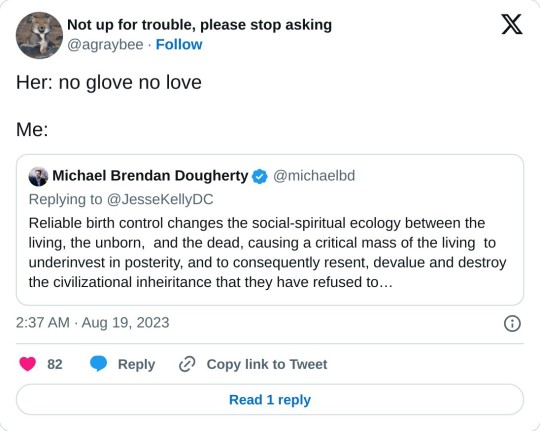

#and a social cultural and constitutional 'scholar' at the american enterprise institute

Text

#michael brendan dougherty is a senior writer for national review#and a social cultural and constitutional 'scholar' at the american enterprise institute#but however could you tell?!

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Imagining futures; escaping hell; controlling time; living in better worlds.

------------

What we see happening in Ferguson and other cities is not the creation of liveable spaces, but the creation of living hells. When a person is trapped in a cycle of debt, it also can affect their subjectivity and temporal orientation to the world by making it difficult for them to imagine and plan for the future. What psychic toll does this have on residents? How does it feel to be routinely degraded and exploited [...]? [M]unicipalities [...] make it impossible for residents to actually feel at home in the place where they live, walk, work, love, and chill. In this sense, policing is not about crime control or public safety, but about the regulation of people’s lives -- their movements and modes of being in the world.

[Source: Jackie Wang. Carceral Capitalism. 2018.]

------------

Pacific texts do not only destabilize inadequate presents. They also transfigure the past by participating in widespread strategies of contesting linear and teleological Western time, whether through Indigenous ontologies of cyclical temporality or postcolonial inhabitations of heterogenous time. [...] Pacific temporality [can be] a layering of oral and somatic memory in which both present injustices and a longue duree of pasts-cum-impossible futures still adhere. In doing so, [jetnil-Kijiner’s book] Iep Jaltok does not defer an apocalyptic future. Instead it asserts the possibility, indeed the past guarantee, of Pacific worlds in spite of Western temporal closures. [...] In the context of US settler colonialism, Jessica Hurley has noted “the ongoing power of a white-defined realism to distinguish possible from impossible actions” [...]. In other words, certain aspects of Indigenous life under settler colonialism fall under the purview of what colonizing powers define as the (im)possible. [...] Greg Fry, writing of Australian representations of the Pacific in the 1990s, notes that the Pacific was regarded as facing “an approaching ‘doomsday’ or ‘nightmare’ unless Pacific Islanders remake themselves”. From the center-periphery model [...], only a Malthusian “future nightmare [...]” for Pacific islands seemed possible. [...] Bikini Island, where the first of 67 US nuclear tests took place from 1946 to 1958, was chosen largely because of its remoteness [...]; nuclear, economic, and demographic priorities thus rendered islanders’ lives “ungrievable” [...]. The [...] sentiment was perhaps most famously demonstrated in H*nry Kissing*r’s dismissal of the Pacific: “There are only 90,000 people out there. Who gives a damn?” [...] Such narratives were supposed to proclaim and herald the end of Pacific futures. Instead [...] Pacific extinction narratives [written by Indigenous/Islander authors] conversely testify to something like the real resilience of islanders in the face of a largely deleterious history of Euro-American encounters. More radically, they suggest the impossibility of an impossible future. Apocalypse as precedent overturns the very world-ending convention of the genre. By turning extinction into antecedent, [...] [they aspire] toward an unknown future not tied to an apocalyptic ending.

[Source: Rebecca Oh. “Making Time: Pacific Futures in Kiribati’s Migration with Dignity, Kathy Jetnil-Kijiner’s Iep Jaltok, and Keri Hume’s Stonefish.” MFS Modern Fiction Studies. Winter 2020.]

------------

With the machinery finally installed on the property of the Manuelita estate, Don Santiago Eder launched the first industrial production of refined white sugar in Colombia on the “first day of the first month of the first year of the twentieth century.” Such deeds, mythologized and heroic in their retelling, earned Santiago Eder respect as “the founder” and his sons as “pioneers” in the industrialization of provincial Colombia. Their enterprise [...] remained the country’s largest sugar operation for much of the twentieth century. In 1967, [...] E.P. Thompson described the evolution and internalization of disciplined concepts of time as intimately tied to the rise of wage labor in industrializing England. His famous treatise on time serves as a reminder that the rise of industrial agriculture affected a reorganization of cultural and social conceptions of time. [...]. The global ascendancy of the Manuelita model of work contracts and monoculture in the second half of the twentieth century underscores the acceleration of the Plantationocene, but the historical presence and persistence of alternative [...] time should serve as a reminder that [...] futures and the demarcation of epochs are never as simple as a neatly organized calendar.

[Source: Timothy Lorek. “Keeping Time with Colombian Plantation Calendars.” Edge Effects. April 2020.]

------------

For several weeks after midsummer arrives along the lower Kuskokwim River, even as the days begin to shorten, the long, boreal light of dusk makes for a brief night. People travel by boat [...]. When I asked an elder about the proper way to act toward Chinook salmon, he instructed me: “Murikelluku.” The Yup’ik word murilke- means not only “to watch” but also “to be attentive” [...]. Nearly fifty years ago, Congress extinguished Alaska Native tribal autonomy over [...] fishing [...]. The indifference of dominant [US government land management agency] fisheries management models to social relations among salmon and Yupiaq peoples is evocative of a mode of care that Lisa Stevenson (2014) characterizes as “anonymous.” When life is managed at the level of the population, Stevenson writes, care is depersonalized. Care becomes “invested in a certain way of being in time,” standardized to the clock, and according to the temporal terms of the caregiver, rather than in time with the subject of care herself (ibid.: 134). Stevenson identifies care at the population level as anonymous because it focuses exclusively on survival – on metrics of life and death – rather than on the social relations that make the world inhabitable. Thus, it is not namelessness that marks “anonymous care” as such, but rather “a way of attending to the life and death of [others]” that strips life of the social bonds that imbue it with meaning […]. At the same time, conservation, carried out anonymously, ignores not only the temporality of Yupiaq peoples’ relations with fish, but also the human relations that human-fish relations make possible. Yupiat in Naknaq critique conservation measures for disregarding relations that ensure not only the continuity of salmon lives but also the duration of Yupiat lifeworlds (see Jackson 2013). Life is doubly negated. For Yupiaq peoples in southwest Alaska, fishing and its attendant practices are […] modes of sociality that foster temporally deep material and affective attachments to kin and to the Kuskokwim River that are constitutive of well-being [...]. As Yup’ik scholar Theresa Arevgaq John (2009) writes, cultivating relations both with ancestors and fish, among other more-than-human beings, is a critical part of young peoples’ […] development [...]. In other words, the futures that Yupiaq peoples imagine depend on not only a particular orientation to salmon in the present, but also an orientation to the past that salmon mediate.

