Text

"Some Old Norse sources also indicate that Óðinn may be reached by travelling down through water (Heide 2011: 67–68); some place names and cult places indicate the same thing. The small lake Odensjön in Scania, named after Óðinn, if indeed the name is ancient*, is one example. The water of the lake is gathered in a circular, crater-like hole in the flat landscape; the lake lacks inflows, and in old times it was believed to be bottomless (Nordisk familjebok 1888: 101). This has a similar character to the north Sami sáiva ponds (cf., e.g., Pakasaivo in northern Finland), which are typically small and without inflow, believed to be bottomless and containing passageways to another pond rather than the visible one (Wiklund 1916, Bäckman 1975, Mebius 2003: 82). There is reason to believe that this passage was considered in the past to be a link to the otherworld – the noaidis (Sami shamans) most often used the guise of a fish as transport when they went to the land of the dead; they were said to ‘dive’ when going there (Olsen 1910 [Etter 1715]: 45, cf. 46; Heide 2006: 232–33), and in southern Sami regions, sáiva – in the form saavje (aajmoe) – means ‘ancestral mountain’ of a similar type to the Old Icelandic Helgafell (Eyrbyggja saga: 19, Landnámabók: 125) and Kaldbakshorn (Njáls saga: 46).

Judging from its name and from the examples of the sáiva ponds, there is reason to believe that Odensjön was imagined to be a passageway to Óðinn / Valhǫll. The argument is corroborated by sáiva / saajve being to all appearances a loan from Proto-Scandinavian saiwa-R ‘lake’ (the etymological ancestor of sea / sjö / See; Weisweiler 1940), which indicates that the ideas of such water passageways existed in old Germanic tradition. This is confusing in that one is able to travel through water to a mountain visible on earth, but this is also the case in Eyrbyggja saga and Njáls saga: both Þorsteinn Þorskabítr and Svanr of Svanshóll drown before they can enter the mountain."

-Eldar Heide, from "Contradictory cosmology in old norse myth and

religion – but still a system?"

*Stig isaksson (1958: 29) believes that the name Odensjön is a learned invention from the early modern age, but if so, we ought to have heard of an older name. We have not, and Isaksson does not seem to have conclusive arguments. His strongest is that d- in Oden- is pronounced, while it is not in Scanian legends about Odin (Odens jakt). But there are many examples of peculiarities in the pronunciation of place names, and very many have had their pronunciation influenced by writing, without being for this reason learned constructions. There are many examples that an inter-vowel d because of spelling pronunciation is pronounced in ancient names (e.g. Eide in numerous places in Norway), in dialects that normally skip the d in this position.

117 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“ Summer in North of Norway “ // Max Rive

661 notes

·

View notes

Text

Things that make me want to tear up: gifting the dead.

To think that multiple communities across the world accepted the finality of Death and yet still proceeded to gift the deceased with expensive, handmade, or rare objects in memoriam is something that hits me with the sense of love for humanity. There’s no reward in gifting the dead. There’s nothing to pursue. There’s just a sense of immense affection and love; be safe to the grave and beyond, my joy. Here, take it with you for the safe travels.

623 notes

·

View notes

Note

This post made me think of you https://www.tumblr.com/wanderingwitchofthewood/689523423060361216

well, it's not entirely wrong - but I would rephrase the sentiment: do come to me for advice.

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

My goal in life is to be the person running the bookstore in the horror thriller where the protagonist has to go to track down a rune. I've got stupid hair and a vest or something. The protagonist shows me a rune drawn on a napkin and I say shit like "Aha! Just a moment!" Before skittering off for some gay ass book

38K notes

·

View notes

Text

Huginn, Muninn, let’s blow this popsicle stand

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

date a forest god who can identify any animal or plant instantly just by seeing or holding it, even if it’s only a tiny part

156 notes

·

View notes

Note

What's the difference, if any, between fylgja and hamingja?

