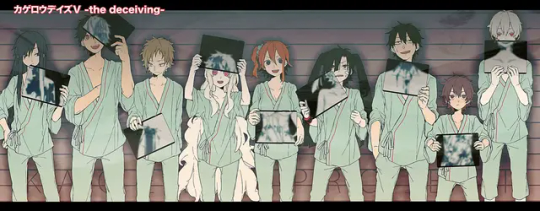

#This image is so charming yet eerie. Each pose has so much character! And for half of them it's “Teehee look at my horrible wounds”

Text

I know we're too early into Milgram's "so are the prisoners dead or not?" plotline for this, but since it looks like they're doing death-themed illustration for the fourth anniversary, you know what would be really cool?

The Milgram version of this Kagerou Project image:

Slightly spoilery KagePro context:

In KagePro all the main characters died and came back to life. The X-rays show the cause of death.

#Even the background reminds me of Undercover#I think paralleling the Undercover shots of them killing Es/their victims is more likely if they decide to pull something like this#But honestly those aren't very pretty. It's all black and red with barely any gradients... Just undetailed silhouettes...#I know that's the idea but still.#This image is so charming yet eerie. Each pose has so much character! And for half of them it's “Teehee look at my horrible wounds”#That's exactly how Yuno and Mahiru would do it tbh. I'd like to say Mikoto too but in official art he always looks confused. Maybe T2 Muu#milgram

31 notes

·

View notes

Link

They all start the same way: a few minor chords from a pipe organ, maybe a quick plug for Bromo-Seltzer or some other apothecary’s helper no longer in circulation — and then the creak.

It is the creakiest creak to have ever creaked, so drawn-out and borderline polyphonic that it could be mapped on a musical staff. Doors, even those leading to dank candlelit basements in which creepy bards wait with tales of the macabre, do not make this much noise in real life. (And that’s true; the creaking sound effect was achieved with a rusty swiveling chair. Pity the poor self-starting staffer who once oiled the makeshift instrument under the impression that he was helping out.)

But that’s just the order of the day on The Inner Sanctum Mystery, where there’s always a chill in the air, black cats yowl at the full moon, and no hinge keeps quiet.

Spun out from Simon & Schuster’s series of cheap paperbacks and then spun out once more into a six-picture series of feature films in the ’40s, the title gained the most prominence as a radio serial running 526 episodes from 1941 to 1952. Creator Himan Brown struck the same chord with audiences that Rod Serling would continue to clang all throughout the 1960s on The Twilight Zone, attaining impressive longevity through an infinitely renewable formula and the public’s unslakable thirst for fear.

Brown cohesively bound the many installments of this radio anthology by sticking with a consistent structure and tone befitting the morbid subject matter. A vampy host brought over from the Broadway stage (Raymond Edward Johnson, at first, then Paul McGrath from 1945 onward following Johnson’s enlistment in the war effort) would ham it up as he introduced the night’s diversion with florid language that would make Edgar Allan Poe proud.

Then followed an account of danger and suspense, playing up atmosphere and tension over gutbucket descriptions of gore, erring on the side of “spooky” rather than “horrifying.” These punctuated by occasional appearances from the schoolmarmish Lipton Lady, come to shill for sponsored tea and tut-tut the twisted little deviants who tuned in.

The narrator’s raconteurish presence set the scene as an act of yarn-spinning, a framing device harkening back to the scary-story form’s beginnings in the oral tradition. By creating this familiar cast of characters and an accompanying sense of communal gather-round-children experience, the Sanctum established itself as a place anyone could go to get scared out of their wits in the comfort of their own home.

While some episodes dove into the supernatural (to wit: “The Horla,” in which Paul Lukas contends with an invisible demon borrowed from an old French novella), they more frequently landed in an earthbound, Hitchcockian register. With all the gravitas that the sonorous cast could muster, they emphasized a human element among the violence, illustrating the ease with which jealousy, arrogance, or anger can drive a person to homicidal extremes.

All that each half-hour segment needed was a sturdy hook on which it could hang puns, pulpy pleasures, and purple prose; hubristic would-be masterminds plotting their perfect crime, average Joes stalked by unseen predators, lovers losing their senses in fits of feverish passion.