[Source: William Voinot-Baron. “Inescapable Temporalities: Chinook Salmon and the Non-Sovereignty of Co-Management in Southwest Alaska.” July 2019.]

------------

[C]oncentration of global wealth and the "extension of hopeless poverties"; [...] the intensification of state repression and the growth of police states; the stratification of peoples [...]; and the production of surplus populations, such as the landless, the homeless, and the imprisoned, who are treated as social "waste." [...] To be unable to transcend [...] the horror [...] of such a world order is what hell means [...]. Without a glimpse of an elsewhere or otherwise, we’re living in hell. [...] [P]eople are rejecting prison as the ideal model of social order. [...] Embedded in this resistance, sometimes explicitly and sometimes implicitly, is both a deep longing for and the articulation of, the existence of a life lived otherwise and elsewhere than in hell. [...] [W]hat’s in the shadow of the bottom line [...] -- what stands, living and breathing, in the place blinded from view. [...] Instincts and impulses are always contained by a system which dominates us so thoroughly that it decides when we can “have an impact” on “restructuring the world,” which is always relegated to the future. [...] “Self-determination begins at home [...].” Cultivating an instinctual basis for freedom is about identifying the longings that already exist -- however muted or marginal [...]. The utopian is not only or merely a “fantasy of” and for “the future collectivity”. It is not simply fantasmatic or otherworldly in the conventional temporal sense. The utopian is a way of conceiving and living in the here and now, which is inevitably entangled with all kinds of deformations [...]. But there are no guarantees. No guarantees that the time is right [...]; no guarantees that just a little more misery and suffering will bring the whole mess down; no guarantees that the people we expect to lead us will (no special privileged historical agents); [...] no guarantees that we can protect future generations [...] if we just wait long enough or plan it all out ahead of time; no guarantees that on the other side of the big change, some new utterly-unfathomable-but-worth-waiting-for happiness will be ours [...]. There are no guarantees of coming millenniums or historically inevitable socialisms or abstract principles, only our complicated selves together and a [...] principle in which the history and presence of the instinct for freedom, however fugitive or extreme, is the evidence of the [...] possibility because we’ve already begun to realize it. Begun to realize it in those scandalous moments when the present wavers [...]. The point is to expose the illusion of supremacy and unassailability dominating institutions and groups routinely generate to mask their fragility and their contingency. The point is [...] to encourage [...] us [...] to be a little less frightened of and more enthusiastic about our most scandalous utopian desires and actions [...], a particular kind of courage and a few magic tricks.

[Source: Avery Gordon. “Some thoughts on the Utopian.” 2016.]

135 notes

·

View notes

Text

What Went Wrong (and Right) with Conservative Philanthropy – Law & Liberty

To those who know the history of American conservatism, it is a familiar and oft-told story. Oversimplifying: From a relatively small base up until then, Arizona Senator Barry Goldwater’s traumatic loss in the 1964 presidential election birthed an ideologically driven conservative “counter-establishment” of journals and magazines, academic centers, and think tanks that took shape slowly, and then grew to the point at which it could help intellectually anchor, and make effective arguments for, the rise of Ronald Reagan, after which it helped implement his proposals.

Conservative philanthropic giving played a vital role in the initial creation and the growth of this counter-establishment. The individuals and institutions who underwrote the conservative movement were able to balance the formulation of ideas and the application of them, yielding policies that were geared toward results over the long term. Liberals generally do not contest this story, and they sometimes even honestly laud the effectiveness of the givers who were a key part of it.

Donald Trump’s dramatic victory in Election 2016 was traumatic, too—to liberals, who assumed their candidate would win, but also to what had become an actual, outright conservative establishment of its own. Trump was neither a product nor a beneficiary of the latter. For the most part, and for many reasons, nonprofit giving on the Right basically “missed” Trump and that which gave rise to him.

Not only did politically-minded conservative givers largely support other candidates in the Republican primaries, but policy-oriented and ideas-driven conservative givers didn’t seem to grasp the underlying causes for his overtaking those candidates. If the presidency was a victory that conservative givers were looking to help inform and assist, they failed.

Something was off-balance.

The Goldwater and Trump milestones were dramatic (and traumatic) for conservatism but in opposite ways. With some exceptions, conservative givers cannot plausibly claim much credit for policy victories achieved by Trump either now or for the rest of his tenure, which might extend to 2024. In fact, Trump would probably have been helped very much, before his victory and now, by a better giving balance between the three basics: ideas, policy, and patience. Conservatism, too, would have benefited from a better balance between these. However defined or redefined, conservatism would likely have been more securely anchored in lasting ideas, its policies probably better vetted and more likely to be instituted and implemented, over a longer term.

After Goldwater’s loss, there were years’ worth of ideas-driven building of institutions—then ultimate success, including electorally. There was not the same type or length of building before Trump’s electoral success. A rebalanced giving may still yield benefits in the future, so it is well worth considering how to go about achieving this.