I'm still a little messed up in the head from a cold but I'm gonna take a crack at this, just be advised that there's really no way to summarize this in a blog post no matter my cognitive state so I'll just try to get you started by focusing on the problems of differentiation in the border between the two concepts. I'm going to draw heavily from Zuzana Stankovitsova's MA thesis on fylgjur, and if you want to understand the depiction of fylgjur in the sagas I highly recommend you read the whole thing.

This is kind of a constantly ongoing discussion. The problem isn't that there isn't a discernible difference, it's that each one is internally inconsistent, and within those spans of inconsistency, there's some overlap. So you get instances of fylgjur and hamingjur that seem to have hardly anything to do with each other, but then also separately instances of things called fylgja that you'd have expected to be called hamingja, etc. This honestly is very common in Norse literature generally. We expect consistent, distinctive, taxonomic categories but you can't do a DNA test on a norn or an isotope analysis on a dís's fossilized skeleton. But with fylgja the fuzziness might be a little above average even for Norse concepts. It also probably changed over time, within the span of time documented in the sagas.

The crux of the confusion is the fact that while the fylgja most often appears as an animal, sometimes there are scenes in the sagas where a figure in the form of a woman (usually in a dream or vision or some other exceptional, non-normal context) is called fylgja, which resembles what we would expect to be called hamingja. Most scholars have treated animal-fylgjur and woman-fylgjur completely separately.

I'm at least partially inclined to agree with that approach. I think the word fylgja (which just means 'follow') gets thrown around a little much, and that not everything referred to with that word was ever meant to be seen as the same thing. In modern Icelandic the word fylgja can even refer to just a regular ghost that haunts a person (rather than a place, so it follows them from place to place; and an ættarfylgja haunts successive generations of a single family). When fylgjur appear in sagas in the form of human women, they sort of bleed into other categories like hamingjur or dísir and on the extreme end maybe even things the word valkyrja might apply to. If the word fylgja can be applied to any figure that follows a person, then a hamingja is a type of fylgja, just one that is different from the animal-fylgja.

To demonstrate, here are two very similar scenes from two different sagas:

In Hallfreðar saga, Hallfreðr suddenly gets deathly ill. His fylgjukona 'fylgja-woman' appears to him, big and wearing armor, able to walk on the sea as if on land (characteristic of valkyries in Völsunga-related mythology), and Hallfreðr declares that he is formally severing ties with her. Then the woman asks Hallfreðr's son Þorvaldr whether he would like to accept her. He says no, so she asks Hallfreðr's other son, who consents, and she becomes his fylgjukona.

In Víga-Glúms saga, Glúmr dreams of a huge woman, so big that her shoulders take up the entire breadth of valleys, touching mountains on either side. In the dream, he went outside to greet her and bid her welcome into his home. When he woke up, he interpreted this as meaning that his maternal grandfather had died and that his hamingja had come to Glúmr.

I don't personally find it clear whether these are supposed to be the same "type" of being or not. I think the easiest way for someone to try to simplify this would be to say that the author of Hallfreðar saga simply chose confusing wording, and could have said hamingja, or that fylgjukona is not the same as an animal-fylgja. I'm not gonna make that call, as I have no problem with the idea that the evidence really just is confusing and contradictory and I prefer not to give into the impulse to systematize.

Most often, when a figure is described as a fylgja, it's a sort of animal double. They're often deployed in the story to foreshadow death -- an animal representing a main character will be seen in a dream being attacked by other animals representing their enemies. A recurring motif is that people will be suddenly overcome with fatigue in the middle of the day and be unable to help falling asleep, in order to have these extraordinary dreams. People with special abilities, or people in highly unusual situations, may be able to see them without being asleep (I think this only happens once in the literature we have). In rare instances, these visions serve as warnings that enable the relevant people to actually avoid the fate they were headed toward (making it very different from other kinds of knowing the future in Norse literature, which in almost every other case is unavoidable).

The animal fylgja (or other things like it) has a place in later Scandinavian folklore but with all of the change, development, and speculation around it it's not possible to systematize or summarize it; this is a whole continuum of belief and not a single cohesive thing I can summarize. If you're interested in that a good start in English would be Scandinavian Folk Belief and Legend, edited by Reimund Kvideland and Henning K. Sehmsdorf. It's also very easy to conflate the fylgja with other kinds of animal affinity, like Kveldúlfr becoming a wolf at night or seiðmenn projecting their awareness outside of their bodies in the form of animals, but most scholars have considered this separate and I agree with them.

