#i even made a shader for the guitar strings to show how they're woven out of smaller threads which nobody is gonna see at this res ^^'

Text

Music theory (for science bitches) INTERLUDE A - what's with a guitar?

Got to play guitar for the first time in me life last night! Answered a lot of questions about one of the world's most common instruments, some I knew I had, some I didn't.

So here's what I picked up.

Tuning

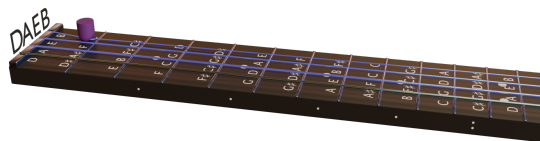

The guitar I tried playing was an electric guitar with four strings that had been modified to be tuned in fifths, which apparently makes it similar to a tenor guitar - a familiar tuning for me since the violin and erhu are also tuned in fifths. But guitars are usually tuned in fourths.

'Tenor' here isn't really referring to a specific range the way it does in regards to singers - it seems kinda like more of an adjective meaning 'higher than usual and tuned in fifths'. So you can have the strange-sounding 'tenor bass' guitar. Although with the more obscure guitar variants, the language seems to be kind of a free-for-all.

Tenor guitars are usually shorter than regular guitars, and with different strings, but ultimately as long as you don't break the strings, you can tune to whatever frequencies by adjusting the tension. The standard guitar tunings are ultimately a matter of convention.

Besides that, the major design differences between a guitar and a violin type instrument are... the strings are arranged flat rather than in an arc, and they have frets.

The flat arrangement makes it much easier to play chords. You can simply move your fingers, or plectrum, in a straightish line and hit multiple strings.

Frets are metal rods which protrude from the fingerboard, and they make it much easier to hit particular pitches. You press the string behind the fret (further from the bridge/soundbox), and this holds the string against the fret, reducing the vibrating segment to an exact length. So there's no need to train your muscle memory and ear to recognise whether your fingering is in tune, as is the case on violin, erhu and the like. But it does make pitch-varying techniques like vibrato require a different approach. More on that in a bit.

The frets are positioned in semitones. There are some little dot markings that indicate the major third, the fourth, the fifth, the major sixth and a double dot for the octave, which helps with navigation.

Due to the way guitar strings are tuned, the way you construct chords is a little counterintuitive. Let's take for example a standard minor triad chord.

On a piano, you play the base note, a note three semitones up from that (the minor third), and a note seven semitones up from the base (the fifth). This will generally result in your fingers being fairly evenly spaced, e.g. A minor looks like...

On a guitar it's a bit more complicated. Intuitively, you might expect to play the three notes in this chord in order, on strings of increasing pitch, but if you try this you would conclude realise that the gap between strings is larger than a major third.

So, the strings I had were tuned DAEB (similar to a violin, but without the G on the bottom, instead gaining a B on top). If you want to play A minor you need to play A, C and E. The A and E can be played on open strings, but what about that C? It lies in between those two strings.

So, I thought, what if I played the C on the D string underneath the A? In that case, you'd put your finger on the 11th fret of the D string and strum the D, A and E strings. That would hit the same notes you would hit on a piano, just arranged differently on the instrument...

However, that is not how guitar players normally form chords. The reason is that, while this may work for open strings well enough, if you wanted to play a minor triad further up, it doesn't really work at all: there's no physical way your hand can be up at the top of the guitar on some strings and all the way down at that C for others.

Instead, guitar players take advantage of the convention of octave equivalency and play the next C up. This can be reached on the B string very easily, so for this A minor chord, you can play it on A, E and B:

On a piano, this chord would look like this:

This would be a goofy thing to do on a piano, but it makes things much easier on guitar.

In terms of the resulting sound, this will shift the fundamental of the C up an octave, and remove a certain proportion of the overtones - more on that in the upcoming next part of the music theory notes (for science bitches) series. So it will affect the timbre of the sound. However, it will still generally sound like A minor.

That's all well and good if you've got open strings in your chord, but what if you want to play, say, B minor? Well, you can use one of your fingers in a technique called a 'bar', which simply means you hold your whole finger against the fingerboard to press all the strings at a particular fret...

This essentially lets you calculate the chords in the same way as you would at the open strings, so you can just memorise the general shape of minor chords and slide it around.

My friend came up with a few little chord progressions for me to play. For communicating them she would say like 'ok then play 2 2 0 0' with the numerals communicating which fret/semitone to play - I believe this is similar to the notation used in tablature. (In this case that would amount to E B E B, a doubled-up 'power chord'). She figured out the progression pretty intuitively - when we worked out the names it turned out to include a variety of suspended or diminished chords or one chord over another, and other such things. (She had a phone app that would let you put in the positions and would tell you a name).

One of the cool features of a physical instrument is that you can just try shit. It was very informative to see how chord progressions come together and how the different voices seem to relate to each other.

The mechanics of playing the thing

The other major difference with guitar is like... damn those things are long!

Although the body of an electric guitar does not have to act as a soundbox, the shape of the guitar still turns out to be way more constrained and thought-out than I realised. There are all sorts of cutaways designed to help the guitar balance comfortably on your leg, sit comfortably against your abdomen, and so on. The 'horns' of the guitar aren't just decorative: they allow you to slide your hand further down the neck.

I got to see an ultra-light 'headless' guitar where the tuning pegs are at the bottom end, which saves weight. There are all sorts of little nuances about where the cable goes and so on.

The most awkward part was really the hand that goes on the neck and plays the chords. The frets help but they don't go that far.

