#it's about the cyclical tragedy and characters both doomed by the narrative and haunting the narrative

Text

it's all "must a book have a plot? is it not enough to just write about vibes?" until nathaniel hawthorne writes a 300+ page novel based entirely on haunted house vibes. then it's suddenly "too long winded" and "nothing happens" and he "took 300 pages to say something that could have been said in 40"

#/hj#is this the best novel i've ever read? absolutely not oh my god he goes on and on about philosophy and his paragraphs are SO LONG#but listen. it's about the vibes. it's about the haunted house. it's about the generational curse and is it actually a curse? who knows!#it's about the mystery of whether or not something supernatural is happening or if everything has an explanation#it's about the cyclical tragedy and characters both doomed by the narrative and haunting the narrative#it's about how dwelling forever on what could have been will prevent you from moving forward#it's about how you shouldn't judge someone based on appearance#it's about how the end of your life is only the beginning of your legacy and YOU get to decide if you will be simply repeating the actions#of your ancestors. or if you are going to be the one who finally breaks the chain and says NO. this is wrong and i won't stand for it#it's about choosing which family you hold onto and which family you distance yourself from#it's about the fact that alice deserved better and hepzibah's loyalty deserves recognition and phoebe might give everyone sunshine#but she should learn to keep some of it for herself too#it's about the fact that hawthorne takes 300 pages to say:#our property and every physical thing we have in this life will not follow us and we should not live our lives according to the whims dead#men left in their wake. but it does no one any good if we erase the past entirely#you just have to be willing to see it#SORRY APPARENTLY I HAVE. A LOT OF FEELINGS ABOUT THIS BOOK LOL#hello grace here

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

What the Candyman Ending Means for a Sequel and His Immortal Legend

https://ift.tt/3gNNBgZ

This article contains Candyman spoilers.

It is an exquisite final image. Swarmed in a symphony of bees and standing triumphant over his latest victim—a police officer sprawled out in an alleyway’s gutter—Candyman looks joyful. He’s the monster who’s haunted the ruins of what was once Cabrini-Green for more than a hundred years, and the legend who frightened children and caused lovers to cling closer in their rapture, and now he’s at last returned to his flock. Only this time Candyman is saving the woman who summoned him instead of destroying her.

As Teyonah Parris’ Brianna Cartwright looks on, her salvation is a wondrous thing—both a ghost and a living ghost story—who has killed something far scarier than his legend. The truth of this is told by the bodies of corrupt police officers strewn around the scene. Moments earlier, those same cops in cold blood killed Brianna’s boyfriend, artist Anthony McCoy (Yahya Abdul-Mateen II), after assuming from a glance this Black man was the criminal they sought. In doing so, they permanently secured Anthony’s place in the Candyman mythos, crafting his sad story onto the enduring larger one written in blood by the Black bodies that’ve been destroyed on these lands for more than a century. So when Brianna summons Anthony back by saying “Candyman” five times, it is not Abdul-Mateen’s face we see. Rather a de-aged Tony Todd stands defiant again. The everlasting saga of the Candyman walks again among us.

It’s a loaded image that speaks greatly about the movie we’ve just watched… and the inevitable Candyman sequel we are about to get.

Because rest assured, there will be a Candyman 2 (or Candyman 5, if we’re getting technical). After all, this new movie just grossed an impressive $22.4 million in its opening weekend, which nearly matches the film’s entire $25 million budget. There is thus little doubt about whether Universal Pictures will want to continue the story. But of course the entire point of Candyman is that this is a story which never ends, not in the last vestiges of Cabrini-Green, and not in America. All of which makes the prospects of another movie fascinating…

A New Candyman for a New Type of Victim

If Bernard Rose’s original Candyman (1992) was a Gothic Romance of the nihilistic order—complete with the loaded imagery of a Black man haunting the dreams of a white woman—then Candyman circa 2021 is functionally something else. At its barest bones, it’s a werewolf movie, and a Jekyll and Hyde reimagining. Abdul-Mateen’s Anthony is a good man who says his prayers by night (or at least kisses Brianna before bed), but when the moon rises, and “Candyman” is whispered five times before a mirror, something supernatural and beyond his control takes hold.

If Virginia Madsen’s Helen was bedeviled by the assumption that she was responsible for Candyman’s murders in the original movie, Anthony is damned by the much worse realization that he is becoming Candyman. Of course the idea of what that means is something far more tangible than urban legends about mirrors and spirits.

