Text

Fëanor and the Silmarils: like creator, like creation?

"The heart of Fëanor was fast bound to these things that he himself had made."

Art can take many shapes and forms, hold many different meanings, and tell many different stories. It can be appreciated for what it is on its own, or what it means within the context of how it came to be.

But despite the many different approaches to art, one thing is certainly true in general: there will always be at least a small connection between a piece of art and its creator, because without the creator it would not exist. This fundamental importance at least is the imprint of any creator on their creation.

Fëanor and his Silmarils are no exception.

”Silmarils of Feanor” by Nikulina-Helena on DeviantArt

With the Silmarils Fëanor undoubtetly left a markt on the world, and it's fascinating to explore some of the similarities between Arda's most famous elf and most famous jewels, but also the aspects where they are fundamentally different.

Uniqueness

Fëanor was a very exceptional elf. He was made “the mightiest in all parts of body and mind, in valour, in endurance, in beauty, in understanding, in skill, in strength and in subtlety alike”¹ and no other elf has ever been described in a way that could be compared to this. In a similar way there were no other gems created that were like the three Silmarils: they are exceptional as well.

Fëanor did not create the Silmarils in a vortex of course: without the Two Trees it's basically impossible to recreate such jewels. But even while the Trees were ailve it was very unlikely that jewels as these could be recreated. Even Fëanor said that “never again shall [he] make their like”¹. With Fëanor being gone as well, it's basically impossible.

Attraction

People have intense feelings for both Fëanor and the Silmarils. There is hardly someone that does not feel some kind of interest, attraction or love for them – or intens hate. They are basically impossible to ignore.

Fëanor has the love and loyalty of many people – first and foremost his father, but also his seven sons, and a large part of the Noldor. He was said to be "a master of words, and his tongue had great power over hearts when he would use it"¹. As a result he had a large following amon the Noldor.

Even Melkor has an eye on him and picks him as his main focus for the corruption he’s spreading among the Noldor. And he’s not the only Vala who pays attention to Fëanor, the others “mourned not more for the death of the Trees than for the marring of Fëanor: of the works of Melkor one of the most evil”¹ – and that is quite a statement. Even ages later, Fëanor comes up when Gandalf talks to Pippin about what or who he would like to see if he would use the Palantíri:

“Even now my heart desires to test my will upon it, to see if I could not wrench it from him and turn it where I would-to look across the wide seas of water and of time to Tirion the Fair, and perceive the unimaginable hand and mind of Fëanor at their work, while both the White Tree and the Golden were in flower!”²

The Silmarils are even worse when it comes to their power of attraction, everyone wants them: Fëanor himself of course, but the Elves and Valar want to see the Silmarils at festivals as well. Melkor obviously wants them, and once they’re stolen the sons of Fëanor want them back. Thingol wants them, Lúthien and Beren want them, Dior wears it, Elwing too, and eventually Eärendil. Almost noone is ready to give them up.

Disaster

What the Silmarils and Fëanor also have in common is for almost all people that come in contact with them to somehow end up involved in one disaster or another.

Fëanor already has an unfortunate start when his birth demands so much energy from his mother that she eventually dies. His father Finwë dies as well, protecting Fëanor’s Silmaril in their house in exil – an exil that Finwë had taken upon himself for the sake of being with his son. All of Fëanor's sons join him in taking the Oath, and end up suffering as a result. The Noldor that follow Fëanor’s rebellion suffer as well, and so do the Teleri that stand in his way. And while Nerdanel herself may remain unharmed, she loses all her son's to Fëanor's quest.

The Silmarils have that effect to some extent as well: once Melkor sets his sight on it, they are a major reason why he specifically targets Fëanor, they are also the reason why Finwë is killed when he tries to defend them against Melkor, and they burn Melkor when he steals them. In a way they become a curse for Fëanor’s sons who cannot rest until they get them back, they are the excuse for Thingol to send Beren to Angband which eventually leads to Beren’s and Lúthien’s death (they get better), it leads to Thingol’s death, to Dior’s, the fall of Doriath and to Elwing’s death. Their main redeeming quality is then that they help Eärendil get to Aman.