Despite the fact that hamingja is a little less all over the place, I find it even harder to describe. Usually the word just means 'luck' or 'happiness' in a general sense and doesn't refer to a discrete being or personality, yet the etymology suggests that, at least when the word started being used, it was applied to a specific sort of non-physical being. The word is believed to come from ham-gengja, something which "goes" (ganga) and is of hamr (roughly 'shape' or 'form' but a complicated discussion on its own).

Presumably this has made you have more questions than you started with but hopefully I have at least moved the locus of confusion somewhat.

For some further reading (for convenience, including the ones I already mentioned):

Kvideland, Reimund and Henning K. Sehmsdorf, eds. Scandinavian Folk Belief and Legend

Murphy, Luke John "Herjans dísir: Valkyrjur, Supernatural Feminities, and Elite Warrior Culture in the Late Pre-Christian Iron Age"

Sommer, Bettina Sejbjerg. "The Norse Concept of Luck"

Stankovitsova, Zuzana, "'Eru þetta mannafylgjur?' A Re-Examination of fylgjur in Old Norse Literature" (see also her bibliography)

79 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Brewing Viking Stone Beer (Susan Verberg)

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

For those of you who remember the Vindelev Hoard found a few years ago, they just announced this morning that one of the bracteates appears to be the oldest written source mentioning Óðinn by name.

The full article is forthcoming, but for now Krister Vasshus has posted a good informational thread with some links, and he will be posting further info on his Twitter account (such as the article) in the near future. For now, however, the thread is linked above, and the text with links (in Danish and English) can be found under the read more for those of you who'd prefer to avoid the birdsite.

iʀ Wōd[i]nas weraʀ

He (is) Óðin’s man

The runic inscriptions on one of the Vindelev bracteates from the 5th century has been a wonderful discovery. One of them will get some attention today.

Not only is it a long inscription (34 runes) where most of the words aren’t attested in other runic inscriptions in the Proto-Norse language, but it is also the oldest written source mentioning Óðinn by name. Runologist @lisbethimer and I have been working with the interpretation of the runic inscriptions on all the bracteates from Vindelev, and our academic article will be published soon. The inscription on the bracteate labeled IK 738 has 34 runes, and some of these are bind runes, meaning there are two letters in one rune.

This bracteate is so worn that some of the runes are difficult to see. There are no separation marks between the eight words in the inscription, and the last three words are iʀ Wōd[i]nas weraʀ, meaning ‘he (is) Óðin’s man’. Who is this man?

In our article we will present all the possibilities, but one of them is that the inscription already mentions him by the (nick)name Jaga or Jagaʀ.

To be clear: just because this is the first written record of Óðinn by name does not mean that people first started worshiping him in the 5th century. We have several indications that he has existed as a conceptual deity for much longer, although his traits and characteristics may have developed with time, and there may have been regional differences in how people have perceived him. I will post links to interviews etc. on this account where you may get more details, but for all details you will have to wait for the academic article.

Set your IP address to Danish and binge the show Gåden om Odin:

More news in Danish, and already the journalist had misinterprated our messages :D

More in Danish

Some info in English

124 notes

·

View notes

Note

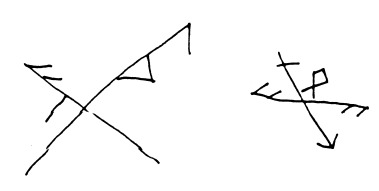

Do you know of any resources that list historical instances of bind runes? As in, like the triple (or sometimes more) stacked (tiwaz? tyr?) rune that looks like a tree, among others? When I try to search this online, I come up with almost exclusively modern creations, but I’m wondering how often this happened in the general past and what it looked like? Maybe bind rune isn’t even the correct historical term—I don’t know. Any insight you could provide would be great, thank you!