As eventually explained by Colman Domingo’s William Burke, Candyman is more than just a ghost story; it’s the tale of systemic oppression of Black men since time immemorial. The original Candyman might’ve been Daniel Robitaille, a Black artist in 1890s Chicago who dared to fall in love with and impregnate a white woman—which led to his body being mutilated by a lynch mob—but as Burke explains in Candyman, all those innocent Black men who’ve been brutally murdered by white authority over the decades were real men who existed beyond the confines of campfire stories. They lived, they loved, and they died horrible, gruesome deaths. In the case of Burke’s own childhood boogeyman, Sherman Fields (Michael Hargrove), that came in the form of a simple neighborhood man who liked giving candy to children, and the cops naturally assumed he was responsible for the recent death of a white child before shooting him.

These real stories are twisted into an urban legend that shrouds the ugliness under a veneer of Gothic horror and romance. That is the true tragedy of Candyman. Hence the horror of Anthony becoming just another Black face to fear for those with the power, another boogeyman whom cops will eventually shoot on sight simply for being in the wrong place at the wrong time. Society is literally forcing and contorting these Black men’s bodies to fit a prejudiced assumption.

That is why, according to Burke, and by extension Nia DaCosta and Jordan Peele’s script, the Candyman story lives on with a mystical sort of power. Throughout the movie, Anthony McCoy is haunted by Candyman’s reflection in the mirror, even though we rarely get a good look at him. The role of a monster is being thrust upon him.

Yet who does the revived Candyman kill? Whereas in the original film he considered the impoverished residents of Cabrini-Green’s projects his “children” and “flock,” whom he occasionally would select victims from to keep his legend alive, the Candyman of 2021 has few Black faces to cull from. Gentrification has literally pushed them out, and the high-rises Rose and Tony Todd shot the original Candyman in have been torn down and erased.

So Candyman’s victims in the 21st century are largely the white faces who’ve displaced the original flock. Tellingly, the first victim in the new movie is Clive Privler (Brian King), a white man who curates Black art and generates wealth for himself by exploiting local trauma. What sets Anthony on his fateful descent is being told by Clive that art about Black struggle in the South Side is played out; dig into that Candyman nonsense in Cabrini-Green instead. So it is that Clive and his girlfriend, who pay no credence to the rituals and awe Cabrini’s previous residents had for Candyman, are among the first to summon the ghost—tasting his glorious treats.

The next victim is a white art critic who has little interest in Anthony’s art when she first sees it. Rather she has the chutzpah to tell a Black man about why he is guilty of gentrification and dismiss his art as blunt and common. Yet when she sees commercial appeal in the story following Clive’s gruesome murder—suspecting there is now a Black story to benefit from telling herself—she circles back to Anthony’s Candyman art and seals her fate.

In the original Candyman, Tony Todd purrs, “They will say that I have shed innocent blood. What’s blood for, if not for shedding?” In 2021, no one who dies by Candyman’s hook is particularly innocent. Even the teenagers who summon him to a high school bathroom have benefitted from a culture that relies on complicity. They were of course too young to know they’re part of that system… but then so was Anthony when he was taken as a baby by the Candyman 30 years ago, and doomed to the same cyclical violence perpetrated against Black men each generation. Innocence and ignorance save none in this story we’ve built for ourselves.

Which brings us back to that ending with Anthony dying so as to fully resurrect Candyman’s legend. As Burke plainly spells out, a ghost story for Black communities could be laughed off by the elite and bourgeois white classes in the past. Now Candyman can live forever if the blood he is spilling belongs to white culture—beginning with the cops summoned to the scene.

Where Does This Leave the Candyman Sequel?

The last line of the new Candyman is Tony Todd’s visage commanding Brianna to “tell everyone.” He’s back. The full impact of that is revealed during Candyman’s end credits. Initially, the film fades out on DaCosta’s use of haunting paper shadow puppets, which were used throughout the movie to recreate old myths about Candyman: Helen Lyle’s fate and Daniel Robitaille’s courtship of a wealthy white daughter and a father’s terrible vengeance. Yet if you stay long enough in the theater, a new shadow play is enacted, one in which an artist loses his mind, and his paint brush is replaced by a hook.

This puppet play ends like the movie: Candyman has risen and five treacherous police officers are left in pieces. The implication is, clearly, that Brianna has obeyed Candyman’s edict and spread the good word.

Yet if this is the new legend, where can that lead a potential follow-up? Is Candyman essentially a superhero movie? The story of a ghost who punishes those white faces that dare dismiss the Black culture they’ve supplanted and profited from?

