Text

The Siege of Chattanooga

In 1903 the newly incorporated Ford Motor Company manufactured and sold its first Model A; The Great Train Robbery, a short silent film, became America's first blockbuster movie; and the Wright brothers flew for the first time in what turned out to be twelve seconds that changed the world! That same auspicious year, the Winona Assembly anticipated its ninth season by designing an ambitious Chautauqua program that advertised the most elaborate Fourth of July celebration in the park's history.

Spring ignited a frenetic effort that lasted through the summer. The park transformed into a veritable little Venice with its man-made lagoons and islands. Work commenced on one hundred new cottages, not to mention the erection of a power plant to provide electricity and heat for year-round habitation. The basement of the big hotel became the site of a new spa where guests could bathe in the waters of Winona's famous mineral springs. The auditorium underwent renovations to double the seating capacity to four thousand. Workers also broke ground for the Winona Agricultural and Technical School, a three-story memorial to the late Governor James Mount.

New buildings went up and old ones came down, among them the gymnasium—a massive, circular structure that had been remodeled, repurposed and repaired multiple times since the Winona Assembly purchased Spring Fountain Park in1895. Finally, the Assembly designated the eyesore for demolition. But in the hearts of some locals, the removal of what they knew as “the old cyclorama building” struck a melancholy note, for they recalled with tremendous pride the Fourth of July fifteen years before when they had waited in line to behold a great spectacle called The Siege of Chattanooga.

* * *

The year was 1888. A steady stream of humanity flowed from the main road to the entrance of Spring Fountain Park for an unprecedented celebration of Independence Day. Elegant carriages, modest buggies, and rickety wagons conveyed excited visitors. Those who arrived by train poured in from the depot. On horseback and on foot, the residents from the nearby city of Warsaw joined the surge that coursed onto the convivial grounds of Indiana’s most popular summer resort.

A few hundred yards from the lake’s shoreline stood the brand new three-story luxury hotel wrapped in a spacious veranda and crowned with an observation room that overlooked the park and the lake. Those who dined there that day proclaimed the menu to be the very best in all the state. Crystal clear ponds, breathtaking flower gardens, rustic bridges, and a spring-fed fountain elicited cries of astonishment. The perfectly manicured lawns were as smooth as a billiard table.

The popular miniature steam train belched thick smoke as it chugged along the narrow tracks to the delight of both cramped passengers and charmed onlookers. Exhilarated shrieks erupted from the switchback, a car with six riders that coasted on wooden waves carried along by the forces of gravity back and forth between two towers. Delighted crowds lingered at the deer park, cheered for contestants competing in the boat races, laughed at the greased pig contest and stopped to watch a baseball game.

The extraordinary experience at Spring Fountain Park led one newspaper reporter to consecrate it as the perfect combination of God-given beauty and human ingenuity. Without a doubt, the lavish surroundings and sundry diversions inspired awe, but the nearly five thousand visitors converging on the park that day had come for one event in particular—their turn to enter the great cyclorama!

Ever since the first boards had been hammered into place two years before in 1886, the locals chattered non-stop about the extravagant new attraction and debated among themselves how much the daring enterprise must have cost the Beyer brothers, the park’s proprietors. They traded stories about America’s first panorama artist, Civil War veteran Harry Kellogg, and speculated about the role of the respected and influential General Reub Williams in bringing a battle panorama to the shores of Eagle Lake.

* * *

All day long a line stretched from the entrance of the cyclorama. Women in tall bonnets opened their parasols or ducked under trees for shade. Children dodged in and out of line playing tag. The men took up conversation with veterans who had been inside and who praised the flawless representation of the legendary military engagements.

Every twenty minutes a man appeared at the cyclorama’s entrance. He gave a shout. On cue, seventy-five excited patrons surrendered their tickets and filed inside the imposing building. Everyone’s eyes took a moment to adjust to the darkness before the group obediently followed its guide down a dimly-lit corridor to a winding staircase.

“Keep to the right!” The man called out repeatedly.

Seventy-five pairs of feet navigated a flight of steps in single file. Audible expressions of surprise reached the ears of those still climbing the stairs, causing hearts to race with anticipation. As the last spectators finally stepped onto the platform and beheld the breathtaking view, it was their turn to gasp and exclaim, for they found themselves standing on the slope of the legendary Missionary Ridge.

Amazed spectators crossed to the pine railing for a closer look. Below were shrubs, a fence, even a stream. They could not discern where the foreground ended and the painting began. They knew they had come to see a panorama painting, yet what met their eyes was so much more. They believed they were seeing soldiers, ammunition wagons, horses, guns and cannon. A host of optical illusions seduced their minds, and they could not un-believe the tricks employed by the clever artist. Three hundred feet of muslin reaching fifty feet high encircled them. A skylight funneled the sun’s rays onto the walls of the rotunda and illuminated the massive canvas.

Observers believed themselves to be in the midst of a Tennessee landscape that stretched for miles in every direction. Above them shone an azure sky strewn with thick, white cumulus clouds and feathery wisps of horsetails. Blazing yellow and red foliage sparkled against the lush greens in the valley where the winding Tennessee River shimmered and the Blue Ridge Mountains rose up in the distance.

This was the magic produced by three tons of paint on a two-ton muslin canvas, five hundred handcrafted papier maché figures and several tons of dirt that had been lugged in by wheelbarrows to form roads, creek banks and hills. The vegetation in the foreground was real, but the horses, wagons and men were not. In fact, none of the figures that beguiled spectators stood more than twelve inches tall.

* * *

“Welcome to Chattanooga, Tennessee!”

It was artist Harry Kellogg.

“The year is 1863 and the War of the Rebellion has reached a critical juncture. Which side will prevail? Relive with me a turning point of the war.”

All eyes were fixed upon the wiry, energetic host.

Kellogg took a step forward, opened his arms wide and announced, “Ladies and gentlemen, this is for me a very emotional moment because the battles I’ve depicted here are those I witnessed as a commissioned Union officer in the Army of the Cumberland.”

He paused dramatically before proclaiming, “This is your chance to hear from one who was there how it really happened!”

Commencing his narrative, Kellogg explained, “Early on the morning of November twenty-fourth, Union troops stormed Lookout Mountain, clawing their way up the sheer cliff. Rock by rock and tree by tree, they made their way in the face of heavy fire. Indeed, the Confederate position was considered unassailable, so what occurred that day was a miracle.”

He paused a moment before calling out, “Look there! Sitting on his white horse is General ‘Fighting Joe’ Hooker shouting at his troops to secure the summit. As his men rushed up the mountain, they and the enemy were engulfed in a cloud of gun powder and thick morning fog.”

“My friends, can’t you hear the deafening explosions that shook the earth as the two armies struggled behind the blinding cloud?”

Kellogg glanced around at his audience.

“It was impossible for those of us watching below to know which side was prevailing. Suddenly, our warriors caught a glimpse through the haze of battle—a flag waved in the distance. But whose flag was it? A loud voice resounded, ‘It’s Old Glory! It’s Old Glory! We did it!’”

“Lookout Mountain had been conquered!” Kellogg announced triumphantly.

“Ladies and gentlemen, do you think the siege has now been broken?”

“No, no, no!” They cried anxiously, shaking their fists. They knew that General Bragg still controlled Missionary Ridge.

“Look here! It is our brave hero General Sherman leading the attack on the ridge where you are right now standing. Alas, General Bragg had reinforced his troops against his advancing fiery, red-haired archenemy. Like an invasion of locusts, Confederate reinforcements quickly swarmed the northern ridge area. After eight hours of vicious fighting, Sherman’s army was undeniably pinned down.”