The dark side of the FM dial provided a playground for some of the era’s most lauded talent to cut loose, and launched careers for a handful of future stars. Because the Sanctum’s signature fusion of lurid content and arch humor toeing the line of camp offered many thespians a reprieve from a diet of soft-focus melodramas and dignified theatre work — not to mention a quick check — it attracted the cream of the day’s crop.

Silver screen monster-men such as Bela Lugosi and Boris Karloff were regular fixtures on the airwaves, the invisible man Claude Rains showed up for “The Haunting Face” (an episode now preserved by the Library of Congress) and two years out from Citizen Kane, Orson Welles dropped in to provide vocals for “Death Strikes the Keys.” Helen Hayes and Mary Astor set a course for the scream queens of the ’70s with their earsplitting terror, and even Frank Sinatra lent his velvety baritone to “The Enchanted Ghost.” For audiences in the ’40s, listening felt like attending a swinging costume party with all their favorite celebrities.

For listeners in 2018, however, the Sanctum and its library of nightmares live on as a totem of nostalgia for a bygone era, both of horror and audio media.

The Inner Sanctum Mystery took me unawares on — when else? — a dark and chilly night. During the final hours of an October day’s road trip with a friend, we were scanning the FM dial when an eerie shriek burst onto the radio and caught our attention. After about 20 rapt minutes, we learned that a local affiliate liked to treat Long Islanders to some vintage frights when the according season rolls around.

Though many episodes have been lost to the sands of time, a healthy portion remain available to stream online, and revisiting this curious chapter of horror has become my favorite Halloween ritual. There’s a hokey appeal to the conspicuous old-fashioned-ness of the crackly broadcasts, all corn-syrup blood and rubber bats. Brown pushed the horror envelope by taking advantage of radio’s inability to graphically represent grisly material, allowing the suggestion of depravity and letting the listener’s mind fill in the rest.

Inner Sanctum Mystery host Raymond Edward Johnson poses with a presumably creaky door. CBS via Getty Images

Moreover, Sanctum hails from a time when consumers had a more formal relationship with what they listen to. In a pre-TV America, the radio was appointment entertainment, commanding rooms where sitting families would place the sum total of their attention on a narrative that leaves you behind if you zone out. There’s something meditative about doing nothing but sitting and focusing, eyes closed, imagination firing on all cylinders; it raises the zen state of lower wakefulness achieved by moviegoers to the Nth degree. While you listen, everything else stops.

As the popularity of long-form radio storytelling has declined, podcasts have moved in to fill the vacuum, but some of the jerry-rigged charm has been lost along the way. Freed from dependence on a gatekeeping broadcast station, independent outfits everywhere have flooded the internet with anthologies and long-form series updating Sanctum’s template. The White Vault is one such program, following a perilous expedition to a research facility tucked away in a frost-choked wasteland. Producer Travis Vengroff and creator/host Kaitlin Statz agree that the content and the platform housing it have both changed since Brown’s day.

“Older radio teleplays generally emphasized stage acting and live audio design,” they explained via email. “As many of the shows were performed live for radio, they created soundscapes on the fly using whatever objects or tools they could fit in a soundstage… From a production perspective, audiences now expect more.”

Attaining a standard of professionalism is more doable than ever, but that polish has widely supplanted techniques with their own time and place. As Vengroff and Statz put it, “Stories are now pre-recorded, edited, and mastered prior to being released. So instead of shaking heavy paper, actual sounds of thunder might be used, and the sounds of wind and rain might be used in place of a dramatic organ performance.”

That technological evolution is reflective of a wider shift away from the stylized pre-packaged irony embodied by Inner Sanctum Mystery and towards an approximation of real life. “Over-the-top acting was also desirable because shows during that era emphasized excitement,” the White Vault team said, “often taking listeners to distant locales to tell grandiose stories. While a podcasting sub-genre still exists to cater to the fans of the old radio plays, modern audio drama has since shifted its style.”

While the audio drama medium’s evolution clearly points forward, employing more sophisticated equipment and techniques, the limitations of Sanctum’s era forced personal touches that are now easily automated. Statz and Vengroff aren’t bothered by these sea changes, or by the notion that consumers might be taking in their handiwork while cooking, driving, cleaning, working out, or “powering through any mind-numbing tasks.” The listener has claimed dominion over the shape of their entertainment, pausing and playing as they please, streaming and downloading at their own pace.