Possibly, although I think that is too reductive and simplistic for DaCosta and Peele, as well as somewhat of a betrayal of Candyman’s appeal if it stops there. Like the beautifully haunting melody of Phillip Glass’ original Candyman musical theme, there is an intoxicating allure found in the sorrow and tragedy wrought by this character. If Candyman’s story is transitioning from one about meta-textual mythmaking to one about cultural revenge against repression, then it must still remain a revenger’s tragedy.

Read more

Movies

What to Expect from the Candyman Reimagining

By David Crow

Movies

Candyman Origins Explored in Haunting Video from Nia DaCosta

By David Crow

As Burke said in the new movie, Candyman is a tale folks use to comprehend and organize their thoughts around long systemic violence against Black people in this community, beginning with Daniel and carried on through Anthony in this particular case. That story is, sadly, unending in American life, but it can be told in a new way by a Candyman sequel.

If the 2021 movie is, in its barebones, a werewolf narrative with a central victim coming to terms with his transformation, then a follow-up could pivot to returning to the heightened operatic quality of the original Gothic film. For instance, as brutal and merciless as DaCosta’s on screen violence is in the new picture, I would argue there is nothing as unnerving or unforgettable as Tony Todd’s big entrance in 1992.

Halfway through the original movie, after being told repeatedly there is no such thing as Candyman, Helen and the audience eventually turn the corner in a parking deck and there he is: formally draped in a fashionable coat and standing at a posture that is simultaneously inviting and foreboding. He’s no slasher killer who will float across the floor to get you. He is an almost godlike presence who has the infinite patience of a spirit that knows time is on his side, and his reach is inescapable. The more Helen attempts to resist, the more she and the audience are helplessly drawn in by the irrepressible power derived from a legend.

A sequel to Candyman (2021) could lean into those abilities and allow Abdul-Mateen to fully inhabit the role in the way Todd did for a previous generation. Abdul-Mateen certainly has the talent to use a soft-spoken voice to dominate the screen. However, the trick could be to use it to a different end.

With Candyman returned as a spirit of revenge against a white society that has finally grown forgetful enough to move into his domain—the ruins of Cabrini-Green—he can now be a presence that at last victimizes those who oppressed Daniel Robitaille, Anthony McCoy, and all the others. By virtue of that long sad history, the melancholic fatalism of the character can never feel empowering… but it can be righteous.

Anthony becoming the face of Candyman for this new era makes sense as the story of the artist’s madness and demise is now forever coupled to the legend. Just as Anthony saw Sherman Fields in the mirror because William Burke told him the Candyman story of his youth, so will new generations see Anthony McCoy when they dare summon Candyman.

And if Anthony is the face of Candyman going forward, he can continue to haunt Brianna’s dreams while drawing her into providing him more victims—sweets for the sweet—which would recontextualize the fatalist romance from the original movie. Theirs could be the ultimate art piece in the new Candyman’s mind, one where he cuts a bloody canvas so vast that even Lakeshore Drive cannot look away. How delicious.

cnx.cmd.push(function() { cnx({ playerId: "106e33c0-3911-473c-b599-b1426db57530", }).render("0270c398a82f44f49c23c16122516796"); });

The post What the Candyman Ending Means for a Sequel and His Immortal Legend appeared first on Den of Geek.

