#and how he's also shown sweating bullets throughout this whole issue

Photo

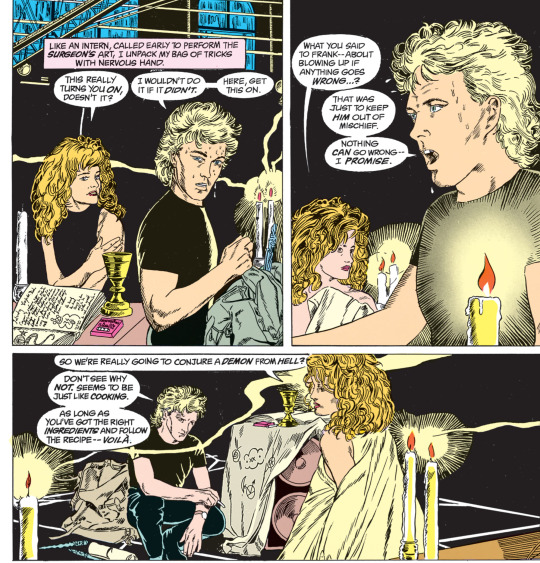

#;muse#ah the folly of youth#: )#remember guys#john says summoning demons is a lot like cooking#except without the damnation of a child and just about everyone else present there with him#all bc he misnamed nergal#: )))))#also love how top panel lowkey touches on just how much john was all bought into magic#and how he's also shown sweating bullets throughout this whole issue#chef kiss good origin story in spite of the lasting trauma

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

What Matters

Stone’s experiences fighting in the Vietnam War, a conflict in which he spent 360 days serving with distinction in the United States Army, have unsurprisingly formed a huge part of his outlook as a filmmaker. From his critique of American foreign policy in South America in Salvador, his condemnation of the American government’s treatment of veterans in Born On The Fourth Of July, and his portrayal of the true horrors of the Vietnam War in Platoon, Stone’s anti-establishment streak is clear to see. It’s something he has always worn with a badge of honor and made no attempts to water down. Bringing what he sees as the harsh realities of American foreign policy into the conscious of mainstream cinema audiences is a recurring theme throughout his work.

Platoon is understandably seen as Stone’s most personal work, given its direct link to his own tour of duty. However, I’d argue that JFK is a very close second. The assassination of John F. Kennedy was a pivotal moment in the life of the young director. According to Stone it marked the start of what he saw as a fall from grace for America and their embarking on a dark road that began with Kennedy’ successor Lyndon Johnson escalating the war in Vietnam. In the production notes for JFK Stone stated:

“Kennedy to me was like the Godfather of my generation. He was a very important figure, a leader, a prince in a sense. And his murder marked the end of a dream. The end of a concept of idealism I associated with my youth.”

These strong feelings flow right the way through the movie and it’s clearly a passion project which Stone made with an intense verve. However critics could arguably point out that it was this passion which blinded Stone to certain realities and led to him to take some fairly strong liberties with the truth. [...]

Treated purely as a piece of drama, JFK is a mesmerizing blend of styles and formats. It has elements of documentary, historical recreation, family drama, criminal investigation, political thriller, and courtroom drama coursing through it. At its center sits District Attorney Jim Garrison (Kevin Costner) and the story of how he and his team successfully brought about the first trial relating to the assassination of President Kennedy. The dramatic thrust of the movie is deliberately simple, underneath all the layers of intrigue, it’s a group of dedicated and tireless public servants seeking to uncover the truth and expose the shady goings on of those in power. It’s compelling and passionate cinema that whips you up and demands your attention.

From the very outset it’s easy to see why JFK won Academy Awards for both Cinematography and Editing. The opening montage which begins the movie is a bravura introduction that condenses down a wealth of crucial information into a very short space of time. We see historical archive footage of Kennedy’s speeches, his family life, his meetings with other politicians, as well as footage of other key players and events from the era.

As the footage begins, a key theme is immediately articulated via Dwight D. Eisenhower’s ominous warning against the rise to prominence of the military-industrial complex. We are then shown newsreels documenting Kennedy’s narrow election victory over Richard Nixon as the ground is set for his arrival in power.

The tempo then begins to pick up, the editing quickens and the tone becomes more serious, as the Cold War and its milieu unfolds. The Bay of Pigs fiasco, the annexation of Cuba, Kennedy’s deal with Krushchev and his apparent desire to withdraw from Vietnam are all explained in brief via archive footage and calming narration by none other than Martin Sheen. Key concepts and themes are now lodged in our minds. These include Kennedy’s willingness to work with Russia, his supposed weakness on Communism, and the threat he posted to those with a vested interest in war.