The spectators, gripped by Sherman’s plight, stared in silent horror at a battlefield strewn with trampled corpses. They thought they heard the screams of the wounded left unattended. Their hearts cringed at the sight of frightened horses wandering about in the decimated forest. Sabers, bayonets, and canteens littered the battlefield. Severed limbs and burning wagons told the harrowing disaster that Sherman’s men had faced.

“Ladies and gentlemen, do you think we could hope that Sherman would finally drive the Rebels from Missionary Ridge?"

They shook their heads.

“Oh, Look!” said Kellogg. “Do you see General Grant on a hill with his binoculars and wearing a look of dismay? And the other man? Who could that be? Why, that’s General Thomas, the Rock of Chicamauga! He, too, looks utterly astonished. What could explain their bewilderment?”

Kellogg pointed to a scene with a ragtag army of ferocious-looking men.

“These men are wretched, aren’t they? The Confederates defeated them at Chicamauga, surrounded them at Chattanooga and waited for them to starve. But what General Sherman could not do, the Army of the Cumberland did! Without orders, and to the shock of Grant and Thomas, these once-humiliated soldiers valiantly charged Missionary Ridge screaming, ‘Remember Chicamauga!’”

The rapt audience smiled at the Rebels retreating in stunned, wild-eyed disbelief, dropping their rifles, and fleeing with their arms raised as General Thomas’ men surged upward fueled by revenge. The enemy was deserting its positions, and in the midst of the Confederate chaos was General Bragg, his face contorted with despair while screaming at his troops to hold the line.

Then Kellogg pronounced with great delight, “Thus did the Army of the Cumberland successfully lift the siege of Chattanooga!”

The crowd erupted in a spontaneous cheer.

As the spectators slowly filed off of the platform to descend the staircase, they did so solemnly, shuffling through the darkened passage to the exit. At the same time that they stepped into the bright July sunshine, they left the Civil War behind. Shielding their eyes, they blinked pensively until they could once again bear the bright light of day. Turning to one another, spirits soaring with pride and wonder, all exclaimed, “It seemed so real!”

* * *

The Siege of Chattanooga ran until 1892 when the Beyer brothers replaced it with a new panorama called The Life of Christ begun by artist E. J. Pine in the spring of 1891. The summer of that year, Spring Fountain Park featured two partial panoramas: the first half of Pine’s biblical epic and a few existing battle scenes from Kellogg’s masterpiece.

Replacing panoramas was common practice. Unsurprisingly, audiences grew weary of one story and longed for fresh entertainment. This expensive demand soon collided with the rapidly advancing technologies of the approaching twentieth century. And just like that, movie theaters, not cyclorama buildings, burgeoned with audiences. The silver screen, not a gigantic canvas, cast its spell.

The cyclorama at Spring Fountain Park featured an extravagant grand opening for the Fourth of July in 1888 and closed permanently six years later. According to J. E. Beyer, Kellogg’s historic tribute to the Civil War became the property of the Winona Assembly when it purchased the park. The fate of that panorama and Pine’s Life of Christ remains unknown. The cyclorama was torn down in 1903, and its usable lumber distributed among various building projects that summer. ::

0 notes

Text

The Boy Problem

Boys City Drive is a short stretch of road in Winona Lake, Indiana. It terminates abruptly at the entrance to what was for decades known as Chicago Boy’s Club. This street name and an old sign with the word “Chicago” may appear as misnomers. In fact, they preserve a critical moment in both local and American history. Here is that story.

Judge Willis Brown, touted as the first judge of the first juvenile court in Salt Lake City, Utah, stood confidently before an audience of thirty men, all fairly advanced in age when compared to him. Yet the enthusiasm, knowledge, experience and wisdom of this clean-shaven twenty-four-year-old prodigy shattered any preconceived notions that youthfulness might otherwise have elicited. Besides, his reputation preceded him.

Before his judicial appointment in Utah, Willis Brown had served as a national leader in the war against cigarettes. He campaigned vigorously throughout the United States on behalf of the Anti-Cigarette League whose hard work had resulted in legislation outlawing “coffin nails” in Indiana. Cigarettes, league members argued, threatened to lead young people, especially boys, into other vices.

Judge Brown’s dedication to this national cause and his focus on recovering misguided youth led a Salt Lake City commission to install him as judge of its first juvenile court. Who was better fit for the task than Willis Brown?

That same question had the identical answer in the fall of 1906 at a meeting organized by Sol Dickey, Secretary of the Winona Assembly which was considering the establishment of a camp dedicated to the betterment of boys. At Dickey’s invitation, Judge Brown addressed the assembled benefactors.

“At the turn of the twentieth century, America faces a problem, one greater than the building of the Panama Canal or the sale of alcohol. One that is even more important than world peace! What is this crisis? Why, it’s the boy problem!”

The attentive men in expensive suits nodded as they glanced about in agreement with the speaker’s astute observation. All America fretted over what had come to be called the boy problem.

“The training which made a strong man a few years ago will not do for today. A boy is surrounded by temptations. He is lured by alcohol, indecent photographs, tobacco, and pool halls. Boys determine the destiny of this country because they are the foundation stones of our great republic.”

The judge paused before emphatically declaring, “We must fit the boy for useful citizenship!”

Brown’s vision enchanted his audience, for Boy City was to be a city run by boys. What genius!

The judge laid out with precision his plan for electing a mayor and a city council. Politically minded boys, he said, would run a campaign. Their peers would vote. Laws would be drawn up and enforced.

He described competitions among athletic teams, a band to entertain the Assembly’s summer guests, and a choir of at least three hundred voices.

“Every boy with a camera will bring his, and we will have a photography club with contests and awards.”

The captivating crusader proposed real commerce in the form of a functioning bank. He pledged a grocery store, restaurant, an ice cream shop and a daily newspaper. Boy City, the judge added, would be a tent city with eight wards. Each tent would have an address to which mail would be delivered by the city’s duly appointed postmaster.

“We will have utilities in the form of a telephone company and limited electricity.”

Judge Brown excited his listeners further by projecting a startling attendance of five thousand boys. The young denizens would have total charge of their city while the judge, his staff, and chaperones supervised them in drafting, implementing, and upholding its laws.

“A boy must be trusted or he will rebel,” the judge warned with all of the authority of a man who knows. “Winona Assembly need only provide the setting and the initial financing. All other responsibilities will fall to me.”

Brown’s magnetic delivery won over his enthusiastic audience. Sol Dickey and the Winona Assembly wasted little time in publicly announcing its partnership with Judge Willis Brown, promising a novel and effective approach to making boys into good citizens. Such a promise went a long way to comforting the many who despaired of the seeming inevitability of a boy’s corruption in the modern world. Mr. Studebaker, the automobile manufacturer from South Bend, proudly accepted to be Chairman of the venture.

That spring, a dozen workers set about clearing the southern end of the Assembly grounds. They removed thick underbrush and marked off an acre for each ward. They installed street signs and erected a huge tent at the entrance to the camp. They graded and rolled an athletic field and brought in sand for a beach. They installed piers for fifty rowboats. They built a mammoth toboggan chute down which wooden sleds crashed into the lake. Mr. J. G McGee delivered an authentic Columbia Voting Machine that his company manufactured. The new-fangled machine had survived the “voting machine war” a few years before and was recognized as an infallible invention.

By the end of June, the only thing missing was boys.

On July 26, 1907, a sunburned and dusty contingent arrived on bicycles from Marysville, Ohio, after a one hundred and eighty mile adventure. The Huntington delegation hiked fifty miles to Boy City. A company of twenty-five made their way on foot from Wabash. Hundreds more arrived by train. Uniformed regiments of the Indiana Boys Brigade marched onto the Assembly grounds with Springfield rifles. Under the command of Capt. Biddle, they set up pickets to keep gawkers out. By order of Judge Brown, Boy City fell under military rule until after elections in which the boys overwhelmingly chose fifteen-year-old Frank Abbott of Goshen as the first mayor of Boy City. A watermelon feast followed the ceremonial induction of Abbott and the newly elected city council members.