Initially, Ideas

First, a backward look is necessary. Let us turn for guidance to James Piereson—a noted political theorist and the author of 2007’s Camelot and the Cultural Revolution, Piereson was the last executive director of the John M. Olin Foundation which, by design, depleted its assets in 2005. As he has recounted, after the end of the Second World War, “despite critics who viewed the concept of conservative ideas as a contradiction in terms,” many conservative philanthropists, “including the classical liberals in this camp, looked at books and ideas for guidance to a surprising degree.”[1]

This postwar period was the “classical era of conservative philanthropy,” in the words of Johns Hopkins political theorist Steven Teles. Both Piereson and Teles (at an important colloquium seven years ago at the Hudson Institute’s Bradley Center for Philanthropy and Civic Renewal) cited the guidance provided to conservative grantmakers by the thought of F.A. Hayek, most notably the Austrian economist’s 1944 book The Road to Serfdom. Conservatives took to heart Hayek’s warning about the danger of tyranny resulting from governmental central planning. As Piereson notes: “modern conservatives and classical liberals have generally been able to work toward a common goal of limiting the reach the state and the intrusion of politics into the life of civil society.”

In general, Hayek strongly emphasized the importance of ideas as the undergirding base of any successful political movement. An example that Hayek knew well: socialism. “In every country that has moved toward socialism,” said Hayek in a 1949 essay, “the phase of the development in which socialism becomes a determining influence on politics has been preceded for many years by a period during which socialist ideals governed the thinking of the more active intellectuals.”

Teles points to three philanthropies as typifying this “classical era,” and significantly, none was in Washington, D.C., or even on the East Coast. They were the William Volker Fund in Kansas City, Missouri, the Earhart Foundation in Ann Arbor, Michigan, and Pierre F. Goodrich’s brainchild, the Liberty Fund of Indianapolis, patron and publisher of the web site you are now reading.

Their Hayekian giving clearly and purposely balanced ideas with patience. These ideas were immanent.

Teles brought to light a 1956 internal Volker Fund document, blandly entitled Review and Recommendations, describing its grantmaking—which, as is the case for all private foundations, went to organizations that were classified under the Internal Revenue Code’s §501(c)(3) as being created for “charitable purposes,” including the education of policymakers and the public.

The Volker Fund’s list of principles included:

Risk-taking that involves disappointments;

Patience on the order of generations for ideas to germinate;

Actively seeking out people and ideas to support as opposed to waiting for requests to come in “over the transom”; and

The placement of ideas and values over mere metrics, mechanics, and techniques in grant consideration.

Adding Policy

The 1960s saw a cultural and political assault on many things, among them conservative ideas and conservatism—as evidenced in the lopsided, 44-states-to-six, 61.1 percent to 38.5 percent electoral result of November 3, 1964 in favor of President Lyndon Johnson. The liberally energetic Great Society that followed, and its aftermath, stirred action on the part of discontented conservative givers. Not a few were formerly liberal intellectuals who had grown weary of liberalism’s overreach and the damage it had wrought.

Conservative givers now mixed with many a “neoconservative” thinker and writer, their work in a tradition linked to Edmund Burke. The intellectual energy among these distinct intellectual tendencies was deemed worthy of substantial support.

According to Piereson:

The neoconservatives came from the left, accepted the New Deal, not necessarily the Great Society, dismissed the argument for free enterprise and placed great weight on cultural arguments in defense of the family, religion, and the institutions of civil society. . . . Few were academics. None that I know was an economist. They were essayists and editors used to making arguments about politics and culture, and in contrast to the Hayekians, they wanted to address immediate controversies. Far more than the classical liberals, they were interested in foreign policy, religion, and culture.

To some of them, the immanent religious ideas were transcendent.

Givers associated with this later era of conservative philanthropy (its “modern era,” as Teles labeled it during the 2012 discussion) include the now-defunct Olin Foundation in New York City, the Smith Richardson Foundation in Westport, Connecticut, and two not on the East Coast: the Scaife Foundations in Pittsburgh, and the Lynde and Harry Bradley Foundation in Milwaukee. One of the prime influencers of this group of institutions was the writer and editor Irving Kristol, considered the “godfather of neoconservatism.” Their Kristolian giving consciously balanced the three basics to which we referred: ideas, policy, and patience.

According to William A. Schambra, our former colleague at the Bradley Foundation, at Kristol’s urging, Olin, Scaife, and Bradley all underwrote studies that were “aimed at recovering the political philosophy of the American Founding, as expressed most authoritatively in the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution.” These studies were undertaken at the University of Chicago, Harvard, Claremont McKenna College, and other campuses, and at think tanks like AEI, the Heritage Foundation, and the Hoover Institution.

This burst of activity marked a revival of “otherwise obscure and seemingly antiquated political philosophers . . . that American progressivism had long since dismissed as so 18th century—so hopelessly out of step with the needs of modern society,” said Schambra. He made these observations at an underappreciated 2006 seminar held at Duke University, where he went on to say:

If conservative foundations did one thing during the rise of modern conservatism that was not likely to have been done by anyone else—that was, in other words, its unique and indispensable contribution—it was precisely funding the scholars, university centers, and policy institutes aimed at recapturing the Founders’ understanding of America, which would then animate and unite conservatism’s specific political, social, and economic programs.[2]

The roster of ideas and proposals came to include: supply-side economics and across-the-board tax cuts, “law and economics” and deregulation, aggressive foreign policy and national security stances through the whole of the Cold War and afterwards, “broken-windows” policing, work-based welfare reform, school choice in the form of vouchers and later charter schools, and a place for faith in the “public square.”

There were policy defeats, to be sure. Americans do not have individualized retirement accounts, higher education has not been reformed, and Obamacare was put in place. In and for the long term, however, conservative philanthropy ultimately helped yield some substantial policy achievements beginning when Ronald Reagan was elected in 1980, more than a quarter of a century after Goldwater’s loss. Among them: an expanding economy and bull market, victory in the first Gulf War, the fall of the Soviet Union, welfare reform, and expanded school choice.

External Envy

Conservatives have well-chronicled the philanthropic role in conservatism’s successes. John J. Miller’s 2003 Philanthropy Roundtable monograph Strategic Investment in Ideas: How Two Foundations Changed America is especially good, as is Miller’s 2005 book A Gift of Freedom: How the John M. Olin Foundation Changed America.