The distruction they cause is closely connected to Fëanor: the oath that he and his sons swore seem to be not unlike a curse on the Silmarils. And maybe it is only this powerful of a curse because in origin they are Fëanor's creation. Why else should they bring so much pain and suffering to whoever keeps them? Then Melkor’s desire, Dragon gold and a dwarve’s curse make it even worse.

Impact

Fëanor and the Silmarils both leave the world in a way. Fëanor is dead, and although one of the Silmarils can still be seen in the night sky, it can no longer be reached by the inhabitants of Middle-earth.

Fëanor and his creation, despite being now largely absent in Middle-earth itself, had a huge impact on Middle-earth. For Fëanor it can be said that without him, the Noldor probably wouldn't have returned to Middle-earth. He was the central figure in this movement. Without him, the history of Middle-earth would be drastically different, and we can only speculate what would have happened. The dominion of Melkor in Middle-earth? The early destruction of Beleriand through the interventing army of the Valar? It's hard to say.

The Simarils also left their marks of course. Many people in Middle-earth had been motivated to do something because of the Silmarils – includign Fëanor himself, his sons, Melkor, Thingol, Beren, and so on. Especially relevant is the impact of the Silmaril that Eärendil gets his hands on – without the Silmaril, he would never have reached Aman. Even in later ages, the light of the Silmarils continues to play a role: without its light, Frodo and Sam would never have been able to face Shelob head on.

The Silmaril's impact is Fëanor's impact as well, since he is their maker. In addition, he also has created many other things that lasted through the ages and had an impact on history – the best example after the Silmarils being the Palantirí.

Differences

I'm sure there are many differences to be found between Fëanor and his Silmarils, but I only want to point out what to me is the most important one:

Despite everything that was laid on the Silmarils, they were never corrupted. Their light was never dimmed, they never turned evil – they were made out of some unkown and unbreakable material, and hallowed by Varda herself, protecting them against all evil.

Fëanor wasn’t like that. There was no protection against Melkor’s subtle corruption after the Valar had set melkor free in Valinor, and Fëanor by his firey nature may have been especially receptive for it. Murder, lies, rebellion – “evil” on that scale hadn’t been seen before in Valinor.

The Silmarils couldn’t be corrupted, but Fëanor could fall.

(On a less serious note: my family’s questionable contribution to this topic was that if you take Fëanor’s ashes and press them into a diamond he becomes more similar to a Silmaril.)

FOOTNOTES

¹ J. R. R. Tolkien, edited by Christopher Tolkien. The Silmarillion.

² J. R. R. Tolkien. The Lord of the Rings, The Two Towers.

#Tolkien#Middle-earth#middle earth#Silmarillion#LOTR#Silmarils#Feanor#The Silmarillion#my posts#essay#silm#quenta#noldor

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Legolas, who is young by elf standards, A wood elf, who worships the stars and light. stuck underneath a mountain, in the dark. He's used to the dark, the suffocating darkness that has taken hold of his home. but here underneath stone he's cut off from nature, he can't hear it, feel it. its alien. Legolas, who's grown up with stories of ages past, fiery creatures made to destroy elves. These things killed the greatest elves of the first age. Things of nightmares. Legolas who knows something is wrong, can feel the darkness take hold of his fëa and the thing from his nightmares, the horror stories is right there. And he's an elf, away from familiar grounds and starlight and there is a Balrog. He's and elf and thats a balrog.

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Idea for the poll submitted by anonymous – slightly altered.

#reblogging for the passion for language and writing#reminds me of the video of Tolkien writing in tengwar and then goes “oh I made a mistake there didn't I?”#idk what it was but it would be very funny if that was such a mistake#anyway#Quenya#Tengwar#poll#Shibboleth of Feanor#Shibboleth of Fëanor

179 notes

·

View notes

Text

Even as he threatened, so it fared.

From time to time in the eyeless dark

two eyes would grow, and they would hark

to frightful cries, and then a sound

of rending, a slavering on the ground,

and blood flowing they would smell.