Before the historic first encampment at Boy City pulled up stakes, the Muncie Evening Register reported its astounding success. Judge Brown had delivered on his promises, and the Winona Assembly wanted to make Boy City a permanent Chautauqua event.

“In a few years,” Judge Willis boasted, “every state will have its own Boy City.” In fact, Judge Brown let slip a plan for a European tour with a group of fifty boys slated for the following year. This news sent a thrill of excitement through the ranks.

More glowing reports poured out of Boy City the second year, giving account of yet another spectacular season. However, in May 1909, two months before the third annual encampment, Sol Dickey issued a surprise press release to the effect that the Winona Assembly had severed all ties with Judge Willis Brown.

When Brown pitched his elaborate—and expensive—vision for Boy City in 1906, his audience did not know that Utah’s State Supreme Court was about to hand down a ruling regarding Brown’s supposed first juvenile court of Utah. Details about his credentials and his antics began circulating in 1907 when former associates set out to expose him as a fraud.

Initially, Sol Dickey defended his young colleague by explaining in a newspaper article that Judge Brown had purposefully legislated himself out of the court, which was Brown’s explanation of the matter. Over time, however, as complaints trickled in, doubts about Brown’s character plagued Dickey. It was the following letter from Judge Benjamin Lindsey that warranted decisive action.

Mr. Dickey,

I am writing concerning an impostor in your midst in the person of Judge Willis Brown. I have no desire to injure the man. I confess I was taken in by him myself several years ago. The truth of the complicated matter is that the man is not a lawyer, and the court he presided over in Salt Lake had no legal standing. I’ve learned that he has bragged of the thousands of dollars he has made on the lecture circuit calling himself a judge and that he jokes of the ease with which he foists himself upon the public. I am not aware of any unscrupulous conduct at Winona Lake. However, you should be warned that he is not an honest man.

For all of his talk of drawing thousands of boys to Winona, Judge Brown’s Boy City drew only seven hundred the first year and five hundred the second year. Press releases celebrated the camp’s successes, but the balance sheet told a different story. The investment was not paying for itself as Brown had promised. Besides the disappointing budget shortfall, Brown’s methods of overseeing the boys had sparked a number of embarrassing episodes.

The first summer, when two members of the Indiana Boys Brigade were on night patrol, one of the boys accidentally shot the other in the face at close range. The rifle fired a blank that left the other boy with serious but non-life threatening wounds. Mr. Dickey had been called out of bed and had rushed to the scene. The injured boy rode the train home where doctors intervened to save his eyesight. Papers carried the story, and the Assembly responded by actively assuring parents that Boy City was safe for their sons.

On another day, members of the Boys Brigade pursued the milkman through the Assembly grounds all the way to the Winona Hotel, firing volleys (more blanks, thank goodness) before taking the poor fellow into custody. The disturbance brought the sheriff to the camp with the warning that if another gun were fired, everyone would be arrested. The following morning, the boys found themselves without fresh milk and ice, and the Winona Assembly found itself the subject of another embarrassing news story.

Similar problems mounted the second season when over one hundred boys failed to show up—yet another financial loss. And then there was the bizarre circus with a host of strange sights including a sideshow featuring a five hundred-pound “woman” played by a two hundred-pound boy in a dress with a plunging neckline, red lipstick and a blonde wig made from straw. The Assembly’s leaders found the acclaimed circus a considerable deviation from the original vision of a well-run municipality.

Mr. Dickey got up from his desk and walked to the window. The steamer City of Warsaw chugged across the lake. Exhilarated passengers waved to the crowds on the beach. Rowboats bobbed in the steamer’s wake. He thought of the hundreds of patrons filling the auditorium for the afternoon concert and imagined the Shakespeare cast rehearsing for its next performance. He recalled the glamorous floats from Venetian Night the week before when magnificent creations coasted along the canal leaving spectators awestruck.

A barely perceptible smile reflected on the windowpane. Dickey held in his hand the evidence he needed to rid Winona of this huckster once and for all. He tucked the letter into his breast pocket, grabbed his hat and walked in the direction of Willis Brown’s summer cottage.

Boy City operated on an ever-diminishing scale for the next several years. Enthusiastic headlines announcing teenage mayoral candidates disappeared from local papers. Bold forecasts for thousands of boys descending on Winona Lake fizzled. The boys’ bank, grocery store and post office closed for good. An unnatural quiet enveloped the wooded hills. It hovered above the deserted athletic field and snaked its way to the water’s edge to linger among forlorn boat piers. Melancholy waves lapped the desolate beach.

In the summer of 1916, Boy City was recalled to life when the “Witter boys” arrived in Winona Lake. John Witter, a sincere, soft-spoken man and superintendent of the Chicago Boy’s Club, led a band of seventy-five ragtag boys through the Winona Assembly to the camp. Bystanders smiled at the heartwarming procession on its way to founding what would become a lasting model municipality.

Mornings began with reveille. A shrill trumpet signaled an early swim, followed by a flag raising ceremony and then a feast of eggs, pancakes, bacon, fruit and cool buttermilk. The Witter boys—a picture of America’s melting pot—learned to bait a hook and row a boat. They enjoyed swimming and diving lessons. Youth from a congested, hectic metropolis waded into Cherry Creek to catch bullfrogs and snapping turtles. They picked raspberries and mulberries and learned to differentiate between oaks, elms, pines and maples. For ten blissful days, boys from impoverished families worked a vegetable garden and gathered eggs from a chicken coop. Nature studies brought them into close contact with blue herons, red hawks, barred owls, warblers and finches. Locals pitched in by generously providing barrels of apples, fresh baked cookies and canned goods. Women’s sewing circles got to work making new garments for the boys and patching tattered ones.

For the first time in their lives, this group of boys from different faiths experienced the magic of a campfire. Every night they gathered in a circle to share stories, sing hymns and say their prayers.

When it came time to return to Chicago, the boys marched in their new clothes across the Assembly grounds to the train station. Theirs was a parade of energetic youngsters lugging jars of wild berries, clutching leaf collections and hauling pet turtles and frogs in small wooden crates. Every boy’s pockets overflowed with an assortment of feathers, rocks, shells and sticks.

The Witter boys represented a mixture of races and creeds of underprivileged kids, often the sons of immigrants whose mothers and fathers worked in factories made busy by the onset of WWI in Europe. A sudden rise in juvenile delinquency at this time troubled John Witter, so he set about finding a respite for troubled boys roaming the streets of Chicago. His search had led him to Brown's abandoned Boy City on the southern edge of Winona Lake.

The first Boy City had ended precipitously with the termination of that infamous rascal Willis Brown. Nevertheless, Sol Dickey did not give up on the nation’s boy problem created by an increasingly industrialized America. In 1916, he welcomed John Witter, a man who had been raised on a farm. He brought the boys to Winona Lake and taught them to plow, plant and weed. He and his wife cared for the property and invested themselves in these youngsters.

A benefactor purchased Boy City from the Winona Assembly for the Chicago Boy’s Club to establish a “city” which endured for three generations and which brought thousands of disadvantaged boys to a wooded haven where they escaped the temptation of joining street gangs, interacted with nature, learned important life skills and enriched their spiritual lives.

Willis Brown proved to be a dishonest man, but for the sincere in heart, even the visions of a scoundrel can be turned into something wonderful.