I expect that Bind-runes: An Investigation of Ligatures in Runic Epigraphy by Mindy Macleod would probably be exactly what you're looking for, but I haven't read it myself, so I can't guarantee.

The second-best idea that occurs to me is to just go through Texts and Contexts of the Oldest Rune Inscriptions by Tineke Looijenga with a ctrl+f find "bindrune." This only covers Elder Futhark.

The vast majority of bindrunes prior to the early modern period that we have a record for are simple ligatures of two, sometimes three runes, like ᛮ a͡l, and in most works about runes those aren't really treated differently from the much rarer, more complicated ones, which makes it harder to use search tools to find them. Complex bindrunes that are more than just simple ligatures are exceptionally rare in the Elder Futhark.

These are a type that Looijenga calls "cross-runes," which might be the only repeated "type" of bindrune in the Elder Futhark other than simple ligatures:

Really complex ones are far more prevalent in Icelandic manuscripts from the early modern era. In Runologia, his short book/long essay about runes, Grunnavíkur-Jón (1705-1779) has a few sections on composing bindrunes. Runologia is a weird combination of an academic work in the tradition of Ole Worm, Icelandic vernacular practice, and vernacular reappropriation of academic work; all of this makes it very interesting but difficult to use for tracing the historical precedent of anything in it. It's hard to say whether he was recording a widespread practice or systematizing something he had a vague idea of.

I have a post with a couple of examples here: https://thorraborinn.tumblr.com/post/682508486233440256/how-do-you-make-bind-runes-without-using-elder

46 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Stefan Koidl (Austrian, b. Austria, based Hallein, Austria) - Hello There, Paintings: Digital Art

198 notes

·

View notes

Text

Seal fur thong. 19th century. Inuit in East Greenland

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Whenever I need a good laugh I go to Loki, but whenever I have questions about philosophy, I go to Brigid's husband, Eochu Bres.

A while back I asked him something around the lines of, "How would you define 'discipline' outside of the ableist connotations it usually has?"

And his reply was something like, "Discipline would be your willingness to learn something accurately, and in accordance to best practices, if applicable. In other words, to invite course-correction and to avoid cutting corners."

(Not sure if this applies to all scenarios, but I was thinking of discipline in terms of learning a skill, so that's the context I received the answer in.)

Anyway, I think about this sometimes.

681 notes

·

View notes

Text

Masterpost: Frīg's Handmaidens Project

Who are the Handmaidens?

In the Prose Edda, twelve Goddesses are listed after Frigga as Ásynjur: Fulla, Gefjon, Hlín, Syn, Eir, Sága, Gná, Vár or Vór, Snotra, Vör, Lofn and Sjöfn. Modern Heathens sometimes refer to Them as Frigga's Handmaidens. (This is a piece of shared gnosis, not an historically attested term.) For many of the Twelve, this is all that survives in the way of attestations.

What is the Project?

Gradually over several years, and more intentionally recently, I have been building a devotional cultus around these Goddesses. As part of that, I've been putting together primers on each of the Twelve on my longform blog -- detailing Their surviving attestations, Old English God-names and epithets for Them, my own personal experiences and upg, a prayer, and devotional icon art -- as well as essays and modern myths exploring other aspects of Them and my cultus to Them.

Although I use Old English names for Them and honour Them in a syncretic heathen practice drawing on influences from across the British and Irish Isles, I hope these may be useful and/or interesting for practitioners working in a Norse, Continental, or other context. Or for anyone worshipping and building cultus to lesser-known and lesser-attested Gods!

I will update this post periodically, but if you like you can subscribe to my longform Wordpress blog for updates when I post.

Primers

Fulla

Geofen (Gefjon)

Hlēowen (Hlin)

Ār (Eir)

Saga

Essays and other posts

Introduction to the Project

Essay on abundance, ānanda, and Fulla

Essay on Frīg and Her importance to my cosmology

The Wren and her sister: a myth of Frīg feat. Ār and Gnæ

Essay on marriage as initiation, feat. Lofen, Siofen and Āþ

119 notes

·

View notes