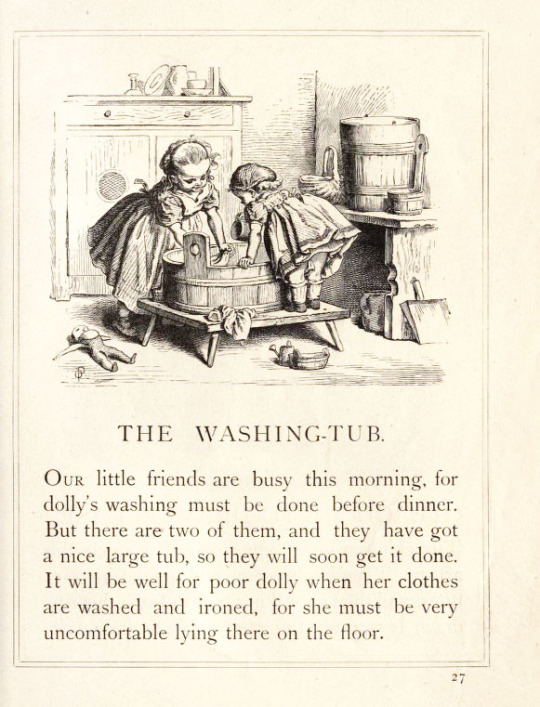

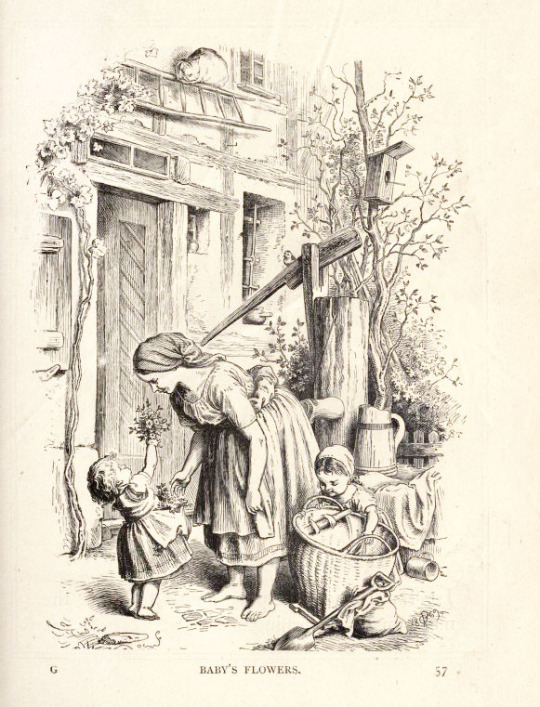

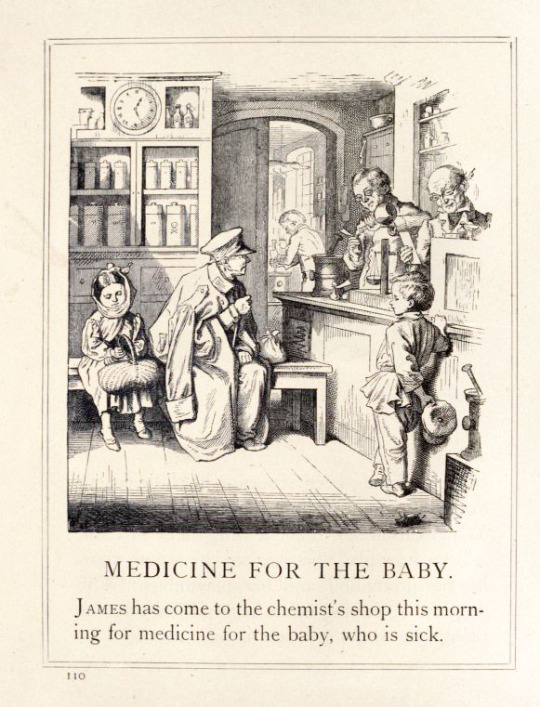

CHILD-LAND: picture pages for the little ones by Oscar Pletsch. (London: Partridge, [1873]). Gift book containing 200 designs by Oscar Pletsch, M. Richter, et al.

source

#beautiful books#book blog#books books books#book cover#books#vintage books#illustrated book#children’s book#book design#victorian era

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

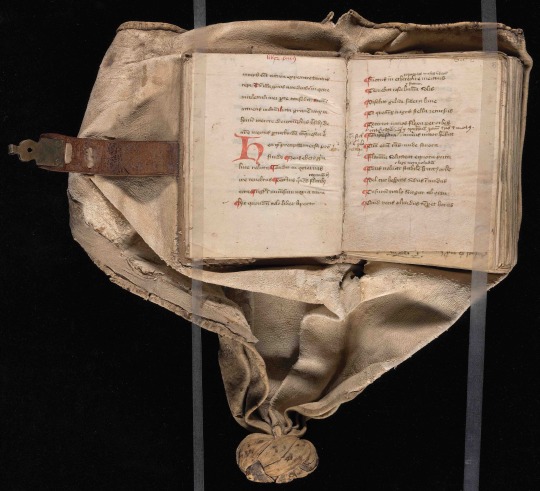

Medieval book transport

You are looking at two ‘wraps’ (top), the outside and inside of a box (middle), and a leather satchel (bottom). What they share is not just their old age (they are all medieval), but also the purpose for which they were made: to transport a book from A to B. The actual reason for transporting books in these objects varied considerably. The wraps are late-medieval girdle books, which were hanged from the owner’s belt by the knot. The text inside - which was often of legal or religious nature - could be consulted quickly and easily: just unwrap it and read. The box (and the ninth-century book inside) had a more exotic use: the package functioned as a charm for good luck on the battlefield, where it was carried in front of the troops by a monk. The satchel, which also dates from the ninth century, was just a bag to transport a book while on the go - it was popular among monks. Read more about these fascinating devices in my blog post “Medieval Books on the Go” (here).