0 notes

Text

An Unwanted Guest

“Typhoid?” The woman gasped and turned in horror to her husband standing beside her in a state of shock.

“I am so sorry to give you the news,” the doctor offered apologetically, looking from one parent to the other. “Your son’s symptoms were at first consistent with appendicitis, but I am certain now—” he halted. “It’s very serious."

The once buoyant, gregarious teenager lay on his bed in the classic typhoid state. His eyes half-opened, his body motionless, his color gone.

Mr. and Mrs. Pugh were spending the summer at their cottage in Winona Lake with their three sons. Mr. Pugh, a humorist, entertained sold-out crowds on the Chautauqua circuit, performing in Winona and other resorts in Indiana. The grim prognosis turned the joyous family tradition of vacations at the lake suddenly tragic.

The doctor gently explained to the parents that their son presented all of the symptoms of an advanced case of typhoid and that he suspected a perforated bowel.

“The contents of the bowel have escaped through a tear and spilled into his abdomen. He is raging with infection. We need to get him to the hospital for surgery if there is to be any hope of saving him.”

The grave tone rendered the stricken parents mute. They nodded their assent.

The anxious family—mother, father and brothers—stood to meet the doctor as he approached. His expression prepared them for more bad news. Richard was critical.

“I did what I could, but he is hemorrhaging.”

“What’s next?” The father’s frantic voice begged for a cure.

“Our only option is a blood transfusion,” the doctor said with some reluctance before adding, “I can’t promise anything.”

Mr. Pugh gave a pint of blood and then sank into despair when his son did not respond. Out of desperation, another transfusion was performed, this time drawing from one of the brothers. The Pugh’s hometown paper reported a slight improvement, but two days later, 17-year-old Richard succumbed to the dreaded typhoid fever.

When Richard Pugh fell ill in Winona Lake in July 1920, fear of an epidemic gripped the leaders at the Winona Assembly, for it had been a mere eighteen months since the Spanish flu had ravaged the newly established military training camp there.

Sol Dickey, Secretary of the Winona Assembly, spent much of 1918 negotiating a contract with the United States War Department to host a training camp in Winona Lake. The availability of dormitories and a vocational school made it an appealing location for the specialized training of draftees. Dickey traveled to Washington, and people from Washington traveled to Winona. They struck a deal, and on October 15, 1918, a thousand young men from every county in Indiana began arriving.

Trainload after trainload of enthusiastic Hoosier sons, eager to participate in the war in Europe, pulled into the station, each one greeted with the local version of pomp and circumstance: a thirty-two piece band and free cigars. A veteran of the Spanish-American War carried the American flag while ceremoniously leading groups to special interurban cars for transportation from the depot in Warsaw to the new camp two miles away on Winona Lake.

By the following morning, the camp had several cases of Spanish Influenza. The number swelled to one hundred and fifty within two weeks. At this time, schools and businesses throughout the state were already closed to prevent the spread of the pandemic. But World War I had not yet ended, and the United States government continued preparing its fighting force.

Over the next several weeks, infections surged. Nineteen men died. On November 23rd, just forty days after their celebrated arrival, the soldiers climbed back onto the interurban and journeyed south to Indianapolis. The camp at Winona Lake was officially abolished.

Although an investigation concluded that the Spanish flu arrived with the soldiers and that no fault lay with the Winona Assembly, the memory of that blighted experiment still haunted Mr. Dickey. When he first received word that the Pugh’s son was sick with typhoid, he worried that if the contagion spread, the Winona Assembly could be in for another disaster like that of 1918. To his relief, no one else contracted the disease.

The Pughs sued the Winona Assembly, pointing a finger at the beloved Studebaker Spring where their son had taken a drink a few days before the onset of his symptoms. Mr. Pugh alleged that spring water had been contaminated by a busted sewer main and accused the Winona Assembly of bearing responsibility. The Assembly could not prove that the water was not contaminated on the day that Richard Pugh drank from it. And even though no broken mains were detected, city officials decided to close all of the springs on the Assembly grounds after an inspection by Dr. Hurty of the Indiana Department of Health.

Thus it was that the tragic death of young Richard Pugh brought the passing of an era. The beloved springs whose water had once been bottled and sold, the source of cherished fountains preserved on so many postcards, the inspiration for the town’s original name, Spring Fountain Park, were now identified as a health hazard.

In a tragic twist, two months after the closing of the fountains, a typhoid epidemic swept through Winona Lake. Papers reported the death of three-year-old Sarah Taylor visiting Winona Lake with her father, a widower. The Indiana Department of Health sent Dr. Hurty to investigate after learning of several more cases. Hurty looked first at the water supply. Having established that it was not contaminated, he turned his attention to the local dairies.

Dr. Hurty was a veteran crusader against unsanitary dairy practices. He came down hard on dairies because the victims of bacteria-ridden milk were overwhelmingly children. He sought to expose those who increased their profits by diluting milk with water that, if contaminated, spawned disease. He was on a mission to put an end to milk tainted with worms, blood, pus, manure, and insects. Hurty preached pasteurization as a matter of public health, but in 1920, the vast majority of America’s children still consumed raw, unpasteurized milk.

Armed with these facts, Dr. Hurty launched a meticulous inspection of area dairies. When the results from the milk supply came back negative for typhoid bacteria, he tested employees and found the culprit. An asymptomatic deliveryman had unwittingly contaminated the milk on his wagon and set off an historic epidemic. Winona Lake saw forty cases of typhoid and the deaths of two children, Sarah and Billy. Neighboring Warsaw recorded similar numbers. One of the worst typhoid outbreaks in Indiana put an end to the sale of raw milk in Winona Lake when the city council passed an ordinance requiring the pasteurization of all milk delivered there. Warsaw did the same.

The Winona Assembly got to work advertising clean water and pasteurized milk to reassure the thousands of summertime visitors that they would be safe from the threat of typhoid fever. That promise proved true for the next two summers, the proverbial calm before the storm.

Thousands descended upon Winona Lake for ten days in June of 1925. On one of those days, Sunday the 7th, a dense crowd of thirty thousand swarmed the grounds. Eight thousand poured into the Billy Sunday Tabernacle filling it up to the doors. The overflow streamed onto the lawn and gathered around the amplifiers. Those that could took up positions at the windows to watch the service going on inside. Parked cars blocked the streets leaving drivers to fight their way through the stationary traffic jam. This was the annual Church of the Brethren Conference, and it drew an enormous response. Nothing but humanity as far as the eye could see!

June in Indiana is a fickle month. No one can be sure whether it will be cold or hot, wet or dry. Conference-goers rejoiced at an abundance of sunshine and warm temperatures. Sprinklers overcame the dry conditions, keeping the dust down and the lawns lush. Newly installed water fountains quenched the thirst of the multitudes rushing off to their meetings or savoring a leisurely stroll.

“We had a wonderful conference!” People exclaimed unanimously when the time came to say goodbye and head back to their home towns. They had come from all over the United States for several glorious days of meetings, reunions and religious services. The warm glow of good memories left little room to complain about a few inconveniences, like long lines at the restaurants, congested roads, water fountains that occasionally belched up dirty water, and a presumed bug that had caused painful stomach aches among dozens.

In the weeks that followed, several residents and Assembly employees contracted typhoid. The number reached thirty by the end of June. At the same time, Huntington County, forty miles southeast of Winona Lake, saw its own outbreak. A doctor attending those patients discovered that all had attended the big conference. He contacted the Indiana State Board of Health. Officials immediately dispatched an inspector to Winona Lake to investigate a possible epidemic.

News of more typhoid cases continued trickling in from among the Church of the Brethren congregations around the country.