Maybe it’s time to let the old ways die, and accept that Inner Sanctum Mystery’s specific register of mannered, corn-adjacent horror lives on solely as a novelty in a modern radio landscape. But what is Halloween if not the season of novelty, an occasion for goofy artifice, for plastic and foam?

Inner Sanctum Mysteries host Raymond Edward Johnson and actress Virginia Owen demonstrate the old head-in-a-hatbox gag. CBS via Getty Images

Excluding only sci-fi, horror attracts more purists than any single genre, and that diehard fanbase can be a double-edged sword. Slasher flicks remain the one trend-impervious box-office bet, as recently proven by the umpteenth Halloween’s resounding success, yet this comes at the cost of some measure of homogenization.

Plenty of people equate horror with straight-faced scares, as if its inherent value can be measured in ounces of cold sweat. Those in search of something a bit kookier can perhaps have a detached chuckle at kiddie-demo Halloween specials, but otherwise, they’ve got to search a little harder.

The Inner Sanctum Mystery, then, serves as an alternative to all things sleek and serious, occupying a universe where the words “gritty reboot” have yet to be uttered. This facsimile of time travel transports listeners to a horror paradigm governed by the notion that being scared should be kind of fun and kind of silly.

Brown preferred to emulate the feel of a fairgrounds haunted house rather than a house actually haunted, with the added benefit that most of his tricks had yet to calcify into cliché. Conceived with a wink and performed with absolute conviction, his work aptly embodies the spirit of Halloween as a jovial celebration of all things frightful. Every day was October 31 in the Sanctum, all the nights stormy, all the screams shrill, all the doors creaky.

Episodes of The Inner Sanctum Mystery are available to stream via archive.org,

Original Source -> Why the vintage terrors of The Inner Sanctum Mystery make for great modern Halloween fare

via The Conservative Brief

0 notes

Text

Design:

It was really interesting how they made Blair witch project posters, designing them like missing posters, as if the people really were lost. Using simple colours, just black and white or red and black, gives a strong contrast and memorable design. The faces of the characters and, most especially, the trees reflected the main feature of the film and its striking background, giving an eerie feel and providing some idea in advance of the kind of film this is to be: mysterious, threatening. The stark trees in an unwelcoming mist seem to take on a foreboding significance, as if they are the story, the primary player in which the vaguely outlined figures are to be the victims.

This poster is a marked contrast to the more common cartoon designs which arrange the characters so as to draw the eye to them, their facial features explaining much of the story’s supposed charm through their grimace of wry amusement or helpless mirth. Here it is typically simple, bright colours that express optimism; two character poses (sometimes with others in the cast arranged behind) introduce us to the cast that is to entertain us, so that we go to the film with an expectation of a joyous feeling, or of the laughter that is to come.

The Zootopia poster is designed, not only to give a representation of the film it publicises, but actually to look good as a thing in itself – though arguably all posters do this to some extent. The artists use the golden ratio method, giving a satisfying balance and proportion as you move your eyes around the poster, seeing the characters and the narrative clues behind them. The golden ratio determines how characters are positioned, their scale and proportion to the whole. In this there is mathematical principle: “Without mathematics there is no art,” said Luca Pacioli, a contemporary of Da Vinci (link).

With the colour used in the Zootopia, it’s very bright and catches your eye instantly, drawing your eye in to look at the bright and animated characters in the poster, choosing desiring colours which compliments all the colours which has been chosen on the poster. Especially towards children as they’re drawn to brightly coloured and animated things, as it’s designed towards the age range of young child, bringing out the simple glimpse of the film which is fun and entertaining, which the vide of the poster is.

Along with the wide diverse cast, showing different shapes and sizes, it really gives a good spell of normal in the film, giving the average feel of feel and giving a reality of live in the film. Showing kids that everyone comes in shapes and sizes. The method of showing reality within the film shows that the animators designed all the characters fully, along with giving each character a joyous feel.