The success was so marked that liberals accepted the premises of conservative effectiveness—usually while enviously urging its replication by the foundations on the Left. In No Mercy: How Conservative Think Tanks and Foundations Changed America’s Social Agenda (1996), for example, Jean Stefancic and Richard Delgado of the University of Colorado Law School write: “We could not help being impressed with the professionalism and cold precision with which the right has been waging and winning struggle after struggle. . . . The dedication, economy of effort, and sheer ingenuity of much of the conservative machine are extraordinary.”

For another example, in the influential National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy’s Moving a Public Policy Agenda: The Strategic Philanthropy of Conservative Foundations (1997), Sally Covington thoroughly examined the grantmaking of 12 conservative philanthropies: Earhart, Olin, the Sarah Scaife and related Carthage Foundations, Smith Richardson, and Bradley, along with the Charles G. Koch and David H. Koch Charitable Foundations, the related Claude R. Lambe Charitable Foundation, the Philip M. McKenna Foundation, the JM Foundation, and the Henry Salvatori Foundation. There was also a 1996 report from Norman Lear’s People for the American Way, the invidiously titled Buying a Movement: Right-Wing Foundations and American Politics, which included the Adolph Coors Foundation in its study. Inside Philanthropy, moreover, noted that the Searle Freedom Trust should be included among effective conservative foundations.

“Although this effort has often been described as a ‘war of ideas,’ it has involved far more than scholarly debate within the halls of academe,” Covington writes. “Since the 1960s, conservative forces have shaped public consciousness and influenced elite opinion, recruited and trained new leaders, mobilized core constituencies, and applied significant rightward pressure on mainstream institutions, such as Congress, state legislatures, colleges and universities, the federal judiciary and philanthropy itself.”

In a 1998 American Prospect article about the “Lessons of Right-Wing Philanthropy”, Karen Paget, at the time a fellow of the Open Society Institute supported by George Soros, lamented that “the conservative infrastructure has far outstripped the left’s organizational capacity and resources. … The left has recently lost repeated battles to this conservative coalition over major initiatives such as affirmative action, welfare, immigration, English-only programs, and school vouchers.”

These self-critiques on the Left helped pave the way for the establishment, in 2003, of the liberal Center for American Progress think tank in Washington, and also the creation of the Democracy Alliance group of active liberal donors in 2005. Covington’s report in particular, said the Democracy Alliance’s president, Gara LaMarche, “crystallized for a lot of progressives the idea that the conservative foundations were kind of eating their lunch and then they were setting the terms of the debate in a way that the progressive foundations were not doing.”

“So looking to Olin and looking to Bradley, there was a challenge that was really laid down,” said LaMarche. He expressed admiration for “a very strategic use of money” by conservatives even though he disagreed with the ends of conservative philanthropy.

Internally, Another Explanation

Just as the Volker Fund internally catalogued what it believed were the characteristics of successful grantmaking in its 1956 review, Bradley program staff in Milwaukee made a similar effort in an internal 1999 document bearing the rather provocative title, The Bradley Foundation and the Art of (Intellectual) War. The two descriptions are quite consistent with each other.

According to Bradley’s Sun Tzu piece, there are four stages of policy initiatives: initiation, development, implementation, and consolidation. These yield 10 “rules of thumb” for good grantmaking:

Think of public policy making as a morality play, not an academic debate;

Be patient;

Do each step in order;

There are no shortcuts;

The best projects are found, not created;

Be prepared for unorthodox allies;

Measurement of results is tricky;

Try it “at home” first;

Learning curves should become shorter; and

Change should become incrementally cumulative, unpredictable, and self-generating.

Following these steps enabled ideas, policy, and patience to be balanced, in large part to good effect.

Worries and Warnings

In 2005, near the end of an article he wrote for Commentary magazine, “Investing in Conservative Ideas,” Piereson noted an important development: that the institutional emphasis on ideas was “giving way to a greater focus on politics and the nuts and bolts of policy.” As Schambra had observed at the above-mentioned Duke seminar, “Resurrecting an understanding of the American constitutional order that had been airbrushed from history by a century of scholarship would be no quick or easy task.” It wasn’t, and a certain impatience had set in among grantmakers on the Right.

This led many of them, in fact, to begin emulating grantmakers on the Left. According to Teles, “Metrics, measurement, logic models and the rest of the apparatus of new philanthropy [were] becoming as popular among the conservative philanthropists who go to Philanthropy Roundtable meetings as they [were] to mainstream and liberal foundations.”

Content was yielding to functionalism. Crudely, ends were yielding to means, with major consequences for the organizations. The growing demand for numericized proof of progress was something that neither Hayek nor Kristol would have thought prudent. In fact, they would probably have thought reliance on metrics to betray a lack of faith in the truth of conservatism’s core content, its underlying ideas.

Presentism and Politics

The new way included shorter time horizons by which to measure grantmaking success. The ends of short terms are always imminent, of course. They are seldom conducive to long-lasting results.

At times, the shorter-term thinking risked becoming so short as to correspond with certain officeholding terms. That is to say, private foundations had become more mindful than before of the political calendar, and those givers in a position to do so began to weigh supporting §501(c)(3) charitable-purpose organizations against organizations classified under §501(c)(4). The latter is for entities promoting “social welfare,” and this classification permits givers to engage in partisan political campaign activity and lobbying, so long as it is not their “primary” purpose or activity.

Conservative philanthropy was becoming more explicitly political, and as it did so, it became aligned with one political party. This yielded some successes, including the rise of the Tea Party and many state-level reforms, including meaningful labor-policy ones.

Yet it would not be accurate to conclude that this altered balance caused the surprising results of November 8, 2016—30 states and 304 electoral votes for the Republican Trump, as against 20 states and 227 electoral votes for the Democrat Hillary Clinton. By the same token, if results matter, one must note that the altered giving balance was consonant with those important results. In hindsight, one wonders whether a different balance might have been preferable for the conservative ideas supposedly being furthered by the giving.

For clearly the Republican candidate rejected many of the ideas espoused by the intellectual infrastructure of the Right and, for the most part, stylistically rejected those very intellectuals and their institutions. Representatively, almost all of the contributors to the attention-getting “Against Trump” symposium that National Review published in January 2016 had some affiliation with one or more conservative (c)(3) nonprofit groups.