As the number of typhoid cases climbed, so did the fatalities. Alma Williams, a widow and mother of three, passed away in Elgin, Illinois. Two sisters, Rose and Carrie, who attended the conference together, died three days apart. Fifteen-year-old Galen Neher had moved to Winona for a summer job. Upon his death, his grief-stricken mother hired a lawyer and threatened to sue the Assembly.

Certain now of an epidemic, the investigator turned his attention to finding the source. Several factors had to be ruled out. Had some among the conference attendees brought the disease with them? Was milk once again to blame? Were flies transmitting disease? Were any of the food workers asymptomatic carriers?

Upon debunking these theories, the investigator concentrated on stories of foul smelling water at the drinking fountains, the barber shop and in a few of the cottages. He visited an old cistern, condemned it and cited it as the source of the outbreak. He flushed and chlorinated the mains, after which he declared the water supply in Winona Lake as safe.

In response to the flurry of newspaper articles slamming the Assembly for the use of an old cistern, the company that supplied water to Winona adamantly defended its practices and demanded a second investigation.

A new inspector arrived to reevaluate the evidence. As a precaution, he ordered the vaccination of residents and visitors to protect against further spread.

The complaints of fetid water restricted the episodes to an isolated area and rendered the cistern theory highly improbable. Furthermore, the wells supplying the water did not test positive for enough bacteria to explain the virulent spread.

Then, an employee from the water company that was seeking to clear itself of responsibility happened to notice an inconsistency in the meter readings for three consecutive days in June when the numbers had gone lower instead of higher. This could mean only one thing. Water had flowed backward through the mains.

While the drinking water came from local wells, the sprinkler system and the public toilets drew water from the nearby canal into which residential sewers drained. By some act of very bad planning or sheer ineptitude, the public water and the canal water systems had been joined under the public toilets, separated only by a valve. When the pump at the canal broke down one fateful day in June, someone, whose identity was never learned, opened the valve to keep the toilets flushing properly. The pressure variance sent polluted canal water into the mains and straight to the water fountains, the barbershop and nearby cottages.

The health department ordered the sprinkler system to be shut down immediately and permanently since it was potentially spreading the contagion throughout the park. Health officials also mandated that Winona Lake install a modern sewage plant before its next summer season.

It’s unclear exactly how many people contracted typhoid in Winona Lake in June 1925. The town’s deadliest and last typhoid epidemic may have infected as many as one thousand, claiming at least thirty lives.

By the turn of the twentieth century, thousands of people visited Winona Lake every summer. They strolled along the water’s edge, weaved through shady paths, drank liberally from cool springs, and flocked to the hillside to watch the sunset. They swam, fished, picnicked and worshiped together year after year. The Winona Assembly prided itself in offering comfortable lodgings amidst peaceful surroundings. Its leaders sought the best talent and most articulate speakers to educate and inspire thronging visitors. However, typhoid, an unwanted guest, sneaked in and triggered six epidemics during the first thirty years of the Winona Assembly. When one considers the introduction of pasteurized milk, the closing of the iconic springs, emergency vaccinations, and the laying of a modern sewage system, it may not be an exaggeration to say that disease achieved as great an impact on Winona Lake as any convention held there.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Winona Lake, No Winona

Era un conocido hecho y lo había sido durante los últimos años, que el mayor parte del correo recibido en la pequeña oficina postal de Winona en Bass Lake en el Starke Condado por el administrador de correo Cary D. Chapman no era realmente dirigido a ninguna persona que vivía allí. Se pasó una gran cantidad de tiempo de regresar bolsa tras bolsa de cartas a sus remitentes o reenviarlos con desdén a la Oficina de Cartas Muertas. Ni sola una vez se quejo del trabajo extra. Por el contrario, recibió una gran cantidad de placer. “Eso es lo que esos carpetbaggers merecen para huirse con nuestro nombre,” se quejó. Nadie, y menos de todo el irascible Senor Chapman, podría haber previsto la cadena de eventos que él ponía en movimiento para crear sin darse cuenta, unas cuarenta millas de distancia, un nuevo pueblo que reclamaria para sí el orgulloso nombre de Winona Lake.

En algún lugar de Indiana en marzo del 1895, un distinguido hombre en su mediados de 30s caminó rápidamente hacia una estación de tren. Llevaba una cartera de cuero recortada con oro y llevaba un abrigo gris oscuro y un sombrero de fieltro con la signatura abolladura en el medio de la corona. Al entrar en la estación, se acercó al mostrador. Con una sonrisa cautivadora, le dijo al jefe de estación su destino. Habiendo recibido su boleto, se hizo a un lado. Metió la mano dentro del interior de la chaqueta y echó un vistazo a un reloj de bolsillo de oro fino. Volvió el reloj a su lugar y se quedó pensativo. El agobiado viajero dejó escapar un suspiro involuntario, y en un susurro bajo que nadie podía oír, murmuró, “Con qué rapidez nuestra suerte puede cambiar!” Sus pensamientos lo llevaron al enero anterior en ese glorioso domingo cuando el se paró en la nueva iglesia presbiteriana—anteriormente el salón local de baile—y anunció a una delirante multitud sus planes para el establecimiento de un Indiana Chatauqua.

Una multitud considerable de escalofríos presbiterianos pisoteado del frío, golpeando la nieve de sus botas y castañeteando de emoción mientras que compartir lo que poco él o ella había oído del servicio especial del Rev. Dickey. El ministro había hecho el viaje de Indianapolis a encender un fuego debajo de los locales que se quemarían caliente durante todo el invierno y en la primavera.

“Bass Lake ha sido elegido por los presbiterianos de Indiana para ser el hogar de la propia Chatauqua de Indiana!”

Todos en la sala sabían lo que eso significaba y ofreció un aplauso entusiasto. El anuncio incluso generó unos gritos y silbidos. El movimiento de Chatauqua había surgido en Nueva York diez años antes y había extendido a la región central y otras partes del país. En el lago de Chautauqua, los Metodistas ofrecian vacaciones de verano que consistían de entretenimiento cultural y educativo. Los programas incluyeron maestros, músicos, predicadores, showmen, oradores populares y pensadores. Lo que el Rev. Dickey describió esa manana se consideró un Chautauqua muy mejorado, ya que se apartó de las formas liberales de los Metodistas a uno de acuerdo con las creencias representadas entre los reunidos.

“La Winona Asamblea, nuestro nombre Chautauqua aquí en Bass Lake, presentará una conferencia de Biblia además de un programa de la más alta calidad inspirado por la Madre Chautauqua, nuestro predecesor en Nueva York.”

Un rugido de aplausos sacudió las vigas, y el reverendo sintió cerca de bailar.

“Imagina esta humilde estructura transformada en una Hermosa iglesia presbiteriana. Imagina un salón de música, edificios universitarios, y un gimnasio rodeandonos.” Su sonora voz, sonrisa cautivadora y encanto natural combinaron para persuadir.

“Pueden ver unos pocos miles de visitantes dando vueltas sobre jardines de flores impresionantes y disfrutando de la dulce y refrescante brisa del lago?” Hizo un gesto hacía una ventana. Los terrenos pueden haber estado cubiertos de nieve y el lago congelado, pero la gente vio vívidamente lo que pintó con palabras.

“?Pueden Uds. imaginarse a unos pocos miles de personas apresurandose para asistir un concierto? Ellos verterán este verano de todo Indiana para escuchar nada menos que el presidente anterior Benjamin Harrison!”

Sus oyentes jadearon ante la idea de tal espectáculo. Ellos se pusieron de pie como una y aplaudieron de sus manos en una ensordecedor declaración de apoyo.