Animation:

Animation is traditionally split into three styles: hand drawn (also known as traditional), Computer Generated (CG) and stop-motion. Whilst some can overlap, such as CG with 2D, drawing on the computer and adding effects with the CG can make a moving picture look 3D. Stop-motion and GC are rarely used together as this is labour intensive; however a good recent example of all three being used together is the John Lewis Advert of 2013, ‘The Bear and the Hare.’ The making of this film and the execution of the techniques can be seen on (Link)

Animation, normally used to entertain, can be used to bring awareness of more serious issues. Good work was done for The World Health Organization, to make the animation of the The Black Dog, a film which explains depression and encourages and empowers people to take control of their lives. The idea of calling depression a ‘Black Dog’ may well come from Winston Churchill, who suffered from depression, but here the image is used as the basis of some imaginative metaphors for various depressive states, the pictures conveying much more information than words, because they allow the reader to attach their own story to them.

Traditionally animation has been seen as something playful, and thus it features heavily in children’s entertainment – Disney being the prime example, but also Marvel comics (USA) and the Manga material coming from Japan. However, with a generation growing up who accessed much of their expanding awareness of the world through it, animation has now featured in adult themes, from graphic representation of WW1 in the French trenches to Italian pornography.

Yet this older generation who is used to traditional hand drawn animation from the use of, resent the newer generation such as computer animation, as they think it lacks character and is easy, since the computer does the work. This is not entirely fair, as it can take as much time as the hand drawn, sometimes even more, as they still have to design and shape the characters on the computer; sometimes software itself has to be made for the kind of animation they want, as some animation softwares have not yet caught up with the style they want to use.

Animation often involves collaborating with music; this might be to make a music video using animation, like Pink Floyd’s ‘The Wall’. It might be the reverse, where music compliments the film, adding to its mood. Damian Albarn’s work with the Gorillaz even used cartoons as the only reprentation of the band’s music.

A quantum leap in animation was the discovery of ways to combine human acting with animation to shape movement. Here the idea is to place sensors at strategic points on the actor’s face and body, so that as well as voice-syncing they can body sync, what is called ‘Motion capture’. The Polar Express was one of the first examples, and used Tom Hanks as the train guard. The effect is to get a realistic combination of face, body and voice to animate a character.

Portraits

Portraiture is one of the oldest of arts, and a feature of civilisation, as its purpose is often to reflect a person’s value within a given hierarchy. We have portraits of Egyptian kings from 5,000 years ago, showing their wealth and significance as rulers. The actual features would have made them recognisable at the time, but was not the purpose of the portrait, which was purely representational of power. For example, an emperor’s image on a coin had to look something like him, but was not designed to be studied. Portraits as a likeness came later. Their primary purpose was to show the power, importance, virtue, beauty, wealth, taste, learning or other qualities of the sitter. (http://www.tate.org.uk/learn/online-resources/glossary/p/portrait)

Painting to achieve a good likeness was something that became valued in the Renaissance when the artist’s skill was marketable amid the growing interest in all things cultural. An apprenticeship to a great artist was seen as an excellent prospect for a young painter with talent. Here it began to matter exactly what the subject looked like, although still it was mainly kings and queens who were painted. Only later, as people began to enjoy the skill of the artist in capturing a personality in paint, did the subject matter begin to extend to faces of ordinary, even poor people, whose face happened to be interesting, perhaps because it told the story of a life. This reflected the growth of the middle classes, and the presence of money in trade which raised ordinary merchants to positions of significance. It also saw portraiture become valuable as a thing in itself. Rembrandt’s portraits for example, are valuable for their beauty, and the person of the sitter has no importance at all. By this time art had a value as a commodity.

Even so, before the era of photography (and even after it) wealthy people still wanted to have their portrait painted by someone with a good reputation, like John Singer Sergeant. It was in any case a while before cameras could give a good likeness, capturing perhaps a fleeting expression of humour. The earliest cameras, needing long exposure times, made the subject look wooden and staring.

After cameras gave reasonable colour portraits in the post-war years, a good oil portrait was valued as something for the elite, as it showed someone could afford to pay for it. Whilst a camera portrait from a studio gave a good representation, a portrait in oils had a sense of something that an artist saw that went beyond mere representation. Portraits began to move away from representing what people looked like to capturing their essence. Lucien Freud’s portrait of the Queen gave offence because he made her look ugly in his attempt to show who he felt she really is. Graham Sutherland’s portrait of Churchill was destroyed by Churchill’s wife.

Caricatures are another form of portrait, and are popular with street artists in tourist locations. Sadly there is now software available to create a caricature from a photograph, but the caricaturist’s art remains a popular one, not least as it seeks to emphasise personality as well as capture a likeness.

0 notes