Suddenly, in amongst the newsreel footage comes our first fictional scene involving a call girl being ditched by the roadside. It marks a sudden shift that sees the montage’s pace and intensity increase once more. The music shifts from a brisk military drum roll to a far more menacing and tense piece. From here the momentum ramps up towards that fateful day in Dallas as footage of Kennedy’s arrival in the city is blended with recreations of his route to Dealey Plaza. Eventually it cuts to footage from the Zapruder film and as his car makes that final turn, we hear a gunshot ring out and it all fades to black.

Thanks to Stone and his editors Joe Hutshing and Pietro Scalia, the movie’s entire tone and raison d’etre is perfectly laid out before us. This whole sequence runs just shy of seven minutes. In those seven minutes a huge amount of information is relayed to us. You are thus launched into proceedings imbued with a sense of both historical context and atmosphere, as well as a range of questions already primed and ready to go.

Hutshing and Scalia utilized a range of sources for their visual jigsaw including newsreels, stock photos, home movies, and Stone’s own new footage. The blending of historical fact and fiction begins here, with real-life footage and dramatic re-creations mixed together through a series of quick cuts in order to develop Stone’s story. The issue with this perhaps being that it’s sometimes hard to tell when the archive footage ends and the new footage begins. This process of merging together fresh footage and archive pieces comes not only in the introduction, but several times throughout the movie.

When the mysterious 'X' (Donald Sutherland) lays out his version of events for Jim Garrison, we again witness an onslaught of visual information which seemingly backs up his claim. Likewise, when Garrison is in the courtroom laying out his own version of events, we again view it via a gripping montage of moments which reinforce his argument. In all three cases, the fast paced editing drives the story along and gives each sequence a sense of urgency and vitality.

The film’s cinematography is also a joy to watch and more than worthy of its Oscar win. Robert Richardson and Stone delivered a film that could go from brooding and sombre, to vibrant and urgent in the blink of an eye. Moments such as Garrison interviewing Clay Shaw (Tommy Lee Jones) on a rain-soaked Easter weekend or Garrison’s solitary viewing of Robert Kennedy’s shooting are shrouded in gloom and despondency, reflective of the sense of despair Stone himself felt over these moments. Meanwhile, the dizzying courtroom sequence delivers many little gems, from the camera stalking Garrison as he prowls the debate floor, to the way it cuts away to capture the shocked looks of the sweat-laden fan-holding courtroom audience. [...]

It’s seeing how the pieces fit together that makes the film so fascinating. Pieces which are hinted at in the opening montage, characters referenced in or even merely glimpsed in flashbacks, come back in to proceedings later on as the puzzle takes shape. For example, one of the 'Nazi-type' mercenaries shown early on in the background at one of David Ferrie’s (Joe Pesci) training camps, shows up later on as an apparent contact on the ground giving a signal to the 'hobos' on the day of the assassination. This man never utters a line, yet he offers a subtle through line linking earlier moments with the broader story.

While Stone himself deserves great credit for producing this huge piece of work, he was helped majorly by a brilliant all-star cast. To name but a few we saw Kevin Costner, Tommy Lee Jones, Gary Oldman, Joe Pesci, Kevin Bacon, Jack Lemmon, Donald Sutherland, Ed Asner, and Sissy Spacek all throwing themselves into their roles. Even John Candy and Walter Matthau, who both only have very brief cameos, are scintillating to watch. Candy’s perspiring jazz-talking dodgy attorney oozes screen presence, while Matthau’s good ol’ Senator is the cynical doubter who reignites Garrison’s interest in the assassination. [...]

From the Zapruder film onwards we sense Garrison is truly hitting his stride, his dismantling of the so called 'single bullet' theory is so erudite and persuasive you’ll almost want to just believe he is right and completely avoid the fairly important factors Stone failed to include. The fact that Garrison does not go on to win his case and the jury instead finds in favor of Shaw, is utterly immaterial. It’s the seeds of doubt he planted and the broader idea he put forward that matters. As he walks off with his family, head held high, what matters is that he tried.

-Robert Keeling, “Oliver Stone's JFK: A Masterful Blend of Fact and Fiction,” Den of Geek, Apr 19 2017 [x]

1 note

·

View note