Al final del servicio, los alegres congregados se quedaron para afirmar el apoyo de este honorable visionario. Ellos brillaron. Profetizaron un gran éxito. Dieron las gracias al reverendo para la selección de Bass Lake para poner en marcha un nuevo tipo de Chautauqua.

Era de marzo, ahora, y si el suelo se había comenzado a descongelar, las negociaciones con los funcionarios del condado se habían congelado. Relaciones heladas pusieron en peligro la gran inauguración de la Winona Asamblea.

Tales eran los pensamientos del preocupado caballero en la estación de tren cuando sintió un suave toque en el hombro. Se dio la vuelta y miró a los ojos de un hombre cercano a él en edad y de considerablemente distinguido porte. Su abrigo negro de doble botonadura tenía botones cubiertos de tela. Una cinta de seda destacó su elegante sombrero de copa negra. Su mano izquierda sostenía un bastón de madera muy pulido con una talla de marfil adornado en su cabeza.

El desconocido extendió su mano. El hombre correspondió.

“?Tengo el honor de conocer al Rev. Dickey?” Él dijo con un agradable y suave acento alemán, y anadió, “Soy J.E. Beyer.”

Ese nombre sonó una campana.

“Señor Beyer, es un placer,” Rev. Dickey respondió con toda la dignidad de un hombre de su estatura.

J.E. Beyer fue uno de un trio de hermanos que habían emigrado de Alemania y se establecieron en Indiana como mayoristas en productos lácteos y aves de corral. Poseían y operaban Spring Fountain Park. En los últimos años, habían cambiado las palabras “el lugar de reunión” para “asamblea” cuando decidieron llevar una versión pequeña de Chautauqua a Indiana.

Los dos hombres entraron en el tren juntos, dirigido por el Sr. Beyer que vio un asiento vacante e invitó a Rev. Dickey unirse a él. El Sr. Beyer no perdió el tiempo en llegar al punto.

“He estado siguiendo su esfuerzo para abrir un Chautauqua presbiteriano en Bass Lake.”

“Entonces, usted es consciente de que ciertos oficiales del condado y del ferrocarril están jugando con nosotros,” respondió el reverendo. “Estamos a la espera de miles de visitantes. Una línea de tren debe venir todo el camino hasta los terrenos de la Asamblea, o de lo contrario los viajeros quedaran varados varias millas de distancia. Sin embargo, los oficiales se niegan a actuar en esta condición no negociable.”

Él casi esperaba al Sr. Beyer hacerle preguntas sobre los detalles y proponer una solución. En cambio, el empresario decidido tomó al reverendo por sorpresa con una oferta.

“Estoy seguro, Rev. Dickey, que Ud. está conciente de nuestras propias instalaciones. Tenemos todo lo que necesita en Spring Fountain Park para abrir su Chautauqua a tiempo, y estamos dispuestos a vender.”

Rev. Dickey se quedó atónito por un momento. El Sr. Beyer dejó que sus palabras trascendentales se hunden mientras que trazar las rañuras delicadas de marfil en su bastón.

Cuando volvió a hablar, el Sr. Beyer describió un hotel de primera clase convenientemente ubicado frente a la estación de trenes. Se jactaba de un auditorio que podía albergar dos mil, meticulosamente cuidadas jardines de flores, varios manantiales naturales, y una oficina de correos. La lista continuó, ya que los hermanos habían pasado diez años y $125,000 desarrollando el parque.

Los otros pasajeros no podían oír lo que pasó entre los dos, ni podían mirar hacía otro lado. El intercambio animado les proporcionó bienvenida entretenimiento. Los hombres iban de episodios de abundante risa a largos tramos de diálogo intenso como si se estaban formulando una gran idea que cambiaría el mundo. “Puede muy bién ser que estamos en presencia de la historia”, un pasajero se le oyó decir.

En la parada del tren, el Rev. Dickey abrazó al Sr. Beyer y partió con un semblante alegre y un jubiloso andar.

La Winona Asamblea inauguró el julio 1 de 1895. Una multitud de comunicados de prensa habló de una maravillosa Chautauqua y Conferencia de Biblia en Eagle Lake a dos millas de Warsaw, Indiana. El inquebrantable liderazgo del Rev. Dickey había visto a la junta y los accionistas a través de una tormenta de crisis; verano trajo la cosecha de luchas recientes. Sin embargo, un problema emergió, un molesto detalle del fallido intento de establecer en Bass Lake.

El nombre de Winona que los presbiterianos habían legalmente asumido por su Chautauqua había venido de un pueblo en Bass Lake y fue también el nombre de la oficina de correos se encuentra allí. Cuando la Asamblea se retiró y se instaló en su lugar en Eagle Lake, residentes de Winona en Bass Lake se indignaron. Y cuando el problema del correo surgió, cavaron y se negaron a ceder ni una pulgada, su fiel administrador de correo a la cabeza.

Mientras el Rev. Dickey anunciaba que la correspondencia se dirigía a Eagle Lake, la gente suponía que la Winona Asamblea estaba ubicada en un lugar llamado Winona, que había sido el plan original. La confusión resultó en cientos y cientos de cartas—no solo al Rev. Dickey, sino también a invitados oradores, músicos, maestros y aquellos que pasaron el verano en los terrenos-- dirigiéndose al Administrador Chapman en Winona en Bass Lake, quien se aseguró de que no llegaron a sus destinatarios.

El problema se volvió crítico en la primavera de 1897 después de que el incipiente Chautauqua se ganó el derecho de organizer la prestigiosa Anual Presbiteriana General Asamblea. La oportunidad fue tanto un honor como una enorme empresa, pero la debacle de correo seriamente los obstaculizó las preparaciones. John Studebaker, un accionista de la Winona Asamblea y fundador de la Studebaker Corporación de Automóviles, escribió una carta al Presidente McKinley insistiendo en que algo se haga. Muchos presumieron que el asunto se resolvería en cuestión de días.

No lo fue.

En enero de 1898, la oficina de correos de la Eagle Lake legalmente cambió su nombre a la Oficina de Correos de Winona Lake. A pesar de este intento de aclarar la confusión, la gente continuó dirigiendose al correo a Winona, Indiana, suministrando un flujo constante de correo imposible de entregar a la oficina de correos de Bass Lake. Rev. Dickey fue hasta el punto de poner un anuncio en los periódicos con la directiva para dirigir la correspondencia a “Winona Lake, no Winona.”

El problema persistió.

Según las leyes del correo, dos oficinas de correo en el mismo estado no podrían compartir el mismo nombre, y la única persona con la autoridad para reparar el desorden era el presidente de los Estados Unidos. Mientras tanto, innumerables cartas destinadas a la oficina de correos de Winona Lake terminaron en las manos del obstinado jefe de correos de la Oficina de Correos en Bass Lake.

El diez de agosto de 1903, el Logansport Daily publicó la historia de los dos Winonas: “Hay millones de personas en el nombre para que una corporación religiosa está luchando contra el jefe de correos en Winona en el Starke County,” comenzó el artículo. Continuaba decir como el jefe del correos de Winona, Cary D. Chapman, caracterizado cómo un patriota y un héroe de las guerras Civil, Indio y Mexicana, estaba defendiendo el derecho de su oficina de correos conservar su nombre.

Según el Daily, el noventa por ciento de las personas que se dirigieron cartas destinados a la Oficina de Correos de Winona Lake dejó la palabra “lake.” Como resultado, su correspondencia fue a Winona en el Starke County, “la única oficina en el estado,” el periódico sostenía, “legalmente reclamando ese nombre.”