Trump’s successful performance cannot be considered a product of conservative political spending, including in the nonprofit sphere. (He got almost all of his media for free.) Other contenders in the Republican primaries benefited much more from support from conservatives, as did Clinton benefit more from liberal political spending in the general election.

There have been good and serious outcomes for conservatives during the last two years, including an economy growing at nearly four percent per year, tax and regulatory reform, a positive peopling of the federal judiciary, the retaking of virtually all territory held by ISIS, and an overdue buildup of the U.S. military. Moreover, some (but by no means all) conservatives would count criminal justice reform as a success. There have been big defeats, too; debt and deficits, if they count, and Obamacare’s survival among them.

Rebalancing and Reordering

Goldwater lost, badly. Trump won, barely—in large part by dismissing or at least questioning conservatism as it had been understood, and supported, by conservative philanthropists. His victory should cause givers on the Right to continue critically questioning themselves. They should also consider how to go about best effectuating their or their donor’s intent.

Even if only as a perhaps-helpful intellectual exercise, they should ask whether it might have been better had Henry Olsen’s The Working-Class Republican: Ronald Reagan and the Return of Blue-Collar Conservatism (2017) or Patrick J. Deneen’s Why Liberalism Failed (2018) appeared before Election 2016. Or if Yoram Hazony’s The Virtue of Nationalism (2018) or Oren Cass’s The Once and Future Worker: A Vision for the Renewal of Work in America (2018) had appeared before Election 2016. Or for that matter, if a version of Victor Davis Hanson’s new The Case for Trump had done so. Or if the American Affairs journal, founded in 2017, had preceded the current administration.

Why, one might ask, did they all come after?

An easy answer is that Trump’s victory at the polls heightened intellectual energy on the Right—the same effect that was seen after Goldwater’s defeat at the polls. “This time it is not centralized in a few journals, institutes, and godfathers,” wrote Christopher DeMuth in an astute essay in the Claremont Review of Books. DeMuth cited some of the above-mentioned works, adding:

Rather—reflecting the spread of wealth and education and improvements in communications …—it is distributed and reticulated. Dozens of new and old journals, websites, and think tanks, plus innovations such as long-form podcasts and celebrity recirculation platforms, are variously devoted to politics, policy, law, economics, society, culture, philosophy, and security and foreign policy. The digitized, networked competition of ideas has generated new conservative and libertarian divisions and alliances, a parade of impressive new talents, and the appearance almost daily of substantial books and essays and vigorous rebuttals and surrebuttals to what was published last week.

The energy is again worth supporting. For a better-anchored and longer-lasting conservatism in the future—however it ends up being defined or redefined in the coming years—conservative givers should wonder whether a rebalancing of ideas, policy, and patience on their part might be in order. They should summon the discipline to develop and hew to a clear-eyed, longer-term worldview.

And they should humbly allow the immanent to transcend the imminent, for as long as they can.

[1] James Piereson’s comments, and those of Steven Teles and Gara LaMarche, are from a 2012 event convened at the Hudson Institute’s Bradley Center for Philanthropy and Civic Renewal. The discussion allowed Piereson to update the thoughts on philanthropy laid out in his 2005 article in Commentary magazine, “Investing in Conservative Ideas,” which is reproduced as a chapter in his 2015 book, Shattered Consensus: The Rise and Decline of America’s Postwar Political Order. He is now president of the William E. Simon Foundation and a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute.

[2] Presentation by William A. Schambra, “How Effective is Conservative Philanthropy?,” Terry Sanford Institute of Public Affairs, Duke University, December 6, 2006.

!function(f,b,e,v,n,t,s)if(f.fbq)return;n=f.fbq=function()n.callMethod? n.callMethod.apply(n,arguments):n.queue.push(arguments);if(!f._fbq)f._fbq=n; n.push=n;n.loaded=!0;n.version='2.0';n.queue=[];t=b.createElement(e);t.async=!0; t.src=v;s=b.getElementsByTagName(e)[0];s.parentNode.insertBefore(t,s)(window, document,'script','https://connect.facebook.net/en_US/fbevents.js'); (function(d, s, id) var js, fjs = d.getElementsByTagName(s)[0]; if (d.getElementById(id)) return; js = d.createElement(s); js.id = id; js.src = "http://connect.facebook.net/en_US/sdk.js#xfbml=1&version=v2.5"; fjs.parentNode.insertBefore(js, fjs); (document, "script", "facebook-jssdk"));

The post What Went Wrong (and Right) with Conservative Philanthropy – Law & Liberty appeared first on NEWS - EVENTS - LEGAL.

source https://dangkynhanhieusanpham.com/what-went-wrong-and-right-with-conservative-philanthropy-law-liberty/

0 notes

Text

Victimhood has become the ultimate status symbol

In recent years, campus activists have become an increasingly visible aspect of American life. In 2015, Yale professors Nicholas and Erika Christakis came under fire for encouraging students to critically consider a new policy on Halloween costumes. The controversy reached a boiling point when Nicholas Christakis met student demonstrators in a courtyard and attempted to engage them in discussion:

youtube

More recently, American Enterprise Institute scholar Charles Murray and Middlebury College Professor Allison Stanger were assaulted shortly after they were driven out of a lecture hall where Murray was scheduled to speak. The protesters succeeded in shutting down the talk by simply speaking over him:

youtube

This behavior is condemnable for a host of reasons, the least of which is that much of what the protesters are shouting is just factually incorrect (for example, Murray has long supported gay marriage, but the chant “racist, sexist, anti-gay” is simply too good to pass up). That the protesters eventually resorted to violence speaks to their moral certitude (a phenomenon that can be observed in other, similar protests), which is all the more troubling.

And yet, there are seemingly respectable people willing to defend this kind of savagery. Writing for Slate, Osita Nwanevu argued that the protesters were correct (and presumably, the violence that they employed was acceptable) because Trump: “In the Trump era, should we side with those who insist that the bigoted must traipse unhindered through our halls of learning? Or should we dare to disagree?” At Inside Higher Education, John Patrick Leary quipped that the protesters had “every right to shout him down.”

Disagreement is one thing. But shouting down opponents or – worse – engaging in violence in an effort to silence them is something else.