Pics - Wrap at top: Stockholm, Royal Library (16th century, source); Wrap below it: Yale, Beinecke Library, MS 84 (15th century, source); Box: Dublin, Royal, Irish Academy, D ii 3 (8th/9th century, source); Satchel: Dublin, Trinity, College, MS 52 (Book of Armagh, 9th century, source).

5K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Dreamy eyes

Heart-shaped books from medieval times frequently make their rounds on social media (here is a really nice post devoted to them). For good reason, of course, because they are as unusual as they are pretty. Dating exclusively from the 15th and 16th century, they commonly contain songs, poetry and other short texts devoted to Love. As much as I love actual surviving books, this depiction in a painting from c. 1480 speaks to me because of the context it provides - lacking when you hold the real medieval book in your hand. There he is, the reader, walking around town, holding the heart-shaped pages with love poetry in his hand. He looks dreamy, as if contemplating his love, lost or waiting at home. It’s an unusual snapshot of how those heart-shaped books were used for real - or at least how I would like them to be.

Pic: Metropolitan Museum, Accession nr. 50.145.25 (Young Man Holding a Book, anonymous, c. 1480). More info here, as well as a Hi-Res image.

#books#medieval#bookhistory#beautiful books#book blog#books books books#book cover#book design#rare books#book of hours

942 notes

·

View notes

Text

BOOK OF HOURS for use in Rome. (France, c.1555) A liturgy in Latin made c. 1555 for King Henry II of France.

The pages of this Book of Hours appropriately resemble Fleurs-de-Lis, a symbol for French royalty. It was made for King Henry II of France contained prayers and other short texts, which were read at set times during the day. Not only does the very shape of the pages testify to the object’s royal patron, so too does the high quality of the decoration. The manuscript measures only 182×80 mm and has 129 leaves.

‘Written by hand, medieval manuscripts are very different from printed books, which started to appear after Gutenberg’s mid-fifteenth-century invention of moving type. One difference in particular is important for our understanding of manuscripts. While printed books were produced in batches of a thousand or more, handwritten copies were made one at the time. In fact, medieval books, especially those made commercially, came to be after a detailed conversation between scribe and reader, a talk that covered all aspects of the manuscript’s production. This is the only way the scribe could ensure the expensive product he was about to make was in sync with what the reader wanted. Consequently, while printed books were shaped generically and according to the printer’s perception of what the (anonymous) “market” preferred, the medieval scribe designed a book according to the explicit instructions of its user. ’—Erik Kwakkel on medievalbooks.nl (2014)

source

source [digital reproduction]

#beautiful books#book blog#books books books#book cover#books#illustrated book#book design#book of hours#king henry ii#16th century#illuminated#fleur de lis#bookbinding#christian bible#worship#fleur-de-lis#old books#medieval

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

FLEUR DE LYS-SHAPED BOOK OF HOURS, in Latin, use of Rome (Paris, c. 1553). Illuminated manuscript on paper.

180 x 80mm. i + 117 leaves, each page with 24 lines written in a 'roman' hand in black ink within a liquid gold border in the shape of a half fleur de lys, spaces infilled with liquid gold fronds on blue or red grounds, line-fillers and one- and two-line initials of the same colours, eleven lobe-shaped miniatures. Nineteenth-century brown morocco gilt, semé with fleur de lys, doublures of red morocco gilt, edges gauffered and gilt (upper cover detached). [Christies Auction House, 2006 catalog]

source

#beautiful books#book blog#books books books#book cover#books#shaped book#fleur de lis#book of hours#latin language#treasure book#book design#book binding#old books

562 notes

·

View notes

Text

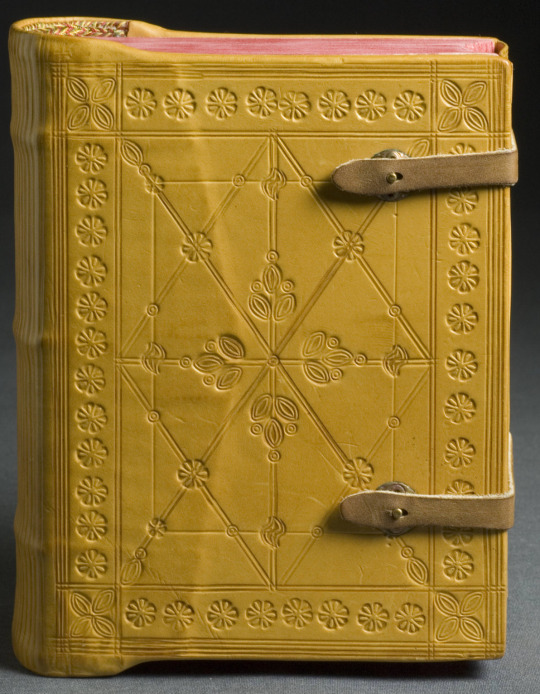

17th Century Armenian book cover. Tooled leather.

#beautiful books#book blog#books books books#book cover#books#book design#17th century#armenian#book binding

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

The silver cover of this manuscript was commissioned in 1675 by Minas Vardapet. The silversmith was Khachatourian Yakop in Tokat.

#beautiful books#book blog#books books books#book cover#books#book design#book binding#armenian#silver#christian bible#17th century#treasure binding#bookbinding

24 notes

·

View notes