El Presidente Theodore Roosevelt, quien cree Chautauqua era la cosa más Americana de America,” envió una carta al Director General de Correos. Él, a su vez, envió investigadores postales a las dos oficinas de correos en guerra. El informe de los investigadores indentificó el Correos de Winona Lake como sirviendo mucho más ciudadanos que el otro Winona, y castigó a su jefe de correos por su parte en frustrar la entrega de correo de los Estados Unidos por un tecnicismo. En abril de 1905, el Sr. Chapman perdió su lucha por el nombre y su trabajo. La oficina de correos en Winona en Bass Lake pasó a llamarse Cobbler Station, llevando el nombre de su nuevo administrador de correos.

Era un establecido hecho a pesar de lo que reportaron los periódicos, que el Rev. Dickey pretende abrir el Chautauqua en las afueras del bucólico Winona en Bass Lake en Starke County. Es por ello que la Winona Asamblea fue legalmente constituda con ese nombre en febrero de 1895. Cuando ciertos funcionarios levantaron obstáculos, J.E. Beyer intervinó con una oferta que nadie más podía igualar. El resultado fue el problema perenne de correo redireccionado a manos de Sr. Chapman que obligaron una confrontación que requiere la intervención de un Presidente. La lucha del Rev. Dickey para traer una Chautauqua a Indiana lo encontró envuelto en un conflicto con una oficina de correos rival, y fue Winona Lake, no Winona, que surgió el vencedor.

Translation by Gail Rogge Merriman

Agradecimiento espcial a: Al Disbro, Winona Lake, IN; Schricker Main Library, Knox, IN; Winona History Center at Grace College, Winona Lake,IN

0 notes

Text

Winona Lake, Not Winona

It was a known fact, and it had been for the last several years, that most of the mail Postmaster Cary D. Chapman received at the tiny Winona Post Office at Bass Lake in Starke County was not really intended for anyone who lived there. He spent a great deal of time returning bag after bag of letters to their senders or forwarding them disdainfully to the Dead Letter Office. Not once did he complain about the extra work. Rather, he received a great deal of pleasure from it. “That’s what those carpetbaggers get for running off with our name,” he grumbled. No one, least of all the irascible Mr. Chapman, could have foreseen the chain of events he set in motion to create unwittingly, some forty miles away, a new town that would claim for itself the proud name of Winona Lake.

Somewhere in Indiana in March of 1895, a distinguished man in his mid-30s walked briskly toward a train station. He carried a leather, gold-trimmed portfolio and wore a dark gray overcoat and a homburg hat with the signature dent down the middle of the crown. Upon entering the station, he approached the counter. With an engaging smile, he told the stationmaster his destination. Having received his ticket, he stepped aside. He reached inside of his coat and glanced down at a fine gold pocket watch. He returned the timepiece to its place and became pensive. The burdened traveler let out an involuntary sigh, and in a low whisper that no one could hear, he muttered, “How quickly our fortunes can change!” His thoughts took him back to the previous January on that glorious Sunday when he stood in the new Presbyterian church—formerly, the local dance hall—and announced to a delirious crowd his plans for the establishment of an Indiana Chautauqua.

A sizable crowd of shivering Presbyterians tramped in from the cold, knocking the snow from their boots and chattering with excitement as each shared what little he or she had heard about Rev. Dickey’s special service. The minister had made the trip from Indianapolis to light a fire under the locals that would burn hot all winter long and into spring.

“Bass Lake has been chosen by the Presbyterians of Indiana to be the home of Indiana’s own Chautauqua!”

Everyone in the room knew what that meant and offered up enthusiastic applause. The proclamation even generated a few whoops and whistles. The Chautauqua movement had sprung up in New York ten years before and had spilled over into the Midwest and other parts of the country. At Chautauqua Lake, the Methodists offered summer vacations comprised of cultural entertainment and education. Programs featured teachers, musicians, preachers, showmen, popular speakers and thinkers. What Rev. Dickey described that morning was considered a Chautauqua much improved, for it departed from the liberal Methodist ways to one in keeping with the beliefs represented among those gathered.

“The Winona Assembly, our Chautauqua name here at Bass Lake, will feature a Bible conference in addition to a program of the highest quality inspired by Mother Chautauqua, our predecessor in New York.”

A roar of applause shook the rafters, and the reverend felt close to dancing.

“Imagine this humble structure transformed into a beautiful Presbyterian church. Picture a music hall, college buildings, and a gymnasium surrounding us.” His sonorous voice, engaging smile and natural charm combined to persuade and exhilarate the people.

“Can you see a few thousand visitors milling about breathtaking flower gardens and luxuriating in the sweet, refreshing lake breeze?” He gestured toward a window. The grounds may have been snow-covered and the lake frozen, but the people saw vividly what he painted with words.

“Can you picture a few thousand guests rushing about to attend a concert? They will pour in this summer from all over Indiana to hear none other than former President Benjamin Harrison!”

His listeners gasped at the idea of such a spectacle. They jumped to their feet as one and clapped their hands in a deafening declaration of support. At the end of the service, the cheerful congregants stopped to affirm the support of this honorable visionary. They beamed. They prophesied a grand success. They thanked the reverend for choosing Bass Lake to launch a new kind of Chautauqua.

It was March, now, and though the ground had begun to thaw, negotiations with county officials had frozen over. Icy relations jeopardized the grand opening of the Winona Assembly.

Such were the thoughts of the preoccupied gentleman in the train station when he felt a gentle tap on his shoulder. He turned around and looked in the eyes of a man close to him in age and of considerably distinguished deportment. His black, double-breasted coat had fabric-covered buttons. A silk ribbon set off his elegant, black top hat. His left hand held a highly polished wooden walking stick with an ornate ivory carving at its head.

The stranger extended his hand. The man reciprocated.

“Have I the honor of meeting Rev. Dickey?” He said with a pleasant, mellow German accent, and added, “I am J.E. Beyer.”

That name rang a bell.

“Mr. Beyer, it’s my pleasure,” Rev Dickey replied with all the dignity of a man of his stature.

J. E. Beyer was one of a trio of brothers who had emigrated from Germany and settled in Indiana as wholesalers in dairy and poultry. They owned and operated Spring Fountain Park. In recent years, they had traded the word “resort” for “assembly” when they decided to bring a small version of Chautauqua to Indiana.

The two men entered the train together, led by Mr. Beyer who spotted a vacant bench seat and invited Rev. Dickey to join him. Mr. Beyer wasted little time in getting to the point.

“I’ve been following your effort to open a Presbyterian Chautauqua at Bass Lake.”

“Then, you are aware that certain county and railroad officials are toying with us,” the reverend replied. “We are expecting thousands of visitors. A train line must come all the way to the Assembly grounds, or else the travelers will be stranded several miles away. Yet, officials refuse to act on this non-negotiable condition.”

He half expected Mr. Beyer to quiz him on the details and propose a solution. Instead, the determined businessman caught the reverend off guard with an offer.“

I am sure, Rev. Dickey, that you aware of our own facilities. We have everything you need at Spring Fountain Park to open your Chautauqua on time, and we are willing to sell.”

Rev. Dickey sat stunned for a moment. Mr. Beyer let his momentous words sink in as he traced the delicate ivory grooves on his cane.

When he spoke again, Mr. Beyer described a first class hotel conveniently located across from the train depot. He boasted an auditorium that could seat two thousand, meticulously groomed flower gardens, several natural springs, and a government post office. The list went on, for the brothers had spent ten years and $125,000 developing the park.

The other passengers could not hear what passed between the two, neither could they look away. The animated exchange provided them welcome entertainment. The men went from episodes of hearty laughter to extended stretches of intense dialogue as if they were formulating a grand idea that would change the world. “It may very well be that we are witnessing history,” one passenger was heard to say.

At the train stop, Rev. Dickey embraced Mr. Beyer and departed with a cheerful countenance and jubilant gait.