Cultural Evolution: From Honor to Dignity

In a country that has traditionally touted its tolerance for the expression of a diverse range of views, how did we get here? Let’s take a moment to review American cultural evolution.

Anyone who thinks that the nasty tone of American politics today is a historical anomaly should take a brief stroll down Google Lane and read about the Hamilton-Burr duel. The short version goes like this: Alexander Hamilton (former Secretary of Treasury) and Aaron Burr (Vice President of the United States) are longstanding political rivals. Upon learning that Hamilton had made particularly bruising comments about him at an elite New York dinner party, Burr challenges Hamilton to a duel. On July 11th, 1804, Burr shot Hamilton, who died the following day.

This sordid moment in American history is a classic example of what social scientists call a “culture of honor” – that is, a culture in which one’s reputation is made and maintained by a protective attitude and aggression toward those who would attempt to exert their dominance. Reputation – what others think of you – is paramount.

Such cultures are blessedly rare in the Western world, having been largely supplanted by what sociologist Peter Berger called “dignity culture.” In dignity cultures, a person’s worth is internal, and isolated from public opinion. What matters most is how one handles the minor slings and arrows that accompany many human interactions; a person with dignity does so quietly, usually by addressing the offending party directly and in private, if at all.

Dignity cultures are necessarily individualistic. There is no widespread notion of common guilt. Human agency is, by implication, paramount. It should be no surprise that for most of the 20th Century, Western societies have evolved to prize dignity over honor.

Let me be clear: this is a good thing. Most of us would recoil in horror at the thought of Mike Pence killing Jack Lew in a duel. I do not consider this point to be controversial. Some cultures are better than others, and Western culture today is certainly morally superior to its earlier instantiations, where slavery, sexism, and segregation were the norm. A culture in which dignity rather than honor is the standard bearer should be regarded as an appreciable improvement.

Victimhood Culture

But for many young Americans (and yes, this does appear to be a uniquely American phenomenon), the notion of quietly bearing one’s trials has become passe. Getting back to the issue at hand: I believe that much of what we have witnessed on college campuses in recent years can be explained by the rise of what sociologists Bradley Campbell and Jason Manning call “victimhood culture.” They state:

A culture of victimhood is one characterized by concern with status and sensitivity to slight combined with a heavy reliance on third parties. People are intolerant of insults, even if unintentional, and react by bringing them to the attention of authorities or to the public at large. Domination is the main form of deviance, and victimization a way of attracting sympathy, so rather than emphasize either their strength or inner worth, the aggrieved emphasize their oppression and social marginalization.

Watch the videos again: these students are engaging in precisely the behavior Campbell and Manning describe. They are demanding recognition of various victimhood statuses, and are unwilling to engage in any form of dialogue with those with whom they disagree. The category of “victim” is a moral absolute: no one can argue in favor of its fallibility.

But our understanding of victimhood culture and its relationship with the campus culture wars is incomplete without a commensurate recognition of what Nick Haslam calls concept creep: our understanding of what constitutes harm has broadened to include unintentional verbal slights, rather than being limited to overt, deliberate physical aggression.

This can be seen throughout the footage in question, but is particularly visible at one point in the Yale/Christakis row, when complaints take a turn for the hyperbolic: in response to an attempt by Christakis to appeal to the common humanity of everyone present, one student replies that such appeals are inappropriate “because we’re dying!”

It is difficult to understand how a student at one of the world’s top universities – well positioned to enter the halls of power after graduation – could reasonably be considered a member of an oppressed group, much less one that is being exterminated. Students at Yale, regardless of race or ethnicity, are among the cognitive and social elite. The idea that a simple e-mail about Halloween costumes could constitute an existential threat is nothing short of delusional.

But this observation is unlikely to quell the kind of uprising seen at Yale and Middlebury. As Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt point out, the students in these instances are likely engaging in a kind of emotional reasoning: making inferences about the state of the world based on their feelings, rather than an attempt to evaluate matters from a disinterested position that prizes objectivity.

Whither the Culture Of Victimhood

Advancing victimhood as a meritorious state while simultaneously expanding the criteria by which it is established means that those seeking social status are in constant competition. This “oppression olympics” (as some have termed it) means that marginalized status will become defined in an increasingly divisive manner. In this way, victimhood culture sows the seeds of its own destruction.

In an ironic twist, a culture of victimhood resembles a culture of honor in a surprising number of ways: for example, both demand that grievances be addressed, often publicly. It could even be argued that victimhood has obtained a privileged position that is impossible to challenge without incurring significant social costs. A new set of norms have emerged on college campuses, where there is a perverse honor in claiming to be oppressed.

Indeed, it is no wonder that victimhood culture has risen to prominence on elite colleges in one of the wealthiest nations in the world. Only under such relatively comfortable conditions could this kind of silliness prosper.

In fact, any worldview that prizes victimhood cannot survive outside the cloistered environment of a college campus. The real world – with its job markets, mortgage payments, and adult responsibilities – has a way of encouraging us to prize dignity over victimhood. Capitalism insists on results, and is relatively unconcerned with our subjective emotional evaluations of the world.

This is the primary reason why we ought not take the protesters at Yale and Middlebury too seriously. They will be forced to grapple with the real world and leave their activism behind.

Republished from Learn Liberty.

Sean Rife

Sean is an Assistant Professor of Psychology at Murray State University.

This article was originally published on FEE.org. Read the original article.

#censorship#Free Speech#higher education#liberal intolerance#Censorship#College#First Amendment#Video

0 notes

Text

Victimhood has become the ultimate status symbol

In recent years, campus activists have become an increasingly visible aspect of American life. In 2015, Yale professors Nicholas and Erika Christakis came under fire for encouraging students to critically consider a new policy on Halloween costumes. The controversy reached a boiling point when Nicholas Christakis met student demonstrators in a courtyard and attempted to engage them in discussion:

youtube

More recently, American Enterprise Institute scholar Charles Murray and Middlebury College Professor Allison Stanger were assaulted shortly after they were driven out of a lecture hall where Murray was scheduled to speak. The protesters succeeded in shutting down the talk by simply speaking over him:

youtube

This behavior is condemnable for a host of reasons, the least of which is that much of what the protesters are shouting is just factually incorrect (for example, Murray has long supported gay marriage, but the chant “racist, sexist, anti-gay” is simply too good to pass up). That the protesters eventually resorted to violence speaks to their moral certitude (a phenomenon that can be observed in other, similar protests), which is all the more troubling.