Honestly, making chords on a guitar... my fingers are apparently pretty long, but it still felt like I'm contorting my hand, like I could feel the tension so much stretching across even a few frets. By the same token, pressing the strings was ouchy. It was the same on the zhonghu when I started though, so I'm sure if I kept at it I'd get the callouses I'd need to not feel painful anymore.

It can be quite important where you place your fingers between frets. Too far from the fret, and you don't create a good contact, so the string doesn't sound properly. Too close to the fret, like if you're right on top of it, can also be problematic. You have to apply enough pressure to hold the string firmly against the fret. All of this impressed on me how fiddly it is to play one of these things, let alone do it in a showy ostentatious way like guitarists do.

Strumming was also a bit fiddly. Unexpectedly, the biggest problem I tended to have was strumming too hard. With all the amplification involved, it seems you want a really light touch, just brushing the plectrum (or fingers) against the strings.

It turns out there's some complexity to strumming and plucking. My first instinct was to just go up down, up down, but it seems like actually the best approach is to alter the direction for different musical phrases, so sometimes you want to go two 'ups' in a row or two 'downs' in a row with something like a 'null stroke' in between to get your hand in position. This apparently just comes intuitively to an experienced guitarist, just like bowing does to an experienced violinist or erhu player, but maintaining the pattern definitely added to the cognitive load of the instrument at my level.

The guitar I was playing had a "synchronised tremolo bridge", similar to the one in the picture, meaning it was on a kind of levered spring anchored only at one end. Unlike a violin or erhu, the bridge of a guitar is very very close to where the strings are anchored, and adjustable per-string. The lever you see on some guitars is used to tilt the bridge while the strings are sounding, creating a vibrato (oscillation of pitch) effect. (I don't know why it's called a tremolo bridge rather than a vibrato bridge. In classical music 'tremolo' refers to either playing a bunch of the same note really fast, or oscillating volume. But this bridge definitely primarily affects pitch.)

(Incidentally, some guitars have non-parallel bridges and frets designed to give the lower strings more distance to play with which affects the relationship between string weight, tension, and pitch - it's a whole thing apparently.)

You can also create a vibrato effect by wiggling the string sideways against the fingerboard to adjust the tension in it.

The electric part

The big difference between an electric guitar and an acoustic guitar is that the vibrations in the strings are used not for the sound they make directly, but as an input into a signal chain.

I had wondered for a long time how guitar pickups work. It turns out they work by magnetic induction; the string is made of ferromagnetic material and the pickups have little magnets in them which induce a magnetic field in the string, and the vibrations of this magnetic field are picked up by an electromagnet inside the guitar. This has the interesting implication that an electric guitar does not require a medium to generate a sound, so it would work just fine in space (though of course the amplifier must be in air to transmit sound).

There are multiple sets of pickups at different points along the string, which means they get different sets of overtones depending on the amplitude of the different standing waves near that pickup; there is a little liver on the face of the guitar which allows you to adjust which pickup is active. Selecting the pickup closer to the bridge is effectively a kind of mechanical high pass filter on the strings.

The weak alternating current created by the vibrating strings is then passed along a shielded coaxial cable to an amplifier. This creates an opportunity to mess around with that signal - to add reverb, equalisation, etc. or more purely electric effects like 'phasing' and 'flanging'.

The 'distortion' effect so widely used in rock and related genres comes from multiplying the signal pre-amplification to the point that it saturates the amplifier, resulting in an effect similar to digital clipping. Traditionally this was done by literally boosting the signal louder than the amp's tolerances (referred to as 'gain' by guitarists), but nowadays they've found ways to get an equivalent effect that are less likely to break the equipment. (Honestly, I liked the 'cleaner' sound of when the guitar was not clipping a lot more than the heavily distorted version, but it's worth noting here as one of the most well known guitar effects)

These effects are typically implemented using 'pedals' which are just a small circuit that applies a particular toggleable signal modification, making the whole chain of guitar - pedals - amplifier collectively act as something like a modular synthesiser. The guitar acts as a signal generator, the pedals and amp process it, and finally it's played out of a speaker.

This is not unique to guitars, the same principles would basically apply to any 'electric' instrument, but for whatever historical reason guitars were the instrument that became 'electric' first, and they're still by far the most common.

It was interesting to me how technical the whole setup is. The amp has all sorts of dials to apply built-in effects and adjust its tone response in various ways; the guitar also had a few.

Analogue instruments give fairly limited options to control timbre. So like, on the erhu for example - you have a huge amount of pitch control, you can do a lot to adjust dynamics with the way you move your bow, but for timbre there's only a handful of dimensions in the 'parameter space' and like, ultimately I'm finding my way to a 'best way to do it' where it 'sounds like an erhu is supposed to sound'.

Electric instruments on the other hand has a huge multidimensional space of timbre possibilities, so if you understand guitars, you can stand on an amp for a while zeroing in on the exact sound you want while the infatuated canmom sitting next to you gets increasingly hot under the collar. For understanding what's going on in guitar music, it's evident classical theory can only get you so far.

So...

...am I gonna start learning guitar too now? As much as I admire my friend's ability to play dozens of different instruments... not in any sort of serious way, erhu/zhonghu is gonna be my main instrument for a good while (and I physically could not take a guitar home with me anyway with all the shit I'm carrying). But it's very interesting to see other parts of the string instrument space, and definitely gives me a better appreciation for all the things guitarists are doing.

Music's cool, I regret that I stopped playing... but now's definitely a good time to get back into it!!

#music#canmom vs music#music notes#music theory notes#spent rather too long making 3d models for this instead of doing work lol#i even made a shader for the guitar strings to show how they're woven out of smaller threads which nobody is gonna see at this res ^^'#guitars

22 notes

·

View notes