The Winona Assembly opened on July 1, 1895. A multitude of press releases told of a wonderful Chautauqua and Bible Conference at Eagle Lake two miles from Warsaw, Indiana. Rev. Dickey’s unwavering leadership had seen the board and stockholders through a storm of crises; summer brought forth the harvest borne of recent struggles. However, a problem surfaced, a pesky detail from the failed attempt to establish at Bass Lake.

The name Winona that the Presbyterians had legally assumed for their Chautauqua had come from a village at Bass Lake and was also the name of the post office located there. When the Assembly pulled out and settled instead at Eagle Lake, residents of Winona at Bass Lake were indignant. And when the problem of the mail arose, they dug in and refused to give an inch, their faithful postmaster leading the way.

While Rev. Dickey advertised that correspondence be addressed to Eagle Lake, people presumed the Winona Assembly was located at a place called Winona, which had been the original plan. The mix-up resulted in hundreds and hundreds of letters—not just to Rev. Dickey, but guest speakers, musicians, teachers, and those spending the summer at the grounds—going to Postmaster Chapman at Winona on Bass Lake who ensured they did not reach their intended recipients.

The problem became critical in the spring of 1897 after the fledgling Chautauqua won the right to host the prestigious Annual Presbyterian General Assembly. The opportunity was both an honor and an enormous undertaking, but the mail debacle seriously hampered preparations. John Studebaker, a stockholder of the Winona Assembly and founder of the Studebaker Automobile Corporation, wrote a letter to President McKinley insisting something be done. Many presumed that the matter would be settled in a matter of days.

It wasn’t.

In January 1898, the Eagle Lake Post Office legally changed its name to Winona Lake Post Office. Despite this attempt to clear up the confusion, people continued to address mail to Winona, Indiana, supplying a steady stream of undeliverable mail to the post office on Bass Lake. Rev. Dickey went so far as placing an ad in the papers with the directive to address correspondence to “Winona Lake, not Winona.”

The problem persisted.

According to postal regulations, no two post offices in the same state could share the same name, and the only person with the authority to sort out the mess was the President of the United States. In the meantime, innumerable letters intended for the Winona Lake Post Office wound up in the hands of the obdurate postmaster of the Winona Post Office at Bass Lake.

On August 10, 1903, the Logansport Daily broke the story of the two Winonas: “There are millions in the name for which a religious corporation is fighting against the postmaster at Winona in Starke County,” the article began. It went on to tell how Winona’s postmaster, Cary D. Chapman, characterized as a patriot and a hero of the Civil, Indian and Mexican wars, was defending the right of his post office to retain its name.

According to the Daily, ninety percent of the people who addressed mail intended for the Winona Lake Post Office left off the word “lake.” As a result, their correspondence went to Winona in Starke County, “the only office in the state,” the paper argued, “lawfully claiming that name.”

President Theodore Roosevelt, who believed Chautauqua was “the most American thing about America,” sent a letter to the Postmaster General. He, in turn, dispatched postal investigators to the warring post offices. The investigators’ report identified the Winona Lake Post Office as serving far more citizens than the other Winona and punished its postmaster for his part in foiling the delivery of U. S. mail on a technicality. In April 1905, Mr. Chapman lost his fight for the name and his job. The post office in Winona at Bass Lake was renamed Cobbler Station after its new postmaster.

It was an established fact, despite what the newspapers reported, that Rev. Dickey intended to open the Chautauqua on the outskirts of bucolic Winona at Bass Lake in Starke County. That is why the Winona Assembly was legally incorporated by that name in February 1895. When certain officials threw up obstacles, J.E. Beyer stepped in with an offer no one else could match. The result was the perennial problem of rerouted mail at the hands of Mr. Chapman that forced a confrontation requiring the intervention of a sitting President. Rev. Dickey’s fight to bring a Chautauqua to Indiana found him embroiled in a conflict with a rival post office, and it was Winona Lake, not Winona, that emerged the victor.

Special thanks to: Al Disbro, Winona Lake, IN; Schricker Main Library, Knox, IN; Winona History Center at Grace College, Winona Lake,IN

1 note

·

View note

Video

#geode as I found it. #winonalake #myindiana #kosciuskocounty #indianadnr https://www.instagram.com/p/B2j9o6oHIFk/?igshid=1uf459wlpnatu

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

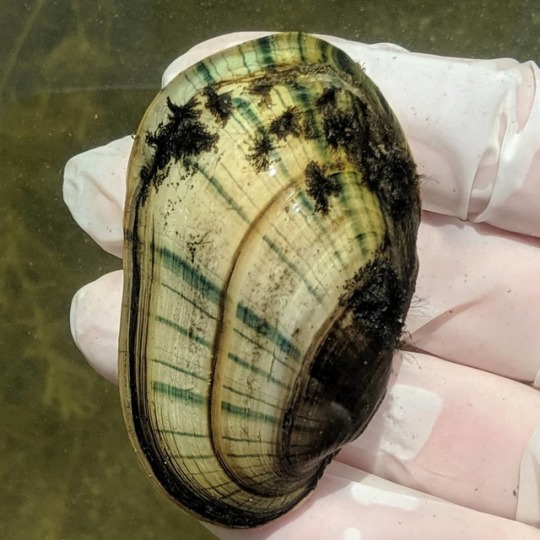

Happened to find this beauty under the sand. Don't worry! This is an underwater shot! It's safe'n sound. #winonalake #myindiana #kosciuskocounty (at Winona Lake, Indiana) https://www.instagram.com/p/B2h0WkcjyxY/?igshid=7970js7fqmgb

1 note

·

View note

Photo

A rock full of brachs! #brachiopod #winonalake #myindiana #kosciuskocounty https://www.instagram.com/p/B2hQ99EjGQO/?igshid=j8j8b5kk4cw2

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Another fascinating #coral design. #winonalake #myindiana #kosciuskocounty #fossils https://www.instagram.com/p/B2fpIe3jZqO/?igshid=jdjwz5xiu2tq

0 notes

Photo

#Silurian #Pentamerid (#brachiopod ) #steinkern from #winonalake #myindiana #kosciuskocounty (at Winona Lake, Indiana) https://www.instagram.com/p/B2dC1iYDFTc/?igshid=1kdgzfvaitvw1

1 note

·

View note

Photo

This is Cherry Creek! #winonalaketrails #winonalake #myindiana #kosciuskocounty (at Winona Lake, Indiana) https://www.instagram.com/p/B2YD6jQD50x/?igshid=14gdq7hwa6nzj

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Strangely symmetrical. #catsoninstagram #winonalake #indiana #cats https://www.instagram.com/p/B2YDeRaDoEO/?igshid=8v4udxhzp6xk

0 notes

Photo

A bouquet of #coral from #winonalake #myindiana #indianadnr https://www.instagram.com/p/B2VQodOjmxl/?igshid=13uk0o625bwd7

1 note

·

View note

Video

#monarchbutterfly emerges. #winonalake #natureindiana https://www.instagram.com/p/B2T7rHLjH5L/?igshid=1g60vrnsid4bq

0 notes

Photo

Just now #monarchbutterfly (at Winona Lake, Indiana) https://www.instagram.com/p/B2S2M60DwcT/?igshid=1w4kx47n1upex

0 notes

Photo

Day 12 in the #chrysalis #winonalake #natureindiana (at Winona Lake, Indiana) https://www.instagram.com/p/B2R7i9lDHYr/?igshid=3j4nlkxhj4xz

0 notes

Video

#treefrog #winonalaketrails #winonalake #indiananature (at Winona Lake, Indiana) https://www.instagram.com/p/B2Rq9j9jAOx/?igshid=1jjpjyb30swkw

0 notes