And yet, there are seemingly respectable people willing to defend this kind of savagery. Writing for Slate, Osita Nwanevu argued that the protesters were correct (and presumably, the violence that they employed was acceptable) because Trump: “In the Trump era, should we side with those who insist that the bigoted must traipse unhindered through our halls of learning? Or should we dare to disagree?” At Inside Higher Education, John Patrick Leary quipped that the protesters had “every right to shout him down.”

Disagreement is one thing. But shouting down opponents or – worse – engaging in violence in an effort to silence them is something else.

Cultural Evolution: From Honor to Dignity

In a country that has traditionally touted its tolerance for the expression of a diverse range of views, how did we get here? Let’s take a moment to review American cultural evolution.

Anyone who thinks that the nasty tone of American politics today is a historical anomaly should take a brief stroll down Google Lane and read about the Hamilton-Burr duel. The short version goes like this: Alexander Hamilton (former Secretary of Treasury) and Aaron Burr (Vice President of the United States) are longstanding political rivals. Upon learning that Hamilton had made particularly bruising comments about him at an elite New York dinner party, Burr challenges Hamilton to a duel. On July 11th, 1804, Burr shot Hamilton, who died the following day.

This sordid moment in American history is a classic example of what social scientists call a “culture of honor” – that is, a culture in which one’s reputation is made and maintained by a protective attitude and aggression toward those who would attempt to exert their dominance. Reputation – what others think of you – is paramount.

Such cultures are blessedly rare in the Western world, having been largely supplanted by what sociologist Peter Berger called “dignity culture.” In dignity cultures, a person’s worth is internal, and isolated from public opinion. What matters most is how one handles the minor slings and arrows that accompany many human interactions; a person with dignity does so quietly, usually by addressing the offending party directly and in private, if at all.

Dignity cultures are necessarily individualistic. There is no widespread notion of common guilt. Human agency is, by implication, paramount. It should be no surprise that for most of the 20th Century, Western societies have evolved to prize dignity over honor.

Let me be clear: this is a good thing. Most of us would recoil in horror at the thought of Mike Pence killing Jack Lew in a duel. I do not consider this point to be controversial. Some cultures are better than others, and Western culture today is certainly morally superior to its earlier instantiations, where slavery, sexism, and segregation were the norm. A culture in which dignity rather than honor is the standard bearer should be regarded as an appreciable improvement.

Victimhood Culture

But for many young Americans (and yes, this does appear to be a uniquely American phenomenon), the notion of quietly bearing one’s trials has become passe. Getting back to the issue at hand: I believe that much of what we have witnessed on college campuses in recent years can be explained by the rise of what sociologists Bradley Campbell and Jason Manning call “victimhood culture.” They state:

A culture of victimhood is one characterized by concern with status and sensitivity to slight combined with a heavy reliance on third parties. People are intolerant of insults, even if unintentional, and react by bringing them to the attention of authorities or to the public at large. Domination is the main form of deviance, and victimization a way of attracting sympathy, so rather than emphasize either their strength or inner worth, the aggrieved emphasize their oppression and social marginalization.

Watch the videos again: these students are engaging in precisely the behavior Campbell and Manning describe. They are demanding recognition of various victimhood statuses, and are unwilling to engage in any form of dialogue with those with whom they disagree. The category of “victim” is a moral absolute: no one can argue in favor of its fallibility.

But our understanding of victimhood culture and its relationship with the campus culture wars is incomplete without a commensurate recognition of what Nick Haslam calls concept creep: our understanding of what constitutes harm has broadened to include unintentional verbal slights, rather than being limited to overt, deliberate physical aggression.

This can be seen throughout the footage in question, but is particularly visible at one point in the Yale/Christakis row, when complaints take a turn for the hyperbolic: in response to an attempt by Christakis to appeal to the common humanity of everyone present, one student replies that such appeals are inappropriate “because we’re dying!”

It is difficult to understand how a student at one of the world’s top universities – well positioned to enter the halls of power after graduation – could reasonably be considered a member of an oppressed group, much less one that is being exterminated. Students at Yale, regardless of race or ethnicity, are among the cognitive and social elite. The idea that a simple e-mail about Halloween costumes could constitute an existential threat is nothing short of delusional.

But this observation is unlikely to quell the kind of uprising seen at Yale and Middlebury. As Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt point out, the students in these instances are likely engaging in a kind of emotional reasoning: making inferences about the state of the world based on their feelings, rather than an attempt to evaluate matters from a disinterested position that prizes objectivity.

Whither the Culture Of Victimhood

Advancing victimhood as a meritorious state while simultaneously expanding the criteria by which it is established means that those seeking social status are in constant competition. This “oppression olympics” (as some have termed it) means that marginalized status will become defined in an increasingly divisive manner. In this way, victimhood culture sows the seeds of its own destruction.

In an ironic twist, a culture of victimhood resembles a culture of honor in a surprising number of ways: for example, both demand that grievances be addressed, often publicly. It could even be argued that victimhood has obtained a privileged position that is impossible to challenge without incurring significant social costs. A new set of norms have emerged on college campuses, where there is a perverse honor in claiming to be oppressed.

Indeed, it is no wonder that victimhood culture has risen to prominence on elite colleges in one of the wealthiest nations in the world. Only under such relatively comfortable conditions could this kind of silliness prosper.

In fact, any worldview that prizes victimhood cannot survive outside the cloistered environment of a college campus. The real world – with its job markets, mortgage payments, and adult responsibilities – has a way of encouraging us to prize dignity over victimhood. Capitalism insists on results, and is relatively unconcerned with our subjective emotional evaluations of the world.

This is the primary reason why we ought not take the protesters at Yale and Middlebury too seriously. They will be forced to grapple with the real world and leave their activism behind.

Republished from Learn Liberty.

Sean Rife

Sean is an Assistant Professor of Psychology at Murray State University.