from Den of Geek https://ift.tt/38nbpDM

0 notes

Text

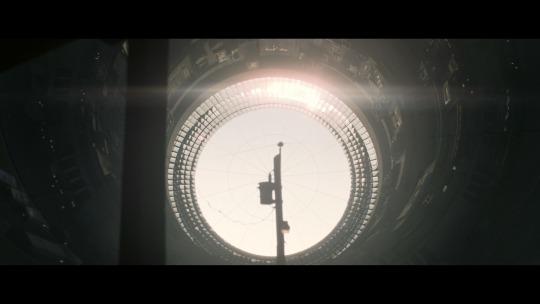

Interstellar and the Visual Metaphor

As has been well established, Christopher Nolan is a master of cinema storytelling and narrative development through visual and thematic elements, and this shines through brighter than ever in his seminal sci-fi work, Interstellar. One of the most prevalent visual metaphors/recurring motifs is the circular nature of time as represented through both circles and repetition of lines, footage, and scene composition. As would make sense, one cannot quite fully begin to comprehend just how Nolan works in elements of parallelism and recurrence throughout the movie until after the film has almost reached his conclusion, and this is when all of the mental jigsaw pieces begin to fall into place. If one pays careful attention, many lines that are delivered in the exposition of the film work their way back around and are delivered once again at the film’s denouement (for example Cooper and Murph’s use of the phrase “you are/were my ghost”). In addition to this, when the audience is shown one of the first wide landscape shots of Cooper Station what appears on the screen in the foreground is a television set which is playing a video clip of an elderly woman being interviewed and speaking about the state of the earth as it was presented at the beginning of the film, a video clip which was itself shown at the very beginning of the movie. In the background of this shot one sees Cooper Station stretching off into the distance, forming a huge circle which Nolan uses in this instance as a rather blatant visual metaphor for the cyclical nature of time as presented in the film and hammered home by the presence of the interview clip that was shown at the very beginning. This trick of having Cooper Station stretch away in the background is used once again a short while later in which the circle forms a sort of halo around Cooper as he relaxes on the front porch of his replica house and sips a beer. In this case the circle is there once again to prime the audience to be looking for these representations of recurrence, and one doesn’t have to look very far to find it: the fact that Cooper is literally placed in the exact same position that he was at the beginning of the film, sitting on his porch, the camera positioned in the exact same position represents physically the fact that his story has come full circle. This scene actually features a voiceover from Cooper in which he states that he is tired of feeling like he is always ending up right where he started, explicitly highlighting to the audience the prevalence of the idea of a cyclical or nonlinear time, and leading the audience member to start noticing many of these seemingly insignificant details that together contribute to a beautiful form of artistic thematic expression. That said, Cooper finishes this voiceover line by saying that he wants to know where we’re going, reflecting his established personality trait of never wanting to accept the way things are, always striving to find new, better ways of doing things or improving himself, and his belief that a stagnant humanity is self-crippled and doomed (as is shown in his conversations with his father-in-law, the decisions he makes while on the Endurance, his finally leaving the station to go find Brand, etc.).

One of the most beautiful, impactful, and touching elements of Nolan’s film is the idea of the “ghost��. Nolan plays around with both the literal and figurative uses of the word, utilizing it as a sort of pun throughout the movie, though not for humorous effect but to accentuate the highly personal father-daughter narrative, internal character conflicts, the nature of the relationship between parents and children, and to seamlessly weave elements of the science fiction into the human fiction. Nolan takes the idea of a ghost in a direction different from the traditional view, a direction which is described most directly by Murph later in the movie when she states that she was never afraid of the ghost, but referred to this entity as such because it felt like a person to her. One interpretation of what a ghost is is literally the spirit of residual soul of a deceased person, but one can also be haunted by a figurative “ghost” if some idea or memory lingers in the mind of an individual, one that is not easily lost. However in Interstellar, Nolan uses the idea of a ghost in the sense that it can be a memory, one that accompanies you wherever you go and remains with you after the physical presence has left you, specifically the memory of a parent. Cooper early on in the movie, when he is trying to make things right with Murph before he leaves, he says that his wife told him after the birth of their children that their purpose from thereon out is “to be the ghost of our children’s future”, but Cooper says that in that moment he needs to be alive, to not be a ghost. In leaving, however, he is in reality doing the exact opposite of what his words say, creating an interesting verbal irony in which by leaving and not returning he lives on for Murph only in the form of a memory: a “ghost” to drive her life’s work and accompany her for the rest of her life. But, at the same time, the viewer eventually discovers that Cooper goes on to literally become the physical “ghost” that communicates to Murph as a child, so he is in actuality becoming her ghost in both the literal and nonliteral sense, completely contradicting what he says to Murph in that scene. This situation, for me, is most reminiscent of a reversal (an element of many ancient Greek tragedies), in which all the actions of the hero of the story lead to the occurrence of exactly the opposite of what the hero desired (think Oedipus fulfilling his destiny through the very act of trying to avoid his fate). The beauty of this creative narrative nuance is only brought to full realization at the very end of the film in which Murph realizes that Cooper is her ghost, and the full emotional battering ram of the ramifications of this realization manifest when Cooper, holding his dying daughter’s hand, tells her that he was her ghost, a sentiment which is directly echoed by her statement that she always knew he would come back because her father made her a promise. In this way, Nolan captures the emotional energy of the completion/conclusion of the ghost motif/reversal and carries it onward throughout the whole rest of the scene, not losing an ounce of its electric personal impact.

1 note

·

View note