But none would yield, and none would tell.

– “The Lay of Leithian” by J. R. R. Tolkien

#Tolkien#quotes#middle-earth#Silmarilion#The Silmarilion#my posts#the last line y'all#it sounds so eerie and sad#and it's so poetic at the same time#it's a perfect line#and lives in my head rentfree

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

‘The wide world is all about you: you can fence yourselves in, but you cannot for ever fence it out.’

– "The Lord of the Rings" by J. R. R. Tolkien

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

‘But where shall I find courage?’ asked Frodo. ‘That is what I chiefly need.’

– "The Lord of the Rings" by J. R. R. Tolkien

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Topics & Themes in Tolkien’s Legendarium

The Perilous Realm

“Stories that are actually concerned primarily with ‘fairies,’ that is with creatures that might also in modern English be called ‘elves,’ are relatively rare, and as a rule not very interesting. Most good ‘fairy-stories’ are about the adventures of men in the Perilous Realm or upon its shadowy marches.”

– J. R. R. Tolkien. On Fairy Stories.

Tolkien called it the Perilous Realm, Faery or Faërie, and for me these words represent one of the most fascinating theme in Tolkien’s Legendarium. It is both a narrative and a world-building element that can be found in all his major Middle-earth stories and is in a way essential for understanding Tolkien’s approach to his own created world.

Yet I feel it rarely gets talked about, so I want to briefly highlight what it is, how it functions in the narrative, and give a few examples from various stories. Unfortunately can’t go into a deep analysis because doing so would require me to write a book – which I would love to, but I don’t have the time or qualification). Quote sources and further reading recommendations are given at the end.

WANDERING INTO FAERY

“It is common in Fairy tales for the entrance to the fairy world to be presented as a journey underground, into a hill or mountain or the like. [...] My symbol is not the underground, whether necrological and Orphic or pseudo-scientific in jargon, but the Forest […].”

– J. R. R. Tolkien. “Smith of Wooton Major” essay.

The core of this theme is the mortal wanderer who comes to or crosses the borders of Faërie, the land of fairies or elves. This idea has been part of legends and myths for a long time, one of the most prominent examples probably being the island of Avalon in the Arthurian legend. Depending on the story, Faërie can occupy a different time and space than our own world, or share the same space or time “in different modes”. Getting into Faërie is not always possible and many things can stop someone from entering: it may be completely inaccessible, it may be hidden and people have to find it, or it may be accessible only to those who know the secret on how to enter it. Once you are there, it may be difficult to leave, or it may take some time. Being there could turn out to be dangerous, but it also doesn’t necessarily have to be. Tolkien wrote that “in it are pitfalls for the unwary and dungeons for the overbold”.

In The Lord of the Rings, there are many examples of such a realm, some barely noticeable and some very clear and detailed.

It starts subtle when Frodo, Sam and Pippin meet Gildor and his Elves near Woodhall. It is no specific realm that they enter, but just wandering with the Elves already lets the Hobbits experience something they are not used to. They have trouble finding words for it afterwards or remembering it clearly, with Tolkien describing it that for Pippin it felt like he was in a waking dream. The next example is then already more direct: the four Hobbits enter the Old Forest. This time it really is perilous for them, they get lost and cannot find a way out. Tolkien describes it as follows:

“They began to feel that all this country was unreal, and that they were stumbling through an ominous dream that led to no awakening.”

Frodo almost falls asleep near an enchanting river, Merry and Pippin almost die. Without the help of an unexpected inhabitant of this forest, they never would have gotten out.

Reaching Rivendell is another less clear example. Rivendell itself is easier accessible than the Old Forest and less perilous for the Hobbits. But reaching it also includes a river, a river that is under Elrond’s command and that rises “in anger when [Elrond] has great need to bar the Ford”. And within Rivendell, Frodo experiences another kind of “Faërian Drama” as Tolkien calls it: the stories and songs told in Rivendell hold him “in a spell”, and “the enchantment became more and more dreamlike” until in the end Frodo falls asleep once more. Bilbo comments that it’s difficult to stay awake “until you get used to it”.

The most prominent example is of course Lothlórien, a land of Elves that is rarely visited by mortal beings and where the flow of time is indeed different than that in the outside world. It’s also well defended against wanderers, and both in the world and the narrative the fellowship has to pass through: there are guards at the boarders that have to be convinced, there is a river that has to be crossed, a hidden path that has to be taken blindfolded. Tolkien is in no rush to get the fellowship to Galadriel – the reader, together with the wanderers, have to experience this journey.

The purest form of this theme in The Lord of the Rings is, of course, Frodo and Bilbo leaving for the island Tol Eressëa at the end of the story. It is the longest journey into Faërie, a journey that only a few are allowed to take and that you won’t come back from. Tol Eressëa is no longer in the space of the human world, and it’s very telling that Tolkien named the haven on the eastern shore on the island Avallónë.

More examples can be found in Tolkien’s other stories, and I will mention them less detailed when talking about the actual centre of the theme:

THE MORTAL VISITOR

„It seemed to [Frodo] that he had stepped through a high window that looked on a vanished world. A light was upon it for which his language had no name. All that he saw was shapely, but the shapes seemed at once clear cut, as if they had been first conceived and drawn at the uncovering of his eyes, and ancient as if they had endured forever.”

– J. R. R. Tolkien. The Lord of the Rings.

All of Tolkien’s major stories have one thing in common: they have someone human at the core who is unfamiliar with Faërie and able to experience it as new and from an outside perspective.

In The Hobbit it is Bilbo who stumbles into a world he is not prepared for at all, and while it is less clearly shown in the narrative of a children’s book, the journey of Bilbo and the Dwarves clearly show signs of this theme – a dangerous forest, an enchanted river, a white deer, and Elven fires that suddenly vanish.

For The Lord of the Rings I have shown above that all four Hobbits experience this in one way or another, although Frodo is probably the one given the most focus.

“This is a history in brief drawn from many older tales; for all the matters that it contains were of old, and still are among the Eldar of the West, recounted more fully in other histories and songs. But many of these were not recalled by Eriol, or men have again lost them since his day. This Account was composed first by Pengolod of Gondolin, and Aelfwine turned it into our speech as it was in his time, adding nothing, he said, save explanations of some few names.”

– J. R. R. Tolkien. Quenta Silmarillion.

The Quenta Silmarillion is a different type of story, so here the theme also takes a different form: it’s not a narrative as The Hobbit or The Lord of the Rings and more a historical chronicle in style. It’s written as such, but also given the corresponding context: when Tolkien was first writing the Book of Lost Tales and later the Quenta Silmarillion, the framework he had built for it was that of a mortal men coming to Tol Eressëa and learning of these past events. The one wandering into the Perilous Realm is Eriol or Ælfwine, listening to the stories of the Elves and writing them down for other humans to read. When Tolkien eventually started writing The Lord of the Rings, he was able to change his framing story. There was no longer a need for Ælfwine to reach Tol Eressëa to learn about these tales – now it’s Bilbo who wrote it down in three volumes called “Translations from the Elvish” that he had added to his private diary when he handed it over to Frodo.

This concept applies to the Quenta Silmarillion as a whole, but the main three stories within the Quenta Silmarillion still have a similar mortal visitor as The Hobbit or The Lord of the Rings. In Beren and Lúthien, it’s the mortal Beren who wanders into the Elven Kingdom Doriath and gets enchanted when he sees Lúthien dancing and singing. In the Children of Húrin, it’s Túrin who enters Doriath as well, but also the Elven Kingdom Nargothrond. Both times, Túrin is unable to find the entrance himself; he is lead there by Elven guides – first Beleg, then Gwindor. And in the Fall of Gondolin, Tuor is led by an Elven guide to through many gates under a mountain to the Elven Kingdom Gondolin – one of the rarer cases of a "journey underground, into a hill or mountain".

And even the Akallabêth incorporates this theme, although in a different way than the previous stories. The story of the Fall of Númenor is about wanting to go to Faërie, and not being allowed to. There are other aspects to this as well of course, but looking at it with this theme in mind, that is the core of the story. Ar-Pharazôn is the mortal man who desires to reach Faërie, but when he tries to get there by force it ends in his death.

The mortal visitor as the protagonist in their story is essential for this theme to work. To experience Faërie as a visitor, to enter a “dream that some other mind is weaving” in such a way, it is a uniquely mortal experience that the reader could imagine to have, but that the immortal Elves can almost never share – after all they create their realms, they are the creator of a dream that the mortal wanderer, Tolkien as the writer, and we as the reader are dreaming.

THE CREATOR OF THE DREAM

“Faërie contains many things besides elves and fays, and besides dwarfs, witches, trolls, giants, or dragons: it holds the seas, the sun, the moon, the sky; and the earth, and all things that are in it: tree and bird, water and stone, wine and bread, and ourselves, mortal men, when we are enchanted.”

– J. R. R. Tolkien. On Fairy Stories.

The immortal creators are not irrelevant of course, although they cannot be the centre of any story about wandering into the Perilous Realm. The outsider experience, essential for this theme, cannot come from the one living inside the Perilous Realm. The inhabitants in Tolkien’s stories are Elves most of the time – near Woodhall, in Rivendell, Lóthlorien, Mirkwood, Gondolin, Doriath and Nargothrond. But they are of course not the only creators of such realms. Dwarves come in and out of these stories, and in the case of the Old Forest the implication is that Old Man Willow is the main force behind the spell:

“His grey thirsty spirit drew power out of the earth and spread like fine root-threads in the ground, and invisible twig-fingers in the air, till it had under its dominion nearly all the trees of the Forest from the Hedge to the Downs.”

And of course the Valar and Maiar have their part in the story. Especially Tol Eressëa and Valinor are mainly built by the Valar, and in Middle-eath the magical boundaries of Doriath were set by Melian. In moments where Fëarie is not solely or not at all made by the Elves, they may enter the dream of another mind as well. It happened when the Elves first came to Valinor, and a more personal example is Thingol meeting Melian for the first time, where “an enchantment fell on him” in which he was caught for years without moving. This is only possible, however, when Elves meet someone with a creative power far greater than them – one of the Maia or above is required.

However, this was never Tolkien’s focus. In Tolkien’s stories, the Perilous Realm is often a place inhabited by the Fair Folk – but I have also mentioned that sometimes Faërie exists in another mode. Throughout the examples given, dreams have been an important element of the experience of Faërie, and it’s one that Tolkien also thought a lot about. In our own world, we cannot reach Faërie in our space, but it may be approachable in another mode – through dreams. This becomes especially apparent in his texts The Lost Road and The Notion Club Papers, and it was also a part of how Tolkien saw his own relationship with his work: a mortal entering a dream of Faërie.

ENDING THOUGHTS

There are many aspects of this that I haven’t touched on, and that I would love to explore or discuss. There is for example the case of Frodo, a mortal who has been in touch with something that belongs into the world of Faërie, that he cannot properly come back: when coming back to the Shire, Marry comments on how it feels like a dream is slowly fading, like he is waking up. Frodo however says: “To me it feels more like falling asleep again.” Already, it is clear he can never fully return.

Then there is the case of reversing the idea of Faërie in the case of Túrin – he is trying to bring Nargothrond closer to the outside world so that he can use its force in war. In return, he makes it accessible and the kingdom falls. In general, it’s a fascinating thing to see Túrin’s relationships with the Perilous Realms.

Or if we talk about dreams, what about the nightmares? Is Mordor basically an anti-Faërie, inhabited by Orcs instead of Elves, where the path leads through a spider lair instead of over a river, and where any mortal being can only end up as a corrupted slave if they stay there for too long?

What about including such an essential theme in adaptations? In Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings movies, flawed as they may be at times, the experience of Faërie through the eyes of the Hobbits is notable – especially in Rivendell and Lóthlorien. Meanwhile in Amazon’s The Rings of Power, this theme is completely absent and the Elven realms in Middle-earth have no more mystery than a Harfoot camp or a random human village in the South.

I hope I get to explore this theme more, I’ve been eager for month to write at least a tiny bit about it and it’s already way too long for tumblr again. But there are other themes that are also very interesting, so we’ll see how it’ll go…

If you have read up to here to the end I would like to thank you for your time and attention – both is much appreciated!

READ MORE ON THIS TOPIC

On Fairy Stories, an essay by J. R. R. Tolkien.

Smith of Wootton Major, by J. R. R. Tolkien.

The Lost Road, fragments by J. R. R. Tolkien.

The Notion Club Papers, fragments by J. R. R. Tolkien.

Faërie: Tolkien’s Perilous Land, an essay by Verlyn Flieger.

A Question of Time, by Verlyn Flieger.

QUOTE SOURCES

J. R. R. Tolkien. On Fairy Stories.

J. R. R. Tolkien. The Lord of the Rings.

J. R. R. Tolkien, edited by Christopher Tolkien. The Silmarillion.

J. R. R. Tolkien; edited by Veflyn Flieger. Smith of Wootton Major ‘Extended Edition’, Smith of Wootton Major essay.

J. R. R. Tolkien, edited by Christopher Tolkien. The Lost Road and other Writings, Quenta Silmarillion.

#Tolkien#Middle-earth#middle earth#The Lord of the Rings#LOTR#The Silmarillion#Tolkien themes#the Perilous Realm#Feary#my posts#essay

17 notes

·

View notes

Note

I am so sorry I misread your poll and rambled about Morwen and Niënor in the comments of your poll on father child relationships.

Love seeing the polls you put out!

-@outofangband

It's all good, I have a soft spot for passionate fans. ♥ Thank you for the kind feedback!

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hi all – currently I don't have time to write or read much, so I'm not really posting. However, I felt like creating polls. Since this is not what I actually want to use this blog for, I've created a little sideblog to post polls whenever I feel like it.

So if you are interested in answering polls about Middle-earth and Tolkien every once in a while, go and follow @middleearth-polls.

#tolkien#middle-earth#the silmarillion#lotr#tumblr polls#I hope I can find more time to write about Tolkien again... ._.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

”Then said Littleheart son of Bronweg: 'Alas for Gondolin.' And no one in all the Room of Logs spake or moved for a great while.“

I want to know what Tolkien line hits you hard every time. Where you are just left stunned. It can be from the books, movies, a scrap of paper the Professor wrote on once, whatever. Share your impactful line!

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

"Revised and Expanded Edition - The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien" coming in November 9, 2023!

Description:

The comprehensive collection of letters spanning the adult life of one of the world’s greatest storytellers, now revised and expanded to include more than 150 previously unseen letters, with revealing new insights into The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings and The Silmarillion.

J.R.R. Tolkien, creator of the languages and history of Middle-earth as recorded in The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings and The Silmarillion, was one of the most prolific letter-writers of this century. Over the years he wrote a mass of letters – to his publishers, to members of his family, to friends, and to 'fans' of his books – which often reveal the inner workings of his mind, and which record the history of composition of his works and his reaction to subsequent events.

A selection from Tolkien's correspondence, collected and edited by Tolkien's official biographer, Humphrey Carpenter, and assisted by Christopher Tolkien, was published in 1981. It presented, in Tolkien's own words, a highly detailed portrait of the man in his many aspects: storyteller, scholar, Catholic, parent, friend, and observer of the world around him.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

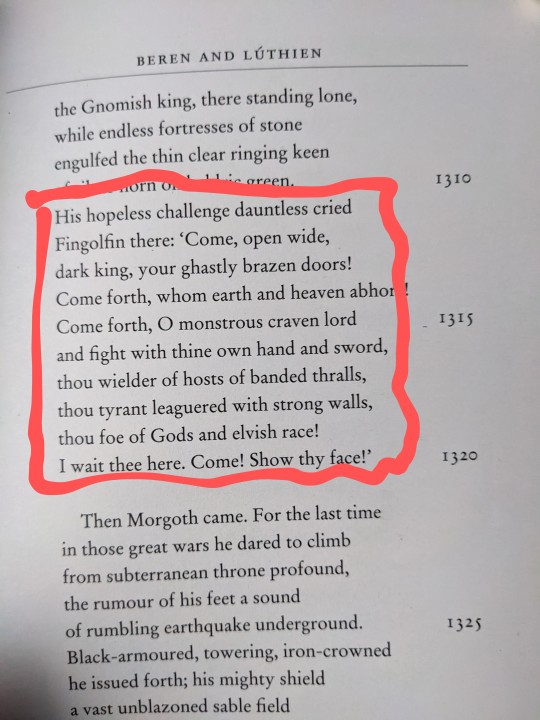

May I just add that in a fragment of the Grey Annals, Fingolfin also called him a lurking lord...

So we agree that 'jail-crow of Mandos' is an iconic Feanor quote, especially considering he said it to Melkor (of all beings!) while telling him to get off his lawn.

What we haven't spoken much about is this:

Feanor 🤝 Insulting Melkor 🤝 Fingolfin

Also now I want Finarfin to take a turn at yelling at Melkor. I think he deserves it too.

872 notes

·

View notes

Text

A fascinating discussion. I think it makes a lot of sense that there is no language spoken in Mandos when Elves have no bodies there. And this discussion shows why it's such an unnatural state dor Elves to be in – the experience of the world and all their relationships to others go through our physical body, the experiences they make are all influenced by the body. The fëa without the hröa is not whole.

So it makes sense that memory would also be different in Mandos, and that being revived one has to relearn language. I'm fascinated by the idea of Fëanor coming back eventually, and maybe learning to speak Quenya with s instead of þ (if that hasn't changed by then yet again), and those who used to know him are somewhat freaked out by this (but also happy that this is no longer a cause for conflict). I imagine that being the language nerd that he is, Fëanor would nonetheless read his old passive-aggressive writings about it and also relearn the old way of speaking, but no longer use it.

Finrod said "in memory is our great talent" and I can only imagine how important songs and poetry is for learning to reclothe memories in words.

I hadn't previously seen it in this context, but now "Finrod walks with his father beneath the trees in Eldamar" is a different scene altogether for me. We usually assume Finrod was re-embodied rather quickly, but he would have to relearn language nonetheless. Maybe that's happening in this very scene.

my friend, who listens to my constant speeches about the Silmarillion, just asked what language is spoken in Halls of Mandos, and I'm absolutely bewildered

418 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Authority of the Heren Istarion

I was watching the Tolkien Lore video about the wizard staves in The Lord of the Rings, and have some thoughts of my own about the staff of the wizards and the question of whether or not the wizards need them for their magic.

Since all the uses of Gandalf using the staff have been already listed in the linked video, I'll simply start with my thesis:

The staves of the Istari is a symbol of authority,

and through this connected to the use of magic.

The Istari: Stewards of Middle-earth

Staves can be walking sticks without meaning, but they can also be loaded with symbolism. You'll find it coming up throught history both in mythologies and in real life. Think of all the truly magical staves in fantasy settings. Think of the white staff as the emblem of some officials in the Royal Households – among them the Lord High Steward – of the United Kingdom.

Even in Middle-earth, Denethor as the steward of Gondor carries a white rod as a token of his office. So connecting the staves of the wizards with the authority of the Valar in Arda is not too far fetch I believe. Think of how Gandalf told Denethor:

“For I also am a steward. Did you not know?”

And in the essay The Istari, it is said about them that they were “Emissaries [...] from the Lords of the West, the Valar, who still took counsel for the governance of Middle-earth”.

Authority: an amplifier of might

In the essey Ósanwe-kenta Tolkien gives us a great insight into parts of the inner workings of his world. It does not talk about magic per se, but explains how the communication of thought works. But I believe we can take some hints from there and apply it to the use of other forms of what would look like magic to us.

For that we have to keep in mind that the Istari were “clad in bodies as of Men, real and not feigned, but subject to the fears and pains and weariness of earth, able to hunger and thirst and be slain”.

This means that their bodies themselves weren't necessarily very special of magical, but nonetheless the spirit inside these bodies were immortal, and also powerful – but limited by their current form. For the communication of though, passing thoughts through mortal bodies was difficult, but doing that could become more effective by strengthening it – and one way to strengthen it is by authority:

“Authority may also lendforce to the thought of one who has a duty towards another, or of any ruler who has a right to issuecommands or to seek the truth for the good of others.”

Given the fact that authority is very important in Tolkien's world, I believe it's fitting to apply this to the use of magic as well. It becomes especially interesting if we consider that Gandalf usually uses the staff when he interacts with the world around him, and rarely ever when it's about himself. If we see the staff as a sign of authority of the Valar, or even Eru himself, it could be a way of the Istari legitimating their use of power in Middle-earth with this.

Saruman the White: the chief of the Order

With the focus of the staves on authority, this may even explain why Saruman probably didn't take Gandalf's staff when he imprisoned him on Orthanc. If the magic of the Istari comes mainly from authority, then Gandalf the Grey with or without staff would have a lower authority than Saruman the White, who initially was the chief of the Heren Istarion, the Order of Wizards.

Gandalf did not put up much of a fight against Saruman because through their hierarchy Saruman was more powerful and didn't have to fear Gandalf. Anything that Gandalf was able or allowed to do, Saruman would be able to match in power and the take it further.

‘ ‘‘Until you reveal to me where the One may be found. I may find

means to persuade you. Or until it is found in your despite, and the Ruler has time to turn to lighter matters: to devise, say, a fitting reward for the hindrance and insolence of Gandalf the Grey.’’

‘‘That may not prove to be one of the lighter matters,’’ said I.

He laughed at me, for my words were empty, and he knew it.’

Why would Saruman be bothered about Gandalf keeping his staff if he probably was able to snap it a will at that time? He probably just didn't do it because he still hoped to convince Gandalf to join his side. In that scene quoted above both know that Gandalf doesn't really have the means to defend himself – Gandalf admits his reply to Saruman's threat were empty words, and that Saruman laughed because he was well aware of this.

This implies that both wizards were clear about their power and possibilities in this moment.

Gandalf the White: the chief of the Order

I belief that Saruman may have been able to do break the staff of Gandalf the Grey because Gandalf the White was able to do so with Saruman's staff. Sure, Gandalf the White is probably more powerful and less restricted than any of the other Istari before, having been resurected by Eru and all, but Gandalf the White still described himself as “Saruman as he should have been”.

At any rate Gandalf the White has a higher authority than Saruman of Many Colours. This is very directly demonstrated when Gandalf the White indeed breaks Saruman's staff and casts him from the order:

“[Gandalf's] voice grew in power and authority. ‘Behold, I am not Gandalf the Grey, whom you betrayed. I am Gandalf the White, who has returned from death. You have no colour now, and I cast you from the order and from the Council.’

He raised his hand, and spoke slowly in a clear cold voice.

‘Saruman, your staff is broken.’ There was a crack, and the staff split asunder in Saruman’s hand, and the head of it fell down at Gandalf ’s feet. ‘Go!’ said Gandalf. With a cry Saruman fell back and crawled away.”

Here Gandalf the White is powerful enough to destroy Saruman's staff, he has the authority to strip Saruman of his own authority.

— That's my two cents on the matter.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

In this post I wrote about how the great singers in Middle-earth can use their magic in songs, including memories and evoking images to strengthen their songs.

I'm excluding the Valar because they have unfair advantages, having sung the world into being and all...

13 notes

·

View notes

Note

Your Silmarillion metas are incredible and so well thought out!

-@outofangband

Thank you very much, that's very kind of you to say. 🙂 I rarely have time to write meta, so I'm happy to hear you noticed them anyway, and I appreciate it a lot that you took the time to send me this message message.

0 notes

Text

"Leithian"

Tol-in-Gaurhot

Finrod

mixed media, 63*44 cm

#Finrod#fanart#Elena Kukanova#this is a masterpiece#there aren't very many fanarts of this part of the lay#or at least I haven't seen that many...

2K notes

·

View notes