This article was originally published on FEE.org. Read the original article.

#censorship#Free Speech#higher education#liberal intolerance#Censorship#College#First Amendment#Video

0 notes

Text

Need to evaluate how universities produce knowledge today

THE Herald reported on NMMU vicechancellor Derrick Swartz’s address at Saturday’s firstyear students’ welcoming ceremony (“‘Fees cannot fall’ ”, January 23). Many had waited with great anticipation to hear his thoughts, given his absence during the eightweeklong shutdown last year.

Swartz’s address had quite a global outlook, with globalisation, and the rapid growth and displacement of industries by way of technological innovation taking up much of his speech.

As expected, his address also included views regarding the fees issue and related questions about protest. It was the usual constitutionalism he had also referred to in 2015 and a restatement of the university council’s position – that free education was a national government, not a university, issue.

As is the trend with much of the engagement regarding the fallist movement, Swartz’s address was limited only to questions of which actions were legal and which not, pronouncing he would clamp down on any attempts to blockade the university.

I ask whether his address offers sufficient contextualising of the wave of protests that have swept through the country’s universities over the past two years? I’ll borrow aspects of his address to answer this question making specific reference to the debate on decolonisation, one of the central issues for the fallist movement.

On the role of universities in society

It is important to consider that part of the fallist movement’s concerns have been the direction of the knowledge project in South Africa, because in its view very little of what is presented as South African scholarship reflects the South African experience. Much lacks a critique of racism, capitalism and colonialism’s role in the shaping of what is considered postapartheid South African society.

The dominant forms of knowledge that speak to modernity and the requirements of capitalism reinforces a violent system, and sanitises the structural exclusion of millions of people, their enslavement and land dispossession.

Swartz characterised universities as having the responsibility of generating what he termed “higher level knowledge”. Higher level knowledge, from what he presented, can be understood as knowledge that creates further opportunity for the expansion of the human enterprise on Earth.

It is often associated with the fields of science and technology, where new findings enable innovation in industry and provide opportunities for employment and through it for economic growth.

Such an understanding of what constitutes higher level knowledge fails to consider the political, social and cultural nature of knowledge production, and privileges a narrow view of education for economic ends alone. Thinking through the politics of knowledge requires that we probe what knowledge constitutes valid knowledge, for whom is such knowledge produced, by whom and for what purposes.

Swartz’s view, I believe, is extremely limiting and avoids any reference to the critically important debate which the present conflict in the university raises – about the content, form and purpose of high level knowledge production and its intellectual challenges.

In this regard even a cursory examination of the main characteristics of the global order will show that the great crisis of the world today is represented by deepening inequality, racism, violence against women, destruction of the natural environment and the growing impunity of warmongering corporate states. This warrants an urgent exploration of alternative knowledge for an alternative society.

This implies that our society, at a global and local level, operates around a particular form of knowledge – one which is racist, capitalist and patriarchal, and construes ideas of governance and power in specific ways that promotes the prevailing arrangement of society.

American scholar Ernst Boyer is often credited with the idea of scholarly engagement within higher education. Boyer fits several practices within scholarship into different categories, namely the scholarship of discovering knowledge, the scholarship of integrating knowledge to avoid pedantry, and the sharing of knowledge to avoid discontinuity.

He arrives at engagement, as the form of scholarship that is dedicated to application, addressing questions of active citizenship and immediate social challenges. The rise of engaged scholarship has been coupled with the rise of participatory research methodologies that recognise the importance of collectivist approaches to knowledge production that do not rest on the perspective of a distant researcher above that of the socalled objects of research.

Yet Boyer’s formulation of engaged scholarship is limited in its lack of critique of the idea of the university as a colonising, capitalist institution which organises knowledge in ways that support the domination of the world and culture by EuroAmerican capitalist modernity.

As a result, in keeping with the capitalist mandate that subdues research to safe questions that do not challenge authority and unsettle global capital, many institutions, like NMMU, do the bulk of their engagement work in the form of partnerships with industries – providing cuttingedge research to several sectors including mining, motor and chemical industries – with some charitybased models where very little of the interaction with “communities” feeds back knowledge into the university’s own knowledge construction processes, its curriculum and research in particular.

A recent example of why this is a problem is that there are disputes emerging around the Missionvale campus regarding the participation of community members in various projects on the campus, including a project involving food garden cooperatives.

It should be within the ambit of the university to work with communities to find sustainable ways of living and to be a critical voice in challenging how the world is organised against the poor. Very little of what is taught within university lecture halls is informed by any analysis of the knowledge that arises from engagements beyond the gates of the institutions.

A case for new knowledge

Higher level knowledge has to be knowledge that challenges our traditional ways (I refer mostly to modernity as tradition here) of thinking at all levels of society. It cannot only be limited to instrumentalist approaches to satisfy the needs of industry but must also, critically problematise the destructive nature of the present social system.

On the university and its meaning today

In a university that seeks to produce dynamic higher level knowledge, questions of globalisation should not be limited to discourse about the changing nature of work and industry in the last 30 to 50 years, regarded as naturally occurring phenomena. It should be seen as an outcome of deliberate human action.

The loss of jobs and industries are results of human decisionmaking and in particular profitmaking by global elites. It is intellectually disingenuous to present them as purported by Swartz in his address.

Also globalisation must be understood as a product of colonialism that has impacts for culture, reason and knowledge in society today.

In as much as it is important to possess a knowledge of technological tools that now make our society tick, it is also important that for questions of sustainability and social justice, universities must also produce graduates who understand the world beyond market driven knowledge.

Most importantly, an African university must offer an understanding of the world that is informed by the very experience of African people on the continent. Without such we will continue to promote a knowledge that doesn’t allow us to construct the alternative society we need.

It is thus important to interrogate the current wave of student protests at university much more deeply, especially with regard to their critique of the process of knowledge production.

Whatever disagreement may exist with the methods employed by students and workers, they have raised an important discourse which dares us to think deeper about the challenges that exist in our society, and about what and how change should occur if we are to establish a different society.

25 January 2017

#fallism#feesmustfall#rhodesmustfall#engaged scholarship#african education#education reform#sociology of knowledge#sociology